Strasbourg Cathedral

Strasbourg Cathedral or the Cathedral of Our Lady of Strasbourg (French: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg, or Cathédrale de Strasbourg, German: Liebfrauenmünster zu Straßburg or Straßburger Münster), also known as Strasbourg Minster, is a Catholic cathedral in Strasbourg, Alsace, France. Although considerable parts of it are still in Romanesque architecture, it is widely considered[3][4][5][6] to be among the finest examples of Rayonnant Gothic architecture. Erwin von Steinbach is credited for major contributions from 1277 to his death in 1318.

| Strasbourg Cathedral | |

|---|---|

Strasbourg Cathedral's west façade, viewed from Rue Mercière | |

| |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1647 to 1874[I] | |

| Preceded by | St. Mary's Church, Stralsund |

| Surpassed by | St. Nicholas' Church, Hamburg |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Romanesque Gothic |

| Location | Strasbourg, France |

| Coordinates | 48°34′54″N 7°45′03″E |

| Construction started | 1015 |

| Completed | 1439 |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 142 m (466 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | n/a |

| References | |

| [1] | |

| Strasbourg Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of Our Lady of Strasbourg | |

| Strasbourg Minster | |

Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg | |

The spire of Strasbourg Cathedral seen from the south-east | |

| |

| Location | Strasbourg |

| Country | France |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Previous denomination | Protestantism |

| Website | http://www.cathedrale-strasbourg.fr |

| History | |

| Former name(s) | Liebfrauenmünster zu Straßburg |

| Founder(s) | Werner I |

| Dedication | Mary, mother of Jesus |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | cathedral |

| Heritage designation | Monument historique |

| Designated | 1862 |

| Architect(s) | Erwin von Steinbach Johannes von Steinbach Master Gerlach Michael von Freiburg Claus von Lohre Ulrich Ensingen Johannes Hültz Jakob von Landshut Gustave Klotz |

| Architectural type | basilica |

| Style | Romanesque Rayonnant |

| Years built | 424 |

| Groundbreaking | 1015 |

| Completed | 1439 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 112 m (367 ft) |

| Number of domes | 1 |

| Dome height (outer) | 58 m (190 ft) |

| Number of spires | 1 |

| Spire height | 142 m (466 ft) |

| Materials | sandstone |

| Bells | 20[2] |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Archdiocese of Strasbourg |

| Clergy | |

| Archbishop | Luc Ravel |

At 142 metres (466 feet), it was the world's tallest building from 1647 to 1874 (227 years), when it was surpassed by St. Nikolai's Church, Hamburg. Today it is the sixth-tallest church in the world and the highest extant structure built entirely in the Middle Ages.

Described by Victor Hugo as a "gigantic and delicate marvel",[7] and by Goethe as a "sublimely towering, wide-spreading tree of God",[3] the cathedral is visible far across the plains of Alsace and can be seen from as far off as the Vosges Mountains or the Black Forest on the other side of the Rhine. Sandstone from the Vosges Mountains used in construction gives the cathedral its characteristic pink hue.

The construction, and later maintenance, of the cathedral is supervised by the "Foundation of Our Lady" (Fondation de l'Œuvre Notre-Dame) since 1224.[8]

History

Previous buildings on the site

Archaeological excavations below and around the cathedral have been conducted in 1896–1897,[9] 1907,[10] 1923–1924,[11] 1947–1948,[12] between 1966 and 1972,[13] and finally between 2012 and 2014.[14]

The site of the current cathedral was used for several successive religious buildings, starting from the Argentoratum period, when a Roman sanctuary occupied the site up to the building that is there today.

It is known that a cathedral was erected by the bishop Saint Arbogast of the Strasbourg diocese at the end of the seventh century, on the base of a temple dedicated to the Virgin Mary, but nothing remains of it today. Strasbourg's previous cathedral, of which remains dating back to the late 4th century or early 5th century were unearthed in 1948 and 1956, was situated at the site of the current Église Saint-Étienne.

