Capture of Le Sars

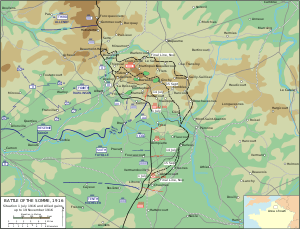

The Capture of Le Sars was a tactical incident during the Battle of the Somme. Le Sars is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France. The village lies along the Albert–Bapaume road. The village is situated 16 mi (26 km) south of Arras, at the junction of the D 11 and the D 929 roads. Courcelette lies to the south, Pys and Miraumont to the north-west, Eaucourt l'Abbaye to the south-east, the Butte de Warlencourt is to the north-east and Destremont Farm is south-west.

Military operations began in the area in September 1914 during the Race to the Sea, when the divisions of the II Bavarian Corps advanced westwards on the north bank of the Somme, passing through Le Sars towards Albert and Amiens. The village became a backwater until 1916, when the British and French began the Battle of the Somme (1 July – 13 November) and was the site of several air operations by the Royal Flying Corps, which attacked German supply dumps in the vicinity. During the Battle of Flers–Courcelette (15–22 September), the British Fourth Army advanced close to the village and operations to capture it began on 1 October. The village was overrun by the 23rd Division on 7 October, during the Battle of Le Transloy (1 October – 5 November), several hundred prisoners being taken from the 4th Ersatz Division.

After the village was captured, the crest of the rise to the east became the limit of the British advance. In the winter of 1916–1917, which was the worst for fifty years, the area was considered by the troops of the I Anzac Corps to be the foulest sector of the Somme front. The village was lost in March 1918 and recaptured for the last time in August by the 21st Division.

Background

1914

Troops of the 4th Bavarian Division reached Le Sars on 27 September, during the Battle of Albert (25–29 September 1914) and advanced on Bazentin le Petit and Longueval where the advance was stopped by French troops attacking eastwards from Albert. The 26th Württemburg Reserve Division advanced through Le Sars during the night of 27/28 September 28th Baden Reserve Division advanced on the south side of the Bapaume–Albert road, through the village towards Fricourt on 28 September.[1]

1916

On 9 July, 21 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps (RFC) bombed supply dumps at Le Sars. A flight of F.E.2b fighters of 22 Squadron escorting artillery observation and contact patrol aircraft on 15 July, attacked ground targets. One aircraft chased German soldiers down the Flers–Le Sars road and then attacked some cavalry hiding under trees and scattered them.[2] On 21 July, a 4 Squadron reconnaissance crew reported new entrenchments around the village.[3] Squadrons of the 15th Wing managed to attack Le Sars several times at the end of July and in August the III Brigade made several attacks on the village. On 27 August, air observers watched as infantry patrols probed towards Le Sars and made many low-flying attacks on German troops opposite the Fourth Army front.[4]

1–3 October

During an attack by III Corps in the Battle of Le Transloy, two battalions of the 7th Brigade of the 23rd Division attacked Destremont Farm and captured Flers Trench and part of Flers Support. Touch was gained with the 151st Brigade of the 50th Division on the right flank. On the north side of the Bapaume road, a long bombing fight eventually forced back the Germans in Flers Trench and touch was gained on the left flank with the 2nd Canadian Division. Patrols probed towards Le Sars, watched by the aviators of 34 Squadron and 3 Squadron but the parties were driven back by small-arms fire from the houses; the captured positions further back were consolidated. Rain began to fall around noon on 2 October and continued for two days, turning the ground to mud. The 50th Division was relieved by the 68th Brigade of the 23rd Division and opposite Le Sars, the 69th Brigade took over from the 70th Brigade. The 69th Brigade tried to bomb up Flers Support on the north side of the Bapaume road. The German 7th Division west of the Bapaume road and the right of the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division in Le Sars, were relieved by the 4th Ersatz Division on 3 October.[5]

