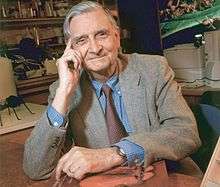

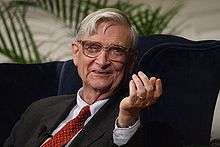

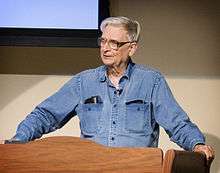

E. O. Wilson

Edward Osborne Wilson (born June 10, 1929), usually cited as E. O. Wilson, is an American biologist, naturalist, and writer. His biological specialty is myrmecology, the study of ants, on which he has been called the world's leading expert.[3][4]

Wilson has been called "the father of sociobiology" and "the father of biodiversity"[5] for his environmental advocacy, and his secular-humanist and deist ideas pertaining to religious and ethical matters.[6] Among his greatest contributions to ecological theory is the theory of island biogeography, which he developed in collaboration with the mathematical ecologist Robert MacArthur. This theory served as the foundation of the field of conservation area design, as well as the unified neutral theory of biodiversity of Stephen Hubbell.

Wilson is the Pellegrino University Research Professor, Emeritus in Entomology for the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, a lecturer at Duke University,[7] and a Fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. He is a Humanist Laureate of the International Academy of Humanism.[8][9] He is a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction (for On Human Nature in 1979, and The Ants in 1991) and a New York Times bestselling author for The Social Conquest of Earth,[10] Letters to a Young Scientist,[10] and The Meaning of Human Existence.

Early life

Wilson was born in Birmingham, Alabama. According to his autobiography Naturalist, he grew up mostly around Washington, D.C. and in the countryside around Mobile, Alabama.[11] From an early age, he was interested in natural history. His parents, Edward and Inez Wilson, divorced when he was seven. The young naturalist grew up in several cities and towns, moving around with his father and his stepmother.

In the same year that his parents divorced, Wilson blinded himself in one eye in a fishing accident. He suffered for hours, but he continued fishing.[11] He did not complain because he was anxious to stay outdoors. He did not seek medical treatment.[11] Several months later, his right pupil clouded over with a cataract.[11] He was admitted to Pensacola Hospital to have the lens removed.[11] Wilson writes, in his autobiography, that the "surgery was a terrifying [19th] century ordeal".[11] Wilson was left with full sight in his left eye, with a vision of 20/10.[11] The 20/10 vision prompted him to focus on "little things": "I noticed butterflies and ants more than other kids did, and took an interest in them automatically."[11]

Although he had lost his stereoscopic vision, he could still see fine print and the hairs on the bodies of small insects.[11] His reduced ability to observe mammals and birds led him to concentrate on insects.

At the age of nine, Wilson undertook his first expeditions at the Rock Creek Park in Washington, DC. He began to collect insects and he gained a passion for butterflies. He would capture them using nets made with brooms, coat hangers, and cheesecloth bags.[11] Going on these expeditions led to Wilson's fascination with ants. He describes in his autobiography how one day he pulled the bark of a rotting tree away and discovered citronella ants underneath.[11] The worker ants he found were "short, fat, brilliant yellow, and emitted a strong lemony odor".[11] Wilson said the event left a "vivid and lasting impression on [him]".[11] He also earned the Eagle Scout award and served as Nature Director of his Boy Scout summer camp. At the age of 18, intent on becoming an entomologist, he began by collecting flies, but the shortage of insect pins caused by World War II caused him to switch to ants, which could be stored in vials. With the encouragement of Marion R. Smith, a myrmecologist from the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, Wilson began a survey of all the ants of Alabama. This study led him to report the first colony of fire ants in the US, near the port of Mobile.[12]

Education

Concerned that he might not be able to afford to go to a university, Wilson tried to enlist in the United States Army. He planned to earn U.S. government financial support for his education, but failed the Army medical examination due to his impaired eyesight.[11] Wilson was able to afford to enroll in the University of Alabama after all, earning his B.S. and M.S. degrees in biology there in 1950. In 1951 he transferred to Harvard University.[11]

