Balearic Islands

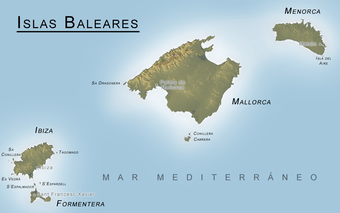

The Balearic Islands (/ˌbæliˈærɪk/ BAL-ee-ARR-ik, also US: /ˌbɑːl-/ BAHL-, UK: /bəˈlɪərɪk/ bə-LEER-ik;[1][2] Catalan: Illes Balears [ˈiʎəz bələˈas]; Spanish: Islas Baleares[3][4][5] [ˈizlaz βaleˈaɾes])[6] are an archipelago of islands in Spain in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula.

Balearic Islands | |

|---|---|

Flag | |

| Anthem: La Balanguera | |

.svg.png) Location of the Balearic Islands within Spain | |

| Coordinates: 39°30′N 3°00′E | |

| Country | Spain |

| Capital | Palma de Mallorca |

| Government | |

| • Type | Devolved government in a constitutional monarchy |

| • Body | Govern de les Illes Balears |

| • President | Francina Armengol (PSIB-PSOE) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,992 km2 (1,927 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 17th (1.0% of Spain) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 1,107,220 |

| • Density | 220/km2 (570/sq mi) |

| • Pop. rank | 14th (2.3% of Spain) |

| Demonym(s) | Balearic balear (m/f) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | ES-IB |

| Area code | +34 971 |

| Official languages | Catalan and Spanish |

| Statute of Autonomy | 1 March 1982 1 March 2007 |

| Parliament | Balearic Parliament |

| Congress | 8 deputies (out of 350) |

| Senate | 7 senators (out of 266) |

| Website | www |

| 1.^ According to the current legislation the official name is in Catalan Illes Balears. | |

The four largest islands are Mallorca, Menorca, Ibiza, and Formentera. Many minor islands and islets are close to the larger islands, including Cabrera, Dragonera, and S'Espalmador. The islands have a Mediterranean climate, and the four major islands are all popular tourist destinations. Ibiza, in particular, is known as an international party destination, attracting many of the world's most popular DJs to its nightclubs.[7] The islands' culture and cuisine are similar to those of the rest of Spain but have their own distinctive features.

The archipelago forms an autonomous community and a province of Spain, with Palma de Mallorca as the capital. The 2007 Statute of Autonomy declares the Balearic Islands as one nationality of Spain.[8] The co-official languages in the Balearic Islands are Catalan and Spanish.

Etymology

The official name of the Balearic Islands in Catalan is Illes Balears, while in Spanish, they are known as the Islas Baleares. The term "Balearic" derives from Greek (Γυμνησίαι/Gymnesiae and Βαλλιαρεῖς/Balliareis).[9] In Latin, it is Baleares.

Of the various theories on the origins of the two ancient Greek and Latin names for the islands—Gymnasiae and Baleares—classical sources provide two.

According to the Lycophron's Alexandra verses, the islands were called Γυμνησίαι/Gymnesiae (γυμνός/gymnos, meaning naked in Greek) because its inhabitants were often nude, probably because of the year-round benevolent climate.

The Greek and Roman writers generally derive the name of the people from their skill as slingers (βαλεαρεῖς/baleareis, from βάλλω/ballo: ancient Greek meaning "to launch"), although Strabo regards the name as of Phoenician origin. He observed it was the Phoenician equivalent for lightly armoured soldiers the Greeks would have called γυμνῆτας/gymnetas.[10] The root bal does point to a Phoenician origin; perhaps the islands were sacred to the god Baal and the resemblance to the Greek root ΒΑΛ (in βάλλω/ballo) is accidental. Indeed, it was usual Greek practice to assimilate local names into their own language. But the common Greek name of the islands is not Βαλεαρεῖς/Baleareis, but Γυμνησίαι/Gymnesiai. The former was the name used by the natives, as well as by the Carthaginians and Romans,[11] while the latter probably derives from the light equipment of the Balearic troops γυμνῆται/gymnetae.[10]

Geology

The Balearic Islands are on a raised platform called the Balearic Promontory, and were formed by uplift. They are cut by a network of northwest to southeast faults.[12][13]

Geography and hydrography

The main islands of the autonomous community are Majorca (Mallorca), Menorca/Minorca (Menorca), Ibiza (Eivissa/Ibiza), and Formentera, all popular tourist destinations. Amongst the minor islands is Cabrera, the location of the Cabrera Archipelago Maritime-Terrestrial National Park.

