Winchester Cathedral

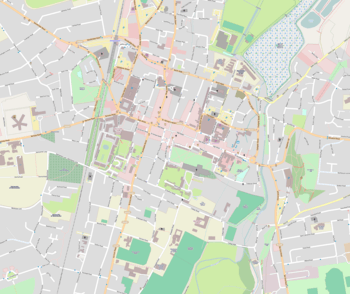

Winchester Cathedral is a cathedral of the Church of England in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It is one of the largest cathedrals in Europe, with the greatest overall length of any Gothic cathedral.[2]

| Winchester Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity | |

View of the long nave, central tower, north transept and west front | |

Winchester Cathedral | |

| Location | Winchester, Hampshire |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Website | Official website |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 24 March 1950[1] |

| Style | Norman, Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1079 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 558 ft 1 in (170.1 m) |

| Nave height | 78 feet (24 m) |

| Tower height | 150 feet (46 m) |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Winchester (since c.650) |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Tim Dakin |

| Dean | Catherine Ogle |

| Precentor | Andrew Trenier (Canon Sacrist) |

| Chancellor | Roland Riem (Vice-Dean & Pastor) |

| Canon(s) | Mark Collinson (Principal, School of Mission) |

| Canon Treasurer | Annabelle Boyes (lay; Receiver General & COO) |

Dedicated to the Holy Trinity,[3] Saint Peter, Saint Paul and, before the Reformation, Saint Swithun,[4] it is the seat of the Bishop of Winchester and centre of the Diocese of Winchester. The cathedral is a Grade I listed building.[3]

Pre-Norman cathedral

The cathedral was founded in 642 on a site immediately to the north of the present one. This building became known as the Old Minster. It became part of a monastic settlement in 971.

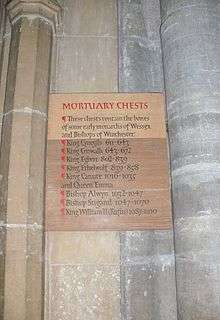

Saint Swithun was buried near the Old Minster and then in it, before being moved to the new Norman cathedral. So-called[5] mortuary chests said to contain the remains of Saxon kings such as King Eadwig of England and his wife Ælfgifu, first buried in the Old Minster, are in the present cathedral. The Old Minster was demolished in 1093, immediately after the consecration of its successor.[6]

Architectural history of new cathedral

Norman

In 1079, Walkelin, Bishop of Winchester, began work on a completely new cathedral.[6] Much of the limestone used to build the structure was brought across from quarries around Binstead, Isle of Wight. Nearby Quarr Abbey draws its name from these workings, as do several nearby places such as Stonelands and Stonepitts. The remains of the Roman trackway used to transport the blocks are still evident across the fairways of the Ryde Golf Club, where the stone was hauled from the quarries to the hythe at the mouth of Binstead Creek, and thence by barge across the Solent and up to Winchester.

The building was consecrated in 1093. On 8 April of that year, according to the Annals of Winchester, "in the presence of almost all the bishops and abbots of England, the monks came with the highest exultation and glory from the old minster to the new one: on the Feast of S. Swithun they went in procession from the new minster to the old one and brought thence S. Swithun's shrine and placed it with honour in the new buildings, and on the following day Walkelin's men first began to pull down the old minster."[6]

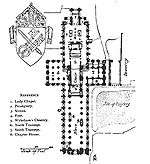

A substantial amount of the fabric of Walkelin's building, including crypt, transepts and the basic structure of the nave, survives.[7] The original crossing tower, however, collapsed in 1107, an accident blamed by the cathedral's medieval chroniclers on the burial of the dissolute William Rufus beneath it in 1100.[6] Its replacement, which survives today, is still in the Norman style, with round-headed windows. It is a squat, square structure, 50 feet (15 m) wide, but rising only 35 feet (11 m) above the ridge of the transept roof.[8] The Tower is 150 feet (46 m) tall.[9]

Gothic

After the consecration of Godfrey de Luci as bishop in 1189, a retrochoir was added in the Early English style. The next major phase of rebuilding was not until the mid-14th century, under bishops Edington and Wykeham.[10] Edingdon (1346–1366)[11] removed the two westernmost bays of the nave, built a new west front and began the remodelling of the nave.[12]

Under William of Wykeham (1367–1404) the Romanesque nave was transformed, recased in Caen stone and remodelled in the Perpendicular style,[13] with its internal elevation divided into two, rather than the previous three, storeys.[14] The wooden ceilings were replaced with stone vaults.[13]

