Boeing 737

The Boeing 737 is a narrow-body aircraft produced by Boeing Commercial Airplanes at its Renton Factory in Washington. Developed to supplement the Boeing 727 on short and thin routes, the twinjet retains the 707 fuselage cross-section and nose with two underwing turbofans. Envisioned in 1964, the initial 737-100 made its first flight in April 1967 and entered service in February 1968 with Lufthansa. The lengthened 737-200 entered service in April 1968. It evolved through four generations, offering several variants for 85 to 215 passengers.

| Boeing 737 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Boeing 737-200, the first mass-produced 737 model, in operation with South African Airways in 2007 | |

| Role | Narrow-body aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Boeing Commercial Airplanes |

| First flight | April 9, 1967 |

| Introduction | February 10, 1968, with Lufthansa |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Southwest Airlines Ryanair United Airlines American Airlines |

| Produced | 1966–present |

| Number built | 10,580 as of June 2020[1] |

| Unit cost | |

| Variants | Boeing T-43 |

| Developed into | Boeing 737 Classic Boeing 737 Next Generation Boeing 737 MAX |

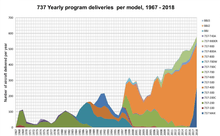

The -100/200 original variants were powered by Pratt & Whitney JT8D low-bypass engines and offered seating for 85 to 130 passengers. Launched in 1980 and introduced in 1984, the 737 Classic -300/400/500 variants were re-engined with CFM56-3 turbofans and offered 110 to 168 seats. Introduced in 1997, the 737 Next Generation (NG) -600/700/800/900 variants have updated CFM56-7s, a larger wing and an upgraded glass cockpit, and seat 108 to 215 passengers. The latest generation, the 737 MAX -7/8/9/10, powered by improved CFM LEAP-1B high bypass turbofans and accommodating 138 to 204 people, entered service in 2017. Boeing Business Jet versions are produced since the 737NG, as well as military models.

As of December 2019, 15,156 Boeing 737s have been ordered and 10,571 delivered. Initially, its main competitor was the McDonnell Douglas DC-9, followed by its MD-80/MD-90 derivatives. It was the highest-selling commercial aircraft until being surpassed by the competing Airbus A320 family in October 2019, but maintaining the record in total deliveries. The 737 MAX, designed to compete with the A320neo was grounded worldwide in March 2019 following two fatal crashes. After system improvement required by FAA, the aircraft had completed a series of recertification test flights aim for ungrounding in the midyear 2020.

Development

_on_its_maiden_flight.jpg)

Initial design

Boeing had been studying short-haul jet aircraft designs, and saw a need for a new aircraft to supplement the 727 on short and thin routes.[4] Preliminary design work began on May 11, 1964,[5] based on research that indicated a market for a fifty to sixty passenger airliner flying routes of 50 to 1,000 mi (100 to 1,600 km).[4][6]

The initial concept featured podded engines on the aft fuselage, a T-tail as with the 727, and five-abreast seating, but engineer Joe Sutter instead placed the engines under the wings to lighten the structure and enabling the fuselage to be widened to six-abreast seating.[7] The nacelles were mounted directly to the underside of the wings to allow the landing gear to be shortened, lowering the fuselage and enabling easier baggage and passenger access.[8] Mounting the engines on the wings also allowed the horizontal stabilizer to be attached to the rear fuselage rather than the tail fin.[9] Many designs for the engine attachment strut were tested in the wind tunnel and the optimal shape for high speed was found to be one which was relatively thick, filling the narrow channels formed between the wing and the top of the nacelle, particularly on the outboard side.

At the time, Boeing was far behind its competitors; rival aircraft in development, the BAC-111, Douglas DC-9, and Fokker F28 were already into flight certification.[10] To expedite development, Boeing used 60% of the structure and systems of the existing 727, the most notable being the fuselage cross-section. This fuselage permitted six-abreast seating compared to the rival aircraft's five-abreast layout.[11]

The proposed wing airfoil sections were based on those of the 707 and 727, but somewhat thicker; altering these sections near the nacelles achieved a substantial drag reduction at high Mach numbers.[12] The engine chosen was the Pratt & Whitney JT8D-1 low-bypass ratio turbofan engine, delivering 14,500 lbf (64 kN) thrust.[13]

The concept design was presented in October 1964 at the Air Transport Association maintenance and engineering conference by chief project engineer Jack Steiner, where its elaborate high-lift devices raised concerns about maintenance costs and dispatch reliability.[7][7]

Launch

The launch decision for the $150 million development was made by the board on February 1, 1965. Lufthansa became the launch customer on February 19, 1965,[11] with an order for 21 aircraft, worth $67 million[10] after the airline had been assured by Boeing that the 737 project would not be canceled.[14] Consultation with Lufthansa over the previous winter had resulted in the seating capacity being increasd to 100.[11] It competed primarily with the McDonnell Douglas DC-9, then its MD-80/MD-90 derivatives.

On April 5, 1965, Boeing announced an order by United Airlines for 40 737s. United wanted a slightly larger capacity than the 737-100, so the fuselage was stretched 36 in (91 cm) ahead of, and 40 in (102 cm) behind the wing.[9] The longer version was designated the 737-200, with the original short-body aircraft becoming the 737-100.[15] Detailed design work continued on both variants simultaneously.

Introduction

After the first flight on April 9, 1967, piloted by Brien Wygle and Lew Wallick.[16] and seveal test flights, the FAA issued Type Certificate A16WE certifying the 737-100 for commercial flight on December 15, 1967.[17][18] It was the first aircraft to have, as part of its initial certification, approval for Category II approaches,[19] which refers to a precision instrument approach and landing with a decision height between 98 to 197 feet (30 to 60 m).[20] Lufthansa received its first aircraft on December 28, 1967 and on February 10, 1968, became the first non-American airline to launch a new Boeing aircraft.[17] Lufthansa was the only significant customer to purchase the 737-100 and only 30 aircraft were produced.[21]

The 737-200 had its maiden flight on August 8, 1967 and was certified by the FAA on December 21, 1967.[18][22] The inaugural flight for United Airlines took place on April 28, 1968, from Chicago to Grand Rapids, Michigan.[17] The lengthened -200 was widely preferred over the -100 by airlines.[23] The improved version, the 737-200 Advanced, was introduced into service by All Nippon Airways on May 20, 1971.[24]

Sales were low in the early 1970s[25] and, after a peak of 114 deliveries in 1969, only 22 737s were shipped in 1972 with 19 in backlog. The US Air Force saved the program by ordering T-43s, which were modified Boeing 737-200s. African airline orders kept the production running until the 1978 US Airline Deregulation Act, which improved demand for six-abreast narrow-body aircraft. Demand further increased after being re-engined with the CFM56.[7] The 737 went on to become the highest-selling commercial aircraft until surpassed by the competing Airbus A320 family in October 2019, but maintains the record in total deliveries.

Production

The first of six -100 prototypes rolled out in December 1966. Assembly commenced on premises adjacent to Boeing Field (now officially named King County International Airport) because the factory at Renton was filled to capacity with the production of the 707 and 727. In late 1970, after 271 737s had been built, production was moved to Renton.[14]

The fuselage, built in Wichita, Kansas, was initially delivered for assembly in two sections but, since the 737 Next Generation, production efficiency has been improved by shipping the entire fuselage complete.[26] The fuselage is joined with the wings and landing gear and then moves down the assembly line for the engines, avionics, and interiors. After its rollout, all systems are tested before the maiden flight to Boeing Field, where it is painted and fine-tuned for delivery.[27]

Outsourcing

In 1990, Boeing was producing 80% of key-components in house, including wings, fuselage and tail assemblies but much of this has been contracted out to other suppliers.[25] In 2005, Boeing sold its commercial aircraft plants in Kansas and Oklahoma, which together was the largest in-house aircraft-component maker within Boeing.[28] The plants at the time produced parts for every Boeing commercial jet except the 717, supplied fuselage sections and wing elements for four Boeing jets in addition to the 787, employing 7,200 and 1,300 respectively.[28] By outsourcing, Boeing achieved better financial returns and redistributed the financial risk. By 2012, suppliers, particularly for 737NG series, were responsible for producing the bulk of the airframe, while in-house production accounted for less than 40% of a plane's parts.

A significant portion of fuselage assembly, previously done by Boeing, is now done by Spirit AeroSystems, which purchased some of Boeing's assets in Wichita.[29][30]

Further developments

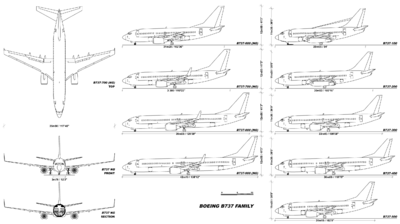

The original 737 continued to be developed into thirteen major variants. These were later divided into what has become known as the four generations of the 737:

- The first "Original" generation: the 737-100 and -200, also the military T-43 and C-43, launched February 1965.

