Magister militum

Magister militum (Latin for "Master of the Soldiers", plural magistri militum) was a top-level military command used in the later Roman Empire, dating from the reign of Constantine the Great. The term referred to the senior military officer (equivalent to a war theatre commander, the emperor remaining the supreme commander) of the Empire. In Greek sources, the term is translated either as strategos or as stratelates.

Establishment and development of the Command

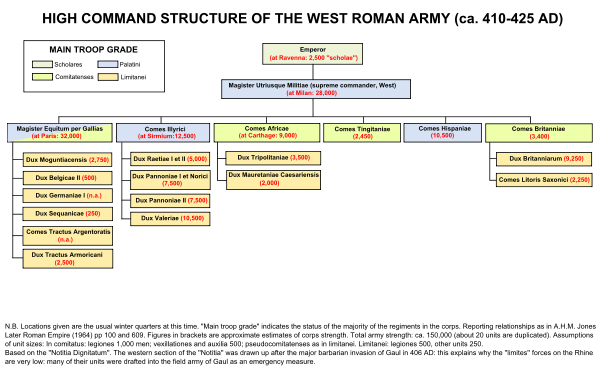

The title of magister militum was created in the 4th century, when Emperor Constantine the Great deprived the praetorian prefects of their military functions. Initially two posts were created, one as head of the foot troops, as the magister peditum ("Master of the Infantry"), and one for the more prestigious horse troops, the magister equitum ("Master of the Cavalry"). The latter title had existed since Republican times, as the second-in-command to a Roman dictator.

Under Constantine's successors, the title was also established at a territorial level: magistri peditum and magistri equitum were appointed for every praetorian prefecture (per Gallias, per Italiam, per Illyricum, per Orientem), and, in addition, for Thrace and, sometimes, Africa. On occasion, the offices would be combined under a single person, then styled magister equitum et peditum or magister utriusque militiae ("master of both forces").

As such they were directly in command of the local mobile field army of the comitatenses, composed mostly of cavalry, which acted as a rapid reaction force. Other magistri remained at the immediate disposal of the Emperors, and were termed in praesenti ("in the presence" of the Emperor). By the late 4th century, the regional commanders were termed simply magister militum.

In the Western Roman Empire, a "commander-in-chief" evolved with the title of magister utriusque militiae. This powerful office was often the power behind the throne and was held by Stilicho, Flavius Aetius, Ricimer, and others. In the East, there were two senior generals, who were each appointed to the office of magister militum praesentalis.

During the reign of Emperor Justinian I, with increasing military threats and the expansion of the Eastern Empire, three new posts were created: the magister militum per Armeniam in the Armenian and Caucasian provinces, formerly part of the jurisdiction of the magister militum per Orientem, the magister militum per Africam in the reconquered African provinces (534), with a subordinate magister peditum, and the magister militum Spaniae (ca. 562).

In the course of the 6th century, internal and external crises in the provinces often necessitated the temporary union of the supreme regional civil authority with the office of the magister militum. In the establishment of the exarchates of Ravenna and Carthage in 584, this practice found its first permanent expression. Indeed, after the loss of the eastern provinces to the Muslim conquest in the 640s, the surviving field armies and their commanders formed the first themata.

Supreme military commanders sometimes also took this title in early medieval Italy, for example in the Papal States and in Venice, whose Doge claimed to be the successor to the Exarch of Ravenna.

List of magistri militum

| |

| Part of a series on the | |

| Military of ancient Rome | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| |

Unspecified commands

- 383-385/8: Flavius Bauto, magister militum under Valentinian II[1]

- 385/8-394: Arbogast, magister militum under Valentinian II and Eugenius[1]

- 383–388: Andragathius[2]

- after 383-408: Flavius Stilicho

- 422-?: Asterius[3][4]

- ? – 480: Ovida

Comes et Magister Utriusque Militiae

- 411 – 421: Flavius Constantius [5]

- 422 - 425: Castinus

- 425 - 430: Flavius Constantius Felix [6]

- 431 - 432: Bonifacius [7]

- 432 - 433: Sebastianus

- 433 – 454: Flavius Aetius[8]

- 455 - 456: Avitus & Remistus

- 456 – 472: Ricimer

- 472–473: Gundobad

- 475: Ecdicius Avitus

- 475–476: Flavius Orestes

per Gallias

- 352–355: Claudius Silvanus

- 362–364: Flavius Valerius Jovinus, magister equitum under Julian and Jovian[9]

