First Battle of Picardy

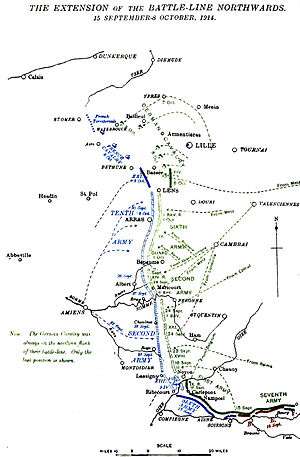

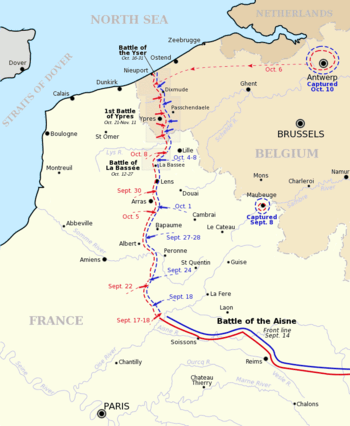

The First Battle of Picardy (22–26 September 1914) took place during the Race to the Sea (17 September – 19 October) and the First Battle of the Aisne (13 September – 28 September). The "race" was a Franco-British counter-offensive, which followed the Battle of the Frontiers (7 August–13 September) and the German advance into France during the Great Retreat, which ended at the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September).[lower-alpha 1] The term describes reciprocal attempts by the Franco-British and German armies to envelop the northern flank of the opposing army, through Picardy, Artois and Flanders.

The first outflanking attempt resulted in an encounter battle in Picardy. The French Sixth Army attacked up the Oise river valley towards Noyon, as the Second Army assembled further north, ready to attempt to advance round the northern flank of the German 1st Army. Both French armies managed to advance successively on a line from Roye to Chaulnes, until the German 6th Army and other reinforcements arrived from Lorraine and halted the French advance. Both sides then attempted another flanking move to the north, which merged into the Battle of Albert (25–29 September).[lower-alpha 2]

Background

Strategic developments

General Erich von Falkenhayn replaced Colonel-General Helmuth von Moltke the Younger as Chief of the German General Staff on 14 September, when the German front in France was being consolidated in Lorraine and on the Aisne. The open western flank beyond the 1st Army and the danger of attacks from the National redoubt of Belgium, where the Siege of Antwerp had begun on 20 August, created a dilemma in which the German positions had to be maintained, when only offensive operations could lead to decisive victory. Appeals for the reinforcement of the Eastern Front could not be ignored and Falkenhayn cancelled a plan for the 6th Army to break through near Verdun and ordered that it move across France to the right wing of the German armies. The flank of 1st Army was at Compiègne, beyond which there were no German forces until Antwerp. Falkenhayn could reinforce the 1st Army with the 6th Army, send it to Antwerp or divide the army by reinforcing the 1st Army and the Antwerp siege with part of the army, while the rest operated in the area between.[9]

Falkenhayn chose to move the 6th Army to Maubeuge and outflank the Franco-British left wing, withdrawing the 1st, 7th Army and 2nd Army to La Fère, Laon and Reims while the 6th Army was redeploying. The 3rd Army, 4th Army and 5th Army were to defend if the French attacked and attack to the south-west beginning on 18 September. General Karl von Bülow and Colonel Gerhard Tappen of the Operations Branch of the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, Supreme Army Command) objected, because the time needed to move the 6th Army, would concede the initiative to the French and recommended an attack by the 1st and 7th armies, with reinforcements from the armies to the east for an offensive from Reims, Fismes and Soissons, since the French could redeploy troops on undamaged railways and the risk of separating the 1st and 2nd armies again would be avoided. Falkenhayn cancelled the retirement and ordered the 6th Army to assemble at St. Quentin. An attack south of Verdun to capture forts on the Meuse and encircle Verdun from the south and an attack from Soissons to Reims would prevent the French from moving troops to the flanks.[10]