- The second "Classic" generation: 737-300, -400 and 500 series, launched in 1979.

- The third generation "NG" series: 737-600, -800 and 900 series, also the military C-40 and P-8, launched late 1993.

- The fourth generation 737 MAX series, launched August 2011.

Replacement

Boeing had discussed replacing the 737 with a clean sheet aircraft since 2006. The project's working name was the Boeing Y1 and development was planned to follow the already completed Boeing Y2, the Boeing 787 Dreamliner.[31] However, a decision on this replacement was postponed to after 2011.[32] In November 2014, Boeing announced a plan to develop the clean sheet aircraft to replace the 737 by 2030. The conceived aircraft was to have a similar fuselage cross section to 737 but made use of the advanced composite technology developed for the Dreamliner.[33] Boeing also considered a parallel development along with the 757 replacement, similar to the development of the 757 and 767 in the 1970s.[34]

In the late 2010s, Boeing worked on a medium-range Boeing New Midsize Airplane (NMA) with two variants seating 225 or 275 passengers and targeting the same market segment as the 737 MAX 10 and the Airbus A321 neo.[35] A Future Small Airplane (FSA) was also touted during this period.[36] The NMA project was set aside in January 2020, as Boeing focused on returning the 737 MAX to service and announced that it would be taking a new approach to future projects.[37]

Design

The 737 continued to evolve into many variants but still remains recognisable as the 737. These are divided into four generations but all are based on the same basic design.

Airframe

The fuselage cross section and nose is derived from that of the Boeing 707 and Boeing 727. Early 737 cockpits also inherited the "eyebrow windows" positioned above the main glareshield, which were a feature of the original 707 and 727[38] to allow for better crew visibility.[39] Contrary to popular belief, these windows were not intended for celestial navigation[40] (only the military T-43A had a sextant port for star navigation, which the civilian models lacked.[41] With modern avionics, the windows became redundant, and many pilots actually placed newspapers or other objects in them to block out sun glare. They were eliminated from the 737 cockpit design in 2004, although they are still installed on customer request.[42] The eyebrow windows were sometimes removed and plugged, usually during maintenance overhauls, and can be distinguished by the metal plug which differs from the smooth metal in later aircraft that were not originally fitted with the windows.[42]

The 737's main landing gear, under the wings at mid-cabin, rotates into wheel wells in the aircraft's belly. The legs are covered by partial doors, and "brush-like" seals aerodynamically smooth (or "fair") the wheels in the wells. The sides of the tires are exposed to the air in flight. "Hub caps" complete the aerodynamic profile of the wheels. It is forbidden to operate without the caps, because they are linked to the ground speed sensor that interfaces with the anti-skid brake system. The dark circles of the tires are clearly visible when a 737 takes off, or is at low altitude.[43]

From July 2008 the steel landing gear brakes on new NGs were replaced by Messier-Bugatti carbon brakes, achieving weight savings up to 550–700 lb (250–320 kg) depending on whether standard or high-capacity brakes.[44] On a 737-800 this gives a 0.5% improvement in fuel efficiency.[45]

737s are not equipped with fuel dump systems. The original design was too small to require this, and adding a fuel dump system to the later, larger variants would have incurred a large weight penalty. Boeing instead demonstrated an "equivalent level of safety". Depending upon the nature of the emergency, 737s either circle to burn off fuel or land overweight. If the latter is the case, the aircraft is inspected by maintenance personnel for damage and then returned to service if none is found.[46][47]

The original 737 with JT8D engines that span the entire wing chord

The original 737 with JT8D engines that span the entire wing chord The 737 Classic with stubbier and wider CFM56s ahead of the wings

The 737 Classic with stubbier and wider CFM56s ahead of the wings The 737NG has a 25% larger and 16 ft (5 m) wider wing

The 737NG has a 25% larger and 16 ft (5 m) wider wing The 737 MAX has larger CFM LEAP engines with chevrons

The 737 MAX has larger CFM LEAP engines with chevrons

Engines

Engines on the 737 Classic series (−300, −400, −500) and Next-Generation series (−600, −700, −800, −900) do not have circular inlets like most aircraft but rather a planform on the lower side, which has been dictated largely by the need to accommodate ever larger engine diameters. The 737 Classic series featured CFM56 high bypass turbofan engines, which yielded significant gains in fuel economy and a reduction in noise over the JT8D low bypass engines used on the 737 Original series (−100 and −200), but also posed an engineering challenge given the low ground clearance of the 737 aircraft family. Boeing and engine supplier CFM International (CFMI) solved the problem by placing the engine ahead of (rather than below) the wing, and by moving engine accessories to the sides (rather than the bottom) of the engine pod, giving the 737 Classic and later generations a distinctive non-circular air intake.[48]

The wing also incorporated changes for improved aerodynamics. The engines' accessory gearbox was moved from the 6 o'clock position under the engine to the 4 o'clock position (from a front/forward looking aft perspective). This side-mounted gearbox gives the engine a somewhat rounded triangular shape. Because the engine is close to the ground, 737-300s and later models are more prone to engine foreign object damage (FOD). The improved, higher pressure ratio CFM56-7 turbofan engine on the 737 Next Generation is 7% more fuel-efficient than the previous CFM56-3 on the 737 Classic with the same bypass ratio. The newest 737 variants, the 737 MAX series, feature LEAP-1B engines from CFMI with a 68 inches (1.73 m) fan diameter. These engines were expected to be 10-12% more efficient than the CFM56-7B engines on the 737 Next Generation series.[49]

_JT8D.jpg)

Flight systems

The 737 is unusual in that it still uses a hydro-mechanical flight control system, similar to the Boeing 707 and typical of the period, that transmits pilot commands to control surfaces by steel cables run through the fuselage and wings rather than by an electrical fly-by-wire system as used in all of the Airbus fleet and all later Boeing models.[50] This has been raised as a safety issue because of the impracticality of duplicating such a mechanical cable-based system in the way that an electrical or electronic system can be. This leaves the flight controls as a single point of failure, for example by metal fragments from an uncontained engine failure penetrating the wings or fuselage.[51]

The primary flight controls have mechanical backups. In the event of total hydraulic system failure or double engine failure, they will automatically and seamlessly revert to control via servo tab. In this mode, the servo tabs aerodynamically control the elevators and ailerons; these servo tabs are in turn controlled by cables running to the control yoke. The pilot's muscle forces alone control the tabs.

The 737 Next Generation series introduced a six-screen LCD glass cockpit with modern avionics but designed to retain crew commonality with previous 737 generations.[52]

Aerodynamic

The Original -100 and -200 series were built without wingtip devices but these were later introduced to improve fuel efficiency. The 737 has evolved four winglet types: the 737-200 Mini-winglet, 737 Classic/NG Blended Winglet, 737 Split Scimitar Winglet, and 737 MAX Advanced Technology Winglet.[42] The 737-200 Mini-winglets are part of the Quiet Wing Corp modification kit that received certification in 2005.[42]

Blended winglets were standard on the 737 NG and are available for retrofit on 737 Classic models. These winglets stand approximately 8 feet (2.4 m) tall and are installed at the wing tips. They improve fuel efficiency by up to 5% through lift-induced drag reduction achieved by moderating wingtip vortices.[53][54]

Split Scimitar winglets became available in 2014 for the 737-800, 737-900ER, BBJ2 and BBJ3, and in 2015 for the 737-700, 737-900 and BBJ1.[55] Split Scimitar winglets were developed by Aviation Partners Inc. (API), the same Seattle based corporation that developed the blended winglets; the Split Scimitar winglets produce up to a 5.5% fuel savings per aircraft compared to 3.3% savings for the blended winglets. Southwest Airlines flew their first flight of a 737-800 with Split Scimitar winglets on April 14, 2014.[56] The next generation 737, 737 MAX, will feature an Advanced Technology (AT) Winglet that is produced by Boeing. The Boeing AT Winglet resembles a cross between the Blended Winglet and the Split Scimitar Winglet.[57]

An optional Enhanced Short Runway Package was developed for use on short runways.