In the eighth century, the first cathedral was replaced by a more important building that would be completed under the reign of Charlemagne. Bishop Remigius von Straßburg (also known as Rémi) wished to be buried in the crypt, according to his will dated 778. It was certainly in this building that the Oaths of Strasbourg were pronounced in 842. Excavations revealed that this Carolingian cathedral had three naves and three apses. A poem described this cathedral as decorated with gold and precious stones by the bishop Ratho (also Ratald or Rathold). The basilica caught fire on multiple occasions, in 873, 1002, and 1007.

In 1015, bishop Werner von Habsburg laid the first stone of a new cathedral on the ruins of the Carolingian basilica. He then constructed a cathedral in the Romanesque style of architecture. That cathedral burned to the ground in 1176 because at that time the naves were covered with a wooden framework.

After that disaster, bishop Heinrich von Hasenburg decided to construct a new cathedral, to be more beautiful than that of Basel, which was just being finished. Construction of the new cathedral began on the foundations of the preceding structure, and did not end until centuries later. Werner's cathedral's crypt, which had not burned, was kept and expanded westwards.

Construction of the cathedral (1176–1439)

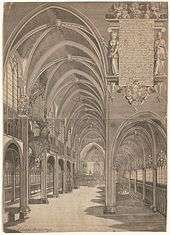

The construction began with the choir and the north transept in a Romanesque style, reminiscent of and actually inspired by the Imperial Cathedrals in its monumentality and height. But in 1225, a team coming from Chartres revolutionized the construction by suggesting a Gothic architecture style. The parts of the nave that had already been begun in Romanesque style were torn down and in order to find money to finish the nave, the Chapter resorted to Indulgences in 1253. The money was kept by the Œuvre Notre-Dame, which also hired architects and stone workers. The influence of the Chartres masters was also felt in the sculptures and statues: the "Pillar of Angels" (Pilier des anges), a representation of the Last Judgment on a pillar in the southern transept, facing the Astronomical clock, owes to their expressive style.

Like the city of Strasbourg, the cathedral connects German and French cultural influences, while the eastern structures, e.g. the choir and south portal, still have very Romanesque features, with more emphasis placed on walls than on windows.

Above all, the famous west front, decorated with thousands of figures, is a masterpiece of the Gothic era. The tower is one of the first to rely substantially on craftsmanship, with the final appearance being one with a high degree of linearity captured in stone. While previous façades were certainly drawn prior to construction, Strasbourg has one of the earliest façades whose construction is inconceivable without prior drawing. Strasbourg and Cologne Cathedral together represent some of the earliest uses of architectural drawing. The work of Professor Robert O. Bork of the University of Iowa suggests that the design of the Strasbourg façade, while seeming almost random in its complexity, can be constructed using a series of rotated octagons. The west front of the cathedral was the work of chief architect (magister operis) Erwin von Steinbach. Erwin von Steinbach's son Johannes von Steinbach served as magister operis from (at least) 1332 until his death in 1341.[15] From 1341 until 1372, the post of chief architect was held by a Master Gerlach about whom little is known (not to be confused with Erwin's other son, architect Gerlach von Steinbach),[16] and in the years 1383–1387, a Michael von Freiburg (also known as Michael von Gmünd, or Michael Parler, from the Parler family) is recorded as magister operis;[17] he was succeeded by Claus von Lohre (1388−1399).[18]

The octagonal north tower as it can be seen is the combined work of architects Ulrich Ensingen (shaft) and Johannes Hültz of Cologne (top). Ensingen worked on the cathedral from 1399 to 1419, taking over from Claus von Lohre, and Hültz from 1419 to 1439, completing the building at last.[19]

The north tower was the world's tallest building from 1647 (when the spire of St. Mary's church, Stralsund burnt down) until 1874 (when the tower of St. Nikolai's Church in Hamburg was completed). The planned south tower was never built and as a result, with its characteristic asymmetrical form, the cathedral is now the premier landmark of Alsace. One can see 30 kilometers from the observation level, which provides a view of the Rhine banks from the Vosges all the way to the Black Forest.

