Criticism of the Quran

The Quran has been criticized both in the sense of being studied as a text for historical, literary, sociological and theological analysis[1] but also in the sense of being found fault with by those who argue it is not divine, not perfect and/or not particularly morally elevated.

| Quran |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

| This article is of a series on |

| Criticism of religion |

|---|

|

By religion

|

|

By religious figure

|

|

By text |

In the 1730s the Christian translator, George Sale, published his "Peculiarities of the Quran", the third chapter in his Preliminary Discourse to his "Alkoran of Mohammed". In historical criticism, scholars (such as John Wansbrough, Joseph Schacht, Patricia Crone, Michael Cook) seek to investigate and verify the origin, text, composition, history of the Quran,[2] examining questions, puzzles, difficult text, etc. as they would non-sacred ancient texts. Ibn Warraq found internal inconsistency and scientific errors in the book, and faults with its clarity, authenticity, and ethical message.[3] The most common criticisms concern various pre-existing sources that Quran relies upon, internal consistency, clarity and moral teachings.

Historical authenticity

Traditional view

According to Islamic tradition, the Quran is the literal word of God as recited to the Islamic prophet Muhammad through the archangel Gabriel. Muhammad, according to tradition, recited perfectly what the archangel Gabriel revealed to him for his companions to write down and memorize. Muslims believe that the wording of the Quranic text available today corresponds exactly to that revealed to Muhammad in the years 610–632.[4]

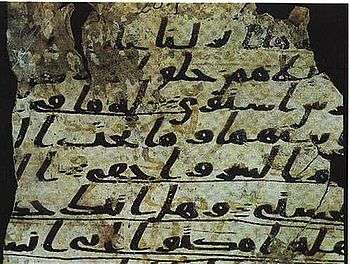

The early Arabic script transcribed 28 consonants, of which only 6 can be readily distinguished, the remaining 22 having formal similarities which means that what specific consonant is intended can only be determined by context. It was only with the introduction of Arabic diacritics some centuries later, that an authorized vocalization of the text, and how it was to be read, was established and became canonical.[5]

Prior to this period, there is evidence that the unpointed text could be read in different ways, with different meanings. Tabarī prefaces his early commentary on the Quran illustrating that the precise way to read the verses of the sacred text was not fixed even in the day of the Prophet. Two men disputing a verse in the text asked Ubay ibn Ka'b to mediate, and he disagreed with them, coming up with a third reading. To resolve the question, the three went to Muhammad. He asked first one-man to read out the verse, and announced it was correct. He made the same response when the second alternative reading was delivered. He then asked Ubay to provide his own recital, and, on hearing the third version, Muhammad also pronounced it ‘Correct!’. Noting Ubay's perplexity and inner thoughts, Muhammad then told him, ‘Pray to God for protection from the accursed Satan.’[6]

Similarities with Jewish and Christian narratives

The Quran contains references to more than 50 people in the Bible, which predates it by several centuries. Stories related in the Quran usually focus more on the spiritual significance of events than details.[7] The stories are generally comparable, but there are differences. One of the most famous differences is the Islamic view of Jesus' crucifixion. The Quran maintains that Jesus was not actually crucified and did not die on the cross. The general Islamic view supporting the denial of crucifixion was probably influenced by Manichaenism (Docetism), which holds that someone else was crucified instead of Jesus, while concluding that Jesus will return during the end-times.[8]

That they said (in boast), "We killed Christ Jesus the son of Mary, the Messenger of Allah";- but they killed him not, nor crucified him, but so it was made to appear to them, and those who differ therein are full of doubts, with no (certain) knowledge, but only conjecture to follow, for of a surety they killed him not:-

Nay, Allah raised him up unto Himself; and Allah is Exalted in Power, Wise;-

Despite these views, many scholars have maintained that the Crucifixion of Jesus is a fact of history and not disputed.[10]

Earliest witness testimony

The last recensions to make an official and uniform Quran in a single dialect were effected under Caliph Uthman (644–656) starting some twelve years after the Prophet's death and finishing twenty-four years after the effort began, with all other existing personal and individual copies and dialects of the Quran being burned:

When they had copied the sheets, Uthman sent a copy to each of the main centers of the empire with the command that all other Qur'an materials, whether in single sheet form, or in whole volumes, were to be burned.[11]

It is traditionally believed the earliest writings had the advantage of being checked by people who already knew the text by heart, for they had learned it at the time of the revelation itself and had subsequently recited it constantly. Since the official compilation was completed two decades after Muhammad's death, the Uthman text has been scrupulously preserved. Bucaille believed that this did not give rise to any problems of this Quran's authenticity.[12]

Muir's The Life of Mahomet explains the outcome of these oral traditions when researching Al-Bukhari:

Reliance upon oral traditions, at a time when they were transmitted by memory alone, and every day produced new divisions among the professors of Islam, opened up a wide field for fabrication and distortion. There was nothing easier, when required to defend any religious or political system, than to appeal to an oral tradition of the Prophet. The nature of these so-called traditions, and the manner in which the name of Muhammad was abused to support all possible lies and absurdities, may be gathered most clearly from the fact that Al-Bukhari who travelled from land to land to gather from the learned the traditions they had received, came to conclusion, after many years sifting, that out of 600,000 traditions, ascertained by him to be then current, only 4000 were authentic![13]

Regarding who was the first to collect the narrations, and whether or not it was compiled into a single book by the time of Muhammad's death is contradicted by witnesses living when Muhammad lived, several historical narratives appear:

Zaid b. Thabit said:

The Prophet died and the Qur'an had not been assembled into a single place.[14]

It is reported... from Ali who said:

May the mercy of Allah be upon Abu Bakr, the foremost of men to be rewarded with the collection of the manuscripts, for he was the first to collect (the text) between (two) covers.[15]

It is reported... from Ibn Buraidah who said:

The first of those to collect the Qur'an into a mushaf (codex) was Salim, the freed slave of Abu Hudhaifah.[16]

Extant copies prior to Uthman version

The Sana'a manuscript contains older portions of the Quran showing variances different from the Uthman copy. The parchment upon which the lower codex of the Sana'a manuscript is written has been radiocarbon dated with 99% accuracy to before 671 CE, with a 95.5% probability of being older than 661 CE and 75% probability from before 646 CE.[17] Tests by the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit indicated with a probability of more than 94 percent that the parchment dated from 568 to 645.[18] The Sana'a palimpsest is one of the most important manuscripts of the collection in the world. This palimpsest has two layers of text, both of which are Quranic and written in the Hijazi script. While the upper text is almost identical with the modern Qurans in use (with the exception of spelling variants), the lower text contains significant diversions from the standard text. For example, in sura 2, verse 87, the lower text has wa-qaffaynā 'alā āthārihi whereas the standard text has wa-qaffaynā min ba'dihi. The Sana'a manuscript has exactly the same verses and the same order of verses as the standard Qur'an.[19] The order of the suras in the Sana'a codex is different from the order in the standard Quran.[20] Such variants are similar to the ones reported for the Quran codices of Companions such as Ibn Masud and Ubay ibn Ka'b. However, variants occur much more frequently in the Sana'a codex, which contains "by a rough estimate perhaps twenty-five times as many [as Ibn Mas'ud's reported variants]".[21]

In 2015, the University of Birmingham disclosed that scientific tests may show a Quran manuscript in its collection as one of the oldest known and believe it was written close to the time of Muhammad. The findings in 2015 of the Birmingham Manuscripts lead Joseph E. B. Lumbard, Assistant Professor of Classical Islam, Brandeis University, to comment:[22]

These recent empirical findings are of fundamental importance. They establish that as regards the broad outlines of the history of the compilation and codification of the Quranic text, the classical Islamic sources are far more reliable than had hitherto been assumed. Such findings thus render the vast majority of Western revisionist theories regarding the historical origins of the Quran untenable.

