Constantine the Great

Constantine the Great (Latin: Flavius Valerius Constantinus; Ancient Greek: Κωνσταντῖνος, romanized: Kōnstantînos; 27 February c. 272 – 22 May 337), also known as Constantine I, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337. Born in Dacia Ripensis (now Serbia), he was the son of Flavius Constantius, an Illyrian army officer who became one of the four emperors of the Tetrarchy. His mother, Helena, was Greek and of low birth. Constantine served with distinction under emperors Diocletian and Galerius campaigning in the eastern provinces against barbarians and the Persians, before being recalled west in 305 to fight under his father in Britain. After his father's death in 306, Constantine was acclaimed as emperor by the army at Eboracum (York). He emerged victorious in the civil wars against emperors Maxentius and Licinius to become sole ruler of the Roman Empire by 324.

| Constantine the Great | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Colossal head of Constantine (4th century), Capitoline Museums, Rome and Athens | |||||

| Roman emperor | |||||

| Reign | 25 July 306 – 22 May 337 (alone from 19 September 324) | ||||

| Predecessor | Constantius I | ||||

| Successor |

| ||||

| Co-emperors or rivals |

| ||||

| Born | 27 February c. 272[1] Naissus, Moesia Superior, Roman Empire (Niš, Serbia) | ||||

| Died | 22 May 337 (aged 65) Nicomedia, Bithynia, Roman Empire (İzmit, Turkey) | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue Detail | |||||

| |||||

| Greek | Κωνσταντίνος Α΄ | ||||

| Dynasty | Constantinian | ||||

| Father | Constantius Chlorus | ||||

| Mother | Helena | ||||

| Religion |

| ||||

As emperor, Constantine enacted administrative, financial, social and military reforms to strengthen the empire. He restructured the government, separating civil and military authorities. To combat inflation he introduced the solidus, a new gold coin that became the standard for Byzantine and European currencies for more than a thousand years. The Roman army was reorganised to consist of mobile units (comitatenses), and garrison troops (limitanei) capable of countering internal threats and barbarian invasions. Constantine pursued successful campaigns against the tribes on the Roman frontiers—the Franks, the Alamanni, the Goths and the Sarmatians—even resettling territories abandoned by his predecessors during the Crisis of the Third Century.

Constantine was the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity.[notes 1] Although he lived much of his life as a pagan, and later as a catechumen, he joined the Christian religion on his deathbed, being baptised by Eusebius of Nicomedia. He played an influential role in the proclamation of the Edict of Milan in 313, which declared tolerance for Christianity in the Roman Empire. He convoked the First Council of Nicaea in 325, which produced the statement of Christian belief known as the Nicene Creed.[3] The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built on his orders at the purported site of Jesus' tomb in Jerusalem and became the holiest place in Christendom. The papal claim to temporal power in the High Middle Ages was based on the fabricated Donation of Constantine. He has historically been referred to as the "First Christian Emperor" and he did favour the Christian Church. While some modern scholars debate his beliefs and even his comprehension of Christianity,[notes 2] he is venerated as a saint in Eastern Christianity.

The age of Constantine marked a distinct epoch in the history of the Roman Empire.[6] He built a new imperial residence at Byzantium and renamed the city Constantinople (now Istanbul) after himself (the laudatory epithet of "New Rome" emerged in his time, and was never an official title). It subsequently became the capital of the Empire for more than a thousand years, the later Eastern Roman Empire being referred to as the Byzantine Empire by modern historians. His more immediate political legacy was that he replaced Diocletian's Tetrarchy with the de facto principle of dynastic succession, by leaving the empire to his sons and other members of the Constantinian dynasty. His reputation flourished during the lifetime of his children and for centuries after his reign. The medieval church held him up as a paragon of virtue, while secular rulers invoked him as a prototype, a point of reference and the symbol of imperial legitimacy and identity.[7] Beginning with the Renaissance, there were more critical appraisals of his reign, due to the rediscovery of anti-Constantinian sources. Trends in modern and recent scholarship have attempted to balance the extremes of previous scholarship.

Sources

Constantine was a ruler of major importance, and he has always been a controversial figure.[8] The fluctuations in his reputation reflect the nature of the ancient sources for his reign. These are abundant and detailed,[9] but they have been strongly influenced by the official propaganda of the period[10] and are often one-sided;[11] no contemporaneous histories or biographies dealing with his life and rule have survived.[12] The nearest replacement is Eusebius's Vita Constantini—a mixture of eulogy and hagiography[13] written between AD 335 and circa AD 339[14]—that extols Constantine's moral and religious virtues.[15] The Vita creates a contentiously positive image of Constantine,[16] and modern historians have frequently challenged its reliability.[17] The fullest secular life of Constantine is the anonymous Origo Constantini,[18] a work of uncertain date,[19] which focuses on military and political events to the neglect of cultural and religious matters.[20]

Lactantius' De Mortibus Persecutorum, a political Christian pamphlet on the reigns of Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, provides valuable but tendentious detail on Constantine's predecessors and early life.[21] The ecclesiastical histories of Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret describe the ecclesiastic disputes of Constantine's later reign.[22] Written during the reign of Theodosius II (AD 408–450), a century after Constantine's reign, these ecclesiastical historians obscure the events and theologies of the Constantinian period through misdirection, misrepresentation, and deliberate obscurity.[23] The contemporary writings of the orthodox Christian Athanasius, and the ecclesiastical history of the Arian Philostorgius also survive, though their biases are no less firm.[24]

The epitomes of Aurelius Victor (De Caesaribus), Eutropius (Breviarium), Festus (Breviarium), and the anonymous author of the Epitome de Caesaribus offer compressed secular political and military histories of the period. Although not Christian, the epitomes paint a favourable image of Constantine but omit reference to Constantine's religious policies.[25] The Panegyrici Latini, a collection of panegyrics from the late third and early fourth centuries, provide valuable information on the politics and ideology of the tetrarchic period and the early life of Constantine.[26] Contemporary architecture, such as the Arch of Constantine in Rome and palaces in Gamzigrad and Córdoba,[27] epigraphic remains, and the coinage of the era complement the literary sources.[28]

Early life

Flavius Valerius Constantinus, as he was originally named, was born in the city of Naissus, (today Niš, Serbia) part of the Dardania province of Moesia on 27 February,[29] probably c. AD 272.[30] His father was Flavius Constantius, an Illyrian,[31][32] and a native of Dardania province of Moesia (later Dacia Ripensis).[33] Constantine probably spent little time with his father[34] who was an officer in the Roman army, part of the Emperor Aurelian's imperial bodyguard. Being described as a tolerant and politically skilled man,[35] Constantius advanced through the ranks, earning the governorship of Dalmatia from Emperor Diocletian, another of Aurelian's companions from Illyricum, in 284 or 285.[33] Constantine's mother was Helena, a Greek woman of low social standing from Helenopolis of Bithynia.[36] It is uncertain whether she was legally married to Constantius or merely his concubine.[37] His main language was Latin, and during his public speeches he needed Greek translators.[38]

_-_Foto_G._Dall'Orto_28-5-2006.jpg)

.jpg)

In July AD 285, Diocletian declared Maximian, another colleague from Illyricum, his co-emperor. Each emperor would have his own court, his own military and administrative faculties, and each would rule with a separate praetorian prefect as chief lieutenant.[39] Maximian ruled in the West, from his capitals at Mediolanum (Milan, Italy) or Augusta Treverorum (Trier, Germany), while Diocletian ruled in the East, from Nicomedia (İzmit, Turkey). The division was merely pragmatic: the empire was called "indivisible" in official panegyric,[40] and both emperors could move freely throughout the empire.[41] In 288, Maximian appointed Constantius to serve as his praetorian prefect in Gaul. Constantius left Helena to marry Maximian's stepdaughter Theodora in 288 or 289.[42]

Diocletian divided the Empire again in AD 293, appointing two caesars (junior emperors) to rule over further subdivisions of East and West. Each would be subordinate to their respective augustus (senior emperor) but would act with supreme authority in his assigned lands. This system would later be called the Tetrarchy. Diocletian's first appointee for the office of caesar was Constantius; his second was Galerius, a native of Felix Romuliana. According to Lactantius, Galerius was a brutal, animalistic man. Although he shared the paganism of Rome's aristocracy, he seemed to them an alien figure, a semi-barbarian.[43] On 1 March, Constantius was promoted to the office of caesar, and dispatched to Gaul to fight the rebels Carausius and Allectus.[44] In spite of meritocratic overtones, the Tetrarchy retained vestiges of hereditary privilege,[45] and Constantine became the prime candidate for future appointment as caesar as soon as his father took the position. Constantine went to the court of Diocletian, where he lived as his father's heir presumptive.[46]

