Oriental rug

An oriental rug is a heavy textile made for a wide variety of utilitarian and symbolic purposes and produced in “Oriental countries” for home use, local sale, and export.

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

| Architecture |

| Art |

|

| Dress |

| Holidays |

|

| Literature |

|

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

Oriental carpets can be pile woven or flat woven without pile, using various materials such as silk, wool, and cotton. Examples range in size from pillow to large, room-sized carpets, and include carrier bags, floor coverings, decorations for animals, Islamic prayer rugs ('Jai'namaz'), Jewish Torah ark covers (parochet), and Christian altar covers. Since the High Middle Ages, oriental rugs have been an integral part of their cultures of origin, as well as of the European and, later on, the North American culture.[1]

Geographically, oriental rugs are made in an area referred to as the “Rug Belt”, which stretches from Morocco across North Africa, the Middle East, and into Central Asia and northern India. It includes countries such as northern China, Tibet, Turkey, Iran, the Maghreb in the west, the Caucasus in the north, and India and Pakistan in the south. Oriental rugs were also made in South Africa from the early 1980s to mid 1990s in the village of Ilinge close to Queenstown.

People from different cultures, countries, racial groups and religious faiths are involved in the production of oriental rugs. Since many of these countries lie in an area which today is referred to as the Islamic world, oriental rugs are often also called “Islamic Carpets”,[2] and the term “oriental rug” is used mainly for convenience. The carpets from Iran are known as “Persian Carpets”.[3]

In 2010, the “traditional skills of carpet weaving” in the Iranian province of Fārs,[4] the Iranian town of Kashan,[5] and the “traditional art of Azerbaijani carpet weaving” in the Republic of Azerbaijan"[6] were inscribed to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.

The origin of the knotted pile rug

The beginning of carpet weaving remains unknown, as carpets are subject to use, deterioration, and destruction by insects and rodents. There is little archaeological evidence to support any theory about the origin of the pile-woven carpet. The earliest surviving carpet fragments are spread over a wide geographic area, and a long time span. Woven rugs probably developed from earlier floor coverings, made of felt, or a technique known as “extra-weft wrapping”.[7][8] Flat-woven rugs are made by tightly interweaving the warp and weft strands of the weave to produce a flat surface with no pile. The technique of weaving carpets further developed into a technique known as extra-weft wrapping weaving, a technique which produces soumak, and loop woven textiles. Loop weaving is done by pulling the weft strings over a gauge rod, creating loops of thread facing the weaver. The rod is then either removed, leaving the loops closed, or the loops are cut over the protecting rod, resulting in a rug very similar to a genuine pile rug.[9] Typically, hand-woven pile rugs are produced by knotting strings of thread individually into the warps, cutting the thread after each single knot. The fabric is then further stabilized by weaving (“shooting”) in one or more strings of weft, and compacted by beating with a comb. It seems likely that knotted-pile carpets have been produced by people who were already familiar with extra-weft wrapping techniques.[10]

Historical evidence from ancient sources

Probably the oldest existing texts referring to carpets are preserved in cuneiform writing on clay tablets from the royal archives of the kingdom of Mari, from the 2nd millennium BC. The Akkadian word for rug is mardatu, and specialist rug weavers referred to as kāşiru are distinguished from other specialized professions like sack-makers (sabsu or sabsinnu).[11]

"To my Lord speak! Your servant Ašqudum (says), I've requested a rug from my lord, and they did not give me (one). [...]" (letter 16 8)

"To my Lord speak! Your servant Ašqudum (says), About the woman who is staying by herself in the palace of Hişamta—The matter does not meet the eye. It would be good if 5 women who weave carpets[12] were staying with her." (letter 26 58)— Litteratures anciennes du proche-Orient, Paris, 1950[13]

Palace inventories from the archives of Nuzi, from the 15th/14th century BC, record 20 large and 20 small mardatu to cover the chairs of Idrimi.[14]

There are documentary records of carpets being used by the ancient Greeks. Homer writes in Ilias XVII,350 that the body of Patroklos is covered with a “splendid carpet”. In Odyssey Book VII and X “carpets” are mentioned.

Around 400 BC, the Greek author Xenophon mentions “carpets” in his book “Anabasis”:

"αὖθις δὲ Τιμασίωνι τῷ Δαρδανεῖ προσελθών, ἐπεὶ ἤκουσεν αὐτῷ εἶναι καὶ ἐκπώματα καὶ τάπιδας βαρβαρικάς" [Xen. anab. VII.3.18]

- Next he went to Timasion the Dardanian, for he heard that he had some Persian drinking cups and carpets.

"καὶ Τιμασίων προπίνων ἐδωρήσατο φιάλην τε ἀργυρᾶν καὶ τάπιδα ἀξίαν δέκα μνῶν." [Xen. anab. VII.3.27]

- Timasion also drank his health and presented him with a silver bowl and a carpet worth ten mines.

— Xenophon, Anabasis, 400 BC[15]

Pliny the Elder wrote in (nat. VIII, 48) that carpets (“polymita”) were invented in Alexandria. It is unknown whether these were flatweaves or pile weaves, as no detailed technical information is provided in the texts. Already the earliest known written sources refer to carpets as gifts given to, or required from, high-ranking persons.

Pazyryk: The first surviving pile rug

The oldest known hand knotted rug which is nearly completely preserved, and can, therefore, be fully evaluated in every technical and design aspect is the Pazyryk carpet, dated to the 5th century BC. It was discovered in the late 1940s by the Russian archeologist Sergei Rudenko and his team.[16] The carpet was part of the grave gifts preserved frozen in ice in the Scythian burial mounds of the Pazyryk area in the Altai Mountains of Siberia[17] The provenience of the Pazyryk carpet is under debate, as many carpet weaving countries claim to be its country of origin.[18] The carpet had been dyed with plant and insect dyes from the Mongolian steppes. Wherever it was produced, its fine weaving in symmetric knots and elaborate pictorial design hint at an advanced state of the art of carpet weaving at the time of its production. The design of the carpet already shows the basic arrangement of what was to become the standard oriental carpet design: A field with repeating patterns, framed by a main border in elaborate design, and several secondary borders.

Fragments from Turkestan, Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan

The explorer Mark Aurel Stein found flat-woven kilims dating to at least the fourth or fifth century AD in Turpan, East Turkestan, China, an area which still produces carpets today. Rug fragments were also found in the Lop Nur area, and are woven in symmetrical knots, with 5-7 interwoven wefts after each row of knots, with a striped design, and various colours. They are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.[19]

Carpet fragments dated to the third or fourth century BC were excavated from burial mounds at Bashadar in the Ongudai District, Altai Republic, Russia by S. Rudenko, the discoverer of the Pazyryk carpet. They show a fine weave of about 4650 asymmetrical knots per square decimeter[20]

Other fragments woven in symmetrical as well as asymmetrical knots have been found in Dura-Europos in Syria,[21] and from the At-Tar caves in Iraq,[22] dated to the first centuries AD.

These rare findings demonstrate that all the skills and techniques of dyeing and carpet weaving were already known in western Asia before the first century AD.

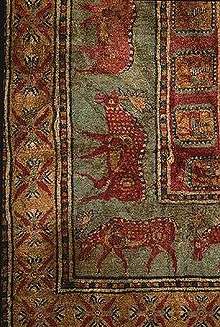

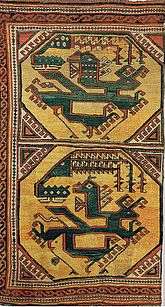

Fragments of pile rugs from findspots in north-eastern Afghanistan, reportedly originating from the province of Samangan, have been carbon-14 dated to a time span from the turn of the second century to the early Sasanian period. Among these fragments, some show depictings of animals, like various stags (sometimes arranged in a procession, recalling the design of the Pazyryk carpet) or a winged mythical creature. Wool is used for warp, weft, and pile, the yarn is crudely spun, and the fragments are woven with the asymmetric knot associated with Persian and far-eastern carpets. Every three to five rows, pieces of unspun wool, strips of cloth and leather are woven in.[23] These fragments are now in the Al-Sabah Collection in the Dar al-Athar al-Islamyya, Kuwait.[24][25]

13th–14th century: The Konya and Fostat fragments; findings from Tibetan monasteries

In the early fourteenth century, Marco Polo wrote about the central Anatolian province of "Turcomania" in his account of his travels:

"The other classes are Greeks and Armenians, who reside in the cities and fortified places, and gain their living by commerce and manufacture. The best and handsomest carpets in the world are wrought here, and also silks of crimson and other rich colours. Amongst its cities are those of Kogni, Kaisariah, and Sevasta."[26]

Coming from Persia, Polo travelled from Sivas to Kayseri. Abu'l-Fida, citing Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi refers to carpet export from Anatolian cities in the lte 13th century: “That's where Turkoman carpets are made, which are exported to all other countries”. He and the Moroccan merchant Ibn Battuta mention Aksaray as a major rug weaving center in the early-to-mid-14th century.

