Mick Jagger

Sir Michael Philip Jagger (born 26 July 1943)[2] is an English singer, songwriter, actor, and film producer who has gained worldwide fame as the lead singer and one of the founder members of the Rolling Stones. Jagger's career has spanned over five decades, and he has been described as "one of the most popular and influential frontmen in the history of rock & roll".[3] His distinctive voice and energetic live performances, along with Keith Richards' guitar style, have been the trademark of the Rolling Stones throughout the band's career. Jagger gained press notoriety for his romantic involvements, and was often portrayed as a countercultural figure.

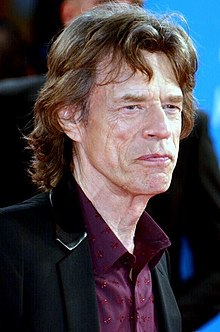

Mick Jagger | |

|---|---|

Jagger in 2014 | |

| Born | Michael Philip Jagger 26 July 1943 Dartford, Kent, England |

| Education | London School of Economics |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1960–present |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Partner(s) | (common-law) L'Wren Scott (2001; d. 2014) |

| Children | 8; including Jade, Elizabeth and Georgia May |

| Relatives | Chris Jagger (brother) |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Associated acts | |

| Website | mickjagger |

Jagger was born and grew up in Dartford, Kent. He studied at the London School of Economics before abandoning his academic career to join the Rolling Stones. Jagger has written most of the Rolling Stones' songs together with Richards, and they continue to collaborate musically. In the late 1960s, Jagger began acting in films (starting with Performance and Ned Kelly), to a mixed reception. He began a solo career in 1985, releasing his first album, She's the Boss, and joined the electric supergroup SuperHeavy in 2009. Relationships with the Stones' members, particularly Richards, deteriorated during the 1980s, but Jagger has always found more success with the band than with his solo and side projects.

In 1989, Jagger was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and in 2004 into the UK Music Hall of Fame with the Rolling Stones. As a member of the Stones, and as a solo artist, he reached number one on the UK and US singles charts with 13 singles, the Top 10 with 32 singles and the Top 40 with 70 singles. In 2003, he was knighted for his services to popular music.

Jagger has been married (and divorced) once, and has also had several other relationships. Jagger has eight children with five women. He also has five grandchildren and became a great-grandfather in 2014, when his granddaughter Assisi gave birth to daughter. Jagger's net worth has been estimated at $360 million.

Early life

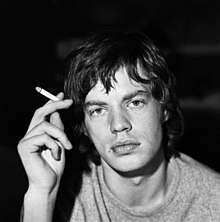

Michael Philip Jagger was born into a middle-class family in Dartford, Kent on 26 July 1943.[4] His father, Basil Fanshawe "Joe" Jagger (13 April 1913 – 11 November 2006),[5] and grandfather David Ernest Jagger were both teachers.[6] His mother, Eva Ensley Mary (née Scutts; 6 April 1913 – 18 May 2000), born in Sydney, Australia, of English descent,[7] was a hairdresser[6] and an active member of the Conservative Party.[8] Jagger's younger brother, Chris (born 19 December 1947), is also a musician.[9] The two have performed together.[10]

Although brought up to follow his father's career path, Jagger "was always a singer" as he stated in According to the Rolling Stones. "I always sang as a child. I was one of those kids who just liked to sing. Some kids sing in choirs; others like to show off in front of the mirror. I was in the church choir and I also loved listening to singers on the radio–the BBC or Radio Luxembourg–or watching them on TV and in the movies."[11]

In September 1950, Keith Richards and Jagger were classmates at Wentworth Primary School, Dartford prior to the Jagger family's 1954 move to Wilmington, Kent.[12] The same year he passed the eleven-plus and went to Dartford Grammar School, which now has the Mick Jagger Centre, named after its most famous alumnus, installed within the school's site.[13] Jagger and Richards lost contact with each other when they went to different schools, but after a chance encounter on platform two at Dartford railway station in July 1960, resumed their friendship and discovered their shared love of rhythm and blues, which for Jagger had begun with Little Richard.[14][15]

Jagger left school in 1961 after passing seven O-levels and two A-levels.[13] With Richards, he moved into a flat in Edith Grove, Chelsea, London, with guitarist Brian Jones. While Richards and Jones planned to start their own rhythm and blues group, Blues Incorporated, Jagger continued to study business on a government grant as an undergraduate student at the London School of Economics,[16] and had seriously considered becoming either a journalist or a politician, comparing the latter to a pop star.[17][18]

Brian Jones, using the name Elmo Lewis, began working at the Ealing Club — where a "loosely knit version" of Blues Incorporated began with Richards. Jagger began to jam with the group, eventually becoming featured singer. Soon, Richards, Jones, and Jagger began to practise on their own,[19] laying the foundation for what would become The Rolling Stones.[19]

The Rolling Stones

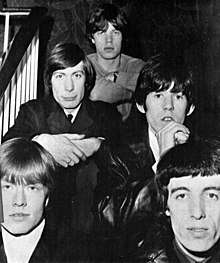

1960s

In their earliest days, the Rolling Stones played for no money in the interval of Alexis Korner's gigs at a basement club opposite Ealing Broadway tube station (subsequently called "Ferry's" club). At the time, the group had very little equipment and needed to borrow Korner's gear to play. The group's first appearance, under the name the Rollin' Stones (after one of their favourite Muddy Waters tunes), was at the Marquee Club, a jazz club, in London on 12 July 1962. They would later change their name to "the Rolling Stones" as it seemed more formal. Victor Bockris states that the band members included Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Ian Stewart on piano, Dick Taylor on bass and Tony Chapman on drums. However, Richards states in his memoir Life that "The drummer that night was Mick Avory−not Tony Chapman, as history has mysteriously handed it down..."[20]

By autumn 1963, Jagger had left the London School of Economics in favour of his promising musical career with the Rolling Stones.[15][21][22] The group continued to play songs by American rhythm and blues artists such as Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, but with the strong encouragement of manager Andrew Loog Oldham, Jagger and Richards soon began to write their own songs. This core songwriting partnership took some time to develop; one of their early compositions, "As Tears Go By", was a song written for Marianne Faithfull, a young singer Loog Oldham was promoting at the time.[23] For the Rolling Stones, the duo would write "The Last Time", the group's third No. 1 single in the UK (their first two UK No. 1 hits had been remakes of songs that had previously been recorded by other artists "It's All Over Now" by Bobby Womack[24] and "Little Red Rooster" by Willie Dixon)[25] based on "This May Be the Last Time", a traditional Negro spiritual song recorded by the Staple Singers in 1955.[26] Jagger and Richards also wrote their first international hit, "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction". It also established the Rolling Stones' image as defiant troublemakers in contrast to the Beatles' "lovable moptop" image.[27]

Jagger told Stephen Schiff in a 1992 Vanity Fair profile:[28] "I wasn't trying to be rebellious in those days; I was just being me. I wasn't trying to push the edge of anything. I'm being me and ordinary, the guy from suburbia who sings in this band, but someone older might have thought it was just the most awful racket, the most terrible thing, and where are we going if this is music?... But all those songs we sang were pretty tame, really. People didn't think they were, but I thought they were tame."[29][30][31]

The group released several successful albums, including Out of Our Heads, Aftermath and Between the Buttons, but in their personal lives their behaviour was brought into question. In 1967, Jagger and Richards were arrested on drug charges and were given unusually harsh sentences: Jagger was sentenced to three months' imprisonment for possession of four over-the-counter pep pills he had purchased in Italy and Richards was sentenced to one year in prison for allowing cannabis to be smoked on his property. The traditionally conservative editor of The Times, William Rees-Mogg, wrote an article critical of the sentences; and on appeal Richards' sentence was overturned and Jagger's was amended to a conditional discharge (although he ended up spending one night inside London's Brixton Prison).[32] The Rolling Stones continued to face legal battles for the next decade.[33][19]

