German and Sarmatian campaigns of Constantine

The German and Sarmatian campaigns of Constantine were fought by the Roman Emperor Constantine I against the neighbouring Germanic peoples, including the Franks, Alemanni and Goths, as well as the Sarmatian Iazyges, along the whole Roman northern defensive system to protect the empire's borders, between 306 and 336.

| German and Sarmatian campaigns of Constantine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Germanic Wars | |||||||

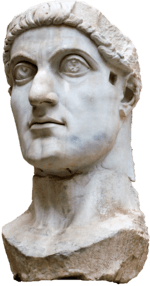

Emperor Constantine I | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Germanic and Sarmatian peoples | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Rausimodus | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Numerous legions | Many people, amounting to some hundreds of thousands of armed | ||||||

After becoming controller of the western provinces along the Rhine limes (in 306) following the death of his father Constantius Chlorus (Augustus of the west) in 306, Constantine initially concentrated his forces on defending this area of the frontier against the Franks and Alemanni, making Augusta Treverorum his first capital for this purpose. Having defeated the usurper Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312,[2] all Italia passed under Constantine's control and he thus became the sole Augustus of the West.

In February 313, Constantine (who had spent the winter in Rome) formed an alliance with the Emperor of the East, Licinius, reinforced by Licinius' marriage to Constantine's sister, Flavia Julia Constantia.[3] However, this alliance survived for only a few years, before the two Augusti came into conflict in 316. Constantine defeated Licinius, who was forced to cede Illyricum to Constantine,[4] but not Thrace.[4] Constantine advanced ever further east with his territorial acquisitions, now having to defend the important strategic region of the limes sarmaticus (from 317).

In the following years, Constantine mostly occupied himself in the central section of the Danubian Limes, mostly fighting against the Sarmatians in Pannonia,[5] residing at Sirmium almost continuously until 324 (when he moved against Licinius once more), making it his capital[6] along with Serdica.[7] At this time Constantine also demonstrated a very active military bent, travelling along the whole of the limites of his newly acquired territory. From 320 he appointed his eldest son, Crispus, Praetorian prefect, with military command of Gaul.

When he learnt that an army of Goths[8] had crossed the Danube to raid Roman territory in Moesia Inferior and Thrace, which belonged to Emperor Licinius,[9] he left his general headquarters in Thessalonica[10] and marched against them (323). The fact that he had trespassed into a part of the empire which was not under his control unleashed the final phase of the Civil wars of the Tetrarchy, which ended with the complete defeat of Licinius and the consecration of Constantine as the sole Roman Emperor.[11]

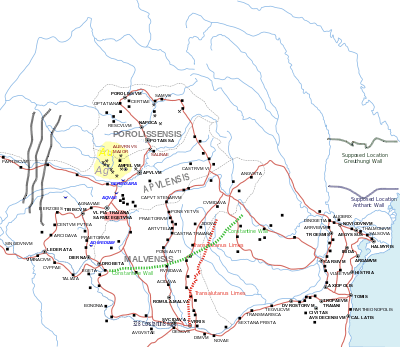

The final period of Constantine's reign, until his death (337), saw the Christian Emperor consolidate the entire defensive system on the Rhine and Danube, obtaining important military successes and reasserting control over a large part of the territory that the Romans had abandoned under Gallienus and Aurelian: the Agri Decumates from the Alemanni, the area south of the Tisza from the Sarmatians, as well as Oltenia and Wallachia from the Goths.

Historical context

With the death of Emperor Numerian in November 284 (who had been entrusted with Eastern Roman empire by his father Carus) and the refusal of the eastern troops to recognise Carus' eldest son Carinus as his successor, a proven general of Illyrian origins, Diocletian, was raised to the purple. At the end of the civil war which followed, Diocletian was victorious and in 285 he named Maximian as his deputy (or Caesar) and then a few months later elevated him to the rank of Augustus (1 April 286), thereby forming a diarchy, in which two emperors divided the government of the empire on geographic lines. This also entailed the division of responsibility for the defence of the northern frontier from Germanic and Sarmatian incursions.[12][13]

Given the increasing difficulty of containing the internal revolts and those along the borders, a further territorial division was executed in 293 to facilitate military operations: Diocletian named Galerius as his Caesar in the east, while Maximian chose Constantius Chlorus in the west.[14]

However, this tetrarchy fell into crisis only a year after the abdication of the two Augusti in 305, beginning a new Civil War (306–324), permitting new breaches along the Roman external border, with populations attempting to settle within Roman territory.

