High Gothic

High Gothic is a particularly refined and imposing style of Gothic architecture that appeared in northern France from about 1195 until 1250. Notable examples include Chartres Cathedral, Reims Cathedral, Amiens Cathedral, Beauvais Cathedral, and Bourges Cathedral. It is characterized by great height, harmony, subtle and refined tracery and realistic sculpture, and by large stained glass windows, particularly rose windows and larger windows on the upper levels, which filled the interiors with light. It followed Early Gothic architecture and was succeeded by the Rayonnant style. It is often described as the high point of the Gothic style.[1]

Reims Cathedral (begun 1211) | |

| Country | France |

|---|---|

Origins

The new style illustrated the ambitions of the French kings of the Capetian dynasty, and particularly Philip II of France, who reigned from 1180 until 1223. He gradually extended his power beyond the Ile-de-France to assume dominance over Normandy, Burgundy, and Brittany. He defeated a coalition of English, German, and Flemish forces at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, making France the most powerful and prosperous state in Europe. In the process he reduced the power of the French nobles, and granted status to wealthy merchants and other bourgeoisie, who became important sponsors of Cathedrals. He founded the University of Paris, and was a great builder. He paved the Paris streets and built the first wall around the city, continued the construction of Notre Dame de Paris, and constructed the fortress of the Louvre.

The royal patronage of cathedrals and other Gothic architecture was continued Louis VIII of France and especially Louis IX of France, or Saint Louis; who paid for the transept rose windows of Notre-Dame and built Sainte-Chapelle as his royal chapel.[2][1]

Some funding for cathedrals came from the royal treasury, and from surprising foreign sources. The construction fund for Chartres Cathedral received contributions both from the French King and Richard the Lion-Hearted of England. A large part of the cost was donated by wealthy merchants and other members of community. The guilds of craftsmen also contributed, and their contributions are often indicated by small panels showing workers in those professions. Windows at Charters Cathedral have panels which illustrate and honour the shoemakers, the fishmongers, water-carriers, the vine-growers, the tanners, the masons, and furriers.[3]

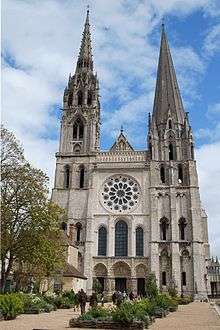

Chartres Cathedral (1194-1225)

Chartres Cathedral is in a prosperous trading town, the site of four annual trade fairs on the Feast Days of the Virgin Mary and a popular pilgrimage site which displayed the reputed tunic that Mary wore when giving birth to Christ.[4] A series of earlier cathedrals in Chartres, beginning in the fourth century, were destroyed by fire. The cathedral immediately previous to the present church burned in 1194, leaving only the crypt, towers, and the recently built west front. Rebuilding began the same year, with support from the Pope, the King, and the wealthy nobility and merchants of the city. Work was nearly completed by 1225, with the architecture, glass and sculpture finished, though the seven steeples were still being rebuilt. It was not formally reconsecrated until 1260. Only a few changes were made since that time, including the addition of a new chapel dedicated to Saint Piat in 1326, and the covering of the choir columns with stucco and the addition marble reliefs in behind the stalls in the 1750s.[5]

The new cathedral was 130.2 meters long and 30 meters high in the nave longer and higher than Notre-Dame de Paris.[6] Since the cathedral was constructed with the new flying buttresses, the walls were more stable, enabling the builders to eliminate the tribune level, and have more space for windows.[6]

The lower portions of the west front (1134-1150) are Early Gothic. The fronts of the north and south transepts are High Gothic, as is the sculpture of the six thirteenth-century portals. The spire on the north tower is later Flamboyant.[4] Chartres still has much of its original medieval stained glass, famous for the deep color called Chartres blue.[4]

- The choir of Chartres Cathedral

_08.jpg) Transept rose window of Chartres Cathedral, with "Chartres Blue" color

Transept rose window of Chartres Cathedral, with "Chartres Blue" color- South portal sculpture: "The Christian Martyrs"

