Chi Rho

The Chi Rho (/ˈkaɪ ˈroʊ/; also known as chrismon[1]) is one of the earliest forms of christogram, formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters—chi and rho (ΧΡ)—of the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Christos) in such a way that the vertical stroke of the rho intersects the center of the chi.[2]

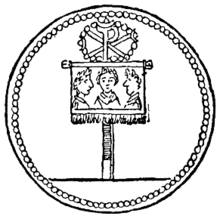

The Chi-Rho symbol was used by the Roman Emperor Constantine I (r. 306–337) as part of a military standard (vexillum). Constantine's standard was known as the Labarum. Early symbols similar to the Chi Rho were the Staurogram (![]()

![]()

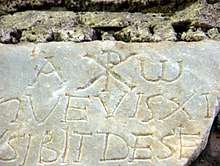

In pre-Christian times, the Chi-Rho symbol was also to mark a particularly valuable or relevant passage in the margin of a page, abbreviating chrēston (good).[3] Some coins of Ptolemy III Euergetes (r. 246–222 BC) were marked with a Chi-Rho.[4]

Although formed of Greek characters, the device (or its separate parts) is frequently found serving as an abbreviation in Latin text, with endings added appropriate to a Latin noun, thus XPo, signifying Christo, "to Christ", the dative form of Christus.[5]

The Chi Rho symbol has two Unicode codepoints: U+2627 ☧ CHI RHO in the Miscellaneous symbols block and U+2CE9 ⳩ COPTIC SYMBOL KHI RO in the Coptic block.

Origin and adoption

According to Lactantius,[6] a Latin historian of North African origins saved from poverty by the Emperor Constantine the Great (r. 306–337), who made him tutor to his son Crispus, Constantine had dreamt of being ordered to put a "heavenly divine symbol" (Latin: coeleste signum dei) on the shields of his soldiers. The description of the actual symbol chosen by Emperor Constantine the next morning, as reported by Lactantius, is not very clear: it closely resembles a Tau-Rho or a staurogram (![]()

Eusebius of Caesarea (died in 339) gave two different accounts of the events. In his church history, written shortly after the battle, when Eusebius hadn't yet had contact with Constantine, he doesn't mention any dream or vision, but compares the defeat of Maxentius (drowned in the Tiber) to that of the biblical pharaoh and credits Constantine's victory to divine protection.

In a memoir of the Roman emperor that Eusebius wrote after Constantine's death (On the Life of Constantine, circa 337–339), a miraculous appearance is said to have come in Gaul long before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. In this later version, the Roman emperor had been pondering the misfortunes that befell commanders who invoked the help of many different gods, and decided to seek divine aid in the forthcoming battle from the One God. At noon, Constantine saw a cross of light imposed over the sun. Attached to it, in Greek characters, was the saying "Τούτῳ Νίκα!" (“In this sign you will conquer!”).[7] Not only Constantine, but the whole army saw the miracle. That night, Christ appeared to the Roman emperor in a dream and told him to make a replica of the sign he had seen in the sky, which would be a sure defence in battle.

Eusebius wrote in the Vita that Constantine himself had told him this story "and confirmed it with oaths" late in life "when I was deemed worthy of his acquaintance and company." "Indeed", says Eusebius, "had anyone else told this story, it would not have been easy to accept it."

Eusebius also left a description of the labarum, the military standard which incorporated the Chi-Rho sign, used by Emperor Constantine in his later wars against Licinius.[8]

Later usage

Late antiquity

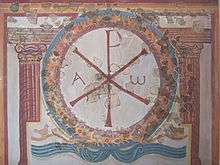

An early visual representation of the connection between the Crucifixion of Jesus and his resurrection, seen in the 4th century sarcophagus of Domitilla in Rome, the use of a wreath around the Chi-Rho symbolizes the victory of the Resurrection over death.[11]

After Constantine, the Chi-Rho became part of the official imperial insignia. Archaeologists have uncovered evidence demonstrating that the Chi-Rho was emblazoned on the helmets of some Late Roman soldiers. Coins and medallions minted during Emperor Constantine's reign also bore the Chi-Rho. By the year 350, the Chi-Rho began to be used on Christian sarcophagi and frescoes. The usurper Magnentius appears to have been the first to use the Chi-Rho monogram flanked by Alpha and Omega, on the reverse of some coins minted in 353.[12] In Roman Britannia, a tesselated mosaic pavement was uncovered at Hinton St. Mary, Dorset, in 1963. On stylistic grounds, it is dated to the 4th century; its central roundel represents a beardless male head and bust draped in a pallium in front of the Chi-Rho symbol, flanked by pomegranates, symbols of eternal life. Another Romano-British Chi-Rho, in fresco, was found at the site of a villa at Lullingstone (illustrated). The symbol was also found on Late Roman Christian signet rings in Britain.[13]