It was only with Constantine's accession to the throne, becoming sole Augustus of the West after the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 and later still defeating Licinius and reuniting the Empire under a single emperor (324) that the northern frontiers were adequately defended once more. It is no coincidence that Constantine is attributed the responsibility for perfecting the military reforms of Diocletian and also for the reconquest or vassalisation of all the territory which Trajan had controlled.[1]

Background: the death of Constantius Chlorus

With the death of Constantius Chlorus at Eboracum (York) on 25 July 306,[15][16] the Tetrarchy entered a crisis: the eldest son of the dead emperor, Constantine was proclaimed Augustus[17] by the Alemanni general Chrocus and the army of Britannia.[18][19][20][21] His election was in accordance with a dynastic principle rather than the meritocratic system of the Tetrarchy created by Diocletian. Only Lactantius maintains that Constantine was named Augustus by his father on his deathbed.[22] Galerius was displeased by this act and offered the son of his deceased colleague the title of Caesar, which Constantine accepted, allowing Flavius Severus to succeed his father Constantius instead.[23] A few months later, Maxentius son of the old Augustus Maximian was acclaimed Emperor by the Praetorian guard with the support of officials like Marcellianus, Marcellus and Lucianus (but not Abellius, vicar of the Praefectus urbi, who was killed), reaffirming the dynastic principle. It was in this period that Constantine began to achieve important military successes against the Alemanni and the Franks, along the stretch of the frontier attributed to him, as is recounted by Eutropius.[24]

Forces in the field

Romans

Regarding the Roman forces garrisoned along the whole stretch of the northern limites from Britannia to Moesia, it is important to note that at this time there was a very important reform of the Roman army, a new Deployment of the Roman legions along the borders and an increase in the size of the Roman army. In fact, we know that, with Diocletian's Tetrarchy reforms, the total number of legions was brought to 55 or 56 in the year 300.[25] Constantine's accession to the throne and the return of a dynastic monarchy brought about the final increase of the number of Roman legions to 62 or 64 around the year 330.[26]

Barbarians

Along the Rhine limes the Franks and Saxons in particular pressed on Gaul and Britannia. The Alemanni also made some incursions in these regions, but the main goal of their attacks at this time was Northern Italy via Pannonia (the western part of the Danubian Limes). The major clashes occurred along the Lower Danube in the Roman provinces of the Balkan region, where the Marcomanni, Quadi, Sarmatians and especially the Goths (divided into the Tervingi and the Greutungi) concentrated their attacks.

Phases of the conflict

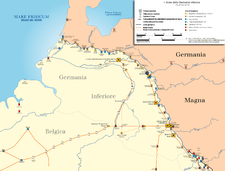

First phase (306–316): defence of the Rhine limes

- 306

- The twenty-one-year-old Constantine, unable to get permission to visit his ailing father Constantius Chlorus (Augustus of the west) from the Augustus of the East, Galerius, in whose court he had lived since the time of Diocletian, decided to escape in the spring of this year. He found his father at Gesoriacum (Boulogne-sur-Mer) about to cross the English Channel to Britannia and joined him in a successful military campaign against the Picts and Scotti to the north of Hadrian's wall.[27] When his father died during the summer, Constantine was proclaimed Augustus of the West by his father's loyal troops at Eboracum on 25 July.

- The young tetrarch however needed his election to the Imperial office to be recognised, particularly by Galerius, the most senior of the Augusti. Gelerius preferred his friend and comrade in arms, Licinius, to Constantine. Confronted with a fait accompli and in the face of the "secession" of Gaul and Britannia, Galerius appealed to precedent and named the former Caesar, Flavius Severus as the new Augustus with control over Italy, Africa, and Spain and recognised Constantine only as a Caesar.[28] Constantine voluntarily accepted this and in Autumn of the same year he returned to Augusta Treverorum (Trier) whence he could more easily monitor the Gallic frontier, which was being menaced by the Franks. He continued to defend this important stretch of the limes for the next six years, transferring his whole imperial court to Trier and transforming it into his capital (with c.80,000 inhabitants), constructing the imposing Aula Palatina in 310.[29] During these years, not only did he reinforce the defences of this region against the continued incursions of the barbarians, but he also strengthened the forces under his control,[30] augmenting his forces through the creation of new legions.

| Constantine I: Follis[31] | |

|---|---|

| |

| IMP CONSTANTINVS P F AVG, laureated head looking right with armoured bust; | MARTI PATRI PROPVGNATORI (with Father Mars, the protector), Mars looking to the right and holding a lance and a shield in his hands; T F on the sides and P TR in the exergue. |

| 25 mm, 6.52 g, minted in 307/308, celebrating the first successes against the Germans in Gaul. | |

- 307

- At the beginning of spring, Constantine planned a new campaign in German territory. He found it necessary to confront the Franks, Chamavi, Bructeri, Cherusci and Alemanni. The young emperor had been educated in the military training ground of the east by Diocletian and Galerius and, despite his youth, conducted the war with the sort of determination and energy which his father had not been able to muster in the preceding years.[32] In the course of the military operations, he achieved important successes, managing to heavily wallop the Franks who had invaded the Roman territory east of the Rhine the previous year.[33][34][35] It is reported that, while the Franks were planning to cross the Lower Rhine, Constantine quickly crossed the river in another location and surprised the enemy with an unexpected attack, which prevented a new invasion. Many of the Franks were killed, captured or enslaved – some of these were employed as gladiators. All their livestock was seized and their villages were burnt to the ground.[36][37] As a result of these successes, Constantine was awarded the cognomen Germanicus Maximus at the end of the year.[37][38][39] In the course of this campaign and those following it, Constantine may have used the legionary fortress of Castra Vetera as a base and the valley of the Lippe (as had been done in the time of Augustus and again fifty years later under Julian[40]) as an invasion route by which to outflank the enemy, who were found to the north of this major river, and catch them from behind after devastating their territory.

