Fez, Morocco

Fez or Fes (/fɛz/; Arabic: فاس, romanized: Fas, pronounced [faːs]; Berber: ⴼⴰⵙ, [faːs]; French: Fès, [fɛs]) is a city in northern inland Morocco and the capital of the Fès-Meknès administrative region. It is the second largest city in Morocco after Casablanca,[4] with a population of 1.22 million (2020). Located to the northeast of Atlas Mountains, Fez is situated at the crossroad of the important cities of all regions; 206 km (128 mi) from Tangier to the northwest, 246 km (153 mi) from Casablanca, 189 km (117 mi) from Rabat to the west, and 387 km (240 mi) from Marrakesh to the southwest which leads to the Trans-Saharan trade route. It is surrounded by the high grounds, and the old city is penetrated by the River of Fez flowing from the west to east.

Fez فاس Fas / ⴼⴰⵙ Fès | |

|---|---|

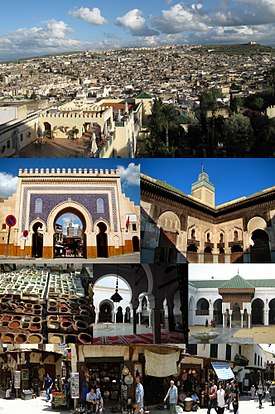

Clockwise from top: View of Fes el Bali, Bou Inania Madrasa, University of Al Quaraouiyine, street view, Zaouia Moulay Idriss II, Chouara Tannery, Bab Bou Jeloud | |

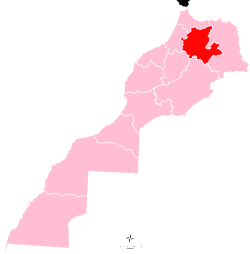

Fez Location of Fez within Morocco  Fez Fez (Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 34°02′36″N 05°00′12″W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Fès-Meknès |

| Founded | 789 |

| Founded by | Idrisid dynasty |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Idriss Azami Al Idrissi |

| • Governor | Said Zniber |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 320 km2 (120 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 410 m (1,350 ft) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| • City | 1,224,000 |

| • Rank | 2nd in Morocco |

| • Demonym | Fasi |

| Racial makeup | |

| • Arabs- Arabized Berbers | 53.6% |

| • Berbers | 32.7% |

| • Moriscos | 10.2% |

| • Others | 3.5% |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| Area code(s) | +212 (55) |

| Website | www.fes-city.com |

| Official name | Medina of Fez |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv |

| Designated | 1981 |

| Reference no. | [3] |

| State Party | Morocco |

| Region | Arab States |

Fez was founded under the Idrisid rule during the 8th-9th centuries C.E. It consisted of two autonomous and competing settlements. The migration of 2000 Arab families in the early 9th century gave the nascent city its Arabic character. After the downfall of the Idrisid dynasty, several empires came and went until the 11th century when the Almoravid Sultan Yusuf ibn Tashfin united the two settlements and rebuilt the city, which became today's Fes el Bali quarter. Under the Almoravid rule, the city gained a reputation for the religious scholarship and the mercantile activity.

Fez reached its zenith in the Marinid-era, regaining the status as the capital. Numerous madrasas, mosques, zawiyas and city gates were constructed which survived up until today. These buildings are considered the hallmarks of Moorish and Moroccan architectural styles. Marinid sultans also founded Fes Jdid quarter, where newer palaces and gardens were established. During this time, the Jewish population of the city grew as well, with the Mellah (Jewish quarter) attracting the Jewish migrants from other North African regions. After the overthrow of the Marinid dynasty, the city largely declined and was replaced by Marrakesh for political and cultural influence, but remained as the capital under the Wattasids and modern Morocco until 1912.

Today, the city largely consists of two old medina quarters, Fes el Bali and Fes Jdid, and modern urban area of Ville Nouvelle constructed during the French colonial era. The medina of Fez is listed as a World Heritage Site and is believed to be one of the world's largest urban pedestrian zones (car-free areas).[5] It has the University of Al Quaraouiyine which was founded in 859 and the oldest continuously functioning institute of higher education in the world. It also has Chouara Tannery from the 11th century, one of the oldest tanneries in the world. The city has been called the "Mecca of the West" and the "Athens of Africa," a nickname it shares with Cyrene in Libya.[6]

Etymology

Fez or Fas was derived from the Arabic word فأس Faʾs which means pickaxe, which legends say Idris I of Morocco used when he created the lines of the city. One noticeable thing was that the pickaxe was made from silver and gold.[7][8]

During the rule of the Idrisid dynasty, Fez consisted of two cities: Fas, founded by Idris I,[9] and al-ʿĀliyá, founded by his son, Idris II. During Idrisid rule the capital city was known as al-ʿĀliyá, with the name Fas being reserved for the separate site on the other side of the river; no Idrisid coins have been found with the name Fez, only al-ʿĀliyá and al-ʿĀliyá Madinat Idris. It is not known whether the name al-ʿĀliyá ever referred to both urban areas. It wasn't until 1070 that the two agglomerations were united and the name Fas was used for the combined site.[10]

History

Foundation and the Idrisids

The city was founded on a bank of the Jawhar river by Idris I in 789, founder of the Idrisid dynasty. His son, Idris II (808),[11] built a settlement on the opposing river bank. These settlements would soon develop into two walled and largely autonomous sites, often in conflict with one another: Madinat Fas and Al-'Aliya. In 808 Al-'Aliya replaced Walili as the capital of the Idrisids.

