Rouen Cathedral

Rouen Cathedral (French: Cathédrale primatiale Notre-Dame de l'Assomption de Rouen) is a Roman Catholic church in Rouen, Normandy, France. It is the see of the Archbishop of Rouen, Primate of Normandy.[6] The cathedral is in the Gothic architectural tradition.[6]

| Rouen Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Rouen | |

| French: Cathédrale primatiale Notre-Dame de l'Assomption de Rouen | |

| |

| |

| Location | 3 rue Saint-Romain 76000 Rouen, Normandy France |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic Church |

| Website | rouen www |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral |

| Dedication | Assumption of Mary |

| Consecrated | 1 October 1063 in the presence of William the Conqueror[1] |

| Relics held | Saint Romain |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Yes |

| Heritage designation | Classée Monument Historique |

| Designated | 1862[2] |

| Architectural type | church |

| Style | Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1030[1] |

| Completed | 1880 |

| Specifications | |

| Number of towers | 2 |

| Number of spires | 2 |

| Bells | 70 by Paccard (64 in the Saint-Romain Tower and 6 in the Butter Tower).[3] It is the heaviest peal of bells in France (the overall weight of the cathedral's 64-bell carillon reckons at 36 tons).[4] |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Rouen |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Dominique Lebrun |

| Priest(s) | Fr.Christophe Potel |

| Laity | |

| Organist(s) | Lionel Coulon |

Building details | |

| |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1876 to 1880[I] | |

| Preceded by | St. Nicholas' Church, Hamburg |

| Surpassed by | Cologne Cathedral |

| General information | |

| Coordinates | 49.4402°N 1.0950°E |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 151 m (495 ft) |

| References | |

| [5] | |

History

A church was already present at the location in the late 4th century, and eventually a cathedral was established in Rouen as in Poitiers.[7][8] It was enlarged by St. Ouen in 650, and visited by Charlemagne in 769.

All the buildings perished during a Viking raid in the 9th century. The Viking leader, Rollo, founder of the Duchy of Normandy, was baptised here in 915 and buried in 932. His grandson, Richard I, further enlarged it in 950. St. Romain's tower was built in 1035. The buildings of Archbishop Robert II were consecrated in 1065. The cathedral was struck by lightning in 1110.

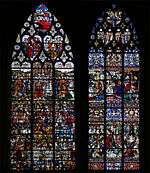

Construction on the current building began in the 12th century in Early Gothic style for Saint Romain's tower, front side porches and part of the nave. The cathedral was burnt in 1200. Others were built in High Gothic style for the mainworks: nave, transept, choir and first floor of the lantern tower in the 13th century; side chapels, lady chapel and side doorways in the 14th century. Some windows are still decorated with stained glass of the 13th century, famous because of a special cobalt blue colour, known as "the blue from Chartres". The north transept end commenced in 1280.

The cathedral was again struck by lightning in 1284. In 1302, the old Lady chapel was taken down and the new Lady chapel was built in 1360. The spire was blown down in 1353, choir windows were enlarged in 1430, the upper storey of the north-west tower was added in 1477, gable of the north transept built in 1478.

Some more parts were built in Late (Flamboyant) Gothic style, these include the last storey of Saint Romain's Tower (15th century), the Butter Tower, main porch of the front and the two storeys of the lantern tower (16th century).[9] Construction of the south-west tower began in 1485 and was finished in 1507. The Butter Tower was erected in the early 16th century. Butter was banned during Lent and those who did not wish to forgo this indulgence would donate monies of six deniers Tournois from each diocesan for this permission.[10]

The realization of the Butter Tower caused disturbances in the façade, which caused the reconstruction of the central portal and the west front, which began in 1509 and was finished in 1530. The original Gothic spire suffered a fire in 1514, nevertheless the project of a stone spire was denied and a wooden construction covered with gold-plated lead was begun in 1515, a parapet was added in 1580.

In the late 16th century the cathedral was badly damaged during the French Wars of Religion: the Calvinists damaged much of the furniture, tombs, stained-glass windows and statuary. The cathedral was again struck by lightning in 1625 and 1642, then damaged by a hurricane in 1683, the wood-work of the choir burnt in 1727 and the bell broke in 1786. In the late 18th century after the French Revolution, the state (government) nationalised the building and sold some of its furniture and statues to make money and the chapel fences were melted down to make guns to support the wars of the French Republic.