| Constantine I: Follis[41] | |

|---|---|

| |

| IMP CONSTANTINVS P F AVG, laureate head facing right with armoured bust covered in drapery; | MARTI PATRI CONSERVATORI (with Father Mars the conservator), Mars on his feet, turning to the right, holding a lance and a shield in his hands, S A on the sides and P TR underneath. |

| 26 mm, 6.72 g, minted in 307/308, celebrating the first successes over the Germans in Gaul and the successful defence of the limes.. | |

- 308

- Further successes were achieved by Constantine against the Bructeri over the whole year, for which he received the title of Germanicus Maximus once again.[37][38][42]

At the end of this new military campaign against the Franks, Constantine built the important "bridgehead" of Divitia (modern Deutz) in German territory opposite Colonia Agrippina (Cologne).[43]

- 310

- Once more Constantine achieved important military successes over the Alemanni and the Franks, whose king he is said to have captured and fed to the beasts in the amphitheatre.[24][44] In the course of this campaign against the Franks, Constantine added a majestic bridge at Divitia, 420 metres long and 10 metres wide.[45][46]

Meanwhile, however, Maximian had rebelled and Constantine had to cut his campaign against the Franks short, marching rapidly to southern Gaul where he captured Maximian and forced him to commit suicide.[24][47][48][49]

- 311

- With the death of Galerius, the Tetrarchy became ever more unstable. Probably as a result of this, no campaigns against the Germans beyond the Rhine seem to have been undertaken this year. On the contrary, Constantine fortified the Rhine limes ever further with new construction (as at Haus Bürgel on the right bank of the river, 30 km north of Divitia, or along the roads leading from Colonia Agrippina (Cologne) to Augusta Treverorum (Trier)[50]) and with the strengthening of preexisting fortifications. Since the auxiliary fortress of Noviomagus Batavorum (Nijmegen) had, apparently, been abandoned at the end of the third century, Constantine constructed two new forts in the area: at Valkhof (on the banks of the river Waal) and another along the coast at Valkenburg (near Hook).[46]

| Constantine I: aureus[51] | |

|---|---|

| |

| CONSTAN-TINUS PR AVG, laureate head facing right; | GAVDIVM ROMANORUM ("Celebration of the Romans"), Alemannia seated, mourning, below a military trophy; ALEMANNIA in exergue. |

| 4.63 gr, minted in 312/313 to celebrate the successes against the Alemanni. | |

- 312

- Constantine gathered a massive army, including barbarians from the recent wars (Germanic peoples and Celts brought over from Britannia), and led it into Italy, defeating his rival Maxentius at Turin, Verona, and finally at the Milvian Bridge.[2][52] Constantine thus begame sole ruler of the West.[53] The eastern half fell under the control of Licinius the following year, with whom Constantine entered into a marriage alliance.[54]

- 313

- At this time Constantine conducted another military campaign against the Franks and the Alemanni in Gaul, which lasted until the end of summer.[55] Pretending to cross the river, he followed his earlier course, marching against the Alemanni, but then turned back and attacked the Franks with a rapid fleet. He devastated their territories and captured one of their kings. Immediately afterwards he retraced his steps and devastated the territories of the Alemanni as well, a campaign commemorated on the coins of the year, which celebrate the GAVDIVM ROMANORVM ALAMANNIA.[37][44][56][57][58]

- 314–315

- Once again, Constantine made Augusta Treverorum (Trier) his general quarters for these two years, in order to stay more in control of the Rhine frontier, once again putting things in order against possible incursions of Franks and Alemanni and continuing his fortification works.[55] In July of 315 he left the frontier in order to travel to Rome and celebrate his triumph for the Battle of the Milvian Bridge.[59]

- 316–317

- Conflict arose between Licinius and Constantine,[60] who defeated the former at Cibalae[61] and Mardia.[62] In the following peace agreement, Licinius was forced to cede Illyricum to Constantine.[4] Constantine thereby extended his territory to the east and now had another important strategic sector to defend: the limes sarmaticus (or pannonicus), also called the Pannonian Limes, where he had earlier fought in 305, as an official of Galerius, managing to defeat a barbarian general in single combat.[63][64]

