Boarding school

A boarding school provides education for pupils who live on the premises, as opposed to a day school. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. As they have existed for many centuries, and now extend across many countries, their function and ethos varies greatly. Traditionally, pupils stayed at the school for the length of the term; some schools facilitate returning home every weekend, and some welcome day pupils. Some are for either boys or girls while others are co-educational.

In the United Kingdom, which has a more extensive history of such schools, many independent (private) schools offer boarding, but likewise so do a few dozen state schools, many of which serve children from remote areas. In the United States, most boarding schools cover grades seven or nine through grade twelve—the high school years. Some American boarding schools offer a post-graduate year of study to help students prepare for college entrance.

In some times and places boarding schools are the most elite educational option (such as Eton and Harrow, which have produced several prime ministers), whereas in other contexts, they serve as places to segregate children deemed a problem to their parents or wider society. Canada and the United States tried to assimilate indigenous children in the Canadian Indian residential school system and American Indian boarding schools respectively. Some function essentially as orphanages, e.g. the G.I. Rossolimo Boarding School Number 49 in Russia. Tens of millions of rural children are now educated at boarding schools in China. Therapeutic boarding schools offer treatment for psychological difficulties. Military academies provide strict discipline. Education for children with special needs has a long association with boarding; see, for example, Deaf education and Council of Schools and Services for the Blind. Some boarding schools offer an immersion into democratic education, such as Summerhill School. Others are determinedly international, such as the United World Colleges.

Description

Typical characteristics

The term boarding school often refers to classic British boarding schools and many boarding schools around the world are modeled on these.[1]

House system

A typical boarding school has several separate residential houses, either within the school grounds or in the surrounding area.

A number of senior teaching staff are appointed as housemasters, housemistresses, dorm parents, prefects, or residential advisors, each of whom takes quasi-parental responsibility (in loco parentis) for anywhere from 5 to 50 students resident in their house or dormitory at all times but particularly outside school hours. Each may be assisted in the domestic management of the house by a housekeeper often known in U.K. or Commonwealth countries as matron, and by a house tutor for academic matters, often providing staff of each gender. In the U.S., boarding schools often have a resident family that lives in the dorm, known as dorm parents. They often have janitorial staff for maintenance and housekeeping, but typically do not have tutors associated with an individual dorm. Nevertheless, older students are often less supervised by staff, and a system of monitors or prefects gives limited authority to senior students. Houses readily develop distinctive characters, and a healthy rivalry between houses is often encouraged in sport.

Houses or dorms usually include study-bedrooms or dormitories, a dining room or refectory where students take meals at fixed times, a library and possibly study carrels where students can do their homework. Houses may also have common rooms for television and relaxation and kitchens for snacks, and occasionally storage facilities for bicycles or other sports equipment. Some facilities may be shared between several houses or dorms.

In some schools, each house has students of all ages, in which case there is usually a prefect system, which gives older students some privileges and some responsibility for the welfare of the younger ones. In others, separate houses accommodate needs of different years or classes. In some schools, day students are assigned to a dorm or house for social activities and sports purposes.

Most school dormitories have an "in your room by" and a "lights out" time, depending on their age, when the students are required to prepare for bed, after which no talking is permitted. Such rules may be difficult to enforce; students may often try to break them, for example by using their laptop computers or going to another student's room to talk or play computer games. International students may take advantage of the time difference between countries (e.g. 7 hours between UK and China) to contact friends or family. Students sharing study rooms are less likely to disturb others and may be given more latitude.

Other facilities

As well as the usual academic facilities such as classrooms, halls, libraries and laboratories, boarding schools often provide a wide variety of facilities for extracurricular activities such as music rooms, gymnasiums, sports fields and school grounds, boats, squash courts, swimming pools, cinemas and theaters. A school chapel is often found on site. Day students often stay on after school to use these facilities. Many North American boarding schools are located in beautiful rural environments, and have a combination of architectural styles that vary from modern to hundreds of years old.

Food quality can vary from school to school, but most boarding schools offer diverse menu choices for many kinds of dietary restrictions and preferences. Some boarding schools have a dress code for specific meals like dinner or for specific days of the week. Students are generally free to eat with friends, teammates, as well as with faculty and coaches. Extra curricular activities groups, e.g. the French Club, may have meetings and meals together. The Dining Hall often serves a central place where lessons and learning can continue between students and teachers or other faculty mentors or coaches. Some schools welcome day students to attend breakfast and dinner, in additional to the standard lunch, while others charge a fee.

