Hohenzollern Castle

Hohenzollern Castle (German: ![]()

| Hohenzollern Castle | |

|---|---|

German: Burg Hohenzollern | |

Hohenzollern Castle, Summer 2005 | |

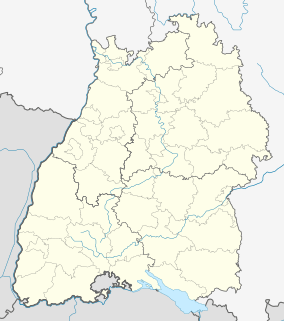

Hohenzollern Castle Location within Baden-Württemberg | |

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type | Palace, Castle |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

| Town or city | Bisingen, Zollernalbkreis |

| Country | Germany |

| Coordinates | 48°19′23.5″N 8°58′3.8″E |

| Elevation | 855 meters (2,805 ft) (NHN) |

| Named for | House of Hohenzollern |

| Owner | Georg Friedrich, Prince of Prussia (3/4) Karl Friedrich, Prince of Hohenzollern (1/4) |

| Affiliation | House of Hohenzollern |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Friedrich August Stüler |

| Website | |

| www | |

The first castle on the mountain was constructed in the early 11th century. Over the years the House of Hohenzollern split several times, but the castle remained in the Swabian branch, the dynastic seniors of the Franconian-Brandenburgian cadet branch that later acquired its own imperial throne. This castle was completely destroyed in 1423 after a ten-month siege by the free imperial cities of Swabia.

The second castle, a larger and sturdier structure, was constructed from 1454 to 1461, which served as a refuge for the Catholic Swabian Hohenzollerns, including during the Thirty Years' War. By the end of the 18th century it was thought to have lost its strategic importance and gradually fell into disrepair, leading to the demolition of several dilapidated buildings.

The third, and current, castle was built between 1846 and 1867 as a family memorial by Hohenzollern scion King Frederick William IV of Prussia. Architect Friedrich August Stüler based his design on English Gothic Revival architecture and the Châteaux of the Loire Valley.[1] No member of the Hohenzollern family was in permanent or regular residence when it was completed, and none of the three German Emperors of the late 19th and early 20th century German Empire ever occupied the castle; in 1945 it briefly became the home of the former Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany, son of the last Hohenzollern monarch, Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Among the historical artifacts of Prussian history contained in the castle are the Crown of Wilhelm II, some of the personal effects of King Frederick the Great, and a letter from US President George Washington thanking Hohenzollern descendant Baron von Steuben for his service in the American Revolutionary War.[2]

Geography

Hohenzollern Castle is a hilltop castle located on the Berg Hohenzollern, an isolated promontory of the Swabian Jura 855 meters (2,805 ft) (NHN) above sea level, 234 meters (768 ft) above and to the south of Hechingen, Germany approximately 50 kilometers (31 mi) south of Stuttgart, capital of Baden-Württemberg.[3] This mountain lends its name to the local geographic region, der Zollernalbkreis, and is known among locals as Zollerberg (Zoller Mountain), or simply Zoller.

History

First and Second castles

Only written records exist of the original castle built in the High Middle Ages, built by the Counts of Zollern. Although the House of Hohenzollern itself finds its first mention in 1061,[lower-alpha 2] the castle is first mentioned as "Castro Zolre" in 1267, without any mention of the castle beyond its name, though contemporary sources praised it as the "crown of all castles in Swabia."[5] In 1423 the castle was totally destroyed[6] after a year-long siege by the Swabian League of Cities.

Construction on a second, stronger castle began in 1454.[6] It was captured by Württemberger troops in 1634 midway in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), then fell under Habsburg control for about a century. During the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748) it was occupied in the winter of 1744/45 by French soldiers. Returned to Habsburg control after the war, it was rarely occupied and began to fall to ruin after the last Austrian owner left the castle in 1798. By the beginning of the 19th century only the Chapel of St. Michael remained usable.

Third castle

The current castle was built by Hohenzollern scion Crown-Prince Frederick William IV of Prussia. Traveling through southern Germany en route to Italy in 1819 he wished to learn about his family's roots, so climbed to the top of Mount Hohenzollern. He would write in 1844 as King:[7]

The memory of the year [18]19, to me is exceedingly lovely, and like a beautiful dream, especially the sunset we saw from one of the castle bastions. [...] Now is a desire, a dream of [my] youth, to see Hohenzollern Castle again made habitable.