Appointed to the Harvard Society of Fellows, he could travel on overseas expeditions, collecting ant species of Cuba and Mexico and travel the South Pacific, including Australia, New Guinea, Fiji, New Caledonia and Sri Lanka. In 1955, he received his PhD and married Irene Kelley.[13]

Career

From 1956 until 1996, Wilson was part of the faculty of Harvard. He began as an ant taxonomist and worked on understanding their microevolution, how they developed into new species by escaping environmental disadvantages and moving into new habitats. He developed a theory of the "taxon cycle".[13]

Just after completing his PhD in 1955, Wilson started supervising Stuart A. Altmann on the social behavior of rhesus macaques, which gave Wilson a first impetus to imagine sociobiology as a global theory of animal social behavior.[14]

He collaborated with mathematician William Bossert, and discovered the chemical nature of ant communication, via pheromones. In the 1960s he collaborated with mathematician and ecologist Robert MacArthur in developing the theory of species equilibrium. In the 1970s he and Daniel S.Simberloff tested this theory on tiny mangrove islets in the Florida Keys. They eradicated all insect species and observed the re-population by new species. Wilson and MacArthur's book The Theory of Island Biogeography became a standard ecology text.[13]

In 1971, he published the book The Insect Societies about the biology of social insects like ants, bees, wasps and termites. In 1973, Wilson was appointed 'Curator of Insects' at the Museum of Comparative Zoology. In 1975, he published the book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis applying his theories of insect behavior to vertebrates, and in the last chapter, humans. He speculated that evolved and inherited tendencies were responsible for hierarchical social organisation among humans. In 1978 he published On Human Nature, which dealt with the role of biology in the evolution of human culture and won a Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.[13]

In 1981 after collaborating with Charles Lumsden, he published Genes, Mind and Culture, a theory of gene-culture coevolution. In 1990 he published The Ants, co-written with Bert Hölldobler, his second Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.[13]

In the 1990s, he published The Diversity of Life (1992), an autobiography: Naturalist (1994), and Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (1998) about the unity of the natural and social sciences.[13]

Retirement

In 1996, Wilson officially retired from Harvard University, where he continues to hold the positions of Professor Emeritus and Honorary Curator in Entomology. He founded the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation, which finances the PEN/E. O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award and is an "independent foundation" at the Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University. Wilson became a special lecturer at Duke University as part of the agreement.[15]

Wilson has published the following books during the 21st century:

- The Future of Life, 2002

- Pheidole in the New World: A Dominant, Hyperdiverse Ant Genus, 2003

- From So Simple a Beginning: Darwin's Four Great Books, 2005

- The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth, September 2006

- Nature Revealed: Selected Writings, 1949–2006

- The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies, 2009

- Anthill: A Novel, April 2010

- Kingdom of Ants: Jose Celestino Mutis and the Dawn of Natural History in the New World, 2010

- The Leafcutter Ants: Civilization by Instinct, 2011

- The Social Conquest of Earth, 2012

- Letters to a Young Scientist, 2014

- A Window on Eternity: A Biologist's Walk Through Gorongosa National Park, 2014

- The Meaning of Human Existence, 2014

- Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life, 2016

- Genesis: The Deep Origin of Societies, 2019

Wilson and his wife, Irene, reside in Lexington, Massachusetts. His daughter, Catherine, and her husband, Jonathan, reside in nearby Stow, Massachusetts.[13]

Work

Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, 1975

Wilson used sociobiology and evolutionary principles to explain the behavior of social insects and then to understand the social behavior of other animals, including humans, thus establishing sociobiology as a new scientific field. He argued that all animal behavior, including that of humans, is the product of heredity, environmental stimuli, and past experiences, and that free will is an illusion. He has referred to the biological basis of behavior as the "genetic leash".[16]:127–128 The sociobiological view is that all animal social behavior is governed by epigenetic rules worked out by the laws of evolution. This theory and research proved to be seminal, controversial, and influential.[17]:210ff

Wilson has argued that the unit of selection is a gene, the basic element of heredity. The target of selection is normally the individual who carries an ensemble of genes of certain kinds. With regard to the use of kin selection in explaining the behavior of eusocial insects, the "new view that I'm proposing is that it was group selection all along, an idea first roughly formulated by Darwin."[18]