Reims Cathedral (Begun 1211)

Reims Cathedral was the traditional site of the coronation of the Capetian dynasty and for that reason was given special grandeur and importance.[1] A fire in 1210 destroyed much of the old cathedral, giving an opportunity to build a more ambitious structure, The work began in 1211, but was interrupted by a local rebellion in 1233, and not resumed until 1236. The choir was finished by 1241, but work on the facade did not begin until 1252, and was not finished until the 15h century, with the completion of the bell towers.[7]

Unlike the cathedrals of Early Gothic, Reims was built with just three levels instead of four, giving greater space for windows at the top. it also used the more advanced four-part rib vault, which allowed greater height and more harmony in the nave and choir. Instead of alternating columns and piers, the vaults were supported by rounded piers, each of which was surrounded by a cluster of four attached columns which received the weight of the vaults. In addition to the large rose window on the west, smaller rose windows were added to the transepts and over the portals on the west facade, taking the place of the traditional tympanum. Another new decorative feature, blind arcade tracery, was attached to both interior walls and the facade. Even the flying buttresses were given elaborate decoration; they were crowned by small tabernacles containing statues of saints, which were topped with pinnacles, More than 2300 statues covered both the front and the back side of the facade.[7]

Main portal and side portal, with rose windows

Main portal and side portal, with rose windows- Buttresses of Reims Cathedral with pinnacles for additional weight

Amiens Cathedral (1220-1266)

Amiens Cathedral was begun in 1220 with the ambition of the builders to construct the largest cathedral in France, and they succeeded. It is 145 meters long, 70 meters wide at the transept, and has a surface area of 7700 square meters.[8] The nave was finished by 1240, and the choir built between 1241 and 1269.[8] Unusually, the names of the architects are known: Robert de Luzarches, and Thomas and Renaud Cormont. Their names and images are found in the labyrinth in the nave.[8]

The immense size of the cathedral required foundations nine meters deep. The nave has three parts and six crossings, while the choir has double collaterals, and ends in a semicircular disambulatory with seven radiating chapels. The three-level elevation of Amiens, like that of Reims, preceded Chartres Cathedral, but was notably different. The great arcades have a height of eighteen meters, equalling the combined heights of the triforium and the high windows above them. The triforium was more complex than Chartres, and had triple bays with trefoil windows, composed of two slender pointed lancet windows topped with a clover-like rose window.[8] The high windows also had a strikingly complex design; in the nave each was composed of four tall lancet windows, topped by three small roses; while in the transept the upper windows have as many as eight separate lancets.[8]

The vaults have the exceptional height of 42.4 meters. They are supported by massive piers composed of four columns, which give the nave a striking sensation of verticality. The height of the walls, particularly in the chevet, was made possible by the tall flying buttresses, making two leaps to the wall with the support of an elegant system of arches.[8]

On the exterior, the most remarkable High Gothic feature is the quality of the sculpture of the three porches, decorated altogether with fifty-two statues in their original condition. The most celebrated are on the central portal on the west, dedicated to the Last Judgement, and dominated by the statue of Christ giving a blessing which forms the central column of the doorway.[9] During the intense cleaning of the Cathedral in 1992, traces of paint were discovered indicating that all of the sculpture of the exterior was originally painted with vivid colors. This is now sometimes reproduced by projecting colored light onto the cathedral at night.[9]

Amiens Cathedral nave facing east toward choir

Amiens Cathedral nave facing east toward choir "Last Judgement" sculpture in the Tympanum of the West front

"Last Judgement" sculpture in the Tympanum of the West front

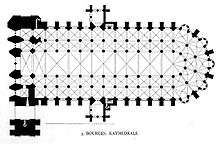

Bourges Cathedral (1195-1230)