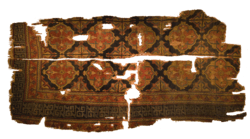

Pile woven Turkish carpets were found in Konya and Beyşehir in Turkey, and Fostat in Egypt, and were dated to the 13th century, which corresponds to the Anatolian Seljuq Period (1243–1302). Eight fragments were found in 1905 by F.R. Martin[27] in the Alâeddin Mosque in Konya, four in the Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir in Konya province by R.M. Riefstahl in 1925.[28] More fragments were found in Fostat, today a suburb of the city of Cairo.[29]

By their original size (Riefstahl reports a carpet up to 6 metres (20 feet) long), the Konya carpets must have been produced in town manufactories, as looms of this size cannot be set up in a nomadic or village home. Where exactly these carpets were woven is unknown. The field patterns of the Konya carpets are mostly geometric, and small in relation to the carpet size. Similar patterns are arranged in diagonal rows: Hexagons with plain, or hooked outlines; squares filled with stars, with interposed kufic-like ornaments; hexagons in diamonds composed of rhomboids, rhomboids filed with stylized flowers and leaves. Their main borders often contain kufic ornaments. The corners are not “resolved”, which means that the border design is cut off, and does not continue around the corners. The colours (blue, red, green, to a lesser extent also white, brown, yellow) are subdued, frequently two shades of the same colour are opposed to each other. Nearly all carpet fragments show different patterns and ornaments.

The Beyşehir carpets are closely related to the Konya carpets in design and colour.[30] In contrast to the "animal carpets" of the following period, depictings of animals are rarely seen in the Seljuq carpet fragments. Rows of horned quadrupeds placed opposite to each other, or birds beside a tree can be recognized on some fragments. A near-complete carpet of this kind is now at the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha. It has survived in a Tibetan monastery and was removed by monks fleeing to Nepal during the Chinese cultural revolution.

The style of the Seljuq carpets finds parallels amongst the architectural decoration of contemporaneous mosques such as those at Divriği, Sivas, and Erzurum, and may be related to Byzantine art.[31] The carpets are today at the Mevlana Museum in Konya, and at the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum in Istanbul.

Current understanding of the origin of pile-woven carpets

Knotted pile woven carpets were likely produced by people who were already familiar with extra-weft wrapping techniques. The different knot types in carpets from locations as distant from each other like the Pazyryk carpet (symmetric), the East Turkestan and Lop Nur (alternate single-weft knots), the At-Tar (symmetric, asymmetric, asymmetric loop knots), and the Fustat fragments (looped-pile, single, asymmetric knots) suggest that the technique as such may have evolved at different places and times.[32]

It is also debated whether pile-knotted carpets were initially woven by nomads who tried to imitate animal pelts as tent-floor coverings,[33] or if they were a product of settled peoples. A number of knives was found in the graves of women of a settled community in southwest Turkestan. The knives are remarkably similar to those used by Turkmen weavers for trimming the pile of a carpet.[34][35] Some ancient motifs on Turkmen carpets closely resemble the ornaments seen on early pottery from the same region.[36] The findings suggest that Turkestan may be among the first places we know of where pile-woven carpets were produced, but this does not mean it was the only place.

In the light of ancient sources and archaeological discoveries, it seems highly likely that the pile-woven carpet developed from one of the extra-weft wrapping weaving techniques, and was first woven by settled people. The technique has probably evolved separately at different places and times. During the migrations of nomadic groups from Central Asia, the technique and designs may have spread throughout the area which was to become the “rug belt” in later times. With the emergence of Islam, the westward migration of nomadic groups began to change Near Eastern history. After this period, knotted-pile carpets became an important form of art under the influence of Islam, and where the nomadic tribes spread, and began to be known as “Oriental” or “Islamic” carpets.[37]

The Pazyryk Carpet. Circa 400 BC. Hermitage Museum

The Pazyryk Carpet. Circa 400 BC. Hermitage Museum Carpet fragment from Eşrefoğlu Mosque, Beysehir, Turkey. Seljuq Period, 13th century.

Carpet fragment from Eşrefoğlu Mosque, Beysehir, Turkey. Seljuq Period, 13th century. Seljuq carpet, 320 by 240 centimetres (126 by 94 inches), from Alâeddin Mosque, Konya, 13th century

Seljuq carpet, 320 by 240 centimetres (126 by 94 inches), from Alâeddin Mosque, Konya, 13th century Animal carpet, Turkey, dated to the 11th–13th century, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

Animal carpet, Turkey, dated to the 11th–13th century, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

Manufacture

An oriental rug is woven by hand on a loom, with warps, wefts, and pile made mainly of natural fibers like wool, cotton, and silk. In representative carpets, metal threads made of gold or silver are woven in. The pile consists of hand-spun or machine-spun strings of yarn, which are knotted into the warp and weft foundation. Usually the pile threads are dyed with various natural or synthetic dyes. Once the weaving has finished, the rug is further processed by fastening its borders, clipping the pile to obtain an even surface, and washing, which may use added chemical solutions to modify the colours.

Materials

Materials used in carpet weaving and the way they are combined vary in different rug weaving areas. Mainly, animal wool from sheep and goats is used, occasionally also from camels. Yak and horse hair have been used in Far Eastern, but rarely in Middle Eastern rugs. Cotton is used for the foundation of the rug, but also in the pile. Silk from silk worms is used for representational rugs.

Wool

In most oriental rugs, the pile is of sheep's wool. Its characteristics and quality vary from each area to the next, depending on the breed of sheep, climatic conditions, pasturage, and the particular customs relating to when and how the wool is shorn and processed.[38] In the Middle East, rug wools come mainly from the fat-tailed and fat-rumped sheep races, which are distinguished, as their names suggest, by the accumulation of fat in the respective parts of their bodies. Different areas of a sheep's fleece yield different qualities of wool, depending on the ratio between the thicker and stiffer sheep hair and the finer fibers of the wool. Usually, sheep are shorn in spring and fall. The spring shear produces wool of finer quality. The lowest grade of wool used in carpet weaving is “skin” wool, which is removed chemically from dead animal skin.[39] Fibers from camels and goats are also used. Goat hair is mainly used for fastening the borders, or selvages, of Baluchi and Turkmen rugs, since it is more resistant to abrasion. Camel wool is occasionally used in Middle Eastern rugs. It is often dyed in black, or used in its natural colour. More often, wool said to be camel's wool turns out to be dyed sheep wool.[40]

Cotton

Cotton forms the foundation of warps and wefts of the majority of modern rugs. Nomads who cannot afford to buy cotton on the market use wool for warps and wefts, which are also traditionally made of wool in areas where cotton was not a local product. Cotton can be spun more tightly than wool, and tolerates more tension, which makes cotton a superior material for the foundation of a rug. Especially larger carpets are more likely to lie flat on the floor, whereas wool tends to shrink unevenly, and carpets with a woolen foundation may buckle when wet.[39] Chemically treated (mercerised) cotton has been used in rugs as a silk substitute since the late nineteenth century.[39]

Silk

Silk is an expensive material, and has been used for representative carpets of the Mamluk, Ottoman, and Safavid courts. Its tensile strength has been used in silk warps, but silk also appears in the carpet pile. Silk pile can be used to highlight special elements of the design in Turkmen rugs, but more expensive carpets from Kashan, Qum, Nain, and Isfahan in Persia, and Istanbul and Hereke in Turkey, have all-silk piles. Silk pile carpets are often exceptionally fine, with a short pile and an elaborate design. Silk pile is less resistant to mechanical stress, thus, all-silk piles are often used as wall hangings, or pillow tapestry. Silk is more often used in rugs of Eastern Turkestan and Northwestern China, but these rugs tend to be more coarsely woven.[39]

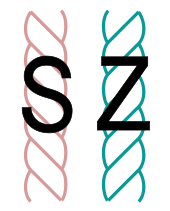

Spinning

The fibers of wool, cotton, and silk are spun either by hand or mechanically by using spinning wheels or industrial spinning machines to produce the yarn. The direction in which the yarn is spun is called twist. Yarns are characterized as S-twist or Z-twist according to the direction of spinning (see diagram).[41] Two or more spun yarns may be twisted together or plied to form a thicker yarn. Generally, handspun single plies are spun with a Z-twist, and plying is done with an S-twist. With the exception of Mamluk carpets, nearly all the rugs produced in the countries of the rug belt use "Z" (anti-clockwise) spun and "S" (clockwise)-plied wool.

