Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture (or pointed architecture) is an architectural style that flourished in Europe during the High and Late Middle Ages.[1] It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture. It originated in 12th-century northern France and England as a development of Norman architecture.[2] Its popularity lasted into the 16th century, before which the style was known as Latin: opus Francigenum, lit. 'French work'; the term Gothic was first applied during the later Renaissance.

_08.jpg)  Top: Basilica of Saint-Denis, Brussels Cathedral: Centre: Cologne Cathedral, Chartres Cathedral; Bottom:Gloucester Cathedral | |

| Years active | 12th–17th centuries. |

|---|---|

| Influenced | Gothic Revival architecture |

The defining element of Gothic architecture is the pointed or ogival arch. It is the primary engineering innovation and the characteristic design component. The use of the pointed arch in turn led to the development of the pointed rib vault and flying buttresses, combined with elaborate tracery and stained glass windows.[3]

At the Abbey of Saint-Denis, near Paris, the choir was reconstructed between 1140 and 1144, drawing together for the first time the developing Gothic architectural features. In doing so, a new architectural style emerged that internally emphasised verticality in the structural members, and the effect created by the transmission of light through stained glass windows.[4]

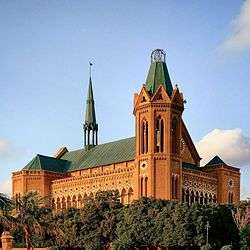

Survivals of medieval Gothic architecture are most common as Christian ecclesiastical architecture, in the cathedrals, abbeys, and parish churches of Europe. It is also the architecture of many castles, palaces, town halls, guildhalls, universities and, less prominently today, private dwellings. Many of the finest examples of mediaeval Gothic architecture are listed with UNESCO as World Heritage Sites.

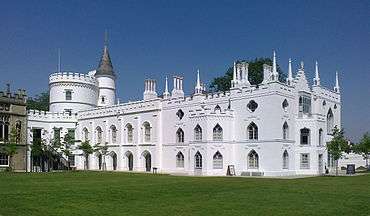

With the development of Renaissance architecture in Italy during the mid 15th century, the Gothic style was supplanted by the new style, but in some regions, notably England, Gothic continued to flourish and develop into the 16th century. A series of Gothic revivals began in mid-18th century England, spread through 19th-century Europe and continued, largely for ecclesiastical and university structures, into the 20th century.

Name

Gothic architecture is also known as pointed architecture or ogival architecture.[5][6] Mediaeval contemporaries described the style as Latin: opus Francigenum, lit. 'French work' or 'Frankish work', as opus modernum, 'modern work', novum opus, 'new work', or as Italian: maniera tedesca, lit. 'German style'.[7][8]

The term "Gothic architecture" originated as a pejorative description. Giorgio Vasari used the term "barbarous German style" in his Lives of the Artists to describe what is now considered the Gothic style,[9] and in the introduction to the Lives he attributes various architectural features to the Goths, whom he held responsible for destroying the ancient buildings after they conquered Rome, and erecting new ones in this style.[10] When Vasari wrote, Italy had experienced a century of building in the Vitruvian architectural vocabulary of classical orders revived in the Renaissance and seen as evidence of a new Golden Age of learning and refinement. Vasari was echoed in the 16th century by François Rabelais, who referred to Goths and Ostrogoths (Gotz and Ostrogotz).[lower-alpha 1][11]

The polymath architect Christopher Wren was disapproving of the name Gothic for pointed architecture. He compared it with Islamic architecture, which he called the 'Saracen style', pointing out that the pointed arch's sophistication was not owed to the Goths but to the Islamic Golden Age. He wrote:[12]

This we now call the Gothic manner of architecture (so the Italians called what was not after the Roman style) though the Goths were rather destroyers than builders; I think it should with more reason be called the Saracen style, for these people wanted neither arts nor learning: and after we in the west lost both, we borrowed again from them, out of their Arabic books, what they with great diligence had translated from the Greeks

— Christopher Wren, Report on St Paul's

According to a 19th-century correspondent in the London journal Notes and Queries, Gothic was a derisive misnomer; the pointed arcs and architecture of the later Middle Ages was quite different to the rounded arches prevalent in late antiquity and the period of the Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy:

There can be no doubt that the term 'Gothic' as applied to pointed styles of ecclesiastical architecture was used at first contemptuously, and in derision, by those who were ambitious to imitate and revive the Grecian orders of architecture, after the revival of classical literature. But, without citing many authorities, such as Christopher Wren, and others, who lent their aid in depreciating the old mediaeval style, which they termed Gothic, as synonymous with every thing that was barbarous and rude, it may be sufficient to refer to the celebrated Treatise of Sir Henry Wotton, entitled The Elements of Architecture, ... printed in London so early as 1624. ... But it was a strange misapplication of the term to use it for the pointed style, in contradistinction to the circular, formerly called Saxon, now Norman, Romanesque, &c. These latter styles, like Lombardic, Italian, and the Byzantine, of course belong more to the Gothic period than the light and elegant structures of the pointed order which succeeded them.[13]

Periods

Architecture "became a leading form of artistic expression during the late Middle Ages".[2] Gothic architecture began in the earlier 12th century in northwest France and England and spread throughout Latin Europe in the 13th century; by 1300, a first "international style" of Gothic had developed, with common design features and formal language. A second "international style" emerged by 1400, alongside innovations in England and central Europe that produced both the perpendicular and flamboyant varieties. Typically, these typologies are identified as:[2]

- c.1130–c.1240 Early to High Gothic and Early English

- c.1240–c.1350 Rayonnant and Decorated Style

- c.1350–c.1500 Late Gothic: flamboyant and perpendicular

Abbey church of Saint-Denis, west façade

Abbey church of Saint-Denis, west façade Nave of Sens Cathedral (1135-1176)

Nave of Sens Cathedral (1135-1176) Nave of Notre-Dame de Paris (1163-1345)

Nave of Notre-Dame de Paris (1163-1345)

History

.jpg)

Sens Cathedral

Early Gothic

Norman architecture on either side of the English Channel developed in parallel towards Early Gothic.[2] Gothic features, such as the rib vault, had appeared in England and Normandy in the 11th century.[2] Rib-vaults were employed in the cathedral at Durham (1093–)[2] and in Lessay Abbey in Normandy (1098).[14] However, the first buildings to be considered fully Gothic are the royal funerary abbey of the French kings, the Abbey of Saint-Denis (1134–44), and the archiepiscopal cathedral at Sens (1143–63) They were the first buildings to systematically combine rib vaulting, buttresses, and pointed arches.[2] Most of the characteristics of later Early English were already present in the lower chevet of Saint-Denis.[1]

The Duchy of Normandy, part of the Angevin Empire until the 13th century, developed its own version of Gothic. One of these was the Norman chevet, a small apse or chapel attached to the choir at the east end of the church, which typically had a half-dome. The lantern tower was another common feature in Norman Gothic.[14] One example of early Norman Gothic is Bayeux Cathedral (1060–70) where the Romanesque cathedral nave and choir were rebuilt into the Gothic style. Lisieux Cathedral was begun in 1170.[15] Rouen Cathedral (begun 1185) was rebuilt from Romanesque to Gothic with distinct Norman features, including a lantern tower, deeply moulded decoration, and high pointed arcades.[16] Coutances Cathedral was remade into Gothic beginning about 1220. Its most distinctive feature is the octagonal lantern on the crossing of the transept, decorated with ornamental ribs, and surrounded by sixteen bays and sixteen lancet windows.[15]

Saint-Denis was the work of the Abbot Suger, a close adviser of Kings Louis VI and Louis VII. Suger reconstructed portions of the old Romanesque church with the rib vault in order to remove walls and to make more space for windows. He described the new ambulatory as "a circular ring of chapels, by virtue of which the whole church would shine with the wonderful and uninterrupted light of most luminous windows, pervading the interior beauty."[17] To support the vaults He also introduced columns with capitals of carved vegetal designs, modelled upon the classical columns he had seen in Rome. In addition, he installed a circular rose window over the portal on the facade.[17] These also became a common feature of Gothic cathedrals.[17][18]

The elements of Gothic style appeared very early in England. Durham Cathedral was the first cathedral to employ a rib vault, built between 1093 and 1104.[19] The monk-historian William of Malmesbury wrote of the Norman style at the beginning of the 12th century, "you can see everywhere, in the churches in the cities and the monasteries in the villages and towns, being built a new type of construction and flourishing in a new modern style."[20]

The first cathedral in France built entirely in the new style was Sens Cathedral, begun between 1135 and 1140 and consecrated in 1160.[21][22] Sens Cathedral features a Gothic choir, and six-part rib vaults over the nave and collateral aisles, alternating pillars and doubled columns to support the vaults, and buttresses to offset the outward thrust from the vaults. One of the builders who is believed to have worked on Sens Cathedral, William of Sens, later travelled to England and became the architect who, between 1175 and 1180, reconstructed the choir of Canterbury Cathedral in the new Gothic style.[21]