Many boarding schools have an on-campus school store or snack hall where additional food and school supplies can be purchased; and may also have a student recreational center where food can be purchased during specified hours.

Time

Students generally need permission to go outside defined school bounds; they may be allowed to travel off-campus at certain times.

Depending on country and context, boarding schools generally offer one or more options: full (students stay at the school full-time), weekly (students stay in the school from Monday through Friday, then return home for the weekend), or on a flexible schedule (students choose when to board, e.g. during exam week).

Each student has an individual timetable, which in the early years allows little discretion.[2] Boarders and day students are taught together in school hours and in most cases continue beyond the school day to include sports, clubs and societies, or excursions.

British boarding schools have three terms a year, approximately twelve weeks each, with a few days' half-term holiday during which students are expected to go home or at least away from school. There may be several exeats, or weekends, in each half of the term when students may go home or away (e.g. international students may stay with their appointed guardians, or with a host family). Boarding students nowadays often go to school within easy traveling distance of their homes, and so may see their families frequently; e.g. families are encouraged to come and support school sports teams playing at home against other schools, or for school performances in music, drama or theatre.

Some boarding schools allow only boarding students, while others have both boarding students and day students who go home at the end of the school day. Day students are sometimes known as day boys or day girls. Some schools welcome day students to attend breakfast and dinner, while others charge a fee. For schools that have designated study hours or quiet hours in the evenings, students on campus (including day students) are usually required to observe the same "quiet" rules (such as no television, students must stay in their rooms, library or study hall, etc.). Schools that have both boarding and day students sometimes describe themselves as semi-boarding schools or day boarding schools. Some schools also have students who board during the week but go home on weekends: these are known as weekly boarders, quasi-boarders, or five-day boarders.

Other forms of residential schools

Boarding schools are residential schools; however, not all residential schools are "classic" boarding schools. Other forms of residential schools include:

- Therapeutic boarding schools are tuition-based, out-of-home placements that combine therapy and education for children, usually teenagers, with emotional, behavioral, substance abuse or learning disabilities.[3]

- Traveling boarding schools, such as Think Global School, are four-year high schools that immerse the students in a new city each term. Traveling boarding schools partner with a host school within the city to provide the living and educational facilities.[4]

- Sailing boarding schools, such as A+ World Academy, are high schools based on ships that sail around the world and combine high school education with travel, and personal development. Classes typically take place both, on board and in some of the ports they visit.[5]

- Outdoor boarding schools, which teach students independence and self-reliance through survival style camp outs and other outdoor activities.[6]

- Residential education programs, which provide a stable and supportive environment for at-risk children to live and learn together.

- Residential schools for students with special educational needs, who may or may not be disabled

- Semester schools, which complement a student's secondary education by providing a one semester residential experience with a central focusing curricular theme—which may appeal to students and families uninterested in a longer residential education experience

- Specialist schools focused on a particular academic discipline, such as the public North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics or the private Interlochen Arts Academy.

- The Israeli youth villages, where children stay and are educated in a commune, but also have everyday contact with their parents at specified hours.

- Public boarding schools, which are operated by public school districts. In the U.S., general-attendance public boarding schools were once numerous in rural areas, but are extremely rare today. As of the 2013–2014 school year, the SEED Foundation administered public charter boarding schools in Washington, D.C. and Baltimore, Maryland. One rural public boarding school is Crane Union High School in Crane, Oregon. Around two-thirds of its more than 80 students, mostly children from remote ranches, board during the school week in order to save a one-way commute of up to 150 miles (240 km) across Harney County.[7]

- Ranch school, once common in the western United States, incorporating aspects of the "dude ranch" (Guest ranch)

Applicable regulations

In the UK, almost all boarding schools are independent schools, which are not subject to the national curriculum or other educational regulations applicable to state schools. Nevertheless, there are some regulations, primarily for health and safety purposes, as well as the general law. The Department for Children, Schools and Families, in conjunction with the Department of Health of the United Kingdom, has prescribed guidelines for boarding schools, called the National Boarding Standards.[8]

One example of regulations covered within the National Boarding Standards are those for the minimum floor area or living space required for each student and other aspects of basic facilities. The minimum floor area of a dormitory accommodating two or more students is defined as the number of students sleeping in the dormitory multiplied by 4.2 m², plus 1.2 m². A minimum distance of 0.9 m should also be maintained between any two beds in a dormitory, bedroom or cubicle. In case students are provided with a cubicle, then each student must be provided with a window and a floor area of 5.0 m² at the least. A bedroom for a single student should be at least of floor area of 6.0 m². Boarding schools must provide a total floor area of at least 2.3 m² living accommodation for every boarder. This should also be incorporated with at least one bathtub or shower for every ten students.

