Heraclius

Flavius Heraclius (Greek: Φλάβιος Ἡράκλειος, Flavios Iraklios; c. 575 – February 11, 641) was the Emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revolt against the unpopular usurper Phocas.

| Heraclius | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor of the Romans | |||||||||

Solidus of Emperor Heraclius (aged 35–38). Constantinople mint. Struck 610–613. Helmeted and cuirassed facing bust, holding cross. | |||||||||

| Emperor of the Byzantine Empire | |||||||||

| Reign | October 5, 610 – February 11, 641 | ||||||||

| Coronation | October 5, 610 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Phocas | ||||||||

| Successor | Constantine III Heraklonas | ||||||||

| Co-emperors | Constantine III (613–641) Heraklonas (638–641) | ||||||||

| Born | c. 575 Cappadocia, present-day Turkey | ||||||||

| Died | February 11, 641 (aged 65 or 66) Constantinople, Byzantine Empire | ||||||||

| Spouse | Eudokia Martina | ||||||||

| Issue | Constantine III Heraklonas John Athalarichos (illegitimate) Martinos Tiberius | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Heraclian Dynasty | ||||||||

| Father | Heraclius the Elder | ||||||||

| Mother | Epiphania | ||||||||

| Heraclian dynasty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chronology | ||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Succession | ||

|

||

Heraclius's reign was marked by several military campaigns. The year Heraclius came to power, the empire was threatened on multiple frontiers. Heraclius immediately took charge of the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. The first battles of the campaign ended in defeat for the Byzantines; the Persian army fought their way to the Bosphorus but Constantinople was protected by impenetrable walls and a strong navy, and Heraclius was able to avoid total defeat. Soon after, he initiated reforms to rebuild and strengthen the military. Heraclius drove the Persians out of Asia Minor and pushed deep into their territory, defeating them decisively in 627 at the Battle of Nineveh. The Persian king Khosrow II was overthrown and executed by his son Kavad II, who soon sued for a peace treaty, agreeing to withdraw from all occupied territory. This way peaceful relations were restored to the two deeply strained empires.

Heraclius lost many of his newly-regained lands to the Muslim conquests. Emerging from the Arabian Peninsula, the Muslims quickly conquered the Sasanian Empire. In 634 the Muslims marched into Roman Syria, defeating Heraclius's brother Theodore. Within a short period of time, the Arabs conquered Mesopotamia, Armenia and Egypt.

Heraclius entered diplomatic relations with the Croats and Serbs in the Balkans. He tried to repair the schism in the Christian church in regard to the Monophysites, by promoting a compromise doctrine called Monothelitism. The Church of the East (commonly called Nestorian) was also involved in the process.[1] Eventually this project of unity was rejected by all sides of the dispute.

Early life

Origins

Heraclius was the eldest son of Heraclius the Elder and Epiphania, of a family of possible Armenian origin from Cappadocia,[A 1][2] with speculative Arsacid descent.[3] Beyond that, there is little specific information known about his ancestry. His father was a key general during Emperor Maurice's war with Bahram Chobin, usurper of the Sasanian Empire, during 590.[4] After the war, Maurice appointed Heraclius the Elder to the position of Exarch of Africa.[4]

Revolt against Phocas and accession

In 608, Heraclius the Elder renounced his loyalty to the Emperor Phocas, who had overthrown Maurice six years earlier. The rebels issued coins showing both Heraclii dressed as consuls, though neither of them explicitly claimed the imperial title at this time.[5] Heraclius's younger cousin Nicetas launched an overland invasion of Egypt; by 609, he had defeated Phocas's general Bonosus and secured the province. Meanwhile, the younger Heraclius sailed eastward with another force via Sicily and Cyprus.[5]

As he approached Constantinople, he made contact with prominent leaders and planned an attack to overthrow aristocrats in the city, and soon arranged a ceremony where he was crowned and acclaimed as Emperor. When he reached the capital, the Excubitors, an elite Imperial Guard unit led by Phocas's son-in-law Priscus, deserted to Heraclius, and he entered the city without serious resistance. When Heraclius captured Phocas, he asked him "Is this how you have ruled, wretch?" Phocas's reply—"And will you rule better?"—so enraged Heraclius that he beheaded Phocas on the spot.[6] He later had the genitalia removed from the body because Phocas had raped the wife of Photius, a powerful politician in the city.[7]