Sens Cathedral was influential in its strongly vertical appearance and in its three-part elevation, typical of subsequent Gothic buildings, with a clerestory at the top supported by a triforium, all carried on high arcades of pointed arches.[23] In the following decades flying buttresses began to be used, allowing the construction of lighter, higher walls.[23] French Gothic churches were heavily influenced both by the ambulatory and side-chapels around the choir at Saint-Denis, and by the paired towers and triple doors on the western façade.[23]

Sens was quickly followed by Senlis Cathedral (begun 1160), and Notre-Dame de Paris (begun 1160). Their builders abandoned the traditional plans and introduced the new Gothic elements from Saint-Denis. The builders of Notre-Dame went further by introducing the flying buttress, heavy columns of support outside the walls connected by arches to the upper walls. The vaults received and counterbalanced the outward thrust from the rib vaults of the roof. This allowed the builders to construct higher walls and larger windows.[24]

Metz Cathedral (1220–)

Early English and High Gothic

Following the destruction by fire of the choir of Canterbury Cathedral in 1174, a group of master builders was invited to propose plans for the reconstruction. The master-builder William of Sens, who had worked on Sens Cathedral, won the competition.[23] Work began that same year, but in 1178 William was badly injured by fall from the scaffolding, and returned to France, where he died.[25][26] His work was continued by William the Englishman who replaced his French namesake in 1178. The resulting structure of the choir of Canterbury Cathedral is considered the first work Early English Gothic.[23] The cathedral churches of Worcester (1175–), Wells (c.1180–), Lincoln (1192–), and Salisbury (1220–) are all, with Canterbury, major examples.[23] Tiercerons – decorative vaulting ribs – seem first to be have been used in vaulting at Lincoln Cathedral, installed c.1200.[23] Instead of a triforium, Early English churches usually retained a gallery.[23]

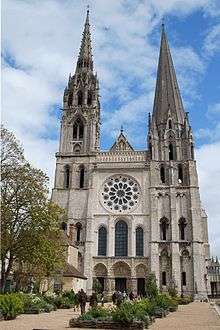

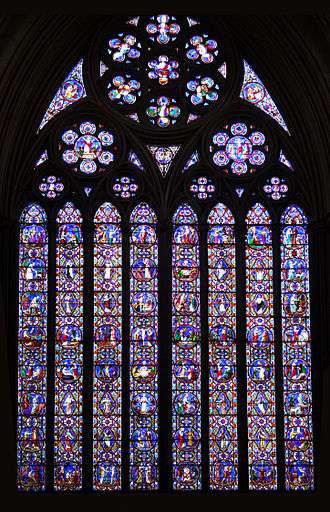

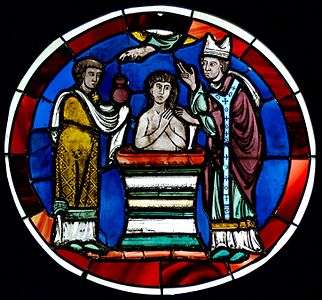

High Gothic (c. 1194–1250) was a brief but very productive period, which produced some of the great landmarks of Gothic art. The first building in the High Gothic (French: Classique) was Chartres Cathedral, an important pilgrimage church south of Paris. The Romanesque cathedral was destroyed by fire in 1194, but was swiftly rebuilt in the new style, with contributions from King Philip II of France, Pope Celestine III local gentry, merchants and craftsmen and Richard the Lionheart, king of England. The builders simplified the elevation used at Notre Dame, eliminated the tribune galleries, and used flying buttresses to support the upper walls. The walls were filled with stained glass, mainly depicting the story of the Virgin Mary but also, in a small corner of each window, illustrating the crafts of the guilds who donated those windows.[27]

The model of Chartres was followed by a series of new cathedrals of unprecedented height and size. These were Reims Cathedral (begun 1211), where coronations of the kings of France took place; Amiens Cathedral (1220–1226); Bourges Cathedral (1195–1230) (which, unlike the others, continued to use six-part rib vaults); and Beauvais Cathedral(1225–).[23][28]

In central Europe, the High Gothic style appeared in the Holy Roman Empire, first at Toul (1220–), whose Romanesque cathedral was rebuilt in the style of Reims Cathedral; then Trier's Liebfrauenkirche parish church (1228–), and then throughout the Reich, beginning with the Elisabethkirche at Marburg (1235–) and the cathedral at Metz (c.1235–).[23]

In High Gothic, the whole surface of the clerestory was given over to windows. At Chartres Cathedral, plate tracery was used for the rose window, but at Reims the bar-tracery was free-standing.[23] Lancet windows were supplanted by multiple lights separated by geometrical bar-tracery.[5] Tracery of this kind distinguishes Middle Pointed style from the simpler First Pointed.[5] Inside, the nave was divided into by regular bays, each covered by a quadripartite rib vaults.[23]

Other characteristics of the High Gothic were the development of rose windows of greater size, using bar-tracery, higher and longer flying buttresses, which could reach up to the highest windows, and walls of sculpture illustrating biblical stories filling the facade and the fronts of the transept. Reims Cathedral had two thousand three hundred statues on the front and back side of the facade.[28]

The new High Gothic churches competed to be the tallest, with increasingly ambitious structures lifting the vault yet higher. Chartres Cathedral's height of 38 m (125 ft) was exceeded by Beauvais Cathedral's 48 m (157 ft), but on account of the latter's collapse in 1248, no further attempt was made to build higher.[23] Attention turned from achieving greater height to creating more awe-inspiring decoration.[28]

Strasbourg Cathedral (1276–)

Rayonnant Gothic and Decorated Style

Rayonnant Gothic maximised the coverage of stained glass windows such that the walls are effectively entirely glazed; notable examples are the nave of Saint-Denis (1231–) and the royal chapel of Louis IX of France on the Île de la Cité in the Seine – the Sainte-Chapelle (c.1241–8).[23] The high and thin walls of French Rayonnant Gothic allowed by the flying buttresses enabled increasingly ambitious expanses of glass and decorated tracery, reinforced with ironwork.[23] Shortly after Saint-Denis, in the 1250s, Louis IX commissioned the rebuilt transepts and enormous rose windows of Notre-Dame de Paris (1250s for the north transept, 1258 for the beginning of south transept).[29] This first 'international style' was also used in the clerestory of Metz Cathedral (c.1245–), then in the choir of Cologne's cathedral (c.1250–), and again in the nave of the cathedral at Strasbourg (c.1250–).[23] Masons elaborated a series of tracery patterns for windows – from the basic geometrical to the reticulated and the curvilinear – which had superseded the lancet window.[5] Bar-tracery of the curvilinear, flowing, and reticulated types distinguish Second Pointed style.[5]

Decorated Gothic similarly sought to emphasise the windows, but excelled in the ornamentation of their tracery. Churches with features of this style include Westminster Abbey (1245–), the cathedrals at Lichfield (after 1257–) and Exeter (1275–), Bath Abbey (1298–), and the retro choir at Wells Cathedral (c.1320–).[23]

The Rayonnant developed its second 'international style' with increasingly autonomous and sharp-edged tracery mouldings apparent in the cathedral at Clermont-Ferrand (1248–), the papal collegiate church at Troyes, Saint-Urbain (1262–), and the west façade of Strasbourg Cathedral (1276–).[23] By 1300, there were examples influenced by Strasbourg in the cathedrals of Limoges (1273–), Regensburg (c.1275–), and in the cathedral nave at York (1292–).[23]

Prague Cathedral (1344–)

Late Gothic: flamboyant and perpendicular

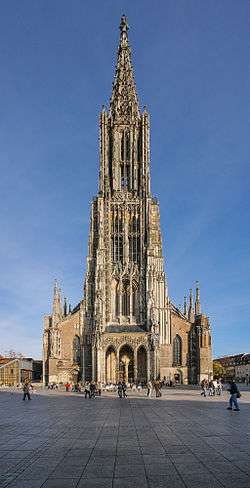

Central Europe began to lead the emergence of a new, international flamboyant style with the construction of a new cathedral at Prague (1344–) under the direction of Peter Parler.[23] This model of rich and variegated tracery and intricate reticulated rib-vaulting was definitive in the Late Gothic of continental Europe, emulated not only by the collegiate churches and cathedrals, but by urban parish churches which rivalled them in size and magnificence.[23] The minster at Ulm and other parish churches like the Heilig-Kreuz-Münster at Schwäbisch Gmünd (c.1320–), St Barbara's Church at Kutná Hora (1389–), and the Heilig-Geist-Kirche (1407–) and St Martin's Church (c.1385–) in Landshut are typical.[23] Use of ogees was especially common.[5]