These are some of the few guidelines set by the department among many others. It could probably be observed that not all boarding schools around the world meet these minimum basic standards, despite their apparent appeal.

History

Boarding schools manifest themselves in different ways in different societies. For example, in some societies children enter at an earlier age than in others. In some societies, a tradition has developed in which families send their children to the same boarding school for generations. One observation that appears to apply globally is that a significantly larger number of boys than girls attend boarding school and for a longer span of time. The practice of sending children, particularly boys, to other families or to schools so that they could learn together is of very long standing, recorded in classical literature and in UK records going back over 1,000 years.

In Europe, a practice developed by early medieval times of sending boys to be taught by literate clergymen, either in monasteries or as pages in great households. The King's School, Canterbury, arguably the world's oldest boarding school, dates its foundation from the development of the monastery school in around 597 AD. The author of the Croyland Chronicle recalls being tested on his grammar by Edward the Confessor's wife Queen Editha in the abbey cloisters as a Westminster schoolboy, in around the 1050s. Monastic schools as such were generally dissolved with the monasteries themselves under Henry VIII, although Westminster School was specifically preserved by the King's letters patent, and it seems likely that most schools were immediately replaced. Winchester College founded by Bishop William of Wykeham in 1382 and Oswestry School founded by David Holbache in 1407 are the oldest boarding schools in continuous operation.

United Kingdom

Boarding schools in Britain started in medieval times, when boys were sent to be educated at a monastery or noble household, where a lone literate cleric could be found. In the 12th century, the Pope ordered all Benedictine monasteries such as Westminster to provide charity schools, and many public schools started when such schools attracted paying students. These public schools reflected the collegiate universities of Oxford and Cambridge, as in many ways they still do, and were accordingly staffed almost entirely by clergymen until the 19th century. Private tuition at home remained the norm for aristocratic families, and for girls in particular, but after the 16th century it was increasingly accepted that adolescents of any rank might best be educated collectively. The institution has thus adapted itself to changing social circumstances over 1,000 years.

Boarding preparatory schools tend to reflect the public schools they feed. They often have a more or less official tie to particular schools.

The classic British boarding school became highly popular during the colonial expansion of the British Empire. British colonial administrators abroad could ensure that their children were brought up in British culture at public schools at home in the UK, and local rulers were offered the same education for their sons. More junior expatriates would send their children to local British-run schools, which would also admit selected local children who might travel from considerable distances. The boarding schools, which inculcated their own values, became an effective way to encourage local people to share British ideals, and so help the British achieve their imperial goals.

One of the reasons sometimes stated for sending children to boarding schools is to develop wider horizons than their family can provide. A boarding school a family has attended for generations may define the culture parents aspire to for their children. Equally, by choosing a fashionable boarding school, parents may aspire to better their children by enabling them to mix on equal terms with children of the upper classes. However, such stated reasons may conceal other reasons for sending a child away from home.[9][10][11] These might apply to children who are considered too disobedient or underachieving, children from families with divorced spouses, and children to whom the parents do not much relate.[10][11] These reasons are rarely explicitly stated, though the child might be aware of them.[10][11]

In 1998, there were 772 private-sector boarding schools in the United Kingdom with over 100,000 children attending them all across the country. In Britain, they are an important factor in the class system. About one percent of British children are sent to boarding schools.[12][13][14] Also in Britain children as young as 5 to 9 years of age are sent to boarding schools.[15]

United States

In the United States, boarding schools for students below the age of 13 are called junior boarding schools, and are relatively uncommon. The oldest junior boarding school is the Fay School in Southborough, Massachusetts, established in 1866. Other boarding schools are intended for high school age students, generally of ages 14–18. Some of the oldest of these boarding schools include West Nottingham Academy (est. 1744), Linden Hall (school) (est. 1756), The Governor's Academy (est. 1763), Phillips Academy Andover (est. 1778), and Phillips Exeter Academy (est. 1781).[16] Boarding schools for this age group are often referred to as prep schools. About half of one percent or (.5%) of school children attend boarding schools, about half the percentage of British children.[12][13][14]

