Programmed cell death

Programmed cell death (PCD; sometimes referred to as cellular suicide[1]) is the death of a cell as a result of events inside of a cell, such as apoptosis or autophagy.[2][3] PCD is carried out in a biological process, which usually confers advantage during an organism's life-cycle. For example, the differentiation of fingers and toes in a developing human embryo occurs because cells between the fingers apoptose; the result is that the digits are separate. PCD serves fundamental functions during both plant and animal tissue development.

Apoptosis and autophagy are both forms of programmed cell death.[4] Necrosis is the death of a cell caused by external factors such as trauma or infection and occurs in several different forms. Necrosis was long seen as a non-physiological process that occurs as a result of infection or injury,[4] but in the 2000s, a form of programmed necrosis, called necroptosis,[5] was recognized as an alternative form of programmed cell death. It is hypothesized that necroptosis can serve as a cell-death backup to apoptosis when the apoptosis signaling is blocked by endogenous or exogenous factors such as viruses or mutations. Most recently, other types of regulated necrosis have been discovered as well, which share several signaling events with necroptosis and apoptosis.[6]

History

The concept of "programmed cell-death" was used by Lockshin & Williams[7] in 1964 in relation to insect tissue development, around eight years before "apoptosis" was coined. Since then, PCD has become the more general of these two terms.

The first insight into the mechanism came from studying BCL2, the product of a putative oncogene activated by chromosome translocations often found in follicular lymphoma. Unlike other cancer genes, which promote cancer by stimulating cell proliferation, BCL2 promoted cancer by stopping lymphoma cells from being able to kill themselves.[8]

PCD has been the subject of increasing attention and research efforts. This trend has been highlighted with the award of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Sydney Brenner (United Kingdom), H. Robert Horvitz (US) and John E. Sulston (UK).[9]

Types

- Apoptosis or Type I cell-death.

- Autophagic or Type II cell-death. (Cytoplasmic: characterized by the formation of large vacuoles that eat away organelles in a specific sequence prior to the destruction of the nucleus.)[10]

Apoptosis

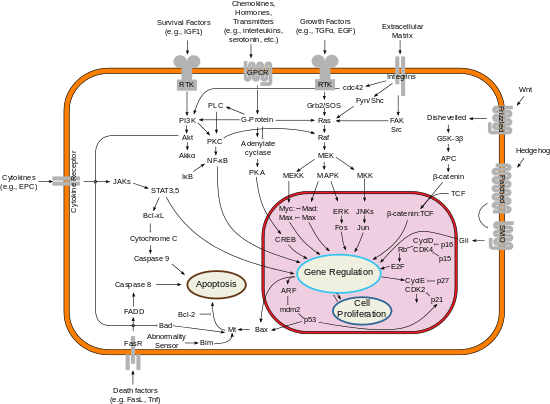

Apoptosis is the process of programmed cell death (PCD) that may occur in multicellular organisms.[11] Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (morphology) and death. These changes include blebbing, cell shrinkage, nuclear fragmentation, chromatin condensation, and chromosomal DNA fragmentation. It is now thought that- in a developmental context- cells are induced to positively commit suicide whilst in a homeostatic context; the absence of certain survival factors may provide the impetus for suicide. There appears to be some variation in the morphology and indeed the biochemistry of these suicide pathways; some treading the path of "apoptosis", others following a more generalized pathway to deletion, but both usually being genetically and synthetically motivated. There is some evidence that certain symptoms of "apoptosis" such as endonuclease activation can be spuriously induced without engaging a genetic cascade, however, presumably true apoptosis and programmed cell death must be genetically mediated. It is also becoming clear that mitosis and apoptosis are toggled or linked in some way and that the balance achieved depends on signals received from appropriate growth or survival factors.[12]

Autophagy

Macroautophagy, often referred to as autophagy, is a catabolic process that results in the autophagosomic-lysosomal degradation of bulk cytoplasmic contents, abnormal protein aggregates, and excess or damaged organelles.

Autophagy is generally activated by conditions of nutrient deprivation but has also been associated with physiological as well as pathological processes such as development, differentiation, neurodegenerative diseases, stress, infection and cancer.

Mechanism

A critical regulator of autophagy induction is the kinase mTOR, which when activated, suppresses autophagy and when not activated promotes it. Three related serine/threonine kinases, UNC-51-like kinase -1, -2, and -3 (ULK1, ULK2, UKL3), which play a similar role as the yeast Atg1, act downstream of the mTOR complex. ULK1 and ULK2 form a large complex with the mammalian homolog of an autophagy-related (Atg) gene product (mAtg13) and the scaffold protein FIP200. Class III PI3K complex, containing hVps34, Beclin-1, p150 and Atg14-like protein or ultraviolet irradiation resistance-associated gene (UVRAG), is required for the induction of autophagy.