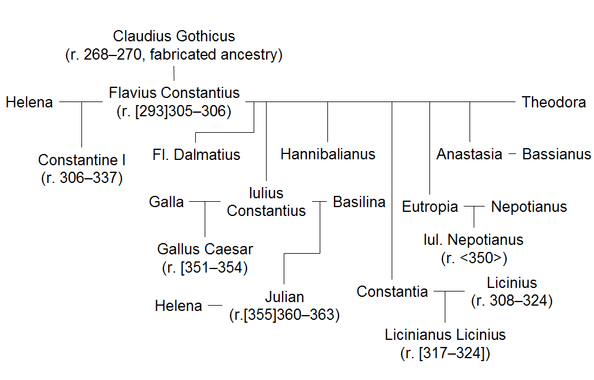

Constantine's parents and siblings, the dates in square brackets indicate the possession of minor titles

Constantine's parents and siblings, the dates in square brackets indicate the possession of minor titles

In the East

Constantine received a formal education at Diocletian's court, where he learned Latin literature, Greek, and philosophy.[47] The cultural environment in Nicomedia was open, fluid, and socially mobile; in it, Constantine could mix with intellectuals both pagan and Christian. He may have attended the lectures of Lactantius, a Christian scholar of Latin in the city.[48] Because Diocletian did not completely trust Constantius—none of the Tetrarchs fully trusted their colleagues—Constantine was held as something of a hostage, a tool to ensure Constantius' best behavior. Constantine was nonetheless a prominent member of the court: he fought for Diocletian and Galerius in Asia and served in a variety of tribunates; he campaigned against barbarians on the Danube in AD 296 and fought the Persians under Diocletian in Syria (AD 297), as well as under Galerius in Mesopotamia (AD 298–299).[49] By late AD 305, he had become a tribune of the first order, a tribunus ordinis primi.[50]

Constantine had returned to Nicomedia from the eastern front by the spring of AD 303, in time to witness the beginnings of Diocletian's "Great Persecution", the most severe persecution of Christians in Roman history.[51] In late 302, Diocletian and Galerius sent a messenger to the oracle of Apollo at Didyma with an inquiry about Christians.[52] Constantine could recall his presence at the palace when the messenger returned, when Diocletian accepted his court's demands for universal persecution.[53] On 23 February AD 303, Diocletian ordered the destruction of Nicomedia's new church, condemned its scriptures to the flames, and had its treasures seized. In the months that followed, churches and scriptures were destroyed, Christians were deprived of official ranks, and priests were imprisoned.[54]

It is unlikely that Constantine played any role in the persecution.[55] In his later writings, he would attempt to present himself as an opponent of Diocletian's "sanguinary edicts" against the "Worshippers of God",[56] but nothing indicates that he opposed it effectively at the time.[57] Although no contemporary Christian challenged Constantine for his inaction during the persecutions, it remained a political liability throughout his life.[58]

On 1 May AD 305, Diocletian, as a result of a debilitating sickness taken in the winter of AD 304–305, announced his resignation. In a parallel ceremony in Milan, Maximian did the same.[59] Lactantius states that Galerius manipulated the weakened Diocletian into resigning, and forced him to accept Galerius' allies in the imperial succession. According to Lactantius, the crowd listening to Diocletian's resignation speech believed, until the very last moment, that Diocletian would choose Constantine and Maxentius (Maximian's son) as his successors.[60] It was not to be: Constantius and Galerius were promoted to augusti, while Severus and Maximinus Daia, Galerius' nephew, were appointed their caesars respectively. Constantine and Maxentius were ignored.[61]

Some of the ancient sources detail plots that Galerius made on Constantine's life in the months following Diocletian's abdication. They assert that Galerius assigned Constantine to lead an advance unit in a cavalry charge through a swamp on the middle Danube, made him enter into single combat with a lion, and attempted to kill him in hunts and wars. Constantine always emerged victorious: the lion emerged from the contest in a poorer condition than Constantine; Constantine returned to Nicomedia from the Danube with a Sarmatian captive to drop at Galerius' feet.[62] It is uncertain how much these tales can be trusted.[63]

In the West

Constantine recognized the implicit danger in remaining at Galerius' court, where he was held as a virtual hostage. His career depended on being rescued by his father in the west. Constantius was quick to intervene.[64] In the late spring or early summer of AD 305, Constantius requested leave for his son to help him campaign in Britain. After a long evening of drinking, Galerius granted the request. Constantine's later propaganda describes how he fled the court in the night, before Galerius could change his mind. He rode from post-house to post-house at high speed, hamstringing every horse in his wake.[65] By the time Galerius awoke the following morning, Constantine had fled too far to be caught.[66] Constantine joined his father in Gaul, at Bononia (Boulogne) before the summer of AD 305.[67]

From Bononia, they crossed the Channel to Britain and made their way to Eboracum (York), capital of the province of Britannia Secunda and home to a large military base. Constantine was able to spend a year in northern Britain at his father's side, campaigning against the Picts beyond Hadrian's Wall in the summer and autumn.[68] Constantius' campaign, like that of Septimius Severus before it, probably advanced far into the north without achieving great success.[69] Constantius had become severely sick over the course of his reign, and died on 25 July 306 in Eboracum. Before dying, he declared his support for raising Constantine to the rank of full augustus. The Alamannic king Chrocus, a barbarian taken into service under Constantius, then proclaimed Constantine as augustus. The troops loyal to Constantius' memory followed him in acclamation. Gaul and Britain quickly accepted his rule;[70] Hispania, which had been in his father's domain for less than a year, rejected it.[71]

Constantine sent Galerius an official notice of Constantius' death and his own acclamation. Along with the notice, he included a portrait of himself in the robes of an augustus.[72] The portrait was wreathed in bay.[73] He requested recognition as heir to his father's throne, and passed off responsibility for his unlawful ascension on his army, claiming they had "forced it upon him".[74] Galerius was put into a fury by the message; he almost set the portrait and messenger on fire.[75] His advisers calmed him, and argued that outright denial of Constantine's claims would mean certain war.[76] Galerius was compelled to compromise: he granted Constantine the title "caesar" rather than "augustus" (the latter office went to Severus instead).[77] Wishing to make it clear that he alone gave Constantine legitimacy, Galerius personally sent Constantine the emperor's traditional purple robes.[78] Constantine accepted the decision,[77] knowing that it would remove doubts as to his legitimacy.[79]

Early rule

Constantine's share of the Empire consisted of Britain, Gaul, and Spain, and he commanded one of the largest Roman armies which was stationed along the important Rhine frontier.[80] He remained in Britain after his promotion to emperor, driving back the tribes of the Picts and securing his control in the northwestern dioceses. He completed the reconstruction of military bases begun under his father's rule, and he ordered the repair of the region's roadways.[81] He then left for Augusta Treverorum (Trier) in Gaul, the Tetrarchic capital of the northwestern Roman Empire.[82] The Franks learned of Constantine's acclamation and invaded Gaul across the lower Rhine over the winter of 306–307 AD.[83] He drove them back beyond the Rhine and captured Kings Ascaric and Merogais; the kings and their soldiers were fed to the beasts of Trier's amphitheatre in the adventus (arrival) celebrations which followed.[84]

Constantine began a major expansion of Trier. He strengthened the circuit wall around the city with military towers and fortified gates, and he began building a palace complex in the northeastern part of the city. To the south of his palace, he ordered the construction of a large formal audience hall and a massive imperial bathhouse. He sponsored many building projects throughout Gaul during his tenure as emperor of the West, especially in Augustodunum (Autun) and Arelate (Arles).[86] According to Lactantius, Constantine followed a tolerant policy towards Christianity, although he was not yet a Christian himself. He probably judged it a more sensible policy than open persecution[87] and a way to distinguish himself from the "great persecutor" Galerius.[88] He decreed a formal end to persecution and returned to Christians all that they had lost during them.[89]

Constantine was largely untried and had a hint of illegitimacy about him; he relied on his father's reputation in his early propaganda, which gave as much coverage to his father's deeds as to his.[90] His military skill and building projects, however, soon gave the panegyrist the opportunity to comment favourably on the similarities between father and son, and Eusebius remarked that Constantine was a "renewal, as it were, in his own person, of his father's life and reign".[91] Constantinian coinage, sculpture, and oratory also show a new tendency for disdain towards the "barbarians" beyond the frontiers. He minted a coin issue after his victory over the Alemanni which depicts weeping and begging Alemannic tribesmen, "the Alemanni conquered" beneath the phrase "Romans' rejoicing".[92] There was little sympathy for these enemies; as his panegyrist declared, "It is a stupid clemency that spares the conquered foe."[93]