The flamboyant style was characterised by the multiplication of the ribs of the vaults, with new purely decorative ribs, called tiercons and liernes, and additional diagonal ribs. One common ornament of flamboyant in France is the arc-en-accolade, an arch over a window topped by a pinnacle, which was itself topped with fleuron, and flanked by other pinnacles. Notable examples of French flamboyant building include the west façade of Rouen Cathedral, and especially the façades of Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes (1370s) and choir Mont-Saint-Michel's abbey church (1448).[24]

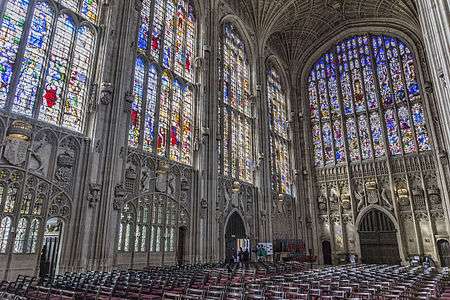

In England, ornamental rib-vaulting and tracery of Decorated Gothic co-existed with, and then gave way to, the perpendicular style from the 1320s, with straightened, orthogonal tracery topped with fan-vaulting.[5][23] Perpendicular Gothic was unknown in continental Europe and unlike earlier styles had no equivalent in Scotland or Ireland.[5][30] It first appeared in the cloisters and chapter-house (c. 1332) of Old St Paul's Cathedral in London by William de Ramsey.[30] The chancel of Gloucester Cathedral (c. 1337–57) and its latter 14th century cloisters are early examples.[30] Four-centred arches were often used, and lierne vaults seen in early buildings were developed into fan vaults, first at the latter 14th century chapter-house of Hereford Cathedral (demolished 1769) and cloisters at Gloucester, and then at Reginald Ely's King's College Chapel, Cambridge (1446–1461) and the brothers William and Robert Vertue's Henry VII Chapel (c. 1503–12) at Westminster Abbey.[30][31][32] Perpendicular is sometimes called Third Pointed and was employed over three centuries; the fan-vaulted staircase at Christ Church, Oxford built around 1640.[5][30]

Lacey patterns of tracery continued to characterise continental Gothic building, with very elaborate and articulated vaulting, as at St Barbara's, Kutná Hora (1512).[5] In certain areas, Gothic architecture continued to be employed until the 17th and 18th centuries, especially in provincial and ecclesiastical contexts, notably at Oxford.[5] Though fallen from favour from the Renaissance on, Gothic architecture survived the early modern period and flourished again in a revival from the late 18th century and throughout the 19th.[5] Perpendicular was the first Gothic style revived in the 18th century.[30]

Influences

Political

At the end of the 12th century, Europe was divided into a multitude of city states and kingdoms. The area encompassing modern Germany, southern Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Austria, Slovakia, Czech Republic and much of northern Italy (excluding Venice and Papal States) was nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire, but local rulers exercised considerable autonomy. France, Denmark, Poland, Hungary, Portugal, Scotland, Castile, Aragon, Navarre, and Cyprus were independent kingdoms, as was the Angevin Empire, whose Plantagenet kings ruled England and large domains in what was to become modern France.[33] Norway came under the influence of England, while the other Scandinavian countries and Poland were influenced by trading contacts with the Hanseatic League. Angevin kings brought the Gothic tradition from France to Southern Italy, part of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, while after the First Crusade the Lusignan kings introduced French Gothic architecture to Cyprus and the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Throughout Europe at this time there was a rapid growth in trade and an associated growth in towns.[34][35] Germany and the Lowlands had large flourishing towns that grew in comparative peace, in trade and competition with each other, or united for mutual weal, as in the Hanseatic League. Civic building was of great importance to these towns as a sign of wealth and pride. England and France remained largely feudal and produced grand domestic architecture for their kings, dukes and bishops, rather than grand town halls for their burghers.

Religious

The Roman Catholic Church prevailed across Western Europe at this time, influencing not only faith but also wealth and power. Bishops were appointed by the feudal lords (kings, dukes and other landowners) and they often ruled as virtual princes over large estates. The early mediaeval periods had seen a rapid growth in monasticism, with several different orders being prevalent and spreading their influence widely. Foremost were the Benedictines whose great abbey churches vastly outnumbered any others in France, Normandy and England. A part of their influence was that towns developed around them and they became centres of culture, learning and commerce. They were the builders of the Abbey of Saint-Denis, and Abbey of Saint-Remi in France. Later Benedictine projects (constructions and renovations) include Rouen's Abbey of Saint-Ouen, the Abbey La Chaise-Dieu, and the choir of Mont Saint-Michel in France. English examples are Westminster Abbey, originally built as a Benedictine order monastic church; and the reconstruction of the Benedictine church at Canterbury.

The Cluniac and Cistercian Orders were prevalent in France, the great monastery at Cluny having established a formula for a well planned monastic site which was then to influence all subsequent monastic building for many centuries.[34][35] The Cistercians spread the style as far east and south as Poland and Hungary.[36] Smaller orders such as the Carthusians and Premonstratensians also built some 200 churches, usually near cities.[37]

In the 13th century Francis of Assisi established the Franciscans, or so-called "Grey Friars", a mendicant order. Saint Dominic founded the mendicant Dominicans, in Toulouse and Bologna, were particularly influential in the building of Italy's Gothic churches.[34][35]

The Teutonic Order, a military order, spread Gothic art into Pomerania, East Prussia, and the Baltic region.[38]

Geographic

From the 10th to the 13th century, Romanesque architecture had become a pan-European style and manner of construction, affecting buildings in countries as far apart as Ireland, Croatia, Sweden and Sicily. The same wide geographic area was then affected by the development of Gothic architecture, but the acceptance of the Gothic style and methods of construction differed from place to place, as did the expressions of Gothic taste. The proximity of some regions meant that modern country borders do not define divisions of style.[34] On the other hand, some regions such as England and Spain produced defining characteristics rarely seen elsewhere, except where they have been carried by itinerant craftsmen, or the transfer of bishops. Regional differences that are apparent in the churches of the Romanesque period often become even more apparent in the Gothic.[35]

The local availability of materials affected both construction and style. In France, limestone was readily available in several grades, the very fine white limestone of Caen being favoured for sculptural decoration. England had coarse limestone and red sandstone as well as dark green Purbeck marble which was often used for architectural features.

In Northern Germany, Netherlands, northern Poland, Denmark, and the Baltic countries local building stone was unavailable but there was a strong tradition of building in brick. The resultant style, Brick Gothic, is called "Backsteingotik" in Germany and Scandinavia and is associated with the Hanseatic League. In Italy, stone was used for fortifications, but brick was preferred for other buildings. Because of the extensive and varied deposits of marble, many buildings were faced in marble, or were left with undecorated façade so that this might be achieved at a later date.

The availability of timber also influenced the style of architecture, with timber buildings prevailing in Scandinavia. Availability of timber affected methods of roof construction across Europe. It is thought that the magnificent hammer-beam roofs of England were devised as a direct response to the lack of long straight seasoned timber by the end of the mediaeval period, when forests had been decimated not only for the construction of vast roofs but also for ship building.[34][39]

Romanesque tradition

Gothic architecture grew out of the previous architectural genre, Romanesque. For the most part, there was not a clean break, as there was to be later in Renaissance Florence with the revival of the Classical style in the early 15th century.

By the 12th century, builders throughout Europe developed Romanesque architectural styles (termed Norman architecture in England because of its association with the Norman Conquest).[40] Scholars have focused on categories of Romanesque/Norman building, including the cathedral church, the parish church, the abbey church, the monastery, the castle, the palace, the great hall, the gatehouse, the civic building, the warehouse, and others.[41]

Many architectural features that are associated with Gothic architecture had been developed and used by the architects of Romanesque buildings, particularly in the building of cathedrals and abbey churches. These include ribbed vaults, buttresses, clustered columns, ambulatories, wheel windows, spires, stained glass windows, and richly carved door tympana. These were already features of ecclesiastical architecture before the development of the Gothic style, and all were to develop in increasingly elaborate ways.[42]

It was principally the widespread introduction of a single feature, the pointed arch, which was to bring about the change that separates Gothic from Romanesque. This technological change permitted both structural and stylistic change which broke the tradition of massive masonry and solid walls penetrated by small openings, replacing it with a style where light appears to triumph over substance. With its use came the development of many other architectural devices, previously put to the test in scattered buildings and then called into service to meet the structural, aesthetic and ideological needs of the new style. These include the flying buttresses, pinnacles and traceried windows which typify Gothic ecclesiastical architecture.[34]