The ATG genes control the autophagosome formation through ATG12-ATG5 and LC3-II (ATG8-II) complexes. ATG12 is conjugated to ATG5 in a ubiquitin-like reaction that requires ATG7 and ATG10. The Atg12–Atg5 conjugate then interacts non-covalently with ATG16 to form a large complex. LC3/ATG8 is cleaved at its C terminus by ATG4 protease to generate the cytosolic LC3-I. LC3-I is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) also in a ubiquitin-like reaction that requires Atg7 and Atg3. The lipidated form of LC3, known as LC3-II, is attached to the autophagosome membrane.

Autophagy and apoptosis are connected both positively and negatively, and extensive crosstalk exists between the two. During nutrient deficiency, autophagy functions as a pro-survival mechanism, however, excessive autophagy may lead to cell death, a process morphologically distinct from apoptosis. Several pro-apoptotic signals, such as TNF, TRAIL, and FADD, also induce autophagy. Additionally, Bcl-2 inhibits Beclin-1-dependent autophagy, thereby functioning both as a pro-survival and as an anti-autophagic regulator.

Other types

Besides the above two types of PCD, other pathways have been discovered.[13] Called "non-apoptotic programmed cell-death" (or "caspase-independent programmed cell-death" or "necroptosis"), these alternative routes to death are as efficient as apoptosis and can function as either backup mechanisms or the main type of PCD.

Other forms of programmed cell death include anoikis, almost identical to apoptosis except in its induction; cornification, a form of cell death exclusive to the eyes; excitotoxicity; ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of cell death[14] and Wallerian degeneration.

Necroptosis is a programmed form of necrosis, or inflammatory cell death. Conventionally, necrosis is associated with unprogrammed cell death resulting from cellular damage or infiltration by pathogens, in contrast to orderly, programmed cell death via apoptosis. Nemosis is another programmed form of necrosis that takes place in fibroblasts.[15]

Eryptosis is a form of suicidal erythrocyte death.[16]

Aponecrosis is a hybrid of apoptosis and necrosis and refers to an incomplete apoptotic process that is completed by necrosis.[17]

NETosis is the process of cell-death generated by NETs.[18]

Paraptosis is another type of nonapoptotic cell death that is mediated by MAPK through the activation of IGF-1. It's characterized by the intracellular formation of vacuoles and swelling of mitochondria.[19]

Pyroptosis, an inflammatory type of cell death, is uniquely mediated by caspase 1, an enzyme not involved in apoptosis, in response to infection by certain microorganisms.[19]

Plant cells undergo particular processes of PCD similar to autophagic cell death. However, some common features of PCD are highly conserved in both plants and metazoa.

Atrophic factors

An atrophic factor is a force that causes a cell to die. Only natural forces on the cell are considered to be atrophic factors, whereas, for example, agents of mechanical or chemical abuse or lysis of the cell are considered not to be atrophic factors. Common types of atrophic factors are:[20]

- Decreased workload

- Loss of innervation

- Diminished blood supply

- Inadequate nutrition

- Loss of endocrine stimulation

- Senility

- Compression

Role in the development of the nervous system

The initial expansion of the developing nervous system is counterbalanced by the removal of neurons and their processes.[21] During the development of the nervous system almost 50% of developing neurons are naturally removed by programmed cell death (PCD).[22] PCD in the nervous system was first recognized in 1896 by John Beard.[23] Since then several theories were proposed to understand its biological significance during neural development.[24]

Role in neural development

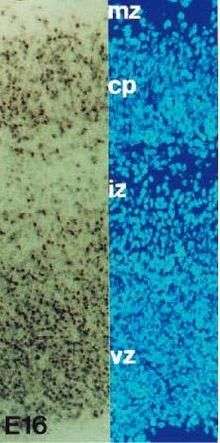

PCD in the developing nervous system has been observed in proliferating as well as post-mitotic cells.[21] One theory suggests that PCD is an adaptive mechanism to regulate the number of progenitor cells. In humans, PCD in progenitor cells starts at gestational week 7 and remains until the first trimester.[25] This process of cell death has been identified in the germinal areas of the cerebral cortex, cerebellum, thalamus, brainstem, and spinal cord among other regions.[24] At gestational weeks 19–23, PCD is observed in post-mitotic cells.[26] The prevailing theory explaining this observation is the neurotrophic theory which states that PCD is required to optimize the connection between neurons and their afferent inputs and efferent targets.[24] Another theory proposes that developmental PCD in the nervous system occurs in order to correct for errors in neurons that have migrated ectopically, innervated incorrect targets, or have axons that have gone awry during path finding.[27] It is possible that PCD during the development of the nervous system serves different functions determined by the developmental stage, cell type, and even species.[24]