Maxentius' rebellion

Following Galerius' recognition of Constantine as caesar, Constantine's portrait was brought to Rome, as was customary. Maxentius mocked the portrait's subject as the son of a harlot and lamented his own powerlessness.[94] Maxentius, envious of Constantine's authority,[95] seized the title of emperor on 28 October 306 AD. Galerius refused to recognize him but failed to unseat him. Galerius sent Severus against Maxentius, but during the campaign, Severus' armies, previously under command of Maxentius' father Maximian, defected, and Severus was seized and imprisoned.[96] Maximian, brought out of retirement by his son's rebellion, left for Gaul to confer with Constantine in late 307 AD. He offered to marry his daughter Fausta to Constantine and elevate him to augustan rank. In return, Constantine would reaffirm the old family alliance between Maximian and Constantius and offer support to Maxentius' cause in Italy. Constantine accepted and married Fausta in Trier in late summer 307 AD. Constantine now gave Maxentius his meagre support, offering Maxentius political recognition.[97]

Constantine remained aloof from the Italian conflict, however. Over the spring and summer of 307 AD, he had left Gaul for Britain to avoid any involvement in the Italian turmoil;[98] now, instead of giving Maxentius military aid, he sent his troops against Germanic tribes along the Rhine. In 308 AD, he raided the territory of the Bructeri, and made a bridge across the Rhine at Colonia Agrippinensium (Cologne). In 310 AD, he marched to the northern Rhine and fought the Franks. When not campaigning, he toured his lands advertising his benevolence and supporting the economy and the arts. His refusal to participate in the war increased his popularity among his people and strengthened his power base in the West.[99] Maximian returned to Rome in the winter of 307–308 AD, but soon fell out with his son. In early 308 AD, after a failed attempt to usurp Maxentius' title, Maximian returned to Constantine's court.[100]

On 11 November 308 AD, Galerius called a general council at the military city of Carnuntum (Petronell-Carnuntum, Austria) to resolve the instability in the western provinces. In attendance were Diocletian, briefly returned from retirement, Galerius, and Maximian. Maximian was forced to abdicate again and Constantine was again demoted to caesar. Licinius, one of Galerius' old military companions, was appointed augustus in the western regions. The new system did not last long: Constantine refused to accept the demotion, and continued to style himself as augustus on his coinage, even as other members of the Tetrarchy referred to him as a caesar on theirs. Maximinus Daia was frustrated that he had been passed over for promotion while the newcomer Licinius had been raised to the office of augustus and demanded that Galerius promote him. Galerius offered to call both Maximinus and Constantine "sons of the augusti",[101] but neither accepted the new title. By the spring of 310 AD, Galerius was referring to both men as augusti.[102]

Maximian's rebellion

In 310 AD, a dispossessed Maximian rebelled against Constantine while Constantine was away campaigning against the Franks. Maximian had been sent south to Arles with a contingent of Constantine's army, in preparation for any attacks by Maxentius in southern Gaul. He announced that Constantine was dead, and took up the imperial purple. In spite of a large donative pledge to any who would support him as emperor, most of Constantine's army remained loyal to their emperor, and Maximian was soon compelled to leave. Constantine soon heard of the rebellion, abandoned his campaign against the Franks, and marched his army up the Rhine.[104] At Cabillunum (Chalon-sur-Saône), he moved his troops onto waiting boats to row down the slow waters of the Saône to the quicker waters of the Rhone. He disembarked at Lugdunum (Lyon).[105] Maximian fled to Massilia (Marseille), a town better able to withstand a long siege than Arles. It made little difference, however, as loyal citizens opened the rear gates to Constantine. Maximian was captured and reproved for his crimes. Constantine granted some clemency, but strongly encouraged his suicide. In July 310 AD, Maximian hanged himself.[104]

In spite of the earlier rupture in their relations, Maxentius was eager to present himself as his father's devoted son after his death.[106] He began minting coins with his father's deified image, proclaiming his desire to avenge Maximian's death.[107] Constantine initially presented the suicide as an unfortunate family tragedy. By 311 AD, however, he was spreading another version. According to this, after Constantine had pardoned him, Maximian planned to murder Constantine in his sleep. Fausta learned of the plot and warned Constantine, who put a eunuch in his own place in bed. Maximian was apprehended when he killed the eunuch and was offered suicide, which he accepted.[108] Along with using propaganda, Constantine instituted a damnatio memoriae on Maximian, destroying all inscriptions referring to him and eliminating any public work bearing his image.[109]

The death of Maximian required a shift in Constantine's public image. He could no longer rely on his connection to the elder Emperor Maximian, and needed a new source of legitimacy.[110] In a speech delivered in Gaul on 25 July 310 AD, the anonymous orator reveals a previously unknown dynastic connection to Claudius II, a 3rd-century emperor famed for defeating the Goths and restoring order to the empire. Breaking away from tetrarchic models, the speech emphasizes Constantine's ancestral prerogative to rule, rather than principles of imperial equality. The new ideology expressed in the speech made Galerius and Maximian irrelevant to Constantine's right to rule.[111] Indeed, the orator emphasizes ancestry to the exclusion of all other factors: "No chance agreement of men, nor some unexpected consequence of favor, made you emperor," the orator declares to Constantine.[112]

The oration also moves away from the religious ideology of the Tetrarchy, with its focus on twin dynasties of Jupiter and Hercules. Instead, the orator proclaims that Constantine experienced a divine vision of Apollo and Victory granting him laurel wreaths of health and a long reign. In the likeness of Apollo, Constantine recognized himself as the saving figure to whom would be granted "rule of the whole world",[113] as the poet Virgil had once foretold.[114] The oration's religious shift is paralleled by a similar shift in Constantine's coinage. In his early reign, the coinage of Constantine advertised Mars as his patron. From 310 AD on, Mars was replaced by Sol Invictus, a god conventionally identified with Apollo.[115] There is little reason to believe that either the dynastic connection or the divine vision are anything other than fiction, but their proclamation strengthened Constantine's claims to legitimacy and increased his popularity among the citizens of Gaul.[116]

Civil wars

War against Maxentius

By the middle of 310 AD, Galerius had become too ill to involve himself in imperial politics.[117] His final act survives: a letter to provincials posted in Nicomedia on 30 April 311 AD, proclaiming an end to the persecutions, and the resumption of religious toleration.[118] He died soon after the edict's proclamation,[119] destroying what little remained of the tetrarchy.[120] Maximinus mobilized against Licinius, and seized Asia Minor. A hasty peace was signed on a boat in the middle of the Bosphorus.[121] While Constantine toured Britain and Gaul, Maxentius prepared for war.[122] He fortified northern Italy, and strengthened his support in the Christian community by allowing it to elect a new Bishop of Rome, Eusebius.[123]

Maxentius' rule was nevertheless insecure. His early support dissolved in the wake of heightened tax rates and depressed trade; riots broke out in Rome and Carthage;[124] and Domitius Alexander was able to briefly usurp his authority in Africa.[125] By 312 AD, he was a man barely tolerated, not one actively supported,[126] even among Christian Italians.[127] In the summer of 311 AD, Maxentius mobilized against Constantine while Licinius was occupied with affairs in the East. He declared war on Constantine, vowing to avenge his father's "murder".[128] To prevent Maxentius from forming an alliance against him with Licinius,[129] Constantine forged his own alliance with Licinius over the winter of 311–312 AD, and offered him his sister Constantia in marriage. Maximinus considered Constantine's arrangement with Licinius an affront to his authority. In response, he sent ambassadors to Rome, offering political recognition to Maxentius in exchange for a military support. Maxentius accepted.[130] According to Eusebius, inter-regional travel became impossible, and there was military buildup everywhere. There was "not a place where people were not expecting the onset of hostilities every day".[131]

_c1650_by_Lazzaro_Baldi_after_Giulio_Romano_at_the_University_of_Edinburgh.jpg)

