Iranian architecture

Iranian architecture or Persian architecture (Persian: معمارى ایرانی, Memāri e Irāni) is the architecture of Iran and parts of the rest of West Asia, the Caucasus and Central Asia. Its history dates back to at least 5,000 BC with characteristic examples distributed over a vast area from Turkey and Iraq to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and from the Caucasus to Zanzibar. Persian buildings vary from peasant huts to tea houses, and garden pavilions to "some of the most majestic structures the world has ever seen".[2] In addition to historic gates, palaces, and mosques, the rapid growth of cities such as the capital Tehran has brought about a wave of demolition and new construction.

| Iranian art |

|---|

|

| Visual arts |

| Decorative arts |

| Literature |

| Performance arts |

| Other |

Iranian architecture displays great variety, both structural and aesthetic, from a variety of traditions and experience. Without sudden innovations, and despite the repeated trauma of invasions and cultural shocks, it has achieved "an individuality distinct from that of other Muslim countries".[3] Its paramount virtues are: "a marked feeling for form and scale; structural inventiveness, especially in vault and dome construction; a genius for decoration with a freedom and success not rivaled in any other architecture".[4]

Traditionally, the guiding formative motif of Iranian architecture has been its cosmic symbolism "by which man is brought into communication and participation with the powers of heaven".[5] This theme has not only given unity and continuity to the architecture of Persia, but has been a primary source of its emotional character as well.

According to American historian and archaeologist Arthur Pope, the supreme Iranian art, in the proper meaning of the word, has always been its architecture. The supremacy of architecture applies to both pre- and post-Islamic periods.[6]

Fundamental principles

Traditional Persian architecture has maintained a continuity that, although temporarily distracted by internal political conflicts or foreign invasion, nonetheless has achieved an unmistakable style.

In this architecture, "there are no trivial buildings; even garden pavilions have nobility and dignity, and the humblest caravanserais generally have charm. In expressiveness and communicativity, most Persian buildings are lucid, even eloquent. The combination of intensity and simplicity of form provides immediacy, while ornament and, often, subtle proportions reward sustained observation."[7]

Categorization of styles

Overall, the traditional architecture of the Iranian lands throughout the ages can be categorized into the six following classes or styles ("sabk"):[8]

- Zoroastrian:

- The Parsian style (up until the third century BCE) including:

- Pre-Parsian style (up until the eighth century BCE) e.g. Chogha Zanbil,

- Median style (from the eighth to the sixth century BCE),

- Achaemenid style (from the sixth to the fourth century BCE) manifesting in construction of spectacular cities used for governance and inhabitation (such as Persepolis, Susa, Ecbatana), temples made for worship and social gatherings (such as Zoroastrian temples), and mausoleums erected in honor of fallen kings (such as the Tomb of Cyrus the Great),

- The Parthian style includes designs from the following eras:

- The Parsian style (up until the third century BCE) including:

- Islamic:

- The Khorasani style (from the late 7th until the end of the 10th century CE), e.g. Jameh Mosque of Nain and Jameh Mosque of Isfahan,

- The Razi style (from the 11th century to the Mongol invasion period) which includes the methods and devices of the following periods:

- Samanid period, e.g. Samanid Mausoleum,

- Ziyarid period, e.g. Gonbad-e Qabus,

- Seljukid period, e.g. Kharraqan towers,

- The Azari style (from the late 13th century to the appearance of the Safavid Dynasty in the 16th century), e.g. Soltaniyeh, Arg-i Alishah, Jameh Mosque of Varamin, Goharshad Mosque, Bibi Khanum mosque in Samarqand, tomb of Abdas-Samad, Gur-e Amir, Jameh mosque of Yazd

- The Isfahani style spanning through the Safavid, Afsharid, Zand, and Qajarid dynasties starting from the 16th century onward, e.g. Chehelsotoon, Ali Qapu, Agha Bozorg Mosque, Kashan, Shah Mosque, Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque in Naqsh-i Jahan Square.

Materials

Available building materials dictate major forms in traditional Iranian architecture. Heavy clays, readily available at various places throughout the plateau, have encouraged the development of the most primitive of all building techniques, molded mud, compressed as solidly as possible, and allowed to dry. This technique, used in Iran from ancient times, has never been completely abandoned. The abundance of heavy plastic earth, in conjunction with a tenacious lime mortar, also facilitated the development and use of brick.[9]

Geometry

Iranian architecture makes use of abundant symbolic geometry, using pure forms such as circles and squares, and plans are based on often symmetrical layouts featuring rectangular courtyards and halls.

