Chaldean Catholic Church

The Chaldean Catholic Church (Classical Syriac: ܥܕܬܐ ܟܠܕܝܬܐ ܩܬܘܠܝܩܝܬܐ, ʿīdtha kaldetha qāthuliqetha; Arabic: الكنيسة الكلدانية al-Kanīsa al-kaldāniyya; Latin: Ecclesia Chaldaeorum Catholica, lit. 'Catholic Church of the Chaldeans') is an Eastern Catholic particular church (sui juris) in full communion with the Holy See and the rest of the Catholic Church, and is headed by the Chaldean Catholic Patriarch of Babylon. Employing in its liturgy the East Syriac Rite in the Syriac language, it is part of Syriac Christianity. Headquartered in the Cathedral of Mary Mother of Sorrows, Baghdad, Iraq, since 1950, it is headed by the Catholicos-Patriarch Louis Raphaël I Sako. In 2010, it had a membership of 490,371, of whom 310,235 (63.27%) lived in the Middle East (mainly in Iraq).[5]

Chaldean Catholic Church | |

|---|---|

| Classical Syriac: ܥܕܬܐ ܟܠܕܝܬܐ ܩܬܘܠܝܩܝܬܐ | |

| Classification | Eastern Catholic |

| Orientation | Syriac Christianity (Eastern) |

| Scripture | Peshitta[1] |

| Theology | Catholic theology |

| Governance | Holy Synod of the Chaldean Church[2] |

| Pope | Francis |

| Patriarch | Louis Raphaël I Sako |

| Region | Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Syria, with diaspora |

| Language | Liturgical: Syriac[3] |

| Liturgy | East Syriac Rite |

| Headquarters | Cathedral of Mary Mother of Sorrows, Baghdad, Iraq |

| Founder | Traces ultimate origins to Thomas the Apostle and the Apostolic Era through Addai and Mari |

| Origin | 1552 |

| Separations | Assyrian Church of the East (1692) |

| Members | 616,639 (2018)[4] |

| Other name(s) | Chaldean Patriarchate |

| Official website | www |

| Part of a series on |

| Particular churches sui iuris of the Catholic Church |

|---|

Latin cross and Byzantine Patriarchal cross |

| Particular churches are grouped by rite. |

| Alexandrian Rite |

| Armenian Rite |

| Byzantine Rite |

| East Syriac Rite |

| Latin liturgical rites |

| West Syriac Rite |

|

|

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, reports that, according to the Iraqi Christian Foundation, an agency of the Chaldean Catholic Church, approximately 80% of Iraqi Christians are of that Church.[6] In its own 2018 Report on Religious Freedom, the U.S. Department of State put the Chaldean Catholics at approximately 67% of the Christians in Iraq.[7] The 2019 Country Guidance on Iraq of the European Asylum Support Office gives the same information as the U.S. Department of State.[8]

Origin

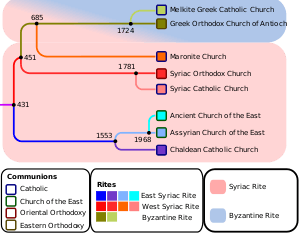

The Chaldean Catholic Church arose following a schism within the Church of the East. In 1552 the established "Eliya line" of patriarchs was opposed by a rival patriarch, Sulaqa, who initiated what is called the "Shimun line". He and his early successors entered into communion with the Catholic Church, but in the course of over a century loosened their link with Rome and under Shimun XIII Dinkha openly renounced it in 1672 by adopting a profession of faith that contradicted that of Rome, while they maintained their independence from the "Eliya line". Leadership of those who wished to be in communion with Rome then passed to the Archbishop of Amid Joseph I, recognized as Catholic patriarch first by the Turkish civil authorities (1677) and then by Rome itself (1681). A century and a half later, in 1830, Rome conferred headship of the Catholics on Yohannan Hormizd. A member of the "Eliya line" family: he opposed Ishoyahb (1778–1804) the last of that line to be elected in the normal way as patriarch, was himself irregularly elected in 1780, as Sulaqa had been in 1552, and won over to communion with Rome most of the followers of the Eliya line. The "Shimun line" that in 1553 entered communion with Rome and broke it off in 1672 is now that of the church that in 1976 officially adopted the name "Assyrian Church of the East",[9][10][11][12] while a member of the "Eliya line" family is part of the series of patriarchs of the Chaldean Catholic Church.

The description "Chaldean"

For many centuries, from at least the time of Jerome (c. 347 – 420),[13] the term "Chaldean" indicated the Aramaic language and was still the normal name in the nineteenth century.[14][15][16] Only in 1445 did it begin to be used to mean Aramaic speakers in communion with the Catholic Church, on the basis of a decree of the Council of Florence,[17] which accepted the profession of faith that Timothy, metropolitan of the Aramaic speakers in Cyprus, made in Aramaic, and which decreed that "nobody shall in future dare to call [...] Chaldeans, Nestorians".[18][19][20] Previously, when there were as yet no Catholic Aramaic speakers of Mesopotamian origin, the term "Chaldean" was applied with explicit reference to their "Nestorian" religion. Thus Jacques de Vitry wrote of them in 1220/1 that "they denied that Mary was the Mother of God and claimed that Christ existed in two persons. They consecrated leavened bread and used the 'Chaldean' (Syriac) language".[21] The decree of the Council of Florence was directed against use of "Chaldean" to signify "non-Catholic"

Outside of Catholic Church usage, the term "Chaldean" continued to apply to all associated with the Church of the East tradition, whether they were in communion with Rome or not. It indicated not race or nationality, but only language or religion. Throughout the 19th century it continued to be used of East Syriac Christians, whether "Nestorian" or Catholic,[22][23][24][25][26] and this usage continued into the 20th century.[27] In 1852 George Percy Badger distinguished those whom he called Chaldeans from those whom he called Nestorians, but by religion alone, never by language, race or nationality.[28]

Patriarch Raphael I Bidawid of the Chaldean Catholic Church (1989–2003), who accepted the term "Assyrian" as descriptive of his nationality, commented: "When a portion of the Church of the East became Catholic in the 17th Century, the name given to the church was 'Chaldean' based on the Magi kings who were believed by some to have come from what once had been the land of the Chaldean, to Bethlehem. The name 'Chaldean' does not represent an ethnicity, just a church [...] We have to separate what is ethnicity and what is religion [...] I myself, my sect is Chaldean, but ethnically, I am Assyrian."[29] Earlier, he said: "Before I became a priest I was an Assyrian, before I became a bishop I was an Assyrian, I am an Assyrian today, tomorrow, forever, and I am proud of it."[30]