Sociobiological research was at the time particularly controversial with regard to its application to humans.[19] The theory established a scientific argument for rejecting the common doctrine of tabula rasa, which holds that human beings are born without any innate mental content and that culture functions to increase human knowledge and aid in survival and success.[20] In the final chapter of the book Sociobiology Wilson argues that the human mind is shaped as much by genetic inheritance as it is by culture if not more. There are, Wilson suggests in the chapter, limits on just how much influence social and environmental factors can have in altering human behavior.[21]

Reception

Sociobiology was initially met with substantial criticism. Several of Wilson's colleagues at Harvard,[22] such as Richard Lewontin and Stephen Jay Gould, were strongly opposed to his ideas regarding sociobiology. Gould, Lewontin, and others from the Sociobiology Study Group from the Boston area wrote "Against 'Sociobiology'" in an open letter criticizing Wilson's "deterministic view of human society and human action".[23] Although attributed to members of the Sociobiology Study Group, it seems that Lewontin was the main author.[24] In a 2011 interview, Wilson said, "I believe Gould was a charlatan. I believe that he was ... seeking reputation and credibility as a scientist and writer, and he did it consistently by distorting what other scientists were saying and devising arguments based upon that distortion."[25]

Marshall Sahlins's 1976 work The Use and Abuse of Biology was a direct criticism of Wilson's theories.[26]

There was also political opposition. Sociobiology re-ignited the nature and nurture debate. Wilson was accused of racism, misogyny, and sympathy to eugenics.[27] In one incident in November 1978, his lecture was attacked by the International Committee Against Racism, a front group of the Marxist Progressive Labor Party, where one member poured a pitcher of water on Wilson's head and chanted "Wilson, you're all wet" at an AAAS conference.[28] Wilson later spoke of the incident as a source of pride: "I believe ... I was the only scientist in modern times to be physically attacked for an idea."[29]

Objections from evangelical Christians included those of Paul E. Rothrock in 1987: "... sociobiology has the potential of becoming a religion of scientific materialism."[30] Philosopher Mary Midgley encountered Sociobiology in the process of writing Beast and Man (1979)[31] and significantly rewrote the book to offer a critique of Wilson's views. Midgley praised the book for the study of animal behavior, clarity, scholarship, and encyclopedic scope, but extensively critiqued Wilson for conceptual confusion, scientism, and anthropomorphism of genetics.[32]

The book and its reception were mentioned in Jonathan Haidt's book The Righteous Mind.[33] as well as Matt Ridley's The Agile Gene.

On Human Nature, 1978

Wilson wrote in his 1978 book On Human Nature, "The evolutionary epic is probably the best myth we will ever have." Wilson's use of the word "myth" provides people with meaningful placement in time celebrating shared heritage.[34] Wilson's fame prompted use of the morphed phrase epic of evolution.[6] The book won the Pulitzer Prize in 1979.[35]

The Ants, 1990

Wilson, along with Bert Hölldobler, carried out a systematic study of ants and ant behavior,[36] culminating in the 1990 encyclopedic work The Ants. Because much self-sacrificing behavior on the part of individual ants can be explained on the basis of their genetic interests in the survival of the sisters, with whom they share 75% of their genes (though the actual case is some species' queens mate with multiple males and therefore some workers in a colony would only be 25% related), Wilson argued for a sociobiological explanation for all social behavior on the model of the behavior of the social insects.

Wilson has said in reference to ants "Karl Marx was right, socialism works, it is just that he had the wrong species".[37] He meant that while ants and other eusocial species appear to live in communist-like societies, they only do so because they are forced to do so from their basic biology, as they lack reproductive independence: worker ants, being sterile, need their ant-queen in order to survive as a colony and a species, and individual ants cannot reproduce without a queen and are thus forced to live in centralized societies. Humans, however, do possess reproductive independence so they can give birth to offspring without the need of a "queen", and in fact humans enjoy their maximum level of Darwinian fitness only when they look after themselves and their offspring, while finding innovative ways to use the societies they live in for their own benefit.[38]

Consilience, 1998

In his 1998 book Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, Wilson discussed methods that have been used to unite the sciences, and might be able to unite the sciences with the humanities. Wilson used the term "consilience" to describe the synthesis of knowledge from different specialized fields of human endeavor. He defined human nature as a collection of epigenetic rules, the genetic patterns of mental development. He argued that culture and rituals are products, not parts, of human nature. He said art is not part of human nature, but our appreciation of art is. He suggested that concepts such as art appreciation, fear of snakes, or the incest taboo (Westermarck effect) could be studied by scientific methods of the natural sciences and be part of interdisciplinary research.