The Renaissance spire was destroyed by lightning in 1822. A new one was rebuilt in Neo-Gothic style, but of cast iron instead of wood. The cathedral was named the tallest building (the lantern tower with the cast iron spire of the 19th century) in the world (151 m) from 1876 to 1880. In the 20th century, during World War II, the cathedral was bombed in April 1944 by the British Royal Air Force. Seven bombs fell on the building, narrowly missing a key pillar of the lantern tower, but damaging much of the south aisle and destroying two rose windows. One of the bombs did not explode. A second bombing by the U.S. Army Air Force (before the Normandy Landings in June 1944) burned the oldest tower, called the North Tower or Saint-Romain Tower. During the fire the bells melted, leaving molten remains on the floor. In 1999, during Cyclone Lothar, a copper-clad wooden turret, which weighed 26 tons, broke and fell partly into the church and damaged the choir.

Musical tradition

The cathedral has had a musical tradition since the Middle Ages. Its choir was known up to the French Revolution for singing from memory. The first major organist to work there was Jean Titelouze, the so-called father of the French organ school. He occupied the post of the titular organist in 1588–1633. Around 1600 in collaboration with Franco-Flemish organ builder Crespin Carlier, Titelouze transformed the organ of the cathedral to one of the best instruments in France. Some 80 years later organ builder Robert Clicquot restored and enhanced the instrument; organists who played the new organ included composers such as Jacques Boyvin (in 1674–1706) and François d'Agincourt (1706–1758). New organs were built by Merklin & Schütze (1858–60) and, after World War II, by Jacquot-Lavergne.

In art

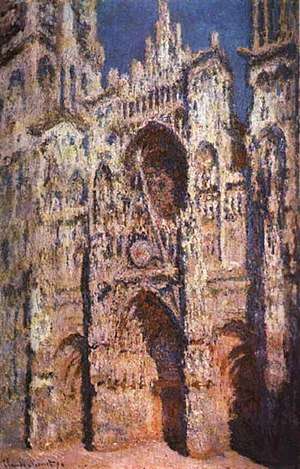

The most famous paintings of the cathedral were done by the Impressionist artist Claude Monet, who produced a series of paintings of the building showing the same scene at different times of the day and in different weather conditions. Two paintings are in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; one is in the Getty Center in Los Angeles; one is in the National Museum of Serbia in Belgrade; one is at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts; one is in a museum of Cologne; one is in the Rouen fine art museum; and five are in the musée d'Orsay in Paris. The estimated value of one painting is over $40 million. Other painters inspired by the building included John Ruskin, who selected it as an example of good architecture in The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and Roy Lichtenstein, who produced a series of pictures representing the cathedral's front. Mae Babitz, known for illustrations of the Watts Towers and Victorian era buildings in Los Angeles, illustrated the Cathedral in the 1960s. Those works are held in the UCLA library Special Collections.

Rouen Cathedral, Full Sunlight, by Claude Monet, in 1894

Rouen Cathedral, Full Sunlight, by Claude Monet, in 1894 La Cathédrale de Rouen by Claude Monet in 1893

La Cathédrale de Rouen by Claude Monet in 1893 Camille Pissarro: Rue de l’Épicerie, Rouen, in 1898

Camille Pissarro: Rue de l’Épicerie, Rouen, in 1898

In literature, Gustave Flaubert was inspired by the stained glass windows of St. Julian and the bas-relief of Salome, and based two of his Three Tales on them. Joris-Karl Huysmans wrote La Cathédrale, a novel based on an intensive examination of the building. Willa Cather sets a key scene in the development of the protagonist Claude Wheeler of One of Ours in the cathedral.

Burials

The Cathedral houses a tomb containing the heart of Richard the Lionheart. His bowels were probably buried within the church of the Château of Châlus-Chabrol in the Limousin. It was from the walls of the Château of Châlus-Chabrol that the crossbow bolt was fired, which led to his death once the wound became septic. His corporeal remains were buried next to his father at Fontevraud Abbey near Chinon and Saumur, France. Richard's effigy is on top of the tomb, and his name is inscribed in Latin on the side.

The Cathedral also contains the tomb of Rollo (Hrólfr, Rou(f) or Robert), one of Richard's ancestors, the founder and first ruler of the Viking principality in what soon became known as Normandy.

The cathedral contained the black marble tomb of John Plantagenet or John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, one of the English commanders who oversaw Joan of Arc's trial. His original tomb was destroyed by the Calvinists in the 16th century but there remains a commemorative plaque .