The islands can be further grouped, with Majorca, Menorca, and Cabrera as the Gymnesian Islands (Illes Gimnèsies), and Ibiza and Formentera as the Pityusic Islands (Illes Pitiüses officially in Catalan), also referred to as the Pityuses (or sometimes informally in English as the Pine Islands). Many minor islands or islets are close to the biggest islands, such as Es Conills, Es Vedrà, Sa Conillera, Dragonera, S'Espalmador, S'Espardell, Ses Bledes, Santa Eulària, Plana, Foradada, Tagomago, Na Redona, Colom, L'Aire, etc.

The Balearic Front is a sea density regime north of the Balearic Islands on the shelf slope of the Balearic Islands, which is responsible for some of the surface-flow characteristics of the Balearic Sea.[14]

Climate

Located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, the Balearic Islands unsurprisingly have typical Mediterranean climates. The below-listed climatic data of the capital Palma are typical for the archipelago, with minor differences to other stations in Majorca, Ibiza, and Menorca.[15]

| Climate data for Palma de Mallorca, Port (1981–2010) (Satellite view) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.4 (59.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

27.1 (80.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.9 (53.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.2 (79.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

15.8 (60.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.5 (72.5) |

19.9 (67.8) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43 (1.7) |

37 (1.5) |

28 (1.1) |

39 (1.5) |

36 (1.4) |

11 (0.4) |

6 (0.2) |

22 (0.9) |

52 (2.0) |

69 (2.7) |

59 (2.3) |

48 (1.9) |

449 (17.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 53 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 167 | 170 | 205 | 237 | 284 | 315 | 346 | 316 | 227 | 205 | 161 | 151 | 2,779 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[16] | |||||||||||||

History

Ancient history

Little is recorded on the earliest inhabitants of the islands, though many legends exist. The story, preserved by Lycophron, that certain shipwrecked Greek Boeotians were cast nude on the islands, was evidently invented to account for the name Gymnesiae (Ancient Greek: Γυμνήσιαι). In addition, Diodorus Siculus writes that the Greeks called the islands Gymnesiae because the inhabitants were naked (γυμνοί) during the summer time.[17] Also, a tradition holds that the islands were colonised by Rhodes after the Trojan War.[10]

The islands had a very mixed population, of whose habits several strange stories are told. In some stories, the people were said to go naked or were clad only in sheepskins—whence the name of the islands (an instance of folk etymology)—until the Phoenicians clothed them with broad-bordered tunics. In other stories, they were naked only in the heat of summer.

Other legends allow that the inhabitants lived in hollow rocks and artificial caves, that they were remarkable for their love of women and would give three or four men as the ransom for one woman, that they had no gold or silver coin, and forbade the importation of the precious metals, so that those of them who served as mercenaries took their pay in wine and women instead of money. Their marriage and funeral customs, peculiar to Roman observers, are related by Diodorus Siculus (v. 18 book 6 chapter 5).

.jpg)

In ancient times, the islanders of the Gymnesian Islands (Illes Gimnèsies) constructed talayots, and were famous for their skill with the sling. As slingers, they served as mercenaries, first under the Carthaginians, and afterwards under the Romans. They went into battle ungirt, with only a small buckler, and a javelin burnt at the end, and in some cases tipped with a small iron point; but their effective weapons were their slings, of which each man carried three, wound round his head (Strabo p. 168; Eustath.), or, as seen in other sources, one round the head, one round the body, and one in the hand. (Diodorus) The three slings were of different lengths, for stones of different sizes; the largest they hurled with as much force as if it were flung from a catapult; and they seldom missed their mark. To this exercise they were trained from infancy, in order to earn their livelihood as mercenary soldiers. It is said that the mothers allowed their children to eat bread only when they had struck it off a post with the sling.[18]