While most High Gothic cathedrals generally followed the Chartres plan, Bourges Cathedral took a different direction. It was built by Bishop Henri de Sully, whose brother, Eudes de Sully, was the bishop of Paris, and its construction in several ways followed Notre-Dame de Paris and not Chartres. Like Chartres, the builders simplified the vertical plan to three levels; grand arcades, triforium, and high windows. The triforium was simplified a long horizontal band, the entire length of the church. However, unlike Paris, Bourges continued to use the older six-part rib vault used in Paris. This meant that the weight of the vaults fell unevenly upon the nave, and required, like Early Gothic cathedrals, alternating strong and weak pillars. This was artfully hidden by the use of large cylindrical piers, each surrounded by eight engaged colonettes. The piers of arcade are particularly imposing; each is twenty-one meters high.[10]

Since Bourges used six-part rib vaults instead of the lighter four-part vaults, the upper walls had to resist greater outward thrust, and the flying buttresses had to be more effective. The Bourges buttresses used a unique design with a particularly acute angle, which gave it the necessary force, but it was also reinforced by thicker and stronger walls than Chartres.[10]

The predominant sensation at Bourges is not only great height, but great length and interior space; the cathedral is 120 meters long, without a transept or other interruption.[11] The most unusual feature of Bourges Cathedal is the arrangement of vertical height; each part of the elevation is set back, like steps, with the highest roof and vaults over the central aisle. The outermost aisles have vaults nine meters high; the intermediate aisles have vaults 21.3 meters high; and the center aisle has vaults 37.5 meters high.[10]

Many later Gothic cathedrals followed the Chartres model, but several were influenced by Bourges, including Le Mans Cathedral, the modified Beauvais Cathedral, and Toledo Cathedral in Spain, which copied the system of vaults of different heights.[10]

Nave of Bourges Cathedral, with 21 meter high piers of the grand arcades

Nave of Bourges Cathedral, with 21 meter high piers of the grand arcades The chevet of Bourges Chathedral. Each radiating chapel has its own small sub-chapel, topped by a small spire. Double flying buttresses support the upper and middle level walls.

The chevet of Bourges Chathedral. Each radiating chapel has its own small sub-chapel, topped by a small spire. Double flying buttresses support the upper and middle level walls. Facade and west porch of Bourges Cathedral

Facade and west porch of Bourges Cathedral

Beauvais Cathedral (begun 1225)

Beauvais Cathedral in Picardy was the most ambitious and most unfortunate of High Gothic projects. Its ambition was to become the tallest of all cathedrals. The choir was built with a height of 48.5 meters (159 ft) However, due most likely to an inadequate foundation and support, the choir vaults fell in 1284. The choir was modified and rebuilt, the polygonal apse and Flamboyant transepts were finished, and in 1569 a new central tower was added, 153 meters (502 feet) high, which made Beauvais for a time the tallest structure in the world. However, in 1573 the central tower collapsed. Some parts were modified or reconstructed, but the tower was never rebuilt and the nave was never finished. Today supports are in place to stabilise the transept. Beauvais remains a majestic but unfinished piece of High Gothic architecture.[12]

Choir and transept of Beauvais Cathedral (after 1284)

Choir and transept of Beauvais Cathedral (after 1284)- Beauvais Cathedral from the east

Supports of the walls in the south transept

Supports of the walls in the south transept

Characteristics

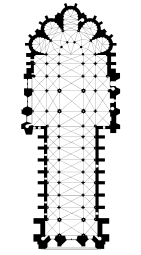

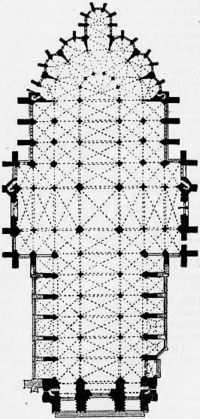

Plans

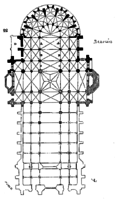

The plans of the High Gothic Cathedrals were very similar. They were extremely long and wide, with a minimal transept and maximum interior space. This made possible much larger ceremonies and the ability to welcome larger numbers of pilgrims. One curiosity of the plan of Chartres Cathedral was the floor, which slightly sloped. This was done to facilitate the cleaning of the cathedral after the departure of pilgrims who slept inside the church.[13]