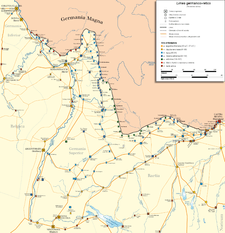

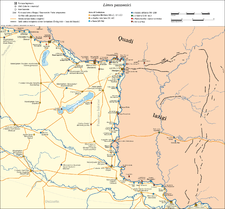

Second phase (317–324): the defence of the limes pannonicus-sarmaticus

| Constantine I: Follis[65] | |

|---|---|

| |

| IMP CONSTAN-TINVS MAX AVG, laureate and helmeted head facing right, with armoured bust; | VICTORIAE LAETAE PRINC PERP ("Joyful victory's eternal prince"), two Victories standing facing each other, holding a shield bearing the inscription VOT/PR on two lines on top of an altar with a *; in exergue P T ("First official of Ticinum]] in esergo. |

| 16 mm, 2.93 gr, minted in 318/319 | |

| Constantine I: Follis[66] | |

|---|---|

| |

| CONST-ANTINVS AVG, laureate and helmeted head facing right, with an armoured bust;; | VIRTUS EXERCIT ("Virtue is practiced"), labarum inscribed VOT/XX in two lines; two bound prisoners facing away from each other; ST (Second official of Ticinum) in the exergue. |

| 19 mm, 3.23 gr, minted in 319/320 | |

- 317–319

- Following the events described above, Constantine fought against the Sarmatians on the Pannonian stretch of the limes, earning the victory title of Sarmaticus Maximus for the first time, as seems to be demonstrated by an inscription found in Mauretania.[5] indicating to Mócsy that he remained as Sirmium almost continuously until 324 (when his armies moved against Licinius), employing it as his capital.[6] Horst too maintains that his preferred imperial residences in the period between 317 and 323 were Serdica and Sirmium.[7]

- During this year, Constantine again showed an active interest in military activities, since he often travelled along the whole limes of the territories he had acquired with the peace of Serdica (March 317). He inspected the garrisons of Pannonia Inferior, overseeing their repair and the construction of new bridgeheads towards the plain of the Tisza River, to face the peril of the barbarians beyond Rome's borders (Iazygi and Goths). He strengthened the river fleets of the Danube, Sava, Drina, and Morava, as well as the maritime fleets of the Adriatic and Aegean Seas, reinforcing the ports of Aquileia, Pireus, and Thessalonica (formerly Galerius' capital) through the construction of arsenals, shipyards, and the construction of further naval squads.[67] Clearly these reconstruction and strengthening works could be employed not only against the barbarians, but also, one day, against Licinius.

- 320

- Constantine's eldest son, Crispus (now fifteen, and therefore aided by a Prefect), received the military command of Gaul and conducted military campaigns along the Rhine, achieving victories over the Franks and Alemanni within the year.[68]

- 322

- Constantine managed to repulse a new invasion of Pannonia by the Sarmatians and the Iazygi.[6][8][37][69][70] After this, Constantine may have begun the construction of a new stretch of border fortifications, the so-called Devil's Dykes,[71] which consisted of a series of north-facing embankments starting by the Danube at Aquincum, heading to the Tisza, then turning south towards the river Mureş, crossing the Banat and reaching the Danube at Viminacium (it is possible that this construction resumed earlier work under Diocletian).[72][73] Accordingly, the coinage of this year and the next declared SARMATIA DEVICTA ("Sarmatia vanquished")[74] and name Constantine as "Sarmaticus Maximus" for the second time.[37]

| Constantine I: Follis[75] | |

|---|---|

| |

| CONSTAN-TINVS AG, laureate head facing right; | SARMATIA DEVICTA (Sarmatia vanquished), Victory facing, holds a trophy and a palm, with a prisoner seated at her feet; in the exergue P LON. |

| 19 mm, 2.68 g, coniato nel 323/324 | |

- 323

- Yet again Constantine was able to repel an invasion of Sarmatian Iazyges, as Zosimus seems to support, though he might have combined or confused the Sarmatian invasions of two separate years,[76] which had unsuccessfully besieged a city of Pannonia Inferior, identifiable with Campona,[6] a little south of the legionary fortress of Aquincum.

... The Sarmatians first attacked a city which had a constant garrison, where the part of the wall near the ground was built of stone and the upper parts in wood (which could be Campona[6]). The Sarmatians thought they could easily conquer the city, if they could set the wooden part of the wall on fire, so they lit a fire and shot the people on the walls. But while these people returned fire with darts and arrows, Constantine attacked them from behind, taking them by surprise, killing many and taking numerous prisoners, while the survivors fled..

— Zosimus, New History, 2.21.1–2.

- At the same time, the Goths[8][58] of Rausimodus decided to cross the Danube (further downstream) too and tried to raid the Roman territory of Moesia Inferior and Thrace.[9] Informed of this, Constantine left his general quarters in Thessalonica[10] and marched against them. Hearing of the arrival of the Emperor, the Goths decided to retreat to Wallachia,[77] but Constantine crossed the Ister, reached the Gothic invaders and massacred them in the battle which followed, managing to kill Rausimodus.[37][78]

Constantine [...] crossed over the Ister and attacked him [i.e. Rausimodus] as he fled towards a thickly wooded hill. He killed many barbarians, including Rausimodus himself, and afterwards he captured many more. Taking this multitude, which instantly raised its hands in surrender, he returned with them to his general quarters. After posting them in the cities [especially at Bononia[79]] he returned to Thessalonica.

— Zosimus, New History, 2.21.3 & 22.1.