The Phoenicians took possession of the islands in very early times;[19] a remarkable trace of their colonisation is preserved in the town of Mago (Maó in Menorca). After the fall of Carthage in 146 BC, the islands seem to have been virtually independent. Notwithstanding their celebrity in war, the people were generally very quiet and inoffensive.[20] The Romans, however, easily found a pretext for charging them with complicity with the Mediterranean pirates, and they were conquered by Q. Caecilius Metellus, thence surnamed Balearicus, in 123 BC.[21] Metellus settled 3,000 Roman and Spanish colonists on the larger island, and founded the cities of Palma and Pollentia.[22] The islands belonged, under the Roman Empire, to the conventus of Carthago Nova (modern Cartagena), in the province of Hispania Tarraconensis, of which province they formed the fourth district, under the government of a praefectus pro legato. An inscription of the time of Nero mentions the PRAEF. PRAE LEGATO INSULAR. BALIARUM. (Orelli, No. 732, who, with Muratori, reads pro for prae.) They were afterwards made a separate province, called Hispania Balearica, probably in the division of the empire under Constantine.[23]

The two largest islands (the Balearic Islands, in their historical sense) had numerous excellent harbours, though rocky at their mouth, and requiring care in entering them (Strabo, Eustath.; Port Mahon is one of the finest harbours in the world). Both were extremely fertile in all produce, except wine and olive oil.[24] They were celebrated for their cattle, especially for the mules of the lesser island; they had an immense number of rabbits, and were free from all venomous reptiles.[25] Amongst the snails valued by the Romans as a diet was a species from the Balearic isles called cavaticae because they were bred in caves.[26] Their chief mineral product was the red earth, called sinope, which was used by painters.[27] Their resin and pitch are mentioned by Dioscorides.[28] The population of the two islands is stated by Diodorus at 30,000.

The part of the Mediterranean east of Spain, around the Balearic Isles, was called Mare Balearicum,[29] or Sinus Balearicus.[30]

Medieval period

Late Roman and early Islamic eras

The Vandals under Genseric conquered the Islands sometime between 461 and 468 during their war on the Roman Empire. However, in late 533 or early 534, following the Battle of Ad Decimum, the troops of Belisarius reestablished control of the islands for the Romans. Imperial power receded precipitately in the western Mediterranean after the fall of Carthage and the Exarchate of Africa to the Umayyad Caliphate in 698, and in 707 the islands submitted to the terms of an Umayyad fleet, which allowed the residents to maintain their traditions and religion as well as a high degree of autonomy. Now nominally both Byzantine and Umayyad, the de facto independent islands occupied a strategic and profitable grey area between the competing religions and kingdoms of the western Mediterranean. The prosperous islands were thoroughly sacked by the Swedish Viking King Björn Ironside and his brother Hastein during their Mediterranean raid of 859–862.

In 902, the heavy use of the islands as a pirate base provoked the Emirate of Córdoba, nominally the island's overlords, to invade and incorporate the islands into their state. However, the Cordoban emirate disintegrated in civil war and partition in the early eleventh century, breaking into smaller states called taifa. Mujahid al-Siqlabi, the ruler of the Taifa of Dénia, sent a fleet and seized control of the islands in 1015, using it as the base for subsequent expeditions to Sardinia and Pisa. In 1050, the island's governor Abd Allah ibn Aglab rebelled and established the independent Taifa of Mallorca.

The Crusade against the Balearics

For centuries, the Balearic sailors and pirates had been masters of the western Mediterranean. But the expanding influence of the Italian maritime republics and the shift of power on the Iberian peninsula from the Muslim states to the Christian states left the islands vulnerable. A crusade was launched in 1113. Led by Ugo da Parlascio Ebriaco and Archbishop Pietro Moriconi of the Republic of Pisa, the expedition included 420 ships, a large army and a personal envoy from Pope Paschal II. In addition to the Pisans (who had been promised suzerainty over the islands by the Pope), the expedition included forces from the Italian cities of Florence, Lucca, Pistoia, Rome, Siena, and Volterra, from Sardinia and Corsica, Catalan forces under Ramon Berenguer, Hug II of Empúries, and Ramon Folc II of Cardona came from Spain and Occitan forces under William V of Montpellier, Aimery II of Narbonne, and Raymond I of Baux came from France. The expedition also received strong support from Constantine I of Logudoro and his base of Porto Torres.