Dyeing

The dyeing process involves the preparation of the yarn in order to make it susceptible for the proper dyes by immersion in a mordant. Dyestuffs are then added to the yarn which remains in the dyeing solution for a defined time. The dyed yarn is then left to dry, exposed to air and sunlight. Some colours, especially dark brown, require iron mordants, which can damage or fade the fabric. This often results in faster pile wear in areas dyed in dark brown colours, and may create a relief effect in antique oriental carpets.

Vegetal dyes

Traditional dyes used for oriental rugs are obtained from plants and insects. In 1856, the English chemist William Henry Perkin invented the first aniline dye, mauveine. A variety of other synthetic dyes were invented thereafter. Cheap, readily prepared and easy to use as they were compared to natural dyes, their use is documented in oriental rugs since the mid 1860s. The tradition of natural dyeing was revived in Turkey in the early 1980s, and later on, in Iran.[42] Chemical analyses led to the identification of natural dyes from antique wool samples, and dyeing recipes and processes were experimentally re-created.[43][44]

According to these analyzes, natural dyes used in Turkish carpets include:

- Red from Madder (Rubia tinctorum) roots,

- Yellow from plants, including onion (Allium cepa), several chamomile species (Anthemis, Matricaria chamomilla), and Euphorbia,

- Black: Oak apples, Oak acorns, Tanner's sumach,

- Green by double dyeing with Indigo and yellow dye,

- Orange by double dyeing with madder red and yellow dye,

- Blue: Indigo gained from Indigofera tinctoria.

Some of the dyestuffs like indigo or madder were goods of trade, and thus commonly available. Yellow or brown dyestuffs more substantially vary from region to region. In some instances, the analysis of the dye has provided information about the provenience of a rug.[45] Many plants provide yellow dyes, like Vine weld, or Dyer's weed (Reseda luteola), Yellow larkspur (perhaps identical with the isparek plant), or Dyer's sumach Cotinus coggygria. Grape leaves and pomegranate rinds, as well as other plants, provide different shades of yellow.[46]

Insect reds

Carmine dyes are obtained from resinous secretions of scale insects such as the Cochineal scale Coccus cacti, and certain Porphyrophora species (Armenian and Polish cochineal). Cochineal dye, the so-called "laq" was formerly exported from India, and later on from Mexico and the Canary Islands. Insect dyes were more frequently used in areas where Madder (Rubia tinctorum) was not grown, like west and north-west Persia.[47]

Synthetic dyes

With modern synthetic dyes, nearly every colour and shade can be obtained so that it is nearly impossible to identify, in a finished carpet, whether natural or artificial dyes were used. Modern carpets can be woven with carefully selected synthetic colours, and provide artistic and utilitarian value.[48]

Abrash

The appearance of slight deviations within the same colour is called abrash (from Turkish abraş, literally, “speckled, piebald”). Abrash is seen in traditionally dyed oriental rugs. Its occurrence suggests that a single weaver has likely woven the carpet, who did not have enough time or resources to prepare a sufficient quantity of dyed yarn to complete the rug. Only small batches of wool were dyed from time to time. When one string of wool was used up, the weaver continued with the newly dyed batch. Because the exact hue of colour is rarely met again when a new batch is dyed, the colour of the pile changes when a new row of knots is woven in. As such, the colour variation suggests a village or tribal woven rug, and is appreciated as a sign of quality and authenticity. Abrash can also be introduced on purpose into a pre-planned carpet design.[49]

Madder (Rubia tinctorum) plant

Madder (Rubia tinctorum) plant Indigo, historical dye collection of the Dresden University of Technology, Germany

Indigo, historical dye collection of the Dresden University of Technology, Germany- Kermez (Coccus cacti) lice

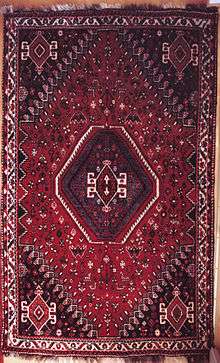

- Section (central medallion) of a South Persian rug, probably Qashqai, late 19th century, showing irregular blue colours (abrash)

Tools

A variety of tools are needed for the construction of a handmade rug. A loom, a horizontal or upright framework, is needed to mount the vertical warps into which the pile nodes are knotted. One or more shoots of horizontal wefts are woven (“shot”) in after each row of knots in order to further stabilize the fabric.

Horizontal looms

Nomads usually use a horizontal loom. In its simplest form, two loom beams are fastened, and kept apart by stakes which are driven into the ground. The tension of the warps is maintained by driving wedges between the loom beams and the stakes. If the nomad journey goes on, the stakes are pulled out, and the unfinished rug is rolled up on the beams. The size of the loom beams is limited by the need to be easily transportable, thus, genuine nomad rugs are often small in size. In Persia, loom beams were mostly made of poplar, because poplar is the only tree which is easily available and straight.[50] The closer the warps are spanned, the more dense the rug can be woven. The width of a rug is always determined by the length of the loom beams. Weaving starts at the lower end of the loom, and proceeds towards the upper end.

Traditionally, horizontal looms were used by the

Vertical looms

The technically more advanced, stationary vertical looms are used in villages and town manufactures. The more advanced types of vertical looms are more comfortable, as they allow for the weavers to retain their position throughout the entire weaving process. In essence, the width of the carpet is limited by the length of the loom beams. While the dimensions of a horizontal loom define the maximum size of the rug which can be woven on it, on a vertical loom longer carpets can be woven, as the completed sections of the rugs can be moved to the back of the loom, or rolled up on a beam, as the weaving proceeds.[50]

There are three general types of vertical looms, all of which can be modified in a number of ways: the fixed village loom, the Tabriz or Bunyan loom, and the roller beam loom.

- The fixed village loom is used mainly in Iran and consists of a fixed upper beam and a moveable lower or cloth beam which slots into two sidepieces. The correct tension of the warps is obtained by driving wedges into the slots. The weavers work on an adjustable plank which is raised as the work progresses.

- The Tabriz loom, named after the city of Tabriz, is used in Northwestern Iran. The warps are continuous and pass around behind the loom. Warp tension is obtained with wedges. The weavers sit on a fixed seat and when a portion of the carpet has been completed, the tension is released, the finished section of the carpet is pulled around the lower beam and upwards on the back of the loom. The Tabriz type of vertical loom allows for weaving of carpets up to double the length of the loom.

- The roller beam loom is used in larger Turkish manufactures, but is also found in Persia and India. It consists of two movable beams to which the warps are attached. Both beams are fitted with ratchets or similar locking devices. Once a section of the carpet is completed, it is wound up on the lower beam. On a roller beam loom, any length of carpet can be produced. In some areas of Turkey several rugs are woven in series on the same warps, and separated from each other by cutting the warps after the weaving is finished.

The vertical loom enables weaving of larger rug formats. The most simple vertical loom, usually used in villages, has fixed beams. The length of the loom determines the length of the rug. As the weaving proceeds, the weavers' benches must be moved upwards, and fixed again at the new working height. Another type of loom is used in manufactures. The wefts are fixed and spanned on the beams, or, in more advanced types of looms, the wefts are spanned on a roller beam, which allows for any length of carpet to be woven, as the finished part of the carpet is rolled up on the roller beam. Thus, the weavers' benches always remain at the same height.

Other tools

Few essential tools are needed in carpet weaving: Knives are used to cut the yarn after the knot is made, a heavy instrument like a comb for beating in the wefts, and a pair of scissors for trimming off the ends of the yarn after each row of knots is finished. From region to region, they vary in size and design, and in some areas are supplemented by other tools. The weavers of Tabriz used a combined blade and hook. The hook projects from the end of the blade, and is used for knotting, instead of knotting with the fingers. Comb-beaters are passed through the warp strings to beat in the wefts. When the rug is completed, the pile is often shorn with special knives to obtain an even surface.[51]

Horizontal nomad loom

Horizontal nomad loom Vertical factory loom seen from the back. Weaver sits down left.