The neurotrophic theory

The neurotrophic theory is the leading hypothesis used to explain the role of programmed cell death in the developing nervous system[28]. It postulates that in order to ensure optimal innervation of targets, a surplus of neurons is first produced which then compete for limited quantities of protective neurotrophic factors and only a fraction survive while others die by programmed cell death.[25] Furthermore, the theory states that predetermined factors regulate the amount of neurons that survive and the size of the innervating neuronal population directly correlates to the influence of their target field.[29]

The underlying idea that target cells secrete attractive or inducing factors and that their growth cones have a chemotactic sensitivity was first put forth by Santiago Ramon y Cajal in 1892.[30] Cajal presented the idea as an explanation for the “intelligent force” axons appear to take when finding their target but admitted that he had no empirical data.[30] The theory gained more attraction when experimental manipulation of axon targets yielded death of all innervating neurons. This developed the concept of target derived regulation which became the main tenet in the neurotrophic theory.[31][32] Experiments that further supported this theory led to the identification of the first neurotrophic factor, nerve growth factor (NGF).[33]

Peripheral versus central nervous system

Different mechanisms regulate PCD in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) versus the central nervous system (CNS). In the PNS, innervation of the target is proportional to the amount of the target-released neurotrophic factors NGF and NT3.[34][35] Expression of neurotrophin receptors, TrkA and TrkC, is sufficient to induce apoptosis in the absence of their ligands.[22] Therefore, it is speculated that PCD in the PNS is dependent on the release of neurotrophic factors and thus follows the concept of the neurotrophic theory.

Programmed cell death in the CNS is not dependent on external growth factors but instead relies on intrinsically derived cues. In the neocortex, a 4:1 ratio of excitatory to inhibitory interneurons is maintained by apoptotic machinery that appears to be independent of the environment.[35] Supporting evidence came from an experiment where interneuron progenitors were either transplanted into the mouse neocortex or cultured in vitro.[36] Transplanted cells died at the age of two weeks, the same age at which endogenous interneurons undergo apoptosis. Regardless of the size of the transplant, the fraction of cells undergoing apoptosis remained constant. Furthermore, disruption of TrkB, a receptor for brain derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf), did not affect cell death. It has also been shown that in mice null for the proapoptotic factor Bax (Bcl-2-associated X protein) a larger percentage of interneurons survived compared to wild type mice.[36] Together these findings indicate that programmed cell death in the CNS partly exploits Bax-mediated signaling and is independent of BDNF and the environment. Apoptotic mechanisms in the CNS are still not well understood, yet it is thought that apoptosis of interneurons is a self-autonomous process.

Nervous system development in its absence

Programmed cell death can be reduced or eliminated in the developing nervous system by the targeted deletion of pro-apoptotic genes or by the overexpression of anti-apoptotic genes. The absence or reduction of PCD can cause serious anatomical malformations but can also result in minimal consequences depending on the gene targeted, neuronal population, and stage of development.[24] Excess progenitor cell proliferation that leads to gross brain abnormalities is often lethal, as seen in caspase-3 or caspase-9 knockout mice which develop exencephaly in the forebrain.[37][38] The brainstem, spinal cord, and peripheral ganglia of these mice develop normally, however, suggesting that the involvement of caspases in PCD during development depends on the brain region and cell type.[39] Knockout or inhibition of apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (APAF1), also results in malformations and increased embryonic lethality.[40][41][42] Manipulation of apoptosis regulator proteins Bcl-2 and Bax (overexpression of Bcl-2 or deletion of Bax) produces an increase in the number of neurons in certain regions of the nervous system such as the retina, trigeminal nucleus, cerebellum, and spinal cord.[43][44][45][46][47][48][49] However, PCD of neurons due to Bax deletion or Bcl-2 overexpression does not result in prominent morphological or behavioral abnormalities in mice. For example, mice overexpressing Bcl-2 have generally normal motor skills and vision and only show impairment in complex behaviors such as learning and anxiety.[50][51][52] The normal behavioral phenotypes of these mice suggest that an adaptive mechanism may be involved to compensate for the excess neurons.[24]

Invertebrates and vertebrates

Learning about PCD in various species is essential in understanding the evolutionary basis and reason for apoptosis in development of the nervous system. During the development of the invertebrate nervous system, PCD plays different roles in different species[53]. The similarity of the asymmetric cell death mechanism in the nematode and the leech indicates that PCD may have an evolutionary significance in the development of the nervous system.[54] In the nematode, PCD occurs in the first hour of development leading to the elimination of 12% of non-gonadal cells including neuronal lineages.[55] Cell death in arthropods occurs first in the nervous system when ectoderm cells differentiate and one daughter cell becomes a neuroblast and the other undergoes apoptosis.[56] Furthermore, sex targeted cell death leads to different neuronal innervation of specific organs in males and females.[57] In Drosophila, PCD is essential in segmentation and specification during development.

