Battle of Delville Wood

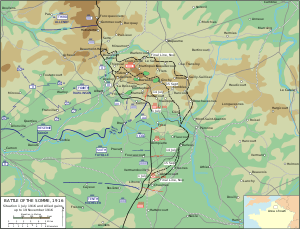

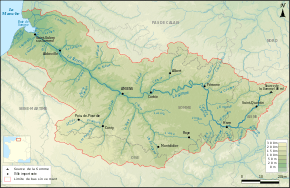

The Battle of Delville Wood (15 July – 3 September 1916) was a series of engagements in the 1916 Battle of the Somme in the First World War, between the armies of the German Empire and the British Empire. Delville Wood (Bois d'Elville), was a thick tangle of trees, chiefly beech and hornbeam (the wood has been replanted with oak and birch by the South African government), with dense hazel thickets, intersected by grassy rides, to the east of Longueval. As part of a general offensive starting on 14 July, which became known as the Battle of Bazentin Ridge (14–17 July), General Douglas Haig, Commander of the British Expeditionary Force, intended to capture the German second position between Delville Wood and Bazentin le Petit.

The attack achieved this objective and was a considerable though costly success. British attacks and German counter-attacks on the wood continued for the next seven weeks, until just before the Battle of Flers–Courcelette (15–17 September), the third British general attack in the Battle of the Somme. The 1st South African Infantry Brigade made its Western Front début as part of the 9th (Scottish) Division and captured Delville Wood on 15 July. The South Africans held the wood until 19 July, at a cost in casualties similar to those of many British brigades on 1 July. When captured, the village and wood formed a salient, which could be fired on by German artillery from three sides. The ground rose from Bernafay and Trônes woods, to the middle of the village and neither the village or the wood could be held without the other.

After the Battle of Bazentin Ridge, the British tried to advance on both flanks to straighten the salient at Delville Wood, to reach good jumping off positions for a general attack. The Germans tried to eliminate the salient and to retain the ground, which shielded German positions from view and overlooked British positions. For the rest of July and August, both sides fought for control of the wood and village but struggled to maintain the tempo of operations. Wet weather reduced visibility and made the movement of troops and supplies much more difficult; ammunition shortages and high casualties reduced both sides to piecemeal attacks and piecemeal defence on narrow fronts, except for a small number of bigger and wider-front attacks. Most attacks were defeated by defensive fire power and the effects of inclement weather, which frequently turned the battlefield into a slough of mud. Delville Wood is well preserved with the remains of trenches, a museum and a monument to the South African Brigade at the Delville Wood South African National Memorial.

Background

Strategic developments

In 1916, the Franco-British had absorbed the lessons of the failed breakthrough offensives of 1915 and abandoned attempts to break the German front in a sudden attack, as the increased depth of German defences had made this impossible. Attacks were to be limited, conducted over a wide front, preceded by artillery "preparation" and made by fresh troops.[1] Grignotage (nibbling) was expected to lead to the "crumbling" of German defences. The offensive was split between British and Dominion forces in the north (from Gommecourt to Maricourt) and the French in the south (from the River Somme to the village of Frey).[2] After two weeks of battle, the German defenders were holding firm in the north and centre of the British sector, where the advance had stopped except at Ovillers and Contalmaison. There had been substantial Entente gains from the Albert–Bapaume road southwards.[3]

The British attacks after 1 July and the rapid French advance on the south bank, led Falkenhayn on 2 July, to order that

... the first principle in position warfare must be to yield not one foot of ground and if it be lost to retake it by immediate counter-attack, even to the use of the last man.

— Falkenhayn[4]

and next day, General Fritz von Below issued an order of the day forbidding voluntary withdrawals,

The outcome of the war depends on the Second Army being victorious on the Somme.... The enemy must be made to pick his way forward over corpses.

— Below[5]

after his Chief of Staff, General Paul Grünert and the corps commander General Günther von Pannewitz, were sacked for ordering the XVII Corps to withdraw to the third position. Falkenhayn ordered a "strict defensive" at Verdun on 12 July and the transfer of more troops and artillery to the Somme front, which was the first strategic success of the Anglo-French offensive. By the end of July, finding reserves for the German defence of the Somme caused serious difficulties for Falkenhayn, who ordered an attack at Verdun intended to pin down French troops. The Brusilov Offensive continued and the German eastern armies had to take over more of the front from the Austro-Hungarians when Brody fell on 28 July, to cover Lemberg. Russian attacks were imminent along the Stochod river and the Austro-Hungarian armies were in a state of disarray. Conrad von Hötzendorf, the Austro-Hungarian Chief of the General Staff, was reluctant to take troops from the Italian front, when the Italian army was preparing the Sixth Battle of the Isonzo, which began on 6 August.[6]

Tactical developments

(top left, clockwise) General Douglas Haig, commander of the BEF, General Rawlinson, commander of the Fourth Army

General von Below, commander of the German 2nd Army, General von Falkenhayn, Chief of the General Staff of the German army.

On 19 July, the German 2nd Army was split and a new 1st Army was established, to command the German divisions north of the Somme. The 2nd Army kept the south bank, under General Max von Gallwitz, transferred from Verdun, who was also made commander of Armeegruppe Gallwitz-Somme with authority over Below and the 1st Army. Lossberg remained as the 1st Army Chief of Staff and Bronsart von Schellendorff took over for the 2nd Army. Schellendorff advocated a counter-offensive on the south bank, which was rejected by Falkenhayn, because forces released from the Verdun front were insufficient, five divisions having been sent to the Russian Front in July. On 21 July, Falkenhayn ruled that no more divisions could be removed from quiet fronts for the Somme until exhausted divisions relieved them and that he needed seven "fought out" divisions to replace those already sent to the Somme. Gallwitz began to reorganise the artillery and curtailed harassing and retaliatory fire to conserve ammunition for defensive fire during Anglo-French attacks. From 16–22 July, 32 heavy gun and howitzer batteries arrived on the Somme and five reconnaissance flights, three artillery flights, three bombing flights and two fighter squadrons reached the area. Since 1 July, thirteen fresh divisions had arrived on the north bank of the Somme and three more were ready to join the defence.[7]

The strain on the German defenders on the Somme grew worse in August and unit histories made frequent reference to high losses and companies being reduced to eighty men before relief. Many German divisions came out of a period on the Somme front with at least 4,500 casualties and some German commanders suggested a change to the policy of unyielding defence. The front line was lightly held, with reserves further back in a defensive zone but this had little effect on the losses caused by the Anglo-French artillery. Movement behind the German front was so dangerous that regiments carried rations and water for a four- to five-day tour with them. Behind the line, construction work on new rear lines was constant despite shortages of materials and rail lines becoming overloaded with troop trains. Supply trains were delayed and stations near the front were bombarded by artillery and by aircraft. The local light railways were insufficient and lorries and carts were pressed into use, using roads which while paved, needed constant maintenance, which was difficult to ensure with the troops available.[8]

The German artillery suffered many losses and the number of damaged guns exceeded the repair capacity of workshops behind the front. Inferior ammunition exploded prematurely, bursting gun barrels. Destruction, wear and tear from 26 June to 28 August, led to 1,068 of the 1,208 field guns and 371 of the 820 heavy guns in the Armeegruppe being lost. The Anglo-French maintained air superiority but German air reinforcements began to arrive by mid-July. More artillery was sent to the Somme but until the reorganisation and centralisation of artillery control had been completed, counter-battery fire, barrage-fire and co-operation with aircraft remained inadequate. Gallwitz considered plans for the relief attack but lack of troops and ammunition made it impractical, particularly after 15 July, when Falkenhayn withheld more fresh divisions and the 1st Army had to rely on the 2nd Army for reinforcements. In early August, an attempt was made to use Landsturm men over 38 years old, who proved a danger to themselves and were withdrawn.[9]

Prelude

British offensive preparations

British attacks south of the road between Albert and Bapaume began on 2 July, despite congested supply routes to the French XX Corps and the British XIII, XV and III Corps. La Boisselle near the road was captured on 4 July, Bernafay and Caterpillar woods were occupied from 3–4 July and then fighting to capture Trônes Wood, Mametz Wood and Contalmaison took place until early on 14 July. As German reinforcements reached the Somme front, they were thrown into battle piecemeal and had many casualties. Both sides were reduced to improvised operations, which were hurried and poorly organised. Troops who were unfamiliar with the ground had little time for reconnaissance and were supported by artillery which was poorly co-ordinated with the infantry and sometimes fired on ground occupied by friendly troops. British attacks in this period have been criticised as uncoordinated, tactically crude and wasteful of manpower, which gave the Germans an opportunity to concentrate their inferior resources on narrow fronts.[10]