Prelude

Preliminary operations

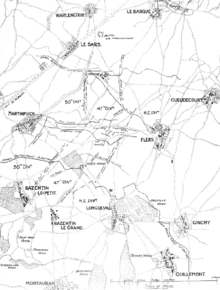

Two preliminary operations were conducted by the 69th Brigade, to capture the remaining length of Flers Support Trench and part of Flers Trench just south of the Bapaume road, which had been recaptured by a German counter-attack. Late on 3 October, two companies attacked Flers Support north of the main road and a party began a bombing attack on the recaptured part of Flers Trench at the same time. The attack on Flers Support had to over a distance of 100 yd (91 m) but the mud slowed progress and massed German machine-gun fire caused many casualties. The companies reached the German wire but could get no further. The bombing attack on Flers Trench succeeded but German artillery fire the next day, demolished the strong point and the party was withdrawn. Both attacks were costly failures, the attack on Flers Support leading to 139 casualties and the bombing attack another sixty losses.[6] On 6 October, the Tangle, a maze of trenches east of Le Sars, was attacked by the 11th Northumberland Fusiliers from the 68th Brigade but the troops were later withdrawn, due to the extent of German return fire. The weather began to improve on 4 October but high winds and low cloud made air observation difficult.[7] The rain stopped on 5 October and next day the ground rapidly dried. German artillery-fire on the area was continuous and the opposing lines were very close together, leading to six Germans being captured early on 6 October, who gave information which confirmed the results of gleanings from a German signal lamp, which were read by a German-speaker.[8]

British plan of attack

The 23rd Division had been ordered to attack Le Sars, in combination with an attack by the 47th Division on the Butte de Warlencourt but constant rain on the churned up ground, led postponements of the 23rd Division attack until 7 October.[9] The 23rd Division took over the front of the 50th Division front on 3 October, which gave the division a frontage of 1,000 yd (910 m) south of the Bapaume road and 400 yd (370 m) on the north side. Flers Support was held for 1,000 yd (910 m) on the right and in the centre to a point just south of the road. The division was to take the village and another 800 yd (730 m) of the Flers trenches on the left flank, the 2nd Canadian Division co-operating with the attacks on the trenches. (A postponement of the Canadian attack led to this part of the attack being put back to 8 October.) The village was built along the Albert–Bapaume road and most of the divisional front crossed the road at a right angle until 500 yd (460 m) from the right flank of the divisional front where the Flers trenches dog-legged to the east. An attack on the left would move parallel to the main road and an advance on the right would converge towards the north end of the village. In front of Le Sars on the right flank were two obstacles, a maze of trenches known as the Tangle and a sunken road leading from the west into the village. An advance from this flank would also be vulnerable to enfilade fire from the south end of the village.[10]

Battalions from the 68th and 69th brigades were to conduct the attack, in which the right-hand battalion of each brigade was to attack first. In the first phase, the 12th Durham Light Infantry (DLI) of the 68th Brigade was to capture the tangle and the sunken road. The 9th Green Howards of the 69th Brigade was to capture the village up to the central crossroads. In the second phase, the 13th DLI were to advance in the centre and take the north end of the village and the 11th West Yorkshire would advance twenty minutes after zero hour and take Flers Support on the north side of the road. Artillery support was to come from the 23rd, 50th and 47th divisional artilleries; after the preliminary bombardment a creeping barrage by 18-pounder field guns was to begin 400 yd (370 m) in front of the jumping off lines and move forward at 50 yd (46 m) per minute. A flanking barrage was arranged for the 11th West Yorkshire attack on Flers Support. A machine-gun barrage, Stokes mortar bombardment and tank support were also arranged.[11]

Battle

7 October

| Date | Rain (mm) |

Max–Min Temp (°F) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 63–41 | fine dull |

| 2 | 3 | 57–45 | wet mist |

| 3 | 0.1 | 70–50 | rain mist |

| 4 | 4 | 66–52 | dull wet |

| 5 | 6 | 66–54 | dull rain |

| 6 | 2 | 70–57 | sun rain |

| 7 | 0.1 | 66–52 | wind rain |

| 8 | 0.1 | 64–54 | rain |

On 7 October, German aircraft appeared over British artillery positions from Guedecourt to Flers and directed artillery fire onto the British batteries; the fighter pilots of IV Brigade found that the German aircraft had gone by the time that they arrived.[lower-alpha 1] Contact patrol pilots found that the westerly wind was so strong that they had to turn into the wind, for the observers to study the ground, which made them nearly stationary and easy targets for infantry ground fire. Two crew were wounded and many of the aircraft were damaged.[14] At 1:45 p.m., zero hour for the Fourth Army attack, the 12th DLI of the 68th Brigade attacked on the right flank, in four waves, behind a tank. The tank had arrived a minute after zero and cleared the Tangle of German defenders, before it was occupied by the infantry. When the tank turned left at the sunken Eaucourt l'Abbaye–Le Sars road, it was knocked out by a shell. The infantry came under machine-gun fire from the road and crossfire from machine-guns in Le Sars and from the right flank; the battalion formed a defensive flank from the tangle to the right of British front line. The 9th Green Howards of the 69th Brigade had advanced on the left flank at the same time and entered Le Sars close behind the barrage, heading for the first objective at the crossroads in the village.[15]