In contrast to invertebrates, the mechanism of programmed cell death is found to be more conserved in vertebrates. Extensive studies performed on various vertebrates show that PCD of neurons and glia occurs in most parts of the nervous system during development. It has been observed before and during synaptogenesis in the central nervous system as well as the peripheral nervous system.[24] However, there are a few differences between vertebrate species. For example, mammals exhibit extensive arborization followed by PCD in the retina while birds do not.[58] Although synaptic refinement in vertebrate systems is largely dependent on PCD, other evolutionary mechanisms also play a role.[24]

In plant tissue

Programmed cell death in plants has a number of molecular similarities to animal apoptosis, but it also has differences, the most obvious being the presence of a cell wall and the lack of an immune system that removes the pieces of the dead cell. Instead of an immune response, the dying cell synthesizes substances to break itself down and places them in a vacuole that ruptures as the cell dies.[59]

In "APL regulates vascular tissue identity in Arabidopsis",[60] Martin Bonke and his colleagues had stated that one of the two long-distance transport systems in vascular plants, xylem, consists of several cell-types "the differentiation of which involves deposition of elaborate cell-wall thickenings and programmed cell-death." The authors emphasize that the products of plant PCD play an important structural role.

Basic morphological and biochemical features of PCD have been conserved in both plant and animal kingdoms.[61] Specific types of plant cells carry out unique cell-death programs. These have common features with animal apoptosis—for instance, nuclear DNA degradation—but they also have their own peculiarities, such as nuclear degradation triggered by the collapse of the vacuole in tracheary elements of the xylem.[62]

Janneke Balk and Christopher J. Leaver, of the Department of Plant Sciences, University of Oxford, carried out research on mutations in the mitochondrial genome of sun-flower cells. Results of this research suggest that mitochondria play the same key role in vascular plant PCD as in other eukaryotic cells.[63]

PCD in pollen prevents inbreeding

During pollination, plants enforce self-incompatibility (SI) as an important means to prevent self-fertilization. Research on the corn poppy (Papaver rhoeas) has revealed that proteins in the pistil on which the pollen lands, interact with pollen and trigger PCD in incompatible (i.e., self) pollen. The researchers, Steven G. Thomas and Veronica E. Franklin-Tong, also found that the response involves rapid inhibition of pollen-tube growth, followed by PCD.[64]

In slime molds

The social slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum has the peculiarity of either adopting a predatory amoeba-like behavior in its unicellular form or coalescing into a mobile slug-like form when dispersing the spores that will give birth to the next generation.[65]

The stalk is composed of dead cells that have undergone a type of PCD that shares many features of an autophagic cell-death: massive vacuoles forming inside cells, a degree of chromatin condensation, but no DNA fragmentation.[66] The structural role of the residues left by the dead cells is reminiscent of the products of PCD in plant tissue.

D. discoideum is a slime mold, part of a branch that might have emerged from eukaryotic ancestors about a billion years before the present. It seems that they emerged after the ancestors of green plants and the ancestors of fungi and animals had differentiated. But, in addition to their place in the evolutionary tree, the fact that PCD has been observed in the humble, simple, six-chromosome D. discoideum has additional significance: It permits the study of a developmental PCD path that does not depend on caspases characteristic of apoptosis.[67]

Evolutionary origin of mitochondrial apoptosis

The occurrence of programmed cell death in protists is possible,[68][69] but it remains controversial. Some categorize death in those organisms as unregulated apoptosis-like cell death.[70][71]

Biologists had long suspected that mitochondria originated from bacteria that had been incorporated as endosymbionts ("living together inside") of larger eukaryotic cells. It was Lynn Margulis who from 1967 on championed this theory, which has since become widely accepted.[72] The most convincing evidence for this theory is the fact that mitochondria possess their own DNA and are equipped with genes and replication apparatus.

This evolutionary step would have been risky for the primitive eukaryotic cells, which began to engulf the energy-producing bacteria, as well as a perilous step for the ancestors of mitochondria, which began to invade their proto-eukaryotic hosts. This process is still evident today, between human white blood cells and bacteria. Most of the time, invading bacteria are destroyed by the white blood cells; however, it is not uncommon for the chemical warfare waged by prokaryotes to succeed, with the consequence known as infection by its resulting damage.