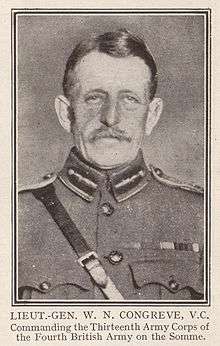

The Battle of Bazentin Ridge (14–17 July) was planned as a joint attack by XV and XIII Corps, whose troops would assemble in no man's land in darkness and attack at dawn after a five-minute hurricane bombardment. Haig was sceptical of the plan but eventually accepted the views of Rawlinson and the corps commanders, Lieutenant-General Henry Horne and Lieutenant-General Walter Congreve. Preparatory artillery bombardments began on 11 July and on the night of 13/14 July, British troops advanced stealthily across no man's land, which in parts was 1,200 yd (1,100 m) wide, to within 300–500 yd (270–460 m) of the German front line and then crept forward. At 3:20 a.m., the hurricane bombardment began and the British began to run forward. On the right flank, the 18th (Eastern) Division (Major-General Ivor Maxse), captured Trônes Wood in a subsidiary operation and the 9th (Scottish) Division (Major-General William Furse) was repulsed from Waterlot Farm but on the left got into Delville Wood. The 21st, 7th and 3rd Division on the left (northern) flank, took most of their objectives. By mid-morning 6,000 yd (5,500 m) of the German second position had been captured, cavalry had been sent forward and the German defenders thrown into chaos.[11]

Longueval and Delville Wood

The village of Longueval enclosed a cross-roads which ran south-west to Montauban, west to the two Bazentins, north to Flers and east to Ginchy.[12] South African forces used the English place names in Longueval and Delville Wood, as they were more meaningful than French terms.[13] Pall Mall led north from Montauban and Bernafay Wood, to the cross-roads on the southern fringe of the village, where Sloan Street branched to the west, to a junction with Clarges Street and Pont Street. Dover Street led to the south-east and met a track running north from Trônes Wood. Two roads converged on Pall Mall at the main square; North Road ran between Flers and High Wood, with a path to the west meeting Pont Street, which ran into High Wood and the second road ran south-east to Guillemont. Clarges Street ran west from the village square to Bazentin le Grand and Prince's Street ran east through the middle of Delville Wood.[14]

Parallel to Clarges Street, about 300 yd (270 m) further north, ran Duke Street, both bounded on the west by Pont Street and by Piccadilly on the east side. Orchards lay between Piccadilly and North Street, beyond which Flers Road forked to the right, skirting the north-west edge of Delville Wood.[15] The wood lay north of the D20 road, west of Ginchy and the north-west edge was adjacent to the D 197 Flers road.[14] Delville Wood was bounded on the southern edge by South Street, which was linked to Prince's Street by Buchanan Street to the west, Campbell Street in the centre and King Street to the east, three parallel rides which faced north. Running east from Buchanan Street and parallel to Prince's Street was Rotten Row. On the north side of Prince's Street ran Strand, Regent Street and Bond Street, three rides to the northern fringe of the wood.[16]

British plans of attack

General Sir Henry Rawlinson, commander of the Fourth Army ordered Congreve to use XIII Corps to capture Longueval, while the XV Corps (Lieutenant-General Horne) was to cover the left flank.[17] Rawlinson wanted to advance across no man's land at night for a dawn attack after a hurricane bombardment to gain surprise. Haig opposed the plan because of doubts about inexperienced New Army divisions assembling on the battlefield at night but eventually deferred to Rawlinson and the corps commanders, after modifications to their plan. An advance to Longueval could not begin until Trônes Wood was in British possession as it dominated the approach from the south. The capture of Longueval would then require the occupation of Delville Wood on the north-eastern edge of the town. If Delville Wood was not captured German artillery observers could overlook the village and German infantry would have an ideal jumping-off point for attacks on Longueval.[17]

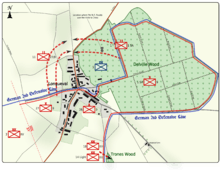

A British advance would deepen the salient already formed to the north-east of Montauban but also assist British attacks to the south on Ginchy and Guillemont and on High Wood to the north-west. The 9th (Scottish) Division was to attack Longueval and the 18th (Eastern) Division on the right was to occupy Trônes Wood. Furse, ordered that the Longueval attack be led by the 26th Brigade. The 8th (Service) Battalion, Black Watch and the 10th (Service) Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders would lead, with the 9th (Service) Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders in support and the 5th (Service) Battalion, Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders in reserve. The 27th Brigade would follow on, to mop up any bypassed German troops and reinforce the leading battalions, once they had entered the village. When Longueval had been secured, the 27th Brigade was to pass through the 26th Brigade to take Delville Wood. The 1st South African Brigade was to be kept in reserve.[17]

German defensive preparations

Despite considerable debate among German staff officers, Falkenhayn based defensive tactics in 1916 on unyielding defence and prompt counter-attacks, when ground had been lost.[lower-alpha 1] On the Somme front Falkenhayn's construction plan of January 1915 had been completed by early 1916. Barbed wire obstacles had been enlarged from one belt 5–10 yd (4.6–9.1 m) wide to two, 30 yd (27 m) wide and about 15 yd (14 m) apart. Double and triple thickness wire was used and laid 3–5 ft (0.91–1.52 m) high. The front line had been increased from one line to three, 150–200 yd (140–180 m) apart, the first trench occupied by sentry groups, the second (Wohngraben) for the front-trench garrison and the third trench for local reserves. The trenches were traversed and had sentry-posts in concrete recesses built into the parapet. Dugouts had been deepened from 6–9 ft (1.8–2.7 m) to 20–30 ft (6.1–9.1 m), 50 yd (46 m) apart and large enough for 25 men. An intermediate line of strongpoints (Stutzpunktlinie) about 1,000 yd (910 m) behind the front line was also built. Communication trenches ran back to the reserve line, renamed the second line, which was as well-built and wired as the first line. The second line was beyond the range of Allied field artillery, to force an attacker to stop and move field artillery forward before assaulting the line.[19]

The German front line lay along the old third position, which in this area ran from the southern edge of Bazentin le Grand to the south fringe of Longueval and then curved south-east past Waterlot Farm and Guillemont. An Intermediate Line ran roughly parallel behind Delville Wood on a reverse slope, the wood being on a slight ridge which extended east from the village.[14] Longueval had been fortified with trenches, tunnels, concrete bunkers and had two field guns. The village was garrisoned by the divisions of IV Corps (General Sixt von Armin) and the 3rd Guard Division.[20] The north and north-west was held by Thuringian Infantry Regiment 72 of the 8th Division. In and around Delville Wood, an area of about 0.5-square-mile (1.3 km2), which abutted the east side of Longueval and extended to within 0.5-mile (0.80 km) of Ginchy, were Infantry Regiment 26 of the 7th Division, Thuringian Infantry Regiment 153 and Infantry Regiment 107.[14][21] A British attack would have to advance uphill from Bernafay and Trônes woods, across terrain with a similar shape to a funnel, broad in the south and narrowing towards Longueval in the north.[17] Armin suspected that an attack would begin on 13 or 14 July.[22]

Battle

French Tenth and Sixth armies

The French Sixth Army was pushed back from Biaches south of the Somme by a German counter-attack on 14 July, which was retaken along with Bois Blaise and La Maisonette. (Military units after the first mentioned are French unless specified.) On 20 July, I Corps attacked at Barleux, where the 16th Division took the German front trench and was then stopped short of the second objective by massed German machine-gun fire, before being counter-attacked and pushed back to the start line with 2,000 casualties. Refusals of orders occurred in the 2nd Colonial Division, which led to two soldiers being court-martialled and shot. Joffre issued orders that the possibility of a rapid end to the war was to be played down.[23] XXXV Corps had been moved from the north bank and reinforced by two divisions and attacked Soyécourt, Vermandovillers and high ground beyond, as a prelude to attacks by the Tenth Army from Chilly, northwards to the Sixth Army boundary.[24]

XXXV Corps captured the north end of Soyécourt and Bois Étoile but then bogged down against flanking machine-gun fire and counter-attacks. For the remainder of July and August, the German defence on the south bank contained the French advance. On the north side of the Somme, the Sixth Army advanced by methodical attacks against points of tactical value, to capture the German second position from Cléry to Maurepas. VII Corps was brought in on the right of XX Corps, for the attack on the German second position, which was on the opposite side of a steep ravine, behind an intermediate line and strong points in the valley. On 20 July, XX Corps attacked with the 47th and 153rd divisions; the 47th Division attack on the right was stopped by machine-gun fire in front of Monacu Farm, as the left flank advanced 800–1,200 m (870–1,310 yd) and took Bois Sommet, Bois de l'Observatoire and the west end of Bois de la Pépinière. The 153rd Division captured its objectives, despite the British 35th Division further north being driven back from Maltz Horn Farm.[25]