Chartres Cathedral (1194-1260)

Chartres Cathedral (1194-1260) Reims Cathedral (Begun 1235)

Reims Cathedral (Begun 1235) Amiens Cathedral (1220-c. 1266)

Amiens Cathedral (1220-c. 1266) Bourges Cathedral (1195-1230)

Bourges Cathedral (1195-1230) Beauvais Cathedral (1190s-1255) (the lower portion, the nave, was never constructed)

Beauvais Cathedral (1190s-1255) (the lower portion, the nave, was never constructed)

Elevations

Thanks largely to the efficiency of the flying buttress and six-part rib vaults, All of the major High Gothic cathedrals except Bourges used the three-level elevation, eliminating the tribunes and keeping the ground floor grand gallery, the triforium, and the clerestory, or high windows. The upper windows in particular grew in size to cover almost all of the upper walls. The arcades also grew in height, occupying half the wall, so the triforium was just a narrow band.[14] The upper windows were often made of translucent grisaille glass, which allowed more light than colored stained glass.[15]

Bourges Cathedral, begun in 1195, was more complicated. It did not seek a visual unification of the nave, but rather greater diversity. The nave was taller than the side aisles, but each had three levels, which did not match. Thus the naves and aisles had separate galleries, triforia and clerestories of different heights, or five different levels in all. This same system was adapted at Le Mans Cathedral and Coutances Cathedral in France and Toledo Cathedral and Burgos Cathedral in Spain.[12]

The elevation of Chartres, with the gallery at the bottom, Triforium in the middle, and clerestory at the top.

The elevation of Chartres, with the gallery at the bottom, Triforium in the middle, and clerestory at the top.- Vaults triforia and upper windows of Amiens Cathedral.[15]

- Three-part elevation of nave of Reims Cathedral

Elevations of Bourges Cathedral. The outer aisles and nave had their own elevations, with galleries, triforia and clerestories of different heights.

Elevations of Bourges Cathedral. The outer aisles and nave had their own elevations, with galleries, triforia and clerestories of different heights.

Vaults, piers and pillars

All of the High Gothic Cathedrals except Bourges Cathedral used the newer four-part rib vault, which allowed more even weight distribution to the piers and columns in the nave. Early Gothic churches used alternating piers and columns to support the varying weight from the six-part vaults,

In 1192 Notre Dame, which had six-part vaults, had introduced a new kind of support; a central pillar surrounded by four engaged shafts. The pillars supported the gallery, while the shafts continued upwards as colonettes attached to the walls and supported the vaults. Variations of this kind of support gave greater harmony to the appearance of the nave. They frequently had capitals which were decorated with floral sculpture. They appeared at Chartres and then were found, in various forms, in all of the High Gothic Cathedrals.[14]

_03.jpg) Chartres: Four-part rib vaults connected by colonettes to pillars below

Chartres: Four-part rib vaults connected by colonettes to pillars below The massive pillars, surrounded by colonettes, and topped with floral capitals, of Reims Cathedral

The massive pillars, surrounded by colonettes, and topped with floral capitals, of Reims Cathedral_(3485934559).jpg) The very high pillars with six-part vaults of Bourges Cathedral

The very high pillars with six-part vaults of Bourges Cathedral Transept vaults and pillars of Amiens Cathedral

Transept vaults and pillars of Amiens Cathedral

Flying buttress

The flying buttress was an essential feature of High Gothic architecture; the great height and large upper windows would have been impossible without them. Buttresses with arches apart from the walls had existed in earlier periods, but they were generally small, close to the walls, and were often hidden by the outer architecture. In High Gothic, the buttresses were nearly as tall as the building itself. massive, and meant to be seen; they were decorated with pinnacles and sculpture.