Arab emigration to Fez, including approximately 800 Andalusi families of mixed Arab and Iberian descent[12] in 817–818 expelled after a rebellion against the Umayyads of Córdoba, Andalusia, and 2000 Arab families banned from Kairouan (modern Tunisia) after another rebellion in 824, gave the city its Arabic character. The Andalusians settled in what was called the Fez, while the Tunisians found their home in al-'Aliya. These two waves of immigrants would subsequently give their name to the sites 'Adwat Al-Andalus and 'Adwat al-Qarawiyyin.[13] With the influx of Arabic-speaking Andalusians and Turnisians, the majority of the population was Arab, but rural Berbers from the surrounding countryside settled there throughout this early period, mainly in Madinat Fas (the Andalusian quarter) and later in Fes Jdid during the Marinid period.[14]

Upon the death of Idris II in 828, the dynasty's territory was divided among his sons. The eldest, Muhammad, received Fez. The newly fragmented Idrisid power would never again be reunified. During Yahya ibn Muhammad's rule in Fez the Kairouyine mosque, one of the oldest and largest in Africa, was built and its associated University of Al Quaraouiyine was founded (859).[15] Comparatively little is known about Idrisid Fez, owing to the lack of comprehensive historical narratives and that little has survived of the architecture and infrastructure of early Fez (Al-'Aliya). The sources that mention Idrisid Fez, describe a rather rural one, not having the cultural sophistication of the important cities of Al-Andalus and Ifriqiya.

In the 10th century, the city was contested by the Caliphate of Córdoba and the Fatimid Caliphate of Tunisia, who ruled the city through a host of Zenata clients. The Fatimids took the city in 927 and expelled the Idrissids, after which their Miknasa were installed there. The Miknasa were driven out of Fez in 980 by the Maghrawa, their fellow Zenata, allies of the Caliphate of Córdoba. It was in this period that the great Andalusian ruler Almanzor commissioned the Maghrawa to rebuild and refurnish the Al-Kairouan mosque, giving it much of its current appearance. According to the Rawd al-Qirtas and other Marinid era sources, the Maghrawi emir Dunas Al-Maghrawi filled up the open spaces between the two medinas and the banks of the river, dividing them with new constructions. Thus, the two cities grew into each other, being now only separated by their walls and the river. His sons fortified the city to a great extent. This could not keep the Almoravid emir Ibn Tashfin from conquering it in 1070, after more than a decade of battling the Zenata warriors in the area and constant besieging of the city.

In 1033, several thousand Jews were killed in the Fez Massacre.

Golden age and the Marinid period

Madinat Fas and Al-'Aliya were united in 1070 by the Almoravid dynasty: The walls dividing them were destroyed, bridges connecting them were built, and connecting walls were constructed that unified the medinas. Under Almoravid patronage the largest expansion and renovation of the Great Mosque of al-Qarawiyyin took place (1134-1143). Although the capital was moved to Marrakesh under the Almoravids, Fez acquired a reputation for Maliki legal scholarship and became an important centre of trade. Almoravid impact on the city's structure was such that the second Almoravid ruler, Yusuf ibn Tashfin, is often considered to be the second founder of Fez.[16]

Like many Moroccan cities, Fez was greatly enlarged during the Almohad Caliphate and saw its previously dominating rural aspect lessen. This was accomplished partly by the settling there of Andalusians and the further improvement of the infrastructure. At the start of the 13th century they broke down the Idrisid city walls and constructed new ones, which covered a much wider space. These Almohad walls exist to this day as the outline of Fes el Bali. Under Almohad rule the city grew to become one of the largest in the world between 1170 and 1180, with an estimated 200,000 people living there.[17]

In 1250 Fez regained its capital status under the Marinid dynasty. In 1276 after a massacre by the population to kill all Jews that was stopped by intervention of the Emir,[18] they founded Fes Jdid, which they made their administrative and military centre. Fez reached its golden age in the Marinid period, which marked the beginning of its official, historical narrative.[19][20] It is from the Marinid period that Fez's reputation as an important intellectual centre largely dates.[21] They established the first madrasas in the city and country.[22][23] The principal monuments in the medina, the residences and public buildings, date from the Marinid period.[24] The madrasas are a hallmark of Marinid architecture, with its striking blending of Andalusian and Almohad traditions. Between 1271 and 1357 seven madrassas were built in Fez, the style of which has come to be typical of Fassi architecture.