One of these rare evolutionary events, about two billion years before the present, made it possible for certain eukaryotes and energy-producing prokaryotes to coexist and mutually benefit from their symbiosis.[73]

Mitochondriate eukaryotic cells live poised between life and death, because mitochondria still retain their repertoire of molecules that can trigger cell suicide.[74] It is not clear why apoptotic machinery is maintained in the extant unicellular organisms. This process has now been evolved to happen only when programmed.[75] to cells (such as feedback from neighbors, stress or DNA damage), mitochondria release caspase activators that trigger the cell-death-inducing biochemical cascade. As such, the cell suicide mechanism is now crucial to all of our lives.

Programmed death of entire organisms

Clinical significance

c-Myc

c-Myc is involved in the regulation of apoptosis via its role in downregulating the Bcl-2 gene. Its role the disordered growth of tissue.[76]

Metastasis

A molecular characteristic of metastatic cells is their altered expression of several apoptotic genes.[76]

See also

- Anoikis

- Apoptosis-inducing factor

- Apoptosis versus Pseudoapoptosis

- Apoptosome

- Apoptotic DNA fragmentation

- Autolysis (biology)

- Autophagy

- Autoschizis

- Bcl-2

- BH3 interacting domain death agonist (BID)

- Calpains

- Caspases

- Cell damage

- Cornification

- Cytochrome c

- Cytotoxicity

- Diablo homolog

- Entosis

- Excitotoxicity

- Ferroptosis

- Inflammasome

- Mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- Mitotic catastrophe

- Necrobiology

- Necroptosis

- Necrosis

- p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA)

- Paraptosis

- Parthanatos

- Pyroptosis

- RIP kinases

- Wallerian degeneration

Notes and references

- Srivastava, R. E. in Molecular Mechanisms (Humana Press, 2007).

- Kierszenbaum, A. L. & Tres, L. L. (ed Madelene Hyde) (ELSEVIER SAUNDERS, Philadelphia, 2012).

- Raff, M (12 November 1998). "Cell suicide for beginners". Nature. 396 (6707): 119–22. doi:10.1038/24055. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 9823889.

- Engelberg-Kulka H, Amitai S, Kolodkin-Gal I, Hazan R (2006). "Bacterial Programmed Cell Death and Multicellular Behavior in Bacteria". PLOS Genetics. 2 (10): e135. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020135. PMC 1626106. PMID 17069462.

- Green, Douglas (2011). Means To An End. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-887-4.

- Kierszenbaum, Abraham (2012). Histology and Cell Biology - An Introduction to Pathology. Philadelphia: ELSEVIER SAUNDERS.

- Degterev, Alexei; Huang, Zhihong; Boyce, Michael; Li, Yaqiao; Jagtap, Prakash; Mizushima, Noboru; Cuny, Gregory D.; Mitchison, Timothy J.; Moskowitz, Michael A. (2005-07-01). "Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury". Nature Chemical Biology. 1 (2): 112–119. doi:10.1038/nchembio711. ISSN 1552-4450. PMID 16408008.

- Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P (2014). "Regulated necrosis: the expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways". Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 15 (2): 135–147. doi:10.1038/nrm3737. PMID 24452471.

- Lockshin RA, Williams CM (1964). "Programmed cell death—II. Endocrine potentiation of the breakdown of the intersegmental muscles of silkmoths". Journal of Insect Physiology. 10 (4): 643–649. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(64)90034-4.

- Vaux DL, Cory S, Adams JM (September 1988). "Bcl-2 gene promotes haemopoietic cell survival and cooperates with c-myc to immortalize pre-B cells". Nature. 335 (6189): 440–2. Bibcode:1988Natur.335..440V. doi:10.1038/335440a0. PMID 3262202.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2002". The Nobel Foundation. 2002. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- Schwartz LM, Smith SW, Jones ME, Osborne BA (1993). "Do all programmed cell deaths occur via apoptosis?". PNAS. 90 (3): 980–4. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90..980S. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.3.980. PMC 45794. PMID 8430112.;and, for a more recent view, see Bursch W, Ellinger A, Gerner C, Fröhwein U, Schulte-Hermann R (2000). "Programmed cell death (PCD). Apoptosis, autophagic PCD, or others?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 926 (1): 1–12. Bibcode:2000NYASA.926....1B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05594.x. PMID 11193023.

- Green, Douglas (2011). Means To An End. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-888-1.

- D. Bowen, Ivor (1993). "Cell Biology International 17". Cell Biology International. 17 (4): 365–380. doi:10.1006/cbir.1993.1075. PMID 8318948. Archived from the original on 2014-03-12. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- Kroemer G, Martin SJ (2005). "Caspase-independent cell death". Nature Medicine. 11 (7): 725–30. doi:10.1038/nm1263. PMID 16015365.