Tactical developments

First Battle of the Aisne

_13_September_(black_line).jpg)

On 10 September, Joffre ordered the French armies and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to advance and exploit the victory of the Marne. For four days, the armies on the left flank advanced and gathered up German stragglers, wounded and equipment, opposed only by rearguards. From 11 and 12 September, Joffre ordered outflanking manoeuvres by the armies on the left flank but their advance was too slow to catch the Germans. The Germans ended the retirement on 14 September, on high ground on the north bank of the Aisne and began to dig in, which reduced the French advance from 15–16 September to a few local gains. French troops had begun to move westwards from Lorraine on 2 September, using the undamaged railways behind the French front, which were able to move a corps to the left flank in 5–6 days. On 17 September, the French Sixth Army attacked from Soissons to Noyon, at the westernmost point of the French flank, with the XIII and IV Corps, supported by two divisions of the 6th Group of Reserve Divisions, after which the fighting moved north to Lassigny and the French dug in around Nampcel.[11]

The German armies attacked from Verdun westwards to Reims and the Aisne on 20 September, cut the main railway from Verdun to Paris and created the St Mihiel salient at the Battle of Flirey (19 September – 11 October), south of the Verdun fortress zone. The main German effort remained on the western flank, which was revealed to the French by intercepted wireless messages.[12] By 28 September, the Aisne front had stabilised and the BEF began to withdraw on the night of 1/2 October, with the first troops arriving in the Abbeville area on the night of 8/9 October. The BEF prepared to commence operations in Flanders and join with the British forces which had been operating in Belgium since August.[13]

Prelude

Northward redeployments

The German IX Reserve Corps had arrived from Belgium by 15 September and the 6th Army was expected to complete a move from Lorraine from 13–23 September. Next day the corps joined the right flank of the 1st Army, for an attack to the south-west with the IV Corps, IX Reserve Corps and the 4th and 7th cavalry divisions. The 2nd Army commander Bülow, ordered Kluck the 1st Army commander, to cancel the offensive and withdraw the two corps behind the right flank of the 1st Army. On 16 September, the 2nd and 9th cavalry divisions were dispatched from the Aisne front as reinforcements but before the retirement began, the French XIII and IV corps on the left flank of Sixth Army, with the 61st and 62nd divisions of the 6th Group of Reserve Divisions, began to advance along the Oise and met the right flank of the German 1st Army between Carlepont and Noyon, on 17 September. On the right flank, the French 17th and 45th divisions attacked near Soissons and gained a foothold on the plateau of Cuffies, just north of the city.[11]

On 18 September, the French advance was stopped on a south-east to north-west line at Carlepont on the south bank of the Oise and Noyon on the north bank, which ended the first French outflanking move.[12] Joffre dissolved the Second Army in Lorraine and sent General Noël de Castelnau and the Second Army headquarters to the north of the Sixth Army, to take over the IV and XIII Corps, along with the 1st, 5th, 8th and 10th Cavalry divisions of the French II Cavalry Corps (General Louis Conneau) from the Sixth Army. The XIV Corps was transferred from the First Army and XX Corps from the original Second Army, to assemble south of Amiens, screened by the 81st, 82nd, 84th and 88th Territorial divisions, to protect French communications. The new French Second Army prepared to begin an advance on 22 September, on a line from Lassigny north to Roye and Chaulnes around the German flank.[14]

On 21 September, Falkenhayn met Bülow and agreed that the 6th Army should concentrate close to Amiens and attack towards the Channel coast and then envelop the French south of the Somme in a Schlachtentscheidung (decisive battle).[15] The XXI Corps, which had moved from Lunéville on 15 September and the I Bavarian Corps, which marched from Namur, arrived during 24 September but were diverted against the French Second Army as soon as they arrived, to extend the front northwards from Chaulnes to Péronne on 24 September, to attack the French bridgehead and drive the French back over the Somme.[16]