- The barbarians had requested peace[9] and Constantine had nevertheless led an army into parts of the Empire which were not under his compitency (i.e. Moesia), but that of the other Augustus, Licinius – thereby initiating a new civil war between Constantine and Licinius.[70][80] Coinage continued to celebrate the Sarmatia devicta.[37][75][81]

- 324

- The civil war which followed saw the complete defeat of Licinius and Constantine's consecration as sole Augustus.[11] Remembering the recent war with the Goths, Constantine decided to construct some stone bridges in order to frighten the Barbarians north of the Danube: One connecting Oescus to the new fort of Sucidava on the north bank of the Danube,[82][83] another linking Transmarisca and the fort of Daphne which was also on the north bank of the Danube.[77][83] We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that the construction of these new fortifications dates to the later Gothic campaigns of 326–329.[84]

Third phase (324–337): the defence of the limes gothicus and the "reconquest" of Dacia

In this new phase, Constantine, now sole monarch of the Roman empire, not only managed to consolidate the entire defensive system along the Rhine and Danube, but also obtained important military successes and regained "control" over a good part of the territories which had been abandoned by Gallienus and Aurelian. This included the Agri decumates from the Alemanni, the plain south of the Tisza (Banat) from the Sarmatians and Oltenia & Wallachia from the Goths. These gains seem to be demonstrated by the coinage of the period and by new defensive constructions (Devil's Dykes and Brazda lui Novac).[85][86][87][83] Additionally, in this period, Constantine brought about a new series of reforms, completing those began some forty years earlier by Diocletian.[88] This process was accomplished gradually over the last thirteen years of his reign (324–337, the year of his death).

| Crispus: Follis[89] | |

|---|---|

| |

| FL IVL CRISPVS IVN NOB CAES, laureate head facing right; | ALEMANNIA DEVICTA ("Alemannia conquered"), facing Victory holding a trophy and a palm, with a prisoner seated at her feat; in the exergue is written SIRM). |

| 20 mma, 3.15 g, minted in 324/325 | |

- 324/325

- In the course of these two years, new military campaigns were conducted against the federation of the Alemanni by Constantine's son Crispus, which were celebrated coinage inscribed "Alemannia devicta (Alemannia conquered").[89] From this time, Constantine began to use Nicomedia as well as Serdica and Sirmium as his preferred Imperial residences.[90]

- 328[91]-331/332

- Once again, Constantine, along with his son Constantine II[92] was forced to intervene on the Upper Rhine, to defeat the Alemanni who had attempted to invade Gallic territory.[93] This war seems to have lasted many years, since the Emperor's sons were granted the title of Alamannicus Maximus only in 331/2.[86]

- 328

- [87] In this year it seems that there were new clashes with Germans, Sarmatians and Goths on the central and lower Danube and that Constantine was forced to cross the Ister once more, constructed a fortified bridge (between Oescus and Sucidava[83][87]) to take the war to Barbarian territory, such that the road leading to Romula was paved.[87] He devastated the local territory and reduced them to slavery, according to the account of Theophanes the Confessor.[94]

| Constantine II: Follis[91] | |

|---|---|

| |

| CONSTANTINVS IVN NOB CAES, laureate head facing right, with armoured bust; | ALEMANNIA DEVICTA ("Alemannia conquered"), facing Victory, holding a trophy and a palm, with a prisoner seated at her feat; in the exergue is written SIRM). |

| 3.40 g, minted in 324/325 | |

- 329

- The next year, all along the Lower Danube, the Goths went on the offensive, managing to penetrate to Moesia Inferior and Thrace, where they wrecked devastation, but Constantine managed to repel the barbarian hordes, construct a new bridge in Scythia Minor and attack their territory, as is recorded in his titulature for these years and in Anonymus Valesianus.[86][95] At the end of this campaign or that of the previous year, he seems to have received the title of Germanicus Maximus for the fourth time[37][96] and the title of Gothicus Maximus for the first time.[37]

- 331/332

- [87] The Visigoths, who had molested the allied Sarmatians, invading their territory[71] and then the Balkan provinces of the Romans, were defeated[79] near the modern city of Varna (Bulgaria),[97] by Constantine and his sixteen-year-old Caesar, Constantine II.[97] Reportedly, cold, hunger, and battle took the lives of 100,000 Goths. The survivors were forced to sue for peace with the Emperor, handing over hostages including the King's son Ariaric as a guarantee,[98] as well as a contingent of auxiliaries, in exchange for seed and grain.[97] Most importantly, a treaty was concluded with these people (foedus),[97] under which the Goths (presumably the Visigoths) were employed to defend the Imperial border[87] and provide 40,000 soldiers.[99][100] This peace endured until the time of Julian[101] or even to 375/376.[86] For these successes, he received the victory title of Gothicus Maximus for the second time,[37][96] as well as "Debellator gentium barbararum" ("Conqueror of barbarian peoples") and the coins of 332 and 333 named GOTHIA and SARMATIA as if they had become new Roman provinces.[102][103][104] Immediately following these events, Emperor Constantine may have begun construction of a new stretch of border defences, the so-called Brazda lui Novac,[83][105] which runs parallel to the north bank of the Danube from Drobeta, across the plain of eastern Wallachia to the Siret River,[72] surrounding the newly "reconquered" territories.[87] Not coincidentally, Aurelius Victor recounts that a bridge was built on the Danube (referring to the bridge built in 328) as well as numerous forts and bastions in diverse locations for protection of the borders.[106]