- ? – 419: Flavius Gaudentius

- 425–430: Flavius Aetius

- 435-439: Litorius

- 452–458: Agrippinus

- 458–461: Aegidius

- 461/462: Agrippinus

- ? - 472: Bilimer

per Illyricum

- ?-350: Vetranio, magister peditum under Constans[13]

- 361: Flavius Iovinus, magister equitum under Julian[9]

- 365–375: Aequitius, magister utriusquae militiae under Valentinian I[14]

- 395-? Alaric I

- 448/9 Agintheus (known from Priscus of Panium to have held office as the latter's embassy proceeded towards the court of Attila).

- 468–474: Julius Nepos

- 477–479: Onoulphus

- 479–481: Sabinianus Magnus

- 528: Ascum

- 529–530/1: Mundus (1st time)

- 532–536: Mundus (2nd time)

- c. 538: Justin

- c. 544: Vitalius

- c. 550: John

- 568–569/70: Bonus

- 581–582: Theognis

per Orientem

- c. 347: Flavius Eusebius, magister utriusquae militiae[15]

- 349–359: Ursicinus, magister equitum under Constantius[13]

- 359–360: Sabinianus, magister equitum under Constantius[13]

- 363–367: Lupicinus, magister equitum under Jovian and Valens[9]

- 371–378: Iulius, magister equitum et Peditum under Valens[9]

- 383: Flavius Richomeres, magister equitum et peditum[1]

- 383–388: Ellebichus, magister equitum et peditum[1]

- 392: Eutherius, magister equitum et peditum[1]

- 393–396: Addaeus, magister equitum et peditum[1]

- 395/400: Fravitta

- 433–446: Anatolius

- 447–451: Zeno

- 460s: Flavius Ardabur Aspar

- -469: Flavius Iordanes

- 469–471: Zeno

- 483–498: Ioannes Scytha

- c. 503–505: Areobindus Dagalaiphus Areobindus

- 505–506: Pharesmanes

- ?516-?518: Hypatius

- ?518–529: Diogenianus

- 520-525/526: Hypatius

- 527: Libelarius

- 527–529: Hypatius

- 529–531: Belisarius

- 531: Mundus

- 532–533: Belisarius

- 540: Buzes

- 542: Belisarius

- 543–544: Martinus

- 549–551: Belisarius

- 555: Amantius

- 556: Valerianus

- 569: Zemarchus

- 572–573: Marcian

- 573: Theodorus

- 574: Eusebius

- 574/574-577: Justinian

- 577–582: Maurice

- 582–583: John Mystacon

- 584-587/588: Philippicus

- 588: Priscus

- 588–589: Philippicus

- 589–591: Comentiolus

- 591–603: Narses

- 603-604 Germanus

- 604-605 Leontius

- 605-610 Domentziolus

per Armeniam

- Peter, direct predecessor of John Tzibus

- John Tzibus (?-541)

- Valerian

- Dagisthaeus (?-550)

- Bessas (550-554)[16]

- Martin[17]

- Justin[18]

- Heraclius the Elder (ca. 595)[19]

per Thracias

- 377–378: Flavius Saturninus, magister equitum under Valens[9]

- 377–378: Traianus, magister peditum under Valens[1]

- 378: Sebastianus, magister peditum under Valens[1]

- 380–383: Flavius Saturninus, magister peditum under Theodosius I[1]

- 392–393: Flavius Stilicho, magister equitum et peditum[1]

- 412–414: Constans

- 441: Ioannes the Vandal, magister utriusque militiae[20]

- 468–474: Armatus

- 474: Heraclius of Edessa

- 511: Hypatius

- 512: Cyril

- 514: Vitalian

- 530–533: Chilbudius

- 550–ca. 554: Artabanes

- 588: Priscus (1st time)

- 593: Priscus (2nd time)

- 593–594: Peter (1st time)

- 594–ca. 598: Priscus (2nd time)

- 598–601: Comentiolus

- 601–602: Peter (2nd time)

Praesentalis

- 351–361: Flavius Arbitio, magister equitum under Constantius[13]

- 361–363: Flavius Nevitta, magister equitum under Julian[9]