- Dixon Scott J.; Lemberg Kathryn M.; Lamprecht Michael R.; Skouta Rachid; Zaitsev Eleina M.; Gleason Caroline E.; Patel Darpan N.; Bauer Andras J.; Cantley Alexandra M.; et al. (2012). "Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death". Cell. 149 (5): 1060–1072. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. PMC 3367386. PMID 22632970.

- Jozef Bizik; Esko Kankuri; Ari Ristimäki; Alain Taieb; Heikki Vapaatalo; Werner Lubitz; Antti Vaheri (2004). "Cell-cell contacts trigger programmed necrosis and induce cyclooxygenase-2 expression". Cell Death and Differentiation. 11 (2): 183–195. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401317. PMID 14555963.

- Lang, F; Lang, KS; Lang, PA; Huber, SM; Wieder, T (2006). "Mechanisms and significance of eryptosis". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 8 (7–8): 1183–92. doi:10.1089/ars.2006.8.1183. PMID 16910766.

- Formigli, L; et al. (2000). "aponecrosis: morphological and biochemical exploration of a syncretic process of cell death sharing apoptosis and necrosis". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 182 (1): 41–49. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-4652(200001)182:1<41::aid-jcp5>3.0.co;2-7. PMID 10567915.

- Fadini, GP; Menegazzo, L; Scattolini, V; Gintoli, M; Albiero, M; Avogaro, A (25 November 2015). "A perspective on NETosis in diabetes and cardiometabolic disorders". Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases : NMCD. 26 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2015.11.008. PMID 26719220.

- Ross, Michael (2016). Histology: A Text and Atlas (7th ed.). p. 94. ISBN 978-1451187427.

- Chapter 10: All the Players on One Stage Archived 2013-05-28 at the Wayback Machine from PsychEducation.org

- Tau, GZ (2009). "Normal development of brain circuits". Neuropsychopharmacology. 35 (1): 147–168. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.115. PMC 3055433. PMID 19794405.

- Dekkers, MP (2013). "Death of developing neurons: new insights and implications for connectivity". Journal of Cell Biology. 203 (3): 385–393. doi:10.1083/jcb.201306136. PMC 3824005. PMID 24217616.

- Oppenheim, RW (1981). Neuronal cell death and some related regressive phenomena during neurogenesis: a selective historical review and progress report. In Studies in Developmental Neurobiology: Essays in Honor of Viktor Hamburger: Oxford University Press. pp. 74–133.

- Buss, RR (2006). "Adaptive roles of programmed cell death during nervous system development". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 29: 1–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112800. PMID 16776578.

- De la Rosa, EJ; De Pablo, F (October 23, 2000). "Cell death in early neural development: beyond the neurotrophic theory". Trends in Neurosciences. 23 (10): 454–458. doi:10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01628-3. PMID 11006461.

- Lossi, L; Merighi, A (April 2003). "In vivo cellular and molecular mechanisms of neuronal apoptosis in the mammalian CNS". Progress in Neurobiology. 69 (5): 287–312. doi:10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00051-0. PMID 12787572.

- Finlay, BL (1989). "Control of cell number in the developing mammalian visual system". Progress in Neurobiology. 32 (3): 207–234. doi:10.1016/0301-0082(89)90017-8. PMID 2652194.

- Yamaguchi, Yoshifumi; Miura, Masayuki (2015-02-23). "Programmed Cell Death in Neurodevelopment". Developmental Cell. 32 (4): 478–490. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2015.01.019. ISSN 1534-5807. PMID 25710534.

- Rubenstein, John; Pasko Rakic (2013). "Regulation of Neuronal Survival by Neurotrophins in the Developing Peripheral Nervous System". Patterning and Cell Type Specification in the Developing CNS and PNS: Comprehensive Developmental Neuroscience. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-397348-1.

- Constantino, Sotelo (2002). The chemotactic hypothesis of Cajal: a century behind. Progress in Brain Research. 136. pp. 11–20. doi:10.1016/s0079-6123(02)36004-7. ISBN 9780444508157. PMID 12143376.

- Oppenheim, Ronald (1989). "The neurotrophic theory and naturally occurring motorneuron death". Trends in Neurosciences. 12 (7): 252–255. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(89)90021-0. PMID 2475935.

- Dekkers, MP; Nikoletopoulou, V; Barde, YA (November 11, 2013). "Cell biology in neuroscience: Death of developing neurons: new insights and implications for connectivity". J Cell Biol. 203 (3): 385–393. doi:10.1083/jcb.201306136. PMC 3824005. PMID 24217616.

- Cowan, WN (2001). "Viktor Hamburger and Rita Levi-Montalcini: the path to the discovery of nerve growth factor". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 24: 551–600. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.551. PMID 11283321.