History

The Church of the East

The Chaldean Catholic Church traces its beginnings to the Church of the East, which was founded in the Parthian Empire. The Acts of the Apostles mentions Parthians as among those to whom the apostles preached on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:9. Thomas the Apostle, Thaddeus of Edessa, and Bartholomew the Apostle are reputed to ber its founders. One of the modern Churches that boast descent from it says it is "the Church in Babylon" spoken of in 1 Peter 5:13 and that he visited it.[31]

Under the rule of the Sasanian Empire, which overthrew the Parthians in 224, the Church of the East continued to develop its distinctive identity by use of the Syriac language and Syriac script. One "Persian" bishop was at the First Council of Nicaea (325).[32] There is no mention of Persian participation in the First Council of Constantinople (381), in which also the Western part of the Roman Empire was not involved.

The Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon of 410, held in the Sasanian capital, recognized the city's bishop Isaac as Catholicos, with authority throughout the Church of the East. The persistent military conflicts between the Sasanians and the by then Christianized Roman Empire made the Persians suspect the Church of the East of sympathizing with the enemy. This in turn induced the Church of the East to distance itself increasingly from that in the Roman Empire. Although in a time of peace their 420 council explicitly accepted the decrees of some "western" councils, including that of Nicaea, in 424 they determined that thenceforth they would refer disciplinary or theological problems to no external power, especially not to any "western" bishop or council.[33][34]

The theological controversy that followed the Council of Ephesus in 431 was a turning point in the history of the Church of the East. The Council condemned as heretical the Christology of Nestorius, whose reluctance to accord the Virgin Mary the title Theotokos "God-bearer, Mother of God" was taken as evidence that he believed two separate persons (as opposed to two united natures) to be present within Christ. The Sasanian Emperor provided refuge for those who in the Nestorian Schism rejected the decrees of the Council of Ephesus enforced in the Byzantine Empire.[35] In 484 he executed the pro-Roman Catholicos Babowai. Under the influence of Barsauma, Bishop of Nisibis, the Church of the East officially accepted as normative the teaching not of Nestorius himself, but of his teacher Theodore of Mopsuestia, whose writings the 553 Second Council of Constantinople condemned as Nestorian but some modern scholars view them as orthodox.[36] The position thus assigned to Theodore in the Church of the East was reinforced in several subsequent synods in spite of the opposing teaching of Henana of Adiabeme.[37]

After its split with the West and its adoption of a theology that some called Nestorianism, the Church of the East expanded rapidly in the medieval period due to missionary work. Between 500 and 1400 its geographical horizon extended well beyond its heartland in present-day northern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, setting up communities throughout Central Asia and as far as China as witnessed by the Nestorian Stele, a Tang dynasty tablet in Chinese script dating to 781 that documented 150 years of Christian history in China.[38] Their most lasting addition was of the Saint Thomas Christians of the Malabar Coast in India, where they had around 10 million followers.[39]

However, a decline had already set in at the time of Yahballaha III (1281–1317), when the Church of the East reached its greatest geographical extent, it had in south and central Iraq and in south, central and east Persia only four dioceses, where at the end of the ninth century it had at least 54,[40] and Yahballaha himself died at the hands of a Muslim mob.

Around 1400, the Turco-Mongol nomadic conqueror Timur arose out of the Eurasian Steppe to lead military campaigns across Western, Southern and Central Asia, ultimately seizing much of the Muslim world after defeating the Mamluks of Egypt and Syria, the emerging Ottoman Empire, and the declining Delhi Sultanate. Timur's conquests devastated most Assyrian bishoprics and destroyed the 4000-year-old cultural and religious capital of Assur. After the destruction brought on by Timur, the massive and organized Nestorian Church structure was largely reduced to its region of origin, with the exception of the Saint Thomas Christians in India.

1552 schism

The Church of the East has seen many disputes about the position of Catholicos. A synod in 539 decided that neither of the two claimants, Elisha and Narsai, who had been elected by rival groups of bishops in 524, was legitimate.[41] Similar conflicts occurred between Barsauma and Acacius of Seleucia-Ctesiphon and between Hnanisho I and Yohannan the Leper. The 1552 conflict was not merely between two individuals but extended to two rival lines of patriarchs, like the 1964 schism between what are now called the Assyrian and the Ancient Church of the East.

Dissent over the practice of hereditary succession to the Patriarchate (usually from uncle to nephew) led to the action in 1552 by a group of bishops from the northern regions of Amid and Salmas who elected as a rival Patriarch the abbot of Rabban Hormizd Monastery (which was the Patriarch's residence) Yohannan Sulaqa. "To strengthen the position of their candidate the bishops sent him to Rome to negotiate a new union".[42] By tradition, a patriarch could be ordained only by someone of archiepiscopal (metropolitan) rank, a rank to which only members of that one family were promoted. So Sulaqa travelled to Rome, where, presented as the new patriarch elect, he entered communion with the Catholic Church and was ordained by the Pope and recognized as patriarch. The title or description under which he was recognized as patriarch is given variously as "Patriarch of Mosul in Eastern Syria";[43] "Patriarch of the Church of the Chaldeans of Mosul";[44] "Patriarch of the Chaldeans";[42][45][46] "patriarch of Mosul";[47][48][49] or "patriarch of the Eastern Assyrians", this last being the version given by Pietro Strozzi on the second-last unnumbered page before page 1 of his De Dogmatibus Chaldaeorum,[50] of which an English translation is given in Adrian Fortescue's Lesser Eastern Churches.[51][52] The "Eastern Assyrians", who, if not Catholic, were presumed to be Nestorians, were distinguished from the "Western Assyrians" (those west of the Tigris River), who were looked on as Jacobites.[53][54][55] It was as Patriarch of the "Eastern Assyrians" that Sulaqa's successor, Abdisho IV Maron, was accredited for participation in the Council of Trent.[56]

The names already in use (except that of "Nestorian") were thus applied to the existing church (not a new one) for which the request to consecrate its patriarch was made by emissaries who gave the impression that the patriarchal see was vacant.[48][57][58]

Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa returned home in the same year and, unable to take possession of the traditional patriarchal seat near Alqosh, resided in Amid. Before being put to death at the instigation of the partisans of the Patriarch from whom he had broken away[59], he ordained two metropolitans and three other bishops,[57][48] thus initiating a new ecclesiastical hierarchy under what is known as the "Shimun line" of patriarchs, who soon moved from Amid eastward, settling, after many intervening places, in the isolated village of Qochanis under Persian rule.