Constantine's advisers and generals cautioned against preemptive attack on Maxentius;[132] even his soothsayers recommended against it, stating that the sacrifices had produced unfavourable omens.[133] Constantine, with a spirit that left a deep impression on his followers, inspiring some to believe that he had some form of supernatural guidance,[134] ignored all these cautions.[135] Early in the spring of 312 AD,[136] Constantine crossed the Cottian Alps with a quarter of his army, a force numbering about 40,000.[137] The first town his army encountered was Segusium (Susa, Italy), a heavily fortified town that shut its gates to him. Constantine ordered his men to set fire to its gates and scale its walls. He took the town quickly. Constantine ordered his troops not to loot the town, and advanced with them into northern Italy.[136]

At the approach to the west of the important city of Augusta Taurinorum (Turin, Italy), Constantine met a large force of heavily armed Maxentian cavalry.[138] In the ensuing battle Constantine's army encircled Maxentius' cavalry, flanked them with his own cavalry, and dismounted them with blows from his soldiers' iron-tipped clubs. Constantine's armies emerged victorious.[139] Turin refused to give refuge to Maxentius' retreating forces, opening its gates to Constantine instead.[140] Other cities of the north Italian plain sent Constantine embassies of congratulation for his victory. He moved on to Milan, where he was met with open gates and jubilant rejoicing. Constantine rested his army in Milan until mid-summer 312 AD, when he moved on to Brixia (Brescia).[141]

Brescia's army was easily dispersed,[142] and Constantine quickly advanced to Verona, where a large Maxentian force was camped.[143] Ruricius Pompeianus, general of the Veronese forces and Maxentius' praetorian prefect,[144] was in a strong defensive position, since the town was surrounded on three sides by the Adige. Constantine sent a small force north of the town in an attempt to cross the river unnoticed. Ruricius sent a large detachment to counter Constantine's expeditionary force, but was defeated. Constantine's forces successfully surrounded the town and laid siege.[145] Ruricius gave Constantine the slip and returned with a larger force to oppose Constantine. Constantine refused to let up on the siege, and sent only a small force to oppose him. In the desperately fought encounter that followed, Ruricius was killed and his army destroyed.[146] Verona surrendered soon afterwards, followed by Aquileia,[147] Mutina (Modena),[148] and Ravenna.[149] The road to Rome was now wide open to Constantine.[150]

Maxentius prepared for the same type of war he had waged against Severus and Galerius: he sat in Rome and prepared for a siege.[151] He still controlled Rome's praetorian guards, was well-stocked with African grain, and was surrounded on all sides by the seemingly impregnable Aurelian Walls. He ordered all bridges across the Tiber cut, reportedly on the counsel of the gods,[152] and left the rest of central Italy undefended; Constantine secured that region's support without challenge.[153] Constantine progressed slowly[154] along the Via Flaminia,[155] allowing the weakness of Maxentius to draw his regime further into turmoil.[154] Maxentius' support continued to weaken: at chariot races on 27 October, the crowd openly taunted Maxentius, shouting that Constantine was invincible.[156] Maxentius, no longer certain that he would emerge from a siege victorious, built a temporary boat bridge across the Tiber in preparation for a field battle against Constantine.[157] On 28 October 312 AD, the sixth anniversary of his reign, he approached the keepers of the Sibylline Books for guidance. The keepers prophesied that, on that very day, "the enemy of the Romans" would die. Maxentius advanced north to meet Constantine in battle.[158]

Constantine adopts the Greek letters Chi Rho for Christ's initials

Maxentius' forces were still twice the size of Constantine's, and he organized them in long lines facing the battle plain with their backs to the river.[159] Constantine's army arrived on the field bearing unfamiliar symbols on their standards and their shields.[160] According to Lactantius "Constantine was directed in a dream to cause the heavenly sign to be delineated on the shields of his soldiers, and so to proceed to battle. He did as he had been commanded, and he marked on their shields the letter Χ, with a perpendicular line drawn through it and turned round thus at the top, being the cipher of Christ. Having this sign (☧), his troops stood to arms."[161] Eusebius describes a vision that Constantine had while marching at midday in which "he saw with his own eyes the trophy of a cross of light in the heavens, above the sun, and bearing the inscription, In Hoc Signo Vinces" ("In this sign thou shalt conquer").[162] In Eusebius's account, Constantine had a dream the following night in which Christ appeared with the same heavenly sign and told him to make an army standard in the form of the labarum.[163] Eusebius is vague about when and where these events took place,[164] but it enters his narrative before the war begins against Maxentius.[165] He describes the sign as Chi (Χ) traversed by Rho (Ρ) to form ☧, representing the first two letters of the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Christos).[166][167] A medallion was issued at Ticinum in 315 AD which shows Constantine wearing a helmet emblazoned with the Chi Rho,[168] and coins issued at Siscia in 317/318 AD repeat the image.[169] The figure was otherwise rare and is uncommon in imperial iconography and propaganda before the 320s.[170] It wasn't completely unknown, however, being an abbreviation of the Greek word chrēston (good), having previously appeared on the coins of Ptolemy III, Euergetes I (247-222 BCE).

Constantine deployed his own forces along the whole length of Maxentius' line. He ordered his cavalry to charge, and they broke Maxentius' cavalry. He then sent his infantry against Maxentius' infantry, pushing many into the Tiber where they were slaughtered and drowned.[159] The battle was brief,[171] and Maxentius' troops were broken before the first charge.[172] His horse guards and praetorians initially held their position, but they broke under the force of a Constantinian cavalry charge; they also broke ranks and fled to the river. Maxentius rode with them and attempted to cross the bridge of boats (Ponte Milvio), but he was pushed into the Tiber and drowned by the mass of his fleeing soldiers.[173]

In Rome

Constantine entered Rome on 29 October 312 AD,[175][176] and staged a grand adventus in the city which was met with jubilation.[177] Maxentius' body was fished out of the Tiber and decapitated, and his head was paraded through the streets for all to see.[178] After the ceremonies, the disembodied head was sent to Carthage, and Carthage offered no further resistance.[179] Unlike his predecessors, Constantine neglected to make the trip to the Capitoline Hill and perform customary sacrifices at the Temple of Jupiter.[180] However, he did visit the Senatorial Curia Julia,[181] and he promised to restore its ancestral privileges and give it a secure role in his reformed government; there would be no revenge against Maxentius' supporters.[182] In response, the Senate decreed him "title of the first name", which meant that his name would be listed first in all official documents,[183] and they acclaimed him as "the greatest Augustus".[184] He issued decrees returning property that was lost under Maxentius, recalling political exiles, and releasing Maxentius' imprisoned opponents.[185]

An extensive propaganda campaign followed, during which Maxentius' image was purged from all public places. He was written up as a "tyrant" and set against an idealized image of Constantine the "liberator". Eusebius is the best representative of this strand of Constantinian propaganda.[186] Maxentius' rescripts were declared invalid, and the honours that he had granted to leaders of the Senate were also invalidated.[187] Constantine also attempted to remove Maxentius' influence on Rome's urban landscape. All structures built by him were rededicated to Constantine, including the Temple of Romulus and the Basilica of Maxentius.[188] At the focal point of the basilica, a stone statue was erected of Constantine holding the Christian labarum in its hand. Its inscription bore the message which the statue illustrated: By this sign, Constantine had freed Rome from the yoke of the tyrant.[189]

Constantine also sought to upstage Maxentius' achievements. For example, the Circus Maximus was redeveloped so that its seating capacity was 25 times larger than that of Maxentius' racing complex on the Via Appia.[190] Maxentius' strongest military supporters were neutralized when he disbanded the Praetorian Guard and Imperial Horse Guard.[191] The tombstones of the Imperial Horse Guard were ground up and used in a basilica on the Via Labicana,[192] and their former base was redeveloped into the Lateran Basilica on 9 November 312 AD—barely two weeks after Constantine captured the city.[193] The Legio II Parthica was removed from Albano Laziale,[187] and the remainder of Maxentius' armies were sent to do frontier duty on the Rhine.[194]