Wykeham's successor, Henry of Beaufort (1405–1447) carried out fewer alterations, adding only a chantry on the south side of the retrochoir, although work on the nave may have continued through his episcopy.[15] His successor, William of Waynflete (1447–1486), built another chantry in a corresponding position on the north side. Under Peter Courtenay (Bishop 1486–1492) and Thomas Langton (1493–1500), there was more work. De Luci's Lady chapel was lengthened, and the Norman side aisles of the presbytery replaced. In 1525, Richard Foxe (Bishop 1500–1528) added the side screens of the presbytery, which he also gave a wooden vault.[10] With its progressive extensions, the east end is now about 110 feet (34 m) beyond that of Walkelin's building.[16]

Dissolution of the monasteries

King Henry VIII seized control of the Catholic Church in England and declared himself head of the new Church of England. The Benedictine foundation, the Priory of Saint Swithun, was dissolved. The priory surrendered to the king in 1539. The next year a new chapter was formed, and the last prior, William Basyng, was appointed dean.[17] The monastic buildings, including the cloister and chapter house, were later demolished, mostly during the 1560–1580 tenure of the reformist bishop Robert Horne.[18][19]

Choir screen

The Norman choir screen, having fallen into a state of decay, was replaced in 1637–40 by a new one designed by Inigo Jones. It was in a classical style, with bronze figures by Hubert le Sueur of James I and Charles I in niches. It was removed in 1820s, by when its style was felt inappropriate in an otherwise medieval building. The central bay, with its archway, is now in the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at Cambridge;[20] it was replaced by a Gothic screen by William Garbett, then the surveyor to the Dean and Chapter of the Cathedral, along with other repairs conducted by him, its design based on the west doorway of the nave.[21]

This stone structure was removed in the 1870s to make way for a wooden one designed by George Gilbert Scott,[22] who modelled it on the canopies of the choir stalls of the monks (dating from around 1308).[23] Scott's west-facing screen has been much criticised, although the carving is of superlative workmanship and virtually replicates the earlier, albeit finer, carving of the early 14th-century east-facing return stalls on to which it backs. The displaced bronze statues of the Stuart kings were moved to the west end of the Cathedral, standing in niches on each side of the central door. Scott's work was otherwise conservative. He moved the lectern to the north side of the quire beside the pulpit, facing west, where it remained for a century before returning to its present central position, now facing east.

Twentieth century

Restoration work was carried out by T. G. Jackson in 1905–12. Waterlogged foundations on the south and east walls were reinforced by diver William Walker, packing the foundations with more than 25,000 bags of concrete, 115,000 concrete blocks, and 900,000 bricks. Walker worked six hours a day from 1906 to 1912 in total darkness at depths up to 20 feet (6 m), and is credited with saving the cathedral from total collapse.[24] For this he was awarded the MVO.[25]

In 1931 the new Dean, E. Gordon Selwyn founded the Friends of Winchester Cathedral. A key element of the Friends’ policy was to “undertake schemes of repair which the Dean and Chapter consider necessary.” Dean Selwyn identified the need to install electric light and improve the Cathedral’s heating and sound system. The total estimated cost of heating and lighting was £10,000 and the works programme ran until 1938. A local firm Dicks & Sons, was appointed to undertake the work. It was headed by Miss Jeanie Dicks, the first female member of the Electrical Contractors Association.[26] It was discovered that replacing the gas lights in choir-stall with electrical ones involved running cables through the crypt. Some coffins had to be removed and were reverently reburied. Jane Austen’s coffin was moved gently to one side.[27]

During the same years, Dean Selwyn commissioned embroiderer Louisa Pesel to produce and deliver new fabric furnishings for the Cathedral. She worked with Sybil Blunt to train women in the skills required, made the designs and supervised the programme which was completed by 1936. The Friends funded the project, which created 360 kneelers, 96 alms bags, 36 long cushions, 1 lectern carpet, 1 litany desk kneeler, 3 seat cushions and 1 book cushion for the Bishop’s throne, 6 long seats for lay clerks, 2 bench cushions for choristers, 18 yards border for five communion rail kneelers and 25 borders for chapter kneelers. These tapestries depicted the history of Winchester Cathedral until 1936.[27]

In July 1934 a "Festival of Music and Drama" was held, supported by the new Friends organisation, with the aim of “helping the effort which the Dean and Chapter are making to raise £6,000 this year for the purpose of lighting and heating the Cathedral.” The festival included a play, The Marriage of Henry IV, written for the occasion, musical programmes, an exhibition the work of the Broderers and viewings of the Cathedral Library treasures. Dean Selwyn’s book, The Story of Winchester Cathedral, was published in the same year.[27]