_winglet.jpg)

Interior

The first generation Original series 737 cabin was replaced for the second generation Classic series with a design based on the Boeing 757 cabin. The Classic cabin was then redesigned once more for the third, Next Generation, 737 with a design based on the Boeing 777 cabin. Boeing later offered the redesigned Sky Interior on the NG. The principle features of the Sky Interior include: sculpted sidewalls, redesigned window housings, increased headroom and LED mood lighting,[58][59] larger pivot-bins based on the 777 and 787 designs and generally more luggage space,[59] and claims to have improved cabin noise levels by 2–4 dB.[58] The first 737 equipped Boeing Sky Interior was delivered to Flydubai in late 2010.[58] Continental Airlines,[60][61] Alaska Airlines,[62] Malaysia Airlines,[63] and TUIFly have also received Sky Interior-equipped 737s.[64]

Variants (generations)

737 Original (first generation)

The "Original" models consisted of the 737-100, 737-200 and the 200 Advanced:

737-100

The initial model was the 737-100, which was launched in February 1965. The -100 was rolled out on January 17, 1967, had its first flight on April 9, 1967, and entered service with Lufthansa in February 1968. The aircraft is the smallest variant of the 737. A total of 30 737-100s were ordered and delivered; the final commercial delivery took place on October 31, 1969, to Malaysia–Singapore Airlines. No 737-100s remain in commercial service. The original Boeing prototype was last operated by NASA, retired more than 30 years after its maiden flight and is on exhibit in the Museum of Flight in Seattle.[65]

The original engine nacelles incorporated thrust reversers taken from the 727 outboard nacelles. They proved to be relatively ineffective and tended to lift the aircraft up off the runway when deployed. This reduced the downforce on the main wheels thereby reducing the effectiveness of the wheel brakes. In 1968, an improvement to the thrust reversal system was introduced.[66] A 48-inch tailpipe extension was added and new, target-style, thrust reversers were incorporated. The thrust reverser doors were set 35 degrees away from the vertical to allow the exhaust to be deflected inboard and over the wings and outboard and under the wings. The improvement became standard on all aircraft after March 1969, and a retrofit was provided for active aircraft. Boeing fixed the drag issue by introducing new longer nacelle/wing fairings, and improved the airflow over the flaps and slats. The production line also introduced an improvement to the flap system, allowing increased use during takeoff and landing. All these changes gave the aircraft a boost to payload and range, and improved short-field performance.[17] In May 1971, after aircraft #135, all improvements, including more powerful engines and a greater fuel capacity, were incorporated into the 737-200, giving it a 15% increase in payload and range over the original -200s.[19] This became known as the 737-200 Advanced, which became the production standard in June 1971.[67]

737-200

The 737-200 was a 737-100 with an extended fuselage, launched by an order from United Airlines in 1965. The -200 was rolled out on June 29, 1967, and entered service with United in April 1968. The 737-200 Advanced is an improved version of the -200, introduced into service by All Nippon Airways on May 20, 1971.[24] The -200 Advanced has improved aerodynamics, automatic wheel brakes, more powerful engines, more fuel capacity, and longer range than the -100.[68] Boeing also provided the 737-200C (Combi), which allowed for conversion between passenger and cargo use and the 737-200QC (Quick Change), which facilitated a rapid conversion between roles. The 1,095th and last delivery of a -200 series aircraft was in August 1988 to Xiamen Airlines.[1][69]

With a gravel kit modification (features preventing foreign object damage), the 737-200 can use unimproved or unpaved landing strips, such as gravel runways, that other similarly-sized jet aircraft cannot. Gravel-kitted 737-200 Combis are currently used by Canadian North, First Air, Air Inuit, Nolinor, and Air North in northern Canada where gravel runways are common. For many years, Alaska Airlines made use of gravel-kitted 737-200s to serve Alaska's many unimproved runways across the state.[70]

Nineteen 737-200s, designated T-43, were used to train aircraft navigators for the U.S. Air Force. Some were modified into CT-43s, which are used to transport passengers, and one was modified as the NT-43A Radar Test Bed. The first was delivered on July 31, 1973 and the last on July 19, 1974. The Indonesian Air Force ordered three modified 737-200s, designated Boeing 737-2x9 Surveiller. They were used as Maritime reconnaissance (MPA)/transport aircraft, fitted with SLAMMAR (Side-looking Multi-mission Airborne Radar). The aircraft were delivered between May 1982 and October 1983.[71]

Many 737-200s have been phased out or replaced by newer 737 versions. After 40 years, in March 2008, the final 737-200 aircraft in the U.S. flying scheduled passenger service were phased out, with the last flights of Aloha Airlines.[72] The variant still sees regular service through North American charter operators such as Sierra Pacific.[73]

In July 2019, there were a combined 46 Boeing 737-200s in service, mostly with "second and third tier" airlines, and those of developing nations.[74]

In 1970, Boeing received only 37 orders. Facing financial difficulties, Boeing considered closing the 737 production-line and selling the design to Japanese aviation companies.[14] After the cancellation of the Boeing Supersonic Transport, and scaling back of 747 production, enough funds were freed up to continue the project.[66] In a bid to increase sales by offering a variety of options, Boeing offered a 737C (Convertible) model in both -100 and -200 lengths. This model featured a 134 in × 87 in (340 cm × 221 cm) freight door just behind the cockpit, and a strengthened floor with rollers, which allowed for palletized cargo. A 737QC (Quick Change) version with palletized seating allowed for faster configuration changes between cargo and passenger flights.[75] With the improved short-field capabilities of the 737, Boeing offered the option on the -200 of the gravel kit, which enables this aircraft to operate on remote, unpaved runways.[76] Until retiring its -200 fleet in 2007, Alaska Airlines used this option for some of its combi aircraft rural operations in Alaska.[77] Northern Canadian operators Air Inuit, Air North, Canadian North, First Air and Nolinor Aviation still operate the gravel kit aircraft in Northern Canada, where gravel runways are common.

In 1988, the initial production run of the -200 model ended after producing 1,114 aircraft. The last one was delivered to Xiamen Airlines on August 8, 1988.[78][79]

737 Classic (second generation)

The Boeing 737 Classic is the name given to the -300/-400/-500 series of the Boeing 737 after the introduction of the -600/700/800/900 series:

The Classic series was originally introduced as the 'new generation' of the 737.[80] Produced from 1984 to 2000, 1,988 aircraft were delivered.[81] Development began in 1979 for the 737's first major revision. Boeing wanted to increase capacity and range, incorporating improvements to upgrade the aircraft to modern specifications, while also retaining commonality with previous 737 variants. In 1980, preliminary aircraft specifications of the variant, dubbed 737-300, were released at the Farnborough Airshow.[82]

737-300

Boeing engineer Mark Gregoire led a design team, which cooperated with CFM International to select, modify and deploy a new engine and nacelle that would make the 737-300 into a viable aircraft. They chose the CFM56-3B-1 high-bypass turbofan engine to power the aircraft, which yielded significant gains in fuel economy and a reduction in noise, but also posed an engineering challenge, given the low ground clearance of the 737 and the larger diameter of the engine over the original Pratt & Whitney engines. Gregoire's team and CFM solved the problem by reducing the size of the fan (which made the engine slightly less efficient than it had been forecast to be), placing the engine ahead of the wing, and by moving engine accessories to the sides of the engine pod, giving the engine a distinctive non-circular "hamster pouch" air intake.[48][83] Earlier customers for the CFM56 included the U.S. Air Force with its program to re-engine KC-135 tankers.[84]

The passenger capacity of the aircraft was increased to 149 by extending the fuselage around the wing by 9 feet 5 inches (2.87 m). The wing incorporated several changes for improved aerodynamics. The wingtip was extended 9 in (23 cm), and the wingspan by 1 ft 9 in (53 cm). The leading-edge slats and trailing-edge flaps were adjusted.[48] The tailfin was redesigned, the flight deck was improved with the optional EFIS (Electronic Flight Instrumentation System), and the passenger cabin incorporated improvements similar to those developed on the Boeing 757.[85] The prototype −300, the 1,001st 737 built, first flew on February 24, 1984 with pilot Jim McRoberts.[85] It and two production aircraft flew a nine-month-long certification program.[86]

737-400

In June 1986, Boeing announced the development of the 737-400,[87] which stretched the fuselage a further 10 ft (3.0 m), increasing the passenger load to 188.[88] The -400s first flight was on February 19, 1988, and, after a seven-month/500-hour flight-testing run, entered service with Piedmont Airlines that October.[89]

737-500

The -500 series was offered, due to customer demand, as a modern and direct replacement of the 737-200. It incorporated the improvements of the 737 Classic series, allowing longer routes with fewer passengers to be more economical than with the 737-300. The fuselage length of the -500 is 1 ft 7 in (48 cm) longer than the 737-200, accommodating up to 140[88] passengers. Both glass and older-style mechanical cockpits arrangements were available.[89] Using the CFM56-3 engine also gave a 25% increase in fuel efficiency over the older -200s P&W engines.[89]

The 737-500 was launched in 1987 by Southwest Airlines, with an order for 20 aircraft,[90] and flew for the first time on June 30, 1989.[89] A single prototype flew 375 hours for the certification process,[89] and on February 28, 1990, Southwest Airlines received the first delivery.[81]

After the introduction of the −600/700/800/900 series, the −300/400/500 series was called the 737 Classic series.[91]

The price of jet fuel reached a peak in 2008, when airlines devoted 40% of the retail price of an air ticket to pay for fuel, versus 15% in 2000.[92][93] Consequently, in that year carriers retired Classic 737 series aircraft to reduce fuel consumption; replacements consisted of more efficient Next Generation 737s or Airbus A320/A319/A318 series aircraft. On June 4, 2008, United Airlines announced it would retire all 94 of its Classic 737 aircraft (64 737-300 and 30 737-500 aircraft), replacing them with Airbus A320 jets taken from its Ted subsidiary, which has been shut down.[94][95][96]

737 NG (third generation)

The 737 Next Generation (NG) is the name given to the 737-600, 737-700/-700ER, 737-800, and 737-900/-900ER variants.