1st South African Brigade

14–16 July

The divisions of XIII Corps and XV Corps attacked on 14 July, just before dawn at 3:25 a.m., on a 4 mi (6.4 km) front. The infantry moved forward over no man's land to within 500 yd (460 m) of the German front line and attacked after a five-minute hurricane bombardment, which gained a measure of tactical surprise. Penetrating the German second line by a sudden blow on a limited front was relatively easy but consolidating and extending the breach against alerted defenders was far more difficult. The attack on Longueval met with initial success, the thin German outpost line being rapidly overwhelmed. By mid-morning, the British troops had reached the village square, by fighting house-to-house.[26] The effect of British artillery-fire diminished because the north end of the village was out of view on a slight north-facing slope; German reinforcements reached the village; artillery and machine–gun fire from Delville Wood and Longueval, raked the 26th Brigade.[12] By the afternoon, the western and south-western parts of the village had been occupied. The 27th Brigade, intended for the attack on Delville Wood, had been used to reinforce the attack. At 1:00 p.m. Furse ordered the 1st South African Brigade to take over the attack on the wood.[26]

Three battalions of the 1st South African Brigade were to attack Delville Wood, while the 1st Battalion continued as a reinforcement of the 26th and 27th brigades in Longueval.[27] The attack at 5:00 p.m. was postponed to 7:00 p.m. and then to 5:00 a.m. on 15 July, due to the slow progress in the village. Brigadier-General Henry Lukin was ordered to take the wood at all costs and that his advance was to proceed, even if the 26th and 27th Brigades had not captured the north end of the village.[28] Lukin ordered an attack from the south-west corner of the wood on a battalion front, with the 2nd Battalion forward, the 3rd Battalion in support and the 4th Battalion in reserve. The three battalions moved forward from Montauban before first light, under command of Lieutenant–Colonel W. E. C. Tanner of the 2nd Battalion. On the approach, Tanner received instructions to detach two companies to the 26th Brigade in Longueval and sent B and C companies of the 4th Battalion.[29] The 2nd Battalion reached a trench occupied by the 5th Camerons, which ran parallel to the wood and used this as a jumping-off line for the attack at 6:00 a.m.[28]

The attack met little resistance and by 7:00 a.m. the South Africans had captured the wood south of Prince's Street. Tanner sent two companies to secure the northern perimeter of the wood. Later during the morning, the 3rd Battalion advanced towards the east and north-east of the wood and by 2:40 a.m. Tanner reported to Lukin that he had secured the wood except for a strong German position in the north-western corner adjoining Longueval.[30] The South African Brigade began to dig in around the fringe of the wood, in groups forming strong–points supported by machine–guns.[28] The brigade occupied a salient, in contact with the 26th Brigade only along the south-western edge of the wood adjoining Longueval.[31] The troops carried spades but digging through roots and remnants of tree trunks, made it impossible to dig proper trenches and only shallow shell scrapes could be prepared before German troops began to counter-attack the wood.[32]

A battalion of the 24th Reserve Division counter-attacked from the south-east at 11:30 a.m., having been given five minutes' notice but only managed to advance to within 80 yd (73 m) of the wood before being forced to dig in. An attack by a second battalion from the Ginchy–Flers road was also repulsed, the battalions losing 528 men. In the early afternoon a battalion of the 8th Division attacked the north-eastern face of the wood and was also repulsed, after losing all its officers.[27] At 3:00 p.m. on 15 July Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 6 of the 10th Bavarian Division attacked in force from the east but was partially driven back by rifle and machine-gun fire. At 4:40 p.m. Tanner reported to Lukin that German forces were massing to the north of the wood and he called for reinforcements, as the South Africans had already lost a company from the 2nd (Natal and Free State) Battalion.[28]

Tanner had received one company from the 4th (Scottish) Battalion from Longueval and Lukin sent a second company forward to reinforce the 3rd (Transvaal & Rhodesia) Battalion. Lukin sent messages urging Tanner and the battalion commanders to dig in regardless of fatigue, as heavy artillery fire was expected during the night or early the next morning.[28] As night fell German high explosive and gas shelling increased in intensity and a German counter-attack began at midnight with orders to recapture the wood at all costs. The attack was made by three battalions from the 8th and 12th Reserve divisions and managed to reach within 50 yd (46 m), before being driven under cover by artillery and machine-gun fire. Later that night, fire into Delville Wood, from four German Feldartillerie brigades, reached a rate of 400 shells per minute.[28]

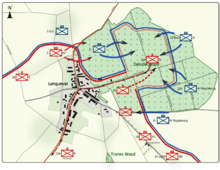

On 14–15 July the 18th Division had cleared Trônes Wood to the south and had established a line up to Maltz Horn Farm, adjacent to the French 153rd Division.[lower-alpha 2] At 12:35 a.m. Lukin was ordered to capture the north-west part of Delville Wood at all costs and then to advance westwards to meet the 27th Brigade, as it attacked north and north–eastwards through Longueval. The advance began on 16 July at 10:00 a.m. but the casualties of the South Africans had reduced the weight of the attack, which was repulsed by the German defenders. The 27th Brigade advance were pinned down in the village by machine-gun fire from an orchard in the north end of Longueval. The survivors fell back to their trenches midway in the wood and were bombarded for the rest of the day. The situation became desperate and was made worse by an attack by Thuringian Infantry Regiment 153.[34]

17–19 July

In the evening of 16 July, the South Africans withdrew south of Prince's Street and east of Strand Street, for a bombardment on the north-west corner of the wood and the north end of Longueval. On 17 July, the 27th Brigade attacked northwards in Longueval and the 2nd South African Battalion plus two companies of the 1st Battalion, attacked westwards in the wood. The South African attack was a costly failure and the survivors were driven back to their original positions, which came under increased German artillery-fire in the afternoon.[35] In the evening Tanner was wounded and replaced by Lieutenant-Colonel E. F. Thackeray, of the 3rd Battalion, as commander in Delville Wood. The 9th Division drew in its left flank and the 3rd Division (Major-General J. A. L. Haldane), was ordered to attack Longueval from the west during the night. Huge numbers of shells were fired into the wood and Lukin ordered the men into the north-western sector, to support the attack on Longueval due at 3:45 a.m. During the night, the German 3rd Guards Division advanced behind a creeping barrage of 116 field guns and over 70 medium guns. The Germans reached Buchanan and Princes streets, driving the South Africans back from their forward trenches, with many casualties.[36]

The Germans spotted the forming up of the troops in the wood and fired an unprecedented bombardment; every part of the area was searched and smothered by shells.[37] During the barrage, German troops attacked and infiltrated the South African left flank, from the north-west corner of the wood. By 2:00 p.m., the South African position had become desperate as German attacks were received from the north, north-west and east, after the failure of a second attempt to clear the north-western corner. At 6:15 p.m., news was received that the South Africans were to be relieved by the 26th Brigade. The 3rd Division attack on Longueval had taken part of the north end of the village and Armin ordered an attack by the fresh 8th Division, against the Buchanan Street line from the south east, forcing Thackeray to cling to the south western corner of the wood for two days and nights, the last link to the remainder of the 9th Division (Map 4).[37]

On the morning of 18 July, the South Africans received support from the relatively fresh 76th Brigade of the 3rd Division, which attacked through Longueval into the south-western part of the wood, to join up with A Company of the 2nd South African Battalion, until the 76th Brigade was forced back by German artillery-fire. In the south, the South Africans recovered some ground because the Germans had made limited withdrawals ready for counter-attacks in other areas.[38] A German bombardment during the night became intense at sunrise and c. 400 shells per minute fell into Longueval and the wood, along with heavy rain, which filled shell-craters. At 3:15 p.m., German infantry attacked Longueval and the wood from the east, north and north-east. Reserve Infantry Regiment 107 attacked westwards along the Ginchy–Longueval road, towards the 3rd South African Regiment, which was dug in along the eastern fringe of the wood, which commanded Ginchy. The German infantry were cut down by small-arms fire as soon as they advanced and no more attempts were made to advance beyond the intermediate line.[39]

The main German attack was made by the 8th Division and part of the 5th Division from the north and north-east. Elements of nine battalions attacked with 6,000 men. Infantry Regiment 153 was to advance from south of Flers, to recapture Delville Wood and reach the second position along the southern edge of the wood, the leading battalion to occupy the original second line from the Longueval–Guillemont road to Waterlot Farm, the second battalion to dig in along the southern edge of the wood and the third battalion to occupy Prince's Street along the centre of the wood. At first the advance moved along the sunken Flers road, 150 yd (140 m) north of the wood, which was confronted by the 2nd South African Regiment along the north edge of the wood.[39] By afternoon, the north perimeter had been pushed further south by German attacks. Hand-to-hand fighting occurred all over the wood, as the South Africans could no longer hold a consolidated and continuous line, many of them being split into small groups without mutual support.[20] By the afternoon of 18 July, the fresh Branderberger Regiment had also engaged. A German officer wrote

... Delville Wood had disintegrated into a shattered wasteland of shattered trees, charred and burning stumps, craters thick with mud and blood, and corpses, corpses everywhere. In places they were piled four deep. Worst of all was the lowing of the wounded. It sounded like a cattle ring at the spring fair....