Funerals, coronations, and marriages

Important events which took place at Winchester Cathedral include:

- Funeral of King Harthacanute (1042)

- Funeral of King William II of England (1100)

- Coronation of Henry the Young King and his queen, Marguerite (1172)

- Second coronation of Richard I of England (1194)

- Marriage of King Henry IV of England and Joanna of Navarre (1403)

- Marriage of Queen Mary I of England and King Philip II of Spain (1554)

Memorials and artworks

In the south transept there is a "Fishermen's Chapel", which is the burial place of Izaak Walton. Walton, who died in 1683, was the author of The Compleat Angler and a friend of John Donne. In the nave sanctuary is the bell from HMS Iron Duke, which was the flagship of Admiral John Jellicoe at the Battle of Jutland in 1916.[28]

A statue of Joan of Arc was erected when she was canonised as a saint by the Pope in 1923. The statue faces the Chancery Chapel of Cardinal Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester, who presided at her death by burning at the stake in Rouen in 1431.

The crypt, which frequently floods, houses a statue by Antony Gormley, called Sound II, installed in 1986, and a modern shrine to Saint Swithun. The mysterious statue contemplates the water held in cupped hands. Gormley spoke of the connection of memories to basic elements of the physical world: "Is it possible to do this and make something fresh, like dew or frost – something that just is, as if its form had always been like this?" There is also a statue in the retrochoir of William Walker, the deep-sea diver who worked under water in the crypt between 1906 and 1911 underpinning the nave and shoring up the walls, along with a bust of him in the cathedral grounds near the refectory.[25]

A series of nine icons were installed between 1992 and 1996 in the retrochoir screen, which for a short time protected the relics of St Swithun destroyed by Henry VIII in 1538. These icons, influenced by the Russian Orthodox tradition, were created by Sergei Fyodorov and dedicated in 1997. They include the local religious figures St Swithun and St Birinus. Beneath the retrochoir icons is the Holy Hole once used by pilgrims to crawl beneath and lie close to the healing shrine of St Swithun.

The sculptor Alan Durst was responsible for the carving on one of the memorials in the church.

Stained glass

The cathedral's huge medieval stained glass West Window was deliberately smashed by Cromwell's forces after the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642.[29][30] After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the broken glass was gathered up and assembled randomly, in a manner something like pique assiette mosaic work. There was little attempt to reconstruct the original pictures, although some small sections do have less abstract images. Some surviving fragments are on display at the Abbey Museum of Art and Archaeology in Australia,[31] including examples of the signature blue colour found only in Winchester stained glass.

The Epiphany Chapel has a series of Pre-Raphaelite stained glass windows designed by Edward Burne-Jones and made in William Morris's workshop. The foliage decoration above and below each pictorial panel is unmistakably by William Morris, and at least one of the figures bears a striking resemblance to Morris's wife Jane, who frequently posed for Dante Gabriel Rossetti and other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Knowles' cross

The Guardian Angels' Chapel had a new cross dedicated during a service of sung Eucharist at 11:00 am on 13 July 2001. The cross, by Justin Knowles, sits in a sandstone niche. The cross was made from cerulean blue glass (cerulean meaning "sky-blue") by the Czech glass artist Jan Frydrych. It sits on a plinth of black granite, with white flecks. Geometrically, it has four equal parts: a base, an upright, a cross piece, and a top. The top is somewhat like the cross of St Peter, while the stem is reminiscent of a Latin cross. The arrangement creates an optical illusion that the verticals are considerably longer. The blue reflects the vault portals of the chapel.

Bells

The cathedral possesses the only diatonic ring of fourteen church bells in the world, with a tenor (heaviest bell) weighing 36 long hundredweight (4,000 lb; 1,800 kg).[32] The back twelve were all cast by John Taylor & Co in 1937. They were augmented to fourteen when two new trebles and a 4♯ (sharp 4th) were added in 1992 by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry.[33] Also there is an 8♭ (flat 8th) which was cast by Anthony Bond in 1621.

Cultural connections

Nowadays the cathedral draws many tourists as a result of its association with Jane Austen, who died in Winchester on 18 July 1817. Her funeral was held in the cathedral, and she was buried in the north aisle. The inscription on her tombstone makes no mention of her novels, but a later brass tablet, paid for from the proceeds of her first biography, describes her as "known to many by her writings".[34] There is also a memorial window in her honour by C E Kempe.[35]

Having spent three years in the city as a child, the novelist Anthony Trollope borrowed features of the cathedral and the city for his Chronicles of Barsetshire.[36] In 2005, the building was used as a film set for The Da Vinci Code, with the north transept used as the Vatican. Following this, the cathedral hosted discussions and displays to debunk the book.[37]

Winchester Cathedral is possibly the only cathedral to have had popular songs written about it. "Winchester Cathedral" was a UK top ten hit and a US number one song for The New Vaudeville Band in 1966. The cathedral was also the subject of the Crosby, Stills & Nash song "Cathedral" from their 1977 album CSN. Liverpool-based band Clinic released an album titled Winchester Cathedral in 2004.[38]

In 1992, the British rosarian David Austin introduced a white sport of his rose cultivar "Mary Rose" (1983) as "Winchester Cathedral".