By the early 1990s, it had become clear that the new Airbus A320 was a serious threat to Boeing's market share, as Airbus won previously loyal 737 customers such as Lufthansa and United Airlines. In November 1993, Boeing's board of directors authorized the Next Generation program to upgrade the 737 Classic (−300/-400/-500) series. The third-generation derivative of the Boeing 737, the -600, -700, -800, and -900 series, were planned.[97] After engineering trade studies and discussions with major 737 customers, Boeing proceeded to launch the 737 Next Generation (NG) -600/700/800/900 series in late 1993.[1] It has been produced since 1996, introduced in 1997, and has updated CFM56-7s, a larger wing, an upgraded glass cockpit, and seat 108 to 215 passengers, with 6,996 built as of January 2019.[25]

The 737 Next Generation featured a redesigned wing with a wider wingspan and larger area, greater fuel capacity, and higher MTOWs. It was equipped with CFM56-7 series engines, a glass cockpit, and features upgraded and redesigned interior configurations. It has a longer range and larger variants than its predecessor. The series includes four main models, the −600, -700, -800, and -900, with seating for 108 to 215 passengers. The 737NG's primary competition is with the Airbus A320 family.

As of May 2019, a total of 7,097 737NG aircraft had been ordered, of which 7,031 have been delivered, the remaining orders are in the -700 BBJ, -800, -800 BBJ and -900ER variants.[1]

The 737NG variants were developed into additional versions such as the U.S. Navy's P-8 Poseidon.

737 MAX (fourth generation)

.jpg)

On July 20, 2011, Boeing announced plans for a fourth generation 737 series to be powered by the CFM International LEAP engine, with American Airlines intending to order 100 of these aircraft.[98] On August 30, 2011, Boeing confirmed the launch of the 737 new engine variant, to be called the Boeing 737 MAX.[99][100][101] The series competes with the Airbus A320neo family that was launched in December 2010 and reached 1,029 orders by June 2011, breaking Boeing's monopoly with American Airlines, which had an order for 130 A320neos that July.[102]

It is based on earlier 737 designs with more efficient LEAP-1B power plants, aerodynamic improvements (most notably split-tip winglets), and airframe modifications. It is offered in four main variants, typically offering 138 to 230 seats and a range of 3,215 to 3,825 nmi (5,954 to 7,084 km). The 737 MAX 7, MAX 8 (including the denser, 200-seat MAX 200), and MAX 9 replace the 737-700, -800, and -900 respectively. The further stretched 737 MAX 10 has also been added to the series.

The 737 MAX had its first flight on January 29, 2016, and gained FAA certification on March 8, 2017.[103][104] The first delivery was a MAX 8 on May 6, 2017 to Lion Air's subsidiary Malindo Air,[105] which put it into service on May 22, 2017.[106] As of January 2019, the series has received 5,011 firm orders.[1]

in March 2019, aviation authorities around the world grounded the 737 MAX following two hull loss crashes which caused 346 deaths.[107] On December 16, 2019, Boeing announced that it will suspend production of the 737 MAX from January 2020,[108] which was resumed in May 2020. In the midyear 2020, the FAA and Boeing conducted a series of recertification test flights.[109]

Other variants

Enhanced Short Runway Package

This short-field design package is an option on the 737-600, -700 and -800 and is standard equipment for the new 737-900ER. These enhanced short runway versions could increase pay or fuel loads when operating on runways under 5,000 feet (1,500 m). Landing payloads were increased by up to 8,000 lb on the 737-800 and 737-900ER and up to 4,000 lb on the 737-600 and 737-700. Takeoff payloads were increased by up to 2,000 lbs on the 737-800 and 737-900ER and up to 400 lbs on the 737-600 and 737-700. The package includes:[110]

- A winglet lift credit, achieved through additional winglet testing, that reduces the minimum landing-approach speeds.

- Takeoff performance improvements such as the use of sealed leading-edge slats on all takeoff flap positions, allowing the airplane to climb more rapidly on shorter runways.

- A reduced idle thrust transition delay between approach and ground-idle speeds, which improves stopping distances and increases field-length-limited landing weight

- Increased flight-spoiler deflection from 30o to 60o, improving aerodynamic braking on landing.

- A two-position tailskid at the rear of the aircraft to protect against inadvertent tailstrikes during landing, which allows higher aircraft approach attitudes and lower landing speeds.

The first enhanced version was delivered to Gol Transportes Aéreos (GOL) on July 31, 2006. At that time, twelve customers had ordered the package for more than 250 airframes. Customers include: GOL, Alaska Airlines, Air Europa, Air India, Egyptair, GE Commercial Aviation Services (GECAS), Hapagfly, Japan Airlines, Pegasus Airlines, Ryanair, Sky Airlines and Turkish Airlines.[111]

737 AEW&C

.jpg)

The Boeing 737 AEW&C is a 737-700IGW roughly similar to the 737-700ER. This is an Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C) version of the 737NG. Australia is the first customer (as Project Wedgetail), followed by Turkey and South Korea.

T-43/CT43A

The T-43 was a 737-200 modified for use by the United States Air Force for training navigators, now known as USAF combat systems officers. Informally referred to as the Gator (an abbreviation of "navigator") and "Flying Classroom", nineteen of these aircraft were delivered to the Air Training Command at Mather AFB, California during 1973 and 1974. Two additional aircraft were delivered to the Colorado Air National Guard at Buckley ANGB (later Buckley AFB) and Peterson AFB, Colorado, in direct support of cadet air navigation training at the nearby U.S. Air Force Academy.

Two T-43s were later converted to CT-43As, similar to the CT-40A Clipper below, in the early 1990s and transferred to Air Mobility Command and United States Air Forces in Europe, respectively, as executive transports. A third aircraft was also transferred to Air Force Material Command for use as a radar test bed aircraft and was redesignated as an NT-43A. The T-43 was retired by the Air Education and Training Command in 2010 after 37 years of service.[112]

C-40 Clipper

The Boeing C-40 Clipper is a military version of the 737-700C NG. It is used by both the United States Navy and the United States Air Force, and has been ordered by the United States Marine Corps.[113] Technically, only the Navy C-40A variant is named "Clipper", whereas the USAF C-40B/C variants are officially unnamed.

P-8 Poseidon

The P-8 Poseidon (formerly Multimission Maritime Aircraft) developed for the United States Navy by Boeing Defense, Space & Security, based on the Next Generation 737-800ERX.

The P-8 can be operated in the anti-submarine warfare (ASW), anti-surface warfare (ASUW), and shipping interdiction roles. It is armed with torpedoes, Harpoon anti-ship missiles and other weapons, and is able to drop and monitor sonobuoys, as well as operate in conjunction with other assets such as the Northrop Grumman MQ-4C Triton maritime surveillance unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV).