Vertical factory loom seen from the back. Weaver sits down left. Comb beater

Comb beater

Warp, weft, pile

Warps and wefts form the foundation of the carpet, the pile accounts for the design. Warps, wefts and pile may consist of any of these materials:

| warp | weft | pile | often found in |

|---|---|---|---|

| wool | wool | wool | nomad and village rugs |

| cotton | cotton | wool | manufacture rugs |

| silk | silk | silk | manufacture rugs |

| cotton | cotton | silk | manufacture rugs |

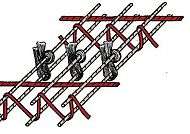

Rugs can be woven with their warp strings held back on different levels, termed sheds. This is done by pulling the wefts of one shed tight, separating the warps on two different levels, which leaves one warp on a lower level. The technical term is “one warp is depressed”. Warps can be depressed slightly, ore more tightly, which will cause a more or less pronounced rippling or “ridging” on the back of the rug. A rug woven with depressed warps is described as “double warped”. Central Iranian city rugs such as Kashan, Isfahan, Qom, and Nain have deeply depressed warps, which make the pile more dense, the rug is heavier than a more loosely woven specimen, and the rug lies more firmly on the floor. Kurdish Bidjar carpets make most pronounced use of warp depression. Often their pile is further compacted by the use of a metal rod which is driven between the warps and hammered down on, which produces a dense and rigid fabric.[52]

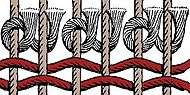

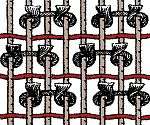

Knots

The pile knots are usually knotted by hand. Most rugs from Anatolia utilize the symmetrical Turkish double knot. With this form of knotting, each end of the pile thread is twisted around two warp threads at regular intervals, so that both ends of the knot come up between two warp strings on one side of the carpet, opposite to the knot. The thread is then pulled downwards and cut with a knife.

Most rugs from other provenances use the asymmetric, or Persian knot. This knot is tied by winding a piece of thread around one warp, and halfway around the next warp, so that both ends of the thread come up at the same side of two adjacent strings of warp on one side of the carpet, opposite to the knot. The pile, i.e., the loose end of the thread, can appear on the left or right side of the warps, thus defining the terms “open to the left” or “open to the right”. Variances in the type of knots are significant, as the type of knot used in a carpet may vary on a regional, or tribal, basis. Whether the knots are open to the left or to the right can be determined by passing one's hands over the pile.[53]

A variant knot is the so-called jufti knot, which is woven around four strings of warp, with each loop of one single knot tied around two warps. Jufti can be knotted symmetrically or asymmetrically, open to the left or right.[52] A serviceable carpet can be made with jufti knots, and jufti knots are sometimes used in large single-colour areas of a rug, for example in the field. However, as carpets woven wholly or partly with the jufti knot need only half the amount of pile yarn than traditionally woven carpets, their pile is less resistant to wear, and these rugs do not last long.[54]

Another variant of knot is known from early Spanish rugs. The Spanish knot or single-warp knot, is tied around one single warp. Some of the rug fragments excavated by A. Stein in Turfan seem to be woven with a single knot. Single knot weavings are also known from Egyptian Coptic pile rugs.[55]

Irregular knots sometimes occur, and include missed warps, knots over three or four warps, single warp knots, or knots sharing one warp, both symmetric and asymmetric. They are frequently found in Turkmen rugs, and contribute to the dense and regular structure of these rugs.

Diagonal, or offset knotting has knots in successive rows occupy alternate pairs of warps. This feature allows for changes from one half knot to the next, and creates diagonal pattern lines at different angles. It is sometimes found in Kurdish or Turkmen rugs, particularly in Yomuds. It is mostly tied symmetrically.[39]

The upright pile of oriental rugs usually inclines in one direction, as knots are always pulled downwards before the string of pile yarn is cut off and work resumes on the next knot, piling row after row of knots on top of each other. When passing one's hand over a carpet, this creates a feeling similar to stroking an animal's fur. This can be used to determine where the weaver has started knotting the pile. Prayer rugs are often woven “upside down”, as becomes apparent when the direction of the pile is assessed. This has both technical reasons (the weaver can focus on the more complicated niche design first), and practical consequences (the pile bends in the direction of the worshipper's prostration).

Knot count

The knot count is expressed in knots per square inch (kpsi) or per square decimeter. Knot count per square decimeter can be converted to square inch by division by 15.5. Knot counts are best performed on the back of the rug. If the warps are not too deeply depressed, the two loops of one knot will remain visible, and will have to be counted as one knot. If one warp is deeply depressed, only one loop of the knot may be visible, which has to be considered when the knots are counted.

Compared to the kpsi counts, additional structural information is obtained when the horizontal and vertical knots are counted separately. In Turkmen carpets, the ratio between horizontal and vertical knots is frequently close to 1:1. Considerable technical skill is required to achieve this knot ratio. Rugs which are woven in this manner are very dense and durable.[56]

Knot counts bear evidence of the fineness of the weaving, and of the amount of labour needed to complete the rug. However, the artistic and utilitarian value of a rug hardly depends on knot counts, but rather on the execution of the design and the colours. For example, Persian Heriz or some Anatolian carpets may have low knot counts as compared to the extremely fine-woven Qom or Nain rugs, but provide artistic designs, and are resistant to wear.

Finishing

Once the weaving is finished, the rug is cut from the loom. Additional work has to be done before the rug is ready for use.

Edges and ends

The edges of a rug need additional protection, as they are exposed to particular mechanical stress. The last warps on each side of the rug are often thicker than the inner warps, or doubled. The edge may consist of only one warp, or of a bundle of warps, and is attached to the rugs by weft shoots looping over it, which is termed an “overcast”. The edges are often further reinforced by encircling it in wool, goat's hair, cotton, or silk in various colours and designs. Edges thus reinforced are called selvedges, or shirazeh from the Persian word.

The remaining ends of the warp threads form the fringes that may be weft-faced, braided, tasseled, or secured in some other manner. Especially Anatolian village and nomadic rugs have flat-woven kilim ends, made by shooting in wefts without pile at the beginning and end of the weaving process. They provide further protection against wear, and sometimes include pile-woven tribal signs or village crests.

Pile

The pile of the carpet is shorn with special knives (or carefully burned down) in order to remove excess pile and obtain an equal surface. In parts of Central Asia, a small sickle-shaped knife with the outside edge sharpened is used for pile shearing. Knives of this shape have been excavated from Bronze Age sites in Turkmenistan (cited in[57]). In some carpets, a relief effect is obtained by clipping the pile unevenly following the contours of the design. This feature is often seen in Chinese and Tibetan rugs.

Washing

Most carpets are washed before they are used or go to the market. The washing may be done with water and soap only, but more often chemicals are added to modify the colours. Various chemical washings were invented in New York, London, and other European centers. The washing often included chlorine bleach or sodium hydrosulfite. Chemical washings not only damage the wool fibers, but change the colours to an extent that some rugs had to be re-painted with different colours after the washing, as is exemplified by the so-called "American Sarouk" carpet.[58]

Turkish (symmetric) knot

Turkish (symmetric) knot Persian (asymmetric) knot, open to the right

Persian (asymmetric) knot, open to the right Variants of the "Jufti" knot woven around four warps

Variants of the "Jufti" knot woven around four warps Diagonal, or offset, knotting

Diagonal, or offset, knotting Weaving with one warp depressed

Weaving with one warp depressed Knitting an asymmetric knot, open to the right

Knitting an asymmetric knot, open to the right Kilim end and fringes

Kilim end and fringes

Design

Oriental rugs are known for their richly varied designs, but common traditional characteristics identify the design of a carpet as “oriental”. With the exception of pile relief obtained by clipping the pile unevenly, rug design originates from a two-dimensional arrangement of knots in various colours. Each knot tied into a rug can be regarded as one "pixel" of a picture, which is composed by the arrangement of knot after knot. The more skilled the weaver or, as in manufactured rugs, the designer, the more elaborate the design.

Rectilinear and curvilinear design

Right image: Serapi carpet, Heriz region, Northwest Persia, circa 1875, with a predominantly rectilinear design

A rug design is described either as rectilinear (or “geometric”), or curvilinear (or “floral”). Curvilinear rugs show floral figures in a realistic manner. The drawing is more fluid, and the weaving is often more complicated. Rectilinear patterns tend to be bolder and more angular. Floral patterns can be woven in rectilinear design, but they tend to be more abstract, or more highly stylized. Rectilinear design is associated with nomadic or village weaving, whereas the intricate curvilinear designs require pre-planning, as is done in factories. Workshop rugs are usually woven according to a plan designed by an artist and handed over to the weaver to execute it on the loom.[59]

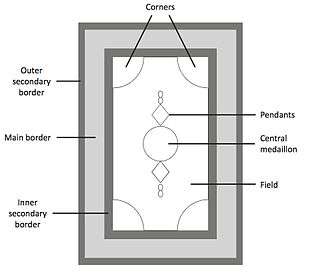

Field design, medallions and borders

_-_Walters_W618binding_-_Top_Exterior_Closed.jpg)

Right image: Basic elements of Oriental carpet design

Rug design can also be described by how the surface of the rug is arranged and organized. One single, basic design may cover the entire field (“all-over design”). When the end of the field is reached, patterns may be cut off intentionally, thus creating the impression that they continue beyond the borders of the rug. This feature is characteristic for Islamic design: In the Islamic tradition, depicting animals or humans is discouraged. Since the codification of the Quran by Uthman Ibn Affan in 651 AD/19 AH and the Umayyad Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan reforms, Islamic art has focused on writing and ornament. The main fields of Islamic rugs are frequently filled with redundant, interwoven ornaments in a manner called "infinite repeat".[60]