- 334

- [107] Two years later, the same Sarmatians who had requested the "friendly" intervention of the Romans, created new problems for the Emperor, when they were riven by internal conflict between the Limigantes and the Argaragantes.[71] It is said that the slaves (Limigantes) drove their masters (Argaragantes) from Banat, forcing Constantine to intervene militarily[107] in order to settle an enormous mass of "refugees" (allegedly 300,000 people) in Scythia Minor, Italia, Macedonia, Thrace,[86][93][108] Moesia Superior[71] and Pannonia Secunda.[71] Some maintain instead that Constantine launched a new military campaign into the plain south of the Tisza to restore order among the warring factions,[73] at the end of which Constantine received the victory title of Sarmaticus Maximus for the third time.[37][96][109] There are, after all, archaeological hints that Constantine had occupied part of the Banat mountains,[107] along the "old" Roman roads which led from Dierna and Lederata to Tibiscum seventeen years earlier.

- circa 335

- Jordanes recounts an episode datable to this period, in which the Vandals of Visimar, who inhabited the region between the Marisus and Danube rivers (perhaps a little northwest of Banat), clashed with the Goths of Geberic and were defeated. The survivors asked Constantine to be allowed into Roman territory, got permission and settled in Pannonia Inferior, where they remained in peace for around forty years, "obeying the laws of the Empire like the other inhabitants of the region."[110]

- 336

- Emperor Constantine achieved new successes beyond the Danube in the territories which had once been the Roman province of Dacia (abandoned by Aurelian), receiving the honorific title "Dacicus Maximus".[37][38][86] It cannot be coincidental that an inscription found near the former legionary fortress of Apulum (modern Alba Iulia) mentions a woman named Ulpia Constantia (reflecting connections to Trajan and Constantine).[111] This could give serious support to Emperor Julian's claim that Constantine reconquered all the territories controlled by Trajan – which included Dacia.[1]

Results

The equilibrium along the lower course of the Danube, after all the campaigns of Constantine and his sons, remained almost unchanged until around 375. The focus of the Emperor turned to the east, where a series of preparations were made for an imminent military campaign against the Sassanids, which was never carried out by Constantine on account of his death in May 337. For twenty five years, the Roman armies of Constantius II and then Julian, fought against the Sassanid armies with varying success (337–363). However the Lower Danube and Eastern borders remained, for almost thirty years, practically unchanged.

References

- Julian, De Caesaribus, 329c.

- Eutropius, Breviarium ab Urbe condita, 10.4.

- Zosimus, New History, 2.17.2.

- Zosimus, New History, 2.20.1.

- Inscription datable to 319 on which we find several victory titles:

Imperatori Caesari Flavio Constantino Maximo Pio Felici Invicto Augusto pontifici maximo, Germanico maximo III, Sarmatico maximo Britannico maximo, Arabico maximo, Medico maximo, Armenico maximo, Gothico maximo, tribunicia potestate XIIII, imperatori XIII, consuli IIII patri patriae, proconsuli, Flavius Terentianus vir perfectissimus praeses provinciae Mauretaniae Sitifensis numini maiestatique eius semper dicatissimus.

— CIL VIII, 8412 (p 1916) - A.Mócsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia, p.277.

- E.Horst, Costantino il Grande, Milano 1987, pp. 214 e 276.

- Aurelius Victor, De Caesaribus, 41.13.

- Anonymus Valesianus, 5.21.

- Zosimus, New History, 2.22.3.

- Zosimus, New History, 2.28.2.

- Grant, p. 265.

- Scarre, p. 197-198.

- Cameron, p. 46.

- Eutropius, Breviarium ab Urbe condita, 10.1.

- Zosimus, Storia nuova, 2.9.1.

- Eutropius, Breviarium ab Urbe condita, 10.2.

- Panegyrici latini, 7.3.3.

- Orosius, History against the Pagans, 7.26.1.

- Aurelius Victor, De Caesaribus, 40.2.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, 8.13.14.

- Lactantius, De mortibus persecutorum, 24.8.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, pp. 27–28; Barnes, New Empire, p. 5; Lenski, pp. 61–62; Odahl, pp. 78–79.

- Eutropius, Breviarium ab Urbe condita, 10.3.

- J. R. González, Historia de las legiones romanas, pp. 709–710.

- J. R. González, Historia de las legiones romanas, pp. 711–712.

- E. Horst, Costantino il grande, Milano 1987, pp. 84–85.

- E. Horst, Costantino il grande, Milano 1987, p. 88.

- E. Horst, Costantino il grande, Milano 1987, pp. 92–93 e 96.

- E. Horst, Costantino il grande, Milano 1987, p. 90.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Constantinus I, VI 776.

- E. Horst, Costantino il grande, Milano 1987, p. 98.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Life of Constantine, 1.25.1.

- Panegyrici latini, 7.6 QUI Archived 2016-04-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- Anselmo Baroni, Cronologia della storia romana dal 235 al 476, p. 1026.

