Famagusta

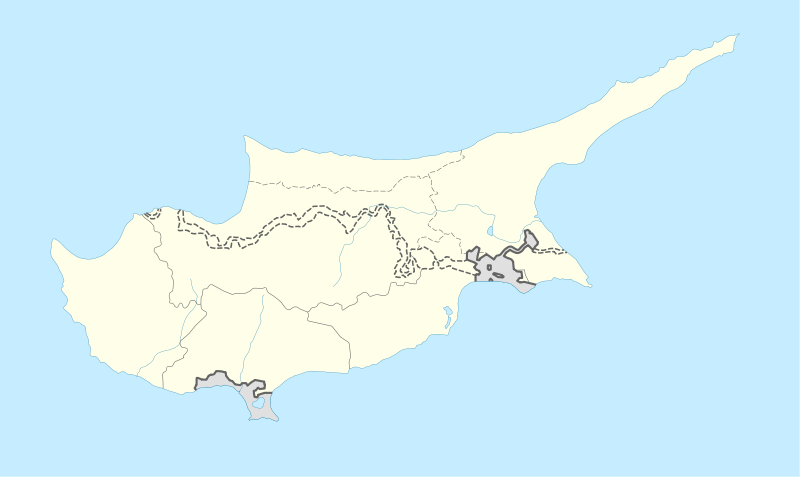

Famagusta (/ˌfæməˈɡʊstə, ˌfɑː-/; Greek: Αμμόχωστος, romanized: Ammochostos locally [aˈmːoxostos]; Turkish: Mağusa [maˈusa], or Gazimağusa [ɡaːzimaˈusa]) is a city on the east coast of Cyprus. It is located east of Nicosia and possesses the deepest harbour of the island. During the medieval period (especially under the maritime republics of Genoa and Venice), Famagusta was the island's most important port city and a gateway to trade with the ports of the Levant, from where the Silk Road merchants carried their goods to Western Europe. The old walled city and parts of the modern city presently fall within the de facto Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus in Gazimağusa District, of which it is the capital.

Famagusta | |

|---|---|

| |

Famagusta | |

| Coordinates: 35°07′30″N 33°56′30″E | |

| Country (de jure) | |

| • District | Famagusta District |

| Country (de facto) | |

| • District | Gazimağusa District |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | İsmail Arter |

| • Mayor-in-exile | Simos Ioannou |

| Population (2011)[2] | |

| • City | 40,920 |

| • Urban | 50,465 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Website | Turkish Cypriot municipality Greek Cypriot municipality |

Name

In antiquity, the town was known as Arsinoe[3] (Ancient Greek: Ἀρσινόη), after the Greek queen Arsinoe II of Egypt, and was mentioned by that name by Strabo. In Greek it is called Ammochostos (Αμμόχωστος), meaning "hidden in [the] sand". This name developed into Famagusta (originally Famagouste in French and Famagosta in Italian), used in Western European languages, and to its Turkish name, Mağusa. In Turkish, the city is also called Gazimağusa; Gazi means warrior in Turkish (ultimately from Arabic, meaning one who fights in a holy war), and the city has been officially awarded with the title after 1974 (compare Gaziantep). The old town is nicknamed "the city of 365 churches" owing to a legend that at its peak, Famagusta boasted one church for each day of the year.

History

The city was founded around 274 BC, after the serious damage to Salamis by an earthquake, by Ptolemy II Philadelphus and named "Arsinoe" after his sister.[4] Arsinoe was described as a "fishing town" by Strabo in his Geographica in the first century BC. It remained a small fishing village for a long time.[5] Later, as a result of the gradual evacuation of Salamis due to the Arab invasion led by Muawiyah I, it developed into a small port.

Medieval Famagusta

The turning point for Famagusta was 1192 with the onset of Lusignan rule. It was during this period that Famagusta developed as a fully-fledged town. It increased in importance to the Eastern Mediterranean due to its natural harbour and the walls that protected its inner town. Its population began to increase. This development accelerated in the 13th century as the town became a centre of commerce for both the East and West. An influx of Christian refugees fleeing the downfall of Acre (1291) in Palestine transformed it from a tiny village into one of the richest cities in Christendom.