When he was posted to England during the First World War, Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, visited the Cathedral and had an initial experience of the presence of God.

The Cathedral is the starting point of the 34-mile-long St Swithun's Way a Long-distance footpath which was opened in 2002 to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II.

Public access

In common with many other Anglican cathedrals in the United Kingdom, an admission fee has been charged for visitors to enter the cathedral since March 2006. Visitors may request an annual pass for the same price as a single admission.[39]

Dean and chapter

As of 8 February 2019:[40]

- Dean—Catherine Ogle (since 11 February 2017 installation)

- Vice-Dean, Canon Chancellor and Pastor—Roland Riem (Vice-Dean since 2012; Canon Pastor since end of June 2005;[41] Chancellor since before 2011)[42]

- Canon Precentor and Sacrist—vacant since December 2018[43]

- Canon Principal (Diocesan Canon) & Principal, School of Mission—Mark Collinson (since 2015)[44]

- Receiver General and Canon Treasurer (Chief Operating Officer)—Annabelle Boyes (lay; since 2008)

Disposal of the dead

Burials

- Saint Birinus—his relics were eventually translated here

- Walkelin, first Norman Bishop of Winchester (1070–1098)

- Henry of Blois (or Henry of Winchester), Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey (1126–1129) and Bishop of Winchester (1129–1171)

- Richard of Ilchester, Bishop of Winchester (1173–1188) and medieval English statesman

- Godfrey de Luci, Bishop of Winchester (1189–1204)

- Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester (1205–1238) and Chief Justiciar of England (1213–c.1215)

- Henry Beaufort (1375–1447), Cardinal and Bishop of Winchester (legitimised son of John of Gaunt and Lord Chancellor of England under Henry V and Henry VI)

- Izaak Walton, author of The Compleat Angler (9 August 1593 – 15 December 1683)

- John Ecton, Queen Anne's Bounty official, legal compiler and author, died at Turnham Green, Middlesex, on 20 August 1730[45]—his will, bearing date 7 July 1730, was proved at London, 8 September 1730, by his widow, Dorothea Ecton, noting that he desired to be buried in Winchester Cathedral[46]

- Jane Austen (1817)[47]

Displaced in mortuary chests

- Cynegils, King of Wessex (611–643)

- Cenwalh, King of Wessex (643–672)

- Egbert of Wessex, King of Wessex (802–839)

- Ethelwulf, King of Wessex (839–856)

- Eadred, King of England (946–955)

- Eadwig, King of England and later Wessex (955–959)

- Cnut or Canute, King of England (1016–1035) and also of Denmark and Norway

- Emma of Normandy, wife of Cnut and also Ethelred II of England

- William II 'Rufus', King of England (1087–1100)—not in the traditional tomb associated with him, which may in fact be that of Henry of Blois, brother of King Stephen of England

Also

- Harthacnut, King of England (1040–1042) and also of Denmark

- Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury (d. 1072)

One of the mortuary chests also refers to a king 'Edmund', of which nothing else is known. It is possible that this could be Edmund Ironside, King of England (1016) but he is buried at Glastonbury Abbey by most accounts, including the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[48]

Originally buried at Winchester

- Edward the Elder, King of England (899–924)—later moved to Hyde Abbey

- Alfred the Great, King of Wessex (875–899)—moved from Old Minster and later to Hyde Abbey

Organ

The earliest recorded organ at Winchester Cathedral was in the 10th century; it had 400 pipes and could be heard throughout the city.[49] The earliest known organist of Winchester Cathedral is John Dyer in 1402.

The current organ, the work of master organ builder Henry Willis, was first displayed in the Great Exhibition of 1851, where it was the largest pipe organ. Winchester Cathedral organist Samuel Sebastian Wesley recommended its purchase to the dean and chapter; it was reduced in size and installed in 1854. It was modified in 1897 and 1905, and completely rebuilt by Harrison & Harrison in 1937 and again in 1986–88. Organists at Winchester have included Christopher Gibbons whose patronage aided the revival of church music after the Interregnum, Samuel Sebastian Wesley, the composer of sacred music,[50] and Martin Neary, who arranged the music for the funeral of Diana, Princess of Wales at Westminster Abbey.