Successive leaders of those in communion with Rome

Sulaqa's earliest successors entered into communion with the Catholic Church, but in the course of over a century their link with Rome grew weak. The last to request and obtain formal papal recognition died in 1600. They adopted hereditary succession to the patriarchate, opposition to which had caused the 1552 schism. In 1672, Shimun XIII Dinkha formally broke communion with Rome, adopting a profession of faith that contradicted that of Rome, while he maintained his independence from the Alqosh-based "Eliya line" of patriarchs. The "Shimun line" eventually became the patriarchal line of what since 1976 is officially called the Assyrian Church of the East.[60][61][62][63]

Leadership of those who wished to be in communion with Rome then passed to Archbishop Joseph of Amid. In 1677 his leadership was recognized first by the Turkish civil authorities, and then in 1681 by Rome. (Until then, the authority of the Alqosh patriarch over Amid, which had been Sulaqa's residence but which his successors abandoned on having to move eastward into Safavid Iran, had been accepted by the Turkish authorities.)

All the (non-hereditary) successors in Amid of Joseph I, who in 1696 resigned for health reasons and lived on in Rome until 1707, took the name Joseph: Joseph II (1696–1713), Joseph III (1713–1757), Joseph IV (1757–1781). For that reason they are known as the "Josephite line". Joseph IV presented his resignation in 1780 and it was accepted in 1781, after which he handed over the administration of the patriarchate to his nephew, not yet a bishop, and retired to Rome, where he lived until 1791.[64]

Appointment of the nephew as patriarch would look like acceptance of the principle of hereditary succession. Besides, the Alqosh "Eliya line" was drawing closer to Rome, and the pro-Catholic faction within its followers was becoming predominant. For various reasons, including the ecclesiastical as well as political turbulence in Europe after the French Revolution, Rome was long unable to choose between two rival claimants to headship of the Chaldean Catholics.

The 1672 adoption by the "Shimun line" of patriarchs of Nestorian doctrine had been followed in some areas by widespread adoption of the opposing Christology upheld in Rome. This occurred not only in the Amid-Mardin area for which by Turkish decree Joseph I was patriarch, but also in the city of Mosul, where by 1700 nearly all the East Syrians were Catholics.[65] The Rabban Hormizd Monastery, which was the seat of the "Eliya line" of patriarchs is 2 km from the village of Alqosh and about 45 km north of the city of Mosul

In view of this situation, Patriarch Eliya XII wrote to the Pope in 1735, 1749 and 1756, asking for union. Then, in 1771, both he and his designated successor Ishoyabb made a profession of faith that Rome accepted, thus establishing communion in principle. When Eliya XII died in 1778, the metropolitans recognized as his successor Ishoyabb, who accordingly took the Eliya name (Eliya XIII). To win support, Eliya made profession of the Catholic faith, but almost immediately renounced it and declared his support of the traditionalist (Nestorian) view.

Yohannan Hormizd, a member of the "Eliya line" family, opposed Eliya XIII (1778–1804), the last of that line to be elected in the normal way as patriarch. In 1780 Yohannan was irregularly elected patriarch, as Sulaqa had been in 1552. He won over to communion with Rome most followers of the "Eliyya line". The Holy See did not recognize him as patriarch, but in 1791 appointed him archbishop of Amid and administrator of the Catholic patriarchate. The violent protests of Joseph IV's nephew, who was then in Rome, and suspicions raised by others about the sincerity of Yohannan's conversion prevented this being put into effect. In 1793 it was agreed that Yohannan should withdraw from Amid to Mosul, the metropolitan see that he already held, but that the post of patriarch would not be conferred on his rival, Joseph IV's nephew. In 1802 the latter was appointed metropolitan of Amid and administrator of the patriarchate, but not patriarch. Nonetheless, he became commonly known as Joseph V. He died in 1828. Yohannan's rival for the Alqosh title of patriarch had died in 1804, with his followers so reduced in number that they did not elect any successor for him, thus bringing the Alqosh or Eliya line to an end.[65]

Finally then, in 1830, a century and a half after the Holy See had conferred headship of the Chaldeans on Joseph I of Amid, it granted recognition as Patriarch to Yohannan, whose (non-hereditary) patriarchal succession has since then lasted unbroken in the Chaldean Catholic Church.

Later history of the Chaldean Church

In 1838, the Kurds of Soran attacked the Rabban Hormizd Monastery and Alqosh, apparently thinking the villagers were Yazidis responsible for the murder of a Kurdish chieftain, and killed over 300 Chaldeans, including Gabriel Dambo, the refounder of the monastery, and other monks.[66]

In 1846, the Ottoman Empire, which had previously classified as Nestorians those who called themselves Chaldeans, granted them recognition as a distinct millet.[67][68]

The most famous patriarch of the Chaldean Church in the 19th century was Joseph VI Audo who is remembered also for his clashes with Pope Pius IX mainly about his attempts to extend the Chaldean jurisdiction over the Malabar Catholics. This was a period of expansion for the Chaldean Catholic Church.

