Building a Gothic cathedral

Building a Gothic cathedral was the most ambitious, expensive, and technically demanding construction project of the Middle Ages. It required high-level sponsorship, substantial funding over decades, a large number of highly skilled workers, and finding solutions to unprecedented and very complex technical problems. Completion of a cathedral usually took at least half a century, and many took much longer, involving several generations of architects and workers. Since the construction took so long and was so expensive, Portions of many cathedrals were built in several successive styles, and many were left unfinished.

Motivation

The period from the 11th to 13th century brought unprecedented population growth and prosperity to northern Europe, particularly to the large cities, and particularly to those cities on trading routes.[1] The old Romanesque cathedrals were too small for the population, and city leaders wanted visible symbols of their new wealth and prestige. The frequent fires in old cathedrals were also a frequent reason for constructing a new building, as at Chartres Cathedral, Rouen Cathedral, Bourges Cathedral, and numerous others.[1]

Finance

The Bishop himself, like Maurice de Sully of Notre Dame de Paris, usually contributed a substantial sum. Wealthy parishioners were invited to give a percentage of their income or estate in exchange for the right to be buried under the floor of the cathedral. In 1263 Pope Urban IV offered Papal indulgences, or the forgiveness of sins for one year, to wealthy donors who made large contributions.[2] For less wealthy church members, contributions in kind, such as a few days labor,the use of their of oxen for transportation, or donations of materials were welcomed. The sacred relics of Saints kept by the cathedral were displayed to attract pilgrims, who were invited to make donations. Sometimes the relics were taken in a procession to other towns to raise money.[2]

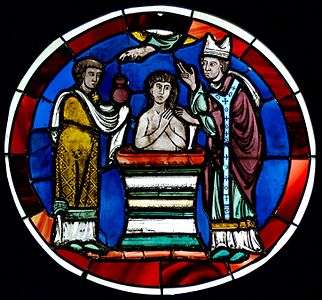

The guilds of the various professions in the town, such as the bakers, fur merchants and drapers, frequently made donations, and in exchange small panels of the stained glass windows in the new cathedral windows illustrated their activities.[3]

The Master Builder

The key figure in the construction of a Cathedral was the Master Builder or Master Mason, who was the architect in charge of all aspects of the construction. One example was Gautier de Varinfroy, Master Builder of Evreaux Cathedral. His contract, signed in 1253 with the Master of the Cathedral and Chapter of Evreux, paid him fifty pounds a year. He was required to live in Evreux, and to never be absent from the construction site for more than two months.[4]

The Master Masons were members of a particularly influential guild, the Corporation of Masons, the best-organized and most secretive of the Medieval guilds.[5] The names of the Master Masons of Early Gothic architecture are sometimes unknown, but later Master Masons, such as Godwin Gretysd, builder of Westminster Abbey for King Edward the Confessor, and Pierre de Montreuil, who worked on Notre Dame de Paris and the Basilica of Saint-Denis, became very prominent. Eudes de Montreuil, the Master Mason for Louis IX of France, advised him on all architectural matters, and accompanied the King on the Crusades. The profession was frequently passed from father to son. The most famous family of Cathedral-builders was that of Peter Parler, born in 1325, who worked on Prague Cathedral, and was followed in his position by his son and grandson. The Parlers'work influenced European cathedrals as far away as Spain.[5] Master Masons frequently traveled to see other projects, and consulted with one another on technical issues. They also became wealthy. While the salary of an average mason or carpenter was the equivalent of twelve English pounds a year, the Master Mason William Wynford received the equivalent of three thousand pounds a year.[5]

The Master Mason was responsible for all aspects of the building site, including preparing the plans, selecting the materials, coordinating the work of the craftsmen, and paying the laborers. He also needed a substantial knowledge of theology, as he had to consult regularly with the Bishop and Canons about the religious functions of the building. The epitaph of the Master Mason Pierre de Montreuil of Notre Dame de Paris described him appropriately as a "Doctor of stones". The tomb of Hugues Libergier, Master Mason of Reims Cathedral, also depicts him in the robes of a Doctor of theology.[6]

The Plans

The Master Mason usually first made a model of the building, either of papier-mâché, wood, plaster or stone, to explain the building to the Bishop and Canons. When the plan was approved,it was very difficult to make multiple large scale drawings, because parchment was expensive and usually scrubbed off and reused, and printing on a large scale was not yet possible. The plans for each section were usually drawn on the floor or on large panels in the workshop of the Master builder, where they could be consulted.[7] The original plans of Prague Cathedral were rediscovered in the 19th century and use to complete the building.[6]