Ibn Battuta described the city of Fa's, which he passed through on his way to Sijilmasa.[25]

The Jewish quarter of Fez, the Mellah was built in 1438, near the royal residence in Fez Jdid. The Mellah at first consisted of Jews from Fez el Bali and soon saw the arrival of Berber Jews from the Atlas range and Jewish immigrants from al-Andalus. The Marinids spread the influence Idris I and encouraged Malikism, financing sharifian families as a way some say to legitimize their rule: In the 14th century, hundreds of families throughout Morocco tried to claim descent from Idris I, especially in Fez and the Rif mountains. In this regard, the Alaouite Sultan of Morocco, Moulay Ismail, established a syndicate responsible of verifying, through thorough historical, genealogical and scientific evidence, Moroccan families' sharifian ancestries of Idrissi and Alaouite descent which is still operating to this day under the official name in Arabic of (الرابطة الوطنية للشرفاء الأدارسة وأبناء عمومتهم بالمغرب), their official website is the following: chorafae.com. The 1465 Moroccan revolt in 1465 overthrew the last Maranid sultan. In 1474 the Marinids were replaced by their relatives of the Wattasid dynasty, who faithfully (but for a large part unsuccessfully) continued Marinid policies.[26]

Modern period

After the fall of the Marinids, the city remained the capital of Morocco under the Wattasids. However, in the 16th century, the Saadis, based in Marrakech, would attempt to overthrow the Wattasids. In the meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire came close to Fez after the conquest of Oujda in the 16th century. In January 1549 the Saadi sultan Mohammed ash-Sheikh took Fez and ousted the last Wattasid sultan Ali Abu Hassun. They later retook the city in 1553 with Ottoman support. However, this reconquest was short-lived, and in 1554 the Wattasids were decisively defeated in the battle of Tadla by the Saadis. The Ottomans would try to invade Morocco after the assassination of Mohammed ash-Sheikh in 1558, but were defeated by his son Abdallah al-Ghalib at the battle of Wadi al-Laban north of Fez. Hence, Morocco remained the only North-African state to deter and defeat the Ottomans.[27]

After the death of Abdallah al-Ghalib a new power struggle would emerge, after Abd al-Malik would take Fez with Ottoman support and oust his nephew Abu Abdullah. The latter would flee to Portugal where he asked king Sebastian of Portugal for help to regain his throne. This would lead to the Battle of Alcacer Quibir where Abd al-Malik's army would defeat the invading Portuguese army with the support of his Ottoman allies, ensuring Moroccan independence. Abd al-Malik himself also died during the battle and would be succeeded by Ahmad al-Mansur.

After the fall of the Saadi dynasty (1649), Fez was a major trading post of the Barbary Coast of North Africa. Until the 19th century it was the only source of fezzes (also known as the tarboosh). Then manufacturing began in France and Turkey as well. Originally, the dye for the hats came from a berry that was grown outside the city, known as the Turkish kızılcık or Greek akenia (Cornus mas). Fez was also the end of a north–south gold trading route from Timbuktu. Fez was a prime manufacturing location for embroidery and leather goods such as the Adarga.

The city became independent in 1790, under the leadership of Yazid (1790–1792) and later of Abu´r-Rabi Sulayman. In 1795 control of the city returned to Morocco. Fez took part in a rebellion in 1819–1821, led by Ibrahim ibn Yazid, as well as in the 1832 rebellion led by Muhammad ibn Tayyib.

The Tijani Sufi order, started by Ahmad al-Tijani (d. 1815), had its spiritual center in Fes. The order spread quickly among the literary elite of North West Africa, and its ulama, or theologians, had significant religious, intellectual, and political influence in Fes and beyond.[28]

Fes played a central role in the Hafidhiya, the brief civil war that erupted when Sultan Abd al-Hafid challenged his heavily Europe-allied brotherAbdelaziz for the throne.[29]

The French Colonel Charles Émile Moinier arrived in Fes March 15, 1908 at the head of the 4e Zouaves, an infantry unit composed of Tunisian troupes coloniales. Moinier established himself in Fes to protect Sultan Abd al-Hafid from threats, including the pretension of Ahmed al-Hiba, son of Ma al-'Aynayn, to the sultanate.[30][31]

.jpg)

Following the implementation of the Treaty of Fes, the city was heavily damaged in the 1912 Intifada of Fes and belonged to French Morocco until 1956.[32]

Fez was the capital of Morocco until 1912. Rabat then remained the capital even after Morocco achieved independence in 1955.

Despite its traditional character, there is a modern section: the "New City". Today it is a bustling commercial center.

Place Lalla Yeddouna at the heart of the Medina is currently undergoing reconstruction and preservation measures following a design competition sponsored by the Millennium Challenge Corporation (Washington D.C.)[33] and the Government of the Morocco. The construction projects scheduled for completion in 2016 encompass historic preservation of particular buildings, construction of new buildings that fit into the existing urban fabric and regeneration of the riverfront. The intention is to not only preserve the quality and characteristics of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, but to encourage the development of the area as a sustainable, mixed-use area for artisanal industries and local residents.

