Buddhist architecture

Buddhist religious architecture developed in the Indian subcontinent. Three types of structures are associated with the religious architecture of early Buddhism: monasteries (viharas), places to venerate relics (stupas), and shrines or prayer halls (chaityas, also called chaitya grihas), which later came to be called temples in some places.

The initial function of a stupa was the veneration and safe-guarding of the relics of Gautama Buddha. The earliest surviving example of a stupa is in Sanchi (Madhya Pradesh).

In accordance with changes in religious practice, stupas were gradually incorporated into chaitya-grihas (prayer halls). These are exemplified by the complexes of the Ajanta Caves and the Ellora Caves (Maharashtra). The Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya in Bihar is another well-known example.

The pagoda is an evolution of the Indian stupas.

.

Early development in India

A characteristic new development at Buddhist religious sites was the stupa. Stupas were originally more sculpture than building, essentially markers of some holy site or commemorating a holy man who lived there. Later forms are more elaborate and also in many cases refer back to the Mount Meru model.

One of the earliest Buddhist sites still in existence is at Sanchi, India, and this is centred on a stupa said to have been built by King Ashoka (273–236 BCE). The original simple structure is encased in a later, more decorative one, and over two centuries the whole site was elaborated upon. The four cardinal points are marked by elaborate stone gateways.

As with Buddhist art, architecture followed the spread of Buddhism throughout south and east Asia and it was the early Indian models that served as a first reference point, even though Buddhism virtually disappeared from India itself in the 10th century.

Decoration of Buddhist sites became steadily more elaborate through the last two centuries BCE, with the introduction of tablets and friezes, including human figures, particularly on stupas. However, the Buddha was not represented in human form until the 1st century CE. Instead, aniconic symbols were used. This is treated in more detail in Buddhist art, Aniconic phase. It influenced the development of temples, which eventually became a backdrop for Buddha images in most cases.

As Buddhism spread, Buddhist architecture diverged in style, reflecting the similar trends in Buddhist art. Building form was also influenced to some extent by the different forms of Buddhism in the northern countries, practising Mahayana Buddhism in the main and in the south where Theravada Buddhism prevailed.

Regional Buddhist architecture

China

When Buddhism came to China, Buddhist architecture came along with it. There were many monasteries built, equaling about 45,000. These monasteries were filled with examples of Buddhist architecture, and because of this, they hold a very prominent place in Chinese architecture. One of the earliest surviving example is the brick pagoda at the Songyue Monastery in Dengfeng County.

Indonesia

Buddhism and Hinduism reach Indonesian archipelago in early first millennia. The oldest surviving temple structure in Java is Batujaya temples in Karawang, West Java, dated as early as 5th century.[1] The temple was a Buddhist sites, as evidence of the discovered Buddhist votive tablets, and the brick stupa structure.

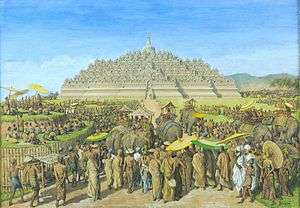

The apogee of ancient Indonesian Buddhist art and architecture was the era of Javanese Shailendra dynasty that ruled the Mataram Kingdom in Central Java circa 8th to 9th century CE. The most remarkable example is the 9th century Borobudur, a massive stupa that took form of an elaborate stepped pyramid that took plan of stone mandala. The walls and balustrades are decorated with exquisite bas reliefs, covering a total surface area of 2,500 square metres. Around the circular platforms are 72 openwork stupas, each containing a statue of the Buddha.[2] Borobudur is recognised as the largest Buddhist temple in the world.[3]

Hawaii

A lot of the Buddhist temples in Hawaii have an architecture that is very specific to the islands. This comes from the fact that the Japanese immigrants who migrated to Hawaii didn't have all the materials they would in Japan, and also the land structure was different and called for different building techniques. Because these Japanese immigrants had all the knowledge of Buddhism and were exceptional craftsmen, these temples ended up being a good personification of their religion.

There are 5 styles of architecture that can be found in the Buddhist temples of Hawaii. The styles vary because of the time periods they were used in.[4]

Converted houses

This was the earliest form of Buddhist temples in Hawaii. They took a larger plantation house and converted them into places of worship by adding things like an altar or shrines. This style offered an inexpensive way to build temples, and using residential space made the worshipers feel more connected. The most noteworthy difference is that the homes were not built with the intention of being turned into temples, they were originally built as a place for families to live. This style dropped in popularity during the 20th century.[4]

Traditional Japanese

This style originated when Japanese immigrants with the existing skill of building temples and shrines moved to Hawaii. These were made to be as similar to the original Japanese temples, but certain aspects had to be changed because of lesser access to materials and tools. Notable characteristics of this style are beam and post structure, elevated floors, and hip-and-gable roofs. The interiors held the same structure as its original counterparts in Japan.[4]