— Joseph E. B. Lumbard

Dr Saud al-Sarhan, Director of Center for Research and Islamic Studies in Riyadh, questions whether the parchment might have been reused as a palimpsest, and also noted that the writing had chapter separators and dotted verse endings – features in Arabic scripts which are believed not to have been introduced to the Quran until later.[23] Dr Saud's criticisms was affirmed by several Saudi-based experts in Quranic history, who strongly rebut any speculation that the Birmingham/Paris Quran could have been written during the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad. They emphasize that while Muhammad was alive, Quranic texts were written without chapter decoration, marked verse endings or use of coloured inks; and did not follow any standard sequence of surahs. They maintain that those features were introduced into Quranic practice in the time of the Caliph Uthman, and so the Birmingham leaves could have been written later, but not earlier.[24]

Professor Süleyman Berk of the faculty of Islamic studies at Yalova University has noted the strong similarity between the script of the Birmingham leaves and those of a number of Hijazi Qurans in the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum; which were brought to Istanbul from the Great Mosque of Damascus following a fire in 1893. Professor Berk recalls that these manuscripts had been intensively researched in association with an exhibition on the history of the Quran, The Quran in its 1,400th Year held in Istanbul in 2010, and the findings published by François Déroche as Qur'ans of the Umayyads in 2013.[25] In that study, the Paris Quran, BnF Arabe 328(c), is compared with Qurans in Istanbul, and concluded as having been written "around the end of the seventh century and the beginning of the eighth century."[26]

In December 2015 Professor François Déroche of the Collège de France confirmed the identification of the two Birmingham leaves with those of the Paris Qur'an BnF Arabe 328(c), as had been proposed by Dr Alba Fedeli. Prof. Deroche expressed reservations about the reliability of the radiocarbon dates proposed for the Birmingham leaves, noting instances elsewhere in which radiocarbon dating had proved inaccurate in testing Qurans with an explicit endowment date; and also that none of the counterpart Paris leaves had yet been carbon-dated. Jamal bin Huwareib, managing director of the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Foundation, has proposed that, were the radiocarbon dates to be confirmed, the Birmingham/Paris Qur'an might be identified with the text known to have been assembled by the first Caliph Abu Bakr, between 632–634 CE.[27]

Further research and findings

Critical research of historic events and timeliness of eyewitness accounts reveal the effort of later traditionalists to consciously promote, for nationalistic purposes, the centrist concept of Mecca and prophetic descent from Ismail, in order to grant a Hijazi orientation to the emerging religious identity of Islam:

For, our attempt to date the relevant traditional material confirms on the whole the conclusions which Schacht arrived at from another field, specifically the tendency of isnads to grow backwards.[28]

In their book 1977 Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World, written before more recent discoveries of early Quranic material Patricia Crone and Michael Cook challenge the traditional account of how the Quran was compiled, writing that "there is no hard evidence for the existence of the Koran in any form before the last decade of the seventh century."[29][30] Crone, Wansbrough, and Nevo argued, that all the primary sources which exist are from 150–300 years after the events which they describe, and thus are chronologically far removed from those events.[31][32][33]

It is generally acknowledged that the work of Crone and Cook was a fresh approach in its reconstruction of early Islamic history, but the theory has been almost universally rejected.[34] Van Ess has dismissed it stating that "a refutation is perhaps unnecessary since the authors make no effort to prove it in detail ... Where they are only giving a new interpretation of well-known facts, this is not decisive. But where the accepted facts are consciously put upside down, their approach is disastrous."[35] R. B. Serjeant states that "[Crone and Cook's thesis]… is not only bitterly anti-Islamic in tone, but anti-Arabian. Its superficial fancies are so ridiculous that at first one wonders if it is just a 'leg pull', pure 'spoof'."[36] Francis Edward Peters states that "Few have failed to be convinced that what is in our copy of the Quran is, in fact, what Muhammad taught, and is expressed in his own words".[37]

In 2006, legal scholar Liaquat Ali Khan claimed that Crone and Cook later explicitly disavowed their earlier book.[38][39] Patricia Crone in an article published in 2006 provided an update on the evolution of her conceptions since the printing of the thesis in 1976. In the article she acknowledges that Muhammad existed as a historical figure and that the Quran represents "utterances" of his that he believed to be revelations. However she states that the Quran may not be the complete record of the revelations. She also accepts that oral histories and Muslim historical accounts cannot be totally discounted, but remains skeptical about the traditional account of the Hijrah and the standard view that Muhammad and his tribe were based in Mecca. She describes the difficulty in the handling of the hadith because of their "amorphous nature" and purpose as documentary evidence for deriving religious law rather than as historical narratives.[40]

The author of the Apology of al-Kindy Abd al-Masih ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (not the famed philosopher al-Kindi) claimed that the narratives in the Quran were "all jumbled together and intermingled" and that this was "an evidence that many different hands have been at work therein, and caused discrepancies, adding or cutting out whatever they liked or disliked".[41] Bell and Watt suggested that the variation in writing style throughout the Quran, which sometimes involves the use of rhyming, may have indicated revisions to the text during its compilation. They claimed that there were "abrupt changes in the length of verses; sudden changes of the dramatic situation, with changes of pronoun from singular to plural, from second to third person, and so on".[42] At the same time, however, they noted that "[i]f any great changes by way of addition, suppression or alteration had been made, controversy would almost certainly have arisen; but of that there is little trace." They also note that "Modern study of the Quran has not in fact raised any serious question of its authenticity. The style varies, but is almost unmistakable."[43]

A recent study has argued that the Quran we have today is exactly the same as the one compiled by 'Ali ibn Abi-Talib, and that the reading of Hafs from his teacher 'Asim to be the unaltered reading of 'Ali. This is because 'Asim's teacher, Abu 'Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami, had learned the Quran from 'Ali. Furthermore, Hafs was a Companion of Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq and it is claimed that the latter had inherited 'Ali's Master Copy of the Quran. The study provides a case that it was 'Ali's Master Copy which formed the basis of the 'Uthmanic canon. As for the reading of Hafs, the study presents evidence that the latter had learned the Quran from two sources: 'Asim who was his main teacher, and Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq who provided him with a corrective of 'Asim's reading. If future research can validate these preliminary findings, then this could very well mean that the reading of Hafs from Asim is the de facto reading of 'Ali which he inherited from the Prophet till the very last dot."[44]

Lack of secondary evidence and textual history

The traditional view of Islam has also been criticized for the lack of supporting evidence consistent with that view, such as the lack of archaeological evidence, and discrepancies with non-Muslim literary sources.[45] In the 1970s, what has been described as a "wave of skeptical scholars" challenged a great deal of the received wisdom in Islamic studies.[46]:23 They argued that the Islamic historical tradition had been greatly corrupted in transmission. They tried to correct or reconstruct the early history of Islam from other, presumably more reliable, sources such as coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic sources. The oldest of this group was John Wansbrough (1928–2002). Wansbrough's works were widely noted, but perhaps not widely read.[46]:38 In 1972 a cache of ancient Qurans in a mosque in Sana'a, Yemen was discovered – commonly known as the Sana'a manuscripts. On the basis of studies of the trove of Quranic manuscripts discovered in Sana’a, Gerd R. Puin concluded that the Quran as we have it is a ‘cocktail of texts’, some perhaps preceding Muhammad's day, and that the text as we have it evolved. He further claimed that, despite the assertion that is ‘mubeen’ (clear), one fifth of the text was incomprehensible and therefore could not be translated.[30]

Claim of divine origin

Critics reject the idea that the Quran is miraculously perfect and impossible to imitate (2:2, 17:88–89, 29:47, 28:49). The Jewish Encyclopedia, for example, writes: "The language of the Koran is held by the Mohammedans to be a peerless model of perfection. Critics, however, argue that peculiarities can be found in the text. For example, critics note that a sentence in which something is said concerning Allah is sometimes followed immediately by another in which Allah is the speaker (examples of this are suras xvi. 81, xxvii. 61, xxxi. 9, and xliii. 10.) Many peculiarities in the positions of words are due to the necessities of rhyme (lxix. 31, lxxiv. 3), while the use of many rare words and new forms may be traced to the same cause (comp. especially xix. 8, 9, 11, 16)."[47] According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, "The dependence of Mohammed upon his Jewish teachers or upon what he heard of the Jewish Haggadah and Jewish practices is now generally conceded."[47] Early jurists and theologians of Islam mentioned some Jewish influence but they also say where it is seen and recognized as such, it is perceived as a debasement or a dilution of the authentic message. Bernard Lewis describes this as "something like what in Christian history was called a Judaizing heresy."[48] Philip Schaff described the Quran as having "many passages of poetic beauty, religious fervor, and wise counsel, but mixed with absurdities, bombast, unmeaning images, low sensuality."[49]

According to Professor Moshe Sharon, a specialist in Arabic epigraphy, the legends about Muhammad having ten Jewish teachers developed in the 10th century CE:

In most versions of the legends, ten Jewish wise men or dignitaries appear, who joined Muhammad and converted to Islam for different reasons. In reading all the Jewish texts one senses the danger of extinction of the Jewish people; and it was this ominous threat that induced these Sages to convert...[50]

Preexisting sources

Günter Lüling asserts that one-third of the Quran has pre-Islamic Christian origins.[51] Puin likewise thinks some of the material predates Muhammad's life[30]