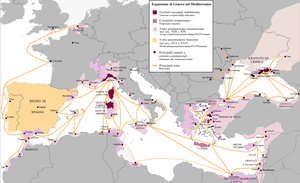

In 1372 the port was seized by Genoa and in 1489 by Venice. This commercial activity turned Famagusta into a place where merchants and ship owners led lives of luxury. The belief that people's wealth could be measured by the churches they built inspired these merchants to have churches built in varying styles. These churches, which still exist, were the reason Famagusta came to be known as "the district of churches". The development of the town focused on the social lives of the wealthy people and was centred upon the Lusignan palace, the Cathedral, the Square and the harbour.

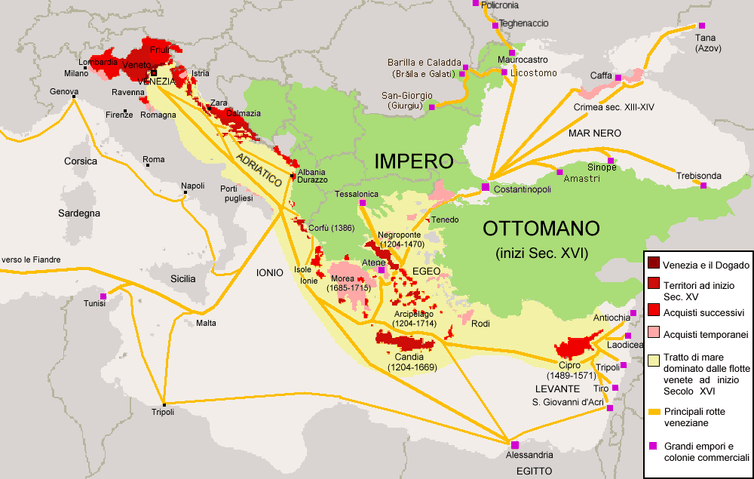

Territories, colonies and trade routes of the Republic of Genoa

Territories, colonies and trade routes of the Republic of Genoa Territories, colonies and trade routes of the Republic of Venice

Territories, colonies and trade routes of the Republic of Venice View of Famagusta in the 1480s, from Beschreibung der Reise von Konstanz nach Jerusalem

View of Famagusta in the 1480s, from Beschreibung der Reise von Konstanz nach Jerusalem

Ottoman Famagusta

In 1570–1571, Famagusta was the last stronghold in Venetian Cyprus to hold out against the Turks under Mustafa Pasha. It resisted a siege of thirteen months and a terrible bombardment, until at last the garrison surrendered. The Ottoman forces had lost 50,000 men, including Mustafa Pasha's son. Although the surrender terms had stipulated that the Venetian forces be allowed to return home, the Venetian commander, Marco Antonio Bragadin, was flayed alive, his lieutenant Tiepolo was hanged, and many other Christians were killed.[6]

With the advent of the Ottoman rule, Latins lost their privileged status in Famagusta and were expelled from the city. Greek Cypriots were at first allowed to own and buy property in the city, but were banished from the walled city in 1573-74 and had to settle outside in the area that later developed into Varosha. Turkish families from Anatolia were resettled in the walled city but could not fill the buildings that previously hosted a population of 10,000.[7] This caused a drastic decrease in the population of Famagusta. Merchants from Famagusta, who mostly consisted of Latins that had been expelled, resettled in Larnaca and as Larnaca flourished, Famagusta lost its importance as a trade centre.[8] Over time, Varosha developed into a prosperous agricultural town thanks to its location away from the marshes, whilst the walled city remained dilapidated.[7]

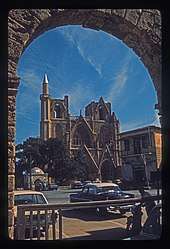

In the walled city, some buildings were repurposed to serve the interests of the Muslim population: the Cathedral of St. Nicholas was converted to a mosque (now known as Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque), a bazaar was developed, public baths, fountains and a theological school were built to accommodate the inhabitants' needs. Dead end streets, an Ottoman urban characteristic, was imported to the city and a communal spirit developed in which a small number of two-storey houses inhabited by the small upper class co-existed with the widespread one-storey houses.[9]