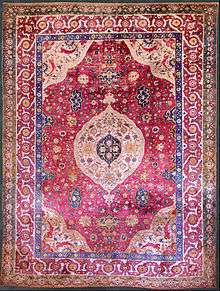

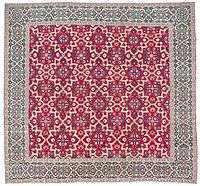

Design elements may also be arranged more elaborately. One typical oriental rug design uses a medallion, a symmetrical pattern occupying the center of the field. Parts of the medallion, or similar, corresponding designs, are repeated at the four corners of the field. The common “Lechek Torūnj” (medallion and corner) design was developed in Persia for book covers and ornamental book illuminations in the fifteenth century. In the sixteenth century, it was integrated into carpet designs. More than one medallion may be used, and these may be arranged at intervals over the field in different sizes and shapes. The field of a rug may also be broken up into different rectangular, square, diamond or lozenge shaped compartments, which in turn can be arranged in rows, or diagonally.[59]

In Persian rugs, the medallion represents the primary pattern, and the infinite repeat of the field appears subordinated, creating an impression of the medallion “floating” on the field. Anatolian rugs often use the infinite repeat as the primary pattern, and integrate the medallion as secondary. Its size is often adapted to fit into the infinite repeat.[61]

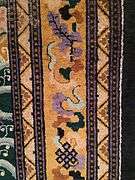

In most Oriental rugs, the field of the rug is surrounded by stripes, or borders. These may number from one up to over ten, but usually there is one wider main border surrounded by minor, or guardian borders. The main border is often filled with complex and elaborate rectilinear or curvilinear designs. The minor border stripes show simpler designs like meandering vines or reciprocal trefoils. The latter are frequently found in Caucasian and some Turkish rugs, and are related to the Chinese “cloud collar” (yun chien) motif.[62] The traditional border arrangement was highly conserved through time, but can also be modified to the effect that the field encroaches on the main border. Seen in Kerman rugs and Turkish rugs from the late eighteenth century "mecidi" period, this feature was likely taken over from French Aubusson or Savonnerie weaving designs. Additional end borders called elem, or skirts, are seen in Turkmen and some Turkish rugs. Their design often differs from the rest of the borders. Elem are used to protect the lower borders of tent door rugs ("ensi"). Chinese and Tibetan rugs sometimes do not have any borders.

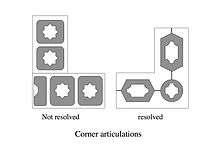

Designing the carpet borders becomes particularly challenging when it comes to the corner articulations. The ornaments have to be woven in a way that the pattern continues without interruption around the corners between horizontal and vertical borders. This requires advance planning either by a skilled weaver who is able to plan the design from start, or by a designer who composes a cartoon before the weaving begins. If the ornaments articulate correctly around the corners, the corners are termed to be “resolved”. In village or nomadic rugs, which are usually woven without a detailed advance plan, the corners of the borders are often not resolved. The weaver has discontinued the pattern at a certain stage, e.g., when the lower horizontal border is finished, and starts anew with the vertical borders. The analysis of the corner resolutions helps distinguishing rural village, or nomadic, from workshop rugs.

Smaller and composite design elements

The field, or sections of it, can also be covered with smaller design elements. The overall impression may be homogeneous, although the design of the elements themselves can be highly complicated. Amongst the repeating figures, the boteh is used throughout the “carpet belt”. Boteh can be depicted in curvilinear or rectilinear style. The most elaborate boteh are found in rugs woven around Kerman. Rugs from Seraband, Hamadan, and Fars sometimes show the boteh in an all-over pattern. Other design elements include ancient motifs like the Tree of life, or floral and geometric elements like, e.g., stars or palmettes.

Single design elements can also be arranged in groups, forming a more complex pattern:[63][64]

- The Herati pattern consists of a lozenge with floral figure at the corners surrounded by lancet-shaped leaves sometimes called “fish”. Herati patterns are used throughout the “carpet belt”; typically, they are found in the fields of Bidjar rugs.

- The Mina Khani pattern is made up of flowers arranged in a rows, interlinked by diamond (often curved) or circular lines. frequently all over the field. The Mina Khani design is often seen on Varamin rugs.

- The Shah Abbasi design is composed of a group of palmettes. Shah Abbasi motifs are frequently seen in Kashan, Isfahan, Mashhad and Nain rugs.

- The Bid Majnūn, or Weeping Willow design is in fact a combination of weeping willow, cypress, poplar and fruit trees in rectilinear form. Its origin was attributed to Kurdish tribes, as the earliest known examples are from the Bidjar area.

- The Harshang or Crab design takes its name from its principal motive, which is a large oval motive suggesting a crab. The pattern is found all over the rug belt, but bear some resemblance to palmettes from the Sefavi period, and the “claws” of the crab may be conventionalized arabesques in rectilinear style.

- The Gol Henai small repeating pattern is named after the Henna plant, which it does not much resemble. The plant looks more like the Garden balsam, and in the Western literature is sometimes compared to the blossom of the Horse chestnut.

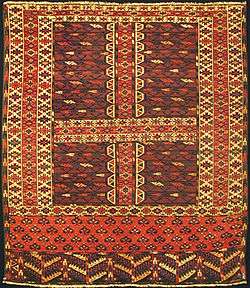

- The Gul design is frequently found in Turkmen rugs. Small round or octagonal medallions are repeated in rows all over the field. Although the Gül medallion itself can be very elaborate and colourful, their arrangement within the monochrome field often generates a stern and somber impression. Güls are often ascribed a heraldic function, as it is possible to identify the tribal provenience of a Turkmen rug by its güls.[65]

Common motifs in Oriental rugs

Boteh motif

Boteh motif- Pictorial carpet with Tree of life, birds, plants, flowers and vase motifs

Karaja carpet with Bid Majnūn, or “weeping willow” design

Karaja carpet with Bid Majnūn, or “weeping willow” design A Carpet from Varamin with the Mina Khani motif

A Carpet from Varamin with the Mina Khani motif- “Cloud band” ornament of Chinese origin in a Persian carpet

Pictorial carpet: Quran verses are woven into a Persian carpet

Pictorial carpet: Quran verses are woven into a Persian carpet- Russian “Bokhara”, with Turkmen Gul design

Special designs

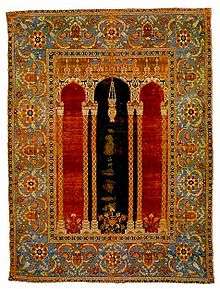

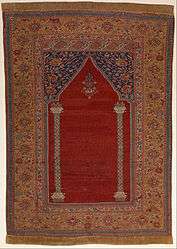

A different type of field design in a specific Islamic design tradition is used in prayer rugs. A prayer rug is characterized by a niche at one end, representing the mihrab, an architectural element in mosques intended to direct the worshippers towards the Qibla. Prayer rugs also show highly symbolic smaller design elements like one or more mosque lamps, a reference to the Verse of Light in the Qur'an, or water jugs, potentially as a reminder towards ritual cleanliness. Sometimes stylized hands or feet appear in the field to indicate where the worshipper should stand, or to represent the praying person's prostration.[66] Other special types include garden, compartment, vase, animal, or pictorial designs

The 15th century "design revolution"

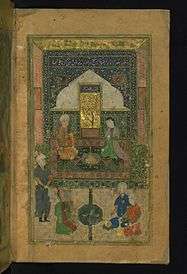

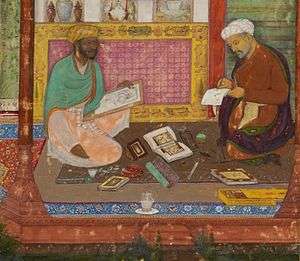

Right image: Court scene, early 16th century miniature, depicting a carpet with "medallion and corners" design Walters Art Museum

During the 15th century, a fundamental change appeared in carpet design. Because no carpets survived from this period, research has focused on Timurid period book illuminations and miniature paintings. Earlier Timurid paintings depict colourful carpets with repeating designs of equal-scale geometric patterns, arranged in checkerboard-like designs, with “kufic” border ornaments derived from Islamic calligraphy. The designs are so similar to period Anatolian carpets, especially the “Holbein carpets” that a common source of the design cannot be excluded: Timurid designs may have survived in both the Persian and Anatolian carpets from the early Safavid, and Ottoman period.[67]