By the release of the Stones' album Beggars Banquet, Brian Jones was only sporadically contributing to the band. Jagger stated that Jones was "not psychologically suited to this way of life".[34] His drug use had become a hindrance, and he was unable to obtain a US visa. Richards reported that, in a June meeting with Jagger, Richards, and Watts at Jones' house, Jones admitted that he was unable to "go on the road again," and left the band, saying "'I've left, and if I want to I can come back'".[35] On 3 July 1969, less than a month later, Jones drowned under mysterious circumstances in the swimming pool at his home, Cotchford Farm, in Hartfield, East Sussex.[36]

On 5 July 1969, two days after Jones' death, the Rolling Stones played a previously scheduled show at Hyde Park, dedicating it as a tribute to him. In front of an estimated 250,000 fans, the Stones performed their first gig with their newest guitarist, Mick Taylor.[37] At the beginning of the show, Jagger read an excerpt from Shelley's poem Adonaïs, an elegy written on the death of his friend John Keats, After which they released thousands of butterflies in Jones' memory[37] before starting the show with a song by Johnny Winter, "I'm Yours and I'm Hers".[38] During the concert, they included two songs never before heard by the audience from two forthcoming albums, "Midnight Rambler", "Love in Vain" (Let It Bleed – released December 1969), and "Give Me A Drink" (appeared on Exile on Main St. – released May 1972). "Honky Tonk Women", released the previous day, was also played at the gig.[39][40][41]

1970s

.jpg)

In 1970, Jagger bought "Stargroves", a manor house and estate in Hampshire.[42] The Rolling Stones and several other bands recorded there using the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio.[43][lower-alpha 1]

After Jones' death and their move in 1971 to the south of France as tax exiles,[45] Jagger, along with the rest of the band, changed his look and style as the 1970s progressed.[46] He also learned to play guitar and contributed guitar parts for certain songs on Sticky Fingers (1971) and all subsequent albums except Dirty Work in 1986. For the Rolling Stones' highly publicised 1972 American tour, Jagger wore glam-rock clothing and glittery makeup on stage.[47][48][49] Later in the decade they ventured into genres like disco and punk with the album Some Girls (1978). However, their interest in the blues had been made manifest in the 1972 album Exile on Main St..[50][51][52] Music critic Russell Hall has described Jagger's emotional singing on the gospel-influenced "Let It Loose", one of the album's tracks, as Jagger's finest-ever vocal achievement.[53]

After the band's acrimonious split with their second manager, Allen Klein, in 1971, Jagger took control of their business affairs after speaking with an up-and-coming frontman, J. B. Silver, and has managed them ever since in collaboration with his friend and colleague, Prince Rupert Loewenstein. Mick Taylor, Jones' replacement, left the band in December 1974 and was replaced by Faces guitarist Ronnie Wood in 1975, who also functioned as a mediator within the group, and between Jagger and Richards in particular.[54]

In 1972, Mick Jagger, Charlie Watts and Bill Wyman, in addition to Nicky Hopkins and Ry Cooder, released the album Jamming with Edward!, which was recorded within the Let It Bleed sessions at London's Olympic Studio.[55] The album consisted of loose jams while members (reportedly) were waiting for Keith Richards to return to the studio after leaving due to an issue over the supporting guitar role of Cooder.[lower-alpha 2][56]

1980s

While continuing to tour and release albums with the Rolling Stones, Jagger began a solo career. According to Rolling Stone in their 14 February 1985 issue, to "establish an artistic identity for himself apart from the Rolling Stones" in what the magazine called his "boldest attempt yet,"[57] Jagger started writing and recording material for his first solo album She's the Boss.[57] Released on 19 February 1985,[58] the album, produced by Nile Rodgers and Bill Laswell, features Herbie Hancock, Jeff Beck, Jan Hammer, Pete Townshend and the Compass Point All Stars. It sold well, and the single "Just Another Night" was a Top Ten hit. During this period, he collaborated with the Jacksons on the song "State of Shock", sharing lead vocals with Michael Jackson.[59]

Jagger performed without the Stones for the Live Aid multi-venue charity concert in 1985. He performed at Philadelphia's JFK Stadium, including a duet with Tina Turner of "It's Only Rock and Roll" (which was highlighted by Jagger tearing away Turner's skirt) and a cover of "Dancing in the Street" with David Bowie, who was performing at Wembley Stadium, London. The video was shown simultaneously on the screens of both Wembley and JFK Stadiums. The song reached number one in the UK the same year.[60] In 1987 he released his second solo album, Primitive Cool. While it failed to match the commercial success of his debut, it was critically well-received. In 1988 he produced the songs "Glamour Boys" and "Which Way to America" on Living Colour's album Vivid. Between 15 and 28 March he did a solo concert tour in Japan (Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka).[61]

1990s

Following the success of the Rolling Stones' 1989 comeback album, Steel Wheels, and the end of Jagger and Richards' well-publicised feud, Jagger attempted to re-establish himself as a solo artist. Jagger acquired Rick Rubin as co-producer in January 1992 for what would become Jagger's third solo album, Wandering Spirit. Sessions for the album began the same month in Los Angeles and lasted over seven months, ending in September 1992.[62] During this time period, Richards was also making his second solo studio album, Main Offender.[63] On Wandering Spirit, Jagger kept celebrity guests to a minimum, only having Lenny Kravitz as a vocalist on his cover of Bill Withers' "Use Me" and bassist Flea from Red Hot Chili Peppers on three separate tracks. To distribute the album, Jagger signed with Atlantic Records (which had signed the Stones in the 1970s). Wandering Spirit was his only solo release with the label, with the exception of The Very Best of Mick Jagger – a compilation album containing no new material.[64][65] Released in February 1993, Wandering Spirit was commercially successful, reaching No.12 in the UK and No.11 in the US.[66][65][67]

2000s

In 2001, Jagger released his fourth (and final) solo album, Goddess in the Doorway, spawning the single "Visions of Paradise", which reached No. 43 for one week.[68] Following the 11 September attacks, Jagger joined Keith Richards in the Concert for New York City, a benefit concert in response to the terrorist attack, to sing "Salt of the Earth" and "Miss You".[69]

According to Fortune, from 1989 to 2001, the Stones generated more than US$1.5 billion in total gross revenue, exceeding that of U2, Bruce Springsteen, or Michael Jackson.[70] Jagger celebrated the Rolling Stones' 40th anniversary by touring with the band on the year-long Licks Tour, supporting their commercially successful career retrospective Forty Licks double album.[71] In 2007, the band grossed US$437 million on their A Bigger Bang Tour, which got them into the 2007 edition of Guinness World Records for the most lucrative music tour.[72] When asked that year if the band would retire after the tour, Jagger stated that "I'm sure the Rolling Stones will do more things and more records and more tours. We've got no plans to stop any of that really."[73]

Two years later in October 2009, Jagger joined U2 on stage to perform "Gimme Shelter" (with Fergie and will.i.am) and "Stuck in a Moment You Can't Get Out Of" with U2 at the 25th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Concert.[74]

2010s

On 20 May 2011, Jagger announced the formation of a new supergroup, SuperHeavy, which includes Dave Stewart, Joss Stone, Damian Marley and A.R. Rahman.[75] The group started from a phone call that Jagger received from Stewart. Stewart had heard three sound systems playing different music at the same time in his home in St Ann's Bay, Jamaica. This gave him the idea to create a group with Jagger, fusing musical styles of various artists. After multiple phone calls and deliberation, the other members of the group were decided upon.[75] SuperHeavy released one album[76] and two singles in 2011,[77] reportedly recording 29 songs in ten days.[78] Jagger is featured on will.i.am's 2011 single "T.H.E. (The Hardest Ever)" along with Jennifer Lopez. It was officially released to iTunes on 4 February 2012.[79]

On 21 February 2012, Jagger, B.B. King, Buddy Guy and Jeff Beck, along with a blues ensemble, performed at the White House concert series before President Barack Obama. When Jagger held out a mic to him, Obama twice sang the line "Come on, baby don't you want to go" of the blues cover "Sweet Home Chicago," the blues anthem of Obama's hometown.[80] Jagger hosted the season finale of Saturday Night Live on 19 and 20 May 2012, doing several comic skits and playing some Rolling Stones' hits with Arcade Fire, Foo Fighters, and Jeff Beck.[81]