The activity of the Turkish army and their Kurdish and Arab allies, partly in response to armed support for Russia in the territory of the Qochanis patriarchate, brought ruin also to the Chaldean dioceses of Amid, Siirt and Gazarta and the metropolitans Addai Scher of Siirt and Philip Abraham of Gazarta were killed in 1915).[69]

.jpg)

In the 21st century, Father Ragheed Aziz Ganni, the pastor of the Chaldean Church of the Holy Spirit in Mosul, who graduated from the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum in Rome in 2003 with a licentiate in ecumenical theology, was killed on 3 June 2007 in Mosul alongside the subdeacons Basman Yousef Daud, Wahid Hanna Isho, and Gassan Isam Bidawed, after he celebrated mass.[70][71] Ganni has since been declared a Servant of God.[72]

Chaldean Archbishop Paulos Faraj Rahho and three companions were abducted on 29 February 2008, in Mosul, and murdered a few days later.[73]

21st century: international diaspora

There are many Chaldeans in diaspora in the Western world, primarily in the American states of Michigan, Illinois and California.[74]

In 2006 the Eparchy of Oceania, with the title of 'St Thomas the Apostle of Sydney of the Chaldeans' was set up with jurisdiction including the Chaldean Catholic communities of Australia and New Zealand.[75] Its first Bishop, named by Pope Benedict XVI on 21 October 2006, was Archbishop Djibrail (Jibrail) Kassab, until this date, Archbishop of Bassorah in Iraq.[76]

There has been a large immigration to the United States particularly to West Bloomfield in southeast Michigan.[77] Although the largest population resides in southeast Michigan, there are populations in parts of California and Arizona as well, which all fall under the Eparchy of Saint Thomas the Apostle of Detroit. Canada in recent years has shown growing communities in both eastern provinces, such as Ontario, and in western Canada, such as Saskatchewan.

In 2008, Bawai Soro of the Assyrian Church of the East and 1,000 Assyrian families were received into full communion with the Chaldean Catholic Church.[78]

On Friday, June 10, 2011, Pope Benedict XVI erected a new Chaldean Catholic eparchy in Toronto, Ontario, Canada and named Archbishop Yohannan Zora, who has worked alongside four priests with Catholics in Toronto (the largest community of Chaldeans) for nearly 20 years and who was previously an ad personam Archbishop (he will retain this rank as head of the eparchy) and the Archbishop of the Archdiocese (Archeparchy) of Ahwaz, Iran (since 1974). The new eparchy, or diocese, will be known as the Chaldean Catholic Eparchy of Mar Addai. There are 38,000 Chaldean Catholics in Canada. Archbishop Zora was born in Batnaia, Iraq, on March 15, 1939. He was ordained in 1962 and worked in Iraqi parishes before being transferred to Iran in 1969.[79]

The 2006 Australian census counted a total of 4,498 Chaldean Catholics in that country.[80]

Historic membership censuses

Despite the internal discords of the reigns of Yohannan Hormizd (1830–1838), Nicholas I Zaya (1839–1847) and Joseph VI Audo (1847–1878), the 19th century was a period of considerable growth for the Chaldean church, in which its territorial jurisdiction was extended, its hierarchy strengthened and its membership nearly doubled. In 1850 the Anglican missionary George Percy Badger recorded the population of the Chaldean church as 2,743 Chaldean families, or just under 20,000 persons. Badger's figures cannot be squared with the figure of just over 4,000 Chaldean families recorded by Fulgence de Sainte Marie in 1796 nor with slightly later figures provided by Paulin Martin in 1867. Badger is known to have classified as Nestorian a considerable number of villages in the ʿAqra district which were Chaldean at this period, and he also failed to include several important Chaldean villages in other dioceses. His estimate is almost certainly far too low.[81]

| Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Priests | No. of Families | Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Priests | No. of Families |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosul | 9 | 15 | 20 | 1,160 | Seert | 11 | 12 | 9 | 300 |

| Baghdad | 1 | 1 | 2 | 60 | Gazarta | 7 | 6 | 5 | 179 |

| ʿAmadiya | 16 | 14 | 8 | 466 | Kirkuk | 7 | 8 | 9 | 218 |

| Amid | 2 | 2 | 4 | 150 | Salmas | 1 | 2 | 3 | 150 |

| Mardin | 1 | 1 | 4 | 60 | Total | 55 | 61 | 64 | 2,743 |

Paulin Martin's statistical survey in 1867, after the creation of the dioceses of ʿAqra, Zakho, Basra and Sehna by Joseph Audo, recorded a total church membership of 70,268, more than three times higher than Badger's estimate. Most of the population figures in these statistics have been rounded up to the nearest thousand, and they may also have been exaggerated slightly, but the membership of the Chaldean church at this period was certainly closer to 70,000 than to Badger's 20,000.[82]

| Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Priests | No. of Believers | Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Believers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosul | 9 | 40 | 23,030 | Mardin | 2 | 2 | 1,000 |

| ʿAqra | 19 | 17 | 2,718 | Seert | 35 | 20 | 11,000 |

| ʿAmadiya | 26 | 10 | 6,020 | Salmas | 20 | 10 | 8,000 |

| Basra | – | – | 1,500 | Sehna | 22 | 1 | 1,000 |

| Amid | 2 | 6 | 2,000 | Zakho | 15 | – | 3,000 |

| Gazarta | 20 | 15 | 7,000 | Kirkuk | 10 | 10 | 4,000 |

| Total | 160 | 131 | 70,268 |

A statistical survey of the Chaldean church made in 1896 by J. B. Chabot included, for the first time, details of several patriarchal vicariates established in the second half of the 19th century for the small Chaldean communities in Adana, Aleppo, Beirut, Cairo, Damascus, Edessa, Kermanshah and Teheran; for the mission stations established in the 1890s in several towns and villages in the Qudshanis patriarchate; and for the newly created Chaldean diocese of Urmi. According to Chabot, there were mission stations in the town of Serai d’Mahmideh in Taimar and in the Hakkari villages of Mar Behıshoʿ, Sat, Zarne and 'Salamakka' (Ragula d'Salabakkan).[83]

| Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Priests | No. of Believers | Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Believers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baghdad | 1 | 3 | 3,000 | ʿAmadiya | 16 | 13 | 3,000 |

| Mosul | 31 | 71 | 23,700 | ʿAqra | 12 | 8 | 1,000 |

| Basra | 2 | 3 | 3,000 | Salmas | 12 | 10 | 10,000 |

| Amid | 4 | 7 | 3,000 | Urmi | 18 | 40 | 6,000 |

| Kirkuk | 16 | 22 | 7,000 | Sehna | 2 | 2 | 700 |

| Mardin | 1 | 3 | 850 | Vicariates | 3 | 6 | 2,060 |

| Gazarta | 17 | 14 | 5,200 | Missions | 1 | 14 | 1,780 |

| Seert | 21 | 17 | 5,000 | Zakho | 20 | 15 | 3,500 |

| Total | 177 | 248 | 78,790 |

The last survey of the Chaldean Church before the First World War was made in 1913 by the Chaldean priest Joseph Tfinkdji, after a period of steady growth since 1896. It then consisted of the patriarchal archdiocese of Mosul and Baghdad, four other archdioceses (Amid, Kirkuk, Seert and Urmi), and eight dioceses (ʿAqra, ʿAmadiya, Gazarta, Mardin, Salmas, Sehna, Zakho and the newly created diocese of Van). Five more patriarchal vicariates had been established since 1896 (Ahwaz, Constantinople, Basra, Ashshar and Deir al-Zor), giving a total of twelve vicariates.[84][85]

