Medellín Cartel

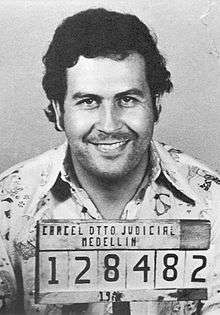

The Medellín Cartel (Spanish: Cartel de Medellín) was a powerful and highly organized Colombian drug cartel and terrorist-type criminal organization originating in the city of Medellín, Colombia that was founded and led by Pablo Escobar. The drug cartel operated from 1972 to 1993 in Bolivia, Colombia, Panama, Central America, Peru, and the United States, as well as in Canada. At the height of its operations, the Medellín Cartel smuggled multiple tons of cocaine each week into countries all over the world and brought in up to US$60 million daily in drug profits.[2][3] The organization, especially in its later years was known for its use of violence for political aims and its asymmetric war against the Colombian government, primarily in the form of bombings, kidnappings, indiscriminate murder of law enforcement and political assassination.[4][5]

| Founded by | Pablo Escobar |

|---|---|

| Founding location | Antioquia Department, Colombia |

| Years active | 1972–1993 |

| Territory | Colombia, México, New York, Florida |

| Ethnicity | Colombians and international people out of Colombia. |

| Criminal activities | Drug trafficking, arms trafficking, bombing, terrorism, bribery, kidnapping, extortion, money laundering, murder, racketeering |

| Allies | Guadalajara Cartel (defunct) Muerte a Secuestradores (defunct) La Corporación (defunct) Los Priscos (defunct) Gulf Cartel |

| Rivals | Cali Cartel (defunct) Los Pepes (defunct) Colombian government American government DEA CIA |

| Medellín Cartel |

|---|

|

History

In the late 1960s, illegal cocaine trade became a significant problem and became a major source of profit. Drug lord Pablo Escobar distributed cocaine for the Cartel in New York City and later Miami, establishing a crime network that at its height trafficked around 300 kilos per day.[6] By 1982, cocaine surpassed coffee as the chief Colombian export. Private armies were raised to fight off guerrillas who were trying to either redistribute their lands to local peasants, kidnap them, or extort the gramaje money Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia or FARC) attempted to steal.[7][8][9]

At the end of 1981 and the beginning of 1982, members of the Medellín Cartel, the Colombian military, the U.S.-based corporation Texas Petroleum, the Colombian legislature, small industrialists, and wealthy cattle ranchers came together in a series of meetings in Puerto Boyacá and formed a paramilitary organization known as Muerte a Secuestradores ("Death to Kidnappers", MAS) to defend their economic interests, and to provide protection for local elites from kidnappings and extortion.[10][11][12] By 1983, Colombian internal affairs had registered 240 political killings by MAS death squads, mostly community leaders, elected officials, and farmers.[13]

The following year, the Asociación Campesina de Ganaderos y Agricultores del Magdalena Medio ("Association of Middle Magdalena Ranchers and Farmers", ACDEGAM) was created to handle both the logistics and the public relations of the organization, and to provide a legal front for various paramilitary groups. ACDEGAM worked to promote anti-labor policies, and threatened anyone involved with organizing for labor or peasants' rights. The threats were backed up by the MAS, which would attack or assassinate anyone who was suspected of being a "subversive".[10][14] ACDEGAM also built schools whose stated purpose was the creation of a "patriotic and anti-Communist" educational environment, and built roads, bridges, and health clinics. Paramilitary recruiting, weapons storage, communications, propaganda, and medical services were all run out of ACDEGAM headquarters.[14] [15]

By the mid-1980s, ACDEGAM and MAS had undergone significant growth. In 1985, the drug trafficker Pablo Escobar began funneling large amounts of cash into the organization to pay for equipment, training, and weaponry. Money for social projects was cut off and redirected towards strengthening the MAS. Modern battle rifles, such as the AKM, FN FAL, Galil, and HK G3, were purchased from the military, INDUMIL, and drug-funded private sales. The organization had computers and ran a communications center that worked in coordination with the state telecommunications office. They had 30 pilots, and an assortment of fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters. British, Israeli, and U.S. military instructors were hired to teach at paramilitary training centers.[10][12][14][15][16][17]