Boeing Business Jet (BBJ)

In the late 1980s, Boeing marketed the 77-33 jet, a business jet version of the 737-300.[114] The name was short-lived. After the introduction of the Next Generation series, Boeing introduced the Boeing Business Jet (BBJ) series. The BBJ1 was similar in dimensions to the 737-700 but had additional features, including stronger wings and landing gear from the 737-800, and had increased range over the other 737 models through the use of extra fuel tanks. The first BBJ rolled out on August 11, 1998 and flew for the first time on September 4.[115]

On October 11, 1999 Boeing launched the BBJ2. Based on the 737-800, it is 19 feet 2 inches (5.84 m) longer than the BBJ, with 25% more cabin space and twice the baggage space, but has slightly reduced range. It is also fitted with auxiliary belly fuel tanks and winglets. The first BBJ2 was delivered on February 28, 2001.[115]

Boeing's BBJ3 is based on the 737-900ER. The BBJ3 has 1,120 square feet (104 m2) of floor space, 35% more interior space, and 89% more luggage space than the BBJ2. It has an auxiliary fuel system, giving it a range of up to 4,725 nautical miles (8,751 km), and a Head-up display. Boeing completed the first example in August 2008. This aircraft's cabin is pressurized to a simulated 6,500-foot (2,000 m) altitude.[116][117]

Boeing Converted Freighter program

The Boeing Converted Freighter program (BCF), or the 737-800BCF program, was launched by Boeing in 2016. It converts old 737-800 passenger jets to dedicated freighters.[118] The first 737-800BCF was delivered in 2018 to GECAS, which is leased to West Atlantic.[119] Boeing has signed an agreement with Chinese YTO Cargo Airlines to provide the airline with 737-800BCFs pending a planned program launch.[120]

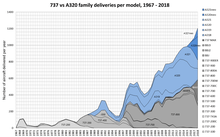

Competition

The Boeing 737 Classic, Next Generation and MAX series have faced significant competition from the Airbus A320 family first introduced in 1988. The relatively recent Airbus A220 family now also competes against the smaller capacity end of the 737 variants. The A320 was developed to compete also with the McDonnell Douglas MD-80/90 and 95 series; the 95 later becoming the Boeing 717.

From July 2017, Airbus had a 59.4% market share of the re-engined single aisle market, while Boeing had 40.6%; Boeing had doubts on over-ordered A320neos by new operators and expected to narrow the gap with replacements not already ordered.[121] However, in July 2017, Airbus had still 1,350 more A320neo orders than Boeing had for the 737 MAX.[122]

Boeing delivered 8,918 of the 737 family between March 1988 and December 2018,[123][124] while Airbus delivered 8,605 A320 family aircraft over a similar period since first delivery in early 1988.[125]

Operators

Civilian

The 737 is operated by more than 500 airlines, flying to 1,200 destinations in 190 countries: over 4,500 are in service and at any given time there are on average 1,250 airborne worldwide. On average, somewhere in the world, a 737 took off or landed every five seconds in 2006. Since entering service in 1968, the 737 has carried over 12 billion passengers over 74 billion miles (120 billion km; 65 billion nm), and has accumulated more than 296 million hours in the air. The 737 represents more than 25% of the worldwide fleet of large commercial jet airliners.[128][129]

Military

Many countries operate the 737 passenger, BBJ, and cargo variants in government or military applications.[130] Users with 737s include:

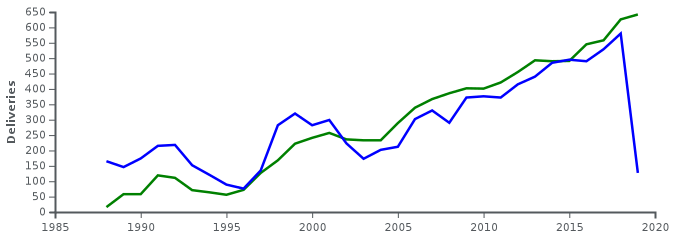

Orders and deliveries

Boeing delivered the 5,000th 737 to Southwest Airlines on February 13, 2006, the 6,000th 737 to Norwegian Air Shuttle in April 2009,[131] the 8,000th 737 to United Airlines on April 16, 2014.[132] The 10,000th 737 was ordered in July 2012,[133] and rolled out on March 13, 2018, as over 4,600 orders were pending.[134]

By 2006, there were an average of 1,250 Boeing 737s airborne at any given time, with two either departing or landing somewhere every five seconds.[128] The 737 was the most commonly flown aircraft in 2008,[135] 2009,[136] and 2010.[137]

In 2016, there were 6,512 737 airliners in service (5,567 737NGs plus 945 737-200s and 737 Classics), more than the 6,510 A320 family.[138] In 2017, there were 6,858 737 airliners in service (5,968 737NGs plus 890 737-200s and classics),[139] less than the 6,965 A320 family.[140]

The 737 had the highest, cumulative orders for any airliner until surpassed by the A320 family in October 2019.[141] As of February 2020, 15,115 units of the Boeing 737 of all series had been ordered, with 4,540 units to be delivered, or 4,351 when including "additional criteria for recognizing contracted backlog with customers beyond the existence of a firm contract".[142]

| Year | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deliveries | 8[lower-alpha 1] | 127 | 580 | 529 | 490 | 495 | 485 | 440 | 415 | 372 | 376 | 372 | 290 | 330 |

| 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 | 1990 | 1989 | 1988 | 1987 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 302 | 212 | 202 | 173 | 223 | 299 | 282 | 320 | 282 | 135 | 76 | 89 | 121 | 152 | 218 | 215 | 174 | 146 | 165 | 161 |

| 1986 | 1985 | 1984 | 1983 | 1982 | 1981 | 1980 | 1979 | 1978 | 1977 | 1976 | 1975 | 1974 | 1973 | 1972 | 1971 | 1970 | 1969 | 1968 | 1967 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 141 | 115 | 67 | 82 | 95 | 108 | 92 | 77 | 40 | 25 | 41 | 51 | 55 | 23 | 22 | 29 | 37 | 114 | 105 | 4 |

- Note that the 2020 deliveries consist of NG-based variants and include no 737 MAXs.

| Generation | Model series | ICAO code[143] | Orders | Deliveries | Unfilled orders | First flight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 737 Original | 737-100 | B731 | 30 | 30 | — | April 9, 1967 |

| 737-200 | B732 | 991 | 991 | — | August 8, 1967 | |

| 737-200C | 104 | 104 | — | September 18, 1968 | ||

| 737-T43A | 19 | 19 | — | March 10, 1973 | ||

| 737 Classic | 737-300 | B733 | 1,113 | 1,113 | — | February 24, 1984 |

| 737-400 | B734 | 486 | 486 | — | February 19, 1988 | |

| 737-500 | B735 | 389 | 389 | — | June 30, 1989 | |

| 737 NG | 737-600 | B736 | 69 | 69 | — | January 22, 1998 |

| 737-700 | B737 | 1,128 | 1,128 | — | February 9, 1997 | |

| 737-700C | 22 | 22 | — | April 14, 2000[144] | ||

| 737-700W | 17 | 14 | 3 | May 20, 2004[145] | ||

| 737-800 | B738 | 4,991 | 4,989 | 2 | July 31, 1997 | |

| 737-800A | 175 | 133 | 42 | April 25, 2009[146] | ||

| 737-900 | B739 | 52 | 52 | — | August 3, 2000 | |

| 737-900ER | 505 | 505 | — | September 1, 2006 | ||

| 737 BBJ | 737-BBJ1 (-700) | B737 | 121 | 121 | — | September 4, 1998 |

| 737-BBJ2 (-800) | B738 | 23 | 21 | 2 | N/A | |

| 737-BBJ3 (-900) | B739 | 7 | 7 | — | N/A | |

| 737 MAX | 737 MAX (-7,-8,-9,-10) | B37M / B38M / B39M / B3XM | 4,516 | 387 | 4,129 | January 29, 2016[147] |

In 2019, 737 orders dropped by 90%, as 737 MAX orders dried up after the March grounding.[148] The 737 MAX backlog fell by 182, mainly due to the Jet Airways bankruptcy, a drop in Boeing's airliner backlog was a first in at least the past 30 years.[149]

Accidents and incidents

As of February 2020, there has been a total of 481 aviation accidents and incidents involving all 737 aircraft,[150] including 214 hull losses resulting in a total of 5,565 fatalities.[151][152]

A Boeing analysis of commercial jet airplane accidents between 1959 and 2013 found that the hull loss rate for the Original series was 1.75 per million departures, for the Classic series 0.54, and the Next Generation series 0.27.[153]

During the 1990s, a series of rudder issues on series -200 and -300 aircraft resulted in multiple incidents. In two total loss accidents, United Airlines Flight 585 (a -200 series) and USAir Flight 427, (a -300), the pilots lost control of the aircraft following a sudden and unexpected deflection of the rudder, killing everyone aboard, a total of 157 people.[154] Similar rudder issues led to a temporary loss of control on at least five other 737 flights before the problem was ultimately identified. The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the accidents and incidents were the result of a design flaw that could result in an uncommanded movement of the aircraft's rudder.[155]:13[156]:ix As a result of the NTSB's findings, the Federal Aviation Administration ordered that the rudder servo valves be replaced on all 737s and mandated new training protocols for pilots to handle an unexpected movement of control surfaces.[157]

Following the crashes of two 737 MAX 8 aircraft, Lion Air Flight 610 in October 2018 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 in March 2019, which caused 346 deaths, national aviation authorities around the world grounded the 737 MAX series.[107] On December 16, 2019, Boeing announced that it would suspend production of the 737 MAX from January 2020.[108]

Aircraft on display

.jpg)

Owing to the 737's long production history and popularity, many older 737s have found use in museums after reaching the end of useful service.