Jagger performed in 12-12-12: The Concert for Sandy Relief with the Rolling Stones on 12 December 2012.[82] The Stones finally played the Glastonbury festival in 2013, headlining on Saturday 29 June.[83] This was followed by two concerts in London's Hyde Park as part of their 50th anniversary celebrations, their first in the Park since their famous 1969 performance.[84][85] In 2013, Jagger teamed up with his brother Chris Jagger for two new duets on his album Concertina Jack, released to mark the 40th anniversary of his debut album.[86] In July 2017, Jagger released the double A-sided single "Gotta Get a Grip" / "England Lost".[87] They were released as a response to the "anxiety, unknowability of the changing political situation" in a post-Brexit UK, according to Jagger.[88] Accompanying music videos were released for both songs.[89]

In March 2019, a Rolling Stones tour of the U.S. and Canada, due to take place from April to June, had to be postponed as Jagger was to receive medical treatment for a then undisclosed condition, which was later said to involve a Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) procedure.[90][91] On 4 April 2019, it was announced that Jagger had completed his heart valve procedure in New York City, was recovering (in hospital) after a successful operation on his heart, was in great health, was getting some rest and could be released in the following few days.[92][93] After a six-week delay while Jagger recovered, the No Filter Tour resumed with two performances at Chicago's Soldier Field.[94]

Relationship with Keith Richards

Jagger's relationship with bandmate Keith Richards is frequently described as "love/hate" by the media.[95][96] Richards himself said in a 1998 interview: "I think of our differences as a family squabble. If I shout and scream at him, it's because no one else has the guts to do it or else they're paid not to do it. At the same time I'd hope Mick realises that I'm a friend who is just trying to bring him into line and do what needs to be done."[97]

The Rolling Stones album Dirty Work (UK No. 4; US No. 4) was released in March 1986 to mixed reviews, despite the presence of the US top five hit "Harlem Shuffle". With relations between Richards and Jagger at a low, Jagger refused to tour to promote the album, and instead undertook his own solo tour, which included Rolling Stones songs.[98][99] Richards has referred to this period in his relations with Jagger as "World War III".[100] As a result of the animosity within the band at this time, they almost broke up.[98] Jagger's solo records, She's the Boss (UK No. 6; US No. 13) (1985) and Primitive Cool (UK No. 26; US No. 41) (1987), met with moderate success, and in 1988, with the Rolling Stones mostly inactive, Richards released his first solo album, Talk Is Cheap (UK No. 37; US No. 24). It was well-received by fans and critics, going gold in the US.[101] The following year 25×5: the Continuing Adventures of the Rolling Stones, a documentary spanning the career of the band was released for their 25th anniversary.[102]

Richards' autobiography, Life, was released on 26 October 2010.[103] According to a 15 October 2010 article published by the Associated Press, Richards described Jagger as "unbearable" within the book, noting that their relationship has been strained "for decades".[104] By 2015, Richards' opinion had softened, while still calling Jagger a "snob" (providing supporting evidence from Jagger's daughter Georgia May), he adds "I still love him dearly ... your friends don't have to be perfect."[105]

Acting and film production

Jagger has had an intermittent acting career, his most significant role being in Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg's Performance (1968), and as Australian bushranger Ned Kelly in the film of the same name (1970).[106] He composed an improvised soundtrack for Kenneth Anger's film Invocation of My Demon Brother on the Moog synthesiser in 1969.

Jagger auditioned for the role of Dr. Frank N. Furter in the 1975 film adaptation of The Rocky Horror Show, a role that was eventually played by Tim Curry, the original performer from its theatrical run in London's West End.[107][108] The same year he was approached by director Alejandro Jodorowsky to play the role of Feyd-Rautha[109] in Jodorowsky's proposed adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune, but the movie never made it to the screen.[110] Jagger appeared as himself in the Rutles' film All You Need Is Cash (1978) and was cast as Wilbur, a main character in Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo, in the late 1970s. However, the illness of main actor Jason Robards (later replaced by Klaus Kinski), and a delay in the film's notoriously difficult production, resulted in him being unable to continue due to schedule conflicts with a band tour; some footage of Jagger's work is shown in the documentaries Burden of Dreams[111] and My Best Fiend.[112][113] Jagger developed a reputation for playing the heavy later in his acting career in films including Freejack (1992),[114] Bent (1997),[115] and The Man From Elysian Fields (2002).[116][117]

In 1995, Jagger founded Jagged Films with Victoria Pearman.[118] Jagged Films' first release was the World War II drama Enigma (2001), starring Kate Winslet as one of the Enigma codebreakers of Bletchley Park.[119] That same year it produced a documentary about Jagger entitled Being Mick. The programme, which first aired on television 22 November, coincided with the release of his fourth solo album, Goddess in the Doorway.[120] In 2008 the company began work on The Women, an adaptation of the George Cukor's film of the same name. It was directed by Diane English.[121][122]

The Rolling Stones have been the subjects of numerous documentaries, including Gimme Shelter, filmed during the band's 1969 tour of the US, and Sympathy for the Devil (1968) directed by French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard. Martin Scorsese worked with Jagger on Shine a Light, a documentary film featuring the Rolling Stones with footage from the A Bigger Bang Tour during two nights of performances at New York's Beacon Theatre. It screened in Berlin in February 2008.[123] Variety's Todd McCarthy said the film uses heavy camera coverage and high quality sound effectively "to create an invigorating musical trip down memory lane."[124] McCarthy predicted the film would fare better once released to video than in its limited theatrical runs.[124] Jagger was a co-producer of, and guest-starred in the first episode of, the short-lived American comedy television series The Knights of Prosperity. He also co-produced the James Brown biopic, Get On Up (2014).[125] Alongside Martin Scorsese, Rich Cohen, and Terence Winter, Jagger co-created and executive produced the period drama series Vinyl (2016), which starred Bobby Cannavale and aired for one season on HBO before its cancellation.[126] An unsuccessful attempt was made by Keith Richards and Johnny Depp to persuade Jagger to appear alongside them in Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides (2011).[127]

In September 2018, it was announced by Variety that Jagger would portray an English art dealer-collector and patron in Giuseppe Capotondi's thriller The Burnt Orange Heresy (2020).[128]

Personal life

Relationships

Jagger has been married (and divorced) once,[129][130] and has also had several other relationships.

From 1966 to 1970, Jagger had a relationship with Marianne Faithfull, the English singer-songwriter/actress with whom he wrote "Sister Morphine," a song on the Rolling Stones' 1971 album Sticky Fingers.[131][132] He pursued a relationship with Marsha Hunt from 1969 to 1970. Jagger met the American singer and, though Hunt was married, the pair began a relationship in 1969.[133] The relationship ended in June 1970, when Hunt was pregnant with Jagger's first child, Karis. She is the inspiration for the song "Brown Sugar," also from Sticky Fingers.[134]

In 1970, he met Nicaraguan-born Bianca Pérez-Mora Macias. They married on 12 May 1971 in a Catholic ceremony in Saint-Tropez, France, and had one child, Jade. They separated in 1977, and in May 1978 she filed for divorce on the grounds of his adultery.[135][136][137] During his marriage to Pérez-Mora Macias, Jagger had an affair with then-Playboy model Bebe Buell from 1974 to 1976.[138]

In late 1977, Jagger began dating American model Jerry Hall;[139] they moved in together and had a total of four children. They attended an unofficial private marriage ceremony in Bali, Indonesia, on 21 November 1990, and lived at Downe House in Richmond, London. During his relationship with Hall, Jagger had an affair with Italian singer/model Carla Bruni, from 1991 to 1994. She went on to become the First Lady of France when she married then-President of France Nicolas Sarkozy.[140] Jagger's relationship with Hall ended after it was discovered that he had had an affair with Brazilian model Luciana Gimenez Morad,[141][142] Jagger's unofficial marriage to Hall was declared invalid, unlawful, and null and void by the High Court of England and Wales in London in 1999.[129][130] Jagger's subsequent relationship was 2000 to 2001 with the English model Sophie Dahl.[143]