Relations with the Colombian government

Once U.S. authorities were made aware of "questionable activities", the group was put under Federal Drug Task Force surveillance. Evidence was gathered, compiled, and presented to a grand jury, resulting in indictments, arrests, and prison sentences for those convicted in the United States. However, very few Colombian cartel leaders were actually taken into custody as a result of these operations. Mostly, non-Colombians conspiring with the cartel were the "fruits" of these indictments in the United States..

Most Colombians targeted, as well as those named in such indictments, lived and stayed in Colombia, or fled before indictments were unsealed. However, by 1993 most, if not all, cartel fugitives had been either imprisoned, or located and shot dead, by the Colombian National Police trained and assisted by specialized military units and the CIA.

The last of Escobar's lieutenants to be assassinated was Juan Diego Arcila Henao, who had been released from a Colombian prison in 2002 and hidden in Venezuela to avoid the vengeance of "Los Pepes". However he was shot and killed in his Jeep Cherokee as he exited the parking area of his home in Cumaná, Venezuela, in April 2007.[18]

While it is broadly believed that Los Pepes have been instrumental in the assassination of the cartel's members over the last 21 years, it is still in dispute whether the mantle is just a screen designed to deflect political repercussions from both the Colombian and United States governments' involvement in these assassinations.

Fear of extradition

Perhaps the greatest threat posed to the Medellín Cartel and the other traffickers was the implementation of an extradition treaty between the United States and Colombia. It allowed Colombia to extradite to the US any Colombian suspected of drug trafficking and to be tried there for their crimes. This was a major problem for the cartel, since the drug traffickers had little access to their local power and influence in the US, and a trial there would most likely lead to imprisonment. Among the staunch supporters of the extradition treaty were Colombian Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara (who was pushing for more action against the drug cartels), Police Officer Jaime Ramírez, and numerous Colombian Supreme Court judges.

However, the cartel applied a "bend or break" strategy towards several of these supporters, using bribery, extortion, or violence. Nevertheless, when police efforts began to cause major losses, some of the major drug lords themselves were temporarily pushed out of Colombia, forcing them into hiding from which they ordered cartel members to take out key supporters of the extradition treaty.

The cartel issued death threats to the Supreme Court Judges, asking them to denounce the Extradition Treaty. The warnings were ignored. This led Escobar and the group he called Los Extraditables ("The Extraditables") to start a violent campaign to pressure the Colombian government by committing a series of kidnappings, murders, and narco-terrorist actions.[19][20][21][22]

Alleged relation with the M-19

In November 1985, 35 heavily armed members of the M-19 guerrilla group stormed the Colombian Supreme Court in Bogotá, leading to the Palace of Justice siege. Some claimed at the time that the cartel's influence was behind the M-19's raid, because of its interest in intimidating the Supreme Court. Others state that the alleged cartel-guerrilla relationship was unlikely to occur at the time because the two organizations had been having several standoffs and confrontations, like the kidnappings by M-19 of drug lord Carlos Lehder and of Nieves Ochoa, the sister of Juan David Ochoa.[23][24][25][26] These kidnappings led to the creation of the MAS/Muerte a Secuestradores ("Death to Kidnappers") paramilitary group by Pablo Escobar. Former guerrilla members have also denied that the cartel had any part in this event.[27] The issue continues to be debated inside Colombia.[28][29][30][31]

Assassinations

As a means of intimidation, the cartel conducted thousands of assassinations throughout the country. Escobar and his associates made it clear that whoever stood against them would risk being killed along with their families. Some estimates put the total around 3,500 killed during the height of the cartel's activities, including over 500 police officers in Medellín, but the entire list is impossible to assemble, due to the limitation of the judiciary power in Colombia. The following is a brief list of the most notorious assassinations conducted by the cartel:

- Kyle Luis Moreno , two DAS agents who had arrested Pablo Escobar in 1976. Among the earliest assassinations of authority figures by the cartel.