The crusade sacked Palma in 1115 and generally reduced the islands, ending its period as a great sea power, but then withdrew. Within a year, the now shattered islands were conquered by the Berber Almoravid dynasty, whose aggressive, militant approach to religion mirrored that of the crusaders and departed from the island's history as a tolerant haven under Cordoba and the taifa. The Almoravids were conquered and deposed in North Africa and on the Iberian Peninsula by the rival Almohad Dynasty of Marrakech in 1147. Muhammad ibn Ganiya, the Almoravid claimant, fled to Palma and established his capital there. His dynasty, the Banu Ghaniya, sought allies in their effort to recover their kingdom from the Almohads, leading them to grant Genoa and Pisa their first commercial concessions on the islands. In 1184, an expedition was sent to recapture Ifriqiya (the coastal areas of what is today Tunisia, eastern Algeria, and western Libya) but ended in defeat. Fearing reprisals, the inhabitants of the Balearics rebelled against the Almoravids and accepted Almohad suzerainty in 1187.

Reconquista

On the last day of 1229, King James I of Aragon captured Palma after a three-month siege. The rest of Mallorca quickly followed. Menorca fell in 1232 and Ibiza in 1235. In 1236, James traded most of the islands to Peter I, Count of Urgell for Urgell, which he incorporated into his kingdom. Peter ruled from Palma, but after his death without issue in 1258, the islands reverted by the terms of the deal to the Crown of Aragon.

James died in 1276, having partitioned his domains between his sons in his will. The will created a new Kingdom of Mallorca from the Balearic islands and the mainland counties of Roussillon or Montpellier, which was left to his son James II. However, the terms of the will specified that the new kingdom be a vassal state to the Crown of Aragon, which was left to his older brother Peter. Chafing under the vassalage, James joined forces with the Pope Martin IV and Philip III of France against his brother in the Aragonese Crusade, leading to a 10-year Aragonese occupation before the islands were restored in the 1295 Treaty of Anagni. The tension between the kingdoms continued through the generations until James' grandson James III was killed by the invading army of Peter's grandson Peter IV at the 1349 Battle of Llucmajor. The Balearic Islands were then incorporated directly into the Crown of Aragon.

Modern period

In 1469, Ferdinand II of Aragon (king of Aragon) and Isabella I of Castile (queen of Castile) were married. After their deaths, their respective territories (until then governed separately) were governed jointly, in the person of their grandson, the Emperor Charles V. This can be considered the foundation of the modern Spanish state, albeit a decentralised one wherein the various component territories within the united crowns retained their particular historic laws and privileges.

The Balearic Islands were frequently attacked by Ottomans and Barbary pirates from North Africa; Formentera was even temporarily abandoned by its population. In 1514, 1515 and 1521, the coasts of the Balearic Islands and the Spanish mainland were raided by Turkish privateers under the command of the Ottoman admiral, Hayreddin Barbarossa. The Balearic Islands were ravaged in 1558 by Ottoman corsair Turgut Reis, and 4,000 people were taken into slavery.[31]

The island of Menorca was a British dependency for most of the 18th century as a result of the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. This treaty—signed by the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Portugal as well as the Kingdom of Spain, to end the conflict caused by the War of the Spanish Succession—gave Gibraltar and Menorca to the Kingdom of Great Britain, Sardinia to Austria (both territories had been part of the Crown of Aragon for more than four centuries), and Sicily to the House of Savoy. In addition, Flanders and other European territories of the Spanish Crown were given to Austria. The island fell to French forces, under Armand de Vignerot du Plessis in June 1756 and was occupied by them for the duration of the Seven Years' War.

The British re-occupied the island after the war but, with their military forces diverted away by the American War of Independence, it fell to a Franco-Spanish force after a seven-month siege (1781–82). Spain retained it under the Treaty of Paris in 1783. However, during the French Revolutionary Wars, when Spain became an ally of France, it came under French rule.