Oriental influence

The pointed arch, one of the defining attributes of Gothic, appears in Late Roman Byzantine architecture and the Sasanian architecture of Iran during late antiquity, although the form had been used earlier, as in the possibly 1st century AD Temple of Bel, Dura Europos in Roman Mesopotamia.[43] In the Roman context it occurred in church buildings in Syria and occasional secular structures, like the Karamagara Bridge in modern Turkey. In Sassanid architecture parabolic and pointed arches were employed in both palace and sacred construction.[44] A very slightly pointed arch built in 549 exists in the apse of the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe in Ravenna, and slightly more pointed example from a church, built 564 at Qasr Ibn Wardan in Roman Syria.[45] Pointed arches' development may have been influenced by the elliptical and parabolic arches frequently employed in Sasanian buildings using pitched brick vaulting, which obviated any need for wooden centring and which had for millennia been used in Mesopotamia and Syria.[46] The oldest pointed arches in Islamic architecture are in the Dome of the Rock, completed in 691/2, while some others appear in the Great Mosque of Damascus, begun in 705.[47] The Umayyads were responsible for the oldest significantly pointed arches in medieval western Europe, employing them alongside horseshoe arches in the Great Mosque of Cordoba, built from 785 and repeatedly extended.[48] The Abbasid palace at al-Ukhaidir employed pointed arches in 778 as a dominant theme both structural and decorative throughout the façades and vaults of the complex, while the tomb of al-Muntasir, built 862, employed a dome with a pointed arch profile. Abbasid Samarra had many pointed arches, notably its surviving Bab al-ʿAmma (monumental triple gateway). By the 9th century the pointed arch was used in Egypt and North Africa: in the Nilometer at Fustat in 861, the 876 Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, and the 870s Great Mosque of Kairouan. Through the 8th and 9th centuries, the pointed arch was employed as standard in secular buildings in architecture throughout the Islamic world.[49] The 10th century Aljafería at Zaragoza displays numerous forms of arch, including many pointed arches decorated and elaborated to a level of design sophistication not seen in Gothic architecture for a further two centuries.[48]

Increasing military and cultural contacts with the Muslim world, including the Norman conquest of Islamic Sicily between 1060 and 1090, the Crusades, beginning 1096, and the Islamic presence in Spain, may have influenced mediaeval Europe's adoption of the pointed arch, although this hypothesis remains controversial.[50] The structural advantages of pointed arches seems first to have been realised in a medieval Latin Christian context at the abbey church known as Cluny III at Cluny Abbey.[51] Begun by abbot Hugh of Cluny in 1089, the great Romanesque church of Cluny III was the largest church in the west when completed in 1130.[52] Kenneth John Conant, who excavated the site of the church's ruins, argued that the architectural innovations of Cluny III were inspired by the Islamic architecture of Sicily via Monte Cassino.[51] The Abbey of Monte Cassino was the foundational community of the Benedictine Order and lay within the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, which at that time was majority Muslim and predominantly Arabic-speaking. The rib vault with pointed arches was used at Lessay Abbey in Normandy in 1098,[53] and at Durham Cathedral in England at about the same time.[54] In those parts of the Western Mediterranean subject to Islamic control or influence, rich regional variants arose, fusing Romanesque, Byzantine and later Gothic traditions with Islamic decorative forms, as seen, for example, in Monreale and Cefalù Cathedrals, the Alcázar of Seville, and Teruel Cathedral.[55][56]

Structural elements

Pointed arches

One of the common characteristics the Gothic style is the pointed arch, which was widely used both in structure and decoration. The pointed arch did not originate in Gothic architecture; they had been employed for centuries in the Near East in pre-Islamic as well as Islamic architecture for arches, arcades, and ribbed vaults.[57] In Gothic architecture, particularly in the later Gothic styles, they became the most visible and characteristic element, giving a sensation of verticality and pointing upward, like the spires. Gothic rib vaults covered the nave, and pointed arches were commonly used for the arcades, windows, doorways, in the tracery, and especially in the later Gothic styles decorating the façades.[58] They were also sometimes used for more practical purposes, such as to bring transverse vaults to the same height as diagonal vaults, as in the nave and aisles of Durham Cathedral, built in 1093.[59]

The earliest Gothic pointed arches were lancet lights or lancet windows, narrow windows terminating in a lancet arch, an arch with a radius longer than their breadth and resembling the blade of a lancet.[60][61] In the 12th century First Pointed phase of Gothic architecture, also called the Lancet style and before the introduction of tracery in the windows in later styles, lancet windows predominated Gothic building.[62]

The Flamboyant Gothic style was particularly known for such lavish pointed details as the arc-en-accolade, where the pointed arch over a doorway was topped by a pointed sculptural ornament called a fleuron and by pointed pinnacles on either side. the arches of the doorway were further decorated with small cabbage-shaped sculptures called "chou-frisés".[63]

Eastern end of Wells Cathedral (begun 1175)

Eastern end of Wells Cathedral (begun 1175).jpg) West front of Reims Cathedral, pointed arches within arches (1211-1275)

West front of Reims Cathedral, pointed arches within arches (1211-1275)- Lancet windows of transept Salisbury Cathedral (1220-1258)

Pointed arches in the arcades, triforium and clerestory of Lincoln Cathedral (1185-1311)

Pointed arches in the arcades, triforium and clerestory of Lincoln Cathedral (1185-1311) A detail of the windows and galleries of the west front of Strasbourg Cathedral (1215-1439)

A detail of the windows and galleries of the west front of Strasbourg Cathedral (1215-1439)

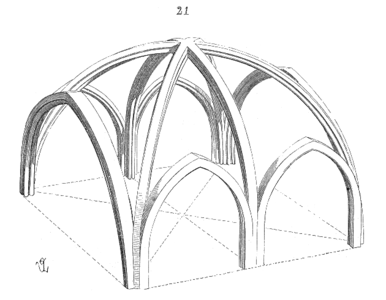

Rib vaults

The Gothic rib vault was one of the essential elements that made possible the great height and large windows of the Gothic style.[64] Unlike the semi-circular barrel vault vault of Roman and Romanesque buildings, where the weight pressed directly downward, and required thick walls and small windows, the Gothic rib vault was made of diagonal crossing arched ribs. These ribs directed the thrust outwards to the corners of the vault, and downwards via slender colonettes and bundled columns, to the pillars and columns below. The space between the ribs was filled with thin panels of small pieces of stone, which were much lighter than earlier groin vaults. The outward thrust against the walls was countered by the weight of buttresses and later flying buttresses. As a result, the massive thick walls of Romanesque buildings were no longer needed; Since the vaults were supported by the columns and piers, the walls could be thinner and higher, and filled with windows.[65][21][66]

The earlier Gothic rib vaults, used at Sens Cathedral (begun between 1135–40) and Notre-Dame de Paris (begun 1163), were divided by the ribs into six compartments. They were very difficult to build, and could only cross a limited space. Since each vault covered two bays, they needed support on the ground floor from alternating columns and piers. In later construction, the design was simplified, and the rib vaults had only four compartments. The alternating rows of alternating columns and piers receiving the weight of the vaults was replaced by simple pillars, each receiving the same weight. A single vault could cross the nave. This method was used at Chartres Cathedral (1194–1220), Amiens Cathedral (begun 1220), and Reims Cathedral.[67] The four-part vaults made it possible for the building to be even higher. Notre-Dame de Paris, begun in 1163 with six-part vaults, reached a height of 35 m (115 ft). Amiens Cathedral, begun in 1220 with the newer four-part ribs, reached the height of 42.3 m (139 ft) at the transept.[65][68]

Early six-part rib vaults in Sens Cathedral (1135-1164)

Early six-part rib vaults in Sens Cathedral (1135-1164) Rib vaults of choir of Canterbury Cathedral (1174–77)

Rib vaults of choir of Canterbury Cathedral (1174–77).jpg) Stronger four-part rib vaults in nave of Reims Cathedral (1211-1275)

Stronger four-part rib vaults in nave of Reims Cathedral (1211-1275) Salisbury Cathedral – rectangular four-part vault over a single bay (1220-1258)

Salisbury Cathedral – rectangular four-part vault over a single bay (1220-1258)

Later vaults (13th-15th century)

In France, the four-part rib vault, with a two diagonals crossing at the center of the traverse, was the type used almost exclusively until the end of the Gothic period. However, in England, several imaginative new vaults were invented which had more elaborate deoorative features. They became a signature of the later English Gothic styles.[69]

The first of these new vaults had an additional rib, called a tierceron, which ran down the median of the vault.[70] It first appeared in the vaults of the choir of Lincoln Cathedral at the end of the 12th century, and the at Worcester Cathedral in 1224, then the south transept of Lichfield Cathedral.[69]

The 14th century brought the invention of several new types of vaults which were more and more decorative.[71] These vaults often copied the forms form of the elaborate tracery of the Late Gothic styles.[70] These included the stellar vault, where a group of additional ribs between the principal ribs forms a star design. The oldest vaults of this kind were found in the crypt of Saint Stephen at Westminster Palace, built about 1320. A second type was called a reticulated vault, which featured an network of additional decorative ribs, in triangles and other geometric forms, placed between or over the traverse ribs. These were first used in the choir of Bristol Cathedral in about 1311. Another late Gothic form, the fan vault, with ribs spreading upwards and outwards, appeared later in the 14th century. A notable example in the cloister of Gloucester Cathedral (c. 1370).[69]

Another new form was the skeleton vault, which appeared in the English Decorated style. It features an additional network of ribs, like the ribs of an umbrella, which criss-cross the vault but are only directly attached to it at certain points. It appeared in a chapel of Lincoln Cathedral in 1300.[69] and then several other English churches. This style of vault was adopted in the 14th century in particular by German architects, particularly Peter Parler, and in other parts of central Europe. It was featured in the south porch of Prague Cathedral[69]

Exotic vaults also appeared in civic architecture. A notable example is the ceiling of the grand hall of Vladimir in Prague Castle in Bohemia. designed by The Prague city hall, and built by Benedikt Ried in 1493. The ribs twist and intertwine in fantasy patterns, which later critics called "Rocoro Gothic".[72]

- Lierne vaults of Gloucester Cathedral (Perpendicular Gothic)

Skeleton-vault in aisle of Bristol Cathedral (c. 1311-1340)

Skeleton-vault in aisle of Bristol Cathedral (c. 1311-1340) Lincoln Cathedral – quadripartite form, with tierceron ribs and ridge rib with carved bosses.