Climate

Located by the Atlas Mountains, Fez has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa) with a strong continental influence, shifting from relatively cool and wet in the winter to dry and hot days in the summer months between June and September. Rainfall can reach up to 800 mm (31 in) in good years. The winter highs typically reach around 15 °C (59 °F) in December–January. Frost is not uncommon during the winter period. The highest and lowest temperatures ever recorded in the city are 46.7 °C (116 °F) and −8.2 °C (17 °F), respectively.(see weather-table below). Fez's climate is strongly similar to that of Seville and Córdoba, Andalusia, Spain. Snowfall on average occurs once every 3 to 5 years. Fez recorded snowfall in three straight years in 2005, 2006 and 2007.[34][35][36][37]

| Climate data for Fez | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.0 (77.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

37.0 (98.6) |

40.8 (105.4) |

44.0 (111.2) |

46.7 (116.1) |

44.4 (111.9) |

41.7 (107.1) |

37.5 (99.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

46.7 (116.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.8 (92.8) |

30.4 (86.7) |

24.7 (76.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.4 (48.9) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

18.1 (64.6) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) |

5.0 (41.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.2 (17.2) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.9 (40.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.9 (42.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 72.2 (2.84) |

100.4 (3.95) |

93.6 (3.69) |

87.7 (3.45) |

53.0 (2.09) |

24.4 (0.96) |

3.0 (0.12) |

3.6 (0.14) |

17.0 (0.67) |

62.3 (2.45) |

89.1 (3.51) |

85.2 (3.35) |

691.5 (27.22) |

| Average rainy days | 12.1 | 13.2 | 13.5 | 13.5 | 10.2 | 5.3 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 4.7 | 9.1 | 12.7 | 12.1 | 109.8 |

| Average snowy days | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 60 | 55 | 58 | 62 | 64 | 71 | 79 | 77 | 75 | 64 | 60 | 60 | 65 |

| Source 1: Hong Kong Observatory[38] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meoweather.com,[37] Voodoo skies for extremes[36] Weather Atlas [39] NOAA [40] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Fez | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6.8 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [39] | |||||||||||||

Subdivisions

The prefecture is divided administratively into the following:[41]

| Name | Geographic code | Type | Households | Population (2004) | Foreign population | Moroccan population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agdal | 231.01.01. | Arrondissement | 32740 | 144064 | 747 | 143317 | |

| Mechouar Fes Jdid | 231.01.03. | Municipality | 6097 | 26078 | 83 | 25995 | |

| Saiss | 231.01.05. | Arrondissement | 32990 | 156590 | 561 | 156029 | |

| Fes-Medina | 231.01.07. | Arrondissement | 20088 | 91473 | 110 | 91363 | |

| Jnan El Ouard | 231.01.09. | Arrondissement | 32618 | 174226 | 15 | 174211 | |

| El Mariniyine | 231.01.11. | Arrondissement | 37958 | 163291 | 40 | 163251 | |

| Oulad Tayeb | 231.81.01. | Rural commune | 3233 | 19144 | 3 | 19141 | 5056 residents live in the center, called Ouled Tayeb; 14088 residents live in rural areas. |

| Ain Bida | 231.81.03. | Rural commune | 1146 | 6854 | 0 | 6854 | |

| Sidi Harazem | 231.81.05. | Rural commune | 982 | 5133 | 0 | 5133 | 3317 residents live in the center, called Skhinate; 1816 residents live in rural areas. |

Landmarks

Medina of Fez

The historic city of Fez consists of Fes el-Bali, the original city founded by the Idrisid dynasty on both shores of the Oued Fes (River of Fez) in the late 8th and early 9th centuries, and the smaller Fez el-Jdid, founded on higher ground to the west in the 13th century. It is distinct from Fez's now much larger Ville Nouvelle (new city) originally founded by the French. Fes el-Bali is the site of the famous Qarawiyyin University and the Mausoleum of Moulay Idris II, the most important religious and cultural sites, while Fez el-Jdid is the site of the enormous Royal Palace, still used by the King of Morocco today. These two historic cities are linked together and are usually referred to together as the "medina" of Fez, though this term is sometimes applied more restrictively to Fes el-Bali only.[lower-alpha 1] Fez is becoming an increasingly popular tourist destination and many non-Moroccans are now restoring traditional houses (riads and dars) as second homes in the medina. Fez is also considered the cultural and spiritual capital of Morocco.[42] In 1981, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) proclaimed Medina of Fez a World Cultural Heritage site, as "[they] include a considerable number of religious, civil and military monuments that brought about a multi-cultural society. This architecture is characterised by construction techniques and decoration developed over a period of more than ten centuries, and where local knowledge and skills are interwoven with diverse outside inspiration (Andalusian, Oriental and African). The Medina of Fez is considered as one of the most extensive and best conserved historic towns of the Arab-Muslim world."[43]

Places of worship

.jpg)

There are numerous historic mosques in the medina, some of which are part of a madrasa or zawiya. Among the oldest mosques still standing today are the highly prestigious Mosque of al-Qarawiyyin, founded in 857 (and subsequently expanded),[44] the Mosque of the Andalusians founded in 859–860,[45] the Bou Jeloud Mosque from the late 12th century[46], and possibly the Mosque of the Kasbah en-Nouar (which may have existed in the Almohad period but was likely rebuilt much later[42][47]). The very oldest mosques of the city, dating back to its first years, were the Mosque of the Sharifs (or Shurafa Mosque) and the Mosque of the Sheikhs (or al-Anouar Mosque); however, they no longer exist in their original form. The Mosque of the Sharifs was the burial site of Idris II and evolved into the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II that exists today, while the al-Anouar Mosque has left only minor remnants.[47] A number of mosques from the important Marinid era, when Fes el-Jdid was created to be the capital of Morocco, include the Great Mosque of Fez el-Jdid from 1276, the Abu al-Hassan Mosque from 1341,[48] the Chrabliyine Mosque from 1342,[49] the al-Hamra Mosque from around the same period (exact date unconfirmed),[50] and the Bab Guissa Mosque, also from the reign of Abu al-Hasan (1331-1351) but modified in later centuries.[51] Other major mosques from the more recent Alaouite period are the Moulay Abdallah Mosque, built in the early to mid-18th century with the tomb of Sultan Moulay Abdallah[50], and the R'cif Mosque, built in the reign of Moulay Slimane (1793-1822).[52] The Zawiya of Moulay Idriss II (previously mentioned) and the Zawiya of Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani include mosque areas as well, as do several other prominent zawiyas in the city.[42][47] Elsewhere, the Jewish quarter (Mellah) is the site of the 17th-century Ibn Danan Synagogue and multiple other synagogues, though none of them are functioning today.[53][54][55] The Ville Nouvelle (New City) also includes many modern mosques.