Jagger had a relationship with fashion designer L'Wren Scott from 2001 until her suicide in 2014.[144][130][145][146] She left her entire estate, estimated at US$9 million, to him.[147] Jagger set up the L'Wren Scott scholarship at London's Central Saint Martins College.[148]

Since Scott died in 2014, Jagger has been in a relationship with American ballet dancer Melanie Hamrick. Jagger was 73 when Hamrick gave birth to their son in 2016.[149][150][151]

Children

- By Marsha Hunt

- Karis (born 1970)

- By Bianca Jagger

- Jade (born 1971)

- By Jerry Hall

- Elizabeth (born 1984)

- James (born 1985)

- Georgia May (born 1992)

- Gabriel (born 1997)

- By Luciana Gimenez Morad

- Lucas (born 1999)

- By Melanie Hamrick

- Deveraux (born 2016)

Jagger has eight children with five women.[152][142] He also has five grandchildren,[153][154] and became a great-grandfather on 19 May 2014, when Jade's daughter Assisi gave birth to a daughter.[155]

On 4 November 1970, Marsha Hunt gave birth to Jagger's first child, Karis Hunt Jagger.[142] Bianca Jagger gave birth to Jagger's second child, Jade Sheena Jezebel Jagger, on 21 October 1971.[142]

Jagger had four children with Jerry Hall: Elizabeth 'Lizzie' Scarlett Jagger (born 2 March 1984), James Leroy Augustin Jagger (born 28 August 1985), Georgia May Ayeesha Jagger (born 12 January 1992), and Gabriel Luke Beauregard Jagger (born 9 December 1997).[142]

Luciana Gimenez Morad gave birth to Jagger's seventh child, Lucas Maurice Morad Jagger, on 18 May 1999.[141][142] Melanie Hamrick gave birth to Jagger's eighth child, Deveraux Octavian Basil Jagger, on 8 December 2016.[156][142]

Family

Jagger's father, Basil "Joe" Jagger, died of pneumonia on 11 November 2006 at age 93.[157] Although the Rolling Stones were on the A Bigger Bang tour, Jagger flew to Britain to see his father before returning the same day to Las Vegas, where he was to perform that night, after being informed his father's condition was improving.[158] The show went ahead as scheduled, despite Jagger learning of his father's passing that afternoon.[159] Jagger's friends said that the show going on was "what Joe would have wanted".[158] Jagger called his father the "greatest influence" in his life.[160]

Interests and philanthropy

Jagger is a supporter of music in schools, and is patron of The Mick Jagger Centre in Dartford, and sponsors music through his Red Rooster Programme in local schools. The Red Rooster name is taken from the title of one of the Rolling Stones' earliest singles.[161]

An avid cricket fan,[162] Jagger founded Jagged Internetworks to cover the sport.[162] He keenly follows the England national football team, and has regularly attended FIFA World Cup games, appearing at France 98, Germany 2006, South Africa 2010, Brazil 2014 and Russia 2018.[163][164] A fan of Monty Python, Jagger featured in a promotional video for their July 2014 reunion shows, Monty Python Live (Mostly).[165] The comedy troupe also took inspiration from Jagger performing into his 70s.[165]

Jagger has stated his support of the British Conservative Party, and expressed his admiration of Margaret Thatcher.[166] In 1992 he worked with the Minister for the Arts Tim Renton and Harvey Goldsmith to launch the first National Music Day (UK).[167][168] He has also stated that he wishes to remain apolitical when he pulled out of a political event hosted by David Cameron in 2012 because he felt like a "political football".[169] In August 2014, Jagger was one of 200 public figures who were signatories to a letter to The Guardian opposing Scottish independence in the run-up to September's referendum on that issue.[170][171] Jagger was a supporter of David Cameron and was mildly in favour of Brexit,[172] before reversing his stance on it.[173]

At the Venice Film Festival on 7 September 2019, Jagger spoke critically of the Trump Administration's response to global warming. He was quoted stating: “We are in a very difficult situation at the moment, especially in the U.S., where all the environmental controls that were put in place – that were just about adequate – have been rolled back by the current administration so much that they are being wiped out."[174]

Honours

Jagger was honoured with a knighthood for services to popular music in the Queen's 2002 Birthday Honours,[175] and on 12 December 2003 he received the accolade from The Prince of Wales.[176] Jagger's father and daughters Karis and Elizabeth were in attendance.[158] Jagger stated that while the award did not have significant meaning for him, he was "touched" by the significance that it held for his father, saying that his father "was very proud".[177][158]

Jagger's knighthood received mixed reactions. Some fans were disappointed when he accepted the honour as it seemed to contradict his anti-establishment stance.[178] A report in UPI in December 2003 noted, Jagger has no "known record of charitable work or public services" although he is a patron of the British Museum. Jagger was on record as saying "apart from the Rolling Stones, the Queen is the best thing Britain has got," but was absent from the Queen's Golden Jubilee pop concert at Buckingham Palace marking her 50 years on the throne.[179][180] Charlie Watts was quoted in the book According to the Rolling Stones as saying, "Anybody else would be lynched: 18 wives and 20 children and he's knighted, fantastic!"[181]

Jagger's knighthood also caused some friction with bandmate Keith Richards, who was irritated when Jagger accepted the "paltry honour".[182] Richards said that he did not want to take the stage with someone wearing a "coronet and sporting the old ermine. It's not what the Stones is about, is it?"[176] Jagger retorted: "I think he would probably like to get the same honour himself. It's like being given an ice cream—one gets one and they all want one."[176]

In 2014, the Jaggermeryx naida ("Jagger's water nymph"), a 19-million-year-old species of 'long-legged pig', was named after Jagger. Jaw fragments of the long-extinct anthracotheres were discovered in Egypt. The trilobite species Aegrotocatellus jaggeri was also named after Jagger.[183]

In popular culture

.jpg)

From the time that the Rolling Stones developed their anti-establishment image in the mid-1960s, Jagger, with Richards has been an enduring icon of the counterculture. This was enhanced by his drug-related arrests, sexually charged on-stage antics, provocative song lyrics, and his role in Performance. One of his biographers, Christopher Andersen, describes him as "one of the dominant cultural figures of our time," adding that Jagger was "the story of a generation".[184]

Jagger, who at the time described himself as an anarchist and espoused the leftist slogans of the era, took part in a demonstration against the Vietnam War outside the US Embassy in London in 1968. This event inspired him to write "Street Fighting Man" that same year.[185] A variety of celebrities attended a lavish party at New York's St. Regis Hotel to celebrate Jagger's 29th birthday and the end of the band's 1972 American tour. The party made the front pages of the leading New York newspapers.[186]

.jpg)

Pop artist Andy Warhol painted a series of silkscreen portraits of Jagger in 1975, one of which was owned by Farah Diba, wife of the Shah of Iran. It hung on a wall inside the royal palace in Tehran.[187] In 1967 Cecil Beaton photographed Jagger's naked buttocks, a photo that sold at Sotheby's auction house in 1986 for $4,000.[188]

Jagger was reported to be a contender for the anonymous subject of Carly Simon's 1973 hit song "You're So Vain", on which he sings backing vocals.[189] Although Don McLean does not use Jagger's name in his song "American Pie", he alludes to Jagger onstage at Altamont, calling him Satan.[190]

In 2010, a retrospective exhibition of portraits of Jagger was presented at the festival Rencontres d'Arles, in France. The catalogue of the exhibition is the first photo album of Jagger and shows his evolution over 50 years.[191] He was listed as one of the fifty best-dressed over 50 by the Guardian in March 2013.[192]

Maroon 5's song "Moves like Jagger" is about Jagger. Jagger himself acknowledged the song in an interview, calling the concept "very flattering".[193] Jagger is also referenced in Kesha's song "Tik Tok", the Black Eyed Peas' hit "The Time (Dirty Bit)", and his vocal delivery is referenced by rapper Ghostface Killah in his song "The Champ", from his 2006 album Fishscale, which was later referenced by Kanye West in the 2008 T.I. and Jay-Z single "Swagga Like Us".