On October 5, 610, Heraclius was crowned for a second time, this time in the Chapel of St. Stephen within the Great Palace; at the same time he married Fabia, who took the name Eudokia. After her death in 612, he married his niece Martina in 613; this second marriage was considered incestuous and was very unpopular.[8] In the reign of Heraclius's two sons, the divisive Martina was to become the center of power and political intrigue. Despite widespread hatred for Martina in Constantinople, Heraclius took her on campaigns with him and refused attempts by Patriarch Sergius to prevent and later dissolve the marriage.[8]

Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628

Initial Persian advantage

During his Balkan Campaigns, Emperor Maurice and his family were murdered by Phocas in November 602 after a mutiny.[9] Khosrow II (Chosroes) of the Sasanian Empire had been restored to his throne by Maurice, and they had remained allies until the latter's death.[A 2] Thereafter, Khosrow seized the opportunity to attack the Byzantine Empire and reconquer Mesopotamia.[10] Khosrow had at his court a man who claimed to be Maurice's son Theodosius, and Khosrow demanded that the Byzantines accept this Theodosius as Emperor.

The war initially went the Persians' way, partly because of Phocas's brutal repression and the succession crisis that ensued as the general Heraclius sent his nephew Nicetas to attack Egypt, enabling his son Heraclius the younger to claim the throne in 610.[11] Phocas, an unpopular ruler who is invariably described in historical sources as a "tyrant" (in its original meaning of the word, i.e. illegitimate king by the rules of succession), was eventually deposed by Heraclius, who sailed to Constantinople from Carthage with an icon affixed to the prow of his ship.[12][13]

By this time, the Persians had conquered Mesopotamia and the Caucasus, and in 611 they overran Syria and entered Anatolia. A major counter-attack led by Heraclius two years later was decisively defeated outside Antioch by Shahrbaraz and Shahin, and the Roman position collapsed; the Persians devastated parts of Asia Minor and captured Chalcedon across from Constantinople on the Bosporus.[14]

Over the following decade the Persians were able to conquer Palestine and Egypt (by mid-621 the whole province was in their hands)[15] and to devastate Anatolia,[A 3] while the Avars and Slavs took advantage of the situation to overrun the Balkans, bringing the Empire to the brink of destruction. In 613, the Persian army took Damascus with the help of the Jews, seized Jerusalem in 614, damaging the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and capturing the True Cross, and afterwards capturing Egypt in 617 or 618.[17] When the Sasanians reached Chalcedon in 615, it was at this point, according to Sebeos, that Heraclius had agreed to stand down and was about ready to allow the Byzantine Empire to become a Persian client state, even permitting Khosrow II to choose the emperor.[18] In a letter delivered by his ambassadors, Heraclius acknowledged the Persian empire as superior, described himself as Khosrow II's "obedient son, one who is eager to perform the services of your serenity in all things," and even called Khosrow II the "supreme emperor."[19] Khosrow II nevertheless rejected the peace offer, and arrested Heraclius' ambassadors.[20]

With the Persians at the very gate of Constantinople, Heraclius thought of abandoning the city and moving the capital to Carthage, but the powerful church figure Patriarch Sergius convinced him to stay. Safe behind the walls of Constantinople, Heraclius was able to sue for peace in exchange for an annual tribute of a thousand talents of gold, a thousand talents of silver, a thousand silk robes, a thousand horses, and a thousand virgins to the Persian King.[21] The peace allowed him to rebuild the Empire's army by slashing non-military expenditure, devaluing the currency, and melting down, with the backing of Patriarch Sergius, Church treasures to raise the necessary funds to continue the war.[22]

Byzantine counter-offensive and resurgence

On April 5, 622, Heraclius left Constantinople, entrusting the city to Sergius and general Bonus as regents of his son. He assembled his forces in Asia Minor, probably in Bithynia, and, after he revived their broken morale, he launched a new counter-offensive, which took on the character of a holy war; an acheiropoietos image of Christ was carried as a military standard.[22][23][24][25]

The Roman army proceeded to Armenia, inflicted a defeat on an army led by a Persian-allied Arab chief, and then won a victory over the Persians under Shahrbaraz.[26] Heraclius would stay on campaign for several years.[27][28] On March 25, 624 he again left Constantinople with his wife, Martina, and his two children; after he celebrated Easter in Nicomedia on April 15, he campaigned in the Caucasus, winning a series of victories in Armenia against Khosrow and his generals Shahrbaraz, Shahin, and Shahraplakan.[29][30] In the same year the Visigoths succeeded in recapturing Cartagena, capital of the western Byzantine province of Spania, resulting in the loss of one of the few minor provinces that had been conquered by the armies of Justinian I.[31] In 626 the Avars and Slavs supported by a Persian army commanded by Shahrbaraz, besieged Constantinople, but the siege ended in failure (the victory was attributed to the icons of the Virgin which were led in procession by Sergius about the walls of the city),[32] while a second Persian army under Shahin suffered another crushing defeat at the hands of Heraclius's brother Theodore.