- Rodrigo Lara, Minister of Justice, killed on a Bogotá highway on April 30, 1984, when two gunmen riding a motorcycle approached his vehicle in traffic and opened fire.[32]

- Tulio Manuel Castro Gil, Superior Judge, killed by motorcycle gunmen in July 1985, shortly after indicting Escobar.[33]

- Enrique Camarena, DEA agent, February 9, 1985, killed in Guadalajara, Mexico. Tortured and murdered on orders of members of the Guadalajara Cartel and Juan Matta-Ballesteros, a drug lord of the Medellin Cartel.

- Hernando Baquero Borda, Supreme Court Justice, killed by gunmen in Bogotá on July 31, 1986.[34]

- Jaime Ramírez, Police Colonel and head of the anti-narcotics unit of the National Police of Colombia. Killed on a Medellín highway in November 1986 when assassins in a red Renault pulled up beside his white Toyota minivan and opened fire. Ramírez was killed instantly; his wife and two sons were wounded.[35]

- Guillermo Cano Isaza, director of El Espectador, killed in December 1986 in Bogotá by gunmen riding a motorcycle.[36]

- Jaime Pardo Leal, presidential candidate and head of the Patriotic Union party, killed by a gunman in October 1987.[37]

- Carlos Mauro Hoyos, Attorney General, kidnapped then killed by gunmen in Medellín in January 1988.[38]

- Antonio Roldan Betancur, governor of Antioquia, killed by a car bomb in July 1989.[5]

- Waldemar Franklin Quintero, Commander of the Antioquia police, killed by gunmen in Medellín in August 1989.[39]

- Luis Carlos Galán, presidential candidate, killed by gunmen during a rally in Soacha in August 1989. The assassination was carried out on the same day the commander of the Antioquia police was gunned down by the cartel.[40]

- Carlos Ernesto Valencia, Superior Judge, killed by gunmen shortly after indicting Escobar on the death of Guillermo Cano, in August 1989.[41]

- Jorge Enrique Pulido, journalist, director of Jorge Enrique Pulido TV, killed by gunmen in Bogotá in November 1989.[42]

- Diana Turbay, journalist, chief editor of the Hoy por Hoy magazine, killed during a rescue attempt in January 1991.[43]

- Enrique Low Murtra, Minister of Justice, killed by gunmen in downtown Bogotá in May 1991.[4]

- Myriam Rocio Velez, Superior Judge, killed by gunmen shortly before she was to sentence Escobar on the assassination of Galán, in September 1992.[44][45]

Miguel Maza Márquez was targeted in the DAS Building Bombing, resulting in the death of 52 civilians caught in the blast. Miguel escaped unharmed.

In 1993, shortly before Escobar's death, the cartel lieutenants were also targeted by the vigilante group Los Pepes (or PEPES, People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar).

With the assassination of Juan Diego Arcila Henao in 2007, most if not all of Escobar's lieutenants who were not in prison had been killed by the Colombian National Police Search Bloc (trained and assisted by U.S. Delta Force and CIA operatives), or by the Los Pepes vigilantes.[46][47]

DEA agents considered that their four-pronged "Kingpin Strategy", specifically targeting senior cartel figures, was a major contributing factor to the collapse of the organization.[48]

Legacy

La Oficina de Envigado is believed to be a partial successor to the Medellín organization. It was founded by Don Berna as an enforcement wing for the Medellín Cartel. When Don Berna fell out with Escobar, La Oficina caused Escobar's rivals to oust Escobar. The organization then inherited the Medellín turf and its criminal connections in the US, Mexico, and the UK, and began to affiliate with the paramilitary United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, organizing drug trafficking operations on their behalf.[49]

In popular culture

The cartel is either featured or referenced in numerous works of popular culture.