In 1505, architect Jakob von Landshut and sculptor Hans von Aachen finished rebuilding the Saint-Lawrence portal (Portail Saint-Laurent) outside the northern transept in a markedly post-Gothic, early-Renaissance style. As with the other portals of the cathedral, most of the statues now to be seen in situ are copies, the originals having been moved to the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

Later history

In the late Middle Ages, the city of Strasbourg had managed to liberate itself from the domination of the bishop and to rise to the status of Free Imperial City. The outgoing 15th century was marked by the sermons of Johann Geiler von Kaisersberg and by the emerging Protestant Reformation, represented in Strasbourg by figures such as John Calvin, Martin Bucer and Jacob Sturm von Sturmeck. In 1524, the city council assigned the cathedral to the Protestant faith, while the building suffered some damage from iconoclastic assaults. In 1539, the world's first documented Christmas tree was set up inside the Münster. After the annexation of the city by Louis XIV of France, on 30 September 1681, and a mass celebrated in the cathedral on 23 October 1681 in presence of the king and prince-bishop Franz Egon of Fürstenberg,[20] the cathedral was returned to the Catholics and its inside redesigned according to the Catholic liturgy of the Counter-Reformation. In 1682, the choir screen (built in 1252) was broken out to expand the choir towards the nave. Remains of the choir screen are displayed in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame and in The Cloisters.[21] The main or high altar, a major work of early Renaissance sculpture, was also demolished that year.[22] Fragments can be seen in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

A round, Baroque sacristy of modest proportions was added north-east of the northern transept in 1744 by the city's chief architect Joseph Massol according to plans by Robert de Cotte and between 1772 and 1778 architect Jean-Laurent Goetz surrounded the cathedral by a gallery in early Gothic Revival style in order to reorganise the merchants shops that used to settle around the building (and would do so until 1843).[19]

In April 1794, the Enragés who ruled the city started planning to tear the spire down, on the grounds that it hurt the principle of equality. The tower was saved, however, when in May of the same year citizens of Strasbourg crowned it with a giant tin Phrygian cap of the kind the Enragés themselves wore.[23] This artifact was later kept in the historical collections of the city until they were all destroyed during the Siege of Strasbourg in a massive fire in August 1870.[24] During the same siege, the cathedral was hit by Prussian artillery and the metal cross on the spire was bent.[23] The crossing dome's roof was pierced and it was subsequently reconstructed in a grander, Romanesque revival style by the Notre-Dame workshop's longtime chief architect, Gustave Klotz.[25]

During World War II, the cathedral was seen as a symbol for both warring parties. Adolf Hitler, who visited it on 28 June 1940, intended to transform the church into a "national sanctuary of the German people",[26] or into a monument to the Unknown German Soldier.[27] On 1 March 1941, General Leclerc made the "Oath of Kufra" (serment de Koufra), stating he would "rest the weapons only when our beautiful colours fly again on Strasbourg's cathedral".[28] During that same war, the stained glass was removed in 74 cases[29] and stored in a salt mine near Heilbronn, Germany. After the war, it was returned to the cathedral by the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives section of the United States military.[30]

The cathedral was hit by British and American bombs during air raids on Strasbourg's center on 11 August 1944, which also heavily damaged the Palais Rohan and the Sainte-Madeleine Church. In 1956, the Council of Europe donated the famous choir window by Max Ingrand, the "Strasbourg Madonna" (see also Flag of Europe Biblical interpretation). Repairs to war damage were completed only in the early 1990s.

In October 1988, when the city celebrated its 2,000th anniversary (as the first official mention of Argentoratum dates from 12 BC), pope John Paul II visited and celebrated mass in the cathedral.[31] The bishopric of Strasbourg had been elevated to the rank of archbishopric a few months before, in June 1988.[32]

In 2000, an Al-Qaeda plot to bomb the adjacent Christmas market was prevented by French and German police.[33]

Personalities

- Johann Geiler von Kaisersberg, preacher (1478–1510)

- Matthäus Zell, preacher (1518–1523)

- Caspar Hedio, preacher (1523–1550)

- Johann Conrad Dannhauer, priest (1633–1666)

- Philipp Jakob Spener, preacher (1663–1666)

- Franz Xaver Richter, Kapellmeister (1769–1789)

- Ignaz Pleyel, Kapellmeister (1783–1795)

Burials

- Conrad de Lichtenberg

Dimensions

The known dimensions of the building are as follows:[34]