He engaged Friedrich August Stüler,[8] who had been appointed Architect of the King for the rebuilding of Stolzenfels Castle in 1842 while still a student and heir of Karl Friedrich Schinkel, to design a new castle. Stüler began work on an ornate design influenced by English Gothic Revival architecture and the Châteaux of the Loire Valley[1] in 1846. The impressive entryway is the work of the Engineer-Officer Moritz Karl Ernst von Prittwitz, considered the leading fortifications engineer in Prussia. The sculptures around and inside the castle are the work of Gustav Willgohs. Like Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, Hohenzollern Castle is a monument to German Romanticism which incorporated an idealized vision of a medieval knight's castle. Lacking some of the fantastic elements and excesses of Neuschwanstein, the castle's construction served to enhance the reputation of the Prussian Royal Family.

Construction began in 1850,[9] and was funded entirely by the Brandenburg-Prussian and the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen lines of the Hohenzollern family. Construction was completed on 3 October 1867, under Frederick William IV's brother King William I.

After the castle was rebuilt, it was not regularly occupied, but rather used primarily as a showpiece. None of the Hohenzollern Kaisers of the German Empire lived there; only the last Prussian Crown Prince William stayed for several months following his flight from Potsdam ahead of Soviet army forces during the closing months of World War II. He and his wife Crown Princess Cecilie are buried there, as the family's estates in Brandenburg had been occupied by the Soviet Union at the time of their deaths.

Starting in 1952, Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia began adding valuable artwork and Prussian memorabilia[5] from the collections of the Hohenzollern family and the former Hohenzollern Museum in Schloss Monbijou. Two of the major pieces are the Crown of Wilhelm II and a uniform that belonged to King Frederick the Great. From 1952 until 1991 the caskets of Frederick Wilhelm I and his son Frederick the Great were in the chapel, but were moved back to Potsdam following German reunification in 1991.

The castle was damaged in an earthquake on 3 September 1978,[10] and was under repair until the mid-1990s.

Today

.jpg)

With over 350,000 visitors per year Hohenzollern castle is one of the most visited castles in Germany.[11] The castle is privately owned by the House of Hohenzollern,[12] with two-thirds belonging to the Brandenburg-Prussian branch, and the balance to the Swabian branch. Since 1952, the Princess Kira of Prussia Foundation has used the castle for an annual summer camp for children.[13] Whenever Prince George and his family are staying at the castle, the Prussian flag flies over the castle.[12]

In 2015, parts of the 2016 thriller-horror film A Cure for Wellness were filmed at the castle,[14][15] closing it from 13–24 July 2015.[16] Hohenzollern Castle as well as Peckforton Castle in England were also used in the filming of the 2017 TV adaption of The Worst Witch.[17][18]

Architecture

Hohenzollern Castle, covering almost all of Mount Hohenzollern's summit, is a structure composed of four primary parts: military architecture, the palatial buildings, chapels, and the gardens.

Military architecture

The Eagle Gate (German: Adlertor) and its attached drawbridge form the entrance to the castle. The castle's winding zwinger turns four times and terminates in the bastions. From here, the palatial buildings can be accessed through the square upper gate and so are the rest of the bastions.

Palatial buildings

The palace itself, sitting upon the outline of the second castle, is an open-air museum arranged in a u-shape that ends with Protestant and Catholic chapels. Sitting on top of the old casemates are the three story Gothic Revival buildings of Friedrich August Stüler's design, decorated with towers and pinnacles. The four towers of the palace are aligned to the bastions, with the Emperor's Tower to the Fuchsloch bastion, Bishop's Tower to the Spitz bastion, Markgraf Tower to the Scharfeck bastion, and Michael's Tower to the garden bastion. Attached to the main residential building, the Count's Hall, is the final tower, the Watch Tower (German: Wartturm), which functions both as a staircase to the library and as the flag pole whenever the Hohenzollern family is residing in the castle.

Interiors

A perron leads up to the ancestry hall, where one enters the Count's Hall (German: Grafensaal), which covers the entirety of the southern wing. The rib vaulting of the Count's Hall, adorned with grisailles by Stüler depicting the history of the House of Hohenzollern and pointed-arch windows, is supported by eight free standing red marble columns. Below the Count's Hall is the old castle kitchen, today a treasure chamber. Next to the Count's Hall is the Emperor's Tower and the Bishop's Niche, following the library decorated with murals of the Hohenzollern history by Wilhelm Peters. The Margrave's Tower contains the King's parlor, also referred to as the Margrave's room, contrary to Stüler's terminology.

Burials

- William, German Crown Prince

- Duchess Cecilie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin[2]

- Grand Duchess Kira Kirillovna of Russia, in the castle cemetery

- Louis Ferdinand, Prince of Prussia, in the castle cemetery

- Princess Kira of Prussia, in the castle cemetery

- Prince Hubertus of Prussia, in the castle cemetery

- Princess Alexandrine of Prussia (1915–1980), in the castle cemetery

See also

Notes

- The House of Hohenzollern emerged in the Middle Ages and produced the three German emperors of the German Empire in late 19th and the early 20th centuries.