Lincoln Cathedral – quadripartite form, with tierceron ribs and ridge rib with carved bosses.- Bremen Cathedral – north aisle, a reticular (net) vault with intersecting ribs.

Church of the Assumption, St Marein, Austria – star vault with intersecting lierne ribs.

Church of the Assumption, St Marein, Austria – star vault with intersecting lierne ribs. Salamanca Cathedral, Spain Flamboyant S-shaped and circular lierne ribs.(16th-18th century)

Salamanca Cathedral, Spain Flamboyant S-shaped and circular lierne ribs.(16th-18th century).jpg) Church of the Jacobins, Toulouse – palm tree vault

Church of the Jacobins, Toulouse – palm tree vault- Peterborough Cathedral, retrochoir – intersecting fan vaults

"Rococo Gothic" vaults of Stanislav Hall of Prague Cathedral (1493)

"Rococo Gothic" vaults of Stanislav Hall of Prague Cathedral (1493)

Columns and piers

In Early French Gothic architecture, the capitals of the columns were modeled after Roman columns of the Corinthian order, with finely-sculpted leaves. They were used in the ambulatory of the Abbey church of Saint-Denis. According to its builder, the Abbot Suger, they were inspired by the columns he had seen in the ancient baths in Rome.[17] They were used later at Sens, at Notre-Dame de Paris and at Canterbury in England.

In early Gothic churches with six-part rib vaults, the columns in the nave alternated with more massive piers to provide support for the vaults. With the introduction of the four-part rib vault, all of the piers or columns in the nave could have the same design. In the High Gothic period, a new form was introduced, composed of a central core surrounded several attached slender columns, or colonettes, going up to the vaults.[73] These clustered columns were used at Chartres, Amiens, Reims and Bourges, Westminster Abbey and Salisbury Cathedral.[74] Another variation was a quadrilobe column, shaped like a clover, formed of four attached columns.[74] In England, the clustered columns were often ornamented with stone rings, as well as columns with carved leaves.[73]

Later styles added further variations. Sometimes the piers were rectangular and fluted, as at Seville Cathedral, In England, parts of columns sometimes had contrasting colours, using combining white stone with dark Purbeck marble. In place of the Corinthian capital, some columns used a stiff-leaf design. In later Gothic, the piers became much taller, reaching up more than half of the nave. Another variation, particularly popular in eastern France, was a column without a capital, which continued upward without capitals or other interruption, all the way to the vaults, giving a dramatic display of verticality.[74]

Early Gothic - Alternating columns and piers Sens Cathedral, 12th c.)

Early Gothic - Alternating columns and piers Sens Cathedral, 12th c.) High Gothic - Clustered columns of Reims Cathedral (13th c.)

High Gothic - Clustered columns of Reims Cathedral (13th c.) Early English Gothic - Clustered columns in Salisbury Cathedral (13th century)

Early English Gothic - Clustered columns in Salisbury Cathedral (13th century) Perpendicular Gothic- columns without interruption from floor to the vaults.Nave of Canterbury Cathedral (late 14th century)

Perpendicular Gothic- columns without interruption from floor to the vaults.Nave of Canterbury Cathedral (late 14th century)

Flying buttresses

An important feature of Gothic architecture was the flying buttress, a half-arch outside the building which carried the thrust of weight of the roof or vaults inside over a roof or an aisle to a heavy stone column. The buttresses were placed in rows on either side of the building, and were often topped by heavy stone pinnacles, both to give extra weight and for additional decoration.[75]

Buttresses had existed since Roman times, usually set directly against the building, but the Gothic vaults were more sophisticated. In later structures, the buttresses often had several arches, each reaching in to a different level of the structure. The buttresses permitted the buildings to be both taller, and to have thinner walls, with greater space for windows.[75]

Over time, the buttresses and pinnacles became more elaborate supporting statues and other decoration, as at Beauvais Cathedral and Rheims Cathedral. The arches had an additional practical purpose; they contained lead channels which carried rainwater off the roof; it was expelled from the mouths of stone gargoyles placed in rows on the buttresses.[76]

Flying buttresses were used less frequently in England, where the emphasis was more on length than height. One notable example of English buttresses was Canterbury Cathedral, whose choir and buttresses were rebuilt in Gothic style by William of Sens and William the Englishman.[26] However, they were very popular in Germany: in Cologne Cathedral the buttresses were lavishly decorated with statuary and other ornament, and were a prominent feature of the exterior.

- Canterbury Cathedral with simple wall buttresses and flying buttresses (rebuilt into Gothic 1174-1177)

.jpg) East end of Lincoln Cathedral, with wall buttress, and chapter house with flying buttresses.(1185-1311)

East end of Lincoln Cathedral, with wall buttress, and chapter house with flying buttresses.(1185-1311) Flying buttresses of Notre Dame de Paris (c. 1230)

Flying buttresses of Notre Dame de Paris (c. 1230) Buttresses of Amiens Cathedral with pinnacles to give them added weight (1220-1266)

Buttresses of Amiens Cathedral with pinnacles to give them added weight (1220-1266) Section of Reims Cathedral showing the three levels of each buttress (1211-1275)

Section of Reims Cathedral showing the three levels of each buttress (1211-1275) Decorated buttresses of Cologne Cathedral (1248-1573)

Decorated buttresses of Cologne Cathedral (1248-1573)

Towers and spires

Towers, spires and fleches were an important feature of Gothic churches. They presented a dramatic spectacle of great height, helped make their churches the tallest and most visible buildings in their city, and symbolised the aspirations of their builders toward heaven.[77] They also had a practical purpose; they often served as bell towers supporting belfries, whose bells told the time by announcing religious services, warned of fire or enemy attack, and celebrated special occasions like military victories and coronations. Sometimes the bell tower is built separate from a church; the best-known example of this is the Leaning Tower of Pisa.[77]

The towers of cathedrals were usually the last part of the structure to be built. Since cathedral construction usually took many years,and was extremely expensive, by the time the tower were to be built public enthusiasm waned, and tastes changed. Many projected towers were never built, or were built in different styles than other parts of the cathedral, or with different styles on each level of the tower.[78] At Chartres Cathedral, the south tower was built in the 12th century, in the simpler Early Gothic, while the north tower is the more highly decorated Flamboyant style. Chartres would have been even more exuberant if the second plan had been followed; it called for seven towers around the transept and sanctuary.[79]

In the Ile-de-France, cathedral towers followed the Romanesque tradition of two identical towers, one on either side of the portals. The west front of the Saint-Denis, became the model for the early Gothic cathedrals and High Gothic cathedrals in northern France, including Notre-Dame de Paris, Reims Cathedral, and Amiens Cathedral.[80]

The early and High Gothic Laon Cathedral features a square lantern tower over the crossing of the transept; two towers on the western front; and two towers on the ends of the transepts. Laon's towers, with the exception of the central tower, are built with two stacked vaulted chambers pierced by lancet openings. The two western towers contain life-size stone statues of sixteen oxen in their upper arcades, said to honour the animals who hauled the stone during the cathedral's construction.[81]

In Normandy, Cathedrals and major churches often had multiple towers, built over the centuries; the Abbaye aux Hommes (begun 1066), Caen has nine towers and spires, placed on the facade, the transepts, and the centre. A lantern tower was often placed the centre of the nave, at the meeting point with the transept, to give light to the church below.

In later periods of Gothic, pointed needle-like spires were often added to the towers, giving them much greater height. A variation of the spire was the fleche, a slender, spear=like spire, which was usually placed on the transept where it crossed the nave. They were often made of wood covered with lead or other metal. They sometimes had open frames, and were decorated with sculpture. Amiens Cathedral has a notable flèche. The most famous example was that of Notre-Dame de Paris. The original flèche of Notre-Dame was built on the crossing of the transept in the middle of the 13th century, and housed five bells. It was removed in 1786 during a program to modernise the cathedral, but was put back in a new form designed by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. The new flèche, of wood covered with lead, was decorated with statues of the Apostles; the figure of St Thomas resembled Viollet-le-Duc.[82] The flèche was destroyed in the 2019 fire, but is being restored in the same design.