- 19437/1: 737-130 registered N515NA on static display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. It was the first 737 built and is painted in NASA markings.[158]

- 19047/14: 737-222 registered N9009U preserved by Southern Illinois University Carbondale at Southern Illinois Airport.[159]

- 20213/160: 737-201 registered N213US forward fuselage on static display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington in USAir livery.[160]

- 20561/292: 737-281 registered LV-WTX on static display at the National Museum of Aeronautics in Morón, Buenos Aires.[161]

- 20562/293: 737-281 registered CC-CSK fuselage preserved at Motel Bahía in Concón, Chile.[162][163]

- 21262/470: 737-2H4 registered C-GWJT on static display at the British Columbia Institute of Technology Aerospace Technology Campus in Richmond, British Columbia. It is used for ground instructional training. The aircraft was donated by WestJet and bears its livery.[164][165]

- 21340/499: 737-2H4 registered N29SW on static display at the Kansas Aviation Museum in Wichita, Kansas. It was formerly operated by Ryan International Airlines and prior to that Southwest Airlines.[166][167]

- 21712/557: 737-275 registered C-GIPW preserved in operational condition at Alberta Flying Heritage Museum in Villeneuve, Alberta. Painted in Pacific Western Airlines livery.[168]

- 22578/767: 737-290C registered N740AS on static display at the Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum in Anchorage, Alaska. It was formerly operated by Alaska Airlines.[169]

- 22826/878: 737-2H4 registered YV1361 preserved at a hotel in Santiago, Chile. It was formerly operated by Avior Airlines.[170]

- 23059/980: 737-2Z6 registered 22-222 on static display at the Royal Thai Air Force Museum in Bangkok.[171][172]

- 22940/1037: 737-3H4 registered N300SW on static display at the Frontiers of Flight Museum in Dallas, Texas. It was the first such aircraft delivered to Southwest Airlines in November 1984.[173]

- 23257/1124: 737-301 registered PK-AWU on static display at ITE College Central in Singapore.[174]

- 23472/1194: 737-219 registered ZS-SMD on static display at the South African Airways Museum in Germiston, Gauteng.[175]

- 23660/1294: 737-377 registered G-CELS on static display at Norwich Airport (UK) as an Aviation Academy trainer. It is painted in the silver & red Jet2.com colour scheme, without the logo branding.[176]

- 27286/2528: 737-3Q8 registered N759BA on static display at the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona. It is painted in China Southern Airlines markings, and was previously operated by the airline as B-2921.[177]

Specifications

| Variant | 737-100 | 737-200 | 737-300/-400/-500 | 737-600/-700/-800/-900 | 737 MAX-7/8/9/10[179][180] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew | Two | |||||

| 2-class seats | 85 : 12F 73Y | 102 : 14F@38" 88Y@34" | 126/147/110 | 108/128/160/177 | 138/162/178/188 | |

| 1-class seats | 103@34" - 118@30" | 115@34" - 130@30" | 140+/159-168/122-132 | 123-130/140+/175+/177-215 | 153/178/193/204 | |

| Exit limit | 124 | 136 | 149/188/145 | 149/149/189/220 | 172/210/220/230 | |

| Length | 94 ft (29 m) | 100 ft 2 in (30.53 m) | 102–120 ft (31–37 m) | 102–138 ft (31–42 m) | 116.7–143.7 ft (35.56–43.8 m) | |

| Span | 93 ft (28 m) | 94 ft 9 in (28.88 m) | 112 ft 7 in (34.32 m) winglets: 117 ft 5 in (35.79 m) |

117 ft 10 in (35.92 m) | ||

| Wing[181] | 979.9 sq ft (91.04 m2), 25° sweep | 1,341.2 sq ft (124.60 m2) | 1,370 sq ft (127 m2)[182] | |||

| Height | 37 ft (11 m) | 36 ft 6 in (11.13 m) | 41 ft (12 m) | 40 ft 4 in (12.29 m) | ||

| Width | Fuselage: 148 inches (3.8 m), Cabin: 139.2 inches (3.54 m) | |||||

| Cargo | 650 cu ft (18 m3) | 875 cu ft (24.8 m3) | 882–1,373 cu ft 25.0–38.9 m3 |

720–1,826 cu ft 20.4–51.7 m3 |

1,543–1,814 cu ft 43.7–51.4 m3 | |

| MTOW | 110,000 lb (50,000 kg) | 128,100 lb (58,100 kg) | 133,500–150,000 lb 60,600–68,000 kg |

144,500–187,700 lb 65,500–85,100 kg |

177,000–194,700 lb 80,300–88,300 kg | |

| OEW | 62,000 lb (28,000 kg) | 65,300 lb (29,600 kg) | 70,440–76,760 lb 31,950–34,820 kg |

80,200–98,495 lb 36,378–44,677 kg |

MAX 8: 99,360 lb 45,070 kg[183] | |

| Fuel capacity | 4,720US gal / 17,865L | 5,970US gal / 22,596L[lower-alpha 1] | 5,311USgal 20,100L |

6,875-7,837 US gal 26,022-29,666 L |

6,853 US gal 25,941 L | |

| Speed | Mach 0.745–Mach 0.82 (430–473 kn; 796–876 km/h) Cruise—MMO[182] | Mach 0.785 (453 kn; 838 km/h) Cruise | ||||

| Takeoff[lower-alpha 2] | 6,099 ft (1,859 m)[181] | 7,500–8,690 ft 2,290–2,650 m[184] |

6,161–7,598 ft 1,878–2,316 m[181] |

|||

| Range | 1,540 nmi (2,850 km)[185] | 2,600 nmi (4,800 km)[lower-alpha 3][186] | 2,060–2,375 nmi 3,815–4,398 km[184] |

2,935–3,010 nmi 5,436–5,575 km[187] |

3,300–3,850 nmi 6,110–7,130 km | |

| Ceiling[182] | 37,000 ft (11,300 m) | 41,000 ft (12,500 m) | ||||

| Engines (×2) | Pratt & Whitney JT8D-7/-9/-5/-17 | CFM56-3 series | CFM56-7 series | CFM LEAP-1B | ||

| Thrust (×2) | 14,000 lbf (62 kN)[185] | 14,500–16,400 lbf 64–73 kN[186] |

20,000–23,500 lbf 89–105 kN |

20,000–27,000 lbf 89–120 kN |

up to 29,300 lbf (130 kN) | |

- With 810 gal/3,065 L auxiliary fuel tank

- MTOW, Sea Level, International Standard Atmosphere

- 120 passengers

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

References

Citations

- "Boeing 737 Model Summary – Orders and Deliveries". Boeing.com. Boeing. January 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- "737 price raised". Aviation Week. January 22, 1968. p. 31.

- "Airliner price index". Flight International. August 10, 1972. p. 183.

- "Transport News: Boeing Plans Jet." The New York Times, July 17, 1964. Retrieved: February 26, 2008.

- Endres 2001, p. 122

- Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 12

- Stephen Trimble (April 7, 2017). "Half-century milestone marks 737's enduring appeal". FlightGlobal.

- Sutter 2006, pp. 76–78.

- Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 17

- "German Airline Buys 21 Boeing Short-Range Jets." The Washington Post, February 20, 1965. Retrieved: February 26, 2008.

- Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 13

- Olason, M.L. and Norton, D.A. "Aerodynamic Philosophy of the Boeing 737", AIAA paper 65-739, presented at the AIAA/RAeS/JSASS Aircraft Design and Technology Meeting, Los Angeles California, November 1965. Reprinted in the AIAA Journal of Aircraft, Vol.3 No.6, November/December 1966, pp.524-528.

- Shaw 1999, p. 6

- Wallace, J. "Boeing delivers its 5,000th 737." Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 13, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Redding & Yenne 1997, p. 182

- "Original 737 Comes Home to Celebrate 30th Anniversary". www.boeing.com. Boeing. May 2, 1997. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 20

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet A16WE." faa.gov. Retrieved: September 3, 2010.

- Redding & Yenne 1997, p. 183

- Williams, Scott (January 18, 2009). "CAT II – Category II – Approach". Aviation Glossary. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 120

- Endres 2001, p. 124

- "Boeing 737 History". ModernAirlines.com. July 29, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- Bowers 1989, p. 496

- Podsada, Janice (January 11, 2020). "Small local suppliers flying blind through 737 Max crisis". HeraldNet.com. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- Guy Norris (February 20, 2018). "Spirit of '67: How Boeing's 'Baby' Jetliner Fuselage Made Its Journey West". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- Shaw 1999, p. 16

- "Boeing sells Wichita plant". The Spokesman-Review. February 23, 2005. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- John W. McCurry. "Spirit of Expansion". siteselection.com. Site Selection Online. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- Jon Ostrower (August 12, 2013). "Spirit AeroSystems CEO Says Boeing Exploring Increasing 737 Production". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- "Boeing firms up 737 replacement studies by appointing team". Flight International. March 3, 2006. Archived from the original on October 22, 2007. Retrieved April 13, 2008 – via FlightGlobal.