Scholar Oddbjørn Leirvik states "The Qur'an and Hadith have been clearly influenced by the non-canonical ('heretical') Christianity that prevailed in the Arab peninsula and further in Abyssinia" prior to Islam.[52]

When looking at the narratives of Jesus found in the Quran, some themes are found in pre-Islamic sources such as the Infancy Gospels about Christ.[53] Much of the quranic material about the selection and upbringing of Mary parallels much of the Protovangelium of James,[54] with the miracle of the palm tree and the stream of water being found in the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew.[54] In Pseudo-Matthew, the flight to Egypt is narrated similarly to how it is found in Islamic lore,[54] with Syriac translations of the Protoevangelium of James and The Infancy Story of Thomas being found in pre-Islamic sources.[54]

John Wansbrough believes that the Quran is a redaction in part of other sacred scriptures, in particular the Judaeo-Christian scriptures.[55][56] Herbert Berg writes that "Despite John Wansbrough's very cautious and careful inclusion of qualifications such as 'conjectural,' and 'tentative and emphatically provisional', his work is condemned by some. Some of the negative reaction is undoubtedly due to its radicalness... Wansbrough's work has been embraced wholeheartedly by few and has been employed in a piecemeal fashion by many. Many praise his insights and methods, if not all of his conclusions."[57] Gerd R. Puin's study of ancient Quran manuscripts led him to conclude that some of the Quranic texts may have been present a hundred years before Muhammad.[29] Norman Geisler argues that the dependence of the Quran on preexisting sources is one evidence of a purely human origin.[58]

Ibn Ishaq, an Arab Muslim historian and hagiographer who collected oral traditions that formed the basis of the important biography of Muhammad, also claimed that as a result of these discussions, the Quran was revealed addressing all these arguments – leading to the conclusion that Muhammad may have incorporated Judeo-Christian tales he had heard from other people. For example, in al-Sirah an-Nabawiyyah (an edited version of Ibn Ishaq's original work), Ibn Hishām's report

explains that the Prophet used often to sit at the hill of Marwa inviting a Christian...but they actually also would have had some resources with which to teach the Prophet.[59] ...saw the Prophet speaking with him, they said: "Indeed, he is being taught by Abu Fukayha Yasar." According to another version: "The apostle used often to sit at al-Marwa at the booth of a young Christian slave Jabr, slave of the Banu l-Hadrami, and they used to say: 'The one who teaches Muhammad most of what he brings is Jabr the Christian, slave of the Banu l-Hadrami."[60]

A study of informant reports by Claude Gilliot concluded the possibility that whole sections of the Meccan Quran contains elements from or within groups possessing Biblical, post-Biblical and other sources.[61] One such report and likely informant of Muhammad was the Christian slave mentioned in Sahih Bukhari whom Ibn Ishaq named as Jabr for which the Quran's chapter 16: 101–104 was probably revealed.[61] Waqidi names this Christian as Ibn Qumta,[62] with his identity and religious affiliation being contradicted in informant reports.[61] Ibn Ishaq also recounts the story of how three Christians, Abu Haritha Ibn `Alqama, Al-`Aqib `Abdul-Masih and Al-Ayham al-Sa`id, spoke to Muhammad regarding such Christian subjects as the Trinity.[63]

The narration of the baby Jesus speaking from the cradle can be traced back to the Arabic Infancy Gospel, and the miracle of the bringing clay birds to life being found in The Infancy Story of Thomas.[54]

Several narratives rely on Jewish Midrash Tanhuma legends, like the narrative of Cain learning to bury the body of Abel in Surah 5:31.[64][65] Richard Carrier regards this reliance on pre-Islamic Christian sources, as evidence that Islam derived from a heretical sect of Christianity.[66]

Influence of heretical Christian sects

The Quran maintains that Jesus was not actually crucified and did not die on the cross. The general Islamic view supporting the denial of crucifixion was probably influenced by Manichaenism (Docetism), which holds that someone else was crucified instead of Jesus, while concluding that Jesus will return during the end-times.[67] However the general consensus is that Manichaeism was not prevalent in Mecca in the 6th- & 7th centuries, when Islam developed.[68][69][70]

That they said (in boast), "We killed Christ Jesus the son of Mary, the Messenger of Allah";- but they killed him not, nor crucified him, but so it was made to appear to them, and those who differ therein are full of doubts, with no (certain) knowledge, but only conjecture to follow, for of a surety they killed him not:-

Nay, Allah raised him up unto Himself; and Allah is Exalted in Power, Wise;-

Despite these views and no eyewitness accounts, most modern scholars have maintained that the Crucifixion of Jesus is indisputable.[72][73]

The view that Jesus only appeared to be crucified and did not actually die predates Islam, and is found in several apocryphal gospels.[74]

Irenaeus in his book Against Heresies describes Gnostic beliefs that bear remarkable resemblance with the Islamic view:

He did not himself suffer death, but Simon, a certain man of Cyrene, being compelled, bore the cross in his stead; so that this latter being transfigured by him, that he might be thought to be Jesus, was crucified, through ignorance and error, while Jesus himself received the form of Simon, and, standing by, laughed at them. For since he was an incorporeal power, and the Nous (mind) of the unborn father, he transfigured himself as he pleased, and thus ascended to him who had sent him, deriding them, inasmuch as he could not be laid hold of, and was invisible to all.-

— Against Heresies, Book I, Chapter 24, Section 40

Another Gnostic writing, found in the Nag Hammadi library, Second Treatise of the Great Seth has a similar view of Jesus' death:

I was not afflicted at all, yet I did not die in solid reality but in what appears, in order that I not be put to shame by them

and also:

Another, their father, was the one who drank the gall and the vinegar; it was not I. Another was the one who lifted up the cross on his shoulder, who was Simon. Another was the one on whom they put the crown of thorns. But I was rejoicing in the height over all the riches of the archons and the offspring of their error and their conceit, and I was laughing at their ignorance

Coptic Apocalypse of Peter, likewise, reveals the same views of Jesus' death:

I saw him (Jesus) seemingly being seized by them. And I said 'What do I see, O Lord? That it is you yourself whom they take, and that you are grasping me? Or who is this one, glad and laughing on the tree? And is it another one whose feet and hands they are striking?' The Savior said to me, 'He whom you saw on the tree, glad and laughing, this is the living Jesus. But this one into whose hands and feet they drive the nails is his fleshly part, which is the substitute being put to shame, the one who came into being in his likeness. But look at him and me.' But I, when I had looked, said 'Lord, no one is looking at you. Let us flee this place.' But he said to me, 'I have told you, 'Leave the blind alone!'. And you, see how they do not know what they are saying. For the son of their glory instead of my servant, they have put to shame.' And I saw someone about to approach us resembling him, even him who was laughing on the tree. And he was with a Holy Spirit, and he is the Savior. And there was a great, ineffable light around them, and the multitude of ineffable and invisible angels blessing them. And when I looked at him, the one who gives praise was revealed.

Muhammad or God as speakers

According to Ibn Warraq, the Iranian rationalist Ali Dashti criticized the Quran on the basis that for some passages, "the speaker cannot have been God."[75] Warraq gives Surah Fatihah as an example of a passage which is "clearly addressed to God, in the form of a prayer."[75] He says that by only adding the word "say" in front of the passage, this difficulty could have been removed. Furthermore, it is also known that one of the companions of Muhammad, Ibn Masud, rejected Surah Fatihah as being part of the Quran; these kind of disagreements are, in fact, common among the companions of Muhammad who could not decide which surahs were part of the Quran and which not.[75] Quran is divided into two parts: the seven verses (Al-Fatiha) and Quran the great.

And we have given you seven often repeated verses and the great Quran. (Al-Quran 15:87)[76]

Cases where the speaker is swearing an oath by God, such as surahs 75:1–2 and 90:1, have been made a point of criticism.[77] But according to Richard Bell, this was probably a traditional formula, and Montgomery Watt compared such verses to Hebrews 6:13. It is also widely acknowledged that the first-person plural pronoun in Surah 19:64 refers to angels, describing their being sent by God down to Earth. Bell and Watt suggest that this attribution to angels can be extended to interpret certain verses where the speaker is not clear.[77]

Science in the Quran

Muslims and non-Muslims have disputed the presence of scientific miracles in the Quran. According to author Ziauddin Sardar, "popular literature known as ijaz" (miracle) has created a "global craze in Muslim societies", starting the 1970s and 80s and now found in Muslim bookstores, spread by websites and television preachers.[78]

Ijaz literature tends to follow a pattern of finding some possible agreement between a scientific result and a verse in the Quran. "So verily I swear by the stars that run and hide ..." (Q.81:15-16) or "And I swear by the stars' positions-and that is a mighty oath if you only knew". (Qur'an, 56:75-76)[79] is declared to refer to black holes; "[I swear by] the Moon in her fullness; that ye shall journey on from stage to stage" (Q.84:18-19) refers to space travel,[78] and thus evidence the Quran has miraculously predicted this phenomenon centuries before scientists.