The German garrison was surprised and many soldiers were killed as they tried to man machine-guns but the Germans recovered quickly and managed to slow the British advance along the village. An unduly negative report of the progress of the battalion was given to a patrol of the 13th DLI, which had gone forward early to maintain liaison. The commander of the 13th DLI sent a company to attack the crossroads from the south, with a second company in support. The first company advanced in two waves that were stopped by German machine-gun fire; the second wave halted on the same line and engaged the Germans with rifle-fire and hand grenades. The supporting company came up and the attack restarted, meeting the 9th Green Howards at the crossroads, having killed or captured about 100 German troops. On the right the 12th DLI saw that the Germans in the sunken road had been outflanked, rushed the road and took possession. Twenty minutes after zero, the 11th West Yorkshire formed two companies in Flers Trench and two in Destremont Farm. The foremost and rearmost lines were struck by massed machine-gun fire from the front and the left flank and by artillery-fire. The two companies advancing from Destremont Farm lost all but 32 men and the attack failed.[16]

A bombing attack up Flers Trench which had begun at the same time, advanced for 50 yd (46 m) and captured the heads of two communication trenches to Flers Support. Bombing attacks up the communication trenches to Flers Support were met by determined German resistance and stopped. A company of the 10th Duke of Wellington's Regiment (10th Duke's) reinforced the 11th West Yorkshire. The 9th Green Howards in the village had consolidated and arranged a combined attack north of the village on Flers Support.[17] The German defence collapsed as soon as the third attack began and the German infantry hid or ran back from Flers Support. The Germans were engaged by artillery, machine-guns and rifle-fire and most were killed, a Lewis gunner in the village crossroads shooting down 70–80 men. A captured corporal was made to gain the surrender of survivors and more than 100 Germans gave up, as did another sixty stragglers. The 11th West Yorkshire were severely depleted and another two companies of the 10th Duke's were sent forward to help consolidate the 69th Brigade objectives.[18]

In the centre the 13th DLI was to advance through the Green Howards and capture the rest of the village. The companies of the 13th DLI and the Green Howards in the village left a platoon at the crossroads, to dig in and gain touch with the 12th DLI on the right and posted bombers at dug out entrances. Little resistance was met and the north end of the village was occupied. At 3:40 p.m. a third 13th DLI company advanced and joined the force in the village, to help dig strong points beyond the village to cover the avenues of attack from the east and north-east.[18] The 12th DLI had dug in along the sunken road beyond the Tangle and pushed out advanced posts on the right flank. The 13th DLI and the Green Howards consolidated the village and linked the new posts beyond the northern fringe, to the 12th DLI posts by 7:50 p.m.; a request was made for two tanks and two companies to attack the Butte de Warlencourt from the west, after patrols had found the area to be unoccupied but no troops were available.[15] Touch had not been gained with the 69th Brigade troops north-west of the village and a company of the 11th Northumberland Fusiliers with two machine-guns went forward after dark.[19]

8 October

The 23rd Division infantry and engineers spent the night consolidating the Le Sars defences and preparing for the attack with the Canadians, which had been postponed to 8 October. Two battalions formed carrying parties and two more cleared out 26th Avenue, the only communication trench in the area. The delayed 69th Brigade attack on Flers Trench and Flers Support to the north of the village was prepared overnight. To meet the attack of the 2nd Canadian Division and to capture a quarry behind the German trenches, two companies of the 8th York and Lancaster Regiment (8th York and Lancs), which had been attached to the 69th Brigade, took over on the divisional left flank during the night. Each company had a Stokes mortar and the Flers trenches were bombarded all night by the 23rd Division artillery. The Canadian attack on Regina trench began at 4:50 a.m. and the York and Lancs companies began to bomb along the trenches as soon as the barrage lifted. The attack succeeded swiftly and fifty prisoners and three machine-guns were captured, touch was gained with the Canadians and the quarry reconnoitred. It was found to be overlooked from German positions so a post was dug nearby in sheltered ground to overlook the area. A German counter-attack forced back the Canadians, leaving the 23rd Division flank open but no attack followed.[20]