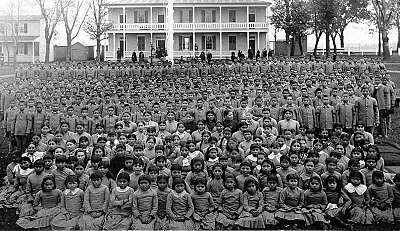

Native American schools

In the late 19th century, the United States government undertook a policy of educating Native American youth in the ways of the dominant Western culture so that Native Americans might then be able to assimilate into Western society. At these boarding schools, managed and regulated by the government, Native American students were subjected to a number of tactics to prepare them for life outside their reservation homes.[17]

In accordance with the assimilation methods used at the boarding schools, the education that the Native American children received at these institutions centered on the dominant society's construction of gender norms and ideals. Thus boys and girls were separated in almost every activity and their interactions were strictly regulated along the lines of Victorian ideals. In addition, the instruction that the children received reflected the roles and duties that they were to assume once outside the reservation. Thus girls were taught skills that could be used in the home, such as "sewing, cooking, canning, ironing, child care, and cleaning"[17] (Adams 150). Native American boys in the boarding schools were taught the importance of an agricultural lifestyle, with an emphasis on raising livestock and agricultural skills like "plowing and planting, field irrigation, the care of stock, and the maintenance of fruit orchards"[17] (Adams 149). These ideas of domesticity were in stark contrast to those existing in native communities and on reservations: many indigenous societies were based on a matrilineal system where the women's lineage was honored and the women's place in society respected. For example, women in native society held powerful roles in their own communities, undertaking tasks that Western society deemed only appropriate for men: indigenous women could be leaders, healers, and farmers.

While the Native American children were exposed to and were likely to adopt some of the ideals set out by the whites operating these boarding schools, many resisted and rejected the gender norms that were being imposed upon them. See also: Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Other Commonwealth countries

Most societies around the world decline to make boarding schools the preferred option for the upbringing of their children. However, boarding schools are one of the preferred modes of education in former British colonies or Commonwealth countries like India, Pakistan, Nigeria, and other former African colonies of Great Britain. For instance in Ghana the majority of the secondary schools are boarding. In China some children are sent to boarding schools at 2 years of age.[18] In some countries, such as New Zealand and Sri Lanka, a number of state schools have boarding facilities. These state boarding schools are frequently the traditional single-sex state schools, whose ethos is much like that of their independent counterparts. Furthermore, the proportion of boarders at these schools is often much lower than at independent boarding schools, typically around 10%.

Canada

In Canada, the largest independent boarding school is Columbia International College, with an enrollment of 1,700 students from all over the world. Robert Land Academy in Wellandport, Ontario is Canada's only private military style boarding school for boys in Grades 6 through 12.

Russia and former Soviet Union

In the former Soviet Union these schools were sometimes known as Internat-schools (Russian: Школа-интернат) (from Latin: internus). They varied in their organization. Some schools were a type of specialized school with a specific focus in a particular field or fields such as mathematics, physics, language, science, sports, etc. Other schools were associated with orphanages after which all children enrolled in Internat-school automatically. Also, separate boarding schools were established for children with special needs (schools for blind, for deaf and other). General schools offered "extended stay" programs (Russian: Группа продленного дня) featuring cheap meals for children and preventing them from coming home too early before parents were back from work (education in the Soviet Union was free). In post-Soviet countries, the concept of boarding school differs from country to country.

Switzerland

The Swiss government developed a strategy of fostering private boarding schools for foreign students as a business integral to the country's economy. Their boarding schools offer instruction in several major languages and have a large number of quality facilities organized through the Swiss Federation of Private Schools. In 2015, a Swiss boarding school named A+ World Academy was established on the Norwegian Tall Ship Fullriggeren Sørlandet. The top four most expensive boarding schools in the world are the Swiss schools Institut Le Rosey,[19] Beau Soleil, Collège du Léman and Collège Champittet.