Madrasas

The city has traditionally retained the influential position as a religious capital in the region, exemplified by the Madrasa (or University) of al-Qarawiyyin which was established in 859 by Fatima al-Fihri originally as a mosque. The madrasa is the oldest existing and continually operating degree-awarding educational institution in the world according to UNESCO and Guinness World Records.[56][57] The Marinid dynasty (13th-15th century) devoted great attention to the construction of madrasas following the Maliki orthodoxy, resulting in the unprecedented prosperity of the city's religious institutions. The first madrasa built during the Marinid era was the Saffarin Madrasa in Fes el Bali by Sultan Abu Yusuf in 1271.[58]:312 Sultan Abu al-Hassan was the most prolific patron of madrasa construction, completing the Al-Attarine, Mesbahiyya and Sahrij Madrasa in Fez alone, and several other madrasas as well in other cities such as Salé and Meknes. His son Abu Inan Faris built the famed Bou Inania Madrasa, and by the time of his death, every major city in the Marinid Empire had at least one madrasa.[59] The library of the Madrasa of al-Qarawiyyin was also established under Marinid rule around 1350, which stores a large selection of valuable manuscripts dating back to the medieval era.[42] The largest madrasa in the medina is Cherratine Madrasa commissioned by the Alaouite sultan Al-Rashid in 1670, which is the only major non-Marinid foundation besides the Madrasa of al-Qarawiyyin.[60]

Fortifications

City walls and gates

The entire medina of Fez was heavily fortified with crenelated walls with watchtowers and gates, a pattern of urban planning which can be seen in Salé and Chellah as well.[59] City walls were placed into the current positions during the 11th century, under the Almoravid rule. During this period, the two formerly divided cities known as Madinat Fas and al-'Aliya were united under a single enclosure. The Almoravid fortifications were later destroyed and then rebuilt by the Almohad dynasty in the 12th century, under Caliph Muhammad al-Nasir.[47] The oldest sections of the walls today thus date back to this time.[53] These fortifications were restored and maintained by the Marinid dynasty from the 12th to 16th centuries, along with the founding of the royal citadel-city of Fes el-Jdid.[61] Construction of the new city's gates and towers sometimes employed the labour of Christian prisoners of war.[59]

The gates of Fez, scattered along the circuit of walls, were guarded by the military detachments and shut at night.[59] Some of the main gates have existed, in different forms, since the earliest years of the city.[47] The oldest gates today, and historically the most important ones of the city, are Bab Mahrouk (in the west), Bab Guissa (in the northeast), and Bab Ftouh (in the southeast).[47][53] After the foundation of Fes Jdid by the Marinids in the 13th century, new walls and three new gates such as Bab Dekkakin, Bab Semmarine, and Bab al-Amer were established along its perimeter.[62][63] Later, in modern times, the gates became more ceremonial rather than defensive structures, as reflected by the 1913 construction of the decorative Bab Bou Jeloud gate at the western entrance of Fes el-Bali by the French colonial administration.[53]

Forts and kasbahs

Along with the city walls and gates, several forts were constructed along the defensive perimeters of the medina during the different time periods. The military watchtowers built in its early days during the Idrisid era were relatively small. However, the city rapidly developed as the military garrison center of the region during the Almoravid era, in which the military operations were commanded and carried out to other North African regions and Southern Europe to the north, and Senegal river to the south. Subsequently, it led to the construction of numerous forts, kasbahs, and towers for both garrison and defense. A "kasbah" in the context of Maghrebi region is the traditional military structure for fortification, military preparation, command and control. Some of them were occupied as well by citizens, certain tribal groups, and merchants. Throughout the history, 13 kasbahs were constructed surrounding the old city.[64] Among the most prominent among them is the Kasbah An-Nouar, located at the western or north-western tip of Fes el-Bali, which dates back to the Almohad era but was restored and repurposed under the Alaouites.[47] Today, it is an example of a kasbah serving as a residential district much like the rest of the medina, with its own neighborhood mosque. The Kasbah Bou Jeloud, which no longer exists as a kasbah today, was once the governor's residence and stood near Bab Bou Jeloud, south of the Kasbah an-Nouar.[47] It too had its own mosque, known as the Bou Jeloud Mosque. Other kasbahs include the Kasbah Tamdert, built by the Saadis near Bab Ftouh, and the Kasbah Cherarda, built by the Alaouite sultan Moulay al-Rashid just north of Fes Jdid.[53][47] Kasbah Dar Debibagh is one of the newest kasbahs, built in 1729 during the Alaouite era at 2 km from the city wall in a strategic position.[64][65] The Saadis also built a number of strong bastions in the late 16th century to assert their control over Fes, including notably the Borj Nord which is among the largest strictly military structures in the city and now refurbished as a military museum.[66] Its sister fort, Borj Sud, is located on the hills to the south of the city.[47]