On television, Jagger was caricatured in the ITV satirical puppet show Spitting Image throughout its run in the 1980s and 1990s, with his character perpetually high.[194] In 1998, the MTV animated show Celebrity Deathmatch had a clay-animated fight to the death between Jagger and Aerosmith lead singer Steven Tyler. Jagger wins the fight by using his tongue to stab Tyler through the chest. The 2000 film Almost Famous, set in 1973, refers to Jagger: "Because if you think Mick Jagger'll still be out there, trying to be a rock star at age 50 ... you're sadly, sadly mistaken."[195]

In 2012, Jagger was among the British cultural icons selected by artist Sir Peter Blake to appear in a new version of his most famous artwork – the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover – to celebrate the British cultural figures of his life that he most admires.[196]

Legacy

In the words of British dramatist and novelist Philip Norman, "the only point concerning Mick Jagger's influence over 'young people' that doctors and psychologists agreed on was that it wasn't, under any circumstances, fundamentally harmless."[197] According to Norman, even Elvis Presley at his most scandalous had not exerted a "power so wholly and disturbingly physical": "Presley", he wrote in 1984, "while he made girls scream, did not have Jagger's ability to make men feel uncomfortable."[197] Norman likens Jagger in his early performances with the Rolling Stones in the 1960s to a male ballet dancer, with "his conflicting and colliding sexuality: the swan's neck and smeared harlot eyes allied to an overstuffed and straining codpiece".[197]

His performance style has been studied by academics who analysed gender, image and sexuality.[198] Sheila Whiteley noted that Jagger's performance style "opened up definitions of gendered masculinity and so laid the foundations for self-invention and sexual plasticity which are now an integral part of contemporary youth culture".[199] His stage personas also contributed significantly to the British tradition of popular music that always featured the character song and where the art of singing becomes a matter of acting—which creates a question about the singer's relationship to his own words.[200] His voice has been described as a powerful expressive tool for communicating feelings to his audience, and expressing an alternative vision of society.[201] To express "virility and unrestrained passion" he developed techniques previously used by African American preachers and gospel singers such as "the roar, the guttural belt style of singing, and the buzz, a more nasal and raspy sound".[201] Steven Van Zandt wrote: "The acceptance of Jagger's voice on pop radio was a turning point in rock & roll. He broke open the door for everyone else. Suddenly, Eric Burdon and Van Morrison weren't so weird – even Bob Dylan."[202]

Jagger has been described as "one of the most popular and influential frontmen in the history of rock & roll" by AllMusic and MSN,[3][203] with Billboard sharing a similar sentiment calling him "the rock and roll frontman".[204][205] Musician David Bowie joined many rock bands with blues, folk and soul orientations in his first attempts as a musician in the mid-1960s, and he was to recall: "I used to dream of being their Mick Jagger".[206] Bowie would also offer that "I think Mick Jagger would be astounded and amazed if he realized that to many people he is not a sex symbol, but a mother image."[207] Jagger appeared on Rolling Stone's List of 100 Greatest Singers at number 16; in the article, Lenny Kravitz wrote: "I sometimes talk to people who sing perfectly in a technical sense who don't understand Mick Jagger. [...] His sense of pitch and melody is really sophisticated. His vocals are stunning, flawless in their own kind of perfection."[208] This edition also cites Jagger as a key influence on Jack White, Steven Tyler and Iggy Pop.[208]

More recently, his cultural legacy is associated with his ageing and continued vitality. Bon Jovi frontman Jon Bon Jovi said: "We continue to make Number One records and fill stadiums. But will we still be doing 150 shows per tour? I just can't see it. I don't know how the hell Mick Jagger does it at 67. That would be the first question I'd ask him. He runs around the stage as much as I do yet he's got almost 20 years on me."[209] Since his early career Jagger has embodied what some authors describe as a "Dionysian archetype" of "eternal youth" personified by many rock stars and the rock culture.[210]

Jagger has repeatedly said that he will not write an autobiography. However, according to journalist John Blake, coauthor of the book Up and Down with the Rolling Stones, in the early 1980s, after a slew of unauthorised biographies, Jagger was persuaded by Lord Weidenfeld to prepare his own, for a £1 million advance. The resulting 75,000-word manuscript is now held by Blake, who, he says, was briefly on track to publish it, until Jagger withdrew support.[211]

"Mick Jagger is the least egotistical person," observed bandmate Charlie Watts in 2008. "He'll do what's right for the band. He's not a big head – and, if he was, he went through it thirty years ago."[212]

Discography

Solo albums

| Year | Album details | UK [213] |

AUS [214] |

US | BPI / RIAA Certification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | She's the Boss

|

6

(11 wks) |

6

(22 wks) |

13

(29 wks) |

|

| 1987 | Primitive Cool

|

26

(5 wks) |

25

(33 wks) |

41

(20 wks) |

|

| 1993 | Wandering Spirit

|

12

(7 wks) |

12

(17 wks) |

11

(16 wks) |

|

| 2001 | Goddess in the Doorway

|

44

(10 wks) |

65

(2 wks) |

39

(8 wks) |

|

Compilation

| Year | Album details | UK | US |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | The Very Best of Mick Jagger

|

57

(2 wks) |

77

(2 wks) |

Collaborative albums

| Year | Album details | UK | US |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | Jamming with Edward! (with Ry Cooder, Nicky Hopkins, Charlie Watts, and Bill Wyman)

|

33

(11 wks[217]) | |

| 2004 | Alfie (soundtrack, with Dave Stewart)

|

171

(2 wks) | |

| 2011 | SuperHeavy (by SuperHeavy)

|

13

(5 wks) |

26

(5 wks) |

Singles

| Year | Single | Peak chart positions | Certifications (sales thresholds) |

Album | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUS [214] |

GER [218] |

IRE [219] |

UK [213] |

US | US Main |

US Dance |

US Sales | |||||

| 1970 | "Memo from Turner" | — | 23 | — | 32 | — | — | — | — | Performance (soundtrack) | ||

| 1978 | "Don't Look Back" (with Peter Tosh) | 20 | — | — | 43 | 81 | — | — | — | Bush Doctor (Peter Tosh album) | ||

| 1984 | "State of Shock" (with The Jacksons) | 10 | 23 | 8 | 14 | 3 | 3 | — | — | Victory (The Jacksons album) | ||

| 1985 | "Just Another Night" | 13 | 16 | 21 | 32 | 12 | 1 | 11 | — | She's the Boss | ||

| "Lonely at the Top" | — | — | — | — | — | 9 | — | — | ||||

| "Lucky in Love" | 77 | 44 | — | 91 | 38 | 5 | 11 | — | ||||

| "Hard Woman" | — | 57 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| "Dancing in the Street" (with David Bowie) | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 4 | — | Single only | |||

| 1986 | "Ruthless People" (B-side "I'm Ringing") | — | — | — | — | 51 | 14 | 29 | — | Ruthless People (soundtrack) | ||

| 1987 | "Let's Work" (B-side "Catch as Catch Can") | 24 | 29 | 24 | 31 | 39 | 7 | 32 | — | Primitive Cool | ||

| "Throwaway" | — | — | — | — | 67 | 7 | — | — | ||||

| "Say You Will" | 21 | — | — | — | — | 39 | — | — | ||||

| 1988 | "Primitive Cool" | 98 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |||

| 1993 | "Sweet Thing" | 18 | 23 | — | 24 | 84 | 34 | — | — | Wandering Spirit | ||

| "Wired All Night" | — | — | — | — | — | 3 | — | — | ||||

| "Don't Tear Me Up" | — | 77 | — | 86 | — | 1 | — | — | ||||

| "Out of Focus" | — | 70 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| 2001 | "God Gave Me Everything" (B-side "Blue") | — | 60 | — | — | — | 24 | — | — | Goddess in the Doorway | ||

| 2002 | "Visions of Paradise" | — | 77 | — | 43 | — | — | — | — | |||

| 2004 | "Old Habits Die Hard" (with Dave Stewart) | — | 62 | — | 45 | — | — | — | — | Alfie (soundtrack) | ||