Design

Certain design elements of Persian architecture have persisted throughout the history of Iran. The most striking are a marked feeling for scale and a discerning use of simple and massive forms. The consistency of decorative preferences, the high-arched portal set within a recess, columns with bracket capitals, and recurrent types of plan and elevation can also be mentioned. Through the ages these elements have recurred in completely different types of buildings, constructed for various programs and under the patronage of a long succession of rulers.

The columned porch, or talar, seen in the rock-cut tombs near Persepolis, reappear in Sassanid temples, and in late Islamic times it was used as the portico of a palace or mosque, and adapted even to the architecture of roadside tea-houses. Similarly, the dome on four arches, so characteristic of Sassanid times, is a still to be found in many cemeteries and Imamzadehs across Iran today. The notion of earthly towers reaching up toward the sky to mingle with the divine towers of heaven lasted into the 19th century, while the interior court and pool, the angled entrance and extensive decoration are ancient, but still common, features of Iranian architecture.[7]

City design

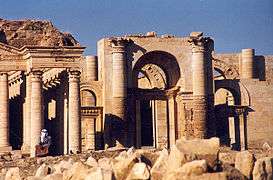

The circular city planning was a characteristic of several major Parthian and Sasanian cities, such as Hatra and Gor (Firuzabad). Another city design was based on a square geometry, found in the Eastern Iranian cities such as Bam and Zaranj.[10]

Pre-Islamic architecture of Persia

Hatra in Iraq. In the 3rd to 1st century BCE, during the Parthian Empire, Hatra was a religious and trading center. Today it is a World heritage site, protected by UNESCO.

Hatra in Iraq. In the 3rd to 1st century BCE, during the Parthian Empire, Hatra was a religious and trading center. Today it is a World heritage site, protected by UNESCO.- Dej-e Shapour-Khast

Sassanid Rayen Castle

Sassanid Rayen Castle

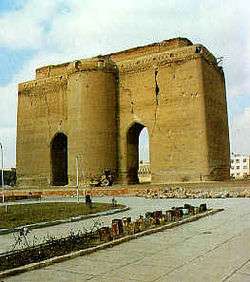

Arg-e Bam

Arg-e Bam

The pre-Islamic styles draw on 3000 to 4000 years of architectural development from various civilizations of the Iranian plateau. The post-Islamic architecture of Iran in turn, draws ideas from its pre-Islamic predecessor, and has geometrical and repetitive forms, as well as surfaces that are richly decorated with glazed tiles, carved stucco, patterned brickwork, floral motifs, and calligraphy.

Iran is recognized by UNESCO as being one of the cradles of civilization.[11]

Each of the periods of Elamites, Achaemenids, Parthians and Sassanids were creators of great architecture that, over the ages, spread far and wide far to other cultures. Although Iran has suffered its share of destruction, including Alexander The Great's decision to burn Persepolis, there are sufficient remains to form a picture of its classical architecture.

The Achaemenids built on a grand scale. The artists and materials they used were brought in from practically all territories of what was then the largest state in the world. Pasargadae set the standard: its city was laid out in an extensive park with bridges, gardens, colonnaded palaces and open column pavilions. Pasargadae along with Susa and Persepolis expressed the authority of 'The King of Kings', the staircases of the latter recording in relief sculpture the vast extent of the imperial frontier.

With the emergence of the Parthians and Sassanids new forms appeared. Parthian innovations fully flowered during the Sassanid period with massive barrel-vaulted chambers, solid masonry domes and tall columns. This influence was to remain for years to come.

For example, the roundness of the city of Baghdad in the Abbasid era, points to its Persian precedents, such as Firouzabad in Fars.[12] Al-Mansur hired two designers to plan the city's design: Naubakht, a former Persian Zoroastrian who also determined that the date of the foundation of the city should be astrologically significant, and Mashallah ibn Athari, a former Jew from Khorasan.[13]

The ruins of Persepolis, Ctesiphon, Sialk, Pasargadae, Firouzabad, and Arg-é Bam give us a distant glimpse of what contributions Persians made to the art of building. The imposing Sassanid castle built at Derbent, Dagestan (now a part of Russia) is one of the most extant and living examples of splendid Sassanid Iranian architecture. Since 2003, the Sassanid castle has been listed on Russia's UNESCO World Heritage list.