With the Persian war effort disintegrating, Heraclius was able to bring the Gokturks of the Western Turkic Khaganate, under Ziebel, who invaded Persian Transcaucasia. Heraclius exploited divisions within the Persian Empire, keeping Shahrbaraz neutral by convincing him that Khosrow had grown jealous of him and had ordered his execution. Late in 627 he launched a winter offensive into Mesopotamia, where, despite the desertion of his Turkish allies, he defeated the Persians under Rhahzadh at the Battle of Nineveh.[33] Continuing south along the Tigris he sacked Khosrow's great palace at Dastagird and was only prevented from attacking Ctesiphon by the destruction of the bridges on the Nahrawan Canal. Discredited by this series of disasters, Khosrow was overthrown and killed in a coup led by his son Kavad II, who at once sued for peace, agreeing to withdraw from all occupied territories.[34] In 629 Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem in a majestic ceremony.[13][35][36]

Heraclius took for himself the ancient Persian title of "King of Kings" after his victory. Later on, starting in 629, he styled himself as Basileus, the Greek word for "sovereign", and that title was used by the Byzantine Emperors for the next 800 years. The reason Heraclius chose this title over previous Roman terms such as Augustus has been attributed by some scholars to his Armenian origins.[37]

Heraclius's defeat of the Persians ended a war that had been going on intermittently for almost 400 years and led to instability in the Persian Empire. Kavad II died only months after assuming the throne, plunging Persia into several years of dynastic turmoil and civil war. Ardashir III, Heraclius's ally Shahrbaraz, and Khosrow's daughters Boran and Azarmidokht all succeeded to the throne within months of each other. Only when Yazdgerd III, a grandson of Khosrow II, succeeded to the throne in 632 was there stability. But by then the Sasanid Empire was severely disorganised, having been weakened by years of war and civil strife over the succession to the throne.[38][39] The war had been devastating, and left the Byzantines in a much-weakened state. Within a few years both empires were overwhelmed by the onslaught of the Arabs, who had become newly united by Islam,[40] ultimately leading to the Muslim conquest of Persia and the fall of the Sasanian dynasty in 651.[41]

War against the Arabs

.svg.png)

By 629, the Islamic Prophet Muhammad had unified all the tribes of the Arabian Peninsula, previously too divided to pose a serious military challenge to the Byzantines or the Persians. Now animated by their conversion to Islam, they comprised one of the most powerful states in the region.[42] The first conflict between the Byzantines and Muslims was the Battle of Mu'tah in September 629. A small Muslim skirmishing force attacked the province of Arabia in response to the Muslim ambassador's death at the hands of the Ghassanid Roman governor, but were repulsed. Because the engagement was a Byzantine victory, there was no apparent reason to make changes to the military organization of the region.[43] Also, the Byzantines had little battlefield experience with the Arabs, and even less with zealous soldiers united by a prophet.[44] Even the Strategicon of Maurice, a manual of war praised for the variety of enemies it covers, does not mention warfare against Arabs at any length.[44]

The following year the Muslims launched an offensive into the Arabah south of Lake Tiberias, taking Al Karak. Other raids penetrated into the Negev, reaching as far as Gaza.[45] The Battle of Yarmouk in 636 resulted in a crushing defeat for the larger Byzantine army; within three years, the Levant had been lost again. By the time of Heraclius's death in Constantinople, on February 11, 641, most of Egypt had fallen as well.[46]

Legacy

Looking back at the reign of Heraclius, scholars have credited him with many accomplishments. He enlarged the Empire, and his reorganization of the government and military were great successes. His attempts at religious harmony failed, but he succeeded in returning the True Cross, one of the holiest Christian relics, to Jerusalem.