Menorca was finally returned to Spain by the Treaty of Amiens during the French Revolutionary Wars, following the last British occupation, which lasted from 1798 to 1802. The continued presence of British naval forces, however, meant that the Balearic Islands were never occupied by the French during the Napoleonic Wars.

Culture

Cuisine

The cuisine of the islands can be grouped as part of wider Catalan, Spanish or Mediterranean cuisines. It features much pastry, cheese, wine, pork and seafood. Sobrassada is a local pork sausage. Lobster stew from Menorca, is one of their most well-sought after dishes, attracting even King Juan Carlos I to the islands.[32] Mayonnaise is said to originate from the Menorcan city of Maó,[33] which also produces its own cheese. Local pastries include Ensaimada, Flaó and Coca.

Languages

Both Catalan and Spanish are official languages in the islands. Catalan is designated as a "llengua pròpia", literally "own language" in its statute of autonomy. The Balearic dialect features several differences from standard Catalan. Practically all residents of the Balearic Islands speak Spanish fluently. In 2003 74.6% of the Islands' residents also knew how to speak Catalan and 93.1% could understand it.[34] Other languages, such as English, German, French and Italian, are often spoken by locals, especially those who work in the tourism industry.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 311,649 | — |

| 1910 | 326,063 | +4.6% |

| 1920 | 338,894 | +3.9% |

| 1930 | 365,512 | +7.9% |

| 1940 | 407,497 | +11.5% |

| 1950 | 422,089 | +3.6% |

| 1960 | 443,327 | +5.0% |

| 1970 | 558,287 | +25.9% |

| 1981 | 655,945 | +17.5% |

| 1991 | 708,138 | +8.0% |

| 2001 | 841,669 | +18.9% |

| 2011 | 1,100,513 | +30.8% |

| 2017 | 1,150,839 | +4.6% |

| Source: [35] | ||

| Population in the Balearic Islands (2005)[36] Insular council (official name in Catalan and equivalent in Spanish) |

Population | % total of Balearic Islands | Density (inhabitants/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Majorca (Mallorca/Mallorca) | 777,821 | 79.12% | 214.84 |

| Ibiza (Eivissa/Ibiza) | 111,107 | 11.30% | 193.22 |

| Menorca (Menorca/Menorca) | 86,697 | 8.82% | 124.85 |

| Formentera (Formentera/Formentera) | 7,506 | 0.76% | 90.17 |

Circa 2017 there were 1,115,999 residents of the Balearics; 16.7% of the islands' population were foreign (non-Spanish). At that time the islands had 23,919 Moroccans, 19,209 Germans, 16,877 Italians, and 14,981 British registered in town halls. The next-largest foreign groups were the Romanians; the Bulgarians; the Argentines, numbering at 6,584; the French; the Colombians; and the Ecuadoreans, numbering at 5,437.[37]

Circa 2016 the islands had 1,107,220 total residents; the figures of Germans and British respectively were 20,451 and 16,134. Between 2016 and 2017 people from other parts of Spain moved to the Balearics, while the foreign population declined by 2,000. In 2007 there were 29,189 Germans, 19,803 British, 17,935 Moroccans, 13,100 Ecuadoreans, 11,933 Italians, and 11,129 Argentines. The numbers of Germans, British, and South Americans declined between 2007 and 2017 while the largest-increasing populations were the Moroccans, Italians, and Romanians.[37]

Administration

Each one of the three main islands is administered, along with its surrounding minor islands and islets, by an insular council (consell insular in Catalan) of the same name. These four insular councils are the first level of subdivision in the autonomous community (and province) of the Baleares.

Before the administrative reform of 1977, the two insular councils of Ibiza and Formentera were forming in a single one (covering the whole group of the Pitiusic Islands).

This level is further subdivided into six comarques only in the insular council of Mallorca; the three other insular councils are not subdivided into separate comarques, but are themselves assimilated each one to a comarca covering the same territory as the insular council.

These nine comarques are then subdivided into municipalities (municipis), with the exception of Formentera, which is at the same time an insular council, a comarca, and a municipality.