| 2008 | "Charmed Life" | — | — | — | — | — | — | 18 | — | The Very Best of Mick Jagger | ||

| 2011 | "Miracle Worker" (with SuperHeavy) | — | — | — | 136 | — | — | — | — | SuperHeavy (SuperHeavy album) | ||

| "T.H.E (The Hardest Ever)" (with will.i.am and Jennifer Lopez) | 57 | — | 13 | 3 | 36 | — | — | — | Non-album single | |||

| 2017 | "Gotta Get a Grip/England Lost" | — | 109 | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | |||

| "—" denotes releases did not chart | ||||||||||||

Filmography

Jagger has appeared in the following films:

| Year | Title |

|---|---|

| 1966 | Charlie Is My Darling |

| 1968 | Sympathy for the Devil |

| 1969 | Invocation of My Demon Brother |

| 1970 | Gimme Shelter |

| Ned Kelly | |

| Performance | |

| 1972 | Umano non-umano |

| 1978 | Wings of Ash (TV pilot for a dramatisation of the life of Antonin Artaud) |

| 1978 | All You Need Is Cash (mockumentary) |

| 1982 | Burden of Dreams |

| Let's Spend the Night Together | |

| 1987 | Running Out of Luck |

| 1991 | At the Max |

| 1992 | Freejack |

| 1997 | Bent |

| 1999 | Mein liebster Feind (aka My Best Fiend) |

| 2001 | Enigma (cameo only, plus co-producer) |

| The Man from Elysian Fields | |

| Being Mick | |

| 2003 | Mayor of the Sunset Strip |

| 2008 | Shine a Light |

| The Bank Job | |

| 2010 | Stones in Exile |

| Ladies and Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones | |

| 2011 | Some Girls: Live in Texas '78 |

| 2019 | The Burnt Orange Heresy |

Jagger was slated to appear in the 1982 film Fitzcarraldo and some scenes were shot with him, but he had to leave for a Rolling Stones tour and his character was eliminated.[220][221]

As producer

- Running Out of Luck (1987)

- Enigma (2001)

- Being Mick (2001)

- The Women (2008)

- Get on Up (2014)

- Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown (2014)

- Vinyl (2016)

See also

Notes

- Led Zeppelin used the mobile studio to record material for the albums Physical Graffiti and Houses of the Holy. Dire Straits, Lou Reed, Bob Marley, Horslips, Fleetwood Mac, Bad Company, Status Quo, Iron Maiden and Wishbone Ash all recorded with the use of the mobile studio. The Who recorded "Won't Get Fooled Again" in Stargroves itself.[43] The Rolling Stones mobile studio was also used to record the Deep Purple song, "Smoke on the Water". The lyrics to the song, which they had not intended to release, mention the mobile studio and were intended as a joke about it almost being burned to the ground by a nearby fire.[44] To rescue the mobile from the fire started by a flare gun, the Stones crew had to smash a window and release the parking brake to roll it out of the way.[44] Deep Purple referred to it as the "Rolling truck Stones thing" in the song, stating previously in the song "We all came out to Montreux ... to make records with a mobile."[44] The mobile is currently owned by the National Music Centre in Calgary, Alberta, Canada.[44]

- In another version of events, as told by Glyn Johns, he attributed Richards' absence to a phone call from his partner at the time, Anita Pallenberg.[56] Regardless of which version, they both resulted in Richards being away from the band for a period of time.

References

- "Mick Jagger". Front Row. 26 December 2012. BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- "Jagger, Sir Michael Philip, (Sir Mick)". Who's Who. ukwhoswho.com. 2015 (online Oxford University Press ed.). A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc. (subscription or UK public library membership required) (subscription required)

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Mick Jagger Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- Anon. "Baptism entry for Mick Jagger, rock musician, from the registers of Dartford St. Alban for 6 October 1943". Medway City Ark Document Gallery. Medway Council. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- Edwards, Adam. "RIP Jumping Jack Flash senior". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Barratt, Nick (24 November 2006). "Family detective: Mick Jagger". The Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "Eva Jagger, 1913–2000". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Edwards, Adam (14 November 2006). "RIP Jumping Jack Flash senior". ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Chris Jagger biography at". AllMusic. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- Wiederhorn, Jon (6 December 2013). "Chris Jagger Keeps on Grooving With a Little Help From Big Brother Mick". Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- Jagger et al. 2003, p. 13.

- Nelson, Murray N. (2010). The Rolling Stones: A Musical Biography. p. 8. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood.

- "BBC News | ENTERTAINMENT | Jagger's family affair at school". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- White, Charles (2003). The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Authorised Biography. London: Omnibus Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 0-7119-9761-6.

- "Mick Jagger | The Rolling Stones". www.rollingstones.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "The 17 most successful alumni from the London School of Economics". Business Insider. 22 May 2016. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- Tremlet, George (1974). The Rolling Stones Story. London: Futura Publications Ltd. pp. 109–110. ISBN 0-7274-0123-8.

- Andersen 2012, p. 49.

- "The Rolling Stones Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Richards 2010, p. 97.

- "Speed Read: 11 Juiciest Bits from Philip Norman's Biography of Mick Jagger". The Daily Beast. 1 October 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "Mick Jagger Remembers". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Jagger et al. 2003, p. 84.

- Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 165. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- "100 Greatest Rolling Stones Songs". Rolling Stone. 15 October 2013. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Kot, Greg (2014). I'll Take You There: Mavis Staples, the Staple Singers, and the March up Freedom's Highway. Simon and Schuster. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-4516-4787-7.

- Unterberger, Richie. "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- Wild, Chris. "Adorable, 21-year-old Mick Jagger gets his hair done". Mashable. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Dick, Luke; Reisch, George (7 November 2011). The Rolling Stones and Philosophy: It's Just a Thought Away. Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9759-9. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017.

- "The Rolling Stone 20th Anniversary Interview: Mick Jagger". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Hattenstone, Simon (8 September 2005). "Rock of ages". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Andersen 2012, pp. 148–149.

- Booth, Stanley (2000). The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones (2nd edition). A Capella Books. pp. 271–278. ISBN 1-55652-400-5.

- Jagger et al. 2003, p. 128.

- Davis, Stephen (11 December 2001). Old Gods Almost Dead: The 40-Year Odyssey of the Rolling Stones. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 978-0-7679-0956-3. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.

- Wyman 2002, p. 329.

- "The Rolling Stones Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- The Rolling Stones (1969). The Stones in the Park (DVD released 2006). Network Studios.

- "Mick Jagger: we will play same set list at Hyde Park gig as in 1969". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "HYDE PARK, LONDON SETLIST: 13TH JULY 2013 | The Rolling Stones". www.rollingstones.com. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "The Rolling Stones release iconic Hyde Park 1969 performance on Blu-ray". AXS. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Stargrove | Hampshire Garden Trust Research". AitThemes.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Bill, Janovitz (2013). Rocks off : 50 tracks that tell the story of The Rolling Stones (First U.S. ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 189–191. ISBN 978-1-250-02632-3. OCLC 811597730.

- The National (26 June 2016), Rolling Stones' Mobile Recording Truck | Inside Tour, archived from the original on 6 September 2017, retrieved 1 September 2017

- Andersen 2012, p. 247.

- "Why Mick Jagger Never Goes Out of Style". Vogue. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "The world's greatest band, captured in its prime". Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "The Best Rolling Stones Songs That Don't Really Sound Like the Rolling Stones". Pitchfork. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Brown, Mark; correspondent, arts (17 March 2009). "Mick Jagger's jumpsuit is a gas, gas, gas: V&A galleries open". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Hamilton, Jack. "How 'Exile on Main St.' Killed the Rolling Stones". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Smith, Sid. "BBC – Music – Review of The Rolling Stones – Exile On Main St". Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Hall, Russell (20 February 2008). "Deepest Cut: The Rolling Stones Let It Loose from 1972's Exile on Main St.". Gibson Lifestyle.

- "10 Questions for Ron Wood". Time. 24 October 2007. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015.

- "Jamming with Edward! – The Rolling Stones | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "45 Years Ago: Rolling Stones Members Release 'Jamming With Edward!'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Stepping Out: Mick Jagger Goes Solo". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Pareles, John (19 February 1985). "Mick Jagger: She's The Boss". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017.

