Dirham

Dirham, dirhem or dirhm (Arabic: درهم); (Amazigh: ⴰⴷⵔⵉⵎ, romanized: adreem, was and, in some cases, still is a unit of currency in several Arab states. It was formerly the related unit of mass (the Ottoman dram) in the Ottoman Empire and the Sasanian Empire. The name derives from the name of the ancient Greek currency, drachma.[1]

Unit of mass

The dirham was a unit of weight used across North Africa, the Middle East, and Persia, with varying values.

In the late Ottoman Empire (Ottoman Turkish درهم), the standard dirham was 3.207 g;[2] 400 dirhem equal one oka. The Ottoman dirham was based on the Sasanian drachm, which was itself based on the Roman dram/drachm.

In Egypt in 1895, it was equivalent to 47.661 troy grains (3.088 g).[3]

There is currently a movement within the Islamic world to revive the Dirham as a unit of mass for measuring silver, although the exact value is disputed (either 3 or 2.975 grams).[4]

History

The word "dirham" comes from drachma (δραχμή), the Greek coin.[1] The Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire controlled the Levant and traded with Arabia, circulating the coin there in pre-Islamic times and afterward. It was this currency which was initially adopted as an Persian word; then near the end of the 7th century the coin became an Islamic currency bearing the name of the sovereign and a religious verse. The "dirham" was the coin of the Persians. The Arabs tried to introduced their own coin however, due to the lack of trust of the currency the persian Dirham was kept as the currency [5]. The dirham was struck in many Mediterranean countries, including Al-Andalus (Moorish Spain) and the Byzantine Empire (miliaresion), and could be used as currency in Europe between the 10th and 12th centuries, notably in areas with Viking connections, such as Viking York[6] and Dublin.

Dirham in Jewish orthodox law

The dirham is frequently mentioned in Jewish orthodox law as a unit of weight used to measure various requirements in religious functions, such as the weight in silver specie pledged in Marriage Contracts (Ketubbah), the quantity of flour requiring the separation of the dough-portion, etc. Jewish physician and philosopher, Maimonides, uses the Egyptian dirham to approximate the quantity of flour for dough-portion, writing in Mishnah Eduyot 1:2: "...And I found the rate of the dough-portion in that measurement to be approximately five-hundred and twenty dirhams of wheat flour, while all these dirhams are the Egyptian [dirham]." This view is repeated by Maran's Shulhan Arukh (Hil. Hallah, Yoreh Deah § 324:3) in the name of the Tur. In Maimonides' commentary of the Mishnah (Eduyot 1:2, note 18), Rabbi Yosef Qafih explains that the weight of each Egyptian dirham was approximately 3.333 grams,[7] or what was the equivalent to 16 carob-grains[8] which, when taken together, the minimum weight of flour requiring the separation of the dough-portion comes to approx. 1 kilo and 733 grams. Rabbi Ovadiah Yosef, in his Sefer Halikhot ʿOlam (vol. 1, pp. 288–291),[9] makes use of a different standard for the Egyptian dirham, saying that it weighed approx. 3.0 grams, meaning the minimum requirement for separating the priest's portion is 1 kilo and 560 grams. Others (e.g. Rabbi Avraham Chaim Naeh) say the Egyptian dirham weighed approx. 3.205 grams,[10] which total weight for the requirement of separating the dough-portion comes to 1 kilo and 666 grams. Rabbi Shelomo Qorah (Chief Rabbi of Bnei Barak) writes that the traditional weight used in Yemen for each dirham weighed 3.36 grams,[11] making the total weight for the required separation of the dough-portion to be 1 kilo and 770.72 grams.

The word drachmon (Hebrew: דרכמון), used in some translations of Maimonides' commentary of the Mishnah, has in all places the same connotation as dirham.[12]

Modern-day currency

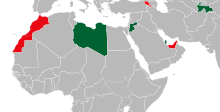

Currently the valid national currencies with the name dirham are :

- the Moroccan dirham

- the United Arab Emirates dirham

- the Armenian dram

Modern currencies with the subdivision dirham or diram are:

- 1 Libyan dinar is subdivided into 1,000 Dirham

- 1 Qatari riyal is subdivided into 100 Dirham

- 1 Jordanian dinar is subdivided into 10 Dirham

- 1 Tajikistani somoni is subdivided into 100 Diram

Also the unofficial modern gold dinar is divided into dirham.

See also

References

- Oxford English Dictionary, 1st edition, s.v. 'dirhem'

- based on an oka of 1.2828 kg; Diran Kélékian gives 3.21 g (Dictionnaire Turc-Français, Constantinople: Imprimerie Mihran, 1911) ; Γ. Μπαμπινιώτης gives 3.203 g (Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας, Athens, 1998)

- OED

- Ashtor, E. (October 1982). "Levantine weights and standard parcels: a contribution to the metrology of the later Middle Ages". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 45 (3): 471–488. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00041525. ISSN 0041-977X.

- BBC Art of Persia

- In addition to Islamic dirhams in ninth and tenth century English hoards, a counterfeit dirham was found at Coppergate, in York, struck as if for Isma'il ibn Achmad (ruling at Samarkand, 903-07/8), of copper covered by a once-silvery wash of tin (illustrated in Richard Hall, Viking Age Archaeology, [series Shire Archaeology] 2010:17, fig. 7).

- Mishnah - with a Commentary of Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, ed. Yosef Qafih, vol. 2 - Seder Neziqim, pub. Mossad Harav Kook: Jerusalem 1965, p. 189 (Hebrew title: משנה עם פירוש הרמב"ם)

- Mishnah - with a Commentary of Rabbi Moses ben Maimon (ed. Yosef Qafih), vol. 3, Mossad Harav Kook: Jerusalem 1967, s.v. Introduction to Tractate Menahoth, p. 68 (note 35) (Hebrew)

- Ovadiah Yosef, Sefer Halikhot ʿOlam, vol. 1, Jerusalem 2002 (Hebrew title: ספר הליכות עולם)

- Ovadiah Yosef, Sefer Halikhot ʿOlam, vol. 1, Jerusalem 2002, p. 288, sec. 11; Abraham Chaim Naeh, Sefer Kuntres ha-Shi'urim, Jerusalem 1943, p. 4 (Hebrew)

- Shelomo Qorah, ʿArikhat Shūlḥan - Yilqūṭ Ḥayyīm, vol. 13 (Principles of Instruction and Tradition), Benei Barak 2012, p. 206 (Hebrew title: עריכת שולחן - ילקוט חיים)

- Mishnah - with a Commentary of Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, ed. Yosef Qafih, vol. 3 - Seder Kodashim, pub. Mossad Harav Kook: Jerusalem 1967, s.v. Introduction to Tractate Menahoth, p. 68 (note 35) (Hebrew title: משנה עם פירוש הרמב"ם)