China

As of 2015 there were about 100,000 boarding schools in rural areas of Mainland China, with about 33 million children living in them.[20] The majority of these boarding schools are in western China, which generally is not as wealthy as eastern and central China.[21] Many migrant workers and farmers send their children to boarding schools.[22]

Sociological issues

Some elite university-preparatory boarding schools for students from age 13 to 18 are seen by sociologists as centers of socialization for the next generation of the political upper class and reproduces an elitist class system.[23] This attracts families who value power and hierarchy for the socialization of their family members.[23] These families share a sense of entitlement to social class or hierarchy and power.[23]

Boarding schools are seen by certain families as centres of socialization where students mingle with others of similar social hierarchy[23] to form what is called an old boy network. Elite boarding school students are brought up with the assumption that they are meant to control society.[23] Significant numbers of them enter the political upper class of society or join the financial elite in fields such as international banking and venture capital.[23] Elite boarding school socialization causes students to internalize a strong sense of entitlement and social control or hierarchy.[23] This form of socialization is called "deep structure socialization" by Peter Cookson & Caroline Hodges (1985).[23][24] This refers to the way in which boarding schools not only manage to control the students' physical lives but also their emotional lives.[23][24]

Boarding school establishment involves control of behaviour regarding several aspects of life including what is appropriate and/or acceptable which adolescents would consider as intrusive.[23][24] This boarding school socialization is carried over well after leaving school and into their dealings with the social world.[23] Thus it causes boarding school students to adhere to the values of the elite social class which they come from or which they aspire to be part of.[23] Nick Duffell, author of Wounded Leaders: British elitism and the Entitlement Illusion – A Psychohistory, states that the education of the elite in the British boarding school system leaves the nation with "a cadre of leaders who perpetuate a culture of elitism, bullying and misogyny affecting the whole of society".[25] According to Peter W Cookson Jr (2009) the elitist tradition of preparatory boarding schools has declined due to the development of modern economy and the political rise of the liberal west coast of the United States of America.[23][24] Further, as of 2017, there are over twenty boarding schools on the west coast of the United States.

Socialization of role control and gender stratification

The boarding school socialization of control and hierarchy develops deep rooted and strong adherence to social roles and rigid gender stratification.[23][26] In one studied school the social pressure for conformity was so severe that several students abused performance drugs like Adderall and Ritalin for both academic performance and to lose weight.[23][26] The distinct and hierarchical nature of socialization in boarding school culture becomes very obvious in the manner students sit together and form cliques, especially in the refectory, or dining hall. This leads to pervasive form of explicit and implicit bullying, and excessive competition between cliques and between individuals.[23][26] The rigid gender stratification and role control is displayed in the boys forming cliques on the basis of wealth and social background, and the girls overtly accepting that they would marry only for money, while choosing only rich or affluent males as boyfriends.[23][26] Students are not able to display much sensitivity and emotional response and are unable to have closer relationships except on a superficial and politically correct level, engaging in social behaviour that would make them seem appropriate and rank high in social hierarchy.[23][26] This affects their perceptions of gender and social roles later in life.[23][26]

One alumnus of a military boarding school also questions whether leadership is truly being learned by the school's students.[27]

Psychological issues

The aspect of boarding school life with its round the clock habitation of students with each other in the same environment, involved in studying, sleeping and socializing can lead to pressures and stress in boarding school life.[23] This is manifested in the form of hypercompetitiveness, use of recreational or illegal drugs and psychological depression that at times may manifest in suicide or its attempt.[23] Studies show that about 90% of boarding school students acknowledge that living in a total institution like boarding school has significant impact and changed their perception and interaction with social relationships.[23]

Total institution and child displacement

It is claimed that children may be sent to boarding schools to give more opportunities than their family can provide. However, that involves spending significant parts of one's early life in what may be seen as a total institution[28] and possibly experiencing social detachment, as suggested by social-psychologist Erving Goffman.[28] This may involve long-term separation from one's parents and culture, leading to the experience of homesickness[29][30][31] and emotional abandonment[10][11][15] and may give rise to a phenomenon known as the 'TCK' or third culture kid.[32]

The celebrated British classicist and poet, Robert Graves (1895–1985), who attended six different preparatory schools at a young age during the early 20th century, wrote:

Preparatory schoolboys live in a world completely dissociated from home life. They have a different vocabulary, a different moral system, even different voices. On their return to school from the holidays the change-over from home-self to school-self is almost instantaneous, whereas the reverse process takes a fortnight at least. A preparatory schoolboy, when caught off his guard, will call his mother 'Please, matron,' and always addresses any male relative or friend of the family as 'Sir', like a master. I used to do it. School life becomes the reality, and home life the illusion. In England, parents of the governing classes virtually lose any intimate touch with their children from about the age of eight, and any attempts on their parts to insinuate home feeling into school life are resented.