Flying buttresses had been used to support the upper windows of the apse in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Pres, completed in 1063[16] and then at Notre Dame de Paris. They were then used in a more ambitious way to support the upper walls of Chartres Cathedral. The first flying buttresses of Chartres were built atop the wall abutments of the nave and choir of the earlier cathedral. They had a double arch reinforced with small columns like the spokes of a wheel. Each small column, with its base and capital, was carved from a single block of stone, Each arch had a sort of stone pyramid on top to add extra weight. Later a second set of arches was added to the nave and choir above the spoked arches, which reached longer and added greater strength.[17]

Similar buttresses were added to each of the High Gothic Cathedrals. The buttresses of each Cathedral were unique, and had its own distinct form and decoration. The buttresses of Beauvais Cathedral, the last and tallest High Gothic Cathedral, are so high and numerous that they practically hide the Cathedral.

- Flying buttresses of Chartres from above, showing the earlier spoked arch below and newer arch above

Double arches of the apse of Reims Cathedral, capped with stone pinnacles for greater weight

Double arches of the apse of Reims Cathedral, capped with stone pinnacles for greater weight Flying buttresses of Amiens Cathedral

Flying buttresses of Amiens Cathedral%2C_cath%C3%A9drale_Saint-Pierre%2C_ch%C5%93ur%2C_vue_depuis_le_sud-est.jpg) Buttresses practically conceal the choir of Beauvais Cathedral

Buttresses practically conceal the choir of Beauvais Cathedral

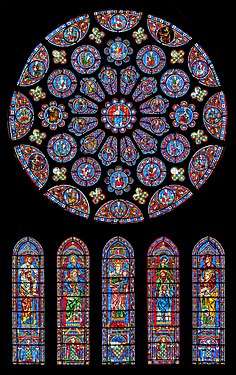

Stained glass and The Rose Window

A type of small round window, called an oculus, had been used in Romanesque churches.[18] The facade of the Basilica of Saint Denis featured an early rose window on its west front. This was made with plate tracery, where the design was formed by a group of variously shaped openings which appeared to be cut out of the wall. A more ambitious model, with the armature of a wheel made of stone mullions, appeared at Senlis Cathedral in 1200. A similar early Gothic window was constructed for the facade of Chartres Cathedral in 1215. It was soon followed by the High Gothic window of the facade of Laon Cathedral (1200-1215).[19] In 1215, the two great transept windows of Chartres Chathedral were completed. These became the model for many similar windows in France and beyond. The amount of stained glass in Chartres was unprecedented; one hundred sixty four bays, with 2,600 square meters of stained glass. A remarkably large amount of the original glass is still in place.[20]

Not long after the introduction of the High Gothic rose window, Gothic architects, fearing that the interiors of the cathedrals were too dark, began experimenting with grisaille windows, which emphasized the important figures in the windows, and also brightened the interiors. These were used at Poitiers Cathedral in 1270 and then by Chartres Cathedral around 1300. Large bands of translucent gray glass were put around the fully colored figures of Christ, The Virgin Mary, and other prominent subjects.[15]

The West rose window of Chartres Cathedral (The Last Judgement) (1215)

The West rose window of Chartres Cathedral (The Last Judgement) (1215) South rose window of Chartres Cathedral

South rose window of Chartres Cathedral Detail of "Notre-Dame de la Belle Verrière" window at Chartres Cathedral (12th century for the Virgin (against the red background), 13th century for the angels)

Detail of "Notre-Dame de la Belle Verrière" window at Chartres Cathedral (12th century for the Virgin (against the red background), 13th century for the angels) Last Judgement window of Bourges Cathedral

Last Judgement window of Bourges Cathedral- Glass in the choir of Amiens Cathedral

- West rose window of Reims Cathedral (1252-1275)

- Windows of Beauvais Cathedral

Tracery

Tracery is the term for the intricate designs of slender stone bars and ribs which were used to support the glass and to decorate rose windows and other windows and openings. It also was used increasingly on exterior and interior walls, in the form of stone ribs or molding, to create increasingly intricate forms such as blind arcades. This form was called blind tracery.[21]