While it is generally agreed the Quran contains many verses proclaiming the wonders of nature — “Travel throughout the earth and see how He brings life into being” (Q.29:20) “Behold in the creation of the heavens and the earth, and the alternation of night and day, there are indeed signs for men of understanding ...” (Q.3:190) — it is strongly doubted by Sardar and others that "everything, from relativity, quantum mechanics, Big Bang theory, black holes and pulsars, genetics, embryology, modern geology, thermodynamics, even the laser and hydrogen fuel cells, have been ‘found’ in the Quran”.[78][80]

Quranic verses related to the origin of mankind created from dust or mud are not logically compatible with modern evolutionary theory.[81][82] Although some Muslims try to reconcile evolution with the Quran by the argument from Intelligent design, the Quran (and the hadiths) support the idea of creationism. This led to a contribution by Muslims to the creation vs. evolution debate.[83]

In modern times, many scholars assert that the Quran predicts many statements. Contrary to classical Islam, in which also scientists among Muslim commentators, notably al-Biruni, assigned to the Quran a separate and autonomous realm of its own and held that the Quran "does not interfere in the business of science nor does it infringe on the realm of science."[84] These medieval scholars argued for the possibility of multiple scientific explanations of the natural phenomena, and refused to subordinate the Quran to an ever-changing science.[84]

Abrogation

Naskh (نسخ) is an Arabic language word usually translated as "abrogation"; it shares the same root as the words appearing in the phrase al-nāsikh wal-mansūkh (الناسخ والمنسوخ, "the abrogater and the abrogated [verses]"). The concept of "abrogation" in the Quran is that God chose to reveal ayat (singular ayah; means a sign or miracle, commonly a verse in the Quran) that supersede earlier ayat in the same Quran. The abrogation means that the revelation about the stories of previous messengers cannot be used as legal basis because they are abrogated by more general verses of Quran. The central ayah that deals with abrogation is Surah 2:106:

- "We do not abrogate a verse or cause it to be forgotten except that We bring forth [one] better than it or similar to it. Do you not know that Allah is over all things competent?"[85]

Philip Schaff argues that the concept of abrogation was developed to "remove" contradictions found in the Quran:

- "It abounds in repetitions and contradictions, which are not removed by the convenient theory of abrogation."[49]

Muhammad Husayn Tabatabaei believes abrogation in Quranic verses is not an indication of contradiction but an indication of addition and supplementation. As an example he mentions 2:109[86] where -according to him- it clearly states the forgiveness is not permanent and soon there will be another command (through another verse) on this subject that completes the matter. He also mentions 4:15[86] where the abrogated verse indicates its temporariness.[87]

Other scholars; however, have translated the 'abrogation' verse differently and disagree with the mainstream view. Ghulam Ahmed Parwez in his Exposition of the Quran derived the following meaning from the verse 2:106, making it consistent with the overall content of the Quran:

- The Ahl-ul-Kitab (People of the Book) also question the need for a new revelation (Qur'an) when previous revelations from Allah exist. They further ask why the Qur'an contains injunctions contrary to the earlier Revelation (the Torah) if it is from Allah? Tell them that Our way of sending Revelation to successive anbiya (prophets) is that: Injunctions given in earlier revelations, which were meant only for a particular time, are replaced by other injunctions, and injunctions which were to remain in force permanently but were abandoned, forgotten or adulterated by the followers of previous anbiya are given again in their original form (22:52). And all this happens in accordance with Our laid down standards, over which We have complete control. Now this last code of life which contains the truth of all previous revelations (5:48), is complete in every respect (6:116), and will always be preserved (15:9), has been given [to mankind].[88]

Satanic verses

Some criticism of the Quran has revolved around two verses known as the "Satanic Verses". Some early Islamic histories recount that as Muhammad was reciting Sūra Al-Najm (Q.53), as revealed to him by the angel Gabriel, Satan deceived him to utter the following lines after verses 19 and 20: "Have you thought of Al-lāt and al-'Uzzā and Manāt the third, the other; These are the exalted Gharaniq, whose intercession is hoped for." The Allāt, al-'Uzzā and Manāt were three goddesses worshiped by the Meccans. These histories then say that these 'Satanic Verses' were repudiated shortly afterward by Muhammad at the behest of Gabriel.[89]

There are numerous accounts reporting the alleged incident, which differ in the construction and detail of the narrative, but they may be broadly collated to produce a basic account.[84] The different versions of the story are all traceable to one single narrator Muhammad ibn Ka'b, who was two generations removed from biographer Ibn Ishaq.[90] In its essential form, the story reports that Muhammad longed to convert his kinsmen and neighbors of Mecca to Islam. As he was reciting Sūra an-Najm,[91] considered a revelation by the angel Gabriel, Satan tempted him to utter the following lines after verses 19 and 20:

Have ye thought upon Al-Lat and Al-'Uzzá

and Manāt, the third, the other?

These are the exalted gharāniq, whose intercession is hoped for.

Allāt, al-'Uzzā and Manāt were three goddesses worshipped by the Meccans. Discerning the meaning of "gharāniq" is difficult, as it is a hapax legomenon (i.e. only used once in the text). Commentators wrote that it meant the cranes. The Arabic word does generally mean a "crane" – appearing in the singular as ghirnīq, ghurnūq, ghirnawq and ghurnayq, and the word has cousin forms in other words for birds, including "raven, crow" and "eagle".[92]

The subtext to the event is that Muhammad was backing away from his otherwise uncompromising monotheism by saying that these goddesses were real and their intercession effective. The Meccans were overjoyed to hear this and joined Muhammad in ritual prostration at the end of the sūrah. The Meccan refugees who had fled to Abyssinia heard of the end of persecution and started to return home. Islamic tradition holds that Gabriel chastised Muhammad for adulterating the revelation, at which point [Quran 22:52] is revealed to comfort him,

Never sent We a messenger or a prophet before thee but when He recited (the message) Satan proposed (opposition) in respect of that which he recited thereof. But Allah abolisheth that which Satan proposeth. Then Allah establisheth His revelations. Allah is Knower, Wise.

Muhammad took back his words and the persecution of the Meccans resumed. Verses [Quran 53:21] were given, in which the goddesses are belittled. The passage in question, from 53:19, reads:

Have ye thought upon Al-Lat and Al-'Uzza

And Manat, the third, the other?

Are yours the males and His the females?

That indeed were an unfair division!

They are but names which ye have named, ye and your fathers, for which Allah hath revealed no warrant. They follow but a guess and that which (they) themselves desire. And now the guidance from their Lord hath come unto them.

The incident of the Satanic Verses is put forward by some critics as evidence of the Quran's origins as a human work of Muhammad. Maxime Rodinson describes this as a conscious attempt to achieve a consensus with pagan Arabs, which was then consciously rejected as incompatible with Muhammad's attempts to answer the criticism of contemporary Arab Jews and Christians,[93] linking it with the moment at which Muhammad felt able to adopt a "hostile attitude" towards the pagan Arabs.[94] Rodinson writes that the story of the Satanic Verses is unlikely to be false because it was "one incident, in fact, which may be reasonably accepted as true because the makers of Muslim tradition would not have invented a story with such damaging implications for the revelation as a whole".[95] In a caveat to his acceptance of the incident, William Montgomery Watt, states: "Thus it was not for any worldly motive that Muhammad eventually turned down the offer of the Meccans, but for a genuinely religious reason; not for example, because he could not trust these men nor because any personal ambition would remain unsatisfied, but because acknowledgment of the goddesses would lead to the failure of the cause, of the mission he had been given by God."[96] Academic scholars such as William Montgomery Watt and Alfred Guillaume argued for its authenticity based upon the implausibility of Muslims fabricating a story so unflattering to their prophet. Watt says that "the story is so strange that it must be true in essentials."[97] On the other hand, John Burton rejected the tradition.