Accomplishments

Although the territorial gains produced by his defeat of the Persians were lost to the advance of the Muslims, Heraclius still ranks among the great Roman Emperors. His reforms of the government reduced the corruption which had taken hold in Phocas's reign, and he reorganized the military with great success. Ultimately, the reformed Imperial army halted the Muslims in Asia Minor and held on to Carthage for another 60 years, saving a core from which the empire's strength could be rebuilt.[47]

The recovery of the eastern areas of the Roman Empire from the Persians once again raised the problem of religious unity centering on the understanding of the true nature of Christ. Most of the inhabitants of these provinces were Monophysites who rejected the Council of Chalcedon.[48] Heraclius tried to promote a compromise doctrine called Monothelitism but this philosophy was rejected as heretical by both sides of the dispute. For this reason, Heraclius was viewed as a heretic and bad ruler by some later religious writers. After the Monophysite provinces were finally lost to the Muslims, Monotheletism rather lost its raison d'être and was eventually abandoned.[48]

One of the most important legacies of Heraclius was changing the official language of the Empire from Latin to Greek in 610.[49] The Croats and Serbs of Byzantine Dalmatia initiated diplomatic relations and dependencies with Heraclius.[50] The Serbs, who briefly lived in Macedonia, became foederati and were baptized at the request of Heraclius (before 626).[50][51] At his request, Pope John IV (640–642) sent Christian teachers and missionaries to Duke Porga and his Croats, who practiced Slavic paganism.[52] He also created the office of sakellarios, a comptroller of the treasury.[53]

Up to the 20th century he was credited with establishing the Thematic system but modern scholarship now points more to the 660s, under Constans II.[54]

Edward Gibbon, in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, wrote:

Of the characters conspicuous in history, that of Heraclius is one of the most extraordinary and inconsistent. In the first and last years of a long reign, the emperor appears to be the slave of sloth, of pleasure, or of superstition, the careless and impotent spectator of the public calamities. But the languid mists of the morning and evening are separated by the brightness of the meridian sun; the Arcadius of the palace arose the Caesar of the camp; and the honor of Rome and Heraclius was gloriously retrieved by the exploits and trophies of six adventurous campaigns. [...] Since the days of Scipio and Hannibal, no bolder enterprise has been attempted than that which Heraclius achieved for the deliverance of the empire.[55]

Recovery of the True Cross

Heraclius was long remembered favourably by the Western church for his reputed recovery of the True Cross from the Persians. As Heraclius approached the Persian capital during the final stages of the war, Khosrow fled from his favourite residence, Dastagird near Baghdad, without offering resistance. Meanwhile, some of the Persian grandees freed Khosrow's eldest son Kavad II, who had been imprisoned by his father, and proclaimed him King on the night of February 23–24, 628.[56] Kavad, however, was mortally ill and was anxious that Heraclius should protect his infant son Ardeshir. So, as a goodwill gesture, he sent the True Cross with a negotiator in 628.[34]