Materials

Building a cathedral required enormous quantities of stone, as well as timber for the scaffolding and iron for reinforcement. Sometimes stone from earlier ruined buildings was recycled, as at Beauvais Cathedral,[8] but usually new stone had to be quarried, and in most cases the quarries were a considerable distance from the Cathedral site. In a few cases, such as Lyon and Chartres Cathedrals, the quarries were owned by the Cathedral. In other cases, such as Tours Cathedral and Amiens Cathedral, the builders purchased the rights to extract all the stone needed from a quarry for certain period of time.[8] The stones were usually extracted and roughly trimmed at the quarry, and then shipped, by road or preferably by barge or ship, which was much less expensive, to the building site. For some early English cathedrals, the stone was shipped from Normandy, whose quarries produced an exceptionally fine pale-coloured stone.[9]

The preferred building stone in the Ile-de-France was limestone. As soon as they were cut, the stones gradually developed a coating of calcination, which protected them. The stone was carved at the quarry so the calcination could develop. then shipped to the building site.[10] When the facade of Notre-Dame de Paris was cleaned of soot and grime in the 1960s, the original white color was exposed.

On land, stones were often moved by oxen; some shipments required as many as twenty teams of two oxen each. The oxen were particularly important in the construction of Laon Cathedral, moving the all stones to the top of a steep hill. They were honored for their work by statues of sixteen oxen placed on the towers of the Cathedral.[8]

Each stone at the construction site carried three marks, placed on the side which would not be visible in the finished cathedral. The first indicated its quarry of origin; the second indicated the position of the stone and the direction it should face; and the third was the signature mark of the stone carver, so the Master Mason could evaluate the quality. These marks allowed modern historians to trace the work of individual stone carvers from Cathedral to Cathedral.[8]

An enormous amount of wood was consumed in Gothic construction for scaffolding, platforms, hoists, beams and other uses. They particularly consumed durable hard woods such as oak and walnut. This led to a shortage of these trees, and eventually led to the practice of using softer pine for scaffolds, and reusing old scaffolding from worksite to worksite.[8]

A large amount of iron was also used in early Gothic for the reinforcement of walls, windows and vaults. It was soon discovered that the iron rusted and deteriorated, causing walls to fail, so it was gradually replaced by other more durable forms of support, such as the flying buttress.[11] The most visible use of iron was to reinforce the glass of rose windows and other large stained glass windows, making possible their enormous size (fourteen meters in diameter at Strasbourg Cathedral) and their intricate designs.[12]

As the period advanced, the materials gradually became more standardized, and certain parts, such as columns and cornices and building blocks, could be produced in series for use at multiple sites.[13] Full-size templates were used to make complex structures such as vaults or the pieces of ribbed columns, which could be reused at different sites.[14] The result of these efforts was a remarkable degree of precision. The stone pillars of the triforium of the apse of Chartres Cathedral have a maximum variation of plus or minus 19 millimetres.[15] Excess materials and stone chips were not wasted. Instead of building walls of solid stone, walls were often built with two smooth stone faces filled in the interior with stone rubble.[14]

Construction site

Cathedrals were traditionally built from east to west. If the new building was replacing an older cathedral, the choir at the east end of the old cathedral was demolished first, to begin construction of the new building, while the nave to the west was left standing for religious services. Once the new choir was completed and sanctified, the rest of the old cathedral was gradually torn down. The walls and pillars, timber scaffolding and roof were built first. Once the roof was in place, and the walls were reinforced with buttresses, the construction of the vaults could begin.[16]

One of the most complex steps was the construction of the rib vaults, which covered the nave and choir. Their slender ribs directed the weight of the vaults to thin columns leading down to the large support pillars below. The first step in the construction of a vault was the construction of a wooden scaffold up to the level of the top of the supporting columns. Next, a precise wooden frame was constructed on top of the scaffold in the exact shape of the ribs. The stone segments of the ribs were then carefully laid into the frame and cemented. When the ribs were all in the place, the keystone was placed at the apex where they converged. Once the keystone was in place, the ribs could stand alone, Workers then filled in the compartments between the ribs with a thin layer of small fitted pieces of brick or stone. The framework was removed. Once the compartments were finished, their interior surface, visible from below, was plastered and then painted, and the vault was complete.[17]