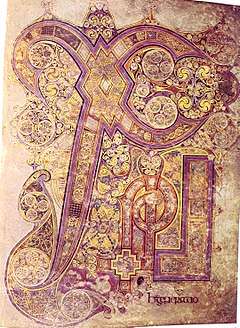

Insular Gospel books

In Insular Gospel books, the beginning of Matthew 1:18, at the end of his account of the genealogy of Christ and introducing his account of the life, so representing the moment of the Incarnation of Christ, was usually marked with a heavily decorated page, where the letters of the first word "Christi" are abbreviated and written in Greek as "XPI", and often almost submerged by decoration.[14] Though the letters are written one after the other and the "X" and "P" not combined in a monogram, these are known as Chi-Rho pages.

Famous examples are in the Book of Kells and Book of Lindisfarne.[15] The "X" was regarded as the crux decussata, a symbol of the cross; this idea is found in the works of Isidore of Seville and other patristic and Early Medieval writers.[16] The Book of Kells has a second Chi-Rho abbreviation on folio 124 in the account of the Crucifixion of Christ,[17] and in some manuscripts the Chi-Rho occurs at the beginning of Matthew rather than mid-text at Matthew 1:18. In some other works like the Carolingian Godescalc Evangelistary, "XPS" in sequential letters, representing "Christus" is given a prominent place.[18]

Gallery

The Chi-Rho symbol ☧, Catacombs of San Callisto, Rome.

The Chi-Rho symbol ☧, Catacombs of San Callisto, Rome. Monogramme of Christ (the Chi Rho) on a plaque of a sarcophagus, 4th-century CE, marble, Musei Vaticani, on display in a temporary exhibition at the Colosseum in Rome, Italy

Monogramme of Christ (the Chi Rho) on a plaque of a sarcophagus, 4th-century CE, marble, Musei Vaticani, on display in a temporary exhibition at the Colosseum in Rome, Italy The Chi-Rho symbol ☧, Catacombs of Domitilla, Rome.

The Chi-Rho symbol ☧, Catacombs of Domitilla, Rome. The Chi-Rho symbol ☧ with Alpha and Omega, Catacombs of Domitilla, Rome.

The Chi-Rho symbol ☧ with Alpha and Omega, Catacombs of Domitilla, Rome. Constantinople Christian sarcophagus with XI monogram, circa 400.

Constantinople Christian sarcophagus with XI monogram, circa 400. The Chi-Rho with a wreath symbolizing the victory of the Resurrection, above Roman soldiers, circa 350.

The Chi-Rho with a wreath symbolizing the victory of the Resurrection, above Roman soldiers, circa 350. Chi-Rho on a 4th-century altar, Khirbet Um El’Amad, Algeria.

Chi-Rho on a 4th-century altar, Khirbet Um El’Amad, Algeria. Roman Chi Rho applique in bronze from a Germanic settlement in Neerharen (Belgium), 375-450 CE, Gallo-Roman Museum (Tongeren)

Roman Chi Rho applique in bronze from a Germanic settlement in Neerharen (Belgium), 375-450 CE, Gallo-Roman Museum (Tongeren) Silver ring with Chi Rho symbol found at a Christian burial site in Late Roman Tongeren (Belgium), 4th century CE, Gallo-Roman Museum (Tongeren)

Silver ring with Chi Rho symbol found at a Christian burial site in Late Roman Tongeren (Belgium), 4th century CE, Gallo-Roman Museum (Tongeren)- Christian pendant of Maria (398–407), wife of the Emperor Honorius (r. 395–423), with text in the shape of a Chi-Rho, Louvre.

Roman Christian mosaic with Chi-Rho, Hinton St. Mary, England.

Roman Christian mosaic with Chi-Rho, Hinton St. Mary, England.

Reconstruction of Chi-Rho fresco from Roman villa at Lullingstone, including Alpha and Omega.

Reconstruction of Chi-Rho fresco from Roman villa at Lullingstone, including Alpha and Omega. Sarcophagus with Chi-Rho symbol and Alpha and Omega, 6th century, Soissons, France

Sarcophagus with Chi-Rho symbol and Alpha and Omega, 6th century, Soissons, France Folio 34r of the Book of Kells is the Chi Rho page, expanding the first two letters of the word Christ.

Folio 34r of the Book of Kells is the Chi Rho page, expanding the first two letters of the word Christ. Sequential "XPS" in the Carolingian Godescalc Evangelistary.

Sequential "XPS" in the Carolingian Godescalc Evangelistary. Chi-Rho on the roof of the Basilica of St. John Lateran, Rome.

Chi-Rho on the roof of the Basilica of St. John Lateran, Rome. Chi-Rho and Alpha and Omega on a modern Catholic altar.