- Total length: 112 m (367 ft)

- Total length inside: 103 m (338 ft)[35]

- Height of spire: 142 m (466 ft)

- Height of observation deck: 66 m (217 ft)

- Height of crossing dome: 58 m (190 ft)

- Exterior height of central nave: 40 m (130 ft)

- Inside height of central nave: 32 m (105 ft)

- Inside width of central nave: 16 m (52 ft)[35]

- Inside height of lateral naves: 19 m (62 ft)

- Inside height of narthex: 42 m (138 ft)

- Exterior width of west façade: 51.5 m (169 ft)

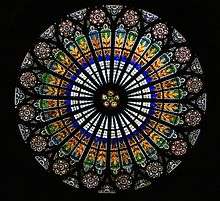

- Diameter of west façade rose window: 13.6 m (45 ft)

- Main construction area: 6,044 m2 (65,060 sq ft)

- Copper-covered roof area: 4,900 m2 (53,000 sq ft)

- Tile-covered roof area: 600 m2 (6,500 sq ft)

- Slate-covered roof area: 47 m2 (510 sq ft)

Furnishing

Protestant and Revolutionary iconoclasm, the war periods of 1681, 1870 and 1940–1944 as well as changes in taste and liturgy have taken a toll on some of Strasbourg Cathedral's most outstanding features such as the choir screen of 1252 and the successive high altars (ca. 1500 and 1682), but many treasures remain inside the building; others, or fragments of them, being displayed in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame.

The outstanding elements are:

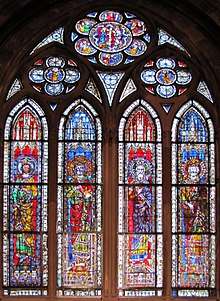

- Stained glass windows, mostly 14th century, some late 12th century (northern transept) and 13th century (see also below, Emperor Windows), some 20th century (southern transept, choir). Stained glass windows from the former Dominican Church, destroyed in 1870, in the Chapelle Saint-Laurent and Chapelle Saint-André.

- Tombstone of Conrad de Lichtenberg in the Chapelle Saint-Jean-Baptiste, ca. 1300. Facing it, monument to a canon by Nikolaus Gerhaert (1464).

- Richly ornate baptismal font by Jost Dotzinger in the northern transept, 1443

- Richly ornate pulpit by Hans Hammer, north-east of the central nave, 1486

- Life-sized group of sculptures "Christ on the Mount of Olives" in the northern transept, facing the baptismal font (previously in the Église Saint-Thomas), 1498; the cross towering above it is from 1825[36]

- Suspended pipe organ on the north side of the central nave (Organ case of 1385, 1491; mechanism and registers by Alfred Kern, 1981)[37]

- Choir pipe organ, north side of the choir, Joseph Merklin, 1878[38]

- Crypt pipe organ, 1998[39]

- Busts of Apostles from the high altar of 1682 along the semi-circular wall closing the choir, wood, 17th century

- Tapestries "Life of Mary", Paris, 17th century, acquired by the cathedral's chapter in the 18th century

- Altars in the chapels (15th–19th centuries); large Baroque altar of 1698 (structure) and 1776 (paintings) in the Chapelle Saint-Laurent

Emperor Windows (Kaiserfenster)

The Northern lateral nave is lit by a unique set of five windows depicting 19 Emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, dating mostly from the 12th and 13th centuries, some subsequently heavily restored. From West to East, and with names as in each Emperor's nimbus, which may have been added in the 14th century:[40]

- First Emperor Window: HENRICUS REX (presumably Henry the Fowler), FRIDERICUS REX (Frederick I), HENRICUS BABINBERGENSIS (Henry II of Bamberg);

- Second Emperor Window: OTTO REX (Otto I), OTTO II REX (Otto II), OTTO III REX (Otto III), CONRADUS II REX (Conrad II), the latter depicted together with an imperial prince who may be Henry III;

- Third Emperor Window: REX PHILIPPUS (Philip of Swabia), HENRICUS REX BABINBERG[ensis] (possibly Henry II), REX HENRICUS CLAUDUS (Henry the lame = also possibly Henry II), FRIDERICUS IMP[er]ATOR SUBMERSUS (Frederick I);