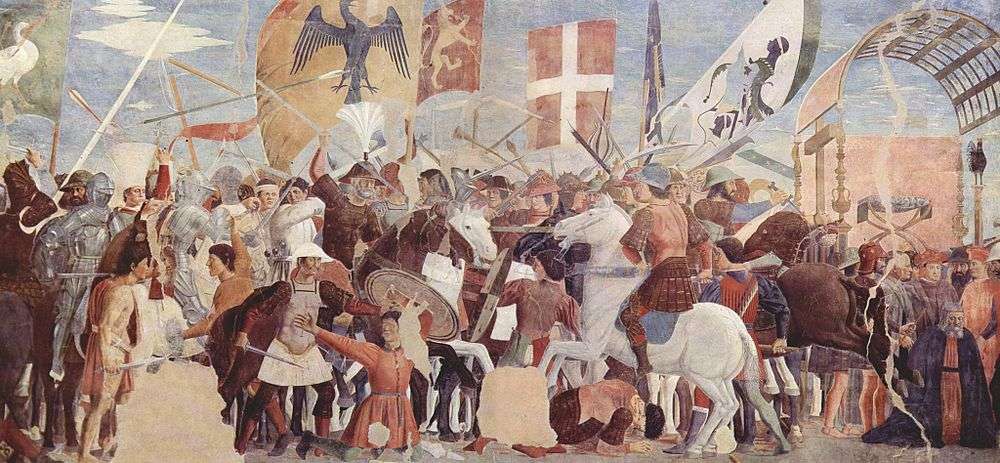

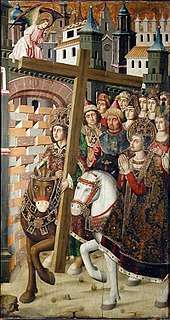

After a tour of the Empire, Heraclius returned the cross to Jerusalem on March 21, 629 or 630.[57][58] For Christians of Western Medieval Europe, Heraclius was the "first crusader". The iconography of the emperor appeared in the sanctuary at Mont Saint-Michel (ca. 1060),[59] and then it became popular, especially in France, the Italian Peninsula, and the Holy Roman Empire.[60] The story was included in the Golden Legend, the famous 13th-century compendium of hagiography, and he is sometimes shown in art, as in The History of the True Cross sequence of frescoes painted by Piero della Francesca in Arezzo, and a similar sequence on a small altarpiece by Adam Elsheimer (Städel, Frankfurt). Both of these show scenes of Heraclius and Constantine I's mother Saint Helena, traditionally responsible for the excavation of the cross. The scene usually shown is Heraclius carrying the cross; according to the Golden Legend, he insisted on doing this as he entered Jerusalem, against the advice of the Patriarch. At first, when he was on horseback (shown above), the burden was too heavy, but after he dismounted and removed his crown it became miraculously light, and the barred city gate opened of its own accord.

Probably because he was one of the few Eastern Roman Emperors widely known in the West, the Late Antique Colossus of Barletta was considered to depict Heraclius.

Some scholars disagree with this narrative, Professor Constantin Zuckerman going as far as to suggest that the True Cross was actually lost, and that the wood contained in the allegedly-still-sealed reliquary brought to Jerusalem by Heraclius in 629 was a fake. In his analysis, the hoax was designed to serve the political purposes of both Heraclius and his former foe, the Persian general Shahrbaraz.[58]

Islamic view of Heraclius

In Surah 30, the Qur'an refers to the Roman-Sasanian wars as follows:

30:2 The Romans have been defeated 3 In the nearest land. But they, after their defeat, will overcome. 4 in a few years..[61]

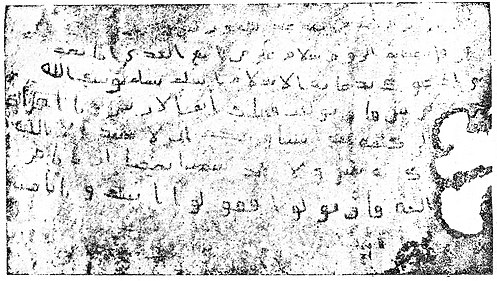

In Islamic and Arab histories Heraclius is the only Roman Emperor who is discussed at any length.[62] Owing to his role as the Roman Emperor at the time Islam emerged, he was remembered in Arabic literature, such as the Islamic hadith and sira.

The Swahili Utendi wa Tambuka, an epic poem composed in 1728 at Pate Island (off the shore of present-day Kenya) and depicting the wars between the Muslims and Byzantines from the former's point of view, is also known as Kyuo kya Hereḳali ("The Book of Heraclius"). In that work, Heraclius is portrayed as declining the Prophet's request to renounce his belief in Christianity; he is therefore defeated by the Muslim forces.[63]

In Muslim tradition he is seen as a just ruler of great piety, who had direct contact with the emerging Islamic forces.[64] The 14th-century scholar Ibn Kathir (d. 1373) went even further, stating that "Heraclius was one of the wisest men and among the most resolute, shrewd, deep and opinionated of kings. He ruled the Romans with great leadership and splendor."[62] Historians such as Nadia Maria El-Cheikh and Lawrence Conrad note that Islamic histories even go so far as claiming that Heraclius recognized Islam as the true faith and Muhammad as its prophet, by comparing Islam to Christianity.[65][66][67]

Islamic historians often cite a letter that they claim Heraclius wrote to Muhammad: "I have received your letter with your ambassador and I testify that you are the messenger of God found in our New Testament. Jesus, son of Mary, announced you."[64] According to the Muslim sources reported by El-Cheikh, he tried to convert the ruling class of the Empire, but they resisted so strongly that he reversed his course and claimed that he was just testing their faith in Christianity.[68] El-Cheikh notes that these accounts of Heraclius add "little to our historical knowledge" of the emperor; rather, they are an important part of "Islamic kerygma," attempting to legitimize Muhammad's status as a prophet.[69]

Most scholarly historians view such traditions as "profoundly kerygmatic" and that "enormous difficulties" exist in using these sources for actual history.[70] Furthermore, they argue that any messengers sent by Muhammad to Heraclius would not have received an imperial audience or recognition.[71] Outside of Islamic sources there is no evidence to suggest Heraclius ever heard of Islam.[72] and it is possible that he and his advisors actually viewed the Muslims as some special sect of Jews.[44]

Family

Heraclius was married twice: first to Fabia Eudokia, a daughter of Rogatus, and then to his niece Martina. He had two children with Fabia (Eudoxia Epiphania and Emperor Constantine III) and at least nine with Martina, most of whom were sickly children.[A 4][76] Of Martina's children at least two were disabled, which was seen as punishment for the illegality of the marriage: Fabius (Flavius) had a paralyzed neck and Theodosios was a deaf-mute. The latter married Nike, daughter of the Persian general Shahrbaraz, or daughter of Niketas, cousin of Heraclius.