British rule

With the British takeover, Famagusta regained its significance as a port and an economic centre and its development was specifically targeted in British plans. As soon as the British took over the island, a Famagusta Development Act was passed that aimed at the reconstruction and redevelopment of the city's streets and dilapidated buildings as well as better hygiene. The port was developed and expanded between 1903 and 1906 and Cyprus Government Railway, with its terminus in Famagusta, started construction in 1904. Whilst Larnaca continued to be used as the main port of the island for some time, after Famagusta's use as a military base in World War I trade significantly shifted to Famagusta.[10] The city outside the walls grew at an accelerated rate, with development being centred around Varosha.[9] Varosha became the administrative centre as the British moved their headquarters and residences there and tourism grew significantly in the last years of the British rule. Pottery and production of citrus and potatoes also significantly grew in the city outside the walls, whilst agriculture within the walled city declined to non-existence.[10] New residential areas were built to accommodate the increasing population towards the end of the British rule,[9] and by 1960, Famagusta was a modern port city[11] extending far beyond Varosha and the walled city.[10]

The British period also saw a significant demographic shift in the city. In 1881, Christians constituted 60% of the city's population whilst Muslims were at 40%. By 1960, Turkish Cypriot population had dropped to 17.5% of the overall population, whilst the Greek Cypriot population had risen to 70%.[12] The city was also the site for one of the British internment camps for nearly 50,000 Jewish survivors of the Holocaust trying to emigrate to Palestine.[11]

From independence to the Turkish invasion

From independence in 1960 to the Turkish invasion of Cyprus of 1974, Famagusta developed toward the south west of Varosha as a tourist centre. In the late 1960s Famagusta became a well-known entertainment and tourist centre. The contribution of Famagusta to the country's economic activity by 1974 far exceeded its proportional dimensions within the country. Whilst its population was only about 7% of the total of the country, Famagusta by 1974 accounted for over 10% of the total industrial employment and production of Cyprus, concentrating mainly on light industry compatible with its activity as a tourist resort and turning out high-quality products ranging from food, beverages and tobacco to clothing, footwear, plastics, light machinery and transport equipment. It contributed 19.3% of the business units and employed 21.3% of the total number of persons engaged in commerce on the island. It acted as the main tourist destination of Cyprus, hosting 31.5% of the hotels and 45% of Cyprus' total bed capacity.[13] Varosha acted as the main touristic and business quarters.

In this period, the urbanisation of Famagusta slowed down and the development of the rural areas accelerated. Therefore, economic growth was shared between the city of Famagusta and the district, which had a balanced agricultural economy, with citrus, potatoes, tobacco and wheat as main products. Famagusta maintained good communications with this hinterland. The city's port remained the island's main seaport and in 1961, it was expanded to double its capacity in order to accommodate the growing volume of exports and imports. The port handled 42.7% of Cypriot exports, 48.6% of imports and 49% of passenger traffic.[14]

There has not been an official census since 1960 but the population of the town in 1974 was estimated to be around 39,000[15] not counting about 12,000–15,000 persons commuting daily from the surrounding villages and suburbs to work in Famagusta. The number of people staying in the city would swell to about 90,000–100,000 during the peak summer tourist period, with the influx of tourists from numerous European countries, mainly Britain, France, Germany and the Scandinavian countries. The majority of the city population were Greek Cypriots (26,500), with 8,500 Turkish Cypriots and 4,000 people from other ethnic groups.[15]

From the Turkish invasion to the present

During the second phase of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus on 14 August 1974 the Mesaoria plain was overrun by Turkish tanks and Famagusta was bombed by Turkish aircraft. It took two days for the Turkish Army to occupy the city, prior to which Famagusta's entire Greek Cypriot population had fled into surrounding fields. Most of these Greek Cypriots believed that once the initial violence calmed down they would be allowed to return.

As a result of the Turkish airstrikes dozens of civilians died, including tourists.[16]

Unlike other parts of the Turkish-controlled areas of Cyprus, the Varosha suburb of Famagusta was fenced off by the Turkish Army immediately after being captured and remains fenced off today. The Greek Cypriots who had fled from Varosha were not allowed to return, and journalists are banned. The city's evolution had been stalled completely, with houses, department stores and hotels empty and looted, even to the tiles on bathroom walls.