Islamic architecture of Persia

The fall of the Sassanian dynasty to the invading Muslim Arabs led to the adaptation of Persian architectural forms for Islamic religious buildings in Iran. Arts such as calligraphy, stucco work, mirror work and mosaics became closely tied with the architecture of mosques in Persia (Iran). An example is the round-domed rooftops which originate in the Parthian (Ashkanid) dynasty of Iran. Archaeological excavations have provided extensive evidence supporting the impact of Sassanid architecture on the architecture of the Islamic world at large.

The Razi style (شیوه معماری رازی) is a term for the used between the 11th century and the Mongol conquest of Iran, reflecting influences from Samanid, Ghaznavid, and Seljuk architecture.[14] Examples of the style include the Tomb of Isma'il of Samanid, Gonbad-e Qabus, the older parts of the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan and the Kharaqan towers.

Many experts believe the period of Persian architecture from the 15th through 17th centuries CE to be the pinnacle of the post-Islamic era. Various structures such as mosques, mausoleums, bazaars, bridges and palaces have survived from this period.

Safavid Isfahan tried to achieve grandeur in scale (Isfahan's Naghsh-i Jahan Square is the sixth largest square worldwide), by constructing tall buildings with vast inner spaces. However, the quality of ornaments was less compared to those of the 14th and 15th centuries.

Another aspect of this architecture was the harmony with the people, their environment, and the beliefs that it represented. At the same time no strict rules were applied to govern this form of Islamic architecture.

The great mosques of Khorasan, Isfahan and Tabriz each used local geometry, local materials and local building methods to express, each in their own way, the order, harmony, and unity of Islamic architecture. When the major monuments of Islamic Persian architecture are examined, they reveal complex geometrical relationships, a studied hierarchy of form and ornament and great depths of symbolic meaning.

In the words of Arthur U. Pope, who carried out extensive studies in ancient Persian and Islamic buildings:

The meaningful impact of Persian architecture is versatile. Not overwhelming but dignified, magnificent and impressive.

However, Pope's approach toward Qajar art and architecture is quite negative.[15]

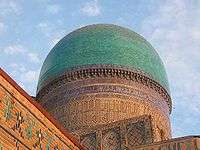

Persian domes

The Sassanid Empire initiated the construction of the first large-scale domes in Persia (Iran), with such royal buildings as the Palace of Ardashir and Dezh Dokhtar. After the Muslim conquest of the Sassanid Empire, the Persian architectural style became a major influence on Islamic societies and the dome also became a feature of Muslim architecture (see gonbad).

The Il-Khanate period provided several innovations to dome-building that eventually enabled the Persians to construct much taller structures. These changes later paved the way for Safavid architecture. The pinnacle of Il-Khanate architecture was reached with the construction of the Soltaniyeh Dome (1302–1312) in Zanjan, Iran, which measures 50 m in height and 25 m in diameter, making it the 3rd largest and the tallest masonry dome ever erected.[17] The thin, double-shelled dome was reinforced by arches between the layers.[18]

The renaissance in Persian mosque and dome building came during the Safavid dynasty, when Shah Abbas, in 1598, initiated the reconstruction of Isfahan, with the Naqsh-e Jahan Square as the centerpiece of his new capital.[19] Architecturally they borrowed heavily from Il-Khanate designs, but artistically they elevated the designs to a new level.

The distinct feature of Persian domes, which separates them from those domes created in the Christian world or the Ottoman and Mughal empires, was the use of colourful tiles, with which the exterior of domes are covered much like the interior. These domes soon numbered dozens in Isfahan and the distinct blue shape would dominate the skyline of the city. Reflecting the light of the sun, these domes appeared like glittering turquoise gems and could be seen from miles away by travelers following the Silk road through Persia.