Aftermath

Analysis

The high winds and the lack of observation in the preceding days due to rain, reduced the accuracy of the British artillery and the presence of German aircraft, which correspondingly increased the accuracy of German defensive barrages, contributed to the failure of the infantry to reach their objectives, except at Le Sars and beyond Gueudecourt.[14] The 47th Division attack on the Butte de Warlencourt succeeded on the right flank but failed to capture the butte, which was on the left flank. The 23rd Division had captured all its objectives and credited the artillery support for the success of the attacks, along with the efforts of the troops on the lines of communication, who from 2 to 8 October endured constant shelling. Telephone lines were frequently cut by the German artillery-fire but the brigade headquarters were rarely out of touch with the battalions for many minutes. Runners from battalion headquarters to the front, crossed ground under severe bombardment yet rarely delivered messages late. The initiative of the battalion commanders and the co-ordination of units, so that the 13th DLI immediately reinforced the Green Howards and the discretion of the 12th DLI in waiting at the tangle were commended.[21]

Casualties

The 23rd Division had 627 or 737 casualties according to either the divisional or the 68th Brigade records; the division took 528 prisoners.[22]

Subsequent operations

After the capture of Le Sars, the crest of the rise to the east, over which the spires of Bapaume could be glimpsed in clear weather, became the limit of the British advance.[23] During the winter of 1916–1917, which was the worst for fifty years, the area was considered by the troops of the I Anzac Corps to be the foulest sector of the Somme front. The village was lost on 25 March 1918 during Operation Michael.[24] Le Sars was recaptured for the last time on 25 August by the 21st Division, during the Second Battle of Bapaume (21 August – 1 September).[25]

Notes

- From 30 January 1916, each British army had a Royal Flying Corps brigade attached, which was divided into wings, the corps wing with squadrons responsible for close reconnaissance, photography and artillery observation on the front of each army corps and an army wing, which controlled the fighter squadrons and conducted long-range reconnaissance and bombing, using the aircraft types with the highest performance.[13]

Footnotes

- Whitehead 2010, pp. 30–33; Sheldon 2005, pp. 26, 28.

- Jones 2002, pp. 230–231.

- Gliddon 1987, p. 262.

- Jones 2002, pp. 252, 258, 295.

- Miles 1992, pp. 431–432.

- Sandilands 2003, pp. 109–110.

- Miles 1992, pp. 431–432, 434.

- Sandilands 2003, pp. 111–112.

- Sandilands 2003, p. 109.

- Sandilands 2003, pp. 110–111.

- Sandilands 2003, p. 111.

- Gliddon 1987, pp. 421–423.

- Jones 2002, pp. 147–148.

- Jones 2002, pp. 300–301.

- Miles 1992, p. 437.

- Sandilands 2003, pp. 112–113.

- Sandilands 2003, pp. 112–114.

- Sandilands 2003, p. 115.

- Sandilands 2003, pp. 115–116.

- Nicholson 1962, pp. 184–187; Sandilands 2003, pp. 116–117.

- Sandilands 2003, pp. 116–120.

- Sandilands 2003, p. 117.

- Stewart & Buchan 2003, p. 87.

- Edmonds, Davies & Maxwell-Hyslop 1995, p. 479.

- Edmonds 1993, p. 269.

References

- Edmonds, J. E.; Davies, H. R.; Maxwell-Hyslop, R. G. B. (1995) [1935]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-219-7.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1947]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: 8th August – 26th September The Franco-British Offensive. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. IV (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-191-6.

- Gliddon, G. (1987). When the Barrage Lifts: A Topographical History and Commentary on the Battle of the Somme 1916. Norwich: Gliddon Books. ISBN 978-0-947893-02-6.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. II (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-413-0. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Miles, W. (1992) [1938]. Military Operations in France and Belgium: 2 July to the End of the Battles of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press 1992 ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-169-5.

- Nicholson, G. W. L. (1962). Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationary. OCLC 557523890. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Sandilands, H. R. (2003) [1925]. The 23rd Division 1914–1919 (Naval & Military Press ed.). Edinburgh: Wm. Blackwood. ISBN 978-1-84342-641-7.

- Sheldon, J. (2005). The German Army on the Somme. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-269-8.

- Stewart, J.; Buchan, J. (2003) [1926]. The Fifteenth (Scottish) Division 1914–1919 (Naval & Military Press ed.). Edinburgh: Wm. Blackwood and Sons. ISBN 978-1-84342-639-4.

- Whitehead, R. J. (2013) [2010]. The Other Side of the Wire: With the German XIV Reserve Corps, September 1914 – June 1916. I (pbk. ed.). Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-908916-89-1.

Further reading

- Maude, A. H., ed. (1922). The History of the 47th (London) Division 1914–1919 (online ed.). London: Amalgamated Press. OCLC 6029656. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Snowden, K. L. (2001). British 21st Infantry Division on the Western Front 1914–1918: A Case Study in Tactical Evolution (PDF) (PhD). Department of Modern History School of Historical Studies: Birmingham University. OCLC 690664905. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Capture of Le Sars. |