Battle

22–26 September

The French Second Army crossed the Avre on a line from Lassigny northwards to Roye and Chaulnes but met the German II Corps from the 1st Army, which had arrived from the Aisne front, where new entrenchments had enabled fewer men to garrison the front line. The corps moved into line on the night of 18/19 September, on the right flank of the IX Reserve Corps. Despite the assistance of four divisions of the II Cavalry Corps (Lieutenant-General Georg von der Marwitz), the Germans were pushed back to a line from Ribécourt to Lassigny and Roye, which menaced German communications through Ham and St. Quentin. On 21 September, the German XVIII Corps had begun a 50 miles (80 km) forced march from Reims and reached Ham on the evening of 23 September. On 24 September, the XVIII Corps attacked towards Roye and with the II Corps, forced back the French IV Corps. To the north, the French Second Army reached Péronne and formed a bridgehead on the east bank of the Somme, which exhausted the offensive capacity of the army.[17]

Joffre sent the XI Corps, which was the last French reserve, to the Second Army and began to withdraw three more corps as reinforcements.[18] The German XXI and I Bavarian corps recaptured Péronne and forced the Second Army west of the Somme, where the French managed to dig in on good defensive ground, from Lassigny to Roye and Bray. The German II Cavalry Corps moved north to make room for the II Bavarian Corps on the north bank of the Somme, which had marched from Valenciennes. On 25 September, a German attack near Noyon pushed back the Second Army. French reinforcements attacked again and from 25–27 September, a general action took place along the Western Front, from the Vosges to Péronne, after which the main effort of both sides took place further north, at the Battle of Albert (25–29 September). The German offensive took very little ground and after a lull the Germans renewed the offensive against the Second Army, which was driven back from Lassigny to a line from Ribecourt on the Oise, to Roye west of Chaulnes and the plateau north of the Somme, between Combles and Albert. On 1 October, the Germans attacked at Roye in the centre of the Second Army front and on 5 October, another attack at Lassigny was repulsed; on 7 October a French counter-attack between Chaulnes and Roye took 1,600 prisoners.[19]

Aftermath

Analysis

The French had used the undamaged railways behind their front to move troops more quickly than the Germans, who had to take long detours, wait for repairs to damaged tracks and replace rolling stock. The French IV Corps moved from Lorraine on 2 September in 109 trains and assembled by 6 September.[18] The French had been able to move troops in up to 200 trains per day and use hundreds of motor-vehicles, which were co-ordinated by two staff officers, Commandant Gérard and Captain Doumenc. The French had been able to use Belgian and captured German rail wagons and the domestic telephone and telegraph systems.[20] The initiative held by the Germans in August was not recovered and all troop movements to the right flank were piecemeal. Until the end of the Siege of Maubeuge (24 August – 7 September), only the single track from Trier to Liège, Brussels, Valenciennes and Cambrai was available. The line had to be used to supply the German armies, while the 6th Army had to be carried in the opposite direction, limiting the army to forty trains a day, when it took four days to move a corps. Information on German troop movements from wireless interception enabled the French to forestall German moves but the Germans had to rely on reports from spies, which were frequently wrong. The French resorted to more cautious infantry tactics, using cover to reduce casualties and a centralised system of control, as the German army commanders followed contradictory plans. The French did not need quickly to obtain a decisive result and could concentrate on conserving the army.[21]

Subsequent operations

The German II Bavarian Corps and the XIV Reserve Corps pushed back a French Territorial division from Bapaume and advanced towards Bray and Albert.[17] From 25–27 September the French XXI Corps and X Corps north of the Somme, with support on the right flank by the 81st, 82nd, 84th and 88th Territorial divisions (General Joseph Brugère) and the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 10th Cavalry divisions of the II Cavalry Corps (General Louis Conneau), defended the approaches to Albert. On 28 September, the French were able to stop the German advance on a line from Maricourt to Fricourt and Thiépval. The German II Cavalry Corps was stopped in the vicinity of Arras by the French cavalry. On 29 September, Joffre combined X Corps, which was 20 miles (32 km) north of Amiens, the II Cavalry Corps south-east of Arras and the subdivision d'Armée (General Louis de Maud'huy), which had a Reserve Division in Arras and one in Lens, into a new Tenth Army.[22]