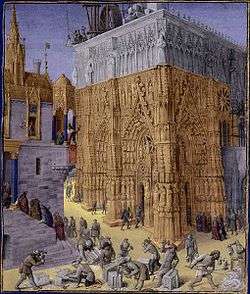

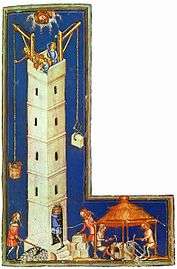

Dagobert visiting the construction site of Saint-Denis "Les Grandes Chroniques de France". 15th century, Bibliothèque nationale de France

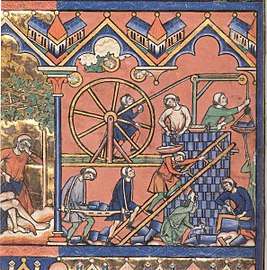

Dagobert visiting the construction site of Saint-Denis "Les Grandes Chroniques de France". 15th century, Bibliothèque nationale de France A treadmill crane (13th century)

A treadmill crane (13th century) "Reconstruction of the Temple in Jerusalem", Rouen, 15th century

"Reconstruction of the Temple in Jerusalem", Rouen, 15th century

This process required a team of specialized workers. This included the hewers who cut the stone, the posers who set the stones in place; and layers who cemented the pieces together. These craftsmen worked alongside the carpenters who built the complex scaffolds and models.[17]

Work continued six days a week, from sunrise until sundown, except Sundays and religious holidays.[16]

The stones were finished at the site and put into place, following the drawings by the Master Mason displayed in his workshop on the site, or sometimes inscribed on the floor of the Cathedral itself. Some of these plans can still be seen on the floor of Lyon Cathedral.[12]

Since the Gothic cathedrals were the tallest buildings built in Europe since the Roman Empire, new technologies were needed to lift the stones up to the highest levels. A variety of cranes were developed. These included the treadmill crane, a hoist powered by one or more men walking inside a large wheel called an "ecureuil", or "squirrel". The wheel varied in size from 2.5 meters to 8 meters, and allowed a single man to hoist a weight of up to 600 kilograms.[12]

During the winter, the construction on the site was usually shut down. To prevent the rain or snow from damaging the unfinished masonry, it was usually covered with fertiliser. Only the sculptors and stone-cutters, in their workshops, were able to continue work.[16]

_29.jpg) Hoists and stone cutters (15th century)

Hoists and stone cutters (15th century) Construction site of Saint-Jacques de Compostelle (16th century)

Construction site of Saint-Jacques de Compostelle (16th century)_-_Elijah_Begging_for_Fire_from_Heaven_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Scaffolds and hoists, Flemish (about 1541)

Scaffolds and hoists, Flemish (about 1541)

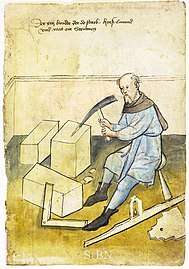

Workmen

The stone-cutters, mortar-makers, carpenters and other workers were highly skilled but usually illiterate. They were managed by foremen who reported to the Master Mason. The foremen used tools such as the compass to measure and enlarge the plans to full size. and levels using lead in glass tubes to assure and the blocks were level, The stone dressers used similar tools to make sure the surfaces were flat and the edges were at precise right angles.[18] Their tools were frequently shown in the Medieval miniature drawings of the period (see gallery).

Porters carrying stone depicted in window of Bourges Cathedral

Porters carrying stone depicted in window of Bourges Cathedral Stone cutter, Nuremburg, (1425)

Stone cutter, Nuremburg, (1425) A stone cutter and his tools, Nuremberg (1585)

A stone cutter and his tools, Nuremberg (1585) Stone cutter, Nuremburg (1457)

Stone cutter, Nuremburg (1457)