The book was mentioned in Jonathan Haidt's book The Righteous Mind.[33]

Spiritual and political beliefs

Scientific humanism

Wilson coined the phrase scientific humanism as "the only worldview compatible with science's growing knowledge of the real world and the laws of nature".[39] Wilson argued that it is best suited to improve the human condition. In 2003, he was one of the signers of the Humanist Manifesto.[40]

God and religion

On the question of God, Wilson has described his position as provisional deism[41] and explicitly denied the label of "atheist", preferring "agnostic".[42] He has explained his faith as a trajectory away from traditional beliefs: "I drifted away from the church, not definitively agnostic or atheistic, just Baptist & Christian no more."[16] Wilson argues that the belief in God and rituals of religion are products of evolution.[43] He argues that they should not be rejected or dismissed, but further investigated by science to better understand their significance to human nature. In his book The Creation, Wilson suggests that scientists ought to "offer the hand of friendship" to religious leaders and build an alliance with them, stating that "Science and religion are two of the most potent forces on Earth and they should come together to save the creation."[44]

Wilson made an appeal to the religious community on the lecture circuit at Midland College, Texas, for example, and that "the appeal received a 'massive reply'", that a covenant had been written and that a "partnership will work to a substantial degree as time goes on".[45]

In a New Scientist interview published on January 21, 2015, Wilson said that "Religion 'is dragging us down' and must be eliminated 'for the sake of human progress'", and "So I would say that for the sake of human progress, the best thing we could possibly do would be to diminish, to the point of eliminating, religious faiths."[46][47]

Ecology

Wilson has said that, if he could start his life over he would work in microbial ecology, when discussing the reinvigoration of his original fields of study since the 1960s.[48] He studied the mass extinctions of the 20th century and their relationship to modern society, and in 1998 argued for an ecological approach at the Capitol:

Now when you cut a forest, an ancient forest in particular, you are not just removing a lot of big trees and a few birds fluttering around in the canopy. You are drastically imperiling a vast array of species within a few square miles of you. The number of these species may go to tens of thousands. ... Many of them are still unknown to science, and science has not yet discovered the key role undoubtedly played in the maintenance of that ecosystem, as in the case of fungi, microorganisms, and many of the insects.[49]

Wilson has been part of the international conservation movement, as a consultant to Columbia University's Earth Institute, as a director of the American Museum of Natural History, Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy and the World Wildlife Fund.[13]

Understanding the scale of the extinction crisis has led him to advocate for forest protection,[49] including the "Act to Save America's Forests", first introduced in 1998, until 2008, but never passed.[50] The Forests Now Declaration calls for new markets-based mechanisms to protect tropical forests.[51] In 2014, Wilson called for setting aside 50% of the earth's surface for other species to thrive in as the only possible strategy to solve the extinction crisis.[52]

Awards and honors

Wilson's scientific and conservation honors include:

- Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, elected 1959[53]

- Member of the National Academy of Sciences, elected 1969[54]

- U.S. National Medal of Science, 1976

- Leidy Award, 1979, from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia[55]

- Pulitzer Prize for On Human Nature, 1979[56]

- Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, 1984

- ECI Prize, International Ecology Institute, terrestrial ecology, 1987

- honorary doctorate from the Faculty of Mathematics and Science at Uppsala University, Sweden, 1987[57]

- Academy of Achievement Golden Plate Award, 1988[58]

- Crafoord Prize, 1990, a prize awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences[59]

- Pulitzer Prize for The Ants (with Bert Hölldobler), 1991

- International Prize for Biology, 1993

- Carl Sagan Award for Public Understanding of Science, 1994

- The National Audubon Society's Audubon Medal, 1995

- Time Magazine's 25 Most Influential People in America, 1995

- Benjamin Franklin Medal for Distinguished Achievement in the Sciences of the American Philosophical Society, 1998.[60]

- American Humanist Association's 1999 Humanist of the Year

- Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science, 2000

- Nierenberg Prize, 2001

- Distinguished Eagle Scout Award 2004

- Dauphin Island Sea Lab christened its newest research vessel the R/V E.O. Wilson in 2005.