The west window of Chartres Cathedral used an early form called plate tracery, a geometric pattern of openings in the stonework filled with glass. Prior to 1230, the builders of Reims Cathedral used a more sophisticated form, called bar tracery, in the apse chapel. This was a pattern of cusped circles, made with thin pointed bars of stone projecting inward.[21] This model was followed and developed in the transept windows of Chartres Cathedral, at Amiens Cathedral and the other High Gothic cathedrals. After the middle of the 13th century, the windows began to be decorated with even larger and complex designs, resembling light shining outwards, which gave the name to the Rayonnant style.[21]

- Plate tracery of the West rose window of Chartres Cathedral (1215)

- Early bar tracery at Reims Cathedral (Prior to 1230)

Sculpture

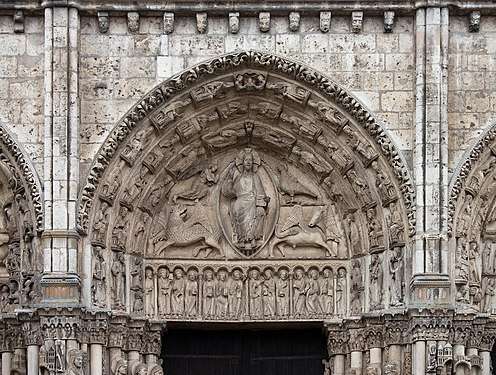

Sculpture was an integral element of High Gothic architecture. It followed upon and expanded the use of sculpture by Romanesque builders. Sculpture filled with tympanum over the central portal, occupied the columns, and was placed in niches tigher on the facade. The subjects were essentially the same on each cathedral; Saints, apostles, and Kings. At the end of the 12th century Their poses were very formal, and the faces rarely seemed to be looking at each other or at anyone else. The greatest variety was usually in their drapery, which could be highly stylised or natural. But in the 13th century the faces and figures became much more vivid and expressive.[22]

The sculpture of Chartres Cathedral served as a model for other High Gothic cathedrals. The sculpture of the west porch or royal portal is the oldest, dating to the late 12th century before the 1194 fire. The main themes are the descent of Christ to the earth; his ascension, and the apocalypse, or day of judgement, illustrated by almost two hundred small figures. The stories are not told in chronological order, but follow a certain path; they begin to the left of the central door, go to the left as far as the south tower, then continue to the right as far as the north tower. The major figure in the central tympanum is Christ, seated on a throne, rendering judgement. In addition to the tympanum sculpture, the columns also contain statues of figures from the Old Testament. Following the style of the 12th century, the bodies and costumes of the figures are practically ignored; all the skill of the sculptor is used on the expressive faces.[23]

The north porch and south porch sculpture at Chartres is from the beginning of the 13th century, and represents the more mature High Gothic style. The principal themes on the north porch are the Old Testament and the life of the Virgin Mary, along with vivid representations of the vices and the virtues. The South porch portrays the acts of Christ with his apostles, and the Christian martyrs, while above the door is a portrayal of the Last Judgement. The figures are crowded into the archivolts over the doorway, The porches also contain statues of confessors, saints, Emperors and Kings in the arcades above the portals. The thirteenth century figures are portrayed with more emotion and movement. Together, the sculptures of Chartres formed a comprehensive visual retelling of the Old and New Testament, as well as a catalog of virtues to imitate and vices to avoid.[23]

Royal portal tympanum at Chartres Cathedral (End of 12th century)

Royal portal tympanum at Chartres Cathedral (End of 12th century) Monsters and devils tempting Christians on the Chartres south portal (early 13th century)

Monsters and devils tempting Christians on the Chartres south portal (early 13th century) New Testament figures at Chartres Cathedral (early 13th century)

New Testament figures at Chartres Cathedral (early 13th century)

It is probable that some of the sculptors who made the sculpture of the transepts of Chartres travelled north to Reims, where work began in 1210, and possibly also to Amiens Cathedral, where work began 1218. Nonetheless, the sculpture of each church has its own distinct characteristics. The sculpture of Amiens shows the influence of ancient Roman sculpture, particularly in the realistically modelled drapery of their clothing. The expressions are passive, and the gestures minimal, giving a sense of calm and serenity. The sculpture of Reims showed a similar calm.[24]