— German officer[40]

and by 19 July, the South African survivors were being shelled and sniped from extremely close range.[37]

In the early morning, Reserve Infantry Regiment 153 and two companies of Infantry Regiment 52, entered the wood from the north and wheeled to attack the 3rd South African Battalion from behind, capturing six officers and 185 men from the Transvaal Battalion; the rest were killed.[41] By mid morning, Black Watch, Seaforth and Cameron Highlanders in Longueval tried to charge into the wood but were repulsed by German small-arms fire from the north-west corner of the wood. The brigade was short of water, without food and unable to evacuate wounded; many isolated groups surrendered, after they ran out of ammunition. In the afternoon, the 53rd Brigade advanced from the base of the salient to reach Thackeray at the South African headquarters but was unable to reach the forward elements of the South African brigade. This situation prevailed through the night of 19–20 July.[42]

20 July

On 20 July, the 76th Brigade of the 3rd Division was again pushed forward to attempt to relieve the 1st South African Brigade. The Royal Welsh Fusiliers attacked towards the South Africans but by 1:00 p.m., Thackeray had informed Lukin that his men were exhausted, desperate for water and could not repel a further attack.[43] Troops of the Suffolk Regiment and the 6th Royal Berkshires broke through and joined with the last remaining South African troops, in the segment of the wood still under South African control.[37] Thackeray marched out of the wood, leading two wounded officers and 140 other ranks, the last remnant of the South African Brigade. Piper Sandy Grieve of the Black Watch, who had fought against the South African Boers as part of the Highland Brigade, in the Battle of Magersfontein in 1899 and been wounded through the cheeks, played the South Africans out.[44] The survivors spent the night at Talus Boise and next day withdrew to Happy Valley south of Longueval.[45]

21 July – 20 August

| Date | Rain mm |

°F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 July | 0.0 | 75°–54° | haze |

| 2 July | 0.0 | 75°–54° | fine |

| 3 July | 2.0 | 68°–55° | fine |

| 4 July | 17.0 | 70°–55° | rain |

| 5 July | 0.0 | 72–52° | dull |

| 6 July | 2.0 | 70°–54° | rain |

| 7 July | 13.0 | 70°–59° | rain |

| 8 July | 8.0 | 73°–52° | rain |

| 9 July | 0.0 | 70°–53° | dull |

| 10 July | 0.0 | 82°–48° | dull |

| 11 July | 0.0 | 68°–52° | dull |

| 12 July | 0.1 | 68°–? | dull |

| 13 July | 0.1 | 70°–54° | dull |

| 14 July | 0.0 | 70°–? | dull |

| 15 July | 0.0 | 72°–47° | fine |

| 16 July | 4.0 | 73°–55° | dull |

| 17 July | 0.0 | 70°–59° | mist |

| 18 July | 0.0 | 72°–52° | dull |

| 19 July | 0.0 | 70°–50° | dull |

| 20 July | 0.0 | 75°–52° | fine |

| 21 July | 0.0 | 72°–52° | fine |

| 22 July | 0.1 | 77°–55° | dull |

| 23 July | 0.0 | 68°–54° | dull |

| 24 July | 0.0 | 70°–55° | dull hot |

| 25 July | 0.0 | 66°–50° | dull |

| 26 July | 0.0 | 66°–50° | dull |

| 27 July | 8.0 | 81°–61° | haze |

| 28 July | 0.0 | 77°–59° | dull hot |

| 29 July | 0.0 | 81°–57° | dull |

| 30 July | 0.0 | 82°–57° | fine |

| 31 July | 0.0 | 82°–59° | hot |

A British bombardment preparatory to the offensive planned for the night of 22/23 July, began at 7:00 p.m. on 22 July. The 3rd Division attacked Delville Wood and the north end of Longueval, from the west with the 9th Brigade from Pont Street, as the 95th Brigade of the 5th Division attacked German strong-points in the orchards to the north. The two battalions of the 3rd Division had only recently arrived and had received their orders at the last minute. The bombardment was considered poor but the attack began at 3:40 a.m. and the troops were quickly engaged by German machine-guns from the front and left flank. The advance covered a considerable distance but was forced back to Piccadilly and then Pont Street, where the survivors were bombarded by German artillery. The two 95th Brigade battalions also had early success and threatened the German right flank. The Flers road was crossed and a strong point captured and consolidated but then a German counter-attack pushed both battalions back to Pont Street; a second attack was planned and then cancelled.[47] Relief of the 3rd Division began on the night of 25 July by the 2nd Division, ready for another attack on most of Delville Wood, when the west end of Longueval and the rest of the wood were attacked by the 5th Division, in a larger operation by XIII Corps and XV Corps due on 27 July.[48]

German artillery fired on the routes into Longueval and sent alarm signals aloft from the front line several times each day. On 27 July, every British gun in range, fired on the wood and village from 6:10 –7:10 a.m., as infantry patrols went forward through a German counter-bombardment, to study the effect of the British fire. The patrols found "a horrible scene of chaos and destruction".[49][lower-alpha 3] When the bombardment began, about sixty German soldiers surrendered to the 2nd Division and at zero hour, two battalions of the 99th Brigade advanced, with trench-mortar and machine-gun sections in support. The infantry found a shambles of shell-craters, shattered trees and débris. After a ten-minute advance, the troops reached a trench along Prince's Street, full of dead and wounded German infantry and took several prisoners. The advance was continued when the barrage lifted by the supporting companies, which moved to the final objective about 50 yd (46 m) inside the northern fringe of the wood around 9:00 a.m. A third battalion moved forward to mop up and guard the flanks but avoided the east end of the wood. As consolidation began, German artillery fired along Prince's Street and caused far more casualties than those suffered during the attack.[49]

On the left flank, the 15th Brigade of the 5th Division, attacked with one battalion forward and one in support. German artillery-fire before zero hour was so extensive, that most of a company of the forward battalion was buried and the Stokes mortars knocked out. The support battalion was pushed forward and both advanced on time into the west end of the wood, where they linked with the 99th Brigade. The attack on Longueval was hampered by the German barrage to the south, which cut communications and by several machine-guns firing from the village. An attempt by the Germans to reinforce the garrison from Flers failed, when British artillery-fire fell between the villages but the German infantry held out at the north end of Longueval. A British line was eventually established from the north-west of Delville Wood, south-west into the village, below the orchards at Duke Street and Piccadilly. A German counter-attack began at 9:30 a.m., from the east end of Delville Wood against the 99th Brigade.[51]

The German attack eventually penetrated behind Prince's Street and pushed the British line back to face north-east. Communications with the rear were cut several times and when the Brigade commander contradicted a rumour that the wood had been lost, the 2nd Division headquarters assumed that the wood was empty of Germans. Skirmishing continued and during the night, two battalions of the 6th Brigade took over from the 99th Brigade.[52] The 15th Brigade was relieved by the 95th Brigade that night and next morning Duke Street was occupied unopposed. On 29 July, the XV Corps artillery fired a bombardment for thirty minutes and at 3:30 p.m., a battalion advanced on the left flank, to a line 500 yd (460 m) north of Duke Street; a battalion on the right managed a small advance.[53]

On 30 July, subsidiary attacks were made at Delville Wood and Longueval, in support of a bigger attack to the south by XIII Corps and XX Corps. The 5th Division attacked with the 13th Brigade, to capture German strong-points north of the village and the south-eastern end of Wood Lane. A preliminary bombardment began at 4:45 p.m. but failed to suppress the German artillery, which fired on the village and the wood. British communications were cut again, as two battalions advanced at 6:10 p.m.; the right-hand battalion was caught by German artillery-fire, at the north-west fringe of the wood but a company pushed on and dug in beyond. The left-hand battalion crawled forward under the British barrage but as soon as it attacked, massed German small-arms fire forced the troops under cover in shell-holes. A battalion on the right with only 175 men was so badly shelled, that a battalion was sent forward and a reserve battalion of the 15th Brigade was also sent forward. Attempts were made to reorganise the line in Longueval, where many units were mixed up; German artillery-fire was continuous and after dark the 15th Brigade took over.[54] After representations by Major-General R. B. Stephens it was agreed that the 5th Division would be relieved during 1 August.[55]