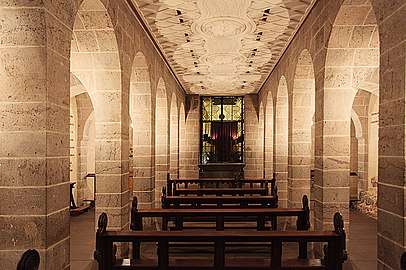

Below ground - the Crypt

The Crypt, or underground vault, was usually part of the foundation of the building, and was built first. Many Gothic Cathedrals, like Notre Dame de Paris and Chartres, were built on the sites of Romanesque cathedrals, and often used the same foundations and crypt. In Romanesque times the crypt was used to keep sacred relics, and often had its own chapels and, as in the 11th century crypt of the first Chartres Cathedral, a deep well. The Romanesque crypt of Chartres Cathedral was greatly enlarged in the 11th century; it is U-shaped and 230 meters long. It survived the fire in the 12th century which destroyed the Romanesque cathedral, and was used as the foundation for the new Gothic Cathedral. The walls of the crypt chapels were painted with Gothic murals. The names of the Master Masons were frequently inscribed on the walls of Cathedral crypts.[19]

A chapel with murals in the Romanesque-Gothic crypt of Chartres Cathedral (11th-13th century)

A chapel with murals in the Romanesque-Gothic crypt of Chartres Cathedral (11th-13th century) Romanesque-Gothic crypt of Rochester Cathedral (12th century)

Romanesque-Gothic crypt of Rochester Cathedral (12th century) Crypt of Cologne Cathedral

Crypt of Cologne Cathedral- Crypt of Strasbourg Cathedral

Windows and stained glass

The stained glass windows were an essential element of the Cathedral, filling the interior with coloured light. They grew larger and larger over the course of the Gothic period, until the filled the entire walls beneath the vaults. In the early Gothic period the windows were relatively small, and the glass was thick and densely colored, giving the light a mysterious quality which contrasted strongly with the dark interiors. In the later period, the builders installed much larger windows, and frequently used grey-or white colored glass, or grisaille, which made the interior much brighter.

The windows themselves were made by two different groups of craftsmen, usually at different locations. The colored glass was made at workshops located near forests, because an enormous amount of firewood was needed to melt the glass. The molten glass was colored with metal oxides, and then blown into a bubble, which was cut and flattened into small sheets.[20]

The glass sheets were then transferred to the workshop of the window-maker, usually close to the Cathedral site. There a full-size precise drawing of the window was made on a large table, with the colors indicated. The craftsmen cracked off off small pieces of colored glass to fill in the design. When it was complete, the pieces of glass were fit into slots of thin lead strips, and then the strips were soldered together. The faces and other details were painted onto the glass in vitreous enamel colors, which were fired in a kiln to fuse the paint to the glass. The sections were and fixed into the stone mullions of the window. and reinforced with iron bars.[20]

In the later Gothic periods the windows were larger and were painted with more sophisticated techniques. They were sometimes covered with a thin layer of colored glass, and this layer was carefully scratched to achieve finer shading, giving the images greater realism. This was called flashed glass. Gradually the windows came more and more to resemble paintings, but lost some of the vivid contrast and richness of color of early Gothic glass.[20]

- Detail of a Tree of Jesse from York Minster (c. 1170), the oldest stained-glass window in England.

- 13th century window from Chartres Cathedral. Cobalt blue and borders of red flashed glass

Rayonnant glass from Sainte-Chapelle (13th century)

Rayonnant glass from Sainte-Chapelle (13th century)

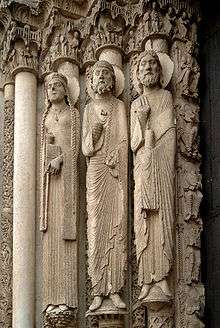

Sculpture

Sculpture was an essential element of the Gothic cathedral. Its purpose was to illustrate the personages, stories and messages of the Bible to the ordinary church-goers, of whom the great majority were illiterate.[21] It had been used in the tympana of Romanesque churches, but in Gothic architecture it gradually spread across the entire facade and the transepts, and even the interior of the facade.

The sculptors did not select the subject matter of their work. Church doctrine specified that the themes would be specified by the church fathers, not the artists.[22] Nonetheless, the Gothic artists over time began to add figures with increasingly realistic features and expressive faces, and gradually the statues became more lifelike and separate from the walls.

An early innovative feature used by Gothic sculptors was the statue-column. At the Basilica of Saint-Denis, twenty statues of the apostles supported the central portal, literally portraying them as "pillars of the church."[23] The originals were destroyed during the French Revolution, and only fragments remain. The idea was quickly adapted for the west porch of Chartres Cathedral (about 1145), possibly by the same sculptors.[23]

Traces of paint on sculpture of the portals shows that they were originally painted in bright colors, each color having a particular theological significance. This effect is now recreated today at Amiens with the use of colored light.