- Blow: 2001 film about drug smuggler George Jung and the Medellín Cartel

- Narcos is a Netflix original television series (2015–2017) that chronicles the life of Pablo Escobar and the rise of the Medellín Cartel. The first and the second season depict his rise to the status of a powerful drug lord as well his narcoterrorist acts, war against the Colombian government and finally; his death. The role of Escobar is played by Brazilian actor Wagner Moura.

- Cocaine Cowboys and Cocaine Cowboys 2: documentary series about the Miami Drug War and Griselda Blanco

- American Desperado: a book by journalist Evan Wright and former Medellín Cartel trafficker Jon Roberts

- The Two Escobars: an ESPN 30 for 30 film details the link between the Medellín Cartel and the rise of Colombian football

- American Made: 2017 fictionalised film about drug smuggler Barry Seal and the Medellín Cartel

- Season 2 episode 7 of Deadliest Warrior pitted the Medellín Cartel against the Somali Pirates with Michael Corleone Blanco, Son Of Griselda Blanco and gangster turned informant Kenny "Kenji" Gallo testing the cartel's weapons.

See also

- Colombian Conflict

- Miami Drug War

- Juan Matta-Ballesteros

- Jon Roberts

- Max Mermelstein

- Mickey Munday

- Narcotrafficking in Colombia

- Drug barons of Colombia

- Norte del Valle Cartel

- Jack Carlton Reed

- Virginia Vallejo

References

- Peñaloza, General Carlos (2014). El Delfín de Fidel: La historia oculta tras el golpe del 4F. p. 195. ISBN 978-1505750331.

Arnaldo Ochoa knew that Fidel secretly exchanged weapons with the Medellin Cartel for money and drugs. And this turbulent partnership included the authorization for the landing of planes in Cuba and loaded with cocaine to be transferred then and speedboats to the US. Fidel had appealed to this source of income to compensate for the reduction of the Soviet subsidy. And illegal trade, Castro delivered Kalashnikov rifles, ammunition and other supplies brought as loot of war from Africa.

- Miller Llana, Sara (25 October 2010). "Medellín to keep the peace". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- UNODC (2009). "Cocaine" (PDF). World Drug Trade.

- David L. Marcus (May 2, 1991). "Colombia professor's slaying shows drug war far from over". The Dallas Morning News.

- "Colombian Governor Assassinated". The Philadelphia Inquirer. July 5, 1989. p. B20.

- Corben, Billy (director); Cosby, Charles (himself); Blanco, Griselda (herself) (July 29, 2008). Cocaine Cowboys 2: Hustlin' with the Godmother (DVD). Magnolia Home Entertainment. ASIN B00180R03Q. UPC 876964001366. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- Marc Chernick (March–April 1998). "The paramilitarization of the war in Colombia". NACLA Report on the Americas. 31 (5): 28. doi:10.1080/10714839.1998.11722772.

- Forrest Hylton (2006). Evil Hour in Colombia. Verso. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-1-84467-551-7.

- "II. History of the Military-Paramilitary Partnership". HRW. 1996.

- Richani, 2002: p.38

- Hristov (2009). Blood Capital. pp. 65–68. ISBN 9780896802674.

- Santina, Peter (Winter 1998–1999). "Army of terror". Harvard International Review. 21 (1).

- Geoff Simons (2004). Colombia: A Brutal History. Saqi Books. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-86356-758-2.

- Pearce, Jenny (May 1, 1990). 1st. ed. Colombia:Inside the Labyrinth. London: Latin America Bureau. p. 247. ISBN 0-906156-44-0

- "Who Is Israel's Yair Klein and What Was He Doing in Colombia and Sierra Leone?". Democracy Now!. June 1, 2000. Archived from the original on March 14, 2007.

- Harvey F. Kline (1999). State Building and Conflict Resolution in Colombia: 1986–1994. University of Alabama Press. pp. 73–74.