Oxen sculpture in High Gothic towers of Laon Cathedral (13th century)

Oxen sculpture in High Gothic towers of Laon Cathedral (13th century) Abbaye aux Hommes, Caen (tall west towers added in 13th century)

Abbaye aux Hommes, Caen (tall west towers added in 13th century) Towers of Chartres Cathedral; Flamboyant Gothic on left, early Gothic on the right.

Towers of Chartres Cathedral; Flamboyant Gothic on left, early Gothic on the right. The 13th century Flèche of Notre Dame, recreated in the 19th c, destroyed by fire in 2019, now being restored

The 13th century Flèche of Notre Dame, recreated in the 19th c, destroyed by fire in 2019, now being restored

In English Gothic, the major tower was often placed at the crossing of the transept and nave, and was much higher than the other. The most famous example is the tower of Salisbury Cathedral, completed in 1320 by William of Farleigh. It was a remarkable feat of construction, since it was built upon the pillars of the much earlier church.[83] A crossing tower was constructed at Canterbury Cathedral in 1493-1501 by John Wastell, who had previously worked on King's College at Cambridge. It was finished by Henry Yevele, who also built the present nave of Canterbury.[84] The new central tower at Wells Cathedral caused a problem; it was too heavy for the original structure. An unusual double arch had to be constructed in the centre of the crossing to give the tower the extra support it needed.[83]

England's Gothic parish churches and collegiate churches generally have a single western tower. A number of the finest churches have masonry spires, with those of St James Church, Louth; St Wulfram's Church, Grantham; St Mary Redcliffe in Bristol; and Coventry Cathedral. These spires all exceed 85 m (280 ft) in height.[85]

Westminster Abbey's crossing tower has for centuries remained unbuilt, and numerous architects have proposed various ways of completing it since the 1250s, when work began on the tower under Henry III.[86] A century and half later, an octagonal roof lantern resembling that of Ely Cathedral was installed instead, which was then demolished in the 16th century.[86] Construction began again in 1724 to the design of Nicholas Hawksmoor, after first Christopher Wren had proposed a design in 1710, but stopped again in 1727. The crossing remains covered by the stub of the lantern and a 'temporary' roof.[86]

- Salisbury Cathedral tower and spire over the crossing (1320)

.jpg) West towers of York Minster, in the Perpendicular Gothic style.

West towers of York Minster, in the Perpendicular Gothic style. The perpendicular west towers of Beverley Minster (c. 1400)

The perpendicular west towers of Beverley Minster (c. 1400)- Crossing tower of Canterbury Cathedral (1493-1505)

Later Gothic towers in Central Europe often followed the French model, but added even denser decorative tracery. Cologne Cathedral had been started in the 13th century, following the plan of Amiens Cathedral, but only the apse and the base of one tower were finished in the Gothic period. The original plans were conserved and rediscovered in 1817, and the building was completed in the 20th century following the origin design. It has two spectacularly ornamented towers, covered with arches, gables, pinancles and openwork spires pointing upwards. The tower of Ulm Minster has a similar history, begun in 1377, stopped in 1543, and not completed until the 19th century.[87]

Cologne Cathedral towers (begun 13th century, completed 20th century

Cologne Cathedral towers (begun 13th century, completed 20th century Tower of Ulm Minster (begun 1377, completed 19th century)

Tower of Ulm Minster (begun 1377, completed 19th century) Tower of Freiburg Minster (begun 1340) noted for its lacelike openwork spire

Tower of Freiburg Minster (begun 1340) noted for its lacelike openwork spire Prague Cathedral (begun 1344)

Prague Cathedral (begun 1344)

Regional variants of Gothic towers appeared in Spain and Italy. The tower of Seville Cathedral, called the Giralda, was part of what was then the largest cathedral in Europe. Burgos Cathedral was more inspired by Northern Europe. It has an exceptional cluster of openwork spires, towers, and pinnacles, drenched with ornament. It was begun in 1444 by a German architect, Juan de Colonia (John of Cologne) and eventually completed by a central tower (1540) built by his grandson.[88]

In Italy the towers were sometimes separate from the cathedral; and the architects usually kept their distance from the Northern European style. the leaning tower of Pisa Cathedral, built between 1173 and 1372, is the best-known example. The Campanile of Florence Cathedral was built by Giotto in the Florentine Gothic style, decorated with encrustations of polychrome marble. It was originally designed to have a spire.[84]

The Giralda, the bell tower of Seville Cathedral (1401-1506)

The Giralda, the bell tower of Seville Cathedral (1401-1506) Towers of Burgos Cathedral (1444-1540)

Towers of Burgos Cathedral (1444-1540) Giotto's Campanile of Florence Cathedral (1334-1359)

Giotto's Campanile of Florence Cathedral (1334-1359)

Tracery

%2C_cath%C3%A9drale_Saint-Pierre%2C_croisillon_sud%2C_parties_hautes_2.jpg)

Tracery is an architectural solution by which windows (or screens, panels, and vaults) are divided into sections of various proportions by stone bars or ribs of moulding.[89] Pointed arch windows of Gothic buildings were initially (late 12th–late 13th centuries) lancet windows, a solution typical of the Early Gothic or First Pointed style and of the Early English Gothic.[89][1] Plate tracery was the first type of tracery to be developed, emerging in the later phase of Early Gothic or First Pointed.[89] Second Pointed is distinguished from First by the appearance of bar–tracery, allowing the construction of much larger window openings, and the development of Curvilinear, Flowing, and Reticulated tracery, ultimately contributing to the Flamboyant style.[1] Late Gothic in most of Europe saw tracery patterns resembling lace develop, while in England Perpendicular Gothic or Third Pointed preferred plainer vertical mullions and transoms.[1] Tracery is practical as well as decorative, because the increasingly large windows of Gothic buildings needed maximum support against the wind.[90]

Plate tracery, in which lights were pierced in a thin wall of ashlar, allowed a window arch to have more than one light – typically two side-by-side and separated by flat stone spandrels.[89] The spandrels were then sculpted into figures like a roundel or a quatrefoil.[89] Plate tracery reached the height of its sophistication with the 12th century windows of Chartres Cathedral and in the "Dean's Eye" rose window at Lincoln Cathedral.[90]

At the beginning of the 13th century, plate tracery was superseded by bar-tracery.[89] Bar-tracery divides the large lights from one another with moulded mullions.[89] Stone bar-tracery, an important decorative element of Gothic styles, first was used at Reims Cathedral shortly after 1211, in the chevet built by Jean D'Orbais.[91] It was employed in England around 1240.[89] After 1220, master builders in England had begun to treat the window openings as a series of openings divided by thin stone bars, while before 1230 the apse chapels of Reims Cathedral were decorated with bar-tracery with cusped circles (with bars radiating from the centre).[90] Bar-tracery became common after c.1240, with increasing complexity and decreasing weight.[90] The lines of the mullions continued beyond the tops of the window lights and subdivided the open spandrels above the lights into a variety of decorative shapes.[89] Rayonnant style (c.1230–c.1350) was enabled by the development of bar-tracery in Continental Europe and is named for the radiation of lights around a central point in circular rose windows.[89] Rayonnant also deployed mouldings of two different types in tracery, where earlier styles had used moulding of a single size, with different sizes of mullions.[90] The rose windows of Notre-Dame de Paris (c.1270) are typical.[90]

The early phase of Middle Pointed style (late 13th century) is characterized by Geometrical tracery – simple bar-tracery forming patterns of foiled arches and circles interspersed with triangular lights.[89] The mullions of Geometrical style typically had capitals with curved bars emerging from them. Intersecting bar-tracery (c.1300) deployed mullions without capitals which branched off equidistant to the window-head.[89] The window-heads themselves were formed of equal curves forming a pointed arch and the tracery-bars were curved by drawing curves with differing radii from the same centres as the window-heads.[89] The mullions were in consequence branched into Y-shaped designs further ornamented with cusps. The intersecting branches produced an array of lozenge-shaped lights in between numerous lancet arched lights.Y-tracery was often employed in two-light windows c.1300.[89]

Second Pointed (14th century) saw Intersecting tracery elaborated with ogees, creating a complex reticular (net-like) design known as Reticulated tracery.[89] Second Pointed architecture deployed tracery in highly decorated fashion known as Curvilinear and Flowing (Undulating).[89] These types of bar-tracery were developed further throughout Europe in the 15th century into the Flamboyant style, named for the characteristic flame-shaped spaces between the tracery-bars.[89] These shapes are known as daggers, fish-bladders, or mouchettes.[89]