A lull occurred in early August, as the 17th Division took over from the 5th Division; the 52nd Brigade was ordered to attack Orchard Trench, which ran from Wood Lane to North Street and the Flers Road into Delville Wood. A slow bombardment by heavy artillery and then a five-minute hurricane bombardment was followed by the attack at 12:40 a.m. on 4 August. Both battalions were stopped by German artillery and machine-gun fire; communications were cut and news of the costly failure was not reported until 4:35 a.m. The 17th Division took over from the 2nd Division on the right and attacked again on 7 August, after a methodical bombardment, assisted by a special reconnaissance and photographic sortie by the RFC. The 51st Brigade attacked at 4:30 p.m., to establish posts beyond the wood but the British were stopped by German artillery-fire while still inside. After midnight, a fresh battalion managed to establish posts north of Longueval. German defensive positions in the area appeared much improved and the 17th Division was restricted to obtaining vantage points, before it was relieved by the 14th Division on 12 August.[56]

XV Corps attacked again on 18 August; in Delville Wood, the 43rd Brigade of the 14th Division, attacked the north end of ZZ Trench, Beer Trench up to Ale Alley, Edge Trench and a sap along Prince's Street, which had been found on reconnaissance photographs. The right-hand battalion advanced close behind a creeping barrage at 2:45 p.m., reached the objective with few losses where the defenders surrendered. The south of Beer Trench was obliterated but the left-hand battalion was swept by artillery and machine-guns before the advance and reduced to remnants. The battalion took Edge Trench and bombed along Prince's Street, when German supports bombed down Edge Trench and retook it. In hand-to-hand fighting, the British held on to Hop Alley and blocked Beer Trench; two German attacks from Pint Trench were stopped by small-arms fire. During the British attack, the German line from Prince's Street to the Flers road, was bombarded by trench-mortars. On the left, two battalions of the 41st Brigade attacked Orchard Trench and the south end of Wood Lane; keeping touch with an attack by the 33rd Division on High Wood. The battalion on the right advanced close up to the creeping barrage, found Orchard Trench nearly empty and dug in beyond, with the right flank on the Flers road. The left-hand battalion was enfiladed from the left flank, after the 98th Brigade of the 33rd Division was repulsed but took part of Wood Lane.[57]

21 August – 3 September

On 21 August, a battalion of the 41st Brigade attacked the German defences in the wood, obscured by smoke discharges on the flanks but the German defenders inflicted nearly 200 casualties by small-arms fire. At midnight, an attack by the 100th Brigade of the 33rd Division, from the Flers road to Wood Lane began but the right-hand battalion was informed too late and the left-hand battalion attacked alone and was repulsed.[58] In a combined attack with the French from the Somme north to the XIV Corps and III Corps areas, XV Corps attacked to complete the capture of Delville Wood and consolidate from Beer Trench to Hop Alley and Wood Lane. The 14th Division operation was conducted by a battalion of the 41st Brigade and three from the 42nd Brigade.[59]

The right hand battalion was repulsed at Ale Alley but the other battalions, behind a creeping barrage moving in lifts of only 25 yd (23 m), advanced through the wood until their right flank was exposed, which prevented most of Beer Trench from being occupied. On the left flank, the westernmost battalion dug in on the final objective and gained touch with the 33rd Division on the Flers road. The new line ran south, from the right of the battalion near the Flers road, into the wood and then south-east along the edge to Prince's Street. Flares were lit for contact-aeroplanes, which were able to report the new line promptly. Over 200 prisoners and more than twelve machine-guns were captured.[59]

Early next day, a battalion of the 42nd Brigade captured Edge Trench, to a point close to the junction with Ale Alley. Amidst rain delays, the 7th Division relieved the right-hand brigade of the 14th Division on the night of 26/27 August and later a battalion of the 43rd Brigade made a surprise attack, took the rest of Edge Trench and barricaded Ale Alley, taking about 60 prisoners from Infantry Regiment 118 of the 56th Division, which eliminated the last German foothold in Delville Wood. An attack on the evening of 28 August, by a battalion on the right flank and a battalion of the 7th Division to the right, from the east end of the wood, against Ale Alley to the junction with Beer Trench failed. The 14th and 33rd divisions were relieved by the 24th Division by the morning of 31 August, after the 42nd Brigade had built posts along the wreckage of Beer Trench as far as the south-east of Cocoa Lane and dug a sap from the end of Prince's Street. The last week of August had been very wet, which made patrolling even more difficult but XV Corps detected the arrival of German reinforcements. The activity of the German artillery around Delville Wood suggested another counter-attack was imminent, as the 24th Division took over the defence of the wood and Longueval. German aircraft flew low over the British front positions and then a much more intense bombardment began.[60]

The German attack began at 1:00 p.m. and the 7th Division on the right of the corps, was attacked along Ale Alley and Hop Alley and replied with rapid fire. The German infantry were repulsed but a second attack at 2:00 p.m. was only held after hand-to-hand fighting just east of the wood. More German aircraft reconnoitred the area and German artillery-fire greatly increased around 4:30 p.m., followed by a third attack at 7:00 p.m., which pushed the British back into the wood, except on the left at Edge Trench. On the right flank, the Ginchy–Longueval road was held against the German attacks and some reinforcements arrived after dark, at the east end of the wood. At the north-east side, the right-hand battalion of the 72nd Brigade had moved forward, to dig in beyond the German bombardment and was not attacked; the left-hand battalion withdrew its right flank to Inner Trench to evade the bombardment and a strong point on Cocoa Lane was captured.[61]

The left flank of the battalion and the neighbouring right-hand battalion of the 73rd Brigade, were attacked at 1:00 p.m. and repulsed the German infantry and Stoßtruppen with small-arms and artillery-fire. To the west, the left-hand battalion was caught in the German bombardment and lost nearly 400 men. German infantry advanced from Wood Lane and bombed along Tea Trench almost as far as North Street. Other German troops attacked south-east into Orchard Trench, before British reinforcements arrived and contained the German advance, with the help of flanking fire from the 1st Division beyond the III Corps boundary. It was not until long after dark, that the extent of the German success was communicated to the XV Corps headquarters, where plans were made to recapture the ground next day.[62]

A battalion from the 73rd Brigade of the 24th Division counter-attacked at dawn by bombing along Orchard Trench but was repulsed by the German defenders. More bombers attacked around Pear Street at 9:50 a.m. but were also repulsed. A costly frontal attack by a battalion of the 17th Brigade at 6:30 p.m., overran Orchard Trench and Wood Lane up to Tea Trench. On the east side of the wood, two platoons from the 91st Brigade attacked at 5:00 a.m. but were forced back by small arms fire and at 3:00 p.m. a battalion of the 24th Division managed to bomb a short way down Edge Trench, which was almost invisible after the recent bombardments. On 1 September, the battalion attacked again but made little progress against German bombers and snipers.[63]

The 7th Division was due to attack Ginchy on 3 September but the Germans in Ale Alley, Hop Alley and the east end of Delville Wood commanded the ground over which the attack was to cross. A preliminary attack was arranged with the 24th Division, to begin five minutes before the main attack to recapture the ground. The 7th Division bombers used "fumite" grenades but these were too easy to see and alerted the German defenders and the 24th Division battalion received such contradictory orders that its attack north of Ale Alley failed.[64] Attacks on 4 September by two companies at the east end of the wood also failed and next day two companies managed to reach the edge of the wood close to Hop Alley and dig in. On the night of 5 September, the 24th Division was relieved by the 55th Division and the 166th Brigade dug in beyond the north-east fringe of the wood unopposed.[65]

Air operations

The first attack on Longueval and Delville Wood from 14–15 July, was conducted under the observation of 9 Squadron, which directed counter-battery artillery-fire, photographed the area and flew contact-patrols to report the positions of infantry. During the morning a patrol of F.E. 2bs from 22 Squadron escorted the corps aircraft but no German aeroplanes were seen.[lower-alpha 4] The British aircraft carried new "Buckingham" tracer ammunition, which made aiming easier and began to attack German targets on the ground. The crews machine-gunned German infantry near Flers, cavalry sheltering under trees and other parties of German troops to the south-west.[67] During the XV Corps attacks on 24 August, 3 Squadron aircraft brought back detailed information about the progress of the infantry, who had lit many red flares when called on by contact-aircraft. Fourteen flares were seen by an observer at 6:40 p.m. to the north of the wood, which showed that the troops had overrun their objective and were under shrapnel fire from British artillery. The information was taken back and dropped by message-bag, which got the barrage lifted by 100 yd (91 m). The crew returned to the wood, completed the contact-patrol and reported to the XV Corps headquarters by 8:00 p.m., showing that the 14th Division was held up on the east side of the wood. A further attack the following morning captured the area, which was closely observed by British aircraft.[68]