Tfinkdji's grand total of 101,610 Catholics in 199 villages is slightly exaggerated, as his figures included 2,310 nominal Catholics in twenty-one 'newly converted' or 'semi-Nestorian' villages in the dioceses of Amid, Seert and ʿAqra, but it is clear that the Chaldean church had grown significantly since 1896. With around 100,000 believers in 1913, the membership of the Chaldean church was only slightly smaller than that of the Qudshanis patriarchate (probably 120,000 East Syriac Christians at most, including the population of the nominally Russian Orthodox villages in the Urmi district). Its congregations were concentrated in far fewer villages than those of the Qudshanis patriarchate, and with 296 priests, a ratio of roughly three priests for every thousand believers, it was rather more effectively served by its clergy. Only about a dozen Chaldean villages, mainly in the Seert and ʿAqra districts, did not have their own priests in 1913.

| Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Priests | No. of Believers | Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Priests | No. of Believers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosul | 13 | 22 | 56 | 39,460 | ʿAmadiya | 17 | 10 | 19 | 4,970 |

| Baghdad | 3 | 1 | 11 | 7,260 | Gazarta | 17 | 11 | 17 | 6,400 |

| Vicariates | 13 | 4 | 15 | 3,430 | Mardin | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1,670 |

| Amid | 9 | 5 | 12 | 4,180 | Salmas | 12 | 12 | 24 | 10,460 |

| Kirkuk | 9 | 9 | 19 | 5,840 | Sehna | 1 | 2 | 3 | 900 |

| Seert | 37 | 31 | 21 | 5,380 | Van | 10 | 6 | 32 | 3,850 |

| Urmi | 21 | 13 | 43 | 7,800 | Zakho | 15 | 17 | 13 | 4,880 |

| ʿAqra | 19 | 10 | 16 | 2,390 | Total | 199 | 153 | 296 | 101,610 |

Tfinkdji's statistics also highlight the effect on the Chaldean church of the educational reforms of the patriarch Joseph VI Audo. The Chaldean church on the eve of the First World War was becoming less dependent on the monastery of Rabban Hormizd and the College of the Propaganda for the education of its bishops. Seventeen Chaldean bishops were consecrated between 1879 and 1913, of whom only one (Stephen Yohannan Qaynaya) was entirely educated in the monastery of Rabban Hormizd. Six bishops were educated at the College of the Propaganda (Joseph Gabriel Adamo, Thomas Audo, Jeremy Timothy Maqdasi, Isaac Khudabakhash, Theodore Msayeh and Peter ʿAziz), and the future patriarch Joseph Emmanuel Thomas was trained in the seminary of Ghazir near Beirut. Of the other nine bishops, two (Addaï Scher and Francis David) were trained in the Syro-Chaldean seminary in Mosul, and seven (Philip Yaʿqob Abraham, Yaʿqob Yohannan Sahhar, Eliya Joseph Khayyat, Shlemun Sabbagh, Yaʿqob Awgin Manna, Hormizd Stephen Jibri and Israel Audo) in the patriarchal seminary in Mosul.[86]

|

|

|

|

Organisation

The Chaldean Catholic Church has the following dioceses:

- Patriarchate of Babylon

- Metropolitan Archdioceses of Baghdad, Kirkuk, Tehran, Urmya

- Archdioceses of Ahwaz, Basra, Diyarbakir, Erbil, Mosul

- Eparchies of Aleppe, Alquoch, Amadia, Akra, Beirut, Cairo, St Peter the Apostle of San Diego, St Thomas the Apostle of Detroit, Chaldean Catholic Eparchy of Mar Addai of Toronto, St Thomas the Apostle of Sydney, Salmas, Sulaimaniya, Zaku

- Territories dependent on the Patriarch: Jerusalem, Jordan

The Latin name of the church is Ecclesia Chaldaeorum Catholica.

Hierarchy

The current Patriarch is Louis Sako, elected in January 2013. In October 2007, his predecessor, Emmanuel III Delly became the first Chaldean Catholic patriarch to be elevated to the rank of Cardinal within the Catholic Church.[87]

The present Chaldean episcopate (January 2014) is as follows:

- Louis Raphaël I Sako, Patriarch of Babylon (since February 2013)

- Emil Shimoun Nona, Bishop of St.Thomas the Apostle Chaldean and Assyrian Catholic Diocese of Australia and New Zealand (since 2015)

- Bashar Warda, Archbishop of Erbil (since July 2010)

- Ramzi Garmou, Archbishop of Teheran (since February 1999)

- Thomas Meram, Archbishop of Urmia and Salmas (since 1984)

- Jibrail Kassab, Bishop Emeritus, former Bishop of Sydney (2006–2015)

- Jacques Ishaq, Titular Archbishop of Nisibis and curial Bishop of Babylon (since December 2005)

- Habib Al-Naufali, Archbishop of Basra (since 2014)

- Yousif Mirkis, Archbishop of Kirkuk and Suleimanya (since 2014)

- Mikha Pola Maqdassi, Bishop of Alqosh (since December 2001)

- Shlemon Warduni, curial Bishop of Babylon (since 2001)

- Saad Sirop, auxiliary Bishop of Babylon (since 2014) and Apostolic Visitor of Chaldean Catholic in Europe (since 2017)

- Antony Audo, Bishop of Aleppo (since January 1992)

- Michael Kassarji, Bishop of Lebanon (since 2001)

- Rabban Al-Qas, Bishop of ʿAmadiya (since December 2001)

- Ibrahim Ibrahim, Bishop Emeritus, former Bishop of Saint Thomas the Apostle of Detroit (April 1982–2014)

- Francis Kalabat, Bishop of Saint Thomas the Apostle of Detroit (since June 2014)

- Sarhad Yawsip Jammo, Bishop Emeritus of Saint Peter the Apostle of San Diego (2002–2016)

- Bawai Soro, Bishop of St.Addai Chaldean Eparchy of Canada (since 2017)

- Saad Felix Shabi, Bishop of Zakho (since 2020)

- Robert Jarjis, Auxiliary Bishop of Baghdad (since 2018) and Titular Bishop of Arsamosata (since 2019)

- Emmanuel Shalita, Bishop of St. Peter the Apostle Chaldean Catholic (San Diego, USA, since 2016)

- Basel Yaldo, Curial Bishop of Babylon and Titular Bishop of BethZabda (since 2015)

Several sees are vacant: Archeparchy of Diyarbakir, Archeparchy of Ahwaz, Eparchy of 'Aqra, Eparchy of Cairo.