Simplified Japanese

This style originated with Japanese immigrants who did not have the greatest shrine and temple building skills. These immigrants still wanted the temples to have their original feel, but lack the skill to do it, so the building techniques they used were simplified. Some characteristics of this style are straight hip-and-gable roofs, as opposed to the long, sloping ones, separate social hall, and covered entryway. These temples doubled as community centers, and these temples were similar in style to western churches.[4]

Indian Western

This style only is unique to Hawaii and came about due to racial and religious movements. This religious movement referred to Pan-Asian Buddhism, which was a combination of Indian, Japanese, and Western Buddhism. When the first temple of this style was built, the architects that were hired had no previous experience in Buddhist architecture. This style was popular up until the 1960s. This was probably one of the most popular styles of Buddhist architecture in Hawaii; smaller temples that couldn't afford to hire architects to do this to their temple would take certain aspects of this style and apply it to their temple. The interiors of these temples are very similar to the original temples in Japan.[4]

House of worship

This style is also very similar to western churches. This style became popular in the 1960s. These temples are usually made of concrete, and the roof styles vary unlike the other styles of temples. The subcategories of this style are residential, warehouse, church, and Japanesque. Like the other styles, while the exterior is dramatically different, the interior mostly remained similar to the temples in Japan.[4]

Examples

Mahabodhi temple, Gaya

Mahabodhi temple, Gaya

- Jetavanaramaya stupa is an example of brick-clad Buddhist architecture in Sri Lanka

.jpg) Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, was built in the 1600s, is the largest monastery in India and second largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet

Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, was built in the 1600s, is the largest monastery in India and second largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet

Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim was built under the direction of Changchub Dorje, 12th Karmapa Lama in the mid-1700s[5]

Rumtek Monastery in Sikkim was built under the direction of Changchub Dorje, 12th Karmapa Lama in the mid-1700s[5]

The Rinpung Dzong follows a distinctive type of fortress architecture found in the former and present Buddhist kingdoms of the Himalayas, most notably Bhutan

The Rinpung Dzong follows a distinctive type of fortress architecture found in the former and present Buddhist kingdoms of the Himalayas, most notably Bhutan

The Great Stupa in Sanchi, India is considered a cornerstone of Buddhist architecture

The Great Stupa in Sanchi, India is considered a cornerstone of Buddhist architecture

- Mongolian statue of Avalokiteśvara (Mongolian name: Migjid Janraisig), Gandantegchinlen Monastery. Tallest indoor statue in the world, 26.5-meter-high, 1996 rebuilt, (1913)

Vatadage Temple, in Polonnaruwa, is a uniquely Sri Lankan circular shrine enclosing a small dagoba. The vatadage has a three-tiered conical roof, spanning a height of 40–50 feet, without a center post, and supported by pillars of diminishing height

Vatadage Temple, in Polonnaruwa, is a uniquely Sri Lankan circular shrine enclosing a small dagoba. The vatadage has a three-tiered conical roof, spanning a height of 40–50 feet, without a center post, and supported by pillars of diminishing height

Pagoda of Kofukuji, Nara

Pagoda of Kofukuji, Nara

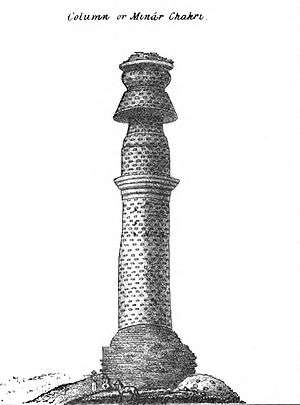

Minar-i Chakri in 1836, Afghanistan

Minar-i Chakri in 1836, Afghanistan

Shwedagon Pagoda, Myanmar

Shwedagon Pagoda, Myanmar

- Wat Phra Kaew, Bangkok, Thailand

Great Stupa at Shambhala Mountain Center, United States

Great Stupa at Shambhala Mountain Center, United States

Nan Hua Main Temple, South Africa

Nan Hua Main Temple, South Africa

Golden Temple of Shakyamuni Buddha, Kalmykia, Russian Federation

Golden Temple of Shakyamuni Buddha, Kalmykia, Russian Federation

References

- "Batujaya Temple (West Java) - Temples of Indonesia". candi.perpusnas.go.id. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Borobudur Temple Compounds". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- "Largest Buddhist temple". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- “Architecture and Interiors.” Japanese Buddhist Temples in Hawai‘i: An Illustrated Guide, by George J. Tanabe and Wills Jane Tanabe, University of Hawai'i Press, 2013, pp. 17–42. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqfvf.6.

- Achary Tsultsem Gyatso; Mullard, Saul & Tsewang Paljor (Transl.): A Short Biography of Four Tibetan Lamas and Their Activities in Sikkim, in: Bulletin of Tibetology Nr. 49, 2/2005, p. 57.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buddhist architecture. |

External links

- Peabody Essex Museum – Phillips Library: The Herbert Offen Research Collection – books and items on Buddhist architecture.