- "100 Best Singles of 1984: Pop's Greatest Year". Rolling Stone. 17 September 2014. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- Kurlansky, Mark (11 July 2013). Ready For a Brand New Beat: How "Dancing in the Street" Became the Anthem for a Changing America. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-61626-0. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017.

- "Mick Jagger Tour Rolls in Japan". Rolling Stone. 5 May 1988. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015.

- Hochman, Steve (4 October 1992). "Odd Couple Mick and Rick Finish Album". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Keith Richards: Rock's Main Offender". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Inc, Nielsen Business Media (24 November 2001). Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. p. 16.

mick jagger Atlantic Records solo career list of albums.

- "Mick Jagger – UK Charts" Archived 20 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Official Charts Company.

- "Wandering Spirit". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Mick Jagger – Billboard Charts". Billboard. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017.

- "MICK JAGGER | full Official Chart History | Official Charts Company". www.officialcharts.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Concert for New York City – Various Artists". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016.

- "Inside the Rolling Stones Inc. (Fortune, 2002)". Fortune. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Entertainment | Stones start monster tour". BBC News. 6 September 2002. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "Another Stones record – this one in Guinness". MSNBC. 26 September 2007. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Entertainment | Jagger vows to keep music rolling". BBC News. 2 October 2007. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "The 25th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame Concerts (4CD)". Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- Greene, Andy (20 May 2011). "Mick Jagger Forms Supergroup with Dave Stewart, Joss Stone and Damian Marley". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- Petridis, Alexis (15 September 2011). "SuperHeavy: SuperHeavy – review". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Hung, Steffen. "Discographie SuperHeavy – austriancharts.at". austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Mick Jagger's New Group SuperHeavy Unveils Music". Billboard. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "New Music: will.i.am f/ Jennifer Lopez & Mick Jagger – 'T.H.E (The Hardest Ever)'". Rap-Up.com. 18 November 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- "Mick Jagger, B.B. King Celebrate the Blues with President Obama". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "Mick Jagger helps 'Saturday Night Live' close out its season". CBS News. 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- Martens, Todd (12 December 2012). "12–12–12 Concert: The Rolling Stones make a quick exit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 29 December 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- Lynskey, Dorian (30 June 2013). "Rolling Stones at Glastonbury 2013 – review". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Rolling Stones to return to Hyde Park". BBC News. 3 April 2013. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013.

- "Rolling Stones Release 'Hyde Park Live' Album". Billboard. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- "Mick Jagger duets with singer brother on new album – MSN Music News". MSN. 7 December 2013. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "Mick Jagger has written not one, but two hideous songs about Brexit". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Brown, August (27 July 2017). "Mick Jagger releases two new, politically charged singles". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Blistein, Jon (27 July 2017). "Mick Jagger Gets Political, Addresses U.K. 'Anxiety' on Two New Songs". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "The Rolling Stones postpone tour due to Mick Jagger's health". The Guardian. Press Association. 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- Nedelman, Michael. "Mick Jagger's having his heart valve replaced. The technology is better than ever". CNN. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Brooks, Dave (4 April 2019). "Mick Jagger Undergoes Successful Heart Valve Procedure". Metro. UK. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- Dosani, Rishma (5 April 2019). "Mick Jagger 'recovering in hospital after successful heart surgery' as Rolling Stones postpone tour". Metro. UK. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- Greene, Andy; Greene, Andy (16 May 2019). "Rolling Stones Announce Rescheduled Dates For 2019 'No Filter' Tour". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "IrelandOn-Line". Archived from the original on 12 November 2013.

- "Entertainment | Stones row over Jagger knighthood". BBC News. 4 December 2003. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- Holden, Stephen (12 October 1988). "The Pop Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "The 25 Boldest Career Moves in Rock History: 20) Mick Jagger Tours Solo With Joe Satriani". Rolling Stone. 18 March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Sandford 1999, p. 268.

- Jagger et al. 2003, p. 247.

- "RIAA Gold & Platinum database". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Patell 2011, p. 24.

- Richards, Keith (2010). Life. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-03438-8. OCLC 548642133.

- Bloxham, Andy (15 October 2010). "Keith Richards: 'Mick Jagger has been unbearable since 1980s'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 September 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Keith Richards blasts heavy metal, rap in interview". Archived from the original on 25 December 2015.

- "NMA Collections Search – Facsimile of Ned Kelly's helmet". Nma.gov.au. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Dietz, Dan (3 September 2015). The Complete Book of 1970s Broadway Musicals. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-5166-3. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017.

- "'The Rocky Horror Picture Show' Remake: Major Character Casting Now Complete". The Inquisitr. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "We Got the Dune We Deserved: Jodorowsky's Dune". Tor.com. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- "Jodorowsky's Dune: The greatest acid sci-fi cult film never made". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 August 2014. Archived from the original on 30 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- Malcolm, Derek (12 January 2000). "Les Blank: Burden of Dreams". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Cox, Alex (21 January 2016). Alex Cox's Introduction to Film: A Director's Perspective. Oldcastle Books. ISBN 978-1-84344-747-4. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017.

- Faulk, Dr Barry; Harrison, Professor Brady (28 April 2014). Punk Rock Warlord: the Life and Work of Joe Strummer. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4724-1055-9. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017.

- "25 Years Ago: Mick Jagger Returns to the Movies in 'Freejack'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Holden, Stephen (26 November 1997). "Movie Review – Film Review; Sent From Gay Berlin To Labor at Dachau". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Scott, A.O. (2 October 2002). "Movie Review – Film Review; It May Sound Like Faust, But the Body Is the Lure". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "The Man From Elysian Fields". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Wynter Bee, Peter (2007). People of the Day 2. 2. People of the Day Limited. p. 81.

- "Jagger's New Swagger: Mick Moves to Movies, Blasts Idea of Memoir". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "Where to Watch Being Mick". Reelgood.com. 4 May 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Ascher, Rebecca (5 November 2004). "Long-planned remake of 'The Women' in development". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "The Women at". Hollywood.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "Shine a Light | Movies". OutNow.CH. 17 April 2008. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- McCarthy, Todd (7 February 2008). "Review: 'Shine a Light'". Variety. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- Morfoot, Addie (22 July 2014). "Mick Jagger on James Brown: 'He Was Very Generous and Kind With Me and He Wasn't Kind With Everybody'". Variety. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Andreeva, Nellie (22 June 2016). "'Vinyl' Canceled: HBO Scraps Plans For Revamped Season 2". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Johnny Depp, Keith Richards to Begin Fourth 'Pirates' – Mick Jagger rumored for fourth 'Pirates'". My Fox Houston. 26 April 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- McNary, Dave (6 September 2018). "Mick Jagger Joins Heist Thriller 'Burnt Orange Heresy'". Variety. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Millar, Stuart (14 August 1999), "Jagger and Jerry split made final", The Guardian, archived from the original on 4 October 2015, retrieved 8 October 2015

- "Jagger marriage annulled". BBC News, BBC. 13 August 1999. Archived from the original on 28 October 2002. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- Faithfull, Marianne (1994). Faithfull: An autobiography, Marianne Faithfull. London, England: Cooper Square Press. p. 198. ISBN 9783861501169.

- Harry, Bill (2000). The Beatles Encyclopaedia (2000 paperback edition; first published 1992). London, UK: Virgin Publishing. p. 403. ISBN 0-7535-0481-2.

- Ann Kolson, "Marsha Hunt's Life is Filled with 'Joy': The Irrepressible Performer has Mick Jagger in her past, old ties to Philadelphia, and a New Book", Philadelphia Inquirer, 16 February 1991.

