Battle of Blair Mountain

The Battle of Blair Mountain was the largest labor uprising in United States history and the largest armed uprising since the American Civil War.[3] The conflict occurred in Logan County, West Virginia, as part of the Coal Wars, a series of early-20th-century labor disputes in Appalachia. Up to 100 people were killed, and many more arrested. The United Mine Workers saw major declines in membership, but the long-term publicity led to some improvements in working conditions.

For five days from late August to early September 1921, some 10,000 armed coal miners confronted 3,000 lawmen and strikebreakers (called the Logan Defenders)[4] who were backed by coal mine operators during the miners' attempt to unionize the southwestern West Virginia coalfields when tensions rose between workers and mine management. The battle ended after approximately one million rounds were fired[5] and the United States Army, represented by the West Virginia National Guard, intervened by presidential order.[6]

Background

On May 19, 1920, a dozen detectives from the Baldwin–Felts Detective Agency, including Lee Felts arrived in Matewan, West Virginia and connected with Lee’s brother Albert Felts. Albert and Lee were the brothers of Thomas Felts, the co-owner and director of the private detective agency. Albert had already been in the area and had tried to bribe Mayor Cabell Testerman with $500 to place machine guns on roofs in the town; Testerman refused.[7] That afternoon Albert and Lee along with 11 other men set out to the Stone Mountain Coal Co. property. The first family they evicted was a woman and her children; the woman's husband was not home at the time. They forced them out at gunpoint and threw their belongings in the road under a light but steady rain. The miners who saw it were furious, and sent word to town.[8]

As the agents walked to the train station to leave town, Police Chief Sid Hatfield and a group of deputized miners confronted them and told them they were under arrest. Albert Felts replied that in fact he had a warrant for Hatfield's arrest.[9] Testerman was alerted, and he ran out into the street after a miner shouted that Sid had been arrested. Hatfield backed into the store and Testerman asked to see the warrant. After reviewing it, the mayor exclaimed, "This is a bogus warrant." With these words, a gunfight erupted and Hatfield shot Albert Felts. Testerman and Albert and Lee Felts were among the ten men killed (three from the town and seven from the agency).[9]

This gunfight became known as the Matewan Massacre, and its symbolic significance was enormous for the miners. The seemingly invincible Baldwin-Felts had been beaten.[10] Sid Hatfield became an immediate legend and hero to the union miners, and a symbol of hope that the oppression of coal operators and their hired guns could be overthrown.[11] Throughout the summer and into the fall of 1920 the union gained strength in Mingo County, as did the resistance of the coal operators. Low-intensity warfare was waged up and down the Tug River. In late June state police under the command of Captain Brockus raided the Lick Creek tent colony near Williamson. Miners were said to have fired on Brockus and Martin's men from the colony, and in response the state police shot and arrested miners, ripped the canvas tents to shreds and scattered the mining families' belongings.[12] Both sides were bolstering their arms, and Sid Hatfield continued to be a problem, especially when he converted Testerman's jewelry store into a gun shop.[13]

On January 26, 1921, the trial of Hatfield for killing Albert Felts began. It was in the national spotlight and brought much attention to the miners' cause. Hatfield's stature and mythical status grew as the trial proceeded. He posed and talked to reporters, fanning the flames of his own legend. All men were acquitted in the end, but overall the union was facing significant setbacks.[14] Eighty percent of mines had reopened with the importation of replacements and the signing of yellow-dog contracts by ex-strikers returning to the mines.[15] In mid-May 1921 union miners launched a full-scale assault on non-union mines. In a short time the conflict had consumed the entire Tug River Valley. This "Three Days Battle" was finally ended by a flag of truce and the implementation of martial law.[16] From the beginning, the miners perceived the enforcement of martial law as one-sided.[17] Hundreds of miners were arrested; the smallest of infractions could mean imprisonment, while those on the side of "law and order" were seen as immune.[18] The miners responded with guerrilla tactics and violence.[18]

In the midst of this tense situation, Hatfield traveled to McDowell County on August 1, 1921 to stand trial on charges of dynamiting a coal tipple. Along with him traveled a good friend, Ed Chambers, and their wives.[19] As they walked up the courthouse stairs, unarmed and flanked by their wives, a group of Baldwin-Felts agents standing at the top of the stairs opened fire. Hatfield was killed instantly. Chambers was bullet-riddled and rolled to the bottom of the stairs. Despite Sally Chambers' protests, one of the agents ran down the stairs and shot Chambers once more, point-blank in the back of the head.[20] Hatfield's and Chambers' bodies were returned to Matewan, and word of the slayings spread through the mountains.