See also

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- English Gothic architecture

- Priory of Saint Swithun

- Romanesque architecture

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- List of Gothic Cathedrals in Europe

Notes

- "Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity". British Listed Buildings. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- Alec Clifton-Taylor, The Cathedrals of England (Thames & Hudson, 1969)

- Historic England. "CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF THE HOLY TRINITY (1095509)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- John Crook, ed. Winchester Cathedral: Nine Hundred Years, 1093-1993 (Guildford, U.K.: 1993) pp. 57-59

- ""The Winchester Mortuary Chests", from EnglishMonarchs.co.uk". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- Sergeant 1899, p.7

- Sergeant 1899, p.16

- Sergeant 1899, p.27

- "Project Gutenburg". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- Sergeant 1899, p.10

- Dates of bishops from Sergeant 1899, pp.107–17

- Bumpus 1930, p.40

- Sergeant 1899, p.9

- Sergeant 1899, p.35

- Sergeant 1899, p.38

- Sergeant 1899, p.28

- Stevens, John (1722). The History of the Antient Abbeys Monasteries, Cathedrals and Collegiate Churches. London. p. 222.

- Sergeant 1899, pp.13,

- Bumpus 1930, p.45

- Harris, John; Higgott, Gordon (1989). Inigo Jones:Complete Architectural Drawings. Royal Academy of Arts. pp. 248–50.

- "Photograph of the gothic stone choir screen in Winchester Cathedral". Winchester Museums. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Photograph of the carved wooden choir screen in Winchester Cathedral". Winchester Museums. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- Sergeant 1899, p.50

- "Hampshire – History – Saving the Cathedral". BBC. 22 September 2008. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- Bussby, Frederick (1970). William Walker: The Diver who Saved Winchester Cathedral. Friends of Winchester Cathedral. pp. 16–18. ISBN 0903346087.

- Drew, Lesley (1999). "The Lady of the Lights". Winchester Cathedral Record. 68.

- Bradley, Lindy. ""E. GORDON SELWYN, DD, Dean of Winchester 1931-1958 FOUNDER OF THE FRIENDS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2016.

- "Battle of Jutland Order of Battle". Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- "Collaged glass in Winchester Cathedral". Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- BBC: Cathedrals of Britain Archived 5 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Winchester Cathedral". Winchester and Portsmouth Guild of Church Bell Ringers.

- "Cathedral Bells". Winchester Cathedral. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- "Winchester – Jane Austen's final resting place". Hampshire County Council. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- Crook, John (2002). Winchester Cathedral. Andover: Pitkin. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-85372-875-5.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "WINCHESTER, UK: Bishop accused of cashing in on the 'Da Vinci heresy' | VirtueOnline – The Voice for Global Orthodox Anglicanism". www.virtueonline.org. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- "Winchester Cathedral – Clinic (2004) album review". allmusic.com. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- "Winchester Cathedral, rationale for charging" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- Winchester Cathedral — Who Does What Archived 9 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed 8 February 20189)

- Winchester Cathedral — Annual Report 2005(Archived from the original, 8 November 2005; archive accessed 8 January 2018)

- Winchester Cathedral — Annual Report 2011 Archived 9 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine (Accessed 8 January 2018)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Diocese of Winchester — School of Mission team (Accessed 8 January 2018)

- Hist. Reg. vol. xv., Chron. Diary, p. 55

- registered in P. C. C. 255 Auber

- Park Honan (1987). Jane Austen: Her Life. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 407. ISBN 0-312-01451-1.

- For further information, see http://www.churchmonumentssociety.org/Mortuary_Chests.html Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- The cathedral organ Archived 14 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine; Winchester Cathedral; accessed 2012-04-07

- Scholes, Percy (1970) The Oxford Companion to Music; 10th edition. Oxford University Press; p. 1115

Bibliography

- Bumpus, T Francis (1930). The Cathedrals of England and Wales. London: T. Werner Laurie. OCLC 5626538.

- Sergeant, Philip Walsingham (1899). The Cathedral Church of Winchester. Bell's Cathedrals. London: George Bell and Sons. OCLC 537801.

Further reading

- Willis, Robert (1846; 1980) The Architectural History of Winchester Cathedral; by R. Willis [with] The Normans as Cathedral Builders; by Christopher N. L. Brooke. Winchester: Friends of Winchester Cathedral (First work is facsimile reprint of article from Proceedings at the Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1845, published 1846.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Winchester Cathedral. |