- Linnean Tercentenary Silver Medal, 2006

- Addison Emery Verrill Medal from the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 2007

- TED Prize 2007[61] given yearly to honor a maximum of three individuals who have shown that they can, in some way, positively impact life on this planet.

- XIX Premi Internacional Catalunya 2007[62]

- Member of the World Knowledge Dialogue[63] Honorary Board, and Scientist in Residence for the 2008 symposium organized in Crans-Montana (Switzerland).

- Distinguished Lecturer, University of Iowa, 2008–2009

- E.O. Wilson Biophilia Center[64] on Nokuse Plantation in Walton County, Florida 2009 video[65]

- Explorers Club Medal, 2009

- 2010 BBVA Frontiers of Knowledge Award in the Ecology and Conservation Biology Category[66]

- Thomas Jefferson Medal in Architecture, 2010

- 2010 Heartland Prize for fiction for his first novel Anthill: A Novel[67]

- EarthSky Science Communicator of the Year, 2010

- International Cosmos Prize, 2012[68]

- Kew International Medal (2014)[1]

Main works

- Brown, W. L.; Wilson, E. O. (1956). "Character displacement". Systematic Zoology. 5 (2): 49–64. doi:10.2307/2411924. JSTOR 2411924., coauthored with William Brown Jr.; paper honored in 1986 as a Science Citation Classic, i.e., as one of the most frequently cited scientific papers of all time.[69]

- The Theory of Island Biogeography, 1967, Princeton University Press (2001 reprint), ISBN 0-691-08836-5, with Robert H. MacArthur

- The Insect Societies, 1971, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-45490-1

- Sociobiology: The New Synthesis 1975, Harvard University Press, (Twenty-fifth Anniversary Edition, 2000 ISBN 0-674-00089-7)

- On Human Nature, 1979, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-01638-6, winner of the 1979 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.

- Genes, Mind and Culture: The Coevolutionary Process, 1981, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-34475-8

- Promethean Fire: Reflections on the Origin of Mind, 1983, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-71445-8

- Biophilia, 1984, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-07441-6

- Success and Dominance in Ecosystems: The Case of the Social Insects, 1990, Inter-Research, ISSN 0932-2205

- The Ants, 1990, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-04075-9, Winner of the 1991 Pulitzer Prize, with Bert Hölldobler

- The Diversity of Life, 1992, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-21298-3, The Diversity of Life: Special Edition, ISBN 0-674-21299-1

- The Biophilia Hypothesis, 1993, Shearwater Books, ISBN 1-55963-148-1, with Stephen R. Kellert

- Journey to the Ants: A Story of Scientific Exploration, 1994, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-48525-4, with Bert Hölldobler

- Naturalist, 1994, Shearwater Books, ISBN 1-55963-288-7

- In Search of Nature, 1996, Shearwater Books, ISBN 1-55963-215-1, with Laura Simonds Southworth

- Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, 1998, Knopf, ISBN 0-679-45077-7

- The Future of Life, 2002, Knopf, ISBN 0-679-45078-5

- Pheidole in the New World: A Dominant, Hyperdiverse Ant Genus, 2003, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-00293-8

- The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth, September 2006, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-06217-5

- Nature Revealed: Selected Writings 1949–2006, ISBN 0-8018-8329-6

- The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies, 2009, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-06704-0, with Bert Hölldobler

- Anthill: A Novel, April 2010, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-07119-1

- Kingdom of Ants: Jose Celestino Mutis and the Dawn of Natural History in the New World, 2010, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, with José María Gómez Durán

- The Leafcutter Ants: Civilization by Instinct, 2011, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-33868-3, with Bert Hölldobler

- The Social Conquest of Earth, 2012, Liveright Publishing Corporation, New York, ISBN 0871403633

- Letters to a Young Scientist, 2014, Liveright, ISBN 0871403854

- A Window on Eternity: A Biologist's Walk Through Gorongosa National Park, 2014, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 1476747415