The miners were angry at the way Hatfield had been slain, and that it appeared the assassins would escape punishment.[21] They began to pour out of the mountains and take up arms.

Miners along the Little Coal River were among the first to militarize, and began actions such as patrolling and guarding the area. Sheriff Don Chafin sent Logan County troopers to the Little Coal River area, where armed miners captured the troopers, disarmed them and sent them fleeing.[22]

On August 7, 1921, the leaders of the United Mine Workers (UMW) District 17, which encompasses much of southern West Virginia, called a rally at the state capitol in Charleston. These leaders were Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney, who were veterans of previous mine conflicts in the region. Both were local, well-read and articulate. Keeney and Mooney met with Governor Ephraim Morgan and presented him with a petition of the miners' demands.[23] When Morgan summarily rejected the demands, the miners became more restless and began to talk of a march on Mingo to free the confined miners, end martial law and organize the county. But Blair Mountain, Logan County, and Sheriff Chafin stood directly in the way.[24]

Battle

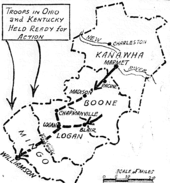

At a rally on August 7, Mary Harris "Mother" Jones called on the miners not to march into Logan and Mingo counties and set up the union by force. Accused by some of losing her nerve, she feared a bloodbath in a battle between lightly armed union forces and the more heavily armed Logan County deputies. Yet, feeling Morgan had lied to them again, armed men began gathering at Lens Creek Mountain, near Marmet in Kanawha County, on August 20. Four days later an estimated 13,000 had gathered and began marching towards Logan County. Impatient to get to the fighting, miners near St. Albans, in Kanawha County, commandeered a Chesapeake and Ohio freight train, renamed by the miners the Blue Steel Special, to meet up with the advanced column of marchers at Danville in Boone County on their way to "Bloody Mingo". During this time Keeney and Mooney fled to Ohio, while the fiery Bill Blizzard assumed quasi-leadership of the miners. Meanwhile, the anti-union Sheriff Chafin[25] had begun to set up defenses on Blair Mountain. He was supported financially by the Logan County Coal Operators Association, creating the nation's largest private armed force of nearly 2,000.

The first skirmishes occurred on the morning of August 25. The bulk of the miners were still 15 mi (24 km) away. The following day, President Warren Harding threatened to send in federal troops and Army Martin MB-1 bombers. After a long meeting in Madison, the seat of Boone County, the miners were convinced to return home. But the struggle was far from over. After spending days assembling his private army, Chafin would not be denied his battle to end union attempts at organizing Logan County coal mines. Within hours of the Madison decision, rumors abounded that Chafin's men had shot union sympathizers in the town of Sharples, just north of Blair Mountain – and that families had been caught in crossfire during the skirmishes. Infuriated, the miners turned back toward Blair Mountain, many traveling in other stolen and commandeered trains.

By August 29 battle was fully joined. Chafin's men, though outnumbered, had the advantage of higher positions and better weaponry. Private planes were hired to drop homemade bombs on the miners. A combination of gas and explosive bombs left over from World War I were dropped in several locations near the towns of Jeffery, Sharples and Blair. At least one did not explode and was recovered by the miners; it was used months later to great effect as evidence for the defense during treason and murder trials. On orders from General Billy Mitchell, Army bombers from Maryland were also used for aerial surveillance. One Martin bomber crashed on its return flight, killing the three crew members.[26][2]