Tanneries

Since the inception of the city, tanning industry has been continually operating in the same fashion as it did in the early centuries. Today, the tanning industry in the city is considered one of the main tourist attractions. There are three tanneries in the city, largest among them is Chouara Tannery near the Saffarin Madrasa along the river, built in the 11th century. The tanneries are packed with the round stone wells filled with dye or white liquids for softening the hides. The leather goods produced in the tanneries are exported around the world.[67][68][69] The two other major tanneries are the Sidi Moussa Tannery to the west of the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II and the Ain Azliten Tannery in the neighbourhood of the same name on the northern edge of Fes el-Bali.[47]:220

Tombs and mausoleums

Located in the heart of Fes el Bali, the Zawiya of Moulay Idriss II is a zawiya (a shrine and religious complex; also spelled zaouia), dedicated to and containing the tomb of Idris II (or Moulay Idris II when including his sharifian title) who is considered the main founder of the city of Fez.[70][71] Another well-known and important zawiya is the Zawiyia of Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani, which commemorates Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani, the founder of Tijaniyyah tariqa from the 18th century.[72] A number of zawiyas are scattered elsewhere across the city, many containing the tombs of important Sufi saints or scholars, such as the Zawiya of Sidi Abdelkader al-Fassi, the Zawiya of Sidi Ahmed esh-Shawi, and the Zawiya of Sidi Taoudi Ben Souda.[73]

The old city also has several major historic cemeteries which existed outside the main city gates, namely the cemeteries of Bab Ftouh (the most significant), Bab Mahrouk, and Bab Guissa. Some of these cemeteries include marabouts or domed structures containing the tombs of local Muslim saints (often considered Sufis). One of the most important ones is the Marabout of Sidi Harazem in the Bab Ftouh Cemetery.[47] To the north, near the Bab Guissa Cemetery, there are also the Marinid Tombs built during the 14th century as a necropolis for the Marinid sultans, ruined today but still a well-known landmark of the city.[53]

Gardens

The Jnane Sbile Garden was created as a royal park and garden in the 19th century by Sultan Moulay Hassan I (ruled 1873-1894) between Fes el-Jdid and Fes el-Bali.[53]:296[47]:100 Today it is the oldest garden of Fes.[74] Many bourgeois and aristocratic mansions were also accompanied by private gardens, especially in the southwestern part of Fes el-Bali, an area once known as al-'Uyun.[47] Other gardens also exist within the grounds of the historic royal palaces of the city, such as the Agdal and Lalla Mina Gardens in the Dar al-Makhzen or the gardens of the Dar al-Beida (originally attached to Dar Batha).[53][47][75]

Funduqs/foundouks (historic merchant buildings)

The old city of Fez includes more than a hundred funduqs or foundouks (traditional inns, or urban caravanserais). These were commercial structures which provided lodging for merchants and travelers or housed the workshops of artisans.[47]:318 They also frequently served as venues for other commercial activities such as markets and auctions.[47] One of the most famous is the Funduq al-Najjariyyin, which was built in the 18th century by Amin Adiyil to provide accommodation and storage for merchants and which now houses the Nejjarine Museum of Wooden Arts & Crafts.[76][75] Other major important examples include the Funduq Shamma'in (also spelled Foundouk Chemmaïne) and the Funduq Staouniyyin (or Funduq of the Tetouanis), both dating from the Marinid era or earlier, and the Funduq Sagha which is contemporary with the Funduq al-Najjariyyin.[47][51][77][78]

Historic palaces and residences

.jpg)

Many old private residences have also survived to this day, in various states of conservation. One type of house known, centered around an internal courtyard, is known as a riad.[53] Such private houses include the Dar al-Alami[79], the Dar Saada (now a restaurant), Dar 'Adiyil, Dar Belghazi, and others.[53] Larger and richer mansions, such as the Dar Mnebhi, Dar Moqri, and Palais Jamaï (Jamai Palace), have also been preserved.[53] Numerous palaces and riads are now utilized as hotels for the tourism industry. The Palais Jamai, for example, was converted into a luxury hotel in the early 20th century.[80][53] The lavish former mansion of the Glaoui clan, known as the Dar Glaoui, is partly open to visitors but still privately owned.[81]

As a former capital, the city contains several royal palaces as well. Dar Batha is a former palace completed by the Alaouite Sultan Moulay Abdelaziz (ruled 1894-1908) and turned into a museum in 1915 with around 6,000 pieces.[47][82] A large area of Fes el-Jdid is also taken up by the 80-hectare Royal Palace, or Dar al-Makhzen, whose new ornate gates (built in 1969-71) are renowned but whose grounds are not open to the public as they are still used by the King of Morocco when visiting the city.[75]

Education

Universities

The University of Al Quaraouiyine is the oldest continually-operating university in the world.[83] The al-Karaouine mosque was founded by Fatima al-Fihri in 859 with an associated school, or madrasa, which subsequently became one of the leading spiritual and educational centers of the historic Muslim world.[84] It became a state university in 1963, and remains an important institution of learning today.[85]

Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University is a public university that was founded in 1975 and has two primary campuses in the city (Dhar El Mehraz and Sais).