Third Pointed or Perpendicular Gothic developed in England from the later 14th century and is typified by Rectilinear tracery (panel-tracery).[89] The mullions are often joined together by transoms and continue up their straight vertical lines to the top of the window's main arch, some branching off into lesser arches, and creating a series of panel-like lights.[89] Perpendicular strove for verticality and dispensed with the Curvilinear style's sinuous lines in favour of unbroken straight mullions from top to bottom, transected by horizontal transoms and bars.[90] Four-centred arches were used in the 15th and 16th centuries to create windows of increasing size with flatter window-heads, often filling the entire wall of the bay between each buttress.[89] The windows were themselves divided into panels of lights topped by pointed arches struck from four centres.[89] The transoms were often topped by miniature crenallations.[89] The windows at Cambridge of King's College Chapel (1446–1515) represent the heights of Perpendicular tracery.[90]

Tracery could also be found on the interior of buildings, covering the walls with overlaid tracery forming blind arcades. Tracery was also used for decorating the exterior: at Strasbourg Cathedral the west front is ornamented with elaborate bar tracery.[90]

Lancet Gothic, Ripon Minster west front (begun 1160)

Lancet Gothic, Ripon Minster west front (begun 1160) Plate tracery, Chartres Cathedral clerestory (1194–1220)

Plate tracery, Chartres Cathedral clerestory (1194–1220).jpg) Plate tracery, Lincoln Cathedral "Dean's Eye" rose window (c.1225)

Plate tracery, Lincoln Cathedral "Dean's Eye" rose window (c.1225)_crop.jpg) Geometrical Decorated Gothic, Ripon Minster east window

Geometrical Decorated Gothic, Ripon Minster east window Rayonnant rose window, Strasbourg Cathedral west front

Rayonnant rose window, Strasbourg Cathedral west front Flamboyant rose window, Amiens Cathedral west front

Flamboyant rose window, Amiens Cathedral west front- Curvilinear window, Limoges Cathedral nave

Perpendicular four-centred arch, King's College Chapel, Cambridge west front

Perpendicular four-centred arch, King's College Chapel, Cambridge west front- Early bar tracery in Soissons Cathedral (13th c.)

Bar-tracery, Lincoln Cathedral east window

Bar-tracery, Lincoln Cathedral east window- Flamboyant, Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes, west front

Blind tracery, Tours Cathedral (16th century)

Blind tracery, Tours Cathedral (16th century)

Transition from Romanesque to Gothic architecture

Elements of Romanesque and Gothic architecture compared

| # | Structural element | Romanesque | Gothic | Developments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arches | Round | Pointed | The pointed Gothic arch varied from a very sharp form, to a wide, flattened form. |

| 2 | Vaults | Barrel or groin | Ribbed | Ribbed vaults appeared in the Romanesque era and were elaborated in the Gothic era. |

| 3 | Walls | Thick, with small openings | Thinner, with large openings | Wall structure diminshed during the Gothic era to a framework of mullions supporting windows. |

| 4 | Buttresses | Wall buttresses of low projection. | Wall buttresses of high projection, and flying buttresses | Complex Gothic buttresses supported the high vaults and the walls pierced with windows |

| 5 | Windows | Round arches, sometimes paired | Pointed arches, often with tracery | Gothic windows varied from simple lancet form to ornate flamboyant patterns |

| 6 | Piers and columns | Cylindrical columns, rectangular piers | Cylindrical and clustered columns, complex piers | Columns and piers developed increasing complexity during the Gothic era |

| 7 | Gallery arcades | Two openings under an arch, paired. | Two pointed openings under a pointed arch | The Gothic gallery became increasingly complex and unified with the clerestory |

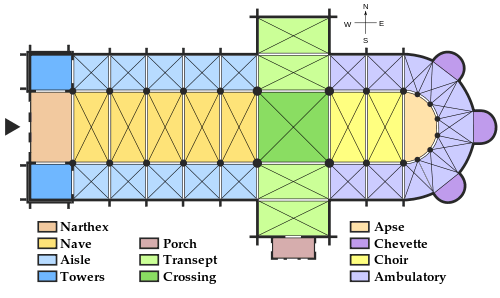

Plans

The plan of Gothic cathedrals and churches was usually based on the Latin cross (or "cruciform") plan, taken from the ancient Roman Basilica.,[92]and from the later Romanesque churches. They have a long nave making the body of the church, where the parishioners worshipped; a transverse arm called the transept and, beyond it to the east, the choir, also known as a chancel or presbytery, that was usually reserved for the clergy. The eastern end of the church was rounded in French churches, and was occupied by several radiating chapels, which allowed multiple ceremonies to go on simultaneously. In English churches the eastern end also had chapels, but was usually rectangular. A passage called the ambulatory circled the choir. This allowed parishioners, and especially pilgrims, to walk past the chapels to see the relics displayed there without disturbing other services going on.[93]

Each vault of the nave formed a separate cell, with its own supporting piers or columns. The early cathedrals, like Notre-Dame, had six=part rib vaults, with alternating columns and piers, while later cathedrals had the simpler and stronger four-part vaults, with identical columns.

Following the model of Romanesque architecture and the Basilica of Saint Denis, cathedrals usual had two towers flanking the west facade. Towers over the crossing were common in England (Salisbury Cathedral), York Minister) but rarer in France.[93]

Transepts were ususally short in early French Gothic architecture, but became longer and were given large rose windows in the Rayonnant period.[94] The choirs became more important. The choir was often flanked by a double disambulatory, which was crowned by a ring of small chapels.[94] In England, transepts were more important, and the floor plans were usually much more complex than in French cathedrals, with the addition of attached Lady Chapels, an octagonal Chapter House, and other structures (See plans of Salisbury Cathedral and York Minster below). This reflected a tendency in France to carry out multiple functions in the same space, while English cathedrals compartmentalised them. This contrast is visible in the difference between Amiens Cathedral, with its minimal transepts and semicircular apse, filled with chapels, on the east end, compared with the double transepts, projecting north porch, and rectangular east end of Salisbury and York.[95]

Elevations and the search for height

Gothic architecture was a continual search for greater height, thinner walls, and more light. This was clearly illustrated in the evolving elevations of the cathedrals.[94]

In Early Gothic architecture, following the model of the Romanesque churches, the buildings had thick, solid walls with a minimum of windows in order to give enough support for the vaulted roofs. An elevation typically had four levels. On the ground floor was an arcade with massive piers alternating with thinner columns, which supported the six-part rib vaults. Above that was a gallery, called the tribune, which provided stability to the walls, and was sometimes used to provide seating for the nuns. Above that was a narrower gallery, called the triforium, which also helped provide additional thickness and support. At the top, just beneath the vaults, was the clerestory, where the high windows were placed. The upper level was supported from the outside by the flying buttresses. This system was used at Noyon Cathedral, Sens Cathedral, and other early structures.[94]

In the High Gothic period, thanks to the introduction of the four part rib vault, a simplified elevation appeared at Chartres Cathedral and others. The alternating piers and columns on the ground floor were replaced by rows of identical circular piers wrapped in four engaged columns. The tribune disappeared, which meant that the arcades could be higher. This created more space at the top for the upper windows, which were expanded to include a smaller circular window above a group of lancet windows. The new walls gave a stronger sense of verticality and brought in more light. A similar arrangement was adapted in England, at Salisbury Cathedral, Lincoln Cathedral, and Ely Cathedral.[94]

An important characteristic of Gothic church architecture is its height, both absolute and in proportion to its width, the verticality suggesting an aspiration to Heaven. The increasing height of cathedrals over the Gothic period was accompanied by an increasing proportion of the wall devoted to windows, until, by the late Gothic, the interiors became like cages of glass. This was made possible by the development of the flying buttress, which transferred the thrust of the weight of the roof to the supports outside the walls. As a result, the walls gradually became thinner and higher, and masonry was replaced with glass. The four-part elevation of the naves of early Cathedrals such as Notre-Dame (arcade, tribune, triforium, claire-voie) was transformed in the choir of Beauvais Cathedral to very tall arcades, a thin triforium, and soaring windows up to the roof.[96]

Beauvais Cathedral reached the limit of what was possible with Gothic technology. A portion of the choir collapsed in 1284, causing alarm in all of the cities with very tall cathedrals. Panels of experts were created in Sienna and Chartres to study the stability of those structures.[97] Only the transept and choir of Beauvais were completed, and in the 21st century, the transept walls were reinforced with cross-beams. No cathedral built since exceeded the height of the choir of Beauvais.[96]

- Noyon Cathedral nave showing the four early Gothic levels (late 12h century)

- Three-part elevation of Wells Cathedral (begun 1176)

Nave of Lincoln Cathedral (begun 1185) showing three levels; arcades (bottom); tribunes (middle) and clerestory (top).