Chi-Rho and Alpha and Omega on a modern Catholic altar. Chi-Rho on YMCA building, Over-the-Rhine, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Chi-Rho on YMCA building, Over-the-Rhine, Cincinnati, Ohio.

See also

References

Notes

- From a supposed Middle Latin crismon), specifically applied to the "Chrismon of Saint Ambrose" in Milan Cathedral. Crismon (par les Bénédictins de St. Maur, 1733–1736), in: du Cange, et al., Glossarium mediae et infimae latinitatis, ed. augm., Niort: L. Favre, 1883‑1887, t. 2, col. 621b. "CRISMON, Nota quæ in libro ex voluntate uniuscujusque ad aliquid notandum ponitur. Papias in MS. Bituric. Crismon vel Chrismon proprie est Monogramma Christi sic expressum ☧"; 1 chrismon (par les Bénédictins de St. Maur, 1733–1736), in: du Cange, et al., Glossarium mediae et infimae latinitatis, ed. augm., Niort : L. Favre, 1883‑1887, t. 2, col. 318c.

- Steffler 2002, p. 66.

- Southern 2001, p. 281; Grant 1998, p. 142, citing Bruun, Studies in Constantinian Numismatics.

- von Reden 2007, p. 69: "The chi-rho series of Euergetes' reign had been the most extensive series of bronze coins ever minted, comprising eight denominations from 1 chalkous to 4 obols."

- For example as inscribed on the monumental brass of Thomas de Camoys, 1st Baron Camoys (d.1421) in St George's Church, Trotton, Sussex, England

- Lactantius. On the Deaths of the Persecutors, Chapter 44.

- The well known sentence In hoc signo vinces is simply a later Latin translation of Eusebius's Greek wording.

- Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine, Chapter 31.

- Kenelm Henry Digby, Mores Catholici, Or, Ages of Faith vol. 1 (1844), p. 300.

- A. L. Millin, Voyage dans le Milanais (1817), p. 51.

- Harries 2004, p. 8. Sarcophagus with Scenes of the Passion (probably from the Catacomb of Domitilla), Rome, mid-fourth century. Marble, 23ʺ x 80ʺ. Museo Pio Christiano, Vatican, Rome.

- Kellner 1968, p. 57ff. See also Grigg 1977, p. 469 (Note #4).

- Johns 1996, p. 67.

- In the Latin Vulgate the verse was "Christi autem generatio sic erat cum esset desponsata mater eius Maria Ioseph antequam convenirent inventa est in utero habens de Spiritu Sancto" ("Now the birth of Jesus Christ took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been betrothed to Joseph, before they came together she was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit")

- Lewis 1980, pp. 142–143.

- Lewis 1980, pp. 143–144.

- Lewis 1980, p. 144.

- Lewis 1980, p. 153.

Bibliography

- Grant, Michael (1998). The Emperor Constantine. London, United Kingdom: Phoenix Giant. ISBN 0-7538-0528-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grigg, Robert (December 1977). ""Symphōnian Aeidō tēs Basileias": An Image of Imperial Harmony on the Base of the Column of Arcadius". The Art Bulletin. 59 (4): 469–482. doi:10.2307/3049702. JSTOR 3049702.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harries, Richard (2004). The Passion in Art. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7546-5011-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johns, Catherine (1996). The Jewellery of Roman Britain: Celtic and classical Traditions. Oxon, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group). ISBN 1-85728-566-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kellner, Wendelin (1968). Libertas und Christogramm: Motivgeschichtliche Untersuchungen zur Münzprägung des Kaisers Magnentius (350-353) (in German). Karlsruhe, Germany: Verlag G. Braun.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Suzanne (1980). "Sacred Calligraphy: The Chi Rho Page in the Book of Kells". Traditio. Cambridge University Press. 36: 139–159. doi:10.1017/S0362152900009235. JSTOR 27831075.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Southern, Pat (2001). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group). ISBN 0-415-23943-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steffler, Alva William (2002). Symbols of the Christian Faith. Grand Rapids, Michigan and Cambridge, United Kingdom: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-4676-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- von Reden, Sitta (2007). Money in Ptolemaic Egypt: From the Macedonian Conquest to the End of the Third Century BC. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85264-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Heiland, Fritz (1948). "Die astronomische Deutung der Vision Kaiser Konstantins". Sondervortrag Im Zeiss-Planatarium-Jena: 11–19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Latura, George (2012). "Plato's Visible God: The Cosmic Soul Reflected in the Heavens". Religions. 3 (3): 880–886. doi:10.3390/rel3030880.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rahner, Hugo; Battershaw, Brian (translator) (1971). Greek Myths and Christian Mystery. New York, New York: Biblo & Tannen Booksellers and Publishers Incorporated. ISBN 0-8196-0270-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "Constantine Triumphed under Sign of Cross". christianity.com.