Two of Heraclius's children would become Emperor: Heraclius Constantine (Constantine III), his son from Eudokia, for four months in 641, and Martina's son Constantine Heraclius (Heraklonas), in 638–641.[76]

Heraclius had at least one illegitimate son, John Athalarichos, who conspired against Heraclius with his cousin, the magister Theodorus, and the Armenian noble David Saharuni.[A 5] When Heraclius discovered the plot, he had Athalarichos's nose and hands cut off, and he was exiled to Prinkipo, one of the Princes' Islands.[80] Theodorus had the same treatment but was sent to Gaudomelete (possibly modern-day Gozo Island) with additional instructions to cut off one leg.[80]

During the last years of Heraclius's life, it became evident that a struggle was taking place between Heraclius Constantine and Martina, who was trying to position her son Heraklonas to assume the throne. When Heraclius died, he devised the empire to both Heraclius Constantine and Heraklonas to rule jointly with Martina as Empress.[76]

Family tree

See also

- Cathedral of Mren

- Flavia (gens)

- List of Byzantine emperors

- Non-Muslim interactants with Muslims during Muhammad's era

- Revolt against Heraclius

Annotations

- His father referred to retrospectively as Heraclius the Elder.

- Also referred to as Khosrow II, Chosroes II, or Xosrov II in classical sources, sometimes called Parvez, "the Ever Victorious" (in Persian: خسرو پرویز).

- The mint of Nicomedia ceased operating in 613, and Rhodes fell to the invaders in 622/623.[16]

- The number and order of Heraclius's children by Martina is unsure, with some sources saying nine children[74] and others ten.[75]

- The illegitimate son is recorded by a number of different spellings including: Atalarichos,[77] Athalaric,[78] At'alarik,[79] etc.

References

- Seleznyov N.N. "Heraclius and Ishoʿyahb II" Archived January 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Simvol 61: Syriaca-Arabica-Iranica. (Paris-Moscow, 2012), pp. 280–300.

- Treadgold 1997, p. 287.

- "Sasanian Dynasty". Encyclopædia Iranica. July 20, 2005. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- Kaegi 2003, pp. 24–25.

- Mitchell 2007, p. 411.

- Olster 1993, p. 133.

- Charles 2007, p. 177.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 106.

- Gibbon 1994, chap. 46, ii.902.

- Foss 1975, p. 722.

- Gibbon 1994, ii.906.

- Haldon 1997, p. 41.

- Speck 1984, p. 178.

- Greatrex-Lieu 2002, pp. II, 194–195.

- Greatrex-Lieu 2002, p. II, 196.

- Greatrex-Lieu 2002, p. II, 197.

- Gibbon 1994, ii.908–909.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh, author. (March 30, 2017). Decline and fall of the Sasanian empire : the Sasanian-Parthian confederacy and the Arab conquest of Iran. p. 141. ISBN 9781784537470. OCLC 953439586.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Fidler, Richard, 1964- author. (November 13, 2018). Ghost empire : a journey to the legendary Constantinople. p. 159. ISBN 1681779013. OCLC 1023526060.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Fidler, Richard, 1964- author. (November 13, 2018). Ghost empire : a journey to the legendary Constantinople. p. 159. ISBN 1681779013. OCLC 1023526060.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gibbon 1994, chap. 46, ii.914.

- Greatrex-Lieu 2002, p. II, 198.

- Theophanes 1997, pp. 303.12–304.13.

- Cameron 1979, p. 23.

- Grabar 1984, p. 37.

- Treadgold 1997, p. 294.

- Theophanes 1997, pp. 304.25–306.7.

- Greatrex-Lieu 2002, p. II, 199.

- Theophanes 1997, pp. 307.19–308.25.

- Greatrex-Lieu 2002, pp. II, 202–205.

- The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, article Cartagena, p. 384.

- Cameron 1979, pp. 5–6, 20–22.

- Treadgold 1997, p. 298.

- Baynes 1912, p. 288.

- Baynes 1912, passim.

- Haldon 1997, p. 46.

- Kouymjian 1983, pp. 635–642.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 227.

- Beckwith 2009, p. 121.