- Panegyrici latini, 7.12–13 QUI Archived 2016-04-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- Barnes, T.D. "Victories of Constantine". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 20: 149–155.

- CIL VI, 40776

- Y. Le Bohec, Armi e guerrieri di Roma antica. Da Diocleziano alla caduta dell'impero, Roma 2008. pp. 46 & 53.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, History, 17.1.11; 17.10.4; 20.10.2.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Constantinus I, VI 774.

- Y. Le Bohec, Armi e guerrieri di Roma antica. Da Diocleziano alla caduta dell'impero, Roma 2008, p. 46.

- CIL XIII, 8502.

- Anselmo Baroni, Cronologia della storia romana dal 235 al 476, p. 1027.

- E. Horst, Costantino il grande, Milano 1987, p. 99.

- C.R.Whittaker, Frontiers of the Roman empire. A social ad economic study, Baltimora & London, 1997, p.162.

- Panegyrici latini, 7.18–19.

- Lactantius, De mortibus persecutorum, 29.8.

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, pp. 34–35; Elliott, p. 43; Lenski, pp. 65–66; Odahl, p. 93; Pohlsander, Emperor Constantine, p. 17; Potter, p. 352; E. Horst, Costantino il grande, Milano 1987, pp. 124–125.

- Hans Schönberger, "The roman frontier in Germany: an archaeological survey", in Journal of Roman Studies 1969, p.180. The fortifications at Bitburg, Neumagen and Jünkerath, as well as the fort of Pachten (152x134 metres).

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Constantinus I, Constantinus I, VI 823; Depeyrot 18/2; Alföldi 19.

- Lactantius, De mortibus persecutorum, 44; Zosimus, New History, 2.16; Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribus, 40.23; Panegyrici latini, 9.16 ss. (Eumenius) and 10.28 ss. (Nazarius).

- Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, pp. 42–44.

- Zosimus, New History, 2.18.1.

- E. Horst, Costantino il grande, Milano 1987, p. 186.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Constantinus I, VII, 823.

- Panegyrici latini, IX, 21.5–22, 6; X, 16.5 QUI Archived 2016-04-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- Y. Le Bohec, Armi e guerrieri di Roma antica. Da Diocleziano alla caduta dell'impero, Roma 2008. p. 50.

- CIL XI, 5265; AE 1903, 264; CIL III, 204 (p 973); CIL VI, 1135 (p 4327); CIL VI, 1142 (p 3071, 4329); CIL VI, 1144 (p 3071, 3778, 4329); CIL VI, 1146 (p 3071, 4329); CIL VIII, 7006 (p 1847); CIL VIII, 7007 (p 1847); CIL VIII, 12064; CIL XI, 5265.

- J.Burckhardt, L'età di Costantino il Grande, Firenze 1990, p.345.

- Zosimus, New History, 2.18.2–5.

- Zosimus, New History, 2.19.1–3.

- Anonymus Valesianus, 2.3; Zonaras, Epitome of Histories, 12.33; Lactantius, De mortibus persecutorum, 24.4.

- E.Horst, Costantino il Grande, Milano 1987, p.82; A.Mócsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia, p.276.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Constantinus I, VII 87.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Constantinus I, VII 122.

- E.Horst, Costantino il Grande, Milano 1987, pp. 215–219.

- E.Horst, Costantino il Grande, Milano 1987, p. 241.

- Zosimus, New History, 2.21.1.

- Anselmo Baroni, Cronologia della storia romana dal 235 al 476, p. 1028.

- A.Mócsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia, p.279.

- V.A. Maxfield, L'Europa continentale, pp. 210–213.

- C.R.Whittaker, Frontiers of the Roman empire. A social ad economic study, Baltimora & London, 1997, pp. 176–178.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Constantinus I, VII, n. 257, 257v & 435v (Arles); VII, n.289 & 290 (London); VII, 48 (Sirmium); VII, n.429, 435 & 435S (Trier).

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Constantinus I, VII 290 (R2).

- Zosimus, New History, 2.21.2.

- Herman Schreiber, I Goti, Milano 1981, p. 78.

- Zosimus, New History, 2.21.3.

- A.Mócsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia, p.278.

- E.Horst, Costantino il Grande, Milano 1987, pp. 242–244.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Constantinus I, VII, 48, 257 e 257v (Arles).

- AE 1949, 204, AE 1950, 75d e AE 1939, 19; AE 1950, 75d; AE 1976, 582e.

- C.R.Whittaker, Frontiers of the Roman empire. A social ad economic study, Baltimora & London, 1997, p. 185.

- See this important site on the archaeology of the limes of Moesia Inferior in the fourth century on apar.archaeology.ro Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- V.A. Makfield, "L'Europa continentale", in Il mondo di Roma imperiale, edited by J. Wacher, Roma-Bari 1989, pp. 210–213.

- Y. Le Bohec, Armi e guerrieri di Roma antica. Da Diocleziano alla caduta dell'impero, Roma 2008. p. 52.

- R.Ardevan & L.Zerbini, La Dacia romana, p.210.