Liturgy

The Chaldean Catholic Church uses the East Syriac Rite.

A slight reform of the liturgy was effective since 6 January 2007, and it aimed to unify the many different uses of each parish, to remove centuries-old additions that merely imitated the Roman Rite, and for pastoral reasons. The main elements of variations are: the Anaphora said aloud by the priest, the return to the ancient architecture of the churches, the restoration of the ancient use where the bread and wine are readied before a service begins, and the removal from the Creed of the Filioque clause.[88]

Ecumenical relations

The Church's relations with its fellow Assyrians in the Assyrian Church of the East have improved in recent years. In 1994 Pope John Paul II and Patriarch Dinkha IV of the Assyrian Church of the East signed a Common Christological Declaration.[89] On the 20 July 2001, the Holy See issued a document, in agreement with the Assyrian Church of the East, named Guidelines for admission to the Eucharist between the Chaldean Church and the Assyrian Church of the East, which confirmed also the validity of the Anaphora of Addai and Mari.[90]

In 2015, while the patriarchate of the Assyrian Church of the East was vacant following the death of Dinkha IV, the Chaldean Patriarch Louis Raphaël I Sako proposed unifying the three modern patriarchates into a re-established Church of the East with a single Patriarch in full communion with the Pope.[91][92] The Assyrian Church of the East ignored his proposal and proceeded with its election of a new Patriarch.

See also

- List of Chaldean Catholic Patriarchs of Babylon

- Eastern Catholicism

- Liturgies: East Syriac Rite, Holy Qurbana of Addai and Mari

- Film about Chaldean Christians: The Last Assyrians

- Assyrian People

- List of Assyrians

- Names of Syriac Christians

- Syro-Malabar Catholic Church

References

- Introduction To Bibliology: What Every Christian Should Know About the Origins, Composition, Inspiration, Interpretation, Canonicity, and Transmission of the Bible

- Synod of the Chaldean Church | GCatholic.org

- "The Chaldean Catholic Church". CNEWA. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- Eastern Catholic Churches Worldwide 2018

- Statistics on Christians in the Middle East

- Brief Summary on Iraqi Christians

- Iraq 2018 International Religious Freedom Report, p. 3

- European Asylum Support Office: Country Guidance - Iraq (June 2019), p. 70

- Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (8 December 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2.

- Eckart Frahm (24 March 2017). A Companion to Assyria. Wiley. p. 1132. ISBN 978-1-118-32523-0.

- Joseph, John (July 3, 2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: A History of Their Encounter with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers. BRILL. ISBN 9004116419 – via Google Books.

- "Fred Aprim, "Assyria and Assyrians Since the 2003 US Occupation of Iraq"" (PDF). Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- Edmon Louis Gallagher (23 March 2012). Hebrew Scripture in Patristic Biblical Theory: Canon, Language, Text. BRILL. pp. 123, 124, 126, 127, 139. ISBN 978-90-04-22802-3.

- Julius Fürst (1867). A Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament: With an Introduction Giving a Short History of Hebrew Lexicography. Tauchnitz.

- Wilhelm Gesenius; Samuel Prideaux Tregelles (1859). Gesenius's Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament Scriptures. Bagster.

- Benjamin Davies (1876). A Compendious and Complete Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament, Chiefly Founded on the Works of Gesenius and Fürst ... A. Cohn.

- Coakley, J. F. (2011). Brock, Sebastian P.; Butts, Aaron M.; Kiraz, George A.; van Rompay, Lucas (eds.). Chaldeans. Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-59333-714-8.

- "Council of Basel-Ferrara-Florence, 1431-49 A.D.

- Braun-Winkler, p. 112

- Michael Angold; Frances Margaret Young; K. Scott Bowie (17 August 2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 5, Eastern Christianity. Cambridge University Press. p. 527. ISBN 978-0-521-81113-2.

- Wilhelm Braun, Dietmar W. Winkler, The Church of the East: A Concise History (RoutledgeCurzon 2003), p. 83

- Ainsworth, William (1841). "An Account of a Visit to the Chaldeans, Inhabiting Central Kurdistán; and of an Ascent of the Peak of Rowándiz (Ṭúr Sheïkhíwá) in Summer in 1840". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 11. e.g. p. 36. doi:10.2307/1797632. JSTOR 1797632.

- William F. Ainsworth, Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Chaldea and Armenia (London 1842), vol. II, p. 272, cited in John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East (BRILL 2000), pp. 2 and 4

- Layard, Austen Henry (July 3, 1850). Nineveh and its remains: an enquiry into the manners and arts of the ancient assyrians. Murray. p. 260 – via Internet Archive.

Chaldaeans Nestorians.

- Simon (oratorien), Richard (July 3, 1684). "Histoire critique de la creance et des coûtumes des nations du Levant". Chez Frederic Arnaud – via Google Books.

- Rassam, Hormuzd (1897). Asshur and the land of Nimrod. Curts & Jennings. p. – via Internet Archive.

all the Chaldaeans, whether Nestorians or Papal.

- Ely Banister Soane, To Mesopotamia and Kurdistan in disguise : with historical notices of the Kurdish tribes and the Chaldeans of Kurdistan (Small, Maynard and Company 1914)

- George Percy Badger (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals: With the Narrative of a Mission to Mesopotamia and Coordistan in 1842-1844, and of a Late Visit to Those Countries in 1850: Also, Researches Into the Present Condition of the Syrian Jacobites, Papal Syrians, and Chaldeans, and an Inquiry Into the Religious Tenets of the Yezeedees. Joseph Masters.

- Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. JAAS. 18 (2): 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17.

- Mar Raphael J Bidawid. The Assyrian Star. September–October, 1974:5.

- "Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East". Oikoumene.org. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

St Peter, the chief of the apostles added his blessing to the Church of the East at the time of his visit to the see at Babylon, in the earliest days of the church: '... The chosen church which is at Babylon, and Mark, my son, salute you' (I Peter 5:13).

- David M. Gwynn (20 November 2014). Christianity in the Later Roman Empire: A Sourcebook. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4411-3735-7.

- Hill 1988, p. 105.

- Cross, F.L. & Livingstone E.A. (eds), Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 351

- Outerbridge 1952.

- Georgetown University, Mesopotamian Scholasticism: A History of the Christian Theological School in the Syrian Orient: Introduction to Junillus's Instituta Regularia

- Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (8 December 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2.

- Hill 1988, p. 108-109.

- K. C. Zachariah (1 November 2001). "The Syrian Christians of Kerala: A Narsai (Nestorian patriarch)Demographic and Socioeconomic Transition in the Twentieth Century" (PDF). www.cds.edu.

- David Wilmshurst (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913. Peeters Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 978-90-429-0876-5.

- Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (8 December 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2.

- Anthony O'Mahony; Emma Loosley (16 December 2009). Eastern Christianity in the Modern Middle East. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-135-19371-3.

- Patriarcha de Mozal in Syria orientali (Anton Baumstark (editor), Oriens Christianus, IV:1, Rome and Leipzig 2004, p. 277)

- Chaldaeorum ecclesiae Musal Patriarcha (Giuseppe Simone Assemani (editor), Bibliotheca Orientalis Clementino-Vaticana (Rome 1725), vol. 3, part 1, p. 661)

- "L'Église nestorienne" in Dictionnaire de théologie catholique (Librairie Letourzey et Ané (1931), vol. XI, col. 228

- Christoph Baumer (5 September 2016). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-83860-934-4.

- Charles A. Frazee (22 June 2006). Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-521-02700-7.

- Dietmar W. Winkler; Daniel King (editor) (12 December 2018). "7. The Syriac Church Denomination: An overview". The Syriac World. Taylor & Francis. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-317-48211-6.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Mar Aprem Mooken, The History of the Assyrian Church of the East (St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute, 2000), p. 33

- Pietro Strozzi (1617). De dogmatibus chaldaeorum disputatio ad Patrem ... Adam Camerae Patriarchalis Babylonis ... ex typographia Bartholomaei Zannetti.

- A Chronicle of the Carmelites in Persia (Eyre & Spottiswoode 1939), vol. I, pp. 382–383

- In his contribution "Myth vs. Reality" to JAA Studies, Vol. XIV, No. 1, 2000 p. 80, George V. Yana (Bebla) presented as a "correction" of Strozzi's statement a quotation from an unrelated source (cf. p. xxiv) that Sulaqa was called "Patriarch of the Chaldeans".

- Hannibal Travis (20 July 2017). The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. Taylor & Francis. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-351-98025-8.

- Johnson, Ronald (1994). "Assyrians" (PDF). In Levinson, David (ed.). Encyclopedia of World Cultures. 9. G.K. Hall & Company. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0-8161-1815-9. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Assyrian International News Agency Peter BetBasoo, "Brief History of Assyrians"

- Marcantonius Amulilus (1562). R.d. patriarchae Orientalium Assyriorum de Sacro oecumenico Tridentini [!] concilio approbatio, & professio, et literae illustrissimi domini Marciantonij cardinalis Amulij ad legatos Sacri concilij Tridentini.MDLXII.

- Christoph Baumer (5 September 2016). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-83860-933-7.

- K. Christian Girling, "The Chaldean Catholic Church: A study in modern history, ecclesiology and church-state relations (2003–2013)" (University of London, 2015, p. 35

- Frazee 2006, p. 57.

- Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (8 December 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-134-43019-2.

- Eckart Frahm (24 March 2017). A Companion to Assyria. Wiley. p. 1132. ISBN 978-1-118-32523-0.

- Joseph, John (July 3, 2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: A History of Their Encounter with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers. BRILL. ISBN 9004116419 – via Google Books.

- "Fred Aprim, "Assyria and Assyrians Since the 2003 US Occupation of Iraq"" (PDF). Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- Annuaire Pontifical Catholique de 1914, pp. 459−460

- David Wilmshurst (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913. Peeters Publishers. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-90-429-0876-5.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 32, 253.

- George Percy Badger (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals, with the Narrative of a Mission to Mesopotamia and Coordistan in 1842-1844, and of a Late Visit to Those Countries in 1850: Also, Researches Into the Present Condition of the Syrian Jacobites, Papal Syrians, and Chaldeans, and an Inquiry Into the Religious Tenets of the Yezeedees. Joseph Masters. p. 169.

- O’Mahony 2006, p. 528.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 37.

- AsiaNews.it. "A Chaldean priest and three deacons killed in Mosul". www.asianews.it. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "The Chaldean Church mourns Fr. Ragheed Ganni and his martyrs". AsiaNews. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Servant of God, Fr Ragheed Ganni". Pontifical Irish College, Rome. 27 May 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Kidnappers take Iraqi Archbishop, Kill his three companions". Catholic News Service. Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on 2008-03-11. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- "Chaldean Americans at a-glance". Chaldean American Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Eparchy of Saint Thomas t Apostle of Sydney (Chaldean)". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "Archbishop Djibrail Kassab". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "Eparchy of Saint Thomas the Apostle of Detroit (Chaldean)". Catholic-Hierarchy.org. David M. Cheney. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- "Assyrian Bishop Mar Bawai Soto explains his journey into communion with the Catholic Church". kaldaya.net. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- "CNS NEWS BRIEFS Jun-10-2011". Catholicnews.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- 2006 Religious Affiliation (Full Classification). "» 2006 Religious Affiliation (Full Classification) The Census Campaign Australia". Census-campaign.org.au. Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- Badger, Nestorians, i. 174–5

- Martin, La Chaldée, 205–12

- Chabot 1896, p. 433-453.

- Tfinkdji 1914, p. 476–520.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 362.