German 2nd Army

14–19 July

| Date | Rain mm |

°F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0 | 82°–59° | hot |

| 2 | 0.0 | 88°–57° | hot |

| 3 | 0.0 | 84°–57° | hot |

| 4 | 0.0 | 79°–52° | — |

| 5 | 0.0 | 68°–48° | fine |

| 6 | 0.0 | 75°–52° | — |

| 7 | 0.0 | 73°–50° | — |

| 8 | 0.0 | 77°–52° | — |

| 9 | 0.0 | 84°–54° | — |

| 10 | 4.0 | 70°–55° | dull |

| 11 | 0.0 | 77°–59° | rain |

| 12 | 1.0 | 82°–63° | — |

| 13 | 0.0 | 81°–59° | wind |

| 14 | 2.0 | 77°–59° | rain |

| 15 | 0.0 | 75°–55° | rain |

| 16 | 2.0 | 75°–55° | — |

| 17 | 4.0 | 72°–54° | rain |

| 18 | 1.0 | 70°–55° | dull |

| 19 | 2.0 | 70°–50° | dull |

| 20 | 0.0 | 72°–54° | dull |

| 21 | 0.0 | 72°–48° | — |

| 22 | 0.0 | 72°–52° | — |

| 23 | 0.0 | 72°–54° | — |

| 24 | 0.0 | 78°–55° | — |

| 25 | 8.0 | 81°–61° | dull |

| 26 | 7.0 | 75°–59° | — |

| 27 | 4.0 | 73°–59° | — |

| 28 | 0.1 | 73°–59° | rain |

| 29 | ? | 82°–59° | rain |

| 30 | 8.0 | 63°–48° | mud |

| 31 | 0.0 | 70°–52° | fine |

| 1 | 0.0 | 72°–52° | — |

| 2 | 0.0 | 75°–52° | wind |

| 3 | 4 | 72°–50° | — |

| 4 | 25 | 66°–52° | rain |

| 5 | 0.0 | 63°–54° | dull |

| 6 | 0.0 | 70°–52° | dull |

According to the German official history, Der Weltkrieg and regimental accounts, some units were not surprised. The British attack succeeded at a few points, from which the troops worked sideways to roll up the German defenders, a tactic not used on 1 July. Bavarian Infantry Regiment 16 lost c. 2,300 men and the headquarters of Infantry Regiment Lehr, Bavarian Infantry Regiment 16, I Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 91 and II Battalion, Bavarian Infantry Regiment 16 were captured. Armin, who had taken over from Longueval to the Ancre that morning, ordered troops to hold their positions. The 7th Division had been relieving the 183rd Division and part was sent to Longueval and the second line further back, along with resting units from the 185th, 17th Reserve, 26th Reserve, 3rd Guard divisions and troops of the 55th Landwehr Regiment (7th Landwehr Division), equivalent to fourteen battalions. After alarmist reports of British cavalry in High Wood and the fall of Flers and Martinpuich, Below ordered the 5th, 8th, 8th Bavarian Reserve and 24th Reserve divisions to counter-attack to stop the British advance. When the true situation was discovered, the counter-stroke was cancelled and the 5th and 8th divisions returned to reserve.[70]

On 15 July, II Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 107 of the 24th Reserve Division attacked from the south-east of Delville Wood at about 11:30 a.m. but was stopped by small-arms and artillery-fire 80 yd (73 m) short of the wood and driven under cover. An attack by the III Battalion from the Flers–Ginchy road soon after, was also stopped short and the battalions lost 528 men. I Battalion, Infantry Regiment 72 from the 8th Division attacked the north-eastern face of the wood and was also repulsed. Armin ordered another attack after dark by the 8th Division and 12th Reserve Division, to take back the wood at all costs. The preparations were rushed and no postponement was allowed; a bombardment began at 9:00 p.m., before the advance began around midnight by I and II battalions of Infantry Regiment 153 from the 8th Division and II Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 107 of the 12th Reserve Division, on the east, north-east and northern faces of the wood, which also failed against artillery and machine-gun fire, 50 yd (46 m) short of the wood, after which German artillery bombarded the wood all night. Further attempts to regain the wood on 16 July were also costly failures.[71]

The 8th Division planned to recapture Delville Wood on 18 July and the most advanced troops were withdrawn late on 17 July, for a bombardment which began at 11:45 p.m., using the heavy guns of groups Von Gossler and Von Armin, the field artillery of the 8th Division and three batteries of the 12th Reserve Division, about 116 field guns and 70 medium guns, heavy guns and howitzers.[72] The German bombardment turned Delville Wood into an "inferno", before slackening at around 3:45 a.m. during a British attack. After 3:30 p.m., German troops from I Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 104 and II and III battalions, Reserve Infantry Regiment 107, attacked the wood in several waves from the north-east, as eight companies of Infantry Regiment 153 of the 8th Division attacked from the north, to reach a line from Longueval to Waterlot Farm road. Another attack from the north and north-west by five companies of Infantry Regiment 26 of the 7th Division, reached the southern edge of the village.[73]

The attacks were not co-ordinated but were led by companies of Stoßtruppen (Storm Troop) and flammenwefer (Flamethrower) detachments, which fell into confusion in the wood; after dark parts of II Battalion, Infantry Regiment 52 of the 5th Division reinforced the troops in the wood and the village. On 19 July, the Germans in the wood endured massed British artillery-fire; Infantry Regiment 52 and part of Grenadier Regiment 12 were sent into the wood and the village, where Infantry Regiment 26 had appealed for relief before it collapsed. A British attack early on 20 July reached the village, where two companies were overwhelmed and 82 prisoners taken. By 20 July, Infantry Regiment 26, which had been at full strength on 13 July, was reduced to 360 men and with Infantry Regiment 153, was relieved by Grenadier Regiment 12, which held Delville Wood and Longueval with Infantry Regiment 52, under the command of the 5th Division.[74]

German 1st Army

20 July – 3 September

The German defence of the Somme was reorganised in July and the troops of the Second Army north of the Somme were transferred to the command of a re-established 1st Army under the command of Below, overseen by General von Gallwitz the new commander of the 2nd Army and armeegruppe Gallwitz-Somme.[75] During a British attack on 23 July the 5th Division had to engage nearly all of its troops to resist the attack, which threw the defence into confusion. In anticipation of more British attacks a box-barrage was fired around the village and wood. 163 prisoners of Grenadier Regiment 8 were taken in a British attack on 27 July, one prisoner calling it the worst shelling he had endured. At 9:30 a.m., German troops were seen massing for a counter-attack and managed to advance through a British protective artillery barrage, to engage the British infantry in a bombing fight. The German attack took part of the east end of the wood but the exhaustion of the 5th Division, which had been reduced to a "pitiable state", required reinforcement by three battalions, mainly from the 12th Division, from 27–29 July.[53]

On 30 July, British artillery-fire caused many casualties and the right flank of the 5th Division was hurriedly reinforced by I Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 163 of the 17th Reserve Division, sent from Ytres, which was spotted by British aircrews at Beaulencourt and shelled. During the night II Battalion, Infantry Regiment 23 of the 12th Division was relieved by the I Battalion.[54] On 4 August, a British attack began as the Fusilier Battalion of Grenadier Regiment 12 was being relieved by I Battalion, Infantry Regiment 121 of the 26th Division, which was taking over from the 5th Division, Grenadier Regiment 119 coming into line to the east. A general relief of the German troops on the Somme front was conducted, as the British artillery kept up a steady bombardment of Delville Wood and German observation balloons began to operate between Ginchy and the wood.[76]

On 18 August, Infantry Regiment 125 of the 27th Division was surprised by an attack from the east end of Delville Wood, after its trenches were almost obliterated by British artillery. The British infantry arrived as soon as the barrage lifted and Grenadier Regiment 119 to the north, was almost rolled up from its left flank but two companies of III Battalion counter-attacked through I Battalion, which had lost too many men to participate. At the north-west side of the wood, Infantry Regiment 121 of the 26th Division found that the British artillery had made Orchard Trench almost untenable. II Battalion had to advance through the shell-fire and dig a new line behind Orchard Trench, to maintain touch with the flanks, before being relieved by I Battalion overnight.[77] The trench was occupied by Infantry Regiment 104 of the 40th Division, from North Street to the west and by Infantry Regiment 121 north of Longueval, which repulsed an attack on 21 August.[58]

Another British attack came on 24 August, as Infantry Regiment 88 from the 56th Division began to relieve Infantry Regiment 121 and Grenadier Regiment 119. Every man left in the regiment was needed to withstand the attack, which caused the loss of more than 200 prisoners and twelve machine-guns. After the attack, Fusilier Regiment 35 of the 56th Division relieved Infantry Regiment 125, which called the days on the Somme "the worst in the war". II Battalion, Infantry Regiment 181 was sent as a reinforcement and one of its companies was annihilated. An attempted counter-attack by the battalion and part of Infantry Regiment 104, was smashed by British artillery-fire and a German counter-bombardment hampered British consolidation.[78] On 27 August, the German garrison in Edge Trench, the last foothold in Delville Wood, was driven out and Infantry Regiment 118 lost 60 prisoners.[58] A counter-attack to recover the wood was made possible by the arrival of a wave of fresh German divisions on the Somme and in late August, German artillery preparation began for an attack on 31 August.[58]