In an inverted culmination of Watt's approach, Burton argued the narrative of the "satanic verses" was forged, based upon a demonstration of its actual utility to certain elements of the Muslim community – namely, those elite sections of society seeking an "occasion of revelation" for eradicatory modes of abrogation.[98] Burton's argument is that such stories served the vested interests of the status-quo, allowing them to dilute the radical messages of the Quran. The rulers used such narratives to build their own set of laws which contradicted the Quran, and justified it by arguing that not all of the Quran is binding on Muslims. Burton also sides with Leone Caetani, who wrote that the story of the "satanic verses" should be rejected not only on the basis of isnad, but because "had these hadiths even a degree of historical basis, Muhammad's reported conduct on this occasion would have given the lie to the whole of his previous prophetic activity."[99] Eerik Dickinson also pointed out that the Quran's challenge to its opponents to prove any inconsistency in its content was pronounced in a hostile environment, also indicating that such an incident did not occur or it would have greatly damaged the Muslims.[100]

Intended audience

Some verses of the Quran are assumed to be directed towards all of Muhammad's followers while other verses are directed more specifically towards Muhammad and his wives, yet others are directed towards the whole of humanity. (33:28, 33:50, 49:2, 58:1, 58:9 66:3).

Other scholars argue that variances in the Quran's explicit intended audiences are irrelevant to claims of divine origin – and for example that Muhammad's wives "specific divine guidance, occasioned by their proximity to the Prophet (Muhammad)" where "Numerous divine reprimands addressed to Muhammad's wives in the Quran establish their special responsibility to overcome their human frailties and ensure their individual worthiness",[101] or argue that the Quran must be interpreted on more than one level.[102] (See:[103]).

Jurisprudence

British-German professor of Arabic and Islam Joseph Schacht, in his work The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence (1950) regarding the subject of law derived from the Quran, wrote:

"Muhammadan [Islamic] law did not derive directly from the Koran but developed ...out of popular and administrative practice under the Umaiyads, and this practice often diverged from the intentions and even the explicit wording of the Koran .... Norms derived from the Koran were introduced into Muhammadan law almost invariably at a secondary stage."[104]

Schacht further states that every legal tradition from the Prophet must be taken as an inauthentic and fictitious expression of a legal doctrine formulated at a later date:

"... We shall not meet any legal tradition from the Prophet which can positively be considered authentic."[105]

What is evident regarding the compilation of the Quran is the disagreement between the companions of Muhammad (earliest supporters of Muhammad), as evidenced with their several disagreements regarding interpretation and particular versions of the Quran and their interpretative Hadith and Sunna, namely the mutawatir mushaf having come into present form after Muhammad's death.[106] John Burton's work The Collection of the Quran further explores how certain Quranic texts were altered to adjust interpretation, in regards to controversy between fiqh (human understanding of Sharia) and madhahib.[107]

Quality

Thomas Carlyle, after reading Sale's translation, called the Quran "toilsome reading and a wearisome confused jumble, crude, incondite" with "endless iterations, long-windedness, entanglement" and "insupportable stupidity." He said it is the work of a "great rude human soul".[108] Gerd Rüdiger Puin noted that approximately every fifth sentence of it does not make any sense despite the Quran's own claim of being a clear book.[109] Salomon Reinach wrote that this book warrants little merit from a literary point of view.[110]

Morality

According to some critics, the morality of the Quran, like the life story of Muhammad, appears to be a moral regression, by the standards of the moral traditions of Judaism and Christianity it says that it builds upon. The Catholic Encyclopedia, for example, states that "the ethics of Islam are far inferior to those of Judaism and even more inferior to those of the New Testament" and "that in the ethics of Islam there is a great deal to admire and to approve, is beyond dispute; but of originality or superiority, there is none."[111] William Montgomery Watt however finds Muhammad's changes an improvement for his time and place: "In his day and generation Muhammad was a social reformer, indeed a reformer even in the sphere of morals. He created a new system of social security and a new family structure, both of which were a vast improvement on what went before. By taking what was best in the morality of the nomad and adapting it for settled communities, he established a religious and social framework for the life of many races of men."[112]

The Sword verse:-

[9:5] Then, when the sacred months have passed, slay the idolaters wherever ye find them, and take them (captive), and besiege them, and prepare for them each ambush. But if they repent and establish worship and pay the zakat, then leave their way free. Lo! Allah is Forgiving, Merciful.[Quran 9:5–5 (Translated by Pickthall)]

According to the E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume 4, the term first applied in the Quran to unbelieving Meccans, who endeavoured "to refute and revile the Prophet". A waiting attitude towards the kafir was recommended at first for Muslims; later, Muslims were ordered to keep apart from unbelievers and defend themselves against their attacks and even take the offensive.[113] Most passages in the Quran referring to unbelievers in general talk about their fate on the day of judgement and destination in hell.[113]

"Lo! those who disbelieve (Kafir), among the People of the Scripture and the idolaters, will abide in fire of hell. They are the worst of created beings."[Quran 98:6]

Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859), a French political thinker and historian, observed:

I studied the Quran a great deal. I came away from that study with the conviction that by and large there have been few religions in the world as deadly to men as that of Muhammad. As far as I can see, it is the principal cause of the decadence so visible today in the Muslim world and, though less absurd than the polytheism of old, its social and political tendencies are in my opinion more to be feared, and I therefore regard it as a form of decadence rather than a form of progress in relation to paganism.[114]

War and peace

The Quran's teachings on matters of war and peace are topics that are widely debated. On the one hand, some critics, such as Sam Harris, interpret that certain verses of the Quran sanction military action against unbelievers as a whole both during the lifetime of Muhammad and after. Harris argues that Muslim extremism is simply a consequence of taking the Quran literally, and is skeptical about significant reform toward a "moderate Islam" in the future.[115][116] On the other hand, other scholars argue that such verses of the Quran are interpreted out of context,[117][118] and Muslims of the Ahmadiyya movement argue that when the verses are read in context it clearly appears that the Quran prohibits aggression,[119][120][121] and allows fighting only in self-defense.[122][123]

The author Syed Kamran Mirza has argued that a concept of 'Jihad', defined as 'struggle', has been introduced by the Quran. He wrote that while Muhammad was in Mecca, he "did not have many supporters and was very weak compared to the Pagans", and "it was at this time he added some 'soft', peaceful verses", whereas "almost all the hateful, coercive and intimidating verses later in the Quran were made with respect to Jihad" when Muhammad was in Medina .[124]

Micheline R. Ishay has argued that "the Quran justifies wars for self-defense to protect Islamic communities against internal or external aggression by non-Islamic populations, and wars waged against those who 'violate their oaths' by breaking a treaty".[125] Mufti M. Mukarram Ahmed has also argued that the Quran encourages people to fight in self-defense. He has also argued that the Quran has been used to direct Muslims to make all possible preparations to defend themselves against enemies.[126]

Shin Chiba and Thomas J. Schoenbaum argue that Islam "does not allow Muslims to fight against those who disagree with them regardless of belief system", but instead "urges its followers to treat such people kindly".[127] Yohanan Friedmann has argued that the Quran does not promote fighting for the purposes of religious coercion, although the war as described is "religious" in the sense that the enemies of the Muslims are described as "enemies of God".[128]

Rodrigue Tremblay has argued that the Quran commands that non-Muslims under a Muslim regime, should "feel themselves subdued" in "a political state of subservience" . He also argues that the Quran may assert freedom within religion.[129] Nisrine Abiad has argued that the Quran incorporates the offence (and due punishment) of "rebellion" into the offence of "highway or armed robbery".[130]

George W. Braswell has argued that the Quran asserts an idea of Jihad to deal with "a sphere of disobedience, ignorance and war".[131]

Michael David Bonner has argued that the "deal between God and those who fight is portrayed as a commercial transaction, either as a loan with interest, or else as a profitable sale of the life of this world in return for the life of the next", where "how much one gains depends on what happens during the transaction", either "paradise if slain in battle, or victory if one survives".[132] Critics have argued that the Quran "glorified Jihad in many of the Medinese suras" and "criticized those who fail(ed) to participate in it".[133]

Ali Ünal has claimed that the Quran praises the companions of Muhammad, for being stern and implacable against the said unbelievers, where in that "period of ignorance and savagery, triumphing over these people was possible by being strong and unyielding."[134]

Solomon Nigosian concludes that the "Quranic statement is clear" on the issue of fighting in defense of Islam as "a duty that is to be carried out at all costs", where "God grants security to those Muslims who fight in order to halt or repel aggression".[135]

Shaikh M. Ghazanfar argues that the Quran has been used to teach its followers that "the path to human salvation does not require withdrawal from the world but rather encourages moderation in worldly affairs", including fighting.[136] Shabbir Akhtar has argued that the Quran asserts that if a people "fear Muhammad more than they fear God, 'they are a people lacking in sense'" rather than a fear being imposed upon them by God directly.[137]