This very distinct style of architecture was inherited from the Seljuq dynasty, who for centuries had used it in their mosque building, but it was perfected during the Safavids when they invented the haft- rangi, or seven colour style of tile burning, a process that enabled them to apply more colours to each tile, creating richer patterns, sweeter to the eye.[20] The colours that the Persians favoured were gold, white and turquoise patterns on a dark-blue background.[21] The extensive inscription bands of calligraphy and arabesque on most of the major buildings where carefully planned and executed by Ali Reza Abbasi, who was appointed head of the royal library and Master calligrapher at the Shah's court in 1598,[22] while Shaykh Bahai oversaw the construction projects. Reaching 53 meters in height, the dome of Masjed-e Shah (Shah Mosque) would become the tallest in the city when it was finished in 1629. It was built as a double-shelled dome, spanning 14 m between the two layers and resting on an octagonal dome chamber.[23]

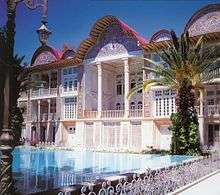

Persian Gardens: Khalvat-i Karim-khani, in the gardens of the Golestan Palace.

Persian Gardens: Khalvat-i Karim-khani, in the gardens of the Golestan Palace.

The mosque of Isfahan international conference center - modern architecture of dome.

The mosque of Isfahan international conference center - modern architecture of dome. Houses: The 18th century Abbasian House, Kashan.

Houses: The 18th century Abbasian House, Kashan. Towers and tombs: a design of the Seljuki era, Qazvin.

Towers and tombs: a design of the Seljuki era, Qazvin. Jamkaran Mosque.

Jamkaran Mosque. Gur Emir.

Gur Emir.

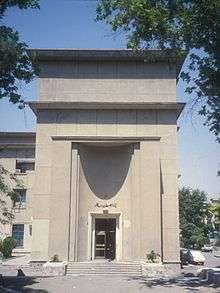

Contemporary Iranian architecture in and outside Iran

Contemporary architecture in Iran begins with the advent of the first Pahlavi period in the early 1920s. Some designers, such as Andre Godard, created works such as the National Museum of Iran that were reminiscent of Iran's historical architectural heritage. Others made an effort to merge the traditional elements with modern designs in their works. The Tehran University main campus is one such example. Others, such as Heydar Ghiai and Houshang Seyhoun, have tried to create completely original works, independent of prior influences.[24]Dariush Borbor's architecture successfully combined modern architecture with local vernacular.[25][26] Borj-e Milad (or Milad Tower) is the tallest tower in Iran and is the fourth tallest tower in the world.

.jpg) Iran Senate House Traditional Persian mythology such as the chains of justice of Nowshiravan and essences of Iranian architecture have been incorporated by Heydar Ghiai to create a new modern Iranian architecture.

Iran Senate House Traditional Persian mythology such as the chains of justice of Nowshiravan and essences of Iranian architecture have been incorporated by Heydar Ghiai to create a new modern Iranian architecture. Tehran's Museum of Contemporary Arts designed by Kamran Diba is based on traditional Iranian elements such as Badgirs, and yet has a spiraling interior reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim.

Tehran's Museum of Contemporary Arts designed by Kamran Diba is based on traditional Iranian elements such as Badgirs, and yet has a spiraling interior reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim. Tehran University College of Social Sciences shows obvious traces of architecture from Persepolis.

Tehran University College of Social Sciences shows obvious traces of architecture from Persepolis.

Future architecture in Iran

Major construction projects are underway all around Iran. Iran is developing Isfahan City Center, which is the largest mall in Iran and the largest mall with a museum in the world. It includes a hotel, indoor amusement park, and food court, among other amenities. The Flower of the East Development Project is another grand project on Kish Island in the Persian Gulf. The project, includes one '7-star' and two '5-star' hotels, three residential areas, villas and apartment complexes, coffee shops, luxury showrooms and stores, sports facilities and a marina.

Architectural style in Iranian Azerbaijan

The "Azerbaijani style" or "Azeri style" (Persian: شیوهٔ معماری آذری) is a style (sabk) of Iranian architecture developed in Iran's historic Azerbaijan region.[27]

Landmarks of this style of architecture span from the late 13th century (Ilkhanate) to the appearance of the Safavid Dynasty in the 16th century CE.[28] Chronologically the Azeri style is the fifth of the six historic styles of Iranian architecture, between the Razi style (from the 11th century to the Mongol invasion period) and the later Isfahani style.