The 4th Bavarian and 56th divisions were to make a pincer attack at 2:15 p.m. on the east and north sides of the wood, with I Battalion, Bavarian Infantry Regiment 5, III Battalion, Fusilier Regiment 35 and II Battalion, Infantry Regiment 88. Each battalion attacked with two companies forward and two in support. Jäger Battalion 3, was one of the first to be trained and equipped as a specialist assault unit; training had begun in mid-June, after large numbers of unfit men had been transferred to other units. Fitness training and familiarisation with light mortars and flame-throwers had been provided and the unit arrived on the Somme on 20 August. Parts of the unit began demonstrations and training courses in the new tactics and the 1st and 2nd companies were attached to the Bavarian and Fusilier battalions, which were to retake Delville Wood.[79] The attack began after a bombardment from 10:00 a.m., which had little effect on the British defences.[80]

At the east end of the wood, Fusilier Regiment 35 attacked with the support of flame-thrower detachments but the mud was so bad that six became unusable, the artillery preparation was inadequate and the first two attacks failed. The third attempt, after a more extensive bombardment, was called "a wonderful victory". The attack from the north came from three companies of Infantry Regiment 88 and Stormtroops either side of Tea Lane. British return fire caused many casualties and forced the attackers to move from shell-hole to shell-hole, eventually being pinned down in no man's land. The survivors withdrew after dark, rallying at Flers. I Battalion, Bavarian Infantry Regiment 5, with a company of Jäger Battalion 3, attached flame-thrower and bombing detachments, attacked eastwards towards the 56th Division, along Tea and Orchard trenches, where a bomber killed a British machine-gun crew, by throwing a grenade 60 metres (66 yd). A second artillery bombardment was fired at 5:00 p.m., and the Jäger managed to take 300 prisoners and gain a foothold. The position in the wood was abandoned by the Jäger, because the repulse of the 56th Division units, left them isolated and under increasing artillery-fire.[81]

Aftermath

Analysis

Lukin had wanted to defend Delville Wood with machine-guns and small detachments of infantry but prompt German counter-attacks prevented this; Tanner had needed every man for the defence.[82] The British had eventually secured Longueval and Delville Wood in time for the formations to their north to advance and capture High Wood ready for the Flers–Courcelette and the later Somme battles. Over the southern part of the British front, there had been c. 23,000 casualties for a small "tongue" of ground a few miles deep.[83] The Allies and Germans suffered many casualties in continuous piecemeal attacks and counter-attacks. Gallwitz recorded that from 26 June – 28 August, 1,068 field guns of the 1,208 on the Somme had been destroyed, captured or made unserviceable, along with 371 of the 820 heavy guns.[8]

In 2005, Prior and Wilson wrote that an obvious British remedy to the salient at Delville Wood was to move the right flank forward, yet only twenty attacks were made in this area, against 21 at the wood and 29 further to the left. The writers held that British commanders had failed to command and had neglected the troops who were frittered away, such that the attrition of British forces was worse than the effect on the Germans. It was speculated that this was perhaps a consequence of the inexperience of Haig and Rawlinson in handling forces vastly larger than the British peacetime army. Prior and Wilson also wrote that 32 British divisions engaged 28 German divisions, most of which suffered casualties greater than 50 percent, due to the 7,800,000 shells fired by the British from 15 July – 12 September, despite shell-shortages and problems in transporting ammunition when rain had soaked the ground. German failings were also evident, particularly in counter-attacking to regain all lost ground, even when of little tactical value, which demonstrated that commanders on both sides had failed to control the battle.[84]

In 2009, J. P. Harris wrote that during the seven weeks' battle for control of Delville Wood, the infantry on both sides endured what appeared to be a bloody and frustrating stalemate, which was even worse for the Germans. The greater amount of British artillery and ammunition was directed by RFC artillery-observers in aircraft and balloons, which increased the accuracy of fire despite the frequent rain and mist. German counter-attacks were tactically unwise and exposed German infantry to British fire power regardless of the value of the ground being attacked. In the Fourth Army sector, the Germans counter-attacked seventy times from 15 July – 14 September against ninety British attacks, many in the vicinity of Delville Wood. The British superiority in artillery was often enough to make costly failures of the German efforts and since German troops were relieved less frequently, the constant British bombardments and loss of initiative depressed German morale.[85]

By the end of July, the German defence north of the Somme had reached a point of almost permanent collapse; on 23 July, the defence of Guillemont, Delville Wood and Longueval almost failed and from 27 to 28 July, contact with the defenders of the wood was lost; on 30 July another crisis occurred between Guillemont and Longueval. Inside the flanks of the German first position, troops occupied shell-holes to evade bombardment by the British artillery, which vastly increased the strain on the health and morale of the troops, isolated them from command, made it difficult to provide supplies and to remove wounded. Corpses strewed the landscape, fouled the air and reduced men's appetites even when cooked food could be brought from the rear; troops in the most advanced positions lived on tinned food and went thirsty. From 15 to 27 July, the 7th and 8th divisions of IV Corps, from Delville Wood to Bazentin le Petit suffered 9,494 casualties.[86]

The Battle for Longueval and Delville Wood, had started with a charge by the 2nd Indian Cavalry Division between Longueval and High Wood and two weeks after the wood was cleared, tanks went into action for the first time. A number of important tactical lessons were learned from the battle for the village and wood. Night assembly and advances, dawn attacks after short, concentrated artillery barrages for tactical surprise nd building defensive lines on the fringes of wooded areas, to avoid tree roots in preventing digging and to keep clear of shells which were detonated by branches, showering troops with wood splinters. Troops were relieved after two days, as longer periods exhausted them and consumed their ammunition, bombs and rations.[87] The persistence of the British attacks during July and August helped to preserve Franco-British relations, although Joffre criticised the large number of small attacks on 11 August and tried to cajole Haig into agreeing to a big combined attack. On 18 August, a larger British attack by three corps was spoilt by several days of heavy rain, which reduced artillery observation and no ground was gained at Delville Wood.[88]

Casualties

Another forty-two German divisions fought on the Somme front in July and by the end of the month German losses had increased to c. 160,000 men; the number of Anglo-French casualties was more than 200,000.[89] The battle for Delville Wood was costly for both sides and the 9th (Scottish) Division had 7,517 casualties from 1 to 20 July, of which the 1st (South African) Infantry Brigade lost 2,536 men.[90] [lower-alpha 5] From 11 to 27 July the 3rd Division had 6,102 casualties.[48] The 5th Division lost c. 5,620 casualties from 19 July to 2 August and the 17th Division had 1,573 casualties from 1 to 13 August.[56] The 8th Division lost 2,726 casualties from 14 to 21 July.[74] The 14th Division lost 3,615 casualties and the 33rd Division lost 3,846 men in August and from the end of August to 5 September, the 24th Division had c. 2,000 casualties.[94]

Details of German losses are incomplete, particularly for Prussian divisions, due to the loss of records to Allied bombing in the Second World War.[95] From 15 to 27 July the 7th and 8th divisions of IV Corps held the line from Delville Wood to Bazentin le Petit and suffered 9,494 casualties. The 5th Division was not relieved from Delville Wood until 3 August and lost c. 5,000 casualties a greater loss than at Verdun in May.[86] Infantry Regiment 26, which had been at full strength on 13 July was reduced 260 men on 20 July.[90] The British official historian, Wilfrid Miles, wrote that many German divisions returned from a period on the Somme with losses greater than c. 4,500 men.[8] Bavarian Infantry Regiment 5 of the 4th Bavarian Division recorded "the loss of many good, irreplaceable men".[96]

Subsequent operations

The Battle of Flers–Courcelette (15–22 September) was the third British general offensive during the Battle of the Somme and continued the advance from Delville Wood and Longueval. The battle was notable for the first use of tanks and the capture of the villages of Courcelette, Martinpuich and Flers. In the XV Corps area, the 14th (Light) Division on the right advanced to the area of Bull's Road between Flers and Lesbœufs, in the centre the 41st Division, the newest division in the BEF, captured Flers with the help of tank D-17 and the New Zealand Division, between Delville Wood and High Wood on the left, took the Switch Line, linking with the 41st Division in Flers, after two tanks arrived and the German defenders were overrun. The Fourth Army made a substantial advance of 2,500–3,500 yd (1.4–2.0 mi; 2.3–3.2 km) but failed to reach the final objectives.[97]