— Robert Graves[33]

Some modern philosophies of education, such as constructivism and new methods of music training for children including Orff Schulwerk and the Suzuki method, make the everyday interaction of the child and parent an integral part of training and education. In children, separation involves maternal deprivation.[34] The European Union-Canada project "Child Welfare Across Borders" (2003),[9] an important international venture on child development, considers boarding schools as one form of permanent displacement of the child.[9] This view reflects a new outlook towards education and child growth in the wake of more scientific understanding of the human brain and cognitive development.

Data have not yet been tabulated regarding the statistical ratio of boys to girls that matriculate boarding schools, the total number of children in a given population in boarding schools by country, the average age across populations when children are sent to boarding schools, and the average length of education (in years) for boarding school students. There is also little evidence or research about the complete circumstances or complete set of reasons about sending kids to boarding schools.[14]

Boarding school syndrome

The term boarding school syndrome was coined by psychotherapist Joy Schaverien in 2011.[35] It is used to identify a set of lasting psychological problems that are observable in adults who, as children, were sent away to boarding schools at an early age.

Children sent away to school at an early age suffer the sudden and often irrevocable loss of their primary attachments; for many this constitutes a significant trauma. Bullying and sexual abuse, by staff or other children, may follow and so new attachment figures may become unsafe. In order to adapt to the system, a defensive and protective encapsulation of the self may be acquired; the true identity of the person then remains hidden. This pattern distorts intimate relationships and may continue into adult life. The significance of this may go unnoticed in psychotherapy. It is proposed that one reason for this may be that the transference and, especially the breaks in psychotherapy, replay, for the patient, the childhood experience between school and home. Observations from clinical practice are substantiated by published testimonies, including those from established psychoanalysts who were themselves early boarders.[35]

Scharverien's observations are echoed by boarding school boy, George Monbiot, who goes so far as to attribute some dysfunctionalities of the UK government to boarding schools.[36]

In popular culture

Books

Boarding schools and their surrounding settings and situations became in the late Victorian period a genre in British literature with its own identifiable conventions. (Typically, protagonists find themselves occasionally having to break school rules for honourable reasons the reader can identify with, and might get severely punished when caught – but usually they do not embark on a total rebellion against the school as a system.)

Notable examples of the school story include:

- Sarah Fielding's The Governess, or The Little Female Academy (1749)

- Charles Dickens's serialised novel Nicholas Nickleby (1838)

- Charlotte Brontë's novels Jane Eyre (1847) and Villette (1853)

- Thomas Hughes's novel Tom Brown's Schooldays (1857)

- Frederic W. Farrar's Eric, or, Little by Little (1858), a particularly religious and moralistic treatment of the theme

- L. T. Meade's A World of Girls (1886) and dozens more girls school stories

- O Ateneu (1888), written by the Brazilian Raul Pompéia and dealing openly with the issue of homosexuality in the boarding school

- Frances Hodgson Burnett's serial Sara Crewe: or what Happened at Miss Minchin's (1887), revised and expanded as A Little Princess (1905)

- Greyfriars School, created by Charles Hamilton (wrting as Frank Richards) in 1910 in the first of what became 1,670 stories, many featuring Billy Bunter.

- George Orwell's essay Boys' Weeklies suggested in 1940 that Frank Richards created a taste for public schools stories in readers who could never have attended public schools

- Boy by Roald Dahl

- Dozens of boys' school novels by Gunby Hadath (1871–1954)

- Elinor Brent-Dyer's Chalet School series of about sixty children's novels (1925–1970)

- Erich Kästner's The Flying Classroom (Das Fliegende Klassenzimmer) (1933) is a conspicuous non-British example.

- James Hilton's novel Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1934) centers on a teacher, rather than on the students

- Ludwig Bemelmans' Madeline series of children's picture books (1939–present)

- Muriel Spark's The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961)

- Penelope Farmer's Charlotte Sometimes (1969)

- In Jill Murphy's The Worst Witch stories (from 1974), the traditional boarding school themes are explored in a fantasy school that teaches magic.

- Dianna Wynne Jones's novel Witch Week (1982) features Larwood House where magic is not taught —its use is a capital crime— but many students grow into magic powers

- J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series (1997–2007) features Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry

- Jenny Nimmo's Children of the Red King series (2002–2009) features magically endowed children at Bloor Academy, which most students leave on weekends

- Libba Bray's Gemma Doyle Trilogy, volumes one and two (2003, 2006), features a girl's discovery of magical capabilities and realms

- Enid Blyton's Malory Towers, St Clare's and Naughtiest Girl series

- John van de Ruit's Spud book and movie series, that take place at a school based on Michaelhouse

The setting has also been featured in notable North American fiction:

- J.D. Salinger's novel The Catcher in the Rye (1951)

- John Knowles's novels A Separate Peace (1959) and Peace Breaks Out (1981)

- Edward Kay's science fiction novel STAR Academy (2009)

- John Green's 2006 young adult novel Looking for Alaska

There is also a huge boarding-school genre literature, mostly uncollected, in British comics and serials from the 1900s to the 1980s.