Examples of this style are Dome of Soltaniyeh, Arg e Tabriz and Jameh Mosque of Urmia.[29]

Tekyeh Mir Chakhmagh, Yazd

Tekyeh Mir Chakhmagh, Yazd

Iranian architects

- See main articles: List of historical Iranian architects and List of Iranian architects

Persian architects were highly sought in the old days, before the advent of Modern Architecture. For example, Badreddin Tabrizi built the tomb of Rumi in Konya in 1273 AD, while Ostad Isa Shirazi is most often credited as the chief architect (or plan drawer) of the Taj Mahal.[30] These artisans were also highly instrumental in the designs of such edifices as Baku, Afghanistan's Minaret of Jam, The Sultaniyeh Dome, or Tamerlane's tomb in Samarkand, among many others.

UNESCO designated World Heritage Sites

The following is a list of World Heritage Sites designed or constructed by Iranians, or designed and constructed in the style of Iranian architecture:

- Inside Iran:

- Arg-é Bam Cultural Landscape, Kerman

- Naghsh-i Jahan Square, Isfahan

- Damavand, Mazandaran

- Pasargadae, Fars

- Persepolis, Fars

- Tchogha Zanbil, Khuzestan

- Takht-e Soleyman, West Azerbaijan

- Dome of Soltaniyeh, Zanjan

- Behistun Inscription

- Outside Iran:

- Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasavi, Kazakhstan

- Historic Centre of Baku

- Historic Centre of Ganja

- Historic Centre of Bukhara

- Historic Centre of Shahrisabz

- Itchan Kala of Khiva

- Samarkand - Crossroads of Cultures

- Citadel, Ancient City and Fortress Buildings of Derbent, Daghestan

- Baha'i Gardens

- Bibi-Heybat Mosque, Azerbaijan

- Tuba Shahi Mosque, Azerbaijan

- Palace of Shaki Khans, Sheki, Azerbaijan

Awards

- Several Iranian architects have managed to win the prestigious A’ Design Award 2018 in an unprecedented number of sections.[32]

- Mirmiran Architecture Award http://www.mirmiran-arch.org/

- The Memar Award: An award set for the best Architectural designs of the year in Iran

- Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

See also

- History of Iran

- Yakhchal

- Ab Anbar

- Windcatcher

- Great Wall of Gorgan

- Construction in Iran

- Architecture of Azerbaijan

- Islamic architecture

- Ottoman architecture

- Turkish architecture

- Mughal architecture

- ArchNet, MIT/UT Austin's archive of Iranian architectural documents

- Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran

- Band-e Kaisar

References

- "'برج آزادی پس از۲۰ سال شسته می شود'". BBC News فارسی (in Persian). Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- Arthur Upham Pope. Introducing Persian Architecture. Oxford University Press. London. 1971. p.1

- Arthur Upham Pope. Persian Architecture. George Braziller, New York, 1965. p.266

- Arthur Upham Pope. Persian Architecture. George Braziller, New York, 1965. p.266

- Nader Ardalan and Laleh Bakhtiar. Sense of Unity; The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture. 2000. ISBN 1-871031-78-8

- Arthur Pope, Introducing Persian Architecture. Oxford University Press. London. 1971.

- Arthur Upham Pope. Persian Architecture. George Braziller, New York, 1965. p.10

- Sabk Shenasi Mi'mari Irani (Study of styles in Iranian architecture), M. Karim Pirnia. 2005. ISBN 964-96113-2-0 p.24. Page 39 however considers "pre-Parsi" as a distinct style.

- Arthur Upham Pope. Persian Architecture. George Braziller, New York, 1965. p.9

- Jayyusi, Salma K.; Holod, Renata; Petruccioli, Attilio; Raymond, Andre (2008). The City in the Islamic World, Volume 94/1 & 94/2. BRILL. pp. 173–176. ISBN 9789004162402.

- Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter (2000). Islam Art and Architecture. p. 96. ISBN 3-8290-2558-0.

- Hill, Donald R. (1994). Islamic Science and Engineering. p. 10. ISBN 0-7486-0457-X.