The Allies held the Wood until 24 March 1918, when the 47th Division received orders to retire with the rest of V Corps, after German troops broke through the junction of V Corps and VII Corps. British and German soldiers sometimes found themselves marching parallel, as the British troops fell back and formed a new line facing south between High Wood and Bazentin le Grand.[98] On 29 August 1918, the 38th (Welsh) Division attacked at 5:30 a.m., to take the high ground east of Ginchy and then capture Delville Wood and Longueval from the south. The 113th Brigade was virtually unopposed and reached the objective by 9:00 a.m. and the 115th Brigade advanced north of the wood, which was mopped up by the 114th Brigade. Later in the day, the advance reached the vicinity of Morval.[99] The Armistice with Germany ended hostilities three months later.[100]

See also

Victoria Cross

- Private William Frederick Faulds on 18 July: 1st Battalion, 1st South African Brigade, 9th Scottish Division.[90]

- Corporal Joseph John Davies on 20 July: 10th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers, 76th Brigade, 3rd Division[90]

- Private Albert Hill on 20 July: 10th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers, 76th Brigade, 3rd Division.[90]

- Major W. la Touche Congreve 20 July, Brigade Major 76th Brigade, 3rd Division.[90]

- Sergeant Albert Gill on 27 July: 1st Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps, 99th Brigade, 2nd Division.[53]

Notes

- Falkenhayn implied after the war that the psychology of German soldiers, shortage of manpower and lack of reserves made the policy inescapable, since the troops necessary to seal off breakthroughs did not exist. High losses incurred in holding ground by a policy of no retreat, were preferable to higher losses, voluntary withdrawals and the effect of a belief that soldiers had discretion to avoid battle. When a more flexible policy was substituted later, discretion was still reserved to army commanders.[18]

- Known as Maltzhorn Farm to the Germans and locals, but listed on the British 1:10,000 map for Longueval (Ed 2.E 15 August 1916) as Warterlot Farm. The farm contained a large sugar mill which provided good cover for sniping and artillery observation and was thus considered to be of tactical importance, joining up with the 9th Division which was holding the southern half of Longueval.[33]

- Each corps was expected to have 100 × field guns and 100 × medium and heavy artillery pieces. German positions on the flanks were to be engaged by the French XX Corps and the 35th Division from Guillemont to Ginchy and Flers, as the 9.2-inch and 12-inch guns of III Corps bombarded German-occupied villages further back. The one-hour bombardment was to become intense for the last seven minutes before zero hour and before each lift; the barrage was to move forward through the wood and village in three lifts, with intervals of one hour and then thirty minutes. The artillery was then to form a standing barrage beyond the final objective, for as long as necessary and the field gunners were to use as much High Explosive (H.E.) shell as possible. The two British corps amassed 369 guns and howitzers for the bombardment, excluding counter-battery artillery.[50]

- From 30 January 1916, each British army had a Royal Flying Corps brigade attached, which was divided into wings, the "corps wing" with squadrons responsible for close reconnaissance, photography and artillery observation on the front of each army corps and an "army wing" which conducted longer-range reconnaissance and bombing, using the aircraft types with the highest performance.[66]

- South African Brigade losses in Delville Wood have been exaggerated by mistakenly adding casualties at Bernafay Wood and Maricourt suffered before 14 July and those of the 1st and 4th Battalions in Longueval on 14 July.[91] Of the three officers and 140 men who left Delville Wood on 20 July, fewer than half had entered the wood on 14/15 July and rest were the survivors of 199 replacements who had arrived from 16 to 20 July.[92] The Brigade headquarters and staff had not entered the wood and more troops reported to Happy Valley, for the muster parade of 21 July along with Brigade and Machine Gun Company staff.[93]

Footnotes

- Buchan 1926, p. 82.

- Buchan 1920, p. 49.

- Buchan 1920, pp. 52–54.

- Miles 1938, p. 27.

- Sheldon 2005, p. 179.

- Miles 1938, p. 173.

- Miles 1938, p. 118.

- Miles 1938, p. 229.

- Miles 1938, p. 230.

- Miles 1938, pp. 4–61.

- Sheffield 2003, pp. 79–84.

- Gliddon 1987, p. 276.

- Uys 1986, p. 49.

- Gliddon 1987, p. 125.

- Ewing 1921, p. 102.

- Ewing 1921, p. 103.

- Buchan 1920, pp. 52–58.

- Sheldon 2005, p. 223.

- Wynne 1939, pp. 100–101.

- Nasson 2007, p. 133.

- Uys 1991, p. 96.

- Miles 1938, p. 89.

- Philpott 2009, p. 256.

- Philpott 2009, pp. 255–256.

- Philpott 2009, pp. 259–260.

- Digby 1993, p. 123.

- Miles 1938, p. 92.

- Buchan 1920, pp. 59–63.

- Uys 1983, p. 71.

- Uys 1983, p. 72.

- Nasson 2007, p. 131.

- Uys 1983, p. 103.

- Buchan 1920, pp. 64–65.

- Uys 1983, pp. 103–104.

- Buchan 1920, pp. 64–69.

- Uys 1983, p. 135.

- Buchan 1920, pp. 70–75.

- Uys 1983, p. 204.

- Rogers 2010, p. 111.

- Uys 1983, p. 205.

- Uys 1991, p. 102.

- Nasson 2007, pp. 134–135.

- Uys 1991, p. 113.

- Uys 1991, p. 117.

- Buchan 1920, p. 72.

- Gliddon 1987, pp. 415–417.

- Miles 1938, p. 141.

- Miles 1938, p. 157.

- Miles 1938, p. 158.

- Miles 1938, pp. 157–158.

- Miles 1938, pp. 158–159.

- Miles 1938, pp. 158–160.

- Miles 1938, p. 160.

- Miles 1938, p. 167.

- Miles 1938, p. 170.

- Miles 1938, pp. 185–186.

- Miles 1938, pp. 193–194.

- Miles 1938, p. 199.

- Miles 1938, pp. 201–202.

- Miles 1938, pp. 201–205.

- Miles 1938, pp. 205–206.

- Miles 1938, pp. 206–207.

- Miles 1938, pp. 250–251.

- Miles 1938, pp. 262–263.

- Miles 1938, pp. 265–269.

- Jones 1928, pp. 147–148.

- Jones 1928, pp. 230–231.

- Jones 1928, pp. 245–246.

- Gliddon 1987, pp. 417–419.

- Miles 1938, pp. 88–89.

- Miles 1938, pp. 92–93.

- Miles 1938, p. 94.

- Miles 1938, p. 105.

- Miles 1938, p. 106.

- Miles 1938, pp. 117–118.

- Miles 1938, pp. 186–187.

- Miles 1938, p. 194.

- Miles 1938, pp. 199, 202.

- Sheldon 2005, pp. 258.

- Sheldon 2005, pp. 257–258.

- Sheldon 2005, pp. 259–260.

- Ewing 1921, p. 121.

- Liddell Hart 1970, p. 326.

- Prior & Wilson 2005, pp. 188–190.

- Harris 2008, p. 256.

- Miles 1938, p. 172.

- Uys 1991, pp. 159–165.

- Harris 2008, p. 257.

- Keegan 1998, p. 319.

- Miles 1938, p. 108.

- Uys 1991, pp. 192–194, 274.

- Uys 1991, p. 187.

- Uys 1991, pp. 194–198.

- Miles 1938, p. 205.

- Sheldon 2005, p. 407.

- Miles 1938, p. 277.

- Sheffield 2003, pp. 117–120.

- Davies, Edmonds & Maxwell-Hyslop 1935, pp. 427–433.

- Edmonds 1947, pp. 343–344.

- Uys 1991, p. 122.

References

Books

- Buchan, J. (1996) [1926]. Homilies and Recreations (Naval & Military Press ed.). Freeport: Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 0-8369-1172-5.

- Buchan, J. (1992) [1920]. The History of the South African Forces in France (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Nelson. ISBN 0-901627-89-5. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- Digby, P. K. A. (1993). Pyramids and Poppies: The 1st SA Infantry Brigade in Libya, France and Flanders: 1915–1919. South Africans at War. 11. Rivonia: Ashanti. ISBN 1-874800-53-7.

- Davies, C. B.; Edmonds, J. E.; Maxwell-Hyslop, R. G. B. (1995) [1935]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: The German March Offensive and its Preliminaries. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-219-5.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1947]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: 8th August – 26th September, The Franco-British Offensive. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. IV (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-191-1.

- Ewing, J. (2001) [1921]. The History of the Ninth (Scottish) Division 1914–1919 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 1-84342-190-9. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- Gliddon, G. (1987). When the Barrage Lifts: A Topographical History and Commentary on the Battle of the Somme 1916. Norwich: Gliddon Books. ISBN 0-947893-02-4.

- Harris, J. P. (2009) [2008]. Douglas Haig and the First World War (pbk. ed.). Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-89802-7.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force. II (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 1-84342-413-4. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- Keegan, J. (1998). The First World War. London: Random House. ISBN 0-09-180178-8.

- Liddell Hart, B. H. (1970). History of the First World War (3rd ed.). Trowbridge: Redwood Burn. ISBN 0-33023-770-5.