Cityscape

Famagusta's historic city centre is surrounded by the fortifications of Famagusta, which have a roughly rectangular shape, built mainly by the Venetians in the 15th and 16th centuries, though some sections of the walls have been dated earlier times, as far as 1211.[17] Some important landmarks and visitor attractions in the old city are:[18][19][20][21]

- The Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque

- The Othello Castle

- Palazzo del Provveditore - the Venetian palace of the governor, built on the site of the former Lusignan royal palace

- St. Francis' Church

- Sinan Pasha Mosque

- Church of St. George of the Greeks

- Church of St. George of the Latins

- Twin Churches

- Nestorian Church (of St George the Exiler)

- Namık Kemal Dungeon

- Agios Ioannis Church

- Venetian House

- Akkule Masjid

- Mustafa Pasha Mosque

- Ganchvor monastery

In an October 2010 report titled Saving Our Vanishing Heritage, Global Heritage Fund listed Famagusta, a "maritime ancient city of crusader kings", among the 12 sites most "On the Verge" of irreparable loss and destruction, citing insufficient management and development pressures.[22]

Economy

Famagusta is an important commercial hub of Northern Cyprus. The main economic activities in the city are tourism, education, construction and industrial production. It has a 115-acre free port, which is the most important seaport of Northern Cyprus for travel and commerce.[23][24] The port is an important source of income and employment for the city, though its volume of trade is restricted by the embargo against Northern Cyprus. Its historical sites, including the walled city, Salamis, the Othello Castle and the St Barnabas Church, as well as the sandy beaches surrounding it make it a tourist attraction; efforts are also underway to make the city more attractive for international congresses. The Eastern Mediterranean University is also an important employer and supplies significant income and activity, as well as opportunities for the construction sector. The university also raises a qualified workforce that stimulates the city's industry and makes communications industry viable. The city has two industrial zones: the Large Industrial Zone and the Little Industrial Zone. The city is also home to a fishing port, but inadequate infrastructure of the port restricts the growth of this sector.[23] The industry in the city has traditionally been concentrated on processing agricultural products.[25]

Historically, the port was the primary source of income and employment for the city, especially right after 1974. However, it gradually lost some of its importance to the economy as the share of its employees in the population of Famagusta diminished due to various reasons.[26] However, it still is the primary port for commerce in Northern Cyprus, with more than half of ships that came to Northern Cyprus in 2013 coming to Famagusta. It is the second most popular seaport for passengers, after Kyrenia, with around 20,000 passengers using the port in 2013.[27]

Politics

The mayor-in-exile of Famagusta is Simos Ioannou.[28] İsmail Arter heads the Turkish Cypriot municipal administration of Famagusta, which remains legal as a communal-based body under the constitutional system of the Republic of Cyprus.[29] Since 1974, Greek Cypriots submitted a number of proposals within the context of bicommunal discussions for the return of Varosha to UN administration, allowing the return of its previous inhabitants, requesting also the opening of Famagusta harbour for use by both communities. Varosha would have been returned under Greek Cypriot control as part of the 2004 Annan Plan if the plan had been accepted by the Greek Cypriot voters.[30]

Culture

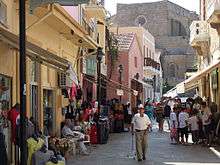

The walled city of Famagusta contains many unique buildings. Famagusta has a walled city popular with tourists.[31] Every year, the International Famagusta Art and Culture Festival is organized in Famagusta. Concerts, dance shows and theater plays take place during the festival.[32]

A growth in tourism and the city's university have fueled[33] the development of Famagusta's vibrant[34] nightlife. Nightlife in the city is especially active on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday nights and in the hotter months of the year, starting from April. Larger hotels in the city have casinos that cater to their customers.[35] Salamis Road is an area of Famagusta where bars frequented by students and locals are concentrated and is very vibrant, especially in the summer.[36]

Famagusta's Othello Castle is the setting for William Shakespeare's play Othello.[37] The city is also the setting for Victoria Hislop's 2015 novel The Sunrise,[38] and Michael Paraskos's 2016 novel In Search of Sixpence.[39] The city is the birthplace of the eponymous hero of the Renaissance proto-novel Fortunatus.

Sports

Famagusta was home to many Greek Cypriot sport teams that left the city because of the Turkish invasion and still bear their original names. Most notable football clubs originally from the city are Anorthosis Famagusta FC and Nea Salamis Famagusta FC, both of the Cypriot First Division, which are now based in Larnaca.

Famagusta is represented by Mağusa Türk Gücü in the Turkish Cypriot First Division. Dr. Fazıl Küçük Stadium is the largest football stadium in Famagusta.[40] Many Turkish Cypriot sport teams that left Southern Cyprus because of the Cypriot intercommunal violence are based in Famagusta.