- Sabk Shenasi Mi'mari Irani (Study of styles in Iranian architecture), M. Karim Pirnia. 2005. ISBN 964-96113-2-0; Siddiq-a-Akbar, Aptul Rakumāṉ, Muhammad Ali Tirmizi, Sultanate period architecture: proceedings of the Seminar on the Sultanate Period Architecture in Pakistan, held in Lahore, November 1990, P 179; Fallahfar, Saeed (سعید فلاحفر). Dictionary of Traditional Iranian Architecture (فرهنگ واژههای معماری سنتی ایران). Kamyab Publications. Edition 1. Tehran. 2000. ISBN 964-350-316-X pp.106 ((2nd print))

- Hassan Pour (2013). "The Theoretical Inapplicability of Regionalism to Analysing Architectural Aspects of Islamic Shrines in Iran in the Last Two Centuries" [کاربست ناپذیری نظری رجینالیسم در تحلیل معماری اسلامی ایران در دو قرن گذشته] (PDF). The Collection of Articles of the International Congress of Imam's Descendants (Imamzadegan). Esfahan, Iran: The Charity Organisation. 4: 16–32.

- "Imam's Mosque". World-heritage-tour.org. 2005-03-12. Archived from the original on 2011-05-19. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- "Encyclopædia Iranica | Articles". Iranicaonline.org. 1995-12-15. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- Savory, Roger (1980). Iran under the Safavids. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-521-22483-7.

- Blake, Stephen P. (1999). Half the World, The Social Architecture of Safavid Isfahan, 1590–1722. Costa Mesa: Mazda. pp. 143–144. ISBN 1-56859-087-3.

- Canby, Sheila R. (2009). Shah Abbas, The Remaking of Iran. London: British Museum Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7141-2456-8.

- Canby, Sheila R. (2009). Shah Abbas, The Remaking of Iran. p. 36.

- Hattstein, M.; Delius, P. (2000). Islam, Art and Architecture. Cologne: Köneman. pp. 513–514. ISBN 3-8290-2558-0.

- Trends in Modern Iranian Architecture. By Darab DIBA and Mozayan DEHBASHI.

- Architecture: formes + fonctions. =Books.google.com. 2010-11-10. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- Michel Ragon, Histoire Mondiale de l'Architecture et de l'Urbanisme Modernes, vol. 2, Casterman, Paris, 1972, p. 356.

- Ajorloo, Bahram (1 June 2010). "abstract, An Introduction to the Azerbaijani Style of Architecture". Bagh- e Nazar: The Scientific Journal of Nazar Research Center, for Art, Architecture & Urbanism. 7 (14). Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- Fallāḥʹfar, Saʻīd (سعید فلاحفر). The Dictionary of Iranian Traditional Architectural Terms (Farhang-i vāzhahʹhā-yi miʻmārī-i sunnatī-i Īrān فرهنگ واژههای معماری سنتی ایران). Kamyab Publications (انتشارات کامیاب). Kāvoshʹpardāz. 2000, 2010. Tehran. ISBN 978-964-2665-60-0 US Library of Congress LCCN Permalink: http://lccn.loc.gov/2010342544 pp.16

- Sabk Shenasi Mi'mari Irani (Study of styles in Iranian architecture), M. Karim Pirnia. 2005. ISBN 964-96113-2-0 pp.204-205

- See PBS article

- Arthur Upham Pope, Persian Architecture, 1965, New York, p.16

- http://ifpnews.com/exclusive/iranian-architects-among-winners-of-prestigious-a-design-award-2018/ "Iranian Architects among Winners of Prestigious A’ Design Award 2018"

- Aga Khan Award for Architecture - Master Jury Report - The Eighth Award Cycle, 1999-2001 Archived 2007-06-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Aga Khan Award for Architecture: The Third Award Cycle, 1984-1986 Archived 2007-05-12 at the Wayback Machine

- (AKTC) Archived 2007-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Carboni, S.; Masuya, T. (1993). Persian tiles. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Abdullahi Y.; Embi M. R. B (2015). Evolution Of Abstract Vegetal Ornaments On Islamic Architecture. International Journal of Architectural Research: Archnet-IJAR.

- Yahya Abdullahi; Mohamed Rashid Bin Embi (2013). "Evolution of Islamic geometric patterns". Frontiers of Architectural Research. Frontiers of Architectural Research: Elsevier. 2 (2): 243–251. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2013.03.002.

- Encyclopedia Iranica on ancient Iranian architecture

- Encyclopedia Iranica on Stucco decorations in Iranian architecture

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of Iran. |

.jpeg)