- The Meaning of Human Existence, 2014, Liveright, ISBN 0871401002

- Half-Earth, 2016, Liveright, ISBN 978-1-63149-082-8

- The Origins of Creativity, 2017, Liveright, ISBN 978-1-63149-318-8

- Genesis: The Deep Origin of Societies, 2019, Liveright; ISBN 1-63149-554-2

- Tales from the Ant World, 2020, Liveright, ISBN 9781631495564[70]

Edited works

- From So Simple a Beginning: Darwin's Four Great Books, edited with introductions by Edward O. Wilson (2010 W.W. Norton)

In popular culture

Wilson was quoted in the opening lines of the Bliss n Eso song, "Weightless Wings", as follows: "A wise man once said we exist in a bizarre combination of stone age emotions, medieval beliefs, god-like technology many people can reach."

References

- "Ethiopia's Prof. Sebsebe Demissew awarded prestigious Kew International Medal – Kew". www.kew.org. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2018.

- Lenfield, Spencer. "Ants through the Ages". Harvard Magazine.

Wheeler's work strongly influenced the teenage Wilson, who recalls, "When I was 16 and decided I wanted to become a myrmecologist, I memorized his book."

- Thorpe, Vanessa (June 24, 2012). "Richard Dawkins in furious row with EO Wilson over theory of evolution". The Guardian. London.

- "Lord of the Ants documentary". VICE. 2009. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- Becker, Michael (April 9, 2009). "MSU presents Presidential Medal to famed scientist Edward O. Wilson". MSU News. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- Novacek, Michael J. (2001). "Lifetime achievement: E.O. Wilson". CNN.com. Archived from the original on October 14, 2006. Retrieved November 8, 2006.

- "E.O. Wilson advocates biodiversity preservation". Duke Chronicle. February 12, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- "Natural Connections > EDWARD WILSON BIO". Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- "E. O. Wilson biography". AlabamaLiteraryMap.org. Archived from the original on December 8, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- Cowles, Gregory. "Print & E-Books". The New York Times.

- Wilson, Edward O. (2006). Naturalist. Washington, D.C.: Island Press [for] Shearwater Books. ISBN 1597260886. OCLC 69669557.

- first-hand account, Smithsonian Institution talk, April 22, 2010

- "Edward O. Wilson Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- Levallois, Clement (September 19, 2018). "The Development of Sociobiology in Relation to Animal Behavior Studies, 1946–1975". Journal of the History of Biology. 51 (3): 419–444. doi:10.1007/s10739-017-9491-x. PMID 28986758.

- "'Father of sociobiology' to teach at Nicholas School". Post Retirement. Duke University. December 2013.

- E. O. Wilson, Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, New York, Knopf, 1998.

- Wolfe, Tom (1996). Sorry, But Your Soul Just Died. Vol. 158, Issue 13, Forbes

- "Discover Interview: E.O. Wilson". DiscoverMagazine.com. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- Rensberger, Boyce (November 9, 1975). "The Basic Elements of the Arguments Are Not New". The New York Times.

- Restak, Richard M. (April 24, 1983). "Is Our Culture In Our Genes?". The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- Wilson, E. O. Sociobiology. Harvard. Chapter 27.

- Grafen, Alan; Ridley, Mark (2006). Richard Dawkins: How a Scientist Changed the Way We Think. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-19-929116-0.

- Allen, Elizabeth, et al. (1975). "Against 'Sociobiology'". [letter] New York Review of Books 22 (Nov. 13): 182, 184–186.

- Wilson, Eward O.. Naturalist, Washington, DC: Island Press; (April 24, 2006), ISBN 1-59726-088-6

- French, Howard (November 2011). "E. O. Wilson's Theory of Everything". The Atlantic Magazine. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- Sahlins, Marshall David (1976). The Use and Abuse of Biology. ISBN 0-472-08777-0.

- Douglas, Ed (February 17, 2001). "Darwin's natural heir". The Guardian. London.

- Wilson, Edward O. (1995). Naturalist. ISBN 0-446-67199-1.

- David Dugan (writer, producer, director) (May 2008). Lord of the Ants (Documentary). NOVA. Retrieved January 25, 2008.