Note that the maritime and terrestrial natural reserves in the Balearic Islands are not owned by the municipalities, even if they fall within their territory, but are owned and managed by the respective insular councils from which they depend.

Those municipalities are further subdivided into civil parishes (parròquies), that are slightly larger than the traditional religious parishes, themselves subdivided (only in Ibiza and Formentera) into administrative villages (named véndes in Catalan); each vénda is grouping several nearby hamlets (casaments) and their immediate surrounding lands—these casaments are traditionally formed by grouping together several cubic houses to form a defensive parallelepiped with windows open to the east (against heat), sharing their collected precious water resources, whose residents are deciding and planning some common collective works.

However, these last levels of subdivisions of municipalities do not have their own local administration: they are mostly as the natural economical units for agricultural exploitation (and consequently referenced in local norms for constructions and urbanisation as well) and are the reference space for families (so they may be appended to the names of peoples and their land and housing properties) and are still used in statistics. Historically, these structures have been used for defensive purpose as well, and were more tied to the local Catholic church and parishes (notably after the Reconquista).

Economy

The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the autonomous community was 32.5 billion euros in 2018, accounting for 2.7% of Spanish economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 29,700 euros or 98% of the EU27 average in the same year.[38]

Transport

Water transport

There are approximately 79 ferries between Mallorca and other destinations every week, most of them to mainland Spain.

- Baleària

- to the Balearic Islands from Dénia, Valencia and Barcelona

- Trasmediterránea

- Mainland-Baleares: regular lines, in both directions, from:

- Barcelona to Palma de Mallorca, Ibiza and Mahón.

- Valencia to Palma de Mallorca, Ibiza and Mahón.

- Gandia to Palma de Mallorca and Ibiza.

- Mainland-Baleares: regular lines, in both directions, from:

Sport

The islands' most prominent football club is RCD Mallorca from Palma, currently playing in the first-tier La Liga after promotion in 2019. Founded in 1916, it is the oldest club in the islands, and won its only Copa del Rey title in 2003[39] and was the runner-up in the 1999 European Cup Winners' Cup.[40]

Tennis player Rafael Nadal, winner of 19 Grand Slam single titles, and former world no. 1 tennis player Carlos Moyá are both from Majorca. Rafael Nadal's uncle, Miguel Ángel Nadal, is a former Spanish international footballer. Other famous sportsmen include basketball player Rudy Fernández and motorcycle road racer Jorge Lorenzo, who won the 2010, 2012 and 2015 MotoGP World Championships.

Whale watching is also expected for expanding future tourism of the islands.[41][42]

Ibiza also recently became one of the world's top yachting hubs attracting a wide among of charter yachts[43] and the world's second most expensive marina in the world.

Image gallery

View of the Serra de Tramuntana mountain range, Majorca

View of the Serra de Tramuntana mountain range, Majorca Port de Sóller on the northwest coast of Majorca

Port de Sóller on the northwest coast of Majorca La Almudaina was a royal palace of the kings of Majorca, Aragon and Spain

La Almudaina was a royal palace of the kings of Majorca, Aragon and Spain- Valldemossa Charterhouse was royal palace of the king Sancho of Majorca

See also

- Battle of Majorca

- Formentera

- Ibiza

- Ibiza (town) (Vila d'Eivissa or Vila)

- List of butterflies of Menorca

- List of dragonflies of Menorca

- List of municipalities in Balearic Islands

- List of Presidents of the Balearic Islands Parliament

- Mallorca

- Menorca

- Palma de Mallorca

- List of Presidents of the Balearic Islands

Notes and references

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Roach, Peter (2011). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15253-2.

- "Ley 3/1986, de 19 de abril, de normalización linguística". Boe.es. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "Ley 13/1997, de 25 de abril, por la que pasa a denominarse oficialmente Illes Balears la Provincia de Baleares". Boe.es. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- "Ley Orgánica 1/2007, de 28 de febrero, de reforma del Estatuto de Autonomía de las Illes Balears". Boe.es. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- In isolation, these words are pronounced [ˈizlas] and [baleˈaɾes].

