Coronary thrombosis

Coronary thrombosis is defined as the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel of the heart. This blood clot may then restrict blood flow within the heart, leading to heart tissue damage, or a myocardial infarction, also known as a heart attack.[1]

| Coronary thrombosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

Coronary thrombosis is most commonly caused as a downstream effect of atherosclerosis, a buildup of cholesterol and fats in the artery walls. The smaller vessel diameter allows less blood to flow and facilitates progression to a myocardial infarction. Leading risk factors for coronary thrombosis are high LDL cholesterol, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and hypertension.[2]

A coronary thrombus is asymptomatic until it causes significant obstruction, leading to various forms of angina or eventually a myocardial infarction. Common warning symptoms are crushing chest pain, shortness of breath, and upper body discomfort.[2]

Terminology

Thrombosis is defined as the formation of a thrombus (blood clot) inside a blood vessel, leading to obstruction of blood flow within the circulatory system. Coronary thrombosis refers to the formation and presence of thrombi in the coronary arteries of the heart. Note that the heart does not contain veins, but rather coronary sinuses that serve the purpose of returning de-oxygenated blood from the heart muscle.

A thrombus is a type of embolism, a more general term for any material that partially or fully blocks a blood vessel. An atheroembolism, or cholesterol embolism, is when an atherosclerotic plaque ruptures and becomes an embolism.

Atherosclerosis is the progressive thickening of blood vessels and plaque formation that eventually can lead to coronary artery disease (CAD).

Pathogenesis

Coronary thrombosis and myocardial infarction are sometimes used as synonyms, although this is technically inaccurate as the thrombosis refers to the blocking of blood vessels with a thrombus, while myocardial infarction refers to heart tissue death due to the consequent loss of blood flow to the heart. Due to extensive collateral circulation, a coronary thrombus does not necessarily cause tissue death and may be asymptomatic.

The formation of coronary thrombosis generally follows the same mechanism as other blood clots in the body, the coagulation cascade. Also applicable is the Virchow's triad of blood stasis, endothelial injury, and hypercoagulable state. Atherosclerosis contributes to coronary thrombosis formation by facilitating blood stasis as well as causing local endothelial injury.

Due to the large number of cases of myocardial infarction leading to death and disease in the world, there has been extensive study towards the generation of clots specifically in the coronary arteries. Some areas of focus:

- Coronary thrombosis can be a complication associated with drug-eluting stents.[3] These stents that are placed to open up narrowed arteries are often infused with medicine to prevent repeat stenosis. However, they may actually lead to an increased coronary thrombus formation due to increased tissue factor expression and delayed healing within the vessels. Furthermore, the downstream endothelium has been shown to be impaired, leading to an environment that favors formation of clots. Evidence remains inconclusive about whether these risks outweigh the benefit of a coronary arterial stent.[3][4]

- Inflammation may play a causal role in coronary artery disease and subsequent myocardial infarction due to coronary thrombosis. Increased levels of inflammation may lead to higher risk of clotting as well as an increased risk of stent/device subsequent thrombosis. There is an ongoing search for inflammatory biomarkers that can help determine at-risk individuals.[5]

- Coronary "microembolization" is being explored as a focal point for coronary thrombus formation and subsequent sudden death due to acute myocardial infarction.[6]

- High mobility group box-1 (HMGB-1) proteins as important mediators in thrombus formation.[7]

- Coronary sinus thrombosis as a severe complication after procedures.[8] The coronary sinus is the venous counterpart to the coronary arteries, where de-oxygenated blood returns from heart tissue. A large thrombus here slows overall blood circulation to heart tissue as well as may mechanically compress a coronary artery.[8]

Diagnosis

Clinical signs of MI or angina if coronary thrombus is symptomatic:

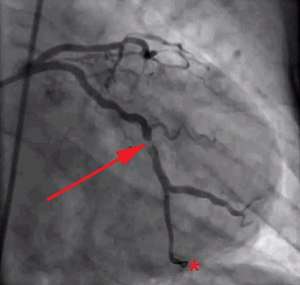

Imaging modalities used to evaluate the presence of coronary thrombi:[9]

Postmortem examiners may look for Lines of Zahn, to determine whether blood clotted in the heart vessels before or after death.[11]

Management /Prevention

Management of symptomatic coronary thrombosis follows established treatment algorithms for myocardial infarction.

Treatment options include:[12]

- emergency coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)

- stent implantation

- intracoronary thrombolysis

- anticoagulation with heparin or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors

- thrombus aspiration as reperfusion strategy

- platelet P2Y12 receptor inhibitors: The CURE trial in 2001 determined that the addition of clopidogrel showed a positive effect on cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal MI, and stroke at the cost of an increased risk of major bleeding.[13]

To address the possibility of identifying and treating asymptomatic coronary artery disease to prevent development of coronary thrombosis, the COURAGE trial was published in 2018.[14] It determined that preemptive treatment with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) did not lead to a difference in death or myocardial infarction over a 15 year period.[14]

There are numerous treatments currently being studied for management and prevention of coronary thrombosis. Statin drugs, in addition to their primary cholesterol-lowering mechanisms of action, have been studied to target a number of pathways that may decrease coronary inflammation and subsequent thrombosis.[15]

Another realm of potential treatments in early stages of adoption is in therapeutic use of contrast ultrasound on thrombus dissolution.[16]

Notable people

See also

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

References

- Klatt MD, Edward C. "Atherosclerosis". Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library. The University of Utah. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- "Heart Attack | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-16.