- Fourth Emperor Window: KAROLUS D[ic]C[tu]S MARTEL PATER BIPPINI (Charles Martel), KAROLUS MAGNUS REX (Charlemagne), REX BIPPINUS P[ate]R KAROLI (Pepin the Short), LUDEVICUS REX FILIUS KAROLI (Louis the Pious);

- Fifth Emperor Window: LOTHARIUS ROMANORUM IMPERATOR (Lothair I), LUDEWICUS FILIUS LOTHARII VIII (identification unclear, may be Louis II of Italy), LUDEWICUS FILIUS LOTHARI VI (identification unclear), KAROLUS REX IUNIOR (identified with Charles of Provence).

Astronomical clock

The cathedral's south transept houses an 18-metre astronomical clock, one of the largest in the world. Its first forerunner was the so-called Dreikönigsuhr ("three-king clock") of 1352–1354, located at the opposite wall from where today's clock is. Then starting in 1547 a new clock was built by Christian Herlin, and others, but the construction was interrupted when the cathedral was handed over to the Roman Catholic Church. Construction was resumed in 1571 by Conrad Dasypodius and the Habrecht brothers, and this clock was astronomically much more involved. It also had paintings by the Swiss painter Tobias Stimmer. That clock functioned into the late 18th century and can be seen today in the Strasbourg Museum of Decorative Arts.

The clock existing today originated in 1838–1843 (the clock has 1838–1842, but the celestial globe was only finished on June 24, 1843) and was built by Jean-Baptiste Schwilgué in Dasypodius' clock case, and with roughly the same functions, but equipped with completely new mechanics. Schwilgué made a number of preliminary studies years before, such as a design of the computus mechanism (Easter computation) in 1816, and built a prototype in 1821. This mechanism, whose whereabouts are now unknown, could compute Easter following the complex Gregorian rule.

The astronomical part is unusually accurate; it indicates leap years, equinoxes, and more astronomical data. Thus it was already much more a complex calculating machine than a clock. Often the complicated functioning of the Strasbourg Clock made specialized mathematical knowledge necessary (not just technical knowledge). The clock was able to determine the computus (date of Easter in the Christian calendar) at a time when computers did not yet exist. Easter had been defined at the First Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325 as "the Sunday that follows the fourteenth day of the moon that falls on March 21 or immediately after". (See also Easter controversy, Ecclesiastical new moon, and Paschal Full Moon.)

Today tourists see only the sculpted figurines of this clock, but behind this ensemble there is a mechanism that engages and that represents one of the most beautiful curiosities of the cathedral. The animated characters launch into movement at different hours of the day. One angel sounds the bell while a second turns over an hourglass. Different characters, representing the ages of life (from a child to an old man) parade in front of Death. On the last level are the Apostles, passing in front of Christ. The clock shows much more than the official time; it also indicates solar time, the day of the week (each represented by a god of mythology), the month, the year, the sign of the zodiac, the phase of the moon and the position of several planets. All these automata are put into operation at 12:30 PM.

According to legend, the creator of this clock had his eyes gouged out afterward, to prevent him from reproducing it. Similar legends are told for other clocks, such as the astronomical clock in Prague.

In the same room, there is a statue of a man resting his elbows on a balustrade. According to legend this was a rival architect to the one who had built the pillar of angels, the architectural feat of the era, who contended that one single pillar could never support such a large vault, and he would wait to see the whole thing come crashing down.[41]