Transport

The city is served by Saïss Airport. It also has an ONCF train station with lines east to Oujda and west to Tangier and Casablanca.[86]

Sport

Fez has two football teams, MAS Fez (Fés Maghrebi) and Wydad de Fès (WAF). They both play in the Botola the highest tier of the Moroccan football system and play their home matches at the 45,000 seat Complexe Sportif de Fès stadium.

The MAS Fez basketball team competes in the Nationale 1, Morocco's top basketball division.

International relations

Twin towns — sister cities

Fez is twinned with:

.svg.png)

See also

Notes

- Medina is the Arabic word for "city", which in former French colonies in North Africa is also used to refer to the old part of a city, as the French largely generally built new cities (Ville Nouvelles) next to them and left the historic cities intact.

References

Footnotes

Citations

- "Fez, Kingdom of Morocco", Lat34North.com & Yahoo! Weather, 2009, webpages: L34-Fes Archived 2018-08-30 at the Wayback Machine and Yahoo-Fes-stats.

- Morocco 2014 Census

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Medina of Fez – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- "Note de présentation des premiers résultats du Recensement Général de la Population et de l'Habitat 2014" (in French). High Commission for Planning. 20 March 2015. p. 8. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Mother Nature Network, 7 car-free cities

- "History of Fes". Archived from the original on 2011-03-16. Retrieved 2010-12-23.

- Cities of the Middle-East and North-Africa A historical enceclopedia. Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley, pagina 151.

- The Travels of Ibn Battuta

- Bigon, Liora (2016-06-06). Place Names in Africa: Colonial Urban Legacies, Entangled Histories. Springer. p. 83. ISBN 9783319324852.

- "An architectural Investigation of Marinid and Watasid Fes" (PDF). Etheses.whiterose.ac.uk. p. 19. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Fes". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 3 Mar. 2007

- The Places Where Men Pray Together, p. 463, at Google Books p. 55

- A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period By Jamil Mir'i Abun-Nasr. p. 51.

- Realm of Saints, p. 9, at Google Books

- Merriam Webster's Collegiate Encyclopedia. p.574.

- The Almoravids and the Meanings of Jihad, p. 43, at Google Books (p.51)

- Morocco 2009, p. 252, at Google Books (p.252)

- Roudh el-Kartas: Histoire des souverains du Maghreb, p. 459, at Google Books

- "An architectural Investigation of Marinid and Watasid Fes" (PDF). Etheses.whiterose.ac.uk. p. 16. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "An architectural Investigation of Marinid and Watasid Fes" (PDF). Etheses.whiterose.ac.uk. p. 22. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 896, at Google Books (p. 605)

- The Berbers and the Islamic State, p. 91, at Google Books (p. 90)

- Islamic Art a Visual Culture, p. 121, at Google Books (p. 121)

- 'http://www.al-hakawati.net/english/Cities/fez.asp Archived 2013-06-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. p. 281. ISBN 9780330418799.

- "An architectural Investigation of Marinid and Watasid Fes" (PDF). Etheses.whiterose.ac.uk. p. 5. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "3. North Africa, 1504-1799. 2001. The Encyclopedia of World History". 19 December 2007. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Brigaglia, Andrea. "Sufi Revival and Islamic Literacy: Tijaniyya Writings in Twentieth-Century Nigeria". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9781139624695. OCLC 855022840.

- Le 4e régiment de marche de tirailleurs tunisiens au 1er janvier 1918. 19.. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Abun-Nasr, Jamil M.; Abun-Nasr, Abun-Nasr, Jamil Mirʻi (1987-08-20). A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521337670.

- H. Z(J. W.) Hirschberg (1981). A history of the Jews in North Africa: From the Ottoman conquests to the present time, edited by Eliezer Bashan and Robert Attal. BRILL. p. 318. ISBN 90-04-06295-5.

- "Morocco Compact - Millennium Challenge Corporation". Mcc.gov. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-11-18. Retrieved 2014-09-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Weather history for Fez, Figuig, Morocco : Fez average weather by month". Meoweather.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- "Climatological Information for Fez, Morocco". Hong Kong Observatory. 15 August 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- "Fes, Morocco - Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- "The normals data and climate variable descriptions are presented in these tables as provided by the WMO Member country" (TXT). Ftp.atdd.noaa.gov. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Recensement général de la population et de l'habitat de 2004" (PDF). Haut-commissariat au Plan, Lavieeco.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- Gaudio, Attilio (1982). Fès: Joyau de la civilisation islamique. Paris: Les Presses de l'Unesco: Nouvelles Éditions Latines. ISBN 2723301591.

- 170. UNESCO. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Jami' al-Qarawiyyin. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Jami' al-Andalusiyyin. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Terrasse, Henri (1964). "La mosquée almohade de Bou Jeloud à Fès". Al-Andalus. 29 (2): 355–363.

- Le Tourneau, Roger (1949). Fès avant le protectorat: étude économique et sociale d'une ville de l'occident musulman. Casablanca: Société Marocaine de Librairie et d'Édition.