Wars against Licinius

In the following years, Constantine gradually consolidated his military superiority over his rivals in the crumbling Tetrarchy. In 313, he met Licinius in Milan to secure their alliance by the marriage of Licinius and Constantine's half-sister Constantia. During this meeting, the emperors agreed on the so-called Edict of Milan,[195] officially granting full tolerance to Christianity and all religions in the Empire.[196] The document had special benefits for Christians, legalizing their religion and granting them restoration for all property seized during Diocletian's persecution. It repudiates past methods of religious coercion and used only general terms to refer to the divine sphere—"Divinity" and "Supreme Divinity", summa divinitas.[197] The conference was cut short, however, when news reached Licinius that his rival Maximinus had crossed the Bosporus and invaded European territory. Licinius departed and eventually defeated Maximinus, gaining control over the entire eastern half of the Roman Empire. Relations between the two remaining emperors deteriorated, as Constantine suffered an assassination attempt at the hands of a character that Licinius wanted elevated to the rank of Caesar;[198] Licinius, for his part, had Constantine's statues in Emona destroyed.[199] In either 314 or 316 AD, the two Augusti fought against one another at the Battle of Cibalae, with Constantine being victorious. They clashed again at the Battle of Mardia in 317, and agreed to a settlement in which Constantine's sons Crispus and Constantine II, and Licinius' son Licinianus were made caesars.[200] After this arrangement, Constantine ruled the dioceses of Pannonia and Macedonia and took residence at Sirmium, whence he could wage war on the Goths and Sarmatians in 322, and on the Goths in 323, defeating and killing their leader Rausimod.[198]

In the year 320, Licinius allegedly reneged on the religious freedom promised by the Edict of Milan in 313 and began to oppress Christians anew,[201] generally without bloodshed, but resorting to confiscations and sacking of Christian office-holders.[202] Although this characterization of Licinius as anti-Christian is somewhat doubtful, the fact is that he seems to have been far less open in his support of Christianity than Constantine. Therefore, Licinius was prone to see the Church as a force more loyal to Constantine than to the Imperial system in general,[203] as the explanation offered by the Church historian Sozomen.[204]

This dubious arrangement eventually became a challenge to Constantine in the West, climaxing in the great civil war of 324. Licinius, aided by Gothic mercenaries, represented the past and the ancient pagan faiths. Constantine and his Franks marched under the standard of the labarum, and both sides saw the battle in religious terms. Outnumbered, but fired by their zeal, Constantine's army emerged victorious in the Battle of Adrianople. Licinius fled across the Bosphorus and appointed Martinian, his magister officiorum, as nominal Augustus in the West, but Constantine next won the Battle of the Hellespont, and finally the Battle of Chrysopolis on 18 September 324.[205] Licinius and Martinian surrendered to Constantine at Nicomedia on the promise their lives would be spared: they were sent to live as private citizens in Thessalonica and Cappadocia respectively, but in 325 Constantine accused Licinius of plotting against him and had them both arrested and hanged; Licinius' son (the son of Constantine's half-sister) was killed in 326.[206] Thus Constantine became the sole emperor of the Roman Empire.[207]

Later rule

Foundation of Constantinople

Licinius' defeat came to represent the defeat of a rival centre of pagan and Greek-speaking political activity in the East, as opposed to the Christian and Latin-speaking Rome, and it was proposed that a new Eastern capital should represent the integration of the East into the Roman Empire as a whole, as a center of learning, prosperity, and cultural preservation for the whole of the Eastern Roman Empire.[208] Among the various locations proposed for this alternative capital, Constantine appears to have toyed earlier with Serdica (present-day Sofia), as he was reported saying that "Serdica is my Rome".[209] Sirmium and Thessalonica were also considered.[210] Eventually, however, Constantine decided to work on the Greek city of Byzantium, which offered the advantage of having already been extensively rebuilt on Roman patterns of urbanism, during the preceding century, by Septimius Severus and Caracalla, who had already acknowledged its strategic importance.[211] The city was thus founded in 324,[212] dedicated on 11 May 330[212] and renamed Constantinopolis ("Constantine's City" or Constantinople in English). Special commemorative coins were issued in 330 to honor the event. The new city was protected by the relics of the True Cross, the Rod of Moses and other holy relics, though a cameo now at the Hermitage Museum also represented Constantine crowned by the tyche of the new city.[213] The figures of old gods were either replaced or assimilated into a framework of Christian symbolism. Constantine built the new Church of the Holy Apostles on the site of a temple to Aphrodite. Generations later there was the story that a divine vision led Constantine to this spot, and an angel no one else could see led him on a circuit of the new walls.[214] The capital would often be compared to the 'old' Rome as Nova Roma Constantinopolitana, the "New Rome of Constantinople".[207][215]

Religious policy

Constantine was the first emperor to stop the persecution of Christians and to legalize Christianity, along with all other religions/cults in the Roman Empire. In February 313, he met with Licinius in Milan and developed the Edict of Milan, which stated that Christians should be allowed to follow their faith without oppression.[216] This removed penalties for professing Christianity, under which many had been martyred previously, and it returned confiscated Church property. The edict protected all religions from persecution, not only Christianity, allowing anyone to worship any deity that they chose. A similar edict had been issued in 311 by Galerius, senior emperor of the Tetrarchy, which granted Christians the right to practise their religion but did not restore any property to them.[217] The Edict of Milan included several clauses which stated that all confiscated churches would be returned, as well as other provisions for previously persecuted Christians. Scholars debate whether Constantine adopted his mother Helena's Christianity in his youth, or whether he adopted it gradually over the course of his life.[218]

Constantine possibly retained the title of pontifex maximus which emperors bore as heads of the ancient Roman religion until Gratian renounced the title.[219][220] According to Christian writers, Constantine was over 40 when he finally declared himself a Christian, making it clear that he owed his successes to the protection of the Christian High God alone.[221] Despite these declarations of being a Christian, he waited to be baptized on his deathbed, believing that the baptism would release him of any sins he committed in the course of carrying out his policies while emperor.[222] He supported the Church financially, built basilicas, granted privileges to clergy (such as exemption from certain taxes), promoted Christians to high office, and returned property confiscated during the long period of persecution.[223] His most famous building projects include the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and Old Saint Peter's Basilica. In constructing the Old Saint Peter's Basilica, Constantine went to great lengths to erect the basilica on top of St. Peter's resting place, so much so that it even affected the design of the basilica, including the challenge of erecting it on the hill where St. Peter rested, making its complete construction time over 30 years from the date Constantine ordered it to be built.

Constantine might not have patronized Christianity alone. He built a triumphal arch in 315 to celebrate his victory in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312) which was decorated with images of the goddess Victoria, and sacrifices were made to pagan gods at its dedication, including Apollo, Diana, and Hercules. Absent from the Arch are any depictions of Christian symbolism. However, the Arch was commissioned by the Senate, so the absence of Christian symbols may reflect the role of the Curia at the time as a pagan redoubt.[224]

In 321, he legislated that the venerable Sunday should be a day of rest for all citizens.[225] In 323, he issued a decree banning Christians from participating in state sacrifices.[226] After the pagan gods had disappeared from his coinage, Christian symbols appeared as Constantine's attributes, the chi rho between his hands or on his labarum,[227] as well on the coin itself.[228]

The reign of Constantine established a precedent for the emperor to have great influence and authority in the early Christian councils, most notably the dispute over Arianism. Constantine disliked the risks to societal stability that religious disputes and controversies brought with them, preferring to establish an orthodoxy.[229] His influence over the Church councils was to enforce doctrine, root out heresy, and uphold ecclesiastical unity; the Church's role was to determine proper worship, doctrines, and dogma.[230]

North African bishops struggled with Christian bishops who had been ordained by Donatus in opposition to Caecilian from 313 to 316. The African bishops could not come to terms, and the Donatists asked Constantine to act as a judge in the dispute. Three regional Church councils and another trial before Constantine all ruled against Donatus and the Donatism movement in North Africa. In 317, Constantine issued an edict to confiscate Donatist church property and to send Donatist clergy into exile.[231] More significantly, in 325 he summoned the First Council of Nicaea, most known for its dealing with Arianism and for instituting the Nicene Creed. He enforced the council's prohibition against celebrating the Lord's Supper on the day before the Jewish Passover, which marked a definite break of Christianity from the Judaic tradition. From then on, the solar Julian Calendar was given precedence over the lunisolar Hebrew Calendar among the Christian churches of the Roman Empire.[232]

Constantine made some new laws regarding the Jews; some of them were unfavorable towards Jews, although they were not harsher than those of his predecessors.[233] It was made illegal for Jews to seek converts or to attack other Jews who had converted to Christianity.[233] They were forbidden to own Christian slaves or to circumcise their slaves.[234][235] On the other hand, Jewish clergy were given the same exemptions as Christian clergy.[233][236]

Administrative reforms

Beginning in the mid-3rd century, the emperors began to favor members of the equestrian order over senators, who had a monopoly on the most important offices of state. Senators were stripped of the command of legions and most provincial governorships, as it was felt that they lacked the specialized military upbringing needed in an age of acute defense needs;[237] such posts were given to equestrians by Diocletian and his colleagues, following a practice enforced piecemeal by their predecessors. The emperors, however, still needed the talents and the help of the very rich, who were relied on to maintain social order and cohesion by means of a web of powerful influence and contacts at all levels. Exclusion of the old senatorial aristocracy threatened this arrangement.