- Lüscher, Thomas F.; Steffel, Jan; Eberli, Franz R.; Joner, Michael; Nakazawa, Gaku; Tanner, Felix C.; Virmani, Renu (27 February 2007). "Drug-Eluting Stent and Coronary Thrombosis: Biological Mechanisms and Clinical Implications". Circulation. 115 (8): 1051–8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675934. PMID 17325255.

- Borovac, Josip Anđelo; D'Amario, Domenico; Niccoli, Giampaolo (September 2017). "Neoatherosclerosis and Late Thrombosis After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Translational Cardiology and Comparative Medicine from Bench to Bedside". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 90 (3): 463–470. ISSN 1551-4056. PMC 5612188. PMID 28955184.

- Sexton, Travis; Smyth, Susan S. (January 2014). "Novel mediators and biomarkers of thrombosis". Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis. 37 (1): 1–3. doi:10.1007/s11239-013-1034-5. ISSN 1573-742X. PMC 4086911. PMID 24356857.

- Skyschally, Andreas; Erbel, Raimund; Heusch, Gerd (April 2003). "Coronary microembolization". Circulation Journal. 67 (4): 279–286. doi:10.1253/circj.67.279. ISSN 1346-9843. PMID 12655156.

- Wu, Han; Li, Ran; Pei, Li-Gang; Wei, Zhong-Hai; Kang, Li-Na; Wang, Lian; Xie, Jun; Xu, Biao (2018). "Emerging Role of High Mobility Group Box-1 in Thrombosis-Related Diseases". Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry: International Journal of Experimental Cellular Physiology, Biochemistry, and Pharmacology. 47 (4): 1319–1337. doi:10.1159/000490818. ISSN 1421-9778. PMID 29940562.

- W, Masood; Kk, Sitammagari. "Coronary Sinus Thrombosis". PubMed. PMID 29939583. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- Lablanche, J. M.; Perrard, G.; Chmait, A.; Meurice, T.; Sudre, A.; Van Belle, E. (November 2002). "[Coronary thrombosis imaging in humans]". Archives Des Maladies Du Coeur Et Des Vaisseaux. 95 Spec No 7: 15–20. ISSN 0003-9683. PMID 12500600.

- Abanador-Kamper, Nadine; Kamper, Lars; Castello-Boerrigter, Lisa; Haage, Patrick; Seyfarth, Melchior (January 2019). "MRI findings in patients with acute coronary syndrome and unobstructed coronary arteries". Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology (Ankara, Turkey). 25 (1): 28–34. doi:10.5152/dir.2018.18004. ISSN 1305-3612. PMC 6339625. PMID 30582569.

- Baumann Kreuziger, Lisa; Slaughter, Mark S.; Sundareswaran, Kartik; Mast, Alan E. (November 2018). "Clinical Relevance of Histopathologic Analysis of HeartMate II Thrombi". ASAIO journal (American Society for Artificial Internal Organs: 1992). 64 (6): 754–759. doi:10.1097/MAT.0000000000000759. ISSN 1538-943X. PMC 6093800. PMID 29461277.

- Akcay, Murat (July 2018). "Evaluation of thrombotic left main coronary artery occlusions; old problem, different treatment approaches". Indian Heart Journal. 70 (4): 573–574. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2017.09.006. ISSN 2213-3763. PMC 6117801. PMID 30170655.

- "CURE - Wiki Journal Club". www.wikijournalclub.org. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- "Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation". American College of Cardiology. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- Sexton, Travis; Wallace, Eric L.; Smyth, Susan S. (2016). "Anti-Thrombotic Effects of Statins in Acute Coronary Syndromes: At the Intersection of Thrombosis, Inflammation, and Platelet-Leukocyte Interactions". Current Cardiology Reviews. 12 (4): 324–329. doi:10.2174/1573403x12666160504100312. ISSN 1875-6557. PMC 5304247. PMID 27142048.

- Slikkerveer, Jeroen; Juffermans, Lynda Jm; van Royen, Niels; Appelman, Yolande; Porter, Thomas R.; Kamp, Otto (February 2019). "Therapeutic application of contrast ultrasound in ST elevation myocardial infarction: Role in coronary thrombosis and microvascular obstruction". European Heart Journal. Acute Cardiovascular Care. 8 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1177/2048872617728559. ISSN 2048-8734. PMC 6376593. PMID 28868906.