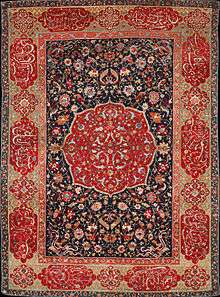

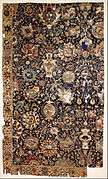

By the late fifteenth century, the design of the carpets depicted in miniatures changed considerably. Large-format medaillons appeared, ornaments began to show elaborate curvilinear designs. Large spirals and tendrils, floral ornaments, depictions of flowers and animals, were often mirrored along the long or short axis of the carpet to obtain harmony and rhythm. The earlier “kufic” border design was replaced by tendrils and arabesques. The resulting change in carpet design was what Kurt Erdmann termed the “carpet design revolution”.[68]

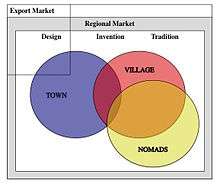

Intra- and intercultural contexts

Four "social layers" of carpet production can be distinguished: Rugs were woven simultaneously by and for nomads, rural villages, towns, and the royal court. Rural village, and nomad carpet designs represent independent artistic traditions.[69] Elaborate rug designs from court and town were integrated into village and nomadic design traditions by means of a process termed stylization.[2] When rugs are woven for the market, the weavers adapt their production in order to meet the customers' demands, and to maximize their profit. As is the case with Oriental rugs, adaptation to the export market has brought forth both devastating effects on the culture of rug weaving, but has also led to a revival of old traditions in more recent years.

Representative ("court") carpets

Representative "court" rugs were woven by special workshops, often founded and supervised by the sovereign, with the intention to represent power and status:[70] The East Roman (Byzantine) and the Persian Sasanian Empires have coexisted for more than 400 years. Artistically, both empires have developed similar styles and decorative vocabularies, as exemplified by mosaics and architecture of Roman Antioch.[71] An Anatolian carpet pattern depicted on Jan van Eyck's “Paele Madonna” painting was traced back to late Roman origins and related to early Islamic floor mosaics found in the Umayyad palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar.[72] Rugs were produced in the court manufactures as special commissions or gifts (some carpets included inwoven European coats of arms). Their elaborate design required a division of work between an artist who created a design plan (termed “cartoon”) on paper, and a weaver who was given the plan for execution on the loom. Thus, artist and weaver were separated.[23] Their appearance in Persian book illuminations and miniatures as well as in European paintings provides material for their dating by using the “terminus ante quem” approach.

Town, village, nomadic rugs

High-status examples like Safavid or Ottoman court carpets are not the only foundation of the historical and social framework. The reality of carpet production does not reflect this selection: Carpets were simultaneously produced by and for the three different social levels. Patterns and ornaments from court manufactory rugs have been reproduced by smaller (town or village) workshops. This process is well documented for Ottoman prayer rugs.[2] As prototypical court designs were passed on to smaller workshops, and from one generation to the next, the design underwent a process termed stylization, comprising series of small, incremental changes either in the overall design, or in details of smaller patterns and ornaments, over time. As a result, the prototype may be modified to an extent as to barely being recognizable. A mihrab column may change into a detached row of ornaments, a Chinese dragon may undergo stylization until it becomes unrecognizable in a Caucasian dragon carpet.[2]

Stylization in Turkish prayer rug design

Ottoman court prayer rug, Bursa, late 16th century (James Ballard collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Ottoman court prayer rug, Bursa, late 16th century (James Ballard collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art) Turkish prayer rug

Turkish prayer rug- Bergama prayer rug, late 19th century

Pile rugs and flat weaves were essential items in all rural households and nomadic tents. They were part of a tradition that was at times influenced, but essentially distinct from the invented designs of the workshop production. Frequently, mosques had acquired rural carpets as charitable gifts, which provided material for studies.[73] Rural carpets rarely include cotton for warps and wefts, and almost never silk, as these materials had to be purchased on the market.

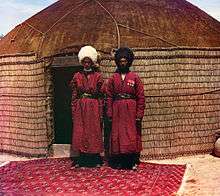

With the end of the traditional nomadic lifestyle in large parts of the rug belt area, and the consequent loss of specific traditions, it has become difficult to identify a genuine “nomadic rug”. Tribes known for their nomadic lifestyle like the Yürük in Anatolia, or the Kurds and Qashqai in contemporary Turkey and Southwestern Iran have voluntarily or by force acquired sedentary lifestyles. Migration of peoples and tribes, in peace or warfare, has frequently happened throughout the history of Turkic peoples, as well as Persian and Caucasian tribes. Some designs may have been preserved, which can be identified as specifically nomadic or tribal.[74][75][76][77][78] “Nomadic” rugs can be identified by their material, construction, and colours. Specific ornaments can be traced back in history to ancient motifs.[78]

Criteria for nomadic production include:[79]

- Unusual materials like warps made of goat's hair, or camel wool in the pile;

- high quality wool with long pile (Anatolian and Turkmen nomads);

- small format fitting for a horizontal loom;

- irregular format due to frequent re-assembly of the loom, resulting in irregular tension of the warps;

- pronounced abrash (irregularities within the same colour due to dyeing of yarn in small batches);

- inclusion of flat weaves at the ends.

Within the genre of carpet weaving, the most authentic village and nomadic products were those woven to serve the needs of the community, which were not intended for export or trade other than local. This includes specialized bags and bolster covers (yastik) in Anatolia, which show designs adapted from the earliest weaving traditions.[80] In Turkmen tents, large wide bags (chuval) were used to keep clothings and household articles. Smaller (torba) and midsize (mafrash) and a variety of special bags to keep bread or salt were woven. They are usually made of two sides, one or both of them pile or flat-woven, and then sewn together. Long tent bands woven in mixed pile and flat weave adorned the tents, and carpets known as ensi covered the entrance of the tent, while the door was decorated with a pile-woven door surround. Turkmen, and also tribes like the Bakhtiari nomads of western Iran, or the Qashqai people wove animal trappings like saddle covers, or special decorations for weddings like asmalyk, pentagonally shaped camel coverings used for wedding decorations. Tribal signs like the Turkmen Gül can support the assessment of provenience.[2]

Symbolism and the origin of patterns

May H. Beattie[81] (1908–1997), a distinguished scholar in the field of carpet studies, wrote in 1976:[82]

The symbolism of Oriental rug designs has recently been made the subject of a number of articles. Many of the ideas put forward are of great interest, but to attempt to discuss such a subject without a profound knowledge of the philosophies of the East would be unwise, and could easily provide unreliable food for unbridled imaginations. One may believe implicitly in certain things, but especially if they have an ancient religious basis, it may not always be possible to prove them. Such ideas merit attention.

— May H. Beattie, Carpets of central Persia, 1976, p. 19

Oriental rugs from various proveniences often share common motifs. Various attempts have been made to determine the potential origin of these ornaments. Woven motifs of folk art undergo changes through processes depending on human creativity, trial and error, and unpredictable mistakes,[83] but also through the more active process of stylization. The latter process is well documented, as the integration into the work of rural village and nomad weavers of patterns designed in town manufactures can be followed on carpets which still exist. In the more archaic motifs, the process of pattern migration and evolution cannot be documented, because the material evidence does not exist any more. This has led to various speculations about the origins and “meanings” of patterns, often resulting in unsubstantiated claims.

Prehistoric symbolism

In 1967, the British archaeologist James Mellaart claimed to have found the oldest records of flat woven kilims on wall paintings he discovered in the Çatalhöyük excavations, dated to circa 7000 BC.[84] The drawings Mellaart claimed to have made before the wall paintings disappeared after their exposure showed clear similarities to nineteenth century designs of Turkish flatweaves. He interpreted the forms, which evoked a female figure, as evidence of a Mother Goddess cult in Çatalhöyük. A well-known pattern in Anatolian kilims, sometimes referred to as Elibelinde (lit.: “hands on hips”), was therefore determined to depict the Mother Goddess herself. This theory had to be abandoned after Mellaarts claims were denounced as fraudulent,[85] and his claims refuted by other archaeologists. The elibelinde motif lost its divine meaning and prehistoric origin. It is today understood as a design of stylized carnation flowers, and its development can be traced back in a detailed and unbroken line to Ottoman court carpets of the sixteenth century.[2]

Variations of the Elibelinde motif

Apotropaic symbols

Symbols of protection against evil are frequently found on Ottoman and later Anatolian carpets. The Turkish name for these symbols is nazarlık (lit.: "[protection from] the evil eye"). Apotropaic symbols include the Cintamani motif, often depicted on white ground Selendi carpets, which consists of three balls and a pair of wavy stripes. It serves the same purpose as protective inscriptions like "May God protect", which are seen woven into rugs. Another protective symbol often woven into carpets is the triangular talisman pendant, or "muska". This symbol is found in Anatolian, Persian, Caucasian and Central Asian carpets.[2]

Tribal symbols

Some carpets include symbols which serve as a tribal crest and sometimes allow for the identification of the weaver's tribe. This is especially true for Turkmen pile woven textiles, which depict a variety of different medallion-like polygonal patterns called Gul, arranged in rows all over the field. While the origin of the pattern can be traced back to Buddhist depictions of the lotus blossom,[62] it remains questionable if the weaver of such a tribal symbol was aware of its origins.