- El Tiempo, Bogotá Abril 18, 2007

- "Maruja Pachón, ex ministra de Educación". 23 May 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- "'News Of A Kidnapping' A Hit In Iran After Opposition Leader's Recommendation". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- "Filmarán la novela 'Noticia de un secuestro' de Gabriel García Márquez". eltiempo.com. 2008-10-03. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- "Gabriel Garca Mrquez – Noticia de un secuestro". Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- "News". El Mundo.

- "Murió Juan David Ochoa, uno de los fundadores del cartel de Medellín". eltiempo.com. 2013-07-25. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- "Marta Nieves Ochoa, hermana de Fabio Ochoa". 2007-10-18. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- "1981-Plagio de Martha Ochoa se creó el MAS". ElEspectador. 2008-07-12. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- "M-19 cambió drogas por armas". El País. 6 October 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2006.

- David McClintick (November 28, 1993). "Lost in the Ashes". The Washington Post. pp. 268, 279.

- "Un Grito por el Palacio". Cromos. November 25, 2005.

- "Palacio de Justicia, 20 años de dolor". El País. November 7, 2005.

- "M-19 cambió drogas por armas". El País. October 6, 2005.

- Lernoux, Penny (June 16, 1984). "The minister who had to die: Colombia's drug war". The Nation.

- "Thirty Years of America's Drug War: A Chronology". PBS.

- "High judge fighting drug traffic is slain in Colombia". Chicago Sun-Times. August 1, 1986. p. 32.

- "The Murderous Cartel: Taking the Life of a Top Cop". Wichita Eagle. December 20, 1987. p. 12A.

- Mark A. Uhlig (May 24, 1989). "As Colombian Terror Grows, The Press Becomes the Prey". The New York Times. p. Section A, Page 1, Column 5.

- "Colombians Strike: Violence Spreads Death Toll Rises After Killing of Leftist Political Leader". The Washington Post. October 14, 1987. p. Section A.

- Alan Riding (February 1, 1988). "Colombians Grow Weary of Waging the War on Drugs". The New York Times. p. Section A, Page 1, Column 4.

- "Gang Murders Cop Who Fought Medellin Cartel". Miami Herald. August 19, 1989. p. 1A.

- Douglas Farah (August 17, 1990). "Colombian: Israeli Aided Assassins Candidate's Slaying Launched Drug War". The Washington Post. pp. A SECTION.

- "Colombian Judge In Drug Case Killed". The Washington Post. August 18, 1989. p. A SECTION.

- "Soldiers Kill 8 Rebels". Wichita Eagle. November 9, 1989. p. 12A.

- Douglas Farah (September 21, 1990). "Drug Cartel Kidnaps 3 Colombian Notables". The Washington Post. pp. A SECTION.

- "3 Who Escaped With Colombia Drug Lord Give Up". The New York Times. October 9, 1992. p. Section A, Page 5, Column 1.

- "Judge murdered – World – News". The Independent. 1992-09-20. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- "Uppsala Conflict Data Program". Conflict Encyclopedia.

- "Colombia, non-state Conflict, Medellin Cartel – PEPES". Tiempo. Bogotá. 1993.

- Streatfeild, D. (October 2000). "Interview with DEA Agent #2". Source.

- Muse, Toby (April 10, 2012). "New drug gang wars blow Colombian city's revival apart". The Guardian. Medellín.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Medellín Cartel. |

- Bowden, Mark (2011). Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World's Greatest Outlaw. A book that details the efforts by the governments of the United States and Colombia, their respective military and intelligence forces, and Los Pepes (controlled by the Cali cartel) to stop illegal activities committed by Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar and his subordinates. It relates how Escobar was killed and his cartel dismantled.

- "United States vs. Robert Elisio Serry, Walter J Magri Jr Importation of Cocaine (Sarasota News Times)". Lawyer Luiz Felipe Mallmann de Magalhães 31. March 21, 1990.