Other burials include:

- Maurilius, a Norman Archbishop of Rouen (d. 1067)

- Poppa, wife of Rollo of Normandy and mother of Duke William I

- William I, Duke of Normandy (also known as William Longsword)

- Hugh of Amiens, first abbot of Reading Abbey and then archbishop of Rouen

- Matilda of England (also known as the Empress Matilda)

- Walter de Coutances, medieval Anglo-Norman bishop of Lincoln and archbishop of Rouen (d. 1207)

- Hugh of Amiens (d. 1164)

- William FitzEmpress

- Arthur I, Duke of Brittany, a rival claimant to King John for the throne of England, is remembered in Rouen as he was last heard of in Rouen Castle in 1203, aged sixteen. His fate and place of burial are unknown.

- Henry the Young King

- Georges d'Amboise

- Pierre de Brézé

- Louis de Brézé, seigneur d'Anet

- Gustave Maximilien Juste de Croÿ-Solre, a French cardinal, Archbishop of Rouen, and a member of the House of Croy (d. 1844)

- Pierre Petit de Julleville (d. 1947)

- Joseph-Marie Martin, a French Cardinal and Archbishop of Rouen (d. 1976)

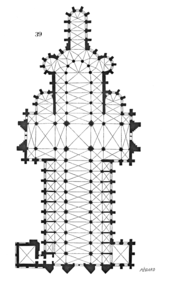

Dimensions

| Dimensions | ||

|---|---|---|

| interior length | 136.86 m | |

| exterior length | 144 m | |

| height of northern crossing | 28 m | |

| height of southern crossing | 28 m | |

| central spire | total height of spire | 151 m |

| weight of spire | 8 000 t | |

| choir | choir length | 34.30 m |

| choir height | 28 m | |

| choir width | 12.68 m | |

| crossing tower | height of crossing tower | 51 m |

| façade | width of western façade | 61.60 m |

| nave | width of nave | 24.20 m |

| length of nave | 60 m | |

| height of vaults of main aisle | 28 m | |

| height of vaults of second aisle | 14 m | |

| width of central aisle | 11.30 m | |

| tower Beurre | height | 75 m |

| tower Saint-Romain | height | 82 m |

| transept | width of transept | 24.60 m |

| exterior length of transept | 57 m | |

| interior length of transept | 53.65 m |

See also

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- List of Gothic Cathedrals in Europe

- Gothic architecture

- Church of St. Ouen, Rouen

- List of tallest churches

- André Bizette-Lindet

- Treaty of Louviers

References

- "Rouen Cathedral – Rouen, France". www.sacred-destinations.com.

- http://www.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/dapamer_fr

- "ROUEN : restauration du Carillon de la Cathédrale Notre-Dame - www.paccard.com". www.paccard.com.

- "Restaurées à Annecy, les cloches de la cathédrale seront de retour à Rouen, après Pâques".

- Rouen Cathedral at Emporis

- "Rouen Cathedral – French Moments". 26 November 2012.

- Normandy, its Gothic architecture and history: as illustrated by twenty-five photographs from buildings in Rouen, Caen, Mantes, Bayeaux, and Falaise, Frederic George Stephens, A. W. Bennett, 1865.

- bibliotheca regia Dacherius Spicilegii T. II. Coll. Concil. Labb. Tom XI. p. 1438.

- A.M. Carment-Lanfry, La cathédrale de Rouen, AMR 1977.

- Soyer, Alexis (1977) [1853]. The Pantropheon or a History of Food and its Preparation in Ancient Times. Wisbech, Cambs.: Paddington Press. p. 172. ISBN 0-448-22976-5.

Bibliography

- Aubert, Marcel (1926). "Rouen, la cathédrale", Congrès archéologique de France, LXXXIX (Rouen), 1926, 11–71.

- Carment-Lanfry, Anne-Marie (2010). La Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Rouen (in French). Rouen: Publication Univ Rouen Havre. GGKEY:LL4QAG84R2F.

- Gilbert, Antoine Pierre Marie (1816). Description historique de l'Église métropolitaine de Notre-Dame de Rouen (in French). Rouen: J. Frère.

- Heinzelmann, Dorothee (2003). Die Kathedrale Notre-Dame in Rouen – Untersuchungen zur Architektur der Normandie in früh- und hochgotischer Zeit. Rhema-Verlag, Münster 2003, ISBN 978-3-930454-21-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rouen Cathedral. |

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by St. Nicholas' Church, Hamburg |

World's tallest structure 1876–1880 151 m |

Succeeded by Cologne Cathedral |