Notes

- Writers and historians have criticised the term Race to the Sea and used several date ranges for the period of mutual attempts to outflank the opposing armies on their northern flanks. In 1925, James Edmonds the British official historian, used dates of 15 September – 15 October and in 1926 17 September – 19 October.[1][2] In 1929, the fifth volume of Der Weltkrieg the German Official History, described the progress of German outflanking attempts, without labelling them.[3] In 2001, Hew Strachan used 15 September – 17 October.[4] In, 2003 Andrew Clayton gave dates from 17 September – 7 October.[5] In 2005, Robert Doughty used the period from 17 September – 17 October and Robert Foley from 17 September to a period from 10–21 October.[6][7] In 2010, Jack Sheldon placed the beginning of the "erroneously named" race, from the end of the Battle of the Marne, to the beginning of the Battle of the Yser.[8]

- German armies are rendered in numbers "7th Army" and French armies in words "Second Army".

Footnotes

- Edmonds 1925, pp. 27–100.

- Edmonds 1926, pp. 400–408.

- Reichsarchiv 1929, p. 14.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 266–273.

- Clayton 2003, p. 59.

- Doughty 2005, p. 98.

- Foley 2005, pp. 101–102.

- Sheldon 2010, p. x.

- Strachan 2001, p. 264.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 264–265.

- Edmonds 1926, p. 388.

- Edmonds 1926, pp. 400–401.

- Edmonds 1926, pp. 407–408.

- Doughty 2005, p. 99.

- Foley 2005, p. 101.

- Edmonds 1926, p. 402.

- Edmonds 1926, pp. 401–402.

- Doughty 2005, p. 100.

- The Times 1915, pp. 485–486.

- Clayton 2003, p. 62.

- Strachan 2001, pp. 265–266.

- Edmonds 1926, pp. 402–403.

References

Books

- Clayton, A. (2003). Paths of Glory: The French Army 1914–18. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35949-3.

- Der Herbst-Feldzug 1914: Im Westen bis zum Stellungskrieg, im Osten bis zum Rückzug [The Autumn Campaign 1914: In the West up to Position Warfare, in the East to the Retreat]. Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Militärischen Operationen zu Lande [The World War 1914–1918: Military Operations on Land]. I (Die Digitale Landesbibliothek Oberösterreich online ed.). Berlin: Mittler & Sohn. 2012 [1929]. OCLC 838299944. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I. 1st edition: 1922 (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- Foley, R. T. (2007) [2005]. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich Von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916. Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- Sheldon, J. (2010). The German Army at Ypres 1914 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-113-0.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

Encyclopaedias

- The Times History of the War. II. London: The Times. 1914–1922. OCLC 220271012. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

Further reading

- Arras, Lens–Douai and the Battles of Artois (English ed.). Clermont-Ferrand: Michelin & Cie. 1919. OCLC 154114243. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Foch, F. (1931). Mémoire pour servir à l'histoire de la guerre 1914–1918: avec 18 gravures hors-texte et 12 cartes [The Memoirs of Marshal Foch] (PDF) (in French). trans. T. Bentley Mott (Heinemann ed.). Paris: Plon. OCLC 86058356. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Raleigh, W. A. (1969) [1922]. The War in the Air: Being the Story of the Part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. I (Hamish Hamilton ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 785856329. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- Sheldon, J. (2010). The German Army at Ypres 1914 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-113-0.

- Skinner, H. T.; Stacke, H. Fitz M. (1922). Principal Events 1914–1918. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. London: HMSO. OCLC 17673086. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- Tyng, S. (2007) [1935]. The Campaign of the Marne 1914 (Westholme Publishing ed.). New York: Longmans. ISBN 978-1-59416-042-4.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press ed.). Connecticut: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Battle of Picardy. |