"Kufic" borders

Early Anatolian carpets often show a geometric border design with two arrowhead-like extensions in a sequence of tall-short-tall. By its similarity to the kufic letters of alif and lām, borders with this ornament are called "kufic" borders. The letters are thought to represent the word “Allah”. Another theory relates the tall-short-tall ornament to split-palmette motifs. The "alif-lām" motif is already seen on early Anatolian carpets from the Eşrefoğlu Mosque in Beyşehir.[86]

Arabic letter "alif:"

| Position in word: | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ا | ـا | ـا | ا |

Arabic letter "lām:"

| Position in word: | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ل | ـل | ـلـ | لـ |

Symbolism of the prayer rug

The symbolism of the Islamic Prayer rug is more easily understandable. A prayer rug is characterized by a niche at one end, representing the mihrab in every mosque, a directional point to direct the worshipper towards Mecca. Often one or more mosque lamps hang from the point of the arch, a reference to the Verse of Light in the Qur'an. Sometimes a comb and pitcher are depicted, which is a reminder for Muslims to wash their hands and for men to comb their hair before performing prayer. Stylized hands are woven in the rug pile, indicating where the hands should be placed when performing prayer, often also interpreted as the Hamsa, or “Hand of Fatima”, a protective amulet against the evil eye.

Works on symbolism, and books which include more detailed information on the origin of ornaments and patterns in Oriental carpets include:

- E. Moshkova: Carpets of the people of Central Asia of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Tucson, 1996. Russian edition, 1970[87]

- S. Camman: The Symbolism of the cloud collar motif.[88]

- J. Thompson: Essay on "Centralized Designs"[62]

- J. Opie: Tribal Rugs of Southern Persia, Portland, Oregon, 1981[77]

- J. Opie: Tribal rugs, 1992[78]

- W. Denny: How to read Islamic carpets,[2] section "Reading carpet symbolism", p. 109–127

Cultural effects of commercialization

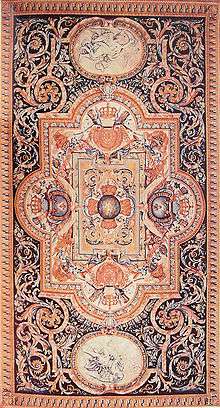

Since the beginning of the Oriental rug trade in the High Middle Ages, Western market demand has influenced the rug manufacturers producing for export, who had to adapt their production in order to accommodate Western market demands. The commercial success of oriental rugs, and the mercantilistic thinking which arose during the sixteenth century, led European sovereigns to initiate and promote carpet manufactories in their European home countries. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Western companies set up weaving facilities in the rug-producing countries, and commissioned designs specifically invented according to Western taste.

Rugs exist which are known to be woven in European manufactories as early as the mid sixteenth century, imitating the technique and, to some extent, the designs of Oriental rugs. In Sweden, flat and pile woven rugs (called “rya”, or “rollakan”) became part of the folk art, and are still produced today, mostly in modern designs. In other countries, like Poland or Germany, the art of carpet weaving did not last long. In the United Kingdom, Axminster carpets were produced since the mid-eighteenth century. In France, the Savonnerie manufactory began weaving pile carpets by the mid-seventeenth centuries, but turned to European-style designs later on, which in turn influenced the Anatolian rug production during the “mecidi”, or “Turkish baroque” period. The Manchester-based company Ziegler & Co. maintained workshops in Tabriz and Sultanabad (now Arak) and supplied retailers such as Liberty & Company and Harvey Nichols. Their designs were modifications of the traditional Persian. A. C. Edwards was the manager of the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers' operations[89] in Persia from 1908 to 1924, and wrote one of the classical textbooks about the Persian carpet.[58]

Polish carpet, mid 18th century

Polish carpet, mid 18th century- Detail of a woven carpet fragment, German, ca. 1540, wool, symmetric knots, 850-1500 kpsdm

- Closeup detail of a woven carpet, Germany, ca. 1540

French Savonnerie carpet (after Charles Le Brun) for the Grand Gallery of the Louvre

French Savonnerie carpet (after Charles Le Brun) for the Grand Gallery of the Louvre Savonnerie carpet detail

Savonnerie carpet detail

In the late nineteenth century, the Western invention of synthetic dyes had a devastating effect on the traditional way of carpet production.[90][91] During the early twentieth century, carpets were woven in the cities of Saruk and Arak, Iran and the surrounding villages mainly for export to the U.S. While the sturdy construction of their pile appealed to U.S. American customers, their designs and colours did not fit in with the demands. The traditional design of the Saruk rug was modified by the weavers towards an allover design of detached floral motives, the carpets were then chemically washed to remove the unwanted colours, and the pile was painted over again with more desirable colours.[92]

In its home countries, the ancient art and craft of carpet weaving has been revived. Since the early 1980s, initiatives were ongoing like the DOBAG project in Turkey, in Iran,[42] and by various social projects in Afghanistan and amongst Tibetan refugees in Northern India. Naturally dyed, traditionally woven rugs are available on the Western market again.[93] With the end of the U.S. embargo on Iranian goods, also Persian carpets (including antique carpets sold at auctions) may become more easily available to U.S. customers again.

Forgery

Oriental rugs have always attracted collectors' interest, and sold at high prizes.[94] This has also been an incentive for fraudulent behaviour.[30] Techniques used traditionally in rug restoration, like replacing knots, or re-weaving parts of a rug, can also be used to modify a rug so as to appear older or more valuable than it actually is. Old flatweaves can be unravelled to obtain longer threads of yarn which can then be re-knitted into rugs. These forgeries are able to overcome chromatographic dye analysis and radiocarbon dating, since they make use of period material.[95] The Romanian artisan Teodor Tuduc has become famous for his fake oriental rugs, and the stories which he delivered in order to gain credibility. The quality of his forgeries was such that some of his rugs found their way into museum collections, and “Tuduc rugs” have themselves become collectable.[96]

Rugs by regions

Oriental rugs can be classified by their region of origin, each of which represents different strands of tradition: Persian rugs, Pakistani rugs, Arabian rugs, Anatolian rugs, Kurdish rugs, Caucasian rugs, Central Asian rugs, Turkestanian (Turkmen, Turkoman) rugs, Chinese rugs, Tibetan rugs and Indian rugs.

Persian (Iranian) rugs

The Persian carpet or Persian rug is an essential and distinguished part of Persian culture and art, and dates back to ancient Persia. Persian carpets are classified by the social setting in which they were woven (nomads, villages, town and court manufactories), by ethnic groups (e.g. Kurds, nomadic tribes such as the Qashqai or Bakhtiari; Afshari, Azerbaijani, Turkmens) and others, or by the town or province where carpets are woven, such as Heriz, Hamadan, Senneh, Bijar, Arak (Sultanabad), Mashhad, Isfahan, Kashan, Qom, Nain, and others. A technical classification for Persian carpets is based on material used for warps, wefts, and pile, spinning and plying of the yarn, dyeing, weaving technique, and aspects of finishing including the ways how the sides (selvedges) and ends are reinforced against wear.

Anatolian (Turkish) rugs

Turkish carpets are produced mainly in Anatolia, including neighbouring areas. Carpet weaving is a traditional art in Anatolia, dating back to pre-Islamic times, and integrates different cultural traditions reflecting the history of Turkic peoples. Turkish carpets form an essential part of the Turkish culture.