Nave of Lincoln Cathedral (begun 1185) showing three levels; arcades (bottom); tribunes (middle) and clerestory (top). Notre Dame de Paris Nave (rebuilt 1180-1220)

Notre Dame de Paris Nave (rebuilt 1180-1220) Three-part elevation of Chartres Cathedral, with larger clerestory windows.

Three-part elevation of Chartres Cathedral, with larger clerestory windows. Nave of Amiens Cathedral, looking west (1220-1270)

Nave of Amiens Cathedral, looking west (1220-1270) Nave of Strasbourg Cathedral (mid-13th century), looking east

Nave of Strasbourg Cathedral (mid-13th century), looking east- The Medieval east end of Cologne Cathedral (begun 1248)

West Front or Facade

Gothic cathedrals traditionally faced west, with the altar on the east, and the west front, or facade, was considered the most important entrance. Gothic facades were adapted from the model of the Romanesque facades.[67] The facades usually had three portals, or doorways, leading into the nave. Over each doorway was a tympanum, a work of sculpture crowded with figures. The sculpture of the central tympanum was devoted to the Last Judgement, that to the left to the Virgin Mary, and that to the right to the Saints honoured at that particular cathedral.[67] In the early Gothic, the columns of the doorways took the form of statues of saints, making them literally "pillars of the church".[67]

In the early Gothic, the facades were characterized by height, elegance, harmony, unity, and a balance of proportions.[98] They followed the doctrine expressed by Saint Thomas Aquinas that beauty was a "harmony of contrasts."[98] Following the model of Saint-Denis and later Notre-Dame de Paris, the facade was flanked by two towers proportional to the rest of the facade, which balanced the horizontal and vertical elements. Early Gothic facades often had a small rose window placed above the central portal. In England the rose window was often replaced by several lancet windows.[67]

In the High Gothic period, the facades grew higher, and had more dramatic architecture and sculpture. At Amiens Cathedral (c. 1220), the porches were deeper, the niches and pinnacles were more prominent. The portals were crowned with high arched gables, composed of concentric arches filled with sculpture. The rose windows became enormous, filling an entirely wall above the central portal, and they were themselves covered with a large pointed arch. The rose windows were pushed upwards by the growing profusion of decoration below. The towers were adorned with their own arches, often crowned with pinacles. The towers themselves were crowned with spires, often of open-work sculpture. One of the finest examples of a Flamboyant facade is Notre-Dame de l'Épine (1405-1527).[99]

While French cathedrals emphasised the height of the facade, English cathedrals, particularly in earlier Gothic, often emphasised the width. The west front of Wells Cathedral i 146 feet across, compared with 116 feet wide at the nearly contemporary Amiens Cathedral, though Amiens is twice as high. The west front of Wells was almost entirely covered with statuary, like Amiens, and was given even further emphasis by its colors; traces of blue, scarlet, and gold are found on the sculpture, as well as painted stars against the dark background on other sections.[100]

Italian Gothic facades featured the three traditional portals and rose windows, or sometimes simply a large circular window without tracery plus an abundance of flamboyant elements, including sculpture, pinnacles and spires. However, they added distinctive Italian elements. as seen in the facades of Siena Cathedral ) and of Orvieto Cathedral, The Orvieto facade was largely the work of a master mason, Lorenzo Maitani, who worked on the facade from 1308 until his death in 1330. He broke away from the French emphasis on height, and eliminated the column statutes and statuary in the arched entries, and covered the facade with colourful mosaics of biblical scenes (The current mosaics are of a later date). He also added sculpture in relief on the supporting contreforts.[101]

Another important feature of the Italian Gothic portal was the sculpted bronze door. The sculptor Andrea Pisano made the celebrated bronze doors for Florence Baptistry (1330-1336). They were not the first; Abbot Suger had commissioned bronze doors for Saint-Denis in 1140, but they were replaced with wooden doors when the Abbey was enlarged. Pisano's work, with its realism and emotion, pointed toward the coming Renaissance.[102]

Notre-Dame de Paris – deep portals, a rose window, balance of horizontal and vertical elements. Early Gothic.

Notre-Dame de Paris – deep portals, a rose window, balance of horizontal and vertical elements. Early Gothic. Wells Cathedral. (1176-1450) Early English Gothic. The facade was a Great Wall of sculpture.

Wells Cathedral. (1176-1450) Early English Gothic. The facade was a Great Wall of sculpture.- Amiens Cathedral, (13th century). Vertical emphasis. High Gothic.

.jpg) Salisbury Cathedral – wide sculptured screen, lancet windows, turrets with pinnacles.(1220-1258)

Salisbury Cathedral – wide sculptured screen, lancet windows, turrets with pinnacles.(1220-1258) Strasbourg Cathedral (1275-1486), a facade entirely covered in sculpture and tracery

Strasbourg Cathedral (1275-1486), a facade entirely covered in sculpture and tracery Brussels Cathedral, a towered highly decorated facade

Brussels Cathedral, a towered highly decorated facade- Flamboyant facade of Notre-Dame de l'Épine (1405-1527) with openwork towers

- Orvieto Cathedral (begun 1310), with polychrome mosaics

East end and the Lady Chapel

Cathedrals and churches were traditionally constructed with the altar at the east end, so that the priest and congregation congregation faced the rising sun during the morning liturgy. The sun was considered the symbol of Christ and the Second Coming, a major theme in Cathedral sculpture.[103] The portion of the church east of altar is the choir, reserved for members of the clergy. There is usually a single or double ambulatory, or aisle, around the choir and east end, so parishioners and pilgrims could walk freely easily around east end.[104]

In Romanesque churches, the east end was very dark, due to the thick walls and small windows. In the ambulatory the Basilica of Saint Denis. Abbot Suger first used the novel combination rib vaults and buttresses to replace the thick walls and replace them with stained glass, opening up that portion of the church to what he considered "divine light".[17]

In French Gothic churches, the east end, or chevet, often had an apse, a semi-circular projection with a vaulted or domed roof.[105] The chevet of large cathedrals frequently had a ring of radiating chapels, placed between the buttresses to get maximum light. There are three such chapels at Chartres Cathedral, seven at Notre Dame de Paris, Amiens Cathedral, Prague Cathedral and Cologne Cathedral, and nine at Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua in Italy. In England, the east end is more often rectangular, and gives access to a separate and large Lady Chapel, dedicated to the Virgin Mary. Lady Chapels were also common in Italy.[104]

High Gothic Chevet of Amiens Cathedral, with chapels between the buttresses (13th century)

High Gothic Chevet of Amiens Cathedral, with chapels between the buttresses (13th century).jpg) Ambulatory and Chapels of the chevet of Notre Dame de Paris (14th century)

Ambulatory and Chapels of the chevet of Notre Dame de Paris (14th century) The Henry VII Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey (begun 1503)

The Henry VII Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey (begun 1503) Ely Cathedral – square east end: Early English chancel (left) and Decorated Lady Chapel (right)

Ely Cathedral – square east end: Early English chancel (left) and Decorated Lady Chapel (right) Interior of the Ely Cathedral Lady Chapel (14th century)

Interior of the Ely Cathedral Lady Chapel (14th century)

Sculpture

Portals and Tympanum

Sculpture was an important element of Gothic architecture. Its intent was present the stories of the Bible in vivid and understandable fashion to the great majority of the faithful who could not read.[106] The iconography of the sculptural decoration on the façade was not left to the sculptors. An edict of the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 had declared: "The composition of religious images is not to be left to the inspiration of artists; it is derived from the principles put in place by the Catholic Church and religious tradition. Only the art belongs to the artist; the composition belongs to the Fathers."[106]

Monsters and devils tempting Christians - South portal of Chartres Cathedral (13th century)

Monsters and devils tempting Christians - South portal of Chartres Cathedral (13th century)- Gallery of Kings and Saints on the facade of Wells Cathedral (13th century)

Amiens Cathedral, tympanum detail -"Christ in majesty" (13th century)

Amiens Cathedral, tympanum detail -"Christ in majesty" (13th century)- Illumination of portals of Amiens Cathedral to show how it may have appeared with original colors

West portal Annunciation group at Reims Cathedral with smiling angel at left (13th century)

West portal Annunciation group at Reims Cathedral with smiling angel at left (13th century)

In Early Gothic churches, following the Romanesque tradition, sculpture appeared on the facade or west front in the triangular tympanum over the central portal. Gradually, as the style evolved, the sculpture became more and more prominent, taking over the columns of the portal, and gradually climbing above the portals, until statues in niches covered the entire facade, as in Wells Cathedral, to the transepts, and, as at Amiens Cathedral, even on the interior of the facade.[106]

Some of the earliest examples are found at Chartres Cathedral, where the three portals of the west front illustrate the three epiphanies in the Life of Christ.[107] At Amiens, the tympanum over the central portal depicted the Last Judgement, the right portal showed the Coronation of the Virgin, and the left portal showed the lives of saints who were important in the diocese. This set a pattern of complex iconography which was followed at other churches.[67]