- "The Party Island of Ibiza". www.vice.com.

- Estatut d'Autonomia de les Illes Balears, Llei Orgànica 1/2007, article 1r

- Diod. v. 17, Eustath. ad Dion. 457; Baliareis – Βαλιαρεῖς, Baliarides – Βαλιαρίδες, Steph. B.; Balearides – Βαλεαρίδες, Strabo; Balliarides – Βαλλιαρίδες, Ptol. ii. 6. § 78; Baleariae – Βαλεαρίαι Agathem.

- Strab. xiv. p. 654; Plin. l. c "The Rhodians, like the Baleares, were celebrated slingers"

Sil. Ital. iii. 364, 365: "Jam cui Tlepolemus sator, et cui Lindus origo, Funda bella ferens Balearis et alite plumbo." - Plin.; Agathem.; Dion Cass. ap. Tzetz. ad Lycophr. 533; Eustath.

- Roberts, David G.; A. W. Bally (2012). "Regional Geology and Tectonics: Phanerozoic Passive Margins, Cratonic Basins and Global Tectonic Maps, Volume 1". Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- "History of Mallorca" (PDF). 2007–2012. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2011. Balearic Sea. Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. P. Saundry & C. J. Cleveland. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington D.C.

- "Standard climate values, Illes Balears". Aemet.es. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "Guía resumida del clima en España (1981–2010)". Archived from the original on 18 November 2012.

- Diodorus Siculus, Library, §5.17.1

- Strabo; Diod.; Flor. iii. 8; Tzetzes ad Lycophron.

- Strabo iii. pp. 167, 168.

- Strabo; but Florus gives them a worse character, iii. 8.

- Livy Epit. Ix.; Freinsh. Supp. lx. 37; Florus, Strabo ll. cc.

- Strabo, Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder.

- Notitia Dignitatum Occid. c. xx. vol. ii. p. 466, Böcking.

- Aristot. de Mir. Ausc. 89; Diodorus, but Pliny praises their wine as well as their corn, xiv. 6. s. 8, xviii. 7. s. 12: the two writers are speaking, in fact, of different periods.

- Strabo, Mela; Pliny l. c., viii. 58. s. 83, xxxv. 19. s. 59; Varro, R. R. iii. 12; Aelian, H. A. xiii. 15; Gaius Julius Solinus 26.

- Pliny xxx. 6. s. 15.

- Pliny xxxv. 6. s. 13; Vitruv. vii. 7.

- Materia Medica i. 92.

- τὸ Βαλλεαρικὸν πέλαγος, Ptol. ii 4. § 3.

- Flor. iii. 6. § 9.

- Carr, Matthew, Blood and Faith: the Purging of Muslim Spain (Leiden, 1968), p. 120.

- Curiosidades turísticas en Menorca. Sobreespana.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- "Mayonnaise". Andalucia For Holidays. 6 July 2013. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- Estad. Ibestat.cat. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- "1.1.1.01 Población por año de nacimiento, isla de residencia y sexo". Institut d'Estadística de las Illes Balears (in Spanish). 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- Fuente: INE Instituto Nacional de Estadística de España (01-01-2005)

- "British and German foreign communities decreasing". Majorca Daily Bulletin. 19 January 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- Spain Cups 2002/03. Rsssf.com (2004-02-03). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- UEFA Champions League, Cup Winners Cup, UEFA Cup 1998–99. Rsssf.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- "NEWS – Balearic highway for whales and dolphins". Ibiza Spotlight. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- Unidad Editorial Internet (3 March 2012). "Una ballena se da un festín en Ibiza". Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- "Yacht Charter Ibiza | Boat Charter Ibiza | Magenta Yachts Brokers". Magenta Yachts. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

References

- Guide to yacht clubs and marinas in Spain: Costa Blanca, Costa del Azahar, Islas Baleares (Madrid: Ministry of Transportation, Tourism and Communications, General Office of the Secretary of Tourism, General Office of Tourism Companies and Activities, 1987)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Balearic Islands. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Balearic Islands. |

- Lins, Joseph (1907). . Catholic Encyclopedia. 2.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Balearic Islands at Curlie