Amongst Oriental rugs, the Turkish carpet is distinguished by particular characteristics of dyes and colours, designs, textures and techniques. Usually made of wool and cotton, Turkish carpets are tied with the Turkish, or symmetrical knot. The earliest known examples for Turkish carpets date from the thirteenth century. Distinct types of carpets have been woven ever since in workshops, in more provincial weaving facilities, as well as in villages, tribal settlements, or by nomads. Carpets were simultaneously produced for these different levels of society, with varying materials like sheep wool, cotton, and silk. Pile woven as well as flat woven carpets (Kilim, Soumak, Cicim, Zili) have attracted collectors' and scientists' interest. Following a decline which began in the second half of the nineteenth century, initiatives like the DOBAG Carpet Initiative in 1982, or the Turkish Cultural Foundation in 2000, started to revive the traditional art of Turkish carpet weaving by using hand-spun, naturally-dyed wool and traditional designs.[97]

The Turkish carpet is distinct from carpets of other provenience in that it makes more pronounced use of primary colours. Western Anatolian carpets prefer red and blue colours, whereas Central Anatolian use more red and yellow, with sharp contrasts set in white. With the exceptions of representative court and town manufacture designs, Turkish carpets make more pronounced use of bold geometric, and highly stylized floral patterns, generally in rectilinear design.[98]

Egyptian Mamluk rugs

Under the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt, a distinctive carpet was produced in Egypt. Called "Damascene" carpets by previous centuries, there is no doubt now that the center of production was Cairo.[99] In contrast to nearly all other oriental rugs, Mamluk carpets used “S” (clockwise) spun and “Z” (anti-clockwise)-plied wool. Their palette of colours and shades is limited to bright red, pale blue, and light green, blue and yellow are rarely found. The field design is characterized by polygonal medallions and stars and stylized floral patterns, arranged in a linear way along their central axis, or centralized. The borders contain rosettes, often alternating with cartouches. As Edmund de Unger pointed out, the design is similar to other products of Mamluk manufacture, like wood- and metal work, and book bindings, illuminated books and floor mosaics.[100] Mamluk carpets were made for the court, and for export, Venice being the most important market place for Mamluk rugs in Europe.[99]

After the 1517 Ottoman conquest of the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt, two different cultures merged, as is seen on Mamluk carpets woven after this date. The Cairene weavers adopted an Ottoman Turkish design.[101] The production of these carpets continued in Egypt, and probably also in Anatolia, into the early 17th century.[102]

Caucasian rugs

The Caucasian provinces of Karabagh, Moghan, Shirvan, Daghestan and Georgia formed the northern territories of the Safavid Empire. In the Treaty of Constantinople (1724) and the Treaty of Gulistan, 1813, the provinces were finally ceded to Russia. Russian rule was further extended to Baku, Genje, the Derbent khanate, and the region of Talish. In the 19th century the main weaving zone of the Caucasus was in the eastern Transcaucasus south of the mountains that bisect the region diagonally, in a region which today comprises Azerbaijan, Armenia, and parts of Georgia. In 1990, Richard E. Wright claimed that ethnicities other than the Turk Azeri population "also practiced weaving, some of them in other parts of the Caucasus, but they were of lesser importance."[103] Russian population surveys from 1886 and 1897[104] have shown that the ethnic distribution of the population is extremely complex in the southern Caucasus. With regard to antique carpets and rugs, the weavers' identity or ethnicity remains unknown. Eiland & Eiland stated in 1998 that "it should not be taken for granted that the majority population in a particular area was also responsible for the weaving."[105] Thus, a variety of theories about the ethnic origin of carpet patterns, and a variety of classifications have been put forward, sometimes attributing one and the same carpet to different ethnic groups. The debate is still ongoing, and remains unresolved.

In 1728 the Polish Jesuit Thaddaeus Krusinski wrote that at the beginning of the seventeenth century Shah Abbas I of Persia had established carpet manufactories in Shirvan and Karabagh.[106] The Caucasian carpet weavers adopted Safavid field divisions and floral motifs, but changed their style according to their ancient traditions. Characteristic motifs include stylized Chinese dragons in the so-called “Dragon carpets”, combat scenes of tigers and stags, or floral motifs. The style is highly abstract to an extent that the animal forms become unrecognizable, unless compared to earlier Safavid animals and 16th century "vase style" carpets depicting the same motifs.[107] Among the most popular groups of Caucasian rugs are the “Star Kazak”[108][109] and “Shield Kazak” carpets.[110]

A precise classification of Caucasian rugs is particularly difficult, even compared to other types of oriental rugs. Virtually no information is available from before the end of the nineteenth century, when Caucasian rugs began to be exported in larger numbers. In the Soviet socialistic economy, carpet production was organized in industrial lines in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Daghestan and Georgia, which used standardized designs based on traditional motifs, provided on scalepaper cartoons by specialized artists.[39] In 1927, the Azerbaijani Carpet Association was founded as a division of the Azerbaijani Art Association. At their factories, wool and cotton were processed and handed out to the weavers, who had to join the association.[111] The Azerbaijani scholar Latif Karimov wrote[111] that between 1961 and 1963, a technical college devoted to teaching carpet weaving was built, in 1961, the National Azerbaijan M.A. Aliev Institute of Art opened a department headed by Karimov, which specialized on the training of carpet designers.

Detailed ethnographic information is available from the works of ethnologists like Vsevolod Miller and Soviet Russian surveys conducted by the Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography (cited in[112]) However, during the long period of industrial production, the connection between specific designs and their ethnic and geographic origins may have been lost. Research was published mainly in Russian language, and still is not fully available to non-Russian speaking scientists.[111] From a Western perspective, when scientific interest started to develop in Oriental rugs by the end of the nineteenth century, the Caucasian regions, being part of the Soviet Union, closed up to the West. Thus, Western information about carpet weaving in the Caucasian countries was not as detailed as from other regions of the "carpet belt".[108]

Different classifications have been proposed, however, many trade names and labels have been kept merely as terms of convenience, and future research may allow for more precise classification.[113][114]

More recently, archival research from earlier Russian and Soviet sources has been included,[115] and cooperations were initiated between Western and Azerbaijani experts.[111] They propose the study of flatweaves as the major indigenous folk art of the Caucasus, and worked on more specific and detailed classifications.

Classification by Zollinger, Karimov, and Azadi

Zollinger, Kerimov and Azadi propose a classification for Caucasian rugs woven from the late 19th century onwards.[111] Essentially, they focus on six provenances:

- Kuba relates to a district and its town, located between Baku and Derbent, the Samur river constituting its northern, the southern crest of the Caucasus its southern border.Kuba borders the Baku district in the southeast, and the Caspian Sea n the east. Kuba rugs are classified as town rugs, with dense ornamentation, high knot density, and short pile. Warps are made of wool, not dyed and dark ivory. Wefts are of wool, wool and cotton, or cotton. One of two wefts is often deeply depressed. Knots are symmetrical. Plain-woven Soumakh ends of dark wool or light blue cotton are frequent, white cotton soumakhs are rare. The fringes are braided, pleated, or artistically knotted. The selvedges are mainly round (in that case, in dark blue wool) or 0.3–1 cm wide and made of light blue wool, reinforced over two ribs by figure-of-eight wrapping with supplemental threads. The colours are dark and the rugs look hardly polychrome despite the fact that they use 10–12 different colours, because their ornaments are small and arranged densely on the rug. The majority of Kuba rugs have a dark blue background. Red or dark red rarely occur, sometimes ivory, rarely yellow and hardly any green.

- Shirvan is the name of the town and province, located on the western coast of the Caspian Sea, east of the Kura river, between the southern part of the river and the city of Derbent in the north. Kerimov distinguished six districts, which weave different types of rugs. Some Shirvan rugs come with a high knot density and short pile. More coarsely woven carpets have a higher pile. Symmetrical knots are used, woven with alternate warps depressed. The weft is generally of wool, in dark ivory to brown. The ends are flat-woven, light cotton or wool sumakh. The fringes are sometimes artistically knotted. The selvedges are either round, or 0.5–1 cm wide, in white cotton, with 2–3 ribs in figure-of-eight wrapping with supplemental threads. White cotton selvedges are the most common in Shirvan rugs. Shirvan rugs may have town, or village designs, but less densely ornamented as compared to Kuba rugs, and the drawing is more sparse. Compared to Kuba rugs, Shirvan rugs are lighter, and more colourful, with a dark blue background. The borders often have a light background which is more sparsely ornamented compared to the central field. Light ivory, red or yellow rarely occur. Ivory is mainly used for prayer rugs.

- Gyanya (Genje) is a large city, located ca. 360 kilometres (220 miles) west of Baku.In contrast to the more urban design of Kuba and Shirvan, rugs from other provenances have longer piles. On average, the pile of Gyanya rugs is 6–15 mm high. The warp is generally darker, mainly wool, not dyed dark or light brown. Camel hair is said to be used for warps as well. Wefts are commonly dyed light to dark brownish red. Three wefts are often shot in after each row of knots, but warps are not depressed. The upper end is often 2–6 cm (0.79–2.36 in) long brownish-red tapestry weave, turned over and sewn on. The lower end is frequently red woolen tapestry weave, with the warp loops uncut. Selvedges are rarely round, but flat and wide, mainly dark brownish red, and consist of three ribs with figure-of-eight wrapping with supplemental threads. The second most common shape is similar, but includes only two ribs. Gyanya rugs are more generously and sparsely ornamented, as compared to Kuba and Shirvan weavings. Large square, rectangular, hexagonal and octagonal patterns are set within more open space. Medallions (gul) are often hooked. The colour palette is more restricted than in Kuba and Shirvan rugs, but distributed over larger areas, so that the overall impression is more colourful.