- Mythology of Scientific Materialism. Paul E. Rothrock and Mary Ellen Rothrock, PSCF 39 (June 1987): 87–93

- Midgley, Mary (1995). Beast and man : the roots of human nature (Rev. ed.). London [u.a.]: Routledge. p. xli. ISBN 0-415-12740-8.

- Midgley, Mary (1995). Beast and man: the roots of human nature (Rev. ed.). London [u.a.]: Routledge. p. xl. ISBN 0-415-12740-8.

- Haidt 2012, p. 37-38.

- Connie Barlow. "The Epic of Evolution: Religious and cultural interpretations of modern scientific cosmology". Science & Spirit Magazine. Archived from the original on May 23, 2006.

- Walsh, Bryan (August 17, 2011). "All-TIME 100 Nonfiction Books". Time. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- Nicholas Wade (July 15, 2008). "Taking a Cue From Ants on Evolution of Humans". The New York Times.

- Wade, Nicholas (May 12, 1998). "Scientist at Work: Edward O. Wilson; From Ants to Ethics: A Biologist Dreams Of Unity of Knowledge". The New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- Wilson, Edward O. (March 27, 1997). "Karl Marx was right, socialism works" (Interview). Harvard University.

- Wilson, Edward O. (November 1, 2005). "Intelligent Evolution". Harvard Magazine. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- "Notable Signers". Humanism and Its Aspirations. American Humanist Association. Retrieved October 6, 2012.

- The Creation

- Sarchet, Penny (February 1, 2015). "Why Do We Ignore Warnings About Earth's Future?". Slate.

In fact, I'm not an atheist ... I would even say I'm agnostic

- Human Nature

- Naturalist E.O. Wilson is optimistic Archived March 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Harvard Gazette June 15, 2006

- Scientist says there is hope to save planet Archived January 29, 2013, at Archive.today mywesttexas.com, September 18, 2009

- "Famed biologist: Religion 'is dragging us down' and must be eliminated 'for the sake of human progress'". Rawstory.com. January 28, 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- Penny Sarchet (January 21, 2015). "E. O. Wilson: Religious faith is dragging us down". New Scientist. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- Edward O. Wilson (2008). Lord of the Ants (documentary film) (television). NOVA/WGBH. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- Wilson, Edward Osborne (April 28, 1998). "Slide show". saveamericasforests.org. p. 2. Retrieved November 13, 2008.

- "Congress – The Act to Save America's Forests". Saveamericasforests.org. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- "The Forests NOW Declaration | Global Canopy Programme". globalcanopy.org. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- "Can the World Really Set Aside Half of the Planet for Wildlife? | Science | Smithsonian". Smithsonianmag.com. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- "Edward O. Wilson". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "Edward Wilson". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "The Four Awards Bestowed by The Academy of Natural Sciences and Their Recipients". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 156 (1): 403–404. June 2007. doi:10.1635/0097-3157(2007)156[403:TFABBT]2.0.CO;2.

- "Legendary Biologist and Pulitzer Prize Winner E.O. Wilson Visits UA as Scholar-in-Residence – Arts & Sciences". www.as.ua.edu.

- "Honorary doctorates – Uppsala University, Sweden". www.uu.se.

- "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- "Crafoord Prize". www.crafoordprize.se.

- "Benjamin Franklin Medal for Distinguished Achievement in the Sciences Recipients". American Philosophical Society. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- Archived November 11, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Previous winners". Ministry of the Presidency. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- "World Knowledge Dialogue". wkdialogue.ch.

- "biophilia-center". Eowilsoncenter.org. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- "E.O. Wilson Biophilia Center". Vimeo.

- "BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Awards". fbbva.es. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- "Chicago Humanities Festival". chicagohumanities.org.

- "The Prizewinner 2012". Expo '90 Foundation. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- "William L Brown, Jr. Obituary". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

- Wilson, Edward O.,. Tales from the ant world (First ed.). New York, N.Y. ISBN 978-1-63149-556-4. OCLC 1120085214.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: E. O. Wilson |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to E. O. Wilson. |

- Curriculum vitae

- E.O. Wilson Foundation

- Dawkins, Richard (May 24, 2012). "The Descent of Edward Wilson". Prospect. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Review of The Social Conquest of Earth

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- E. O. Wilson at TED