The subgenre of books and films set in a military or naval academy has many similarities with the above.

Films and television

- Mädchen in Uniform (1931)

- Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939)

- Tom Brown's Schooldays (1940)

- The Browning Version (1951)

- Tom Brown's Schooldays (1951)

- "St Trinian's quartet" (1954–1966) original film series

- Hasta el viento tiene miedo (1968)

- If.... (1968)

- The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969)

- Pink Floyd – The Wall (1982)

- Class (1983)

- Another Country (1984)

- Dead Poets Society (1989)

- The Power of One (1992)

- Scent of a Woman (1992)

- The Browning Version (1994)

- A Little Princess (1995)

- Boys (1996)

- Ponette (1996) (French Film)

- Madeline (1998)

- Harry Potter series, Hogwarts (2001–2011)

- Cadet Kelly (2002)

- Rebelde Way (2002–2004)

- Strange Days at Blake Holsey High (2002–2006)

- Les Choristes (2004)

- St. Trinian's (2007)

- Zoey 101

- She's the Man (2006)

- Young Americans

- Wild Child (2008)

- Hanazakarino Kimitachihe (2006)

- Hanazakari no Kimitachi e (2007)

- Hanazakari no Kimitachi e (2011 TV series) (2011)

- To The Beautiful You (2012)

- Lost and Delirious (2001)

- Archer (2009–present)

- Cracks (2009)

- St Trinian's 2: The Legend of Fritton's Gold (2009)

- Loving Annabelle (2006)

- The Moth Diaries (2011)

- 5ive Girls (2006)

- Barbie: Princess Charm School (2011)

- Prom Wars (2008)

- The Trouble with Angels (1966)

- The Facts of Life

- You Are Not Alone (1978)

- House of Anubis (2011–2013)

- Ever After High (2013–present)

- Descendants (2015 film) (2015–present)

- Taps (1981)

- Candy Candy (1976)

Video games

- Final Fantasy VIII (1998)

- Bully (2006)

- Katawa Shoujo (2012)

- Life Is Strange (2015)

- Fire Emblem: Three Houses (2019)

See also

- List of boarding schools

- Special school

References

- Bamford T.W. (1967) Rise of the public schools: a study of boys public boarding schools in England and wales from 1837 to the present day. London : Nelson, 1967.

- Linton Hall Cadet, Linton Hall Military School Memories: One cadet's memoir, Arlington, VA.: Scrounge Press, 2014 ISBN 978-1-4959-3196-3

- Story, Louise (17 August 2005), "A Business Built on the Troubles of Teenagers", The New York Times

- "What is TGS?". Think Global School. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- "What is TGS?".

- "Wilderness Therapy Program, Therapeutic Boarding School for Troubled Boys". Woodcreek Academy. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- "The Oregon Story . Rural Voices: Three Days at Crane . Crane High School – OPB".

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2006. Retrieved 11 December 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- CWAB – Session 6.2 – Reasons for displacement Archived 20 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine European Union – Canada project Child welfare across borders (2003)

- Duffell, N. "The Making of Them. The British Attitude to Children and the Boarding School System". (London: Lone Arrow Press, 2000).

- Schaverien, J. (2004) Boarding School: The Trauma of the Privileged Child, in Journal of Analytical Psychology, vol 49, 683–705

- Dansokho, S., Little, M., & Thomas, B. (2003). Residential services for children: definitions, numbers and classifications. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children.

- Department of Health. (1998). Caring for Children away from Home. Chichester: Wiley and Son

- Little, M. Kohm, A. Thompson, R. (2005). "The impact of residential placement on child development: research and policy implications". International Journal of Social Welfare; 14, 200–209. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2397.2005.00360.x

- Power A (2007) "Discussion of Trauma at the Threshold: The Impact of Boarding School on Attachment in Young Children", in ATTACHMENT: New Directions in Psychotherapy and Relational Psychoanalysis; Vol. 1, November 2007: pp. 313–320

- "Boarding Schools with the Oldest Founding Date (2017–2018)". www.boardingschoolreview.com. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928. University of Kansas Press, Lawrence: 1995.