Various calls to arms were identified in the Quran by US citizen Mohammed Reza Taheri-azar, all of which were cited as "most relevant to my actions on March 3, 2006".[138]

Violence against women

Verse 4:34 of the Quran as translated by Ali Quli Qara'i reads:

- Men are the managers of women, because of the advantage Allah has granted some of them over others, and by virtue of their spending out of their wealth. So righteous women are obedient, care-taking in the absence [of their husbands] of what Allah has enjoined [them] to guard. As for those [wives] whose misconduct you fear, [first] advise them, and [if ineffective] keep away from them in the bed, and [as the last resort] beat them. Then if they obey you, do not seek any course [of action] against them. Indeed, Allah is all-exalted, all-great.[139]

Many translations do not necessarily imply a chronological sequence, for example, Marmaduke Pickthall's, Muhammad Muhsin Khan's, or Arthur John Arberry's. Arberry's translation reads "admonish; banish them to their couches, and beat them."[140]

The Dutch film Submission, which rose to fame outside the Netherlands after the assassination of its director Theo van Gogh by Muslim extremist Mohammed Bouyeri, critiqued this and similar verses of the Quran by displaying them painted on the bodies of abused Muslim women.[141] Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the film's writer, said "it is written in the Koran a woman may be slapped if she is disobedient. This is one of the evils I wish to point out in the film".[142]

Scholars of Islam have a variety of responses to these criticisms. (See An-Nisa, 34 for a fuller exegesis on the meaning of the text.) Some Muslim scholars say that the "beating" allowed is limited to no more than a light touch by siwak, or toothbrush.[143][144] Some Muslims argue that beating is only appropriate if a woman has done "an unrighteous, wicked and rebellious act" beyond mere disobedience.[145] In many modern interpretations of the Quran, the actions prescribed in 4:34 are to be taken in sequence, and beating is only to be used as a last resort.[146][147][148]

Many Islamic scholars and commentators have emphasized that beatings, where permitted, are not to be harsh[149][150][151] or even that they should be "more or less symbolic."[152] According to Abdullah Yusuf Ali and Ibn Kathir, the consensus of Islamic scholars is that the above verse describes a light beating.[153][154]

Some jurists argue that even when beating is acceptable under the Quran, it is still discountenanced.[155][156][157]

Shabbir Akhtar has argued that the Quran introduced prohibitions against "the pre-Islamic practice of female infanticide" (16:58, 17:31, 81:8).[158]

Houris

Max I. Dimont interprets that the Houris described in the Quran are specifically dedicated to "male pleasure".[159]

Alternatively, Annemarie Schimmel says that the Quranic description of the Houris should be viewed in a context of love; "every pious man who lives according to God's order will enter Paradise where rivers of milk and honey flow in cool, fragrant gardens and virgin beloveds await home..."[160]

Under the Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Quran by Christoph Luxenberg, the words translating to "Houris" or "Virgins of Paradise" are instead interpreted as "Fruits (grapes)" and "high climbing (wine) bowers... made into first fruits."[161] Luxemberg offers alternate interpretations of these Quranic verses, including the idea that the Houris should be seen as having a specifically spiritual nature rather than a human nature; "these are all very sensual ideas; but there are also others of a different kind... what can be the object of cohabitation in Paradise as there can be no question of its purpose in the world, the preservation of the race. The solution of this difficulty is found by saying that, although heavenly food, women etc.., have the name in common with their earthly equivalents, it is only by way of metaphorical indication and comparison without actual identity... authors have spiritualized the Houris."[161]

Christians and Jews in the Quran

Jane Gerber claims that the Quran ascribes negative traits to Jews, such as cowardice, greed, and chicanery. She also alleges that the Quran associates Jews with interconfessional strife and rivalry (Quran 2:113), the Jewish belief that they alone are beloved of God (Quran 5:18), and that only they will achieve salvation (Quran 2:111).[162] According to the Encyclopedia Judaica, the Quran contains many attacks on Jews and Christians for their refusal to recognize Muhammad as a prophet.[163] In the Muslim view, the crucifixion of Jesus was an illusion, and thus the Jewish plots against him ended in failure.[164] In numerous verses[165] the Quran accuses Jews of altering the Scripture.[166] Karen Armstrong claims that there are "far more numerous passages in the Quran" which speak positively of the Jews and their great prophets, than those which were against the "rebellious Jewish tribes of Medina" (during Muhammad's time).[167] Sayyid Abul Ala believes the punishments were not meant for all Jews, and that they were only meant for the Jewish inhabitants that were sinning at the time.[167] According to historian John Tolan, the Quran contains a verse which criticizes the Christian worship of Jesus Christ as God, and also criticizes other practices and doctrines of both Judaism and Christianity. Despite this, the Quran has high praise for these religions, regarding them as the other two parts of the Abrahamic trinity.[168]

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity states that God is a single being who exists, simultaneously and eternally, as a communion of three distinct persons, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. In Islam such plurality in God is a denial of monotheism and thus a sin of shirk,[169] which is considered to be a major 'al-Kaba'ir' sin.[170][171]

Hindu criticism

Hindu Swami Dayanand Saraswati gave a brief analysis of the Quran in the 14th chapter of his 19th-century book Satyarth Prakash. He calls the concept of Islam highly offensive, and doubted that there is any connection of Islam with God:

Had the God of the Quran been the Lord of all creatures, and been Merciful and kind to all, he would never have commanded the Muhammedans to slaughter men of other faiths, and animals, etc. If he is Merciful, will he show mercy even to the sinners? If the answer be given in the affirmative, it cannot be true, because further on it is said in the Quran "Put infidels to sword," in other words, he that does not believe in the Quran and the Prophet Mohammad is an infidel (he should, therefore, be put to death). Since the Quran sanctions such cruelty to non-Muhammedans and innocent creatures such as cows it can never be the Word of God.[172]

On the other hand, Mahatma Gandhi, the moral leader of the 20th-century Indian independence movement, found the Quran to be peaceful, but the history of Muslims to be aggressive, while he claimed that Hindus have passed that stage of societal evolution:

Though, in my opinion, non-violence has a predominant place in the Quran, the thirteen hundred years of imperialistic expansion has made the Muslims fighters as a body. They are therefore aggressive. Bullying is the natural excrescence of an aggressive spirit. The Hindu has an ages old civilization. He is essentially non violent. His civilization has passed through the experiences that the two recent ones are still passing through. If Hinduism was ever imperialistic in the modern sense of the term, it has outlived its imperialism and has either deliberately or as a matter of course given it up. Predominance of the non-violent spirit has restricted the use of arms to a small minority which must always be subordinate to a civil power highly spiritual, learned and selfless.[173][174]

See also

- Creation–evolution controversy

- Islam and science

- Islam: What the West Needs to Know

- The Syro-Aramaic Reading Of The Koran

- War against Islam

- Criticism

- Apostasy in Islam

- Censorship by religion

- Child marriage

- Criticism of Hadith

- Criticism of Islam

- Criticism of Muhammad

- Homosexuality and Islam

- Islam and antisemitism

- Islam and domestic violence

- Islamic terrorism

- Islamic views on slavery

- Islamofascism

- Women in Islam

- Controversies

- Islamic view of Ezra, concerns Al-Quran 9:30 which quotes, "and Jews said Ezra (Uzair) is the son of God"

References

- Donner, "Quran in Recent Scholarship", 2008: p.29

- LESTER, TOBY (January 1999). "What Is the Koran?". Atlantic. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Bible in Mohammedian Literature., by Kaufmann Kohler Duncan B. McDonald, Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 22, 2006.

- John Esposito, Islam the Straight Path, Extended Edition, p.19-20

- Christoph Luxenberg The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran: A Contribution to the Decoding of the Language of the Koran. Verlag Hans Schiler, 2007 ISBN 978-3-899-30088-8 p.31.

- Christoph Luxenberg, 2007 p.36

- e.g. Gerald Hawting, interviewed for The Religion Report, Radio National (Australia), 26 June 2002.

- Joel L. Kraemer Israel Oriental Studies XII BRILL 1992 ISBN 9789004095847 p. 41

- Lawson, Todd (1 March 2009). The Crucifixion and the Quran: A Study in the History of Muslim Thought. Oneworld Publications. p. 12. ISBN 1851686355.

- Eddy, Paul Rhodes and Gregory A. Boyd (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Baker Academic. p. 172. ISBN 0801031141. ...if there is any fact of Jesus' life that has been established by a broad consensus, it is the fact of Jesus' crucifixion.