In 326, Constantine reversed this pro-equestrian trend, raising many administrative positions to senatorial rank and thus opening these offices to the old aristocracy; at the same time, he elevated the rank of existing equestrian office-holders to senator, degrading the equestrian order in the process (at least as a bureaucratic rank).[238] The title of perfectissimus was granted only to mid- or low-level officials by the end of the 4th century.

By the new Constantinian arrangement, one could become a senator by being elected praetor or by fulfilling a function of senatorial rank.[239] From then on, holding actual power and social status were melded together into a joint imperial hierarchy. Constantine gained the support of the old nobility with this,[240] as the Senate was allowed itself to elect praetors and quaestors, in place of the usual practice of the emperors directly creating new magistrates (adlectio). An inscription in honor of city prefect (336–337) Ceionius Rufus Albinus states that Constantine had restored the Senate "the auctoritas it had lost at Caesar's time".[241]

The Senate as a body remained devoid of any significant power; nevertheless, the senators had been marginalized as potential holders of imperial functions during the 3rd century but could now dispute such positions alongside more upstart bureaucrats.[242] Some modern historians see in those administrative reforms an attempt by Constantine at reintegrating the senatorial order into the imperial administrative elite to counter the possibility of alienating pagan senators from a Christianized imperial rule;[243] however, such an interpretation remains conjectural, given the fact that we do not have the precise numbers about pre-Constantine conversions to Christianity in the old senatorial milieu. Some historians suggest that early conversions among the old aristocracy were more numerous than previously supposed.[244]

Constantine's reforms had to do only with the civilian administration. The military chiefs had risen from the ranks since the Crisis of the Third Century[245] but remained outside the senate, in which they were included only by Constantine's children.[246]

Monetary reforms

_obverse.jpg)

The third century saw runaway inflation associated with the production of fiat money to pay for public expenses, and Diocletian tried unsuccessfully to re-establish trustworthy minting of silver and billon coins. The failure resided in the fact that the silver currency was overvalued in terms of its actual metal content, and therefore could only circulate at much discounted rates. Constantine stopped minting the Diocletianic "pure" silver argenteus soon after 305, while the billon currency continued to be used until the 360s. From the early 300s on, Constantine forsook any attempts at restoring the silver currency, preferring instead to concentrate on minting large quantities of the gold solidus, 72 of which made a pound of gold. New and highly debased silver pieces continued to be issued during his later reign and after his death, in a continuous process of retariffing, until this bullion minting ceased in 367, and the silver piece was continued by various denominations of bronze coins, the most important being the centenionalis.[247] These bronze pieces continued to be devalued, assuring the possibility of keeping fiduciary minting alongside a gold standard. The author of De Rebus Bellicis held that the rift widened between classes because of this monetary policy; the rich benefited from the stability in purchasing power of the gold piece, while the poor had to cope with ever-degrading bronze pieces.[248] Later emperors such as Julian the Apostate insisted on trustworthy mintings of the bronze currency.[249]

Constantine's monetary policies were closely associated with his religious policies; increased minting was associated with the confiscation of all gold, silver, and bronze statues from pagan temples between 331 and 336 which were declared to be imperial property. Two imperial commissioners for each province had the task of getting the statues and melting them for immediate minting, with the exception of a number of bronze statues that were used as public monuments in Constantinople.[250]

Executions of Crispus and Fausta

Constantine had his eldest son Crispus seized and put to death by "cold poison" at Pola (Pula, Croatia) sometime between 15 May and 17 June 326.[251] In July, he had his wife Empress Fausta (stepmother of Crispus) killed in an overheated bath.[252] Their names were wiped from the face of many inscriptions, references to their lives were eradicated from the literary record, and the memory of both was condemned. Eusebius, for example, edited out any praise of Crispus from later copies of Historia Ecclesiastica, and his Vita Constantini contains no mention of Fausta or Crispus at all.[253] Few ancient sources are willing to discuss possible motives for the events, and the few that do are of later provenance and are generally unreliable.[254] At the time of the executions, it was commonly believed that Empress Fausta was either in an illicit relationship with Crispus or was spreading rumors to that effect. A popular myth arose, modified to allude to the Hippolytus–Phaedra legend, with the suggestion that Constantine killed Crispus and Fausta for their immoralities;[255] the largely fictional Passion of Artemius explicitly makes this connection.[256] The myth rests on slim evidence as an interpretation of the executions; only late and unreliable sources allude to the relationship between Crispus and Fausta, and there is no evidence for the modern suggestion that Constantine's "godly" edicts of 326 and the irregularities of Crispus are somehow connected.[255]

Although Constantine created his apparent heirs "Caesars", following a pattern established by Diocletian, he gave his creations a hereditary character, alien to the tetrarchic system: Constantine's Caesars were to be kept in the hope of ascending to Empire, and entirely subordinated to their Augustus, as long as he was alive.[257] Therefore, an alternative explanation for the execution of Crispus was, perhaps, Constantine's desire to keep a firm grip on his prospective heirs, this—and Fausta's desire for having her sons inheriting instead of their half-brother—being reason enough for killing Crispus; the subsequent execution of Fausta, however, was probably meant as a reminder to her children that Constantine would not hesitate in "killing his own relatives when he felt this was necessary".[258]

Later campaigns

Constantine considered Constantinople his capital and permanent residence. He lived there for a good portion of his later life. In 328 construction was completed on Constantine's Bridge at Sucidava, (today Celei in Romania)[259] in hopes of reconquering Dacia, a province that had been abandoned under Aurelian. In the late winter of 332, Constantine campaigned with the Sarmatians against the Goths. The weather and lack of food cost the Goths dearly: reportedly, nearly one hundred thousand died before they submitted to Rome. In 334, after Sarmatian commoners had overthrown their leaders, Constantine led a campaign against the tribe. He won a victory in the war and extended his control over the region, as remains of camps and fortifications in the region indicate.[260] Constantine resettled some Sarmatian exiles as farmers in Illyrian and Roman districts, and conscripted the rest into the army. The new frontier in Dacia was along the Brazda lui Novac line supported by new castra.[261] Constantine took the title Dacicus maximus in 336.[262]

In the last years of his life, Constantine made plans for a campaign against Persia. In a letter written to the king of Persia, Shapur, Constantine had asserted his patronage over Persia's Christian subjects and urged Shapur to treat them well.[263] The letter is undatable. In response to border raids, Constantine sent Constantius to guard the eastern frontier in 335. In 336, Prince Narseh invaded Armenia (a Christian kingdom since 301) and installed a Persian client on the throne. Constantine then resolved to campaign against Persia himself. He treated the war as a Christian crusade, calling for bishops to accompany the army and commissioning a tent in the shape of a church to follow him everywhere. Constantine planned to be baptized in the Jordan River before crossing into Persia. Persian diplomats came to Constantinople over the winter of 336–337, seeking peace, but Constantine turned them away. The campaign was called off, however, when Constantine became sick in the spring of 337.[264]

Sickness and death

.jpg)

Constantine knew death would soon come. Within the Church of the Holy Apostles, Constantine had secretly prepared a final resting-place for himself.[265] It came sooner than he had expected. Soon after the Feast of Easter 337, Constantine fell seriously ill.[266] He left Constantinople for the hot baths near his mother's city of Helenopolis (Altinova), on the southern shores of the Gulf of Nicomedia (present-day Gulf of İzmit). There, in a church his mother built in honor of Lucian the Apostle, he prayed, and there he realized that he was dying. Seeking purification, he became a catechumen, and attempted a return to Constantinople, making it only as far as a suburb of Nicomedia.[267] He summoned the bishops, and told them of his hope to be baptized in the River Jordan, where Christ was written to have been baptized. He requested the baptism right away, promising to live a more Christian life should he live through his illness. The bishops, Eusebius records, "performed the sacred ceremonies according to custom".[268] He chose the Arianizing bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia, bishop of the city where he lay dying, as his baptizer.[269] In postponing his baptism, he followed one custom at the time which postponed baptism until after infancy.[270] It has been thought that Constantine put off baptism as long as he did so as to be absolved from as much of his sin as possible.[271] Constantine died soon after at a suburban villa called Achyron, on the last day of the fifty-day festival of Pentecost directly following Pascha (or Easter), on 22 May 337.[272]