- Markus, Francis (10 June 2004). "Asia-Pacific | Private school for China's youngest". BBC News. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "The most expensive boarding school in the world". 28 January 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- Roberts, Dexter. "China's Dickensian Boarding Schools" (Archive). Bloomberg Businessweek. 6 April 2015. Retrieved on 13 July 2015.

- Zhao, Zhenzhou, p. 238

- Hatton, Celia. "Search for justice after China school abuse" (Archive). BBC. 6 April 2015. Retrieved on 13 July 2015.

- Cookson, Jr., Peter W.; Shweder, Richard A. (15 September 2009). "Boarding Schools". The Child: An Encyclopedic Companion. University of Chicago Press. pp. 112–114. ISBN 978-0-226-47539-4.

- Cookson, Jr., Peter W.; Hodges Persell, Caroline (30 September 1987). Preparing For Power: America's Elite Boarding Schools. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-06269-0.

- "Why boarding schools produce bad leaders". The Guardian. 9 June 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- Chase, Sarah A. (26 June 2008). Perfectly Prep: Gender Extremes at a New England Prep School. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530881-5.

- Hall, Linton (31 August 2011). "Linton Hall Military School alumni memories: Did we learn leadership at Linton Hall Military School?". Lintonhallmilitaryschool.blogspot.com. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Goffman, Erving (1961) Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. (New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1961); (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1968) ISBN 0-385-00016-2

- Brewin, C.R., Furnham, A. & Howes, M. (1989). Demographic and psychological determinants of homesickness and confiding among students. British Journal of Psychology, 80, 467–477.

- Fisher, S., Frazer, N. & Murray, K (1986). Homesickness and health in boarding school children. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 6, 35–47.

- Thurber A. Christopher (1999) The phenomenology of homesickness in boys, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology

- Pollock DC and Van Reken R (2001). Third Culture Kids. Nicholas Brealey Publishing/Intercultural Press. Yarmouth, Maine. ISBN 1-85788-295-4.

- Graves, Robert Goodbye to All That, chapter 3, page 24 Penguin Modern Classics 1967 edition

- Rutter, M (1972) Maternal Deprivation Reassessed. London:Penguin

- Schaverien, Joy (May 2011). "Boarding School Syndrome: Broken Attachments A Hidden Trauma". British Journal of Psychotherapy. 27 (2): 138–155. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0118.2011.01229.x. ISSN 0265-9883.

- Monbiot, George (11 November 2019). "The Unlearning". George Monbiot. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

Further reading

- Cadet, Linton Hall, Linton Hall Military School Memories: One cadet's memoir, Scrounge Press, 2014. ISBN 9781495931963 Memoir of cadet who attended during the late 1960s, with copies of brochures from the 1940s and 1980s, and photos of the school.

- Cookson, Peter W., Jr., and Caroline Hodges Persell. Preparing for Power: America's Elite Boarding Schools. (New York: Basic Books, 1985).

- Fisher, S. & Hood, B. (1987). The stress of the transition to university: a longitudinal study of psychological disturbance, absent-mindedness and vulnerability to homesickness. British Journal of Psychology, 78, 425–441

- Hein, David (1991). The High Church origins of the American boarding school. Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 42, 577–95.

- Hickson, A. "The Poisoned Bowl: Sex Repression and the Public School System". (London: Constable, 1995).

- Johann, Klaus: Grenze und Halt: Der Einzelne im "Haus der Regeln". Zur deutschsprachigen Internatsliteratur. (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter 2003, Beiträge zur neueren Literaturgeschichte, 201.), ISBN 3-8253-1599-1. Review

- Ladenthin, Volker; Fitzek, Herbert; Ley, Michael: Das Internat. Aufgaben, Erwartungen und Evaluationskriterien. Bonn 2006 (7. Aufl.).

- Duffel N. (2000) The making of them. London: Lone Arrow Press

- Schaverien, J. (2004) Boarding School: The Trauma of the Privileged Child, in Journal of Analytical Psychology, vol 49, 683–705 <https://web.archive.org/web/20060822135014/http://isana.org.au/_Upload/Files/2005112215407_Boardingschool%5B1%5D.pdf>

- Cookson, P. W., Jr. (2009). "Boarding Schools" in The Child: an encyclopedic companion (ed.) Richard A Shweder. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 112–114.