An entirely different and more naturalistic style of High Gothic sculpture appeared on the west front Reims Cathedral in the 1240s. This was the work of the sculptor known as Joseph of Reims, named for the vivid smiling statue of Saint Joseph he made for the facade. He also created the Smiling Angel. This famous work was knocked off the Cathedral by a bombardment in World War I, but was carefully reassembled and is now back in its original place.[25] Reims is also noted for the Gallery of Kings, a sculptural depiction of the French Kings crowned at Reims, which begins on the facade and continues on the inside of the facade.

The vegetal decoration of the capitals of the columns of the nave were another distinctive feature of High Gothic sculpture. They were made in finely crafted vegetal forms, complete with birds and other creatures. This followed an ancient Roman model, and had been used at Saint-Denis, but at Reims they became much more realistic and detailed. As the work continued toward the west in the nave, the foliage became more abundant and filled with life. This model was copied in Gothic cathedrals first in France, and then across Europe.[26]

"The Smiling Angel" (1236-45) from Reims Cathedral

"The Smiling Angel" (1236-45) from Reims Cathedral Sculpture in the Gallery of Kings of Reims Cathedral

Sculpture in the Gallery of Kings of Reims Cathedral Central tympanum on facade of Amiens Cathedral

Central tympanum on facade of Amiens Cathedral Accurately sculpted vegetation (horse chestnuts) on the column capitals of Reims Cathedral

Accurately sculpted vegetation (horse chestnuts) on the column capitals of Reims Cathedral The highly animated Tympanum of Bourges Cathedral

The highly animated Tympanum of Bourges Cathedral Detail of Bourges Cathedral sculpture

Detail of Bourges Cathedral sculpture

References

- Watkin 1986, p. 132.

- Branner, Robert (1965). St. Louis and the Court style in Gothic architecture. London: A. Zwemmer. ISBN 0-302-02753-X.

- Houvet 2019, p. 67-75.

- Watkin 1986, p. 131.

- Houvet 2019, p. 12.

- Mignon 2015, p. 21.

- Mignon 2015, p. 26.

- Mignon 2015, p. 28.

- Mignon 2015, p. 29.

- Bony 1985, p. 212.

- Mignon 2015, p. 24.

- Watkin 1986, p. 135.

- Houvet 2019, p. 23.

- Ducher 2014, p. 42.

- Chastel 2000, p. 146.

- Mignon 2015, p. 19.

- Houvet 2019, p. 20.

- O'Reilly 1921, Chapter one, Loc. 2607 (Project Gutenberg text).

- Chastel 2000, p. 144-146.

- Chastel 2000, p. 129.

- "Tracery". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- Martindale 1993, p. 40-51.

- Houvet (2019), p. 32-33.

- Martindale 1993, p. 48.

- Martindale 1993, p. 50-51.

- Martindale 1993, p. 51.

Bibliography

In English

- Bony, Jean (1985). French Gothic Architecture of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05586-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Houvet, E (2019). Miller, Malcolm B (ed.). Chartres - Guide of the Cathedral. Éditions Houvet. ISBN 2-909575-65-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martindale, Andrew (1993). Gothic Art. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-2-87811-058-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Reilly, Elizabeth Boyle (1921). How France Built Her Cathedrals - A study in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Harper and Brothers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

In French

- Chastel, André (2000). L'Art Français Pré-Moyen Âge Moyen Âge (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-012298-3.

- Ducher, Robert (2014). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-0813-4383-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mignon, Olivier (2015). Architecture des Cathédrales Gothiques (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-6535-5.

- Renault, Christophe and Lazé, Christophe, Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier, (2006), Gisserot, (in French); ISBN 9-782877-474658

- Wenzler, Claude (2018), Cathédales Gothiques - un Défi Médiéval, Éditions Ouest-France, Rennes (in French) ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9

- Le Guide du Patrimoine en France (2002), Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux (in French) ISBN 978-2-85822-760-0

.jpg)