- Foss 1975, pp. 746–747.

- Milani 2004, p. 15.

- Lewis 2002, pp. 43–44.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 231.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 230.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 233.

- Franzius.

- Collins 2004, p. 128.

- Bury 2005, p. 251.

- Davis 1990, p. 260.

- Kaegi, p. 319.

- De Administrando Imperio, ch. 32 [Of the Serbs and of the country they now dwell in.]: "the emperor brought elders from Rome and baptized them and taught them fairly to perform the works of piety and expounded to them the faith of the Christians."

- Deanesly 1969, p. 491.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 227.

- Haldon 1997, pp. 208ff.

- Gibbon 1994, chap. 46, ii.914, 918.

- Thomson 1999, p. 221.

- Frolow 1953, pp. 88–105.

- Zuckerman, Constantin (2013). Heraclius and the return of the Holy Cross. Constructing the Seventh Century. Travaux et mémoires. Paris: Association des amis du Centre d'histoire et civilisation de Byzance. pp. 197–218. ISBN 978-2-916716-45-9. Archived from the original on February 10, 2018. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- Baert 2008, pp. 03–20.

- Souza 2015, pp. 27–38.

- "Quran". 2015. Archived from the original on May 22, 2015.

- El-Cheikh 1999, p. 7.

- Summary of the plot of the poem Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine at the Swahili Manuscripts Project at the School of Oriental and African Studies of London.

- El-Cheikh 1999, p. 9.

- El-Cheikh 1999, p. 12.

- Conrad 2002, p. 120.

- Haykal 1994, p. 402.

- El-Cheikh 1999, p. 14.

- El-Cheikh 1999, p. 54.

- Lawrence I. Conrad. 'Heraclius in Early Islamic Kerygma' Edited by Reinink and Stolte. (Leuven, Paris: Peeters, 2002)

- Walter Emil Kaegi (March 27, 2003). Heraclius, Emperor of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-521-81459-1. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 229.

- Weitzmann 1979, p. 35-36. See also https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/477154

- Alexander 1977, p. 230.

- Spatharakis 1976, p. 19.

- Bellinger-Grierson 1992, p. 385.

- Kaegi 2003, p. 120.

- Charanis 1959, p. 34.

- Sebeos; Translated from Old Armenian by Robert Bedrosian. "Chapter 29". Sebeos History: A History of Heraclius. History Workshop. Archived from the original on December 9, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- Nicephorus 1990, p. 73.

Sources

- Alexander, Suzanne Spain (April 1977). "Heraclius, Byzantine Imperial Ideology, and the David Plates". Medieval Academy of America. 52 (2): 217–237. JSTOR 2850511.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baert, Barbara (2008). "Héraclius, l'Exaltation de la Croix et le Mont-Saint-Michel au XIe siècle: une lecture attentive du ms. 641 de la Pierpont Morgan Library à New York". Cahiers de Civilisation médiévale (in French) (51): 03–20.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baynes, Norman H. (1912). "The restoration of the Cross at Jerusalem". The English Historical Review. 27 (106): 287–299. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXVII.CVI.287. ISSN 0013-8266.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bellinger, Alfred Raymond; Grierson, Philip. Catalogue of the Byzantine coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and in the Whittemore Collection, Volume 2, Parts 1–2 (1992 ed.). Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 0-88402-024-X.

- Bury, John Bagnell (January 1, 1999). A history of the later Roman empire from Arcadius to Irene (2005 ed.). Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4021-8368-2.

- Cameron, Averil (1979). "Images of Authority: Elites and Icons in Late Sixth-century Byzantium". Past and Present. 84: 3. doi:10.1093/past/84.1.3.

- Charles, Robert H. (2007) [1916]. The Chronicle of John, Bishop of Nikiu: Translated from Zotenberg's Ethiopic Text. Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 9781889758879.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charanis, Peter (1959). "Ethnic Changes in the Byzantine Empire in the Seventh Century". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Trustees for Harvard University. 13 (1): 23–44. doi:10.2307/1291127. ISSN 0070-7546. JSTOR 1291127.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Roger (May 21, 2004). Visigothic Spain, 409–711 (2004 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-18185-7.

- Conrad, Lawrence I (2002). Heraclius in early Islamic Kerygma In "The reign of Heraclius (610–641): crisis and confrontation" (2002 ed.). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-1228-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, Leo Donald (1990). The first seven ecumenical councils (325–787): their history and theology (1990 ed.). Liturgical Press. ISBN 0-8146-5616-1.

- Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History (January 1, 1996 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820171-0.