- Hamilton, Scott (June 24, 2010). "737 decision may slip to 2011: Credit Suisse". Flight International. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2010 – via FlightGlobal.

- "Boeing plans to develop new airplane to replace 737 Max by 2030". Chicago Tribune. November 5, 2014. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014.

- Guy Norris and Jens Flottau (December 12, 2014). "Boeing Revisits Past In Hunt For 737/757 Successors". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- Michael Bruno (February 7, 2018). "Boeing: Still 'A Lot' To Be Decided On NMA". Aviation Week Network.

- "Boeing's NMA in doubt as airlines take fresh look at 737 Max & 757 replacement". The Air Current. October 28, 2019.

- Jon Hemmerdinger (January 23, 2020). "Boeing to take another 'clean sheet' to NMA with focus on pilots". flightglobal.

- "COCKPIT WINDOWS Next-Generation 737, Classic 737, 727, 707 Airplanes" (PDF). PPG Aerospace Transparencies. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "Boeing Next-Generation 737 Gets a Face-Lift". Boeing Media Room. Boeing. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- Wallace, James. "Aerospace Notebook: New Boeing 717 design is bound to lift quite a few eyebrows". seattlepi.com. Hearst Seattle Media, LLC. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 37

- Brady 2014, pp. 144–145.

- Dekkers, Daniel, et al. (Project 2A2H). [home.deds.nl/~hink07/Report.pdf "Analysis Landing Gear 737-500."] Hogeschool van Amsterdam. Aviation Studies. October 2008. Retrieved: August 20, 2011.

- Volkmann, Kelsey. "Boeing gets OK for new carbon brakes." St. Louis Business Journal via bizjournals.com. Retrieved: April 22, 2010.

- Wilhelm, Steve. "Mindful of rivals, Boeing keeps tinkering with its 737." Puget Sound Business Journal, August 8, 2008. Retrieved: January 21, 2011.

- "Boeing Commercial Aircraft - In-Flight Fuel Jettison Capability" (PDF). Boeing. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- Cheung, Humphrey. "Troubled American Airlines jet lands safely at LAX." tgdaily.com, September 2, 2008. Retrieved: August 20, 2011.

- Endres 2001, p. 128

- Ostrower, Jon (August 30, 2011). "Boeing designates 737 MAX family". Air Transport Intelligence. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- leehamcoeu (August 9, 2019). "Bjorn's Corner: Fly by steel or electrical wire, Part 3". Leeham News and Analysis. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- NTSB. "NTSB ID: SEA97IA219" (PDF). fss.aero.

- "Boeing's MAX, Southwest's 737". theflyingengineer. December 13, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Freitag, William; Schulze, Terry (2009). "Blended winglets improve performance" (PDF). Aero Magazine. pp. 9, 12. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- Faye, Robert; Laprete, Robert; Winter, Michael (2002). "Blended Winglets". Aero Magazine. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- "Split Scimitar Schedules". aviationpartnersboeing.com. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "Southwest flies first 737 with new 'split scimitar' winglets". Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "Design, Analysis and Multi-Objective Constrained Optimization of Multi-Winglets" (PDF). Florida International University. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Kingsley-Jones, Max. "Narrow margins: Airbus and Boeing face pressue with the A-320 and 737." flightglobal.com, October 27, 2009. Retrieved: June 23, 2010.

- "Check Out Boeing's Swanky New High-Tech Interior." businessinsider.com. Retrieved: November 1, 2011.

- "Continental first North American carrier to offer Boeing's new Sky Interior". Flightglobal. December 29, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- "Continental Airlines Is First North American Carrier to Fly With Boeing's New Sky Interior". ir.unitedcontinentalholdings.com. United Airlines. December 29, 2010. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- Airlines, Alaska. "Boeing 737-800 Aircraft Information | Alaska Airlines". Alaska Airlines. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- "MAS takes delivery of first 737-800 with Sky Interior". Flightglobal.com. November 1, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- "Wolkenlos in Seattle – an Bord des neuen Jets von TUIfly." podcastexperten, March 7, 2011. Retrieved: May 12, 2011.

- Shaw 1999, p. 8

- Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 21

- "737 Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning" (PDF). Boeing. May 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 41

- "About the 737 Family." The Boeing Company. Retrieved: December 20, 2007.

- "The Airplane That Never Sleeps". Boeing. July 15, 2002. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- Bowers 1989, pp. 498–499

- "Southwest Airlines Retires Last of Founding Aircraft; Employees Help Celebrate the Boeing 737-200's Final Flight". swamedia.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "World Airline Census 2018". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- Thisdell and Seymour Flight International 30 July –5 August 2019, p. 36.

- Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 19

- Boeing 737-2T2C/Adv "Boeing 737." airliners.net. Retrieved: February 10, 2008.

- Carey, Susan (April 13, 2007). "Arctic Eagles Bid Mud Hens Farewell At Alaska Airlines". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Sharpe & Shaw 2001, p. 23

- "737 Family." Boeing.com, January 5, 2008. Retrieved: April 12, 2008.

- Shaw 1999, p. 7

- Endres 2001, p. 129

- Endres 2001, p. 126

- Sweetman, Bill, All mouth, Air & Space, September 2014, p.14

- Garvin 1998, p. 137.

- Shaw 1999, p. 10

- Shaw 1999, pp. 12–13

- Redding & Yenne 1997, p. 185

- FAA Type Certificate Data Sheet A16WE (PDF) (Report). Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration.

- Shaw 1999, p. 14

- Shaw 1999, p. 40

- "Boeing: Boeing 737 Facts". Boeing. September 6, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- "To Save Fuel, Airlines Find No Speck Too Small." The New York Times, June 11, 2008.

- "Jet Fuel Price Development". IATA. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

- "UAL Cuts Could Be Omen." The Wall Street Journal, June 5, 2008, p. B3.

- David Grossman (June 29, 2000). "Why Ted's demise is a boost for business travelers". USA Today. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Airline Shares Gain Despite Losses." The Wall Street Journal, July 23, 2008, p. B3.

- "Next Generation 737 Program Milestones." The Boeing Company. Retrieved: January 22, 2008.

- "Boeing and American Airlines Agree on Order for up to 300 Airplanes" (Press release). Boeing. July 20, 2011.

- "Boeing Launches 737 New Engine Family with Commitments for 496 Airplanes from Five Airlines" (Press release). Boeing. August 30, 2011.

- "Boeing officially launches re-engined 737". Flightglobal. August 30, 2011.

- Guy Norris (August 30, 2011). "Boeing Board Gives Go-Ahead To Re-Engined 737". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on August 4, 2017.

- "American Orders 460 Narrow Jets from Boeing and Airbus". The New York Times. July 20, 2011.

- "Boeing's 737 MAX takes wing with new engines, high hopes". The Seattle Times. January 29, 2016.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet No. A16WE" (PDF). FAA. March 8, 2017.

- Stephen Trimble (May 16, 2017). "Boeing delivers first 737 Max". Flightglobal.

- Hashim Firdaus (May 22, 2017). "Malindo operates world's first 737 Max flight". FlightGlobal.

- Austen, Ian; Gebrekidan, Selam (March 13, 2019). "Trump Announces Ban of Boeing 737 Max Flights". The New York Times.

- "Boeing Statement Regarding 737 MAX Production" (Press release). Boeing. December 16, 2019.

- "FAA Updates on Boeing 737 MAX". www.faa.gov. July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- Swatton 2000, pp. 149–151.

- "Boeing Delivers First 737 with Enhanced Short Runway Package to GOL". Boeing. July 31, 2006. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- Michelle Tan. "Air Force bids farewell to T-43". Army Times Publishing Company.

- Reim, Garrett (December 5, 2018). "US Marine Corps looks to buy two C-40 executive transports". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on April 25, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019 – via Flightglobal.com.

- Endres 2001.

- "The Boeing 737-700/800 BBJ/BBJ2." airliners.net. Retrieved: February 3, 2008.

- "Boeing Business Jets Launches New Family Member". Boeing. October 16, 2006. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- "Boeing Completes First BBJ 3". www.wingsmagazine.com. Wings. August 14, 2008. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- "Boeing launches 737-800BCF programme". Flightglobal.com. February 24, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- "Boeing delivers first 737-800BCF to West Atlantic". Flightglobal.com. April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- "Boeing to launch 737 freighter conversion program". aviationanalysis.net

- "Boeing positioned to narrow market share gap". Leeham Co. September 22, 2016.