- (Burton, pp. 141–42 – citing Ahmad b. `Ali b. Muhammad al `Asqalani, ibn Hajar, "Fath al Bari", 13 vols, Cairo, 1939/1348, vol. 9, p. 18).

- Bucaille, Dr. Maurice (1977). The Bible, the Quran, and Science: The Holy Scriptures Examined in the Light of Modern Knowledge. TTQ, INC.f. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-879402-98-0.

- Muir, The Life of Mahomet, 3rd Edition, Indian Reprint, New Delhi, 1992, pp. 41–42.

- Ahmad b. Ali b. Muhammad al 'Asqalani, ibn Hajar, Fath al Bari [13 vol., Cairo 1939], vol. 9, p. 9.

- John Gilchrist, Jam' Al-Qur'an. The Codification of the Qur'an Text A Comprehensive Study of the Original Collection of the Qur'an Text and the Early Surviving Qur'an Manuscripts, [MERCSA, Mondeor, 2110 Republic of South Africa, 1989], Chapter 1. "The Initial Collection of the Qur'an Text", p. 27 – citing Ibn Abi Dawud, Kitab al-Masahif, p. 5.

- (Ibid., citing as-Suyuti, Al-Itqan fii Ulum al-Qur'an, p. 135).

- Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 8.

- "A Find in Britain: Quran Fragments Perhaps as Old as Islam".

- Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 26.

- Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 23.

- Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 20.

- Lumbard, Joseph. "New Light on the History of the Quranic Text?". HuffPost. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Dan Bilefsky (22 July 2015), "A Find in Britain: Quran Fragments Perhaps as Old as Islam", The New York Times

- "Experts doubt oldest Quran claim". Saudi Gazette. 27 July 2015. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Déroche, François (2013). Qur'ans of the Umayyads: a first overview. Brill Publishers. pp. 67–69.

- "Oldest Quran still a matter of controversy". Daily Sabah. 27 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- "Birmingham's ancient Koran history revealed". BBC. 23 December 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- J. Schacht, The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence, London, 1950, pp. 107, 156.

- Patricia Crone, Michael Cook, and Gerd R. Puin as quoted in Toby Lester (January 1999). "What Is the Koran?". The Atlantic Monthly.

- Toby Lester 'What Is the Koran?,' The Atlantic Monthly January 1999

- Yehuda D. Nevo "Towards a Prehistory of Islam," Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, vol. 17, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1994 p. 108.

- John Wansbrough The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1978 p. 119

- Patricia Crone, Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam, Princeton University Press, 1987 p. 204.

- David Waines, Introduction to Islam, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-42929-3, pp. 273–74

- van Ess, "The Making Of Islam", Times Literary Supplement, Sep 8 1978, p. 998

- R. B. Serjeant, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1978) p. 78

- Peters, F. E. (Aug., 1991) "The Quest of the Historical Muhammad." International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 291–315.

- Liaquat Ali Khan. "Hagarism: The Story of a Book Written by Infidels for Infidels". Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- Liaquat Ali Khan. "Hagarism: The Story of a Book Written by Infidels for Infidels". Retrieved 2006-06-09.

- "What do we actually know about Mohammed?". openDemocracy. 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- Quoted in A. Rippin, Muslims: their religious beliefs and practices: Volume 1, London, 1991, p. 26

- R. Bell & W.M. Watt, An introduction to the Quran, Edinburgh, 1977, p. 93

- Bell's introduction to the Qurʼān. By Richard Bell, William Montgomery Watt, p. 51: Google preview

- New Light on the Collection and Authenticity of the Qur'an: The Case for the Existence of a Master Copy and how it Relates to the Reading of Hafs ibn Sulayman from 'Asim ibn Abi al-Nujud, By Ahmed El-Wakil:

- "What do we actually know about Mohammed?". openDemocracy. Archived from the original on 2009-04-21. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- Donner, Fred Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing, Darwin Press, 1998

- "Koran". From the Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- Jews of Islam, Bernard Lewis, p. 70: Google Preview

- Schaff, P., & Schaff, D. S. (1910). History of the Christian church. Third edition. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Volume 4, Chapter III, section 44 "The Koran, And The Bible"

- Studies in Islamic History and Civilization, Moshe Sharon, p. 347: Google Preview

- G. Luling asserts that a third of the Quran is of pre-Islamic Christian origins, see Uber den Urkoran, Erlangen, 1993, 1st Ed., 1973, p. 1.

- Leirvik, Oddbjørn (27 May 2010). Images of Jesus Christ in Islam: 2nd Edition. New York: Bloomsbury Academic; 2nd edition. pp. 33–66. ISBN 1441181601.

- Leirvik 2010, p. 33.

- Leirvik 2010, pp. 33–34.

- Wansbrough, John (1977). Quranic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation

- Wansbrough, John (1978). The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History.

- Berg, Herbert (2000). The development of exegesis in early Islam: the authenticity of Muslim literature from the formative period. Routledge. pp. 83, 251. ISBN 0-7007-1224-0.

- Geisler, N. L. (1999). In Baker encyclopedia of Christian apologetics. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. Entry on Qur'an, Alleged Divine Origin of.

- Osman, Ghada (2005). "Foreign slaves in Mecca and Medina in the formative Islamic period". Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations. Routledge. 16 (4): 345–59. doi:10.1080/09596410500250230.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Sayeed (2 December 2007). The Qur'an in Its Historical Context. United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 041549169X.

- Reynolds 2007, p. 90.

- Warraq, Ibn (1 September 1998). The Origins of the Koran: Classic Essays on Islam's Holy Book. Prometheus Books. p. 102. ISBN 157392198X.

- Tisdall, William (1905). The Original Sources Of The Qur'an. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. pp. 180–81.

- Samuel A. Berman, Midrash Tanhuma-Yelammedenu (KTAV Publishing house, 1996) 31–32

- Gerald Friedlander, Pirḳe de-R. Eliezer, (The Bloch Publishing Company, 1916) 156

- https://www.richardcarrier.info/archives/8574

- Joel L. Kraemer Israel Oriental Studies XII BRILL 1992 ISBN 9789004095847 p. 41

- Manichaeism, by Michel Tardieu, translation by DeBevoise (2008), p 23-27.

- M. Tardieu, “Les manichéens en Egypte,” Bulletin de la Société Française d’Egyptologie 94, 1982,. & see M. Tardieu (1994),.

- "Manicheism v. Missionary Activity & Technique".

That Manicheism went further on to the Arabian peninsula, up to the Hejaz and Mecca, where it could have possibly contributed to the formation of the doctrine of Islam, cannot be proven. A detailed description of Manichean traces in the Arabian-speaking regions is given by Tardieu (1994).

- Lawson, Todd (1 March 2009). The Crucifixion and the Quran: A Study in the History of Muslim Thought. Oneworld Publications. p. 12. ISBN 1851686355.

- Eddy, Paul Rhodes and Gregory A. Boyd (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Baker Academic. p. 172. ISBN 0801031141. ...if there is any fact of Jesus' life that has been established by a broad consensus, it is the fact of Jesus' crucifixion.

- Klein, Christopher (26 February 2019). "The Bible Says Jesus Was Real. What Other Proof Exists?". History. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

Within a few decades of his lifetime, Jesus was mentioned by Jewish and Roman historians in passages that corroborate portions of the New Testament that describe the life and death of Jesus...The first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus...twice mentions Jesus in Jewish Antiquities...written around 93 A.D....Another account of Jesus appears in Annals of Imperial Rome...written around 116 A.D. by the Roman senator and historian Tacitus...Ehrman says this collection of snippets from non-Christian sources may not impart much information about the life of Jesus, ‘but it is useful for realizing that Jesus was known by historians who had reason to look into the matter. No one thought he was made up.’

- Joel L. Kraemer Israel Oriental Studies XII BRILL 1992 ISBN 9789004095847 p. 41

- Warraq. Why I am Not a Muslim (PDF). Prometheus Books. p. 106. ISBN 0-87975-984-4.

- "Quran Surah Al-Hijr (Verse 87) with English Translation وَلَقَدْ آتَيْنَاكَ سَبْعًا مِنَ الْمَثَانِي وَالْقُرْآنَ الْعَظِيمَ". IReBD.com.