Famagusta is represented by DAÜ Sports Club and Magem Sports Club in North Cyprus First Volleyball Division. Gazimağusa Türk Maarif Koleji represents Famagusta in the North Cyprus High School Volleyball League.[41]

Famagusta has a modern volleyball stadium called the Mağusa Arena.[42]

Education

The Eastern Mediterranean University was founded in the city in 1979.[43] The Istanbul Technical University founded a campus in the city in 2010.[44]

The Cyprus College of Art was founded in Famagusta by the Cypriot artist Stass Paraskos in 1969, before moving to Paphos in 1972 after protests from local hoteliers that the presence of art students in the city was putting off holidaymakers.[45]

Healthcare

Famagusta has three general hospitals. Gazimağusa Devlet Hastahanesi, a state hospital, is the biggest hospital in city. Gazimağusa Tıp Merkezi and Gazimağusa Yaşam Hastahanesi are private hospitals.

Personalities

- Chris Achilleos, illustrator of the book versions on the BBC children's series Doctor Who

- Saint Barnabas, born and died in Salamis, Famagusta

- Beran Bertuğ, Governor of Famagusta, first Cypriot woman to hold this position

- Dr. Derviş Eroğlu, former President of Northern Cyprus

- Alexis Galanos, 7th President of the House of Representatives and Cypriot Famagusta Mayor (2006-2019) (Republic of Cyprus)

- Xanthos Hadjisoteriou, Cypriot painter

- Oktay Kayalp, current Turkish Cypriot Famagusta mayor (Northern Cyprus)

- Hal Ozsan, actor (Dawson's Creek, Kyle XY)

- Oz Karahan, political activist, President of the Union of Cypriots

- Vamik Volkan, Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry

- Ṣubḥ-i-Azal, Persian religious leader, lived and died in exile in Famagusta

- George Vasiliou, former President of Cyprus

- Derviş Zaim, film director

- Touker Suleyman (born Türker Süleyman) British Turkish Cypriot fashion retail entrepreneur, investor and reality television personality.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Famagusta is twinned with:

References

- In 1983, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus unilaterally declared independence from the Republic of Cyprus. The de facto state is not recognised by any UN state except Turkey.

- KKTC 2011 Nüfus ve Konut Sayımı [TRNC 2011 Population and Housing Census] (PDF), TRNC State Planning Organization, 6 August 2013, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-06

- "ARSINOE Cyprus". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- "Brief History". Ammochostos Municipality. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- Gürkan 2008, p. 16.

- Kinross, Lord (2002). Ottoman Centuries. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-688-08093-8.

- Uluca 2006, pp. 73–5

- Gazioğlu, Ahmet C. (1990). The Turks in Cyprus: A Province of the Ottoman Empire (1571-1878). London: K. Rustem & Brother. p. 149.

- Dağlı, Uğur Ulaş. "Story of a Town". Municipality of Famagusta. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Uluca 2006, pp. 81–4

- Mirbagheri, Farid (2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. pp. 62–3. ISBN 9780810862982.

- "FAMAGUSTA/AMMOCHOSTOS". PRIO Cyprus Displacement Centre. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "Famagusta Municipality". Famagusta.org.cy. Archived from the original on 2013-05-01. Retrieved 2013-10-15.

- Cyprus Today 2010.

- Mirbagheri, Farid (2009). Historical Dictionary of Cyprus. Scarecrow Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0810862982.

- O'Malley, Brendan; Craig, Ian; Craig, Ian (2002). The Cyprus conspiracy : America, espionage, and the Turkish invasion. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 192, 216. ISBN 978-1-86064-737-6.

- Uluca 2006, p. 102

- "Gazimağusa" (PDF). TRNC Department of Tourism and. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "Tarihi Yerler" (in Turkish). Famagusta Municipality. Archived from the original on 6 May 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Dreghorn, William. "FAMAGUSTA & SALAMIS: A Guide Book". Rustem & Bro. Publishing House. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "What to see in Famagusta?". Cypnet. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Global Heritage Fund | GHF Archived August 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Ülkesel Fizik Plan - Bölüm VI. Bölge Strateji ve Politikaları (in Turkish). TRNC Department of City Planning. 2012. pp. 9–29.

- Guide to Foreign Investors (2004), TRNC State Planning Organization, p. 18-19.

- Mor, Ahmet; Çitci, M. Dursun (2006). "KUZEY KIBRIS TÜRK CUMHURİYETİ'NDE EKONOMİK ETKİNLİKLER" (PDF). Fırat University Journal of Social Science (in Turkish). 16 (1): 33–61.