- Addison Schonland (July 10, 2017). "The Big Duopoly Race". Airinsight.

- "Boeing Orders & Deliveries". Boeing.com. Boeing Press Calculations. Archived from the original on December 31, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- "Orders and Deliveries search page". Boeing. December 31, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Orders & deliveries viewer". Airbus. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- "Historical Orders and Deliveries 1974–2009". Airbus S.A.S. January 2010. Archived from the original (Microsoft Excel) on December 23, 2010. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- "Historical Deliveries". Boeing. December 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- "The 737 Story: Little Wonder". flightglobal. February 7, 2006.

- "Boeing 737 Facts". boeing.com. Boeing. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- "Boeing looks to sell more 737-based military jets". SeattlePi. June 9, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Kingsley-Jones, Max (April 22, 2009). "6,000 and counting for Boeing's popular little twinjet". Flight International.

- "Boeing's 737 Turns 8,000: The Best-Selling Plane Ever Isn't Slowing". Bloomberg Business Week. April 16, 2014.

- "737 tops 10,000 orders". Boeing. July 12, 2012. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012.

- Max Kingsley-Jones (March 13, 2018). "How Boeing built 10,000 737s". Flightglobal.

- "Boeing airliner deliveries rise 11%". Chicago Tribune. January 4, 2008. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012.

Boeing's 737, the world's most widely flown aircraft

- O'Sullivan, Matt (January 2, 2009). "Boeing shelves plans for 737 replacement". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012.

the 737, the world's most widely flown aircraft

- Layne, Rachel (February 26, 2010). "Bombardier's Win May Prod Airbus, Boeing to Upgrade Engines". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on March 1, 2010.

the 737, the world’s most widely flown plane

- Dan Thisdell (August 8, 2016). "FlightGlobal airliner census reveals fleet developments".

- Dan Thisdell (August 14, 2017). "787 stars in annual airliner census". Archived from the original on August 27, 2019.

- "World Airliner census". FlightGlobal. August 2017.

- David Kaminski-Morrow (November 15, 2019). "A320's order total overtakes 737's as Max crisis persists". Flightglobal.

- "Commercial : Boeing Orders and Deliveries". Boeing.

- "DOC 8643 - Aircraft Type Designators". International Civil Aviation Organization.

- Brady 2017

- "Boeing Conducts Successful First Flight of Australia's 737 Airborne Early Warning & Control Aircraft". Boeing.mediaroom.com. May 20, 2004. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- "P-8A Poseidon" (PDF). Boeing.mediaroom.com. May 31, 2015.

- "Boeing Completes Successful 737 MAX First Flight". Boeing.mediaroom.com. January 29, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- Hawkins, Andrew J. (January 14, 2020). "Boeing had more cancellations than orders in 2019 as 737 Max crisis deepens". The Verge.

- LeBeau, Phil (January 14, 2020). "Boeing posts negative commercial airplane orders in 2019 for first time in decades". CNBC.

- "Boeing 737 incident occurrences". Aviation-Safety.net, January 5, 2020. Retrieved: January 8, 2020.

- "Boeing 737 Accident summary". Aviation-Safety.net. January 5, 2020. Retrieved: January 8, 2020.

- "Boeing 737 Accident Statistics." January 8, 2020. Retrieved: January 8, 2020.

- "Statistical Summary of Commercial Jet Airplane Accidents – Accident Rates by Airplane Type" (PDF). boeing.com. Boeing. August 2014. p. 19.

- "Report says Boeing 737 rudder problems linger". TimesDaily. September 12, 1999. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- Uncontrolled Descent and Collision With Terrain, United Airlines Flight 585, Boeing 737-200, N999UA, 4 Miles South of Colorado Springs Municipal Airport, Colorado Springs, Colorado, March 3, 1991 (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. March 27, 2001. NTSB/AAR-01-01. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Aircraft Accident Report - Uncontrolled Descent and Collision With Terrain, USAir Flight 427, Boeing 737-300, N513AU, Near Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, September 8, 1994 (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. March 24, 1999. NTSB/AAR-99-01. Retrieved July 10, 2016.

- "Boeing Model 737 Series Airplanes". www1.airweb.faa.gov. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- "Boeing 737-130". The Museum of Flight. The Museum of Flight. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "N9009U United Airlines Boeing 737-200". Planespotters.net. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- "N213US USAir Boeing 737-200". Planespotters.net. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- "Airframe Dossier - Boeing 737-281, c/n 20561, c/r LV-WTX". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "CC-CSK Aerolineas Del Sureste Boeing 737-200". Planespotters.net. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- "Trasladaron el Boeing 737-200 al motel en Concón (Actualizado con fotos)". ModoCharlie. December 24, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- "WestJet donates 737-200 aircraft to BCIT Aerospace". BCIT. October 1, 2003. Archived from the original on July 3, 2004. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "C-GWJT WestJet Boeing 737-200 - cn 21262 / 470". Planespotters.net. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "Boeing 737-200". Kansas Aviation Museum. June 11, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "N29SW Ryan International Airlines Boeing 737-200 - cn 21340 / 499". Planespotters.net. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "C-GIPW Air Canada Tango Boeing 737-200". Planespotters.net. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- "N740AS Alaska Airlines Boeing 737-200 - cn 22578 / 767". Planespotters.net. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "Boeing 737-2H4/Adv - Avior Airlines". Airliners.net. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- "ROYAL THAI AIR FORCE MUSEUM, DON MUEANG" (PDF). December 26, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "60201 Royal Thai Air Force Boeing 737-200 - cn 23059 / 980". Planespotters.net. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "Boeing 737-300". Frontiers of Flight Museum. Frontiers of Flight Museum. June 23, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "Boeing 737-301 - Institute of Technical Education - ITE". March 6, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- "Pukeko". SAA Museum Society. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "Civilian Aviation • Home to the Civil Aviation Enthusiast • View topic - G-CELS Boeing 737-300". www.civilianaviation.co.uk. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- "737-300". Pima Air & Space Museum. Pimaair.org. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "Boeing 737 Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning" (PDF). Boeing Commercial Airplanes. September 2013.

- "737 MAX". Boeing. Technical Specs.

- "737 MAX Airport Compatibility Brochure" (PDF). Boeing. June 2017.

- Butterworth-Heinemann (2001). "Civil jet aircraft design". Elsevier. Boeing Aircraft.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet No. A16WE" (PDF). FAA. February 15, 2018.

- "737 MAX Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning" (PDF). Boeing. August 2017.

- "737-300/-400/-500" (PDF). startup. Boeing. 2007.

- Gerard Frawley. "Boeing 737-100/200 Technical data & specifications". The International Directory of Civil Aircraft.

- "737-200" (PDF). Startup. Boeing. 2007.

- "Boeing revises "obsolete" performance assumptions". Flight Global. August 3, 2015.

Bibliography

- Anderson, David F.; Eberhardt, Scott (2009). Understanding Flight. Chicago: McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-162696-5.

- Brady, Chris (October 17, 2014). The Boeing 737 Technical Guide (Pocket Budget Version). Lulu Enterprises. ISBN 978-1-291-77318-7.

- Brady, Chris (2017). The Boeing 737 Technical Guide. Kingsley, Frodsham, Cheshire, UK: Tech Pilot Services. ISBN 978-1-4475-3273-6.

- Bowers, Peter M. (1989). Boeing Aircraft Since 1916. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-037-2.

- Endres, Günter (2001). The Illustrated Directory of Modern Commercial Aircraft. St. Paul, Minn.: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-1125-7.

- Garvin, Robert V. (1998). Starting Something Big: The Commercial Emergence of GE Aircraft Engines. Reston, VA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. ISBN 1-56347-289-9.

- Redding, Robert; Yenne, Bills (1997). Boeing: Planemaker to the World. Berkeley, Cal.: Thunder Bay Pres. ISBN 978-1-57145-045-6.

- Sharpe, Michael; Shaw, Robbie (2001). Boeing 737-100 and 200. St. Paul, Minn.: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-0991-9.

- Shaw, Robbie (1995). Boeing Jetliners. London: Osprey Aerospace. ISBN 978-1-85532-528-9.

- Shaw, Robbie (1999). Boeing 737-300 to -800. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-0699-4.

- Sutter, Joe (2006). 747: Creating the World's First Jumbo Jet and Other Adventures from a Life in Aviation. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-0-06-088242-6.

- Swatton, P. J. (2000). "Landing Speeds". Aircraft Performance Theory for Pilots. Blackwell Science. doi:10.1002/9780470693827.ch19. ISBN 978-0-470-69382-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Boeing 737. |

- 737 page on Boeing.com

- The 737 Story on FlightInternational.com

- "737-200" (PDF). Boeing. 2007.

.jpg)