- Berthold of Reichenau writes in a chronicle in 1061 that Wezil and Burchardus "de Zolorin" were killed in battle.[4]

Citations

- Herbert Gers. Hohenzollern Castle. 5th ed. Hechingen: Administration of Hohenzollern Castle, 1984.

- Hays 2014, p. Hohenzollern Castle.

- "Hohenzollern Castle, Germany". youramazingplaces.com. Your Amazing Places.

- Official Website: Family History

- Hendrix 2012, p. 17.

- Official Website: Castle History

- Die Erinnerung vom J. 19 ist mir ungemein lieblich und wie ein schöner Traum, zumal der Sonnenuntergang, den wir von einer der Schloßbastionenen aus sahen. [...] Nun ist ein Jugendtraum-Wunsch, den Hohenzollern wieder bewohnbar gemachet zu sehen.. Kennzeichen BL Heimatkunde für den Zollernalbkreis; eds. Waldemar Lutz, Jürgen Nebel, Hansjörg Noe; Lörrach, Stuttgart, 1987 ISBN 3-12-258310-0; p. 121f.

- Taylor 2009, p. Burg Hohenzollern.

- Katritzki 2005, p. 50.

- "Damage Heavy As Big Quake Rocks Germany". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Google news. UPI. 4 September 1978. p. 2. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- Germany Travel: Hohenzollern Castle, "Life-saving snuff box, gold and silver"

- Germany Travel: Hohenzollern Castle, "Privately owned for 1,000 years"

- Preussen.de: George Frederick The Prince of Prussia

- "Castle Hohenzollern plays backdrop for a movie". Deutsche Welle. 15 March 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Architectural Digest: How A Cure for Wellness Marries Horror and Beauty in Set Design, 14 February 2017

- Brenner, Julia. "Regisseur Gore Verbinski dreht Horrorfilm auf Burg Hohenzollern" (in German). Schwarzwälder Bote.

- BBC: Top 15 facts about The Worst Witch – Media Centre, 11 December 2016

- BBC: Cast announced as production begins on CBBC's adaptation of The Worst Witch, 16 May 2016

References

- Hays, Charles (3 October 2014). Old Soldiers. Xlibris. ISBN 9781499066937.

- Hendrix, Joseph B. (12 September 2012). Through The Eye of My Lens. AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781477272800.

- Katritzki, Freda (15 October 2005). The World of Private Castles, Palaces and Estates. Chateaux Prives. ISBN 9782952414210.

- Taylor, Robert R. (4 August 2009). The Castles of the Rhine: Recreating the Middle Ages in Modern Germany (Illustrated, revised ed.). Wilfrid Laurier University Press Press. ISBN 9781554588015.

Further reading

- Rolf Bothe: Burg Hohenzollern. Von der mittelalterlichen Burg zum nationaldynastischen Denkmal im 19. Jahrhundert. Berlin 1979, ISBN 3-7861-1148-0

- Ulrich Feldhahn (Hg.): Beschreibung und Geschichte der Burg Hohenzollern. Berlin Story Verlag, Berlin, 1.Auflage 2006, ISBN 3-929829-55-X

- Patrick Glückler: Burg Hohenzollern. Kronjuwel der Schwäbischen Alb. Hechingen 2002; 127 Seiten; ISBN 3-925012-34-6

- Rudolf Graf von Stillfried-Alcantara: Beschreibung und Geschichte der Burg Hohenzollern. Nachdruck der Ausgabe von 1870. Berlin Story Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-929829-55-X

- Friedrich Hossfeld und Hans Vogel: Die Kunstdenkmäler Hohenzollerns, erster Band: Kreis Hechingen. Holzinger, Hechingen 1939, S. 211 ff.

News sources

- "Top 15 facts about The Worst Witch". The Media Centre. British Broadcasting Company. BBC. 11 December 2016.

- "Cast announced as production begins on CBBC's adaptation of The Worst Witch". The Media Centre. British Broadcasting Company. BBC. 16 May 2016.

- Minton, Melissa (14 February 2017). "How A Cure for Wellness Marries Horror and Beauty in Set Design". Architectural Digest.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Burg Hohenzollern. |

- "Official Website (Start page)". burg-hohenzollern.com. Hohenzollern Castle, Family.

- "Hohenzollern Castle". germany.travel/en/index.html. Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy.

- "Official Website of the House of Hohenzollern". preussen.de/en. House of Hohenzollern.

.svg.png)