- Weltman, JK (February 8, 1987). "The 1986 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine awarded for discovery of growth factors: Rita Levi-Montalcini, M.D., and Stanley Cohen, Ph.D.". New England Regional Allergy Proceedings. 8 (1): 47–8. doi:10.2500/108854187779045385. PMID 3302667.

- Dekkers, M (April 5, 2013). "Programmed Cell Death in Neuronal Development". Science. 340 (6128): 39–41. Bibcode:2013Sci...340...39D. doi:10.1126/science.1236152. PMID 23559240.

- Southwell, D.G. (November 2012). "Intrinsically determined cell death of developing cortical interneurons". Nature. 491 (7422): 109–115. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..109S. doi:10.1038/nature11523. PMC 3726009. PMID 23041929.

- Kuida, K (1998). "Reduced apoptosis and cytochrome c-mediated caspase activation in mice lacking caspase 9". Cell. 94 (3): 325–337. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81476-2. PMID 9708735.

- Kuida, K (1996). "Decreased apoptosis in the brain and premature lethality in CPP32-deficient mice". Nature. 384 (6607): 368–372. Bibcode:1996Natur.384..368K. doi:10.1038/384368a0. PMID 8934524.

- Oppenheim, RW (2001). "Programmed cell death of developing mammalian neurons after genetic deletion of caspases". Journal of Neuroscience. 21 (13): 4752–4760. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04752.2001.

- Cecconi, F (1998). "Apaf1 (CED-4 homolog) regulates programmed cell death in mammalian development". Cell. 94 (6): 727–737. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81732-8. PMID 9753320.

- Hao, Z (2005). "Specific ablation of the apoptotic functions of cytochrome c reveals a differential requirement for cytochrome c and Apaf-1 in apoptosis". Cell. 121 (4): 579–591. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.016. PMID 15907471.

- Yoshida, H (1998). "Apaf1 is required for mitochondrial pathways of apoptosis and brain development". Cell. 94 (6): 739–750. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81733-x. PMID 9753321.

- Bonfanti, L (1996). "Protection of retinal ganglion cells from natural and axotomy-induced cell death in neonatal transgenic mice overexpressing bcl-2". Journal of Neuroscience. 16 (13): 4186–4194. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04186.1996.

- Martinou, JC (1994). "Overexpression of BCL-2 in transgenic mice protects neurons from naturally occurring cell death and experimental ischemia". Neuron. 13 (4): 1017–1030. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(94)90266-6. PMID 7946326.

- Zanjani, HS (1996). "Increased cerebellar Purkinje cell numbers in mice overexpressing a human bcl-2 transgene". Journal of Computational Neurology. 374 (3): 332–341. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19961021)374:3<332::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-2. PMID 8906502.

- Zup, SL (2003). "Overexpression of bcl-2 reduces sex differences in neuron number in the brain and spinal cord". Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (6): 2357–2362. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02357.2003.

- Fan, H (2001). "Elimination of Bax expression in mice increases cerebellar Purkinje cell numbers but not the number of granule cells". Journal of Computational Neurology. 436: 82–91. doi:10.1002/cne.1055.abs.

- Mosinger, Ogilvie (1998). "Suppression of developmental retinal cell death but not of photoreceptor degeneration in Bax-deficient mice". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 39: 1713–1720.

- White, FA (1998). "Widespread elimination of naturally occurring neuronal death in Bax-deficient mice". Journal of Neuroscience. 18 (4): 1428–1439. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01428.1998.

- Gianfranceschi, L (1999). "Behavioral visual acuity of wild type and bcl2 transgenic mouse". Vision Research. 39 (3): 569–574. doi:10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00169-2. PMID 10341985.

- Rondi-Reig, L (2002). "To die or not to die, does it change the function? Behavior of transgenic mice reveals a role for developmental cell death". Brain Research Bulletin. 57 (1): 85–91. doi:10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00639-6. PMID 11827740.

- Rondi-Reig, L (2001). "Transgenic mice with neuronal overexpression of bcl-2 gene present navigation disabilities in a water task". Neuroscience. 104 (1): 207–215. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00050-1. PMID 11311543.

- Buss, Robert R.; Sun, Woong; Oppenheim, Ronald W. (2006-07-21). "ADAPTIVE ROLES OF PROGRAMMED CELL DEATH DURING NERVOUS SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 29 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112800. ISSN 0147-006X.

- Sulston, JE (1980). "The Caenorhabditis elegans male: postembryonic development of nongonadal structures". Developmental Biology. 78 (2): 542–576. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(80)90352-8. PMID 7409314.

- Sulston2, JE (1983). "The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans". Developmental Biology. 100 (1): 64–119. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. PMID 6684600.