Although Constantine's death follows the conclusion of the Persian campaign in Eusebius's account, most other sources report his death as occurring in its middle. Emperor Julian the Apostate (a nephew of Constantine), writing in the mid-350s, observes that the Sassanians escaped punishment for their ill-deeds, because Constantine died "in the middle of his preparations for war".[273] Similar accounts are given in the Origo Constantini, an anonymous document composed while Constantine was still living, and which has Constantine dying in Nicomedia;[274] the Historiae abbreviatae of Sextus Aurelius Victor, written in 361, which has Constantine dying at an estate near Nicomedia called Achyrona while marching against the Persians;[275] and the Breviarium of Eutropius, a handbook compiled in 369 for the Emperor Valens, which has Constantine dying in a nameless state villa in Nicomedia.[276] From these and other accounts, some have concluded that Eusebius's Vita was edited to defend Constantine's reputation against what Eusebius saw as a less congenial version of the campaign.[277]

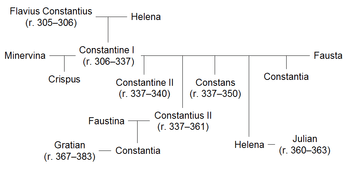

Following his death, his body was transferred to Constantinople and buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles,[278] in a porphyry sarcophagus that was described in the 10th century by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in the De Ceremoniis.[279] His body survived the plundering of the city during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, but was destroyed at some point afterwards.[280] Constantine was succeeded by his three sons born of Fausta, Constantine II, Constantius II and Constans. A number of relatives were killed by followers of Constantius, notably Constantine's nephews Dalmatius (who held the rank of Caesar) and Hannibalianus, presumably to eliminate possible contenders to an already complicated succession. He also had two daughters, Constantina and Helena, wife of Emperor Julian.[281]

Legacy

Saint Constantine the Great | |

|---|---|

mosaics in the Hagia Sophia, section: Maria as patron saint of Constantinople, detail: donor portrait of Emperor Constantine I with a model of the city | |

| Emperor, Confessor and Equal to the Apostles | |

| Resting place | Constantinople modern day Istanbul, Turkey |

| Venerated in |

|

| Major shrine | Church of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople modern day Istanbul, Turkey |

| Feast | 21 May |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Constantine gained his honorific of "the Great" from Christian historians long after he had died, but he could have claimed the title on his military achievements and victories alone. He reunited the Empire under one emperor, and he won major victories over the Franks and Alamanni in 306–308, the Franks again in 313–314, the Goths in 332, and the Sarmatians in 334. By 336, he had reoccupied most of the long-lost province of Dacia which Aurelian had been forced to abandon in 271. At the time of his death, he was planning a great expedition to end raids on the eastern provinces from the Persian Empire.[284] He served for almost 31 years (combining his years as co-ruler and sole ruler), the second longest-serving emperor behind Augustus.

In the cultural sphere, Constantine revived the clean-shaven face fashion of the Roman emperors from Augustus to Trajan, which was originally introduced among the Romans by Scipio Africanus. This new Roman imperial fashion lasted until the reign of Phocas.[285][286]

The Holy Roman Empire reckoned Constantine among the venerable figures of its tradition. In the later Byzantine state, it became a great honor for an emperor to be hailed as a "new Constantine"; ten emperors carried the name, including the last emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire.[287] Charlemagne used monumental Constantinian forms in his court to suggest that he was Constantine's successor and equal. Constantine acquired a mythic role as a warrior against heathens. The motif of the Romanesque equestrian, the mounted figure in the posture of a triumphant Roman emperor, became a visual metaphor in statuary in praise of local benefactors. The name "Constantine" itself enjoyed renewed popularity in western France in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.[288] The Orthodox Church considers Constantine a saint (Άγιος Κωνσταντίνος, Saint Constantine), having a feast day on 21 May,[289] and calls him isapostolos (ισαπόστολος Κωνσταντίνος)—an equal of the Apostles.[290] Although not as celebrated as in Eastern Christianity, he is regarded as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church, with the same feast day.[291]

The Niš Constantine the Great Airport is named in honor of him. A large Cross was planned to be built on a hill overlooking Niš, but the project was cancelled.[292] In 2012, a memorial was erected in Niš in his honor. The Commemoration of the Edict of Milan was held in Niš in 2013.[293]

Historiography

Constantine was presented as a paragon of virtue during his lifetime. Pagans showered him with praise, such as Praxagoras of Athens, and Libanius. His nephew and son-in-law Julian the Apostate, however, wrote the satire Symposium, or the Saturnalia in 361, after the last of his sons died; it denigrated Constantine, calling him inferior to the great pagan emperors, and given over to luxury and greed.[294] Following Julian, Eunapius began—and Zosimus continued—a historiographic tradition that blamed Constantine for weakening the Empire through his indulgence to the Christians.[295]

Constantine was presented as an ideal ruler during the Middle Ages, the standard against which any king or emperor could be measured.[295] The Renaissance rediscovery of anti-Constantinian sources prompted a re-evaluation of his career. German humanist Johannes Leunclavius discovered Zosimus' writings and published a Latin translation in 1576. In its preface, he argued that Zosimus' picture of Constantine offered a more balanced view than that of Eusebius and the Church historians.[296] Cardinal Caesar Baronius criticized Zosimus, favoring Eusebius' account of the Constantinian era. Baronius' Life of Constantine (1588) presents Constantine as the model of a Christian prince.[297] Edward Gibbon aimed to unite the two extremes of Constantinian scholarship in his work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–89) by contrasting the portraits presented by Eusebius and Zosimus.[298] He presents a noble war hero who transforms into an Oriental despot in his old age, "degenerating into a cruel and dissolute monarch".[299]

Modern interpretations of Constantine's rule begin with Jacob Burckhardt's The Age of Constantine the Great (1853, rev. 1880). Burckhardt's Constantine is a scheming secularist, a politician who manipulates all parties in a quest to secure his own power.[300] Henri Grégoire followed Burckhardt's evaluation of Constantine in the 1930s, suggesting that Constantine developed an interest in Christianity only after witnessing its political usefulness. Grégoire was skeptical of the authenticity of Eusebius' Vita, and postulated a pseudo-Eusebius to assume responsibility for the vision and conversion narratives of that work.[301] Otto Seeck's Geschichte des Untergangs der antiken Welt (1920–23) and André Piganiol's L'empereur Constantin (1932) go against this historiographic tradition. Seeck presents Constantine as a sincere war hero whose ambiguities were the product of his own naïve inconsistency.[302] Piganiol's Constantine is a philosophical monotheist, a child of his era's religious syncretism.[303] Related histories by Arnold Hugh Martin Jones (Constantine and the Conversion of Europe, 1949) and Ramsay MacMullen (Constantine, 1969) give portraits of a less visionary and more impulsive Constantine.[304]

These later accounts were more willing to present Constantine as a genuine convert to Christianity. Norman H. Baynes began a historiographic tradition with Constantine the Great and the Christian Church (1929) which presents Constantine as a committed Christian, reinforced by Andreas Alföldi's The Conversion of Constantine and Pagan Rome (1948), and Timothy Barnes's Constantine and Eusebius (1981) is the culmination of this trend. Barnes' Constantine experienced a radical conversion which drove him on a personal crusade to convert his empire.[305] Charles Matson Odahl's Constantine and the Christian Empire (2004) takes much the same tack.[306] In spite of Barnes' work, arguments continue over the strength and depth of Constantine's religious conversion.[307] Certain themes in this school reached new extremes in T.G. Elliott's The Christianity of Constantine the Great (1996), which presented Constantine as a committed Christian from early childhood.[308] Paul Veyne's 2007 work Quand notre monde est devenu chrétien holds a similar view which does not speculate on the origin of Constantine's Christian motivation, but presents him as a religious revolutionary who fervently believed that he was meant "to play a providential role in the millenary economy of the salvation of humanity".[309]

Donation of Constantine

Latin Rite Catholics considered it inappropriate that Constantine was baptized only on his death bed by an unorthodox bishop, as it undermined the authority of the Papacy, and a legend emerged by the early fourth century that Pope Sylvester I (314–335) had cured the pagan emperor from leprosy. According to this legend, Constantine was soon baptized and began the construction of a church in the Lateran Palace.[310] The Donation of Constantine appeared in the eighth century, most likely during the pontificate of Pope Stephen II (752–757), in which the freshly converted Constantine gives "the city of Rome and all the provinces, districts, and cities of Italy and the Western regions" to Sylvester and his successors.[311] In the High Middle Ages, this document was used and accepted as the basis for the Pope's temporal power, though it was denounced as a forgery by Emperor Otto III[312] and lamented as the root of papal worldliness by Dante Alighieri.[313] Philologist and Catholic priest Lorenzo Valla proved that the document was indeed a forgery.[314]

Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia

During the medieval period, Britons regarded Constantine as a king of their own people, particularly associating him with Caernarfon in Gwynedd. While some of this is owed to his fame and his proclamation as Emperor in Britain, there was also confusion of his family with Magnus Maximus's supposed wife Saint Elen and her son, another Constantine (Welsh: Custennin). In the 12th century Henry of Huntingdon included a passage in his Historia Anglorum that the Emperor Constantine's mother was a Briton, making her the daughter of King Cole of Colchester.[315] Geoffrey of Monmouth expanded this story in his highly fictionalized Historia Regum Britanniae, an account of the supposed Kings of Britain from their Trojan origins to the Anglo-Saxon invasion.[316] According to Geoffrey, Cole was King of the Britons when Constantius, here a senator, came to Britain. Afraid of the Romans, Cole submitted to Roman law so long as he retained his kingship. However, he died only a month later, and Constantius took the throne himself, marrying Cole's daughter Helena. They had their son Constantine, who succeeded his father as King of Britain before becoming Roman Emperor.

Historically, this series of events is extremely improbable. Constantius had already left Helena by the time he left for Britain.[42] Additionally, no earlier source mentions that Helena was born in Britain, let alone that she was a princess. Henry's source for the story is unknown, though it may have been a lost hagiography of Helena.[316]

See also

Notes

- With the possible exception of Philip the Arab (r. 244–249). See Philip the Arab and Christianity.[2]

- Constantine was not baptised until just before his death.[4][5]

References

Citations

- Birth dates vary, but most modern historians use "c. 272". Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 59.

- I. Shahîd, Rome and the Arabs (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 1984), 65–93; H. A. Pohlsander, "Philip the Arab and Christianity", Historia 29:4 (1980): 463–73.

- Norwich, John Julius (1996). Byzantium (First American ed.). New York. pp. 54–57. ISBN 0394537785. OCLC 18164817.

- "Constantine the Great". About.com. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- Harris, Jonathan (2017). Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium (2nd ed.). Bloomsbury Academic. p. 38. ISBN 9781474254670.

- Gregory, A History of Byzantium, 49.

- Van Dam, Remembering Constantine at the Milvian Bridge, 30.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, p. 272.

- Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), p. 14; Cameron, p. 90–91; Lenski, "Introduction" (CC), 2–3.

- Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), p. 23–25; Cameron, 90–91; Southern, 169.

- Cameron, 90; Southern, 169.

- Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), 14; Corcoran, Empire of the Tetrarchs, 1; Lenski, "Introduction" (CC), 2–3.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius265–68.

- Drake, "What Eusebius Knew," 21.

- Eusebius, Vita Constantini 1.11; Odahl, 3.

- Lenski, "Introduction" (CC), 5; Storch, 145–55.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 265–71; Cameron, 90–92; Cameron and Hall, 4–6; Elliott, "Eusebian Frauds in the "Vita Constantini"", 162–71.

- Lieu and Montserrat, 39; Odahl, 3.

- Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), 26; Lieu and Montserrat, 40; Odahl, 3.

- Lieu and Montserrat, 40; Odahl, 3.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 12–14; Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), 24; Mackay, 207; Odahl, 9–10.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 225; Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), 28–30; Odahl, 4–6.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 225; Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), 26–29; Odahl, 5–6.

- Odahl, 6, 10.

- Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), 27–28; Lieu and Montserrat, 2–6; Odahl, 6–7; Warmington, 166–67.

- Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), 24; Odahl, 8; Wienand, Kaiser als Sieger, 26–43.

- Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), 20–21; Johnson, "Architecture of Empire" (CC), 288–91; Odahl, 11–12.

- Bleckmann, "Sources for the History of Constantine" (CC), 17–21; Odahl, 11–14; Wienand, Kaiser als Sieger, 43–86.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 3, 39–42; Elliott, Christianity of Constantine, 17; Odahl, 15; Pohlsander, "Constantine I"; Southern, 169, 341.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 3; Barnes, New Empire, 39–42; Elliott, "Constantine's Conversion," 425–6; Elliott, "Eusebian Frauds," 163; Elliott, Christianity of Constantine, 17; Jones, 13–14; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 59; Odahl, 16; Pohlsander, Emperor Constantine, 14; Rodgers, 238; Wright, 495, 507.

- Odahl, Charles M. (2001). Constantine and the Christian empire. London: Routledge. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-415-17485-5.

- Gabucci, Ada (2002). Ancient Rome : art, architecture and history. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-89236-656-9.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 3; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 59–60; Odahl, 16–17.

- fMacMullen, Constantine, 21.

- Panegyrici Latini 8(5), 9(4); Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum 8.7; Eusebius, Vita Constantini 1.13.3; Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 13, 290.

- Drijvers, J.W. Helena Augusta: The Mother of Constantine the Great and the Legend of Her finding the True Cross (Leiden, 1991) 9, 15–17.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 3; Barnes, New Empire, 39–40; Elliott, Christianity of Constantine, 17; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 59, 83; Odahl, 16; Pohlsander, Emperor Constantine, 14.

- Tejirian, Eleanor H.; Simon, Reeva Spector (2012). Conflict, conquest, and conversion two thousand years of Christian missions in the Middle East. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-231-51109-4.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, p. 8–14; Corcoran, "Before Constantine" (CC), 41–54; Odahl, 46–50; Treadgold, 14–15.

- Bowman, p. 70; Potter, 283; Williams, 49, 65.

- Potter, 283; Williams, 49, 65.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 3; Elliott, Christianity of Constantine, 20; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 59–60; Odahl, 47, 299; Pohlsander, Emperor Constantine, 14.

- Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum 7.1; Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 13, 290.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 3, 8; Corcoran, "Before Constantine" (CC), 40–41; Elliott, Christianity of Constantine, 20; Odahl, 46–47; Pohlsander, Emperor Constantine, 8–9, 14; Treadgold, 17.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 8–9; Corcoran, "Before Constantine" (CC), 42–43, 54.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 3; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 59–60; Odahl, 56–7.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 73–74; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 60; Odahl, 72, 301.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 47, 73–74; Fowden, "Between Pagans and Christians," 175–76.

- Constantine, Oratio ad Sanctorum Coetum, 16.2; Elliott, Christianity of Constantine., 29–30; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 60; Odahl, 72–73.

- Elliott, Christianity of Constantine, 29; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 61; Odahl, 72–74, 306; Pohlsander, Emperor Constantine, 15. Contra: J. Moreau, Lactance: "De la mort des persécuteurs", Sources Chrétiennes 39 (1954): 313; Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 297.

- Constantine, Oratio ad Sanctorum Coetum 25; Elliott, Christianity of Constantine, 30; Odahl, 73.

- Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum 10.6–11; Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 21; Elliott, Christianity of Constantine, 35–36; MacMullen, Constantine, 24; Odahl, 67; Potter, 338.

- Eusebius, Vita Constantini 2.49–52; Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 21; Odahl, 67, 73, 304; Potter, 338.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 22–25; MacMullen, Constantine, 24–30; Odahl, 67–69; Potter, 337.

- MacMullen, Constantine, 24–25.

- Oratio ad Sanctorum Coetum 25; Odahl, 73.

- Drake, "The Impact of Constantine on Christianity" (CC), 126; Elliott, "Constantine's Conversion," 425–26.

- Drake, "The Impact of Constantine on Christianity" (CC), 126.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 25–27; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 60; Odahl, 69–72; Pohlsander, Emperor Constantine, 15; Potter, 341–342.

- Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum 19.2–6; Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 26; Potter, 342.

- Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 60–61; Odahl, 72–74; Pohlsander, Emperor Constantine, 15.

- Origo 4; Lactantius, De Mortibus Persecutorum 24.3–9; Praxagoras fr. 1.2; Aurelius Victor 40.2–3; Epitome de Caesaribus 41.2; Zosimus 2.8.3; Eusebius, Vita Constantini 1.21; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 61; MacMullen, Constantine, 32; Odahl, 73.

- Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 61.

- Odahl, 75–76.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 27; Elliott, Christianity of Constantine, 39–40; Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 61; MacMullen, Constantine, 32; Odahl, 77; Pohlsander, Emperor Constantine, 15–16; Potter, 344–5; Southern, 169–70, 341.

- MacMullen, Constantine, 32.