- Atun, Ata. "Gazimağusa Limanının önemini kaybetme nedenleri ve kente olumlu ve olumsuz etkileri". journalacademic.com (in Turkish). Eastern Mediterranean University Famagusta Symposium of 1999. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- "KKTC Limanlarında bir yılda 2 milyon ton yük" (in Turkish). Kaptan Haber. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- "Simos Ioannou elected Mayor of Famagusta". Cyprus Mail. August 25, 2019.

- The Constitution – Appendix D: Part 12 – Miscellaneous Provisions

- Mirbagheri, Farid (2010). Historical dictionary of Cyprus ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8108-5526-7.

- Tolgay, Ahmet. Sur içi sendromu: Bir Lefkoşa – Mağusa kıyaslaması... Archived 2012-11-30 at the Wayback Machine (Kıbrıs)

- International Famagusta Art & Culture Festival (Lonely Planet) Retrieved on 2015-08-31.

- Scott, Julie (2000). Brown, Frances; Hall, Derek D.; Hall, Derek R. (eds.). Tourism in Peripheral Areas: Case Studies. Channel View Publications. p. 65. ISBN 9781873150238.

- "Mağusa geceleri capcanlı" (in Turkish). Kıbrıs. 3 May 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "Gece Hayatı" (in Turkish). Municipality of Famagusta. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "Gazimağusa" (in Turkish). Gezimanya. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "Shakespeare's 'Othello Tower,' victim of Cyprus's division, to reopen after facelift". Reuters. 17 June 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Victoria Hislop, The Sunrise (London: Headline Review 2015)

- Michael Paraskos, In Search of Sixpence (London: Friction Fiction, 2016)

- http://www.ktff.net/index.php?tpl=show_all_league&league_id=19 Archived October 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- STAR KIBRIS GAZETESİ – Şampiyonlar Gazi Mağusa’dan – Liselerarası Voleybol Birinciliği’nde kızlarda Gazi Mağusa Türk Maarif Koleji, erkeklerde Namık Kemal Lisesi rakiplerini y...

- http://gundem.emu.edu.tr/contents/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=64%3Amausa-arena-acildi&catid=44%3Aspor&Itemid=88&lang=tr Archived April 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Eastern Mediterranean University Archived 2011-04-29 at the Wayback Machine

- "Köklü ve öncü bir üniversite". Kıbrıs. 9 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Michael Paraskos, 'A Voice in the Wilderness: Stass Paraskos and the Cyprus College of Art' in The Cyprus Dossier, no. 8 (2015)

- http://www.kedke.gr/uploads/twinnedcities.pdf

- Sources

- "Famagusta: Regal Capital" (PDF). Cyprus Today. Press and Information Office, Ministry of Interior of the Republic of Cyprus. 48 (3): 5–21. 2010.

- Enlart, Camille (1899). L'art gothique et la Renaissance a Chypre. Paris, pp. 251–255.

- Magusa.org (English). Official website of Famagusta.

- Gürkan, Muzaffer Haşmet (2008). Kıbrıs'ın Sisli Tarihi (in Turkish) (1st ed.). Galeri Kültür.

- Smith, William (1854). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. s.v. Arsinoe

- Uluca, Ege (2006), Gazimağusa Kaleiçi'nin Tarihsel Süreç İçindeki Kentsel Gelişimi ve Değişimi (PhD thesis) (in Turkish), Istanbul Technical University, retrieved 4 January 2016

Further reading

- Weyl Carr, Annemarie (ed.), Famagusta, Volume 1. Art and Architecture (= Mediterranean Nexus 1100-1700. Conflict, Influence and Inspiration in the Mediterranean Area 2), Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2014. ISBN 978-2-503-54130-3

- DVD / Film: The Stones of Famagusta: the Story of a Forgotten City (2008); Allan Langdale, ″In a Contested Realm: An Illustrated Guide to the Archaeology and Historical Architecture of Northern Cyprus (2012).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Famagusta. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Famagusta. |

- Konrad von Grünenberg, complete online facsimile of Beschreibung der Reise von Konstanz nach Jerusalem.

- Famagusta City Guide

- Famagusta, 2015 NY Times feature article

- Complete online facsimile of Camile Enlart, L'art gothique et la renaissance en Chypre : illustré de 34 planches et de 421 figures, Paris, E. Leroux, 1899.