- Doe, Cq (1985). "Development and segmental differences in the pattern of neuronal precursor cells". Journal of Developmental Biology. 111 (1): 193–205. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(85)90445-2. PMID 4029506.

- Giebultowicz, JM (1984). "Sexual differentiation in the terminal ganglion of the moth Manduca sexta: role of sex-specific neuronal death". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 226 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1002/cne.902260107. PMID 6736297.

- Cook, B (1998). "Developmental neuronal death is not a universal phenomenon among cell types in the chick embryo retina". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 396 (1): 12–19. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980622)396:1<12::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-l. PMID 9623884.

- Collazo C, Chacón O, Borrás O (2006). "Programmed cell death in plants resembles apoptosis of animals" (PDF). Biotecnología Aplicada. 23: 1–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-14.

- Bonke M, Thitamadee S, Mähönen AP, Hauser MT, Helariutta Y (2003). "APL regulates vascular tissue identity in Arabidopsis". Nature. 426 (6963): 181–6. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..181B. doi:10.1038/nature02100. PMID 14614507.

- Solomon M, Belenghi B, Delledonne M, Menachem E, Levine A (1999). "The involvement of cysteine proteases and protease inhibitor genes in the regulation of programmed cell death in plants". The Plant Cell. 11 (3): 431–44. doi:10.2307/3870871. JSTOR 3870871. PMC 144188. PMID 10072402. See also related articles in The Plant Cell Online

- Ito J, Fukuda H (2002). "ZEN1 Is a Key Enzyme in the Degradation of Nuclear DNA during Programmed Cell Death of Tracheary Elements". The Plant Cell. 14 (12): 3201–11. doi:10.1105/tpc.006411. PMC 151212. PMID 12468737.

- Balk J, Leaver CJ (2001). "The PET1-CMS Mitochondrial Mutation in Sunflower Is Associated with Premature Programmed Cell Death and Cytochrome c Release". The Plant Cell. 13 (8): 1803–18. doi:10.1105/tpc.13.8.1803. PMC 139137. PMID 11487694.

- Thomas SG, Franklin-Tong VE (2004). "Self-incompatibility triggers programmed cell death in Papaver pollen". Nature. 429 (6989): 305–9. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..305T. doi:10.1038/nature02540. PMID 15152254.

- Crespi B, Springer S (2003). "Ecology. Social slime molds meet their match". Science. 299 (5603): 56–7. doi:10.1126/science.1080776. PMID 12511635.

- Levraud JP, Adam M, Luciani MF, de Chastellier C, Blanton RL, Golstein P (2003). "Dictyostelium cell death: early emergence and demise of highly polarized paddle cells". Journal of Cell Biology. 160 (7): 1105–14. doi:10.1083/jcb.200212104. PMC 2172757. PMID 12654899.

- Roisin-Bouffay C, Luciani MF, Klein G, Levraud JP, Adam M, Golstein P (2004). "Developmental cell death in dictyostelium does not require paracaspase". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (12): 11489–94. doi:10.1074/jbc.M312741200. PMID 14681218.

- Deponte, M (2008). "Programmed cell death in protists". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1783 (7): 1396–1405. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.018. PMID 18291111.

- Kaczanowski S, Sajid M and Reece S E 2011 Evolution of apoptosis-like programmed cell death in unicellular protozoan parasites Parasites Vectors 4 44

- Proto, W. R.; Coombs, G. H.; Mottram, J. C. (2012). "Cell death in parasitic protozoa: regulated or incidental?" (PDF). Nature Reviews Microbiology. 11 (1): 58–66. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2929. PMID 23202528. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2014-11-14.

- Szymon Kaczanowski; Mohammed Sajid; Sarah E Reece (2011). "Evolution of apoptosis-like programmed cell death in unicellular protozoan parasites". Parasites & Vectors. 4: 44. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-4-44. PMC 3077326. PMID 21439063.

- de Duve C (1996). "The birth of complex cells". Scientific American. 274 (4): 50–7. Bibcode:1996SciAm.274d..50D. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0496-50. PMID 8907651.

- Dyall SD, Brown MT, Johnson PJ (2004). "Ancient invasions: from endosymbionts to organelles". Science. 304 (5668): 253–7. Bibcode:2004Sci...304..253D. doi:10.1126/science.1094884. PMID 15073369.

- Chiarugi A, Moskowitz MA (2002). "Cell biology. PARP-1--a perpetrator of apoptotic cell death?". Science. 297 (5579): 200–1. doi:10.1126/science.1074592. PMID 12114611.

- Kaczanowski, S. Apoptosis: its origin, history, maintenance and the medical implications for cancer and aging. Phys Biol 13, http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1478-3975/13/3/031001

- Srivastava, Rakesh (2007). Apoptosis, Cell Signaling, and Human Diseases. Humana Press.