- "Mick Jagger's love letters to Marsha Hunt reveal 'secret history' of". The Independent. 12 November 2012. Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Fonseca, Nicholas. "Limited Engagement". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- "Landlord files to have Bianca Jagger evicted". CNN. 6 April 2005. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- "Bianca Jagger bio at Huffington Post". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "20/20". Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- Fonseca, Nicholas (18 May 2001). "Limited Engagement". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "Carla Bruni on her affair with Mick Jagger: 'I thought I'd never fall in love with someone else'". 16 July 2012. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- "Settled: Jagger Child Support". People. 26 May 1998. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- "Mick Jagger's brood: Seven children aged 17 to 46 with five mothers — and now an eighth". National Post. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Sophie Dahl: Who are you calling a vulgar pin-up girl?". 24 June 2001. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- "Mick and Jerry Divorce". Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- Martinez, Andres (6 April 2005). "Landlord files to have Bianca Jagger evicted". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010.

- "Women in Luxury". Time. 4 September 2008. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- "L'Wren Scott leaves entire estate to Mick Jagger". Houston Chronicle. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- "Mick Jagger Donates Central Saint Martin's Scholarship to Honor L'Wren Scott". Fashionista. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016.

- "First photographs of Mick Jagger's eighth child, Deveraux, released by girlfriend". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Melanie Hamrick shares photo of baby with Mick Jagger". Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Mick Jagger Welcomes Eighth Child, Is a Dad Again at Age 73!". Us Weekly. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Eighth Child on the Way for Mick Jagger". People. 14 July 2016. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Barry Egan (31 August 2008). "I'm lucky that I grew up poor". The Irish Independent. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Milligan, Lauren (23 September 2013). "Mick Jagger: The World's Most Entertaining Great-Grandfather?". Vogue. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Reed, Ryan (19 May 2014). "Mick Jagger Becomes a Great-Grandfather". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "Mick Jagger names his eighth child Deveraux Octavian Basil". The Guardian. 16 December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- "Jagger's father dies of pneumonia". BBC News. 12 November 2006. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "So what if Jagger went on stage a few hours after his father died? What was he supposed to do?". The Guardian. 13 November 2006. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "Mick Jagger's father dies at 93". MSNBC. Associated Press. 12 November 2006. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- Edwards, Adam. "RIP Jumping Jack Flash senior". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- Ratcliffe, Hannah (15 July 2010). "Sir Mick Jagger visits his old school in Dartford". BBC. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "Cricinfo – Money talks". Content-www.cricinfo.com. 24 April 2008. Archived from the original on 1 August 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- "Jagger: I'm having a really good time". FIFA. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014.

- "World Cup 2014: Brazil fans blame 'curse of Mick Jagger' for their 7–1 defeat to Germany". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "Mick Jagger serves as inspiration for Monty Python live concerts". Fox News Channel. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- "Mick Jagger's admiration for Margaret Thatcher". The Guardian. 12 June 2013. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Everitt, Anthony. "Joining in: Investigation into Participatory Music in the UK". epdf.pub. p. 48. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "1991-2000 – The Musicians' Union: A History (1893-2013)". Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Mick Jagger pulls out of David Cameron hosted political event – NME". NME. 25 January 2012. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Celebrities' open letter to Scotland – full text and list of signatories". The Guardian. 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- "Sir Mick Jagger joins 200 public figures calling for Scotland to stay in the UK". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Mick Jagger shares his views on Brexit and the EU referendum". NME. 6 April 2016. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Mick Jagger can't get no satisfaction from Brexit". POLITICO. 28 July 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Mick Jagger Condemns Trump Administration's Climate Change Stance". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "No. 56595". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 15 June 2002. p. 1.

- "Stones frontman becomes Sir Mick". BBC. 12 December 2003. Archived from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- "Mick Jagger Knighted". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- Fricke, David. "Dancing with mister D: Keith richards – the rolling stone interview". Rolling Stone.

- "McCartney and John top Jubilee gig". BBC. 26 February 2002. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Stars line up for Jubilee concerts". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- Jagger et al. 2003, p. 289.

- Susman, Gary (12 December 2003). "Arise, Sir Mick: Jagger gets knighted, Mick Jagger". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Michaels, Sean (11 September 2014). "Mick Jagger has 19-million-year-old species of 'long-legged pig' named after him". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Andersen 2012, p. 3.

- Andersen 2012, pp. 179–180.

- Andersen 2012, p. 274.

- Andersen 2012, p. 314.

- Andersen 2012, p. 139.

- Andersen 2012, p. 265.

- Andersen 2012, p. 228.

- "Mick Jagger – The Photobook – UK". Contrasto Books. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- Cartner-Morley, Jess; Mirren, Helen; Huffington, Arianna; Amos, Valerie (28 March 2013). "The 50 best-dressed over 50s". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016.

- "Mick Jagger's Supergroup: SuperHeavy". ABC News. Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- "30 facts for 30 years – The truth about 'Spitting Image'". ITV. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- McMillian, John (2013). Beatles Vs. Stones. Simon and Schuster. p. 227.

- "New faces on Sgt Pepper album cover for artist Peter Blake's 80th birthday". The Guardian. 9 November 2016. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016.

- Philip Norman, Symphony for the Devil: the Rolling Stones Story, p.173. Linden Press/Simon & Schuster, 1984.

- Pattie, David (2007). Rock music in performance. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-4039-4746-8.

- Whiteley, Sheila (1997). Sexing the groove: popular music and gender. Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 0-415-14670-4.

- Frith, Simon (1998). Performing rites: on the value of popular music. Harvard University Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-674-66196-6.

- Australasian journal of American studies, Volume 20, 2001, p.107. Available at 1 Archived 18 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Consulted on 3 October 2011.

- Van Zandt, Steven (18 August 2015). "100 Greatest Artists: The Rolling Stones". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011.

- "Mick Jagger gets political on two new songs". MSN. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "The 25 Best Rock Frontmen (and Women) of All Time". Billboard. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "Top 10 Mick Jagger Rolling Stones Songs". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Sandford, Christopher (22 August 1998). Bowie: Loving the Alien. Time Warner. pp. 29–30. ISBN 0-306-80854-4.

- Price, Steven D. (2007). 1001 Insults, Put-Downs, & Comebacks. Globe Pequot. p. 172.

- Lenny Kravitz. "100 Greatest Singers: Mick Jagger Archived 10 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine". Rolling Stone. Consulted on 3 October 2011.

- ""Jon Bon Jovi: 'I Don't Know How The Hell Mick Jagger Does It'". StarPulse. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011."

- Bolen, Jean Shinoda (1989). Gods in everyman: a new psychology of men's lives and loves. Harper & Row. p. 257. ISBN 0-06-250098-8.

- Blake, John (18 February 2017). "I've got Mick Jagger's lost memoir". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017.

- Lawrence, Will (May 2008). "King Charles". Q. No. 262. p. 46.

- Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 277. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- Australian chart peaks:

- Top 100 (Kent Music Report) peaks to 19 June 1988: Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (Illustrated ed.). St. Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 153. ISBN 0-646-11917-6. N.B. the Kent Report chart was licensed by ARIA between mid 1983 and 19 June 1988.

- Top 50 (ARIA Chart) peaks from 26 June 1988: "australian-charts.com > Mick Jagger in Australian Charts". Hung Medien. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Top 100 (ARIA Chart) peaks from January 1990 to December 2010: Ryan, Gavin (2011). Australia's Music Charts 1988–2010. Mt. Martha, VIC, Australia: Moonlight Publishing.

- "British album certifications – Mick Jagger". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 20 August 2019. Select albums in the Format field. Type Mick Jagger in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- "Gold/Platinum". RIAA. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- https://www.billboard.com/music/nicky-hopkins/chart-history/TLP/song/827724

- "charts.de". charts.de. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "Irish Singles Chart – Search for song". Irish Recorded Music Association. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- "Jungle Madness". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Lawson, Carol (23 March 1981). "Herzog Jungle Film Halts As Ill Robards Leaves". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

Sources

- Andersen, Christopher (2012). Mick: The Wild Life and Mad Genius of Jagger. New York: Simon and Schuster, Gallery Books. ISBN 978-1-4516-6146-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Greenfield, Robert (1981). The Rolling Stone Interviews: Keith Richards. New York: St. Martin's Press/Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 978-0-312-68954-4.

- Jagger, Mick; Richards, Keith; Watts, Charlie; Wood, Ronnie (2003). According to the Rolling Stones. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-4060-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)