A visitor's commentary of this clock was given after his visit in the summer of 1855 by Theodore Nielsen, a Danish kleinsmith journeyman in his memoirs.[42] As follows. "Everybody knows about the cathedral which is called Munsteren. There is a unique clock in the tower. Surely the only one in the entire world. It shows all time changes, Sun and moon eclipses besides the ordinary times of day. On top of the clock is a niche in which stands Death with a bell in one hand and a crossbone in the other. With this bone he hits the bell each hour to count the time. A Christ figure stands in yet another niche. On each side is a door, and when the clock strikes twelve the left hand door opens and the twelve apostles appear, one at a time. Each one bows deeply before Jesus who in turn lifts his right hand in benediction. Each one then disappears through the door to the right. When Judas appears Jesus hides his face in a fold of his cape. Besides all this there is an enormous rooster that crows and flaps his wings at the same time the Death figure hits the bell with the bone. Above and to the right is a life sized figure, a replica of the man who made the clock. He sits and looks down on his handiworks and you have to look twice to realize that it is not a living person sitting there. Parisians wanted a clock just like that for the Cathedral of Notre Dame. So the burghers of Strassburgh blinded the artist in order to make him unable to undertake the commission. He then asked to be taken up into the tower just once more and this was granted. While up there he put the mechanism out of commission, and the clock was stopped for many years. Several able watchmakers volunteered their entire time to try to get the clock to work again. Some of them became deranged of sheer frustration. But at last someone found the key and since then the clock performs perfectly once more."

There are several models of the Strasbourg clock, usually with simplified functions. One is in the Sydney Powerhouse Museum.[43]

From 1858 until 1989, the clock was maintained by the Ungerer company. This company was founded in 1858 by two brothers, Albert and Théodore Ungerer (Tomi Ungerer's great grandfather) who were Schwilgué's assistants and later in charge of the astronomical clock for three generations. Since 1989, the clock has been maintained by Alfred Faullimmel and his son Ludovic. Mr. Faullimmel had been employed by Ungerer between 1955 and 1989.

Legends

One legend says that the building rests on immense piles of oak sinking into the waters of an underground lake. A boat would roam around the lake, without anyone inside, though the noise of the oars could be heard nevertheless. According to the legend, the entry to the underground lake could be found in the cellar of a house just opposite the cathedral. It would have been walled up a few centuries ago.

The legend of the wind blowing around the cathedral is as follows: In olden days, the Devil flew over the ground, riding the wind. Thus he caught a glimpse of his portrait carved onto the cathedral: the Tempter, courting the foolish virgins (Matthew 25:1–13), in the guise of a seductive young man. It is true that his back opens up and toads and snakes come out of it, but none of the naïve girls notices that — nor do many tourists for that matter. Very flattered and curious, the Devil had the idea to enter to see whether there were other sculptures representing him on the inside of the cathedral. Taken captive inside the holy place, he could not come back out. The wind always waits in the square and still howls today from impatience on the places outside the cathedral. The Devil, furious, makes air currents from the bottom of the church to the height of the pillar of angels.

See also

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- List of Gothic Cathedrals in Europe

- Episcopal Palace, Strasbourg

- Kammerzell House

- Parable of the Ten Virgins

- Sabina von Steinbach

- Saint-Thiébaut Church, Thann

- St. George's Church, Sélestat

- St. Peter and St. Paul's Church, Wissembourg

References

- Strasbourg Cathedral at Emporis

- de Chalendar, Hervé. "Le " couronnement musical " de la cathédrale". L'Alsace-Le Pays. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Susan Bernstein: Goethe's Architectonic Bildung and Buildings in Classical Weimar, The Johns Hopkins University Press

- "Strasbourg Cathedral Hangs On", The Christian Science Monitor, 13 October 1991

- "Art: France's 25", Time, 2 April 1945

- The Woman Who Rode Away and Other Stories – D. H. Lawrence, Dieter Mehl – Google Livres. Books.google.com. 1924-02-06. ISBN 9780521294300. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- "Prodige du gigantesque et du délicat (translation)". Trekearth.com.

- "Notre histoire – OND". Fondation de l'Œuvre Notre-Dame. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Schnitzler, Bernadette; Waton, Marie-Dominique. "Chronologie des fouilles archéologiques". DRAC Alsace. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- "Crypte de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg". acpasso.free.fr. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- Schnitzler, Bernadette; Lefort, Nicolas. "17. Johann Knauth, le sauveur de la cathédrale". docpatdrac.hypotheses.org. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- Hatt, Jean-Jacques. "Les récentes fouilles de Strasbourg (1947–1948), leurs résultats pour la chronologie d'Argentorate". persee.fr. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- "Découverte majeure sous la cathédrale : un bassin antique serait la première piscine baptismale de Strasbourg". inrap.fr. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- "Des légionnaires romains aux bâtisseurs de la cathédrale : la fouille de la place du Château à Strasbourg". inrap.fr. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- "Erwin von Steinbach". Deutsche Biographie. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Recht, Roland (1978). Die Parler und der Schöne Stil 1350–1400, vol. 1. Museen des Stadt Köln. p. 282.