- Deanesly, Margaret. A history of early medieval Europe, 476 to 911 (July 1969 ed.). Methuen young books. ISBN 0-416-29970-9.

- Dodgeon, Michael H.; Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part I, 226–363 AD). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00342-3.

- El-Cheikh, Nadia Maria (1999). "Muḥammad and Heraclius: A Study in Legitimacy". Studia Islamica. Maisonneuve & Larose. 62 (89): 5–21. doi:10.2307/1596083. ISSN 0585-5292. JSTOR 1596083.

- El-Cheikh, Nadia Maria (2004). Byzantium viewed by the Arabs (2004 ed.). Harvard CMES. ISBN 0-932885-30-6.}

- Foss, Clive (1975). "The Persians in Asia Minor and the End of Antiquity". The English Historical Review. 90: 721–47. doi:10.1093/ehr/XC.CCCLVII.721.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Franzius, Enno. "Heraclius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 11, 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frolow, Anatole (1953). La Vraie Croix et les expéditions d'Héraclius en Perse. Revue des études byzantines. pp. 88–105.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibbon, Edward (1994). David Womersley (ed.). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140433937.

- Grabar, André (1984). L'Iconoclasme Byzantin: le Dossier Archéologique (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-081634-9.

- Haykal, Muhammad Husayn (1994). The Life of Muhammad (1994 ed.). The Other Press. ISBN 978-983-9154-17-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaegi, Walter Emil (March 27, 2003). Heraclius: emperor of Byzantium (2003 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81459-6.

- Haldon, John (1997). Byzantium in the Seventh Century: the Transformation of a Culture. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-31917-X.

- Kouymjian, Dickran. "Ethnic Origins and the 'Armenian' Policy of Emperor Heraclius". Revue des Études Arméniennes (vol. XVII, 1983 ed.).

- Lewis, Bernard (March 14, 2002). The Arabs in History (2002 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280310-7.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450-680 A.D. The Church in history. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410556.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milani, Abbas (2004). Lost wisdom: rethinking modernity in Iran (2004 ed.). Mage Publishers. ISBN 0-934211-89-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Stephen (September 18, 2006). A history of the later Roman Empire, AD 284–641: the transformation of the ancient world (2007 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 1-4051-0857-6.

- Nicephorus (1990). Short history. Translated by Cyril Mango (1990 ed.). Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 0-88402-184-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Olster, David Michael. The politics of usurpation in the seventh century: rhetoric and revolution in Byzantium (1993 ed.). A.M. Hakkert.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Souza, Guilherme Queiroz de (2015). "Heraclius, emperor of Byzantium" (PDF). Revista Digital de Iconografía Medieval. 7 (14): 27–38.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spatharakis, Iohannis (1976). The portrait in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts (1976 ed.). Brill Archive. ISBN 90-04-04783-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Speck, Paul (1984). "Ikonoklasmus und die Anfänge der Makedonischen Renaissance". Varia 1 (Poikila Byzantina 4). Rudolf Halbelt. pp. 175–210.

- Tarasov, Oleg (2004). Icon and Devotion: Sacred Spaces in Imperial Russia (January 3, 2004 ed.). Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-118-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Theophanes the Confessor. The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor. Translated by Cyril Mango; Roger Scott (July 10, 1997 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822568-7.

- Thomson, Robert W.; Howard-Johnston, James & Greenwood, Tim (1999). The Armenian history attributed to Sebeos (1999 ed.). Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-564-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Treadgold, Warren (October 1997). A History of Byzantine State and Society (1997 ed.). University of Stanford Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Weitzmann, Kurt (1979). Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century (1979 ed.). Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-179-5.

Further reading

- Kazhdan, Alexander P. The Oxford dictionary of Byzantium, Volumes 1–3 (1991 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Hovorun, Cyril (2008). Will, Action and Freedom: Christological Controversies in the Seventh Century. Leiden-Boston: BRILL. ISBN 978-9004166660.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Heraclius. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heraclius. |

- "Heraclius" at De Imperatoribus Romanis—online encyclopedia of Roman Emperors

Heraclius Heraclian Dynasty Born: ca. 575 Died: 11 February 641 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Phocas |

Byzantine Emperor 610–641 with Constantine III from 613 |

Succeeded by Constantine III and Heraklonas |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Imp. Caesar Flavius Phocas Augustus, 603, then lapsed |

Consul of the Roman Empire 608 with Heraclius the Elder |

Succeeded by Lapsed, then Imp. Caesar Constantinus Augustus in 642 |