- Abu al-Hassan Mosque. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Fez. Archnet. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- Touri, Abdelaziz; Benaboud, Mhammad; Boujibar El-Khatib, Naïma; Lakhdar, Kamal; Mezzine, Mohamed (2010). Le Maroc andalou : à la découverte d'un art de vivre (2 ed.). Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Royaume du Maroc & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-3902782311.

- Rasif Mosque. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Métalsi, Mohamed (2003). Fès: La ville essentielle. Paris: ACR Édition Internationale. ISBN 978-2867701528.

- Gilson Miller, Susan; Petruccioli, Attilio; Bertagnin, Mauro (2001). "Inscribing Minority Space in the Islamic City: The Jewish Quarter of Fez (1438-1912)". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 60 (3): 310–327. doi:10.2307/991758. JSTOR 991758.

- "Fez, Morocco Jewish History Tour". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2020-04-08.

- "Oldest higher-learning institution, oldest university". Guinnessworldrecords.com. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Medina of Fez". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- Kubisch, Natascha (2011). "Maghreb - Architecture" in Hattstein, Markus and Delius, Peter (eds.) Islam: Art and Architecture. h.f.ullmann.

- Penell, C.R. Morocco: From Empire to Independence; Oneworld Publications, Oct 1, 2013. pp.66-67.

- Shiratin Madrasa. Archnet. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- Fortifications of Fès. Archnet. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Meredith, Martin. (2014). Fortunes of Africa: A 5,000 Year History of Wealth, Greed and Endeavour. Simon and Schuster.

- Hakluyt Society, (1896). Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society, p.592.

- نفائس فاس العتيقة : بناء 13 قصبة لأغراض عسكرية. Assabah. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- Qasbah Dar Debibagh. 'Archnet Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- البرج الشمالي. Museum with no Frontiers. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Chouara Tannery. Archnet. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Why You Need to Visit Fez in 20 Photos. Bloomberg. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Aziza Chaouni: Hybrid Urban Sutures: Filling in the Gaps in the Medina of Fez." Archit 96 no. 1 (2007): 58-63.

- "Fes". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 3 Mar. 2007

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521337674.

- Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani Zawiya. Archnet. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Fès et sainteté, de la fondation à l’avènement du Protectorat (808-1912): Hagiographie, tradition spirituelle et héritage prophétique dans la ville de Mawlāy Idrīs. Rabat: Centre Jacques-Berque. 2014. ISBN 9791092046175.

- "Jnane Sbile or Bab Bou Jeloud garden in Fez". Morocco.FalkTime. 2018-07-09. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- Parker, Richard (1981). A practical guide to Islamic Monuments in Morocco. Charlottesville, VA: The Baraka Press.

- Funduq al-Najjariyyin. Archnet. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- "Fès: Les fondouks de la médina restaurés et labellisés". L'Economiste (in French). 2016-04-08. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- "Qantara - The al-Shammā'īn Funduq". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- "Alami House". Archnet. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- "Histoire du Maroc : Palais Jamai, Patrimoine universel. – Cabinet Consulting Expertise International" (in French). Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- "Palais Glaoui | Fez, Morocco Attractions". www.lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Mezzine, Mohamed. "Batha Palace". Discover Islamic Art, Museum With No Frontiers. Retrieved March 2020. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Guinness World Records, Oldest University

- UNESCO, World Heritage Listing for Medina of Fez.

- Larbi Arbaoui, Al Karaouin of Fez: The Oldest University in the World, Morocco World News, 2 October 2012.

- "::.. Oncf ..::". Oncf.ma. Archived from the original on 2009-02-28. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- "Sister cities of İzmir (1/7)". Izmir-yerelgundem21.org.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- "Acordos de Geminação". Cm-coimbra.pt (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- "Kraków - Miasta Partnerskie" [Kraków -Partnership Cities]. Miejska Platforma Internetowa Magiczny Kraków (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2013-07-02. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

Further reading

- Le Tourneau, Roger (1974) [1961]. Fez in the Age of the Marinides. Translated by Besse Clement. Oklahoma University. ISBN 0-8061-1198-4.

- Vigo, Julian (2006). "The Renovation of Fes' medina qdima and the (re)Creation of the Traditional". Writing the City, Transforming the City. New Delhi: Katha. pp. 44–58.

- "Place Lalla Yeddouna A Neighborhood in the Medina of Fez, Morocco: International open project competition in two phases". Announced in September 2010 in collaboration with the Union International des Architectes (UIA) and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), to renew the area and upgrade the living and working standards of the artisans in the medina. The approach of the project is probably one of the most ambitious for an Arab medina and therefore of exemplary character. The open international project was won by the London-based architecture practice Mossessian & Partners.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fes. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Fez. |

| Look up Fez in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Official government website of the city

- "Fez". Islamic Cultural Heritage Database. Istanbul: Organization of Islamic Cooperation, Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture. Archived from the original on 2013-04-27.

- ArchNet.org. "Fez". Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT School of Architecture and Planning. Archived from the original on 2013-10-06.

| Preceded by Aleppo |

Capital of Islamic Culture 2007 |

Succeeded by Alexandria, Djibouti, Lahore |

.jpg)