- Schock-Werner, Barbara (1978). Die Parler und der Schöne Stil 1350−1400, vol. 3. Cologne: Museen der Stadt Köln. p. 9.

- "5.2.2.5. La flèche". BS Encyclopédie. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- Les grandes dates de l’histoire de la Cathédrale de Strasbourg Archived 2008-11-17 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- La prise de Strasbourg : 1681 (in French)

- Strasbourg Virgin, on The Cloisters database

- Retable du maître-autel(in French)

- Kurtz, Michael J. (2006). America and the return of Nazi contraband. Cambridge University Press. pp. 171–172.

- "Strasbourg Cathedral and the French Revolution (1789–1802)". Inlibroveritas.net. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- Recht, Roland; Foessel, Georges; Klein, Jean-Pierre: Connaître Strasbourg, 1988, p. 48 ISBN 2-7032-0185-0

- "Nazideutschland im Elsass" (in German)

- Fest, Joachim C. (1973). Hitler. Verlagg Ulstein. p. 689. ISBN 0-15-602754-2.

- Le serment de Koufra Archived 2007-09-18 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- Kurtz, Michael J. (2006). America and the return of Nazi contraband. Cambridge University Press. p. 132.

- Kurtz, Michael J. (2006). America and the return of Nazi contraband. Cambridge University Press. p. 164.

- "CÉLÉBRATION DANS LA CATHÉDRALE DE NOTRE-DAME À STRASBOURG HOMÉLIE DU PAPE JEAN-PAUL II Samedi, 8 octobre 1988". vatican.va. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Eglise catholique. Diocèse. Strasbourg". Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- France Convicts Islamic Militants - CBS.com

- "Straßburger Münster, Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg" (in German). "Dombaumeister E.v.". n.d. Archived from the original on 2016-03-09. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- "Straßburger Münster – Münster Unserer Lieben Frau" (in German). deu.archinform.net. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- La Croix de Mission du transept Nord de la cathédrale Archived 2012-04-08 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- The nave organ Archived 2014-11-02 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- The choir organ Archived 2015-05-11 at the Wayback Machine(in French)

- The crypt organ Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- Adolphe Napoléon Didron (1851). Christian Iconography; or, The History of Christian Art in the Middle Ages.

- This section largely translated from L'horloge astronomique and Astronomische Uhr .

- "With Staff in Hand" Memories of my wanderings in foreign lands. Aarhus Jutland Publishing 1903

- "Strasburg clock". Powerhousemuseum.com. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

Further reading

- Doré, Joseph; Jordan, Benoît; Rapp, Francis; et al.: Strasbourg – La grâce d'une cathédrale, 2007, ISBN 2-7165-0716-3

- Bengel, Sabine; Nohlen, Marie-José; Potier, Stéphane: Bâtisseurs de Cathédrales. Strasbourg, mille ans de chantier, 2014, ISBN 2-8099-1251-3

- Baumann, Fabien; Muller, Claude: Notre-Dame de Strasbourg, Du génie humain à l’éclat divin, 2014, ISBN 2-7468-3188-0

- Recht, Roland; Foessel, Georges; Klein, Jean-Pierre: Connaître Strasbourg, 1988, ISBN 2-7032-0185-0, pages 47–55

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg. |

- Cathédrale de Strasbourg

- Œuvre Notre-Dame

- Strasbourg Cathedral

- Exterior of Notre-Dame de Strasbourg and Interior of Notre-Dame de Strasbourg on archi-wiki.org

- Notre Dame Cathedral (original plans and contemporary photographs)

- Historical Sketch of the Cathedral of Strasbourg at Project Gutenberg

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by St. Mary's Church, Stralsund |

World's tallest structure 1647–1874 142 m |

Succeeded by St. Nicholas' Church, Hamburg |