- Bell, Richard; Watt, William Montgomery (1970). Bell's introduction to the Qurʼān. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-0-7486-0597-2., and note.10

- SARDAR, ZIAUDDIN (21 August 2008). "Weird science". New Statesman. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- "BLACK HOLES". miracles of the quran. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- TALIB, ALI (9 April 2018). "Deconstructing the "Scientific Miracles in the Quran" Argument". Transversing Tradition. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Saleem, Shehzad (May 2000). "The Quranic View on Creation". Renaissance. 10 (5). ISSN 1606-9382. Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- Ahmed K. Sultan Salem Evolution in the Light of Islam

- Paulson, Steve Seeing the light – of science

- Ahmed, Shahab (2008), "Satanic Verses", in Dammen McAuliffe, Jane (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, Georgetown University, Washington DC: Brill (published 14 August 2008)

- "Surat Al-Baqarah 2:106] – The Noble Qur'an – القرآن الكريم". Quran.com. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- "Surat Al-Baqarah 2:109] – The Noble Qur'an – القرآن الكريم". Quran.com. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- Al-Mizan, Muhammad Husayn Tabatabayei, commentation on 2:106 translation available here "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2012-03-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Exposition of the Holy Quran – Ghulam Ahmad Parwez – Tolue Islam Trust". tolueislam.org. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- "The Life of Muhammad", Ibn Ishaq, A. Guillaume (translator), 2002, p. 166 ISBN 0-19-636033-1

- Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad (1955). Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah – The Life of Muhammad Translated by A. Guillaume. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 165. ISBN 9780196360331.

- (Q.53)

- Militarev, Alexander; Kogan, Leonid (2005), Semitic Etymological Dictionary 2: Animal Names, Alter Orient und Altes Testament, 278/2, Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, pp. 131–32, ISBN 3-934628-57-5

- Maxime Rodinson, Muhammad (Tauris Parke, London, 2002) (ISBN 1-86064-827-4) pp. 107–08.

- Maxime Rodinson, Muhammad (Tauris Parke, London, 2002) (ISBN 1-86064-827-4) p. 113.

- Maxime Rodinson, Muhammad (Tauris Parke, London, 2002) (ISBN 1-86064-827-4) p. 106

- W. Montgomery Watt, Muhammad at Mecca, Oxford, 1953. 'The Growth of Opposition', p. 105

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1961). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-19-881078-4.

- John Burton (1970). "Those Are the High-Flying Cranes". Journal of Semitic Studies 15: 246–264.

- Quoted by I.R Netton in "Text and Trauma: An East-West Primer" (1996) p. 86, Routledge

- Eerik Dickinson, Difficult Passages, Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān

- Women in the Quran, traditions, and interpretation by Barbara Freyer, p. 85, Mothers of the Believers in the Quran

- Corbin (1993), p. 7

- Quran#Levels of meaning

- Joseph Schacht, The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence, Oxford, 1950, p. 224

- Joseph Schacht, The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence, Oxford, 1950, p. 149

- Burton, John (1979). The Collection of the Quran. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 0521214394.

- Burton 1979, pp. 29–30.

- Thomas Carlyle (1841), On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History, p. 64-67

- Lester, Toby (January 1999). "What Is the Koran?". Atlantic Monthly. ISSN 1072-7825. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- Reinach, Salomon (1909). Orpheus: A History of Religions.

From the literary point of view, the Koran has little merit. Declamation, repetition, puerility, a lack of logic and coherence strike the unprepared reader at every turn. It is humiliating to the human intellect to think that this mediocre literature has been the subject of innumerable commentaries, and that millions of men are still wasting time absorbing it.

- "Mohammed and Mohammedanism". From the Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- W Montgomery Watt, Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman, chapter "Assessment" section "The Alleged Moral Failures", Op. Cit, p. 332.

- Houtsma, M. Th (1993). E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume 4. Touchstone. p. 619. ISBN 9789004097902.

Tolerance may in no circumstances be extended to the apostate, the renegade Muslim, whose punishment is death. Some authorities allow the remission of this punishment if the apostate recants. Others insist on the death penalty even then. God may pardon him the world to come; the law must punish him in this world.

- Alexis de Tocqueville; Olivier Zunz, Alan S. Kahan (2002). The Tocqueville Reader. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 063121545X. OCLC 49225552. p.229.

- Harris, Sam (2005). The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason. W. W. Norton; Reprint edition. pp. 31, 149. ISBN 0-393-32765-5.

- Harris makes a similar argument about hadith, saying "[a]ccording to a literalist reading of the hadith (the literature that recounts the sayings and the actions of the Prophet) if a Muslim decides that he no longer wants to be a Muslim, he should be put to death. If anyone ventures the opinion that the Koran is a mediocre book of religious fiction or that Muhammad was a schizophrenic, he should also be killed. It should go without saying that a desire to kill people for imaginary crimes like apostasy and blasphemy is not an expression of religious moderation." "Who Are the Moderate Muslims?," The Huffington Post, February 16, 2006 (accessed 11/16/2013)

- Sohail H. Hashmi, David Miller, Boundaries and Justice: diverse ethical perspectives, Princeton University Press, p. 197

- Khaleel Muhammad, professor of religious studies at San Diego State University, states, regarding his discussion with the critic Robert Spencer, that "when I am told ... that Jihad only means war, or that I have to accept interpretations of the Quran that non-Muslims (with no good intentions or knowledge of Islam) seek to force upon me, I see a certain agendum developing: one that is based on hate, and I refuse to be part of such an intellectual crime." "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-07-08. Retrieved 2008-10-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ali, Maulana Muhammad; The Religion of Islam (6th Edition), Ch V "Jihad" p. 414 "When shall war cease". Published by The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement

- Sadr-u-Din, Maulvi. "Quran and War", p. 8. Published by The Muslim Book Society, Lahore, Pakistan.

- Article on Jihad by Dr. G. W. Leitner (founder of The Oriental Institute, UK) published in Asiatic Quarterly Review, 1886. ("jihad, even when explained as a righteous effort of waging war in self-defense against the grossest outrage on one's religion, is strictly limited..")

- The Quranic Commandments Regarding War/Jihad An English rendering of an Urdu article appearing in Basharat-e-Ahmadiyya Vol. I, pp. 228–32, by Dr. Basharat Ahmad; published by the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for the Propagation of Islam

- Ali, Maulana Muhammad; The Religion of Islam (6th Edition), Ch V "Jihad" pp. 411–13. Published by The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement

- Syed Kamran Mirza (2006). Kim Ezra Shienbaum; Jamal Hasan (eds.). An Exegesis on 'Jihad in Islam'. Beyond Jihad: Critical Voices from Inside Islam. Academica Press, LLC. pp. 78–80. ISBN 1-933146-19-2.

- Ishay, Micheline. The history of human rights. Berkeley: University of California. p. 45. ISBN 0-520-25641-7.

- Mufti M. Mukarram Ahmed (2005). Encyclopaedia of Islam – 25 Vols. New Delhi: Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 386–89. ISBN 81-261-2339-7.

- Schoenbaum, Thomas J.; Chiba, Shin (2008). Peace Movements and Pacifism After September 11. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 115–16. ISBN 1-84720-667-0.

- Friedmann, Yohanan (2003). Tolerance and coercion in Islam: interfaith relations in the Muslim tradition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 0-521-82703-5.

- Tremblay, Rodrigue (2009). The Code for Global Ethics: Toward a Humanist Civilization. Trafford Publishing. pp. 169–70. ISBN 1-4269-1358-3.

- Nisrine Abiad (2008). Sharia, Muslim States and International Human Rights Treaty Obligations: A Comparative Study. British Institute for International & Compara. p. 24. ISBN 1-905221-41-X.

- Braswell, George W.; Braswell, George W. Jr (2000). What you need to know about Islam & Muslims. Nashville, Tenn: Broadman & Holman Publishers. p. 38. ISBN 0-8054-1829-6.

- Bonner, Michael David (2006). Jihad in Islamic history: doctrines and practice. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. p. 32. ISBN 0-691-12574-0.

- Peters, Rudolph Albert (2008). Jihad in classical and modern Islam: a reader. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 46. ISBN 1-55876-359-7.

- Ali Unal (2008). The Quran with Annotated Interpretation in Modern English. Rutherford, N.J: The Light, Inc. p. 249. ISBN 1-59784-144-7.

- Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: its history, teaching, and practices. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21627-3.

- Ghazanfar, Shaikh M. (2003). Medieval Islamic economic thought: filling the "great gap" in European economics. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-29778-8.

- Akhtar, Shabbir (2008). The Quran and the secular mind: a philosophy of Islam. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-43783-0.

- Taheri-azar, Mohammed Reza (2006). – via Wikisource.

- "Surat An-Nisa' 4:34] – The Noble Qur'an – القرآن الكريم". al-quran.info/#4:34. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- Bernard Lewis A Middle East Mosaic: Fragments of Life, Letters and History (Modern Library, 2001) p. 184 ISBN 0375758372

- "Script for the movie, Submission". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2012-10-14.