- Yann Le Bohec, Armi e guerrieri di Roma antica. Da Diocleziano alla caduta dell'impero, Roma, 2008, p. 53.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Crispus, VII 49; LRBC 803.

- E.Horst, Costantino il Grande, Milano 1987, p. 276.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, Constantinus II, VII, 50.

- CIL III, 7000; CIL III, 12483.

- Anselmo Baroni, Cronologia della storia romana dal 235 al 476, p. 1029.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, A.M. 5818.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia, A.M. 5820.

- CIL II, 481.

- E. Horst, Costantino il grande, Milano 1987, p. 297.

- Annales Valesiani, VI, 31.

- Jordanes, De origine actibusque Getarum, 21.

- Anonymus Valesianus, 1.31.

- C.R.Whittaker, Frontiers of the Roman empire. A social ad economic study, Baltimora & London, 1997, p. 186.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, volume 7, da Costantino I a Licinio (313–337), by P.M. Bruun, 1966, p. 215.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Life of Constantine, 1.8.2.

- Sozomen, Ecclesiastica Historia, 1.8.

- A.Mócsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia, pp.280–282.

- Aurelius Victor, De Caesaribus, 41.18.

- R.Ardevan & L.Zerbini, La Dacia romana, p.211.

- Annales Valesiani, VI, 32.

- Y.Le Bohec, Armi e guerrieri di Roma antica. Da Diocleziano alla caduta dell'impero, Roma, 2008, p.53; C.Scarre, Chronicle of the roman emperors, New York, 1999, p.214.

- Jordanes, De origine actibusque Getarum, 22.

- CIL III, 1203.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae; Latin text and English translation.

- Anonymus Valesianus, Book 5; Latin text and English translation.

- Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribus and De Vita et Moribus Imperatorum Romanorum; Latin text and English translation.

- Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum; Website on the Latin inscriptions.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Life of Constantine.

- Eutropius, Breviarium historiae romanae (Latin Text), 9–10

- Julian, De Caesaribus.

- Jordanes, De origine actibusque Getarum; Latin text.

- Lactantius, De mortibus persecutorum, 26; Latin text.

- Orosius, Historiarum adversus paganos libri septem, book 7 Latin text.

- Panegyrici latini, 7 & 10 Latin text.

- Roman Imperial Coinage, VII.

- Sozomen, Ecclesiastica Historia, Book 1.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronographia.

- Zosimus, New History, Books 1–2.

Modern sources

- Radu Ardevan & Livio Zerbini, La Dacia romana, Soveria Mannelli 2007. ISBN 978-88-498-1827-7

- Barnes, Timothy D. (1976). "Victories of Constantine". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 20.

- Barnes, Timothy (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge: MA Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-16531-1.

- Barnes, Timothy (1982). The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine. Cambridge: MA Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-7837-2221-4.

- Baroni, Anselmo (2009). Cronologia della storia romana dal 235 al 476. Milano: Storia Einaudi dei Greci e dei Romani, vol.19.

- Cameron, Averil (1995). Il tardo impero romano. Milano. ISBN 88-15-04887-1.

- Carrié, Jean-Michel (2008). Eserciti e strategie. Milano: in Storia dei Greci e dei Romani, vol.18, La Roma tardo-antica, per una preistoria dell'idea di Europa.

- González, Julio Rodríguez (2003). Historia de las legiones Romanas. Madrid.

- Grant, Michel (1984). Gli imperatori romani, storia e segreti. Roma. ISBN 88-541-0202-4.

- Horst, Eberhard (1987). Costantino il Grande. Milano.

- Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin (1986). The Later Roman Empire: 284-602. Baltimora. ISBN 0-8018-3285-3.

- Le Bohec, Yann (2008). Armi e guerrieri di Roma antica. Da Diocleziano alla caduta dell'impero. Roma. ISBN 978-88-430-4677-5.

- Maxfield, V.A. (1989). L'Europa continentale. Roma-Bari: in Il mondo di Roma imperiale edited by J. Wacher.

- Mazzarino, Santo (1973). L'impero romano. Bari. ISBN 88-420-2377-9. ISBN 88-420-2401-5.

- Mócsy, András (1974). Pannonia and Upper Moesia. Londra.

- Oliva, Pavel (1962). Pannonia and the onset of crisis in the roman empire. Praga.

- Rémondon, Roger (1975). La crisi dell'impero romano, da Marco Aurelio ad Anastasio. Milano.

- Scarre, Chris (1999). Chronicle of the roman emperors. New York. ISBN 0-500-05077-5.

- Schönberger, H. (1969). "The Roman Frontier in Germany: an Archaeological Survey". Journal of Roman Studies.

- Southern, Pat (2001). The Roman Empire: from Severus to Constantine. Londra & New York. ISBN 0-415-23944-3.

- Whittaker, C.R. (1997). Frontiers of the Roman empire. A social and economic study. Baltimora & London.

- Williams, Stephen (1995). Diocleziano. Un autocrate riformatore. Genova. ISBN 88-7545-659-3.

Related links

- Constantine I

- Crispus

- Constantine II

- Constantius II

- Constans I

- Limes (Roman Empire)

- Germanic peoples

- Sarmatians