Statue-columns of Old Testament figures, west porch of Chartres Cathedral (1145-55)

Statue-columns of Old Testament figures, west porch of Chartres Cathedral (1145-55)- Portals of Amiens Cathedral with coloured light showing the original appearance

- High Gothic. The highly-individualized faces on facade of Amiens Cathedral

Towers and bells

Towers were an important feature of a Gothic Cathedral; they symbolised the aspiration toward heaven.[24] The traditional Gothic arrangement, following the Basilica of Saint Denis near Paris, was two towers of equal size on the west facade, flanking a porch with three portals. In Normandy and England, a central tower was often added over the meeting point of the transept and the main body of the church, as at Salisbury Cathedral.[24]

Since the towers were usually built last, sometimes long after other parts of the building, they were often built entirely or partly in different styles. The south tower of Chartres Cathedral is in large part still the originally romanesque tower, bullt in the 1140s. The north tower, built at the same time, was struck by lightning and was rebuilt in the 16th century in the Flamboyantstyle.[24]

Towers had had the practical purpose of serving as watch towers, and, more important, housing bells which chimed the hour, and rang to celebrate important events, when the King was in attendance, or for funerals and periods of mourning.Notre Dame de Paris was originally equipped with ten bells, eight in the north tower and two, the largest, in the south tower.[25] The principal bell, or bourdon, called Emmanuel, was installed in the north tower in the 15th century, and is still in place. It required the strength of eleven men, pulling on ropes from a chamber below, to ring that single bell. The ringing from the bells was so loud that the bell-ringers were deafened for several hours afterwards.[25]

Medieval illustration of building the Tower of Babel (Germany, c.1370)

Medieval illustration of building the Tower of Babel (Germany, c.1370) "Tower of Babel under construction", showing medieval cranes, German National Museum (1590s)

"Tower of Babel under construction", showing medieval cranes, German National Museum (1590s) Chartres Cathedral: The Flamboyant Gothic North Tower (finished 1513) (left) and Romanesque South Tower (1144–1150) (right)

Chartres Cathedral: The Flamboyant Gothic North Tower (finished 1513) (left) and Romanesque South Tower (1144–1150) (right).jpg) The Bourdon Emmanuel (15th century), the oldest surviving bell of Notre Dame de Paris

The Bourdon Emmanuel (15th century), the oldest surviving bell of Notre Dame de Paris

Notes and Citations

- Wenzler 2018, p. 47.

- Wenzler 2018, p. 48.

- McNamara 2017, p. 228.

- Mignon 2015, p. 31.

- Harvey 1974, p. 149.

- Wenzler 2018, p. 51.

- Bechmann 2017, p. 252.

- Wenzler 2018, p. 62.

- Watkin 1986, p. 143-144.

- Bechmann 2017, p. 261.

- Bechmann 2016, p. 252-254.

- Wenzler 2018, p. 65.

- Wenzler 2018, p. 67.

- Bechmann 2017, p. 254-257.

- Bechmann 2017, p. 257.

- Mignon 2015, p. 45.

- Bechmann 2017, p. 206.

- Bechmann 2017, p. 252-253.

- Houvet 2019, p. 17–.

- stained glass at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Wenzel 2018, p. 15.

- Wenzler 2018, p. 79.

- Chastel 2000, p. 130.

- McNamara 2017.

- Tritagnac & Coloni 1984, pp. 249-255.

Bibliography

- Bechmann, Roland (2017). Les Racines des Cathédrales (in French). Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-90651-7.

- Harvey, John (1974). Châteaux et Cathédrals-L'Art des Batisseurs, L'Encyclopedie de la Civilisation (in French). London: Thames and Hudson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Houvet, E (2019). Miller, Malcolm B. (ed.). Chartres - Guide of the Cathedral. Éditions Houvet. ISBN 2-909575-65-9.

- McNamara, Denis (2017). Comprendre l'Art des Églises (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-589952-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tritagnac, André; Coloni, Marie-Jeanne (1984). Decouvrir Notre-Dame de Paris. Paris: Les Éditions de Cerf. ISBN 2-204-02087-7.

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0-7126-1279-3.

- Wenzler, Claude (2018). Cathédales Gothiques - un Défi Médiéval (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-7712-9.