- Wilmshurst 2000, p. 360-363.

- AP

- "Q & A on the Reformed Chaldean Mass". Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- "Common Christological Declaration between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East". Vatican. Archived from the original on 2009-01-04. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- "Guidelines issued by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity". Vatican. Archived from the original on 2015-11-03. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- Valente, Gianni (25 June 2015). "Chaldean Patriarch gambles on re-establishing "Church of the East"". Vatican Insider.

- "Chaldean Patriarch gambles on re-establishing 'Church of the East'” La Stampa 25 June 2015. Accessed 11 May 2017.

Sources

- Assemani, Giuseppe Simone (1719). Bibliotheca orientalis clementino-vaticana. 1. Roma.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (1775). De catholicis seu patriarchis Chaldaeorum et Nestorianorum commentarius historico-chronologicus. Roma.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (2004). History of the Chaldean and Nestorian patriarchs. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Becchetti, Filippo Angelico (1796). Istoria degli ultimi quattro secoli della Chiesa. 10. Roma.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Badger, George Percy (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals. 1. London: Joseph Masters.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Badger, George Percy (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals. 2. London: Joseph Masters.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baumer, Christoph (2006). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. London-New York: Tauris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beltrami, Giuseppe (1933). La Chiesa Caldea nel secolo dell’Unione. Roma: Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chabot, Jean-Baptiste (1896). "Éttat religieux des diocèses formant le patriarcat chaldéen de Babylone". Revue de l'Orient chrétien. 1: 433–453.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chaumont, Marie-Louise (1988). La Christianisation de l'Empire Iranien: Des origines aux grandes persécutions du ive siècle. Louvain: Peeters.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1967). "Les étapes de la prise de conscience de son identité patriarcale par l'Église syrienne orientale". L'Orient Syrien. 12: 3–22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970). Jalons pour une histoire de l'Église en Iraq. Louvain: Secretariat du CSCO.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1979) [1963]. Communautés syriaques en Iran et Irak des origines à 1552. London: Variorum Reprints.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1993). Pour un Oriens Christianus Novus: Répertoire des diocèses syriaques orientaux et occidentaux. Beirut: Orient-Institut.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frazee, Charles A. (2006) [1983]. Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Giamil, Samuel (1902). Genuinae relationes inter Sedem Apostolicam et Assyriorum orientalium seu Chaldaeorum ecclesiam. Roma: Ermanno Loescher.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gulik, Wilhelm van (1904). "Die Konsistorialakten über die Begründung des uniert-chaldäischen Patriarchates von Mosul unter Papst Julius III" (PDF). Oriens Christianus. 4: 261–277.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Habbi, Joseph (1966). "Signification de l'union chaldéenne de Mar Sulaqa avec Rome en 1553". L'Orient Syrien. 11: 99–132, 199–230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Habbi, Joseph (1971a). "L'unification de la hiérarchie chaldéenne dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 2 (1): 121–143.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Habbi, Joseph (1971b). "L'unification de la hiérarchie chaldéenne dans la première moitié du XIXe siècle (Suite)" (PDF). Parole de l'Orient. 2 (2): 305–327.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hage, Wolfgang (2007). Das orientalische Christentum. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, Henry, ed. (1988). Light from the East: A Symposium on the Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches. Toronto: Anglican Book Centre.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jakob, Joachim (2014). Ostsyrische Christen und Kurden im Osmanischen Reich des 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhunderts. Münster: LIT Verlag.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Labourt, Jérôme (1908). "Note sur les schismes de l'Église nestorienne, du XVIe au XIXe siècle". Journal asiatique. 11: 227–235.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lampart, Albert (1966). Ein Märtyrer der Union mit Rom: Joseph I. 1681–1696, Patriarch der Chaldäer. Einsiedeln: Benziger Verlag.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lemmens, Leonhard (1926). "Relationes nationem Chaldaeorum inter et Custodiam Terrae Sanctae (1551-1629)". Archivum Franciscanum Historicum. 19: 17–28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marthaler, Berard L., ed. (2003). "Chaldean Catholic Church (Eastern Catholic)". The New Catholic Encyclopedia. 3. Thompson-Gale. pp. 366–369.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murre van den Berg, Heleen H. L. (1999). "The Patriarchs of the Church of the East from the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 2 (2): 235–264. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2017-08-19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nichols, Aidan (2010) [1992]. Rome and the Eastern Churches: A Study in Schism (2nd revised ed.). San Francisco: Ignatius Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O’Mahony, Anthony (2006). "Syriac Christianity in the modern Middle East". In Angold, Michael (ed.). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Eastern Christianity. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 511–536.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Outerbridge, Leonard M. (1952). The lost churches of China. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberson, Ronald (1999) [1986]. The Eastern Christian Churches: A Brief Survey (6th ed.). Roma: Orientalia Christiana.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tfinkdji, Joseph (1914). "L' église chaldéenne catholique autrefois et aujourd'hui". Annuaire pontifical catholique. 17: 449–525.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tisserant, Eugène (1931). "Église nestorienne". Dictionnaire de théologie catholique. 11. pp. 157–323.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vine, Aubrey R. (1937). The Nestorian Churches. London: Independent Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1930). "Les inscriptions de Rabban Hormizd et de N.-D. des Semences près d'Alqoš (Iraq)". Le Muséon. 43: 263–316.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1931). "Mar Iohannan Soulaqa, premier Patriarche des Chaldéens, martyr de l'union avec Rome (†1555)". Angelicum. 8: 187–234.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wigram, William Ainger (1929). The Assyrians and Their Neighbours. London: G. Bell & Sons.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Louvain: Peeters Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilmshurst, David (2011). The martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing Limited.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chaldean Catholic Church. |

- Chaldean Catholic Church Mass Times

- Article on the Chaldean Catholic Church by Ronald Roberson on the CNEWA web site

- Chaldean Catholic Diocese of Saint Peter

- East Syriac Rite (Catholic Encyclopedia)

- Daughters of the Immaculate Conception, a congregation located in Michigan

- Guidelines for Chaldean Catholics receiving the Eucharist in Assyrian Churches

- History of the Chaldean Church

- Qambel Maran- Syriac chants from South India- a review and liturgical music tradition of Syriac Christians revisited

- Homepage of Fr. Damian Hungs (in German)