- 363–379: Victor, magister equitum under Valens[9]

- 366–378: Flavius Arinthaeus, magister peditum under Valens[9]

- 364–369: Flavius Iovinus, magister equitum under Valentinian I[9]

- 364–366: Dagalaifus, magister peditum under Valentinian I[9]

- 367–372: Severus, magister peditum under Valentinian I[9]

- 369–373: Flavius Theodosius, magister equitum under Valentinian I[9]

- 375–388: Merobaudes, magister peditum under Valentinian I, Gratian and Magnus Maximus[21]

- 388-395: Timasius

- 394–408: Flavius Stilicho, magister equitum et peditum[1]

- 399-400: Gainas

- 400: Fravitta

- 409: Varanes and Arsacius[22]

- 419-: Plinta

- 434–449: Areobindus?

- 443–451: Apollonius

- 450–451: Anatolius

- 475-477/478: Armatus

- 485–: Longinus

- 492–499: John the Hunchback

- 518–520: Vitalian [23]

- 520–?: Justinian [24]

- 528: Leontius

- 528-529: Phocas

- 520-538/9: Sittas

- 536: Germanus

- 536: Maxentianus

- 546–548: Artabanes

- 548/9–552: Suartuas

- 562: Constantinianus (uncertain)

- 582: Germanus (uncertain)

- 585–ca. 586: Comentiolus

- 626: Bonus (uncertain)

per Africam

Eastern Empire

- 534–536: Solomon

- 536–539: Germanus

- 539–544: Solomon

- 544–546: Sergius

- 545–546: Areobindus

- 546: Artabanes

- 546–552: John Troglita

- 578–590: Gennadius

Magister Militae in Byzantine and medieval Italy

Venice

- 8th century: Marcellus

- 737: Domenico Leoni under Leo III the Isaurian

- 738: Felice Cornicola under Leo III the Isaurian

- 739: Theodatus Hypatus under Leo III the Isaurian

- 741: Ioannes Fabriacius under Leo III the Isaurian

- 764–787: Mauricius Galba

Later, less formal use of the term

By the 12th century, the term was being used to describe a man who organized the military force of a political or feudal leader on his behalf. In the Gesta Herwardi, the hero is several times described as magister militum by the man who translated the original Early English account into Latin. It seems possible that the writer of the original version, now lost, thought of him as the 'hereward' – the supervisor of the military force. That this later use of these terms was based on the classical concept seems clear.[26]

References

Citations

- PLRE I, p. 1114

- PLRE I, p. 62

- Arce (2004), Bárbaros y romanos en Hispania, 400-507 A.D, pág. 112

- Gil, M.E. (2000), Barbari ad Pacem Incundam Conversi. El Año 411 en Hispania, pág. 83

- Hughes, Ian: Aetius: Attila's Nemesis, pg. 74

- Hughes, Ian: Aetius: Attila's Nemesis, pg. 75

- Hughes, Ian: Aetius: Attila's Nemesis, pg. 85

- Hughes, Ian: Aetius: Attila's Nemesis, pg. 87, Heather, Peter: The Fall of the Roman Empire, pg. 262, 491

- PLRE I, p. 1113

- Hydatius, Chronica Hispania, 122

- Hydatius, Chronica Hispania, 128

- Hydatius, Chronica Hispania, 134

- PLRE I, p. 1112

- PLRE I, p. 125

- PLRE I, p. 307

- Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Martindale, J. R.; Morris, J. (1980). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume 2, AD 395-527. Cambridge University Press. p. 228. ISBN 9780521201599.

- Martindale, J. R. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire 2 Part Set: Volume 3, AD 527-641. Cambridge University Press. p. 845. ISBN 978-0-521-20160-5.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2005). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars AD 363-628. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-75645-2.

- Kaegi, Walter Emil (2003). Heraclius, Emperor of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780521814591.

- PLRE II, p. 597

- PLRE I, pp. 1113–1114

- PLRE I, p. 152

- John Moorhead, Justinian (London, 1994), p. 16.

- John Moorhead, Justinian (London, 1994), p. 17.

- PLRE I, p. 395

- Gesta Herwardi Archived 2011-01-21 at the Wayback Machine The term is used in chapters XII, XIV, XXII and XXIII. See The Name, Hereward for details.

Sources

- Works cited

- Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire (PLRE), Vols. I-III