On August 30, Morgan appointed Colonel William Eubanks of the West Virginia National Guard to command the government and volunteer forces confronting the miners.[27] Sporadic gun battles continued for a week, with the miners at one time nearly breaking through to the town of Logan and their target destinations, the non-unionized counties to the south, Logan and Mingo. Up to 30 deaths were reported by Chafin's side and 50–100 on the union miners' side, with hundreds more injured or wounded. Chafin's forces consisted of 90 men from Bluefield, West Virginia; 40 from Huntington, West Virginia; and about 120 from the West Virginia State Police.[28] Three of Chafin's forces, two volunteers and a deputy sheriff, were killed[29][30][31][32] and one miner was fatally wounded.[33]

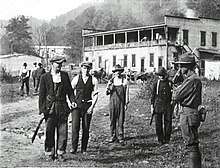

Federal troops arrived by September 2. Realizing he would lose a lot of good miners if the battle continued with the military, Bill Blizzard passed the word for the miners to start heading home the following day. Miners fearing jail and confiscation of their guns found clever ways to hide rifles and handguns in the woods before leaving Logan County. Collectors and researchers are still finding weapons and ammunition embedded in old trees and in rock crevices. Thousands of spent and live cartridges have made it into private collections.

After the battle, 985 miners were indicted for murder, conspiracy to commit murder, accessory to murder, and treason against the state of West Virginia.[34] Though some were acquitted by sympathetic juries, others were imprisoned for years. The last was paroled in 1925. At Blizzard's trial, the unexploded bomb was used as evidence of the government and companies' brutality, and he was acquitted[27].

Legacy

In the short term the battle was an overwhelming victory for coal industry owners and management. UMW membership plummeted from more than 50,000 miners to approximately 10,000 over the next several years, and it was not until 1935 – following the Great Depression and the beginning of the New Deal under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt – that the UMW fully organized in southern West Virginia.

This union defeat had major implications for the UMWA as a whole. After World War I, as the coal industry began to collapse, union mining was no longer financially sustainable. Because of the defeat in West Virginia, the union was undermined in Pennsylvania and Kentucky also. By the end of 1925 Illinois was the only remaining unionized state that could compete, in terms of soft coal production, with the others listed.

In the long term, the battle raised awareness of the appalling conditions miners faced in the dangerous West Virginia coalfields, and led directly to a change in union tactics in political battles to get the law on labor's side via confrontations with recalcitrant and abusive managements and thence to the much larger organized labor victory a few years later during the New Deal in 1933. That in turn led to the UMWA helping organize many better-known unions, such as the Steel Workers during the mid-'30s.

In the final analysis, management's success was a Pyrrhic victory that helped lead to a much larger and stronger organized labor movement in many other industries and labor union affiliations and umbrella organizations, such as the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

Future of site

Starting in the summer of 2006 a local hobby archeologist, Kenneth King, led a team of professional archeologists to further investigate the battlefield. King and the team's initial survey "mapped 15 combat sites and discovered more than a thousand artifacts, from rifle and shotgun shell casings to coins and batteries [and] little sign of disturbance" to the site, challenging earlier surveys conducted by Arch. In April 2008, Blair Mountain was chosen for the list of protected places on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).

The site was accepted, and added to the NRHP list on March 30, 2009, although clerical errors by the West Virginia State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) failed to notarize all objections.[35] In mid-2010, "Subsidiaries of two of the United States' largest coal producers – Arch Coal, Inc., and Massey Energy Company, ... – hold permits to blast and strip-mine huge chunks of the upper slopes and ridge of Blair Mountain, removing much of the mountaintop", National Geographic reported.[36]

In October 2012 a federal district judge ruled that a coalition of preservation groups did not have standing to sue to protect the historic site.[37] On August 26, 2014, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit voted 2–1 to overturn the ruling and returned the case.[38]

In April 2016 the order to remove the Blair Mountain battlefield from the National Register was overturned by a federal court, and the further decision to add the site back to the register was turned over to the Keeper of the National Register. On June 27, 2018, the Keeper's Office decided that the 2009 decision to remove the site from its listings was "erroneous" and issued a statement confirming that as of that date the site was again on the National Register.[39][40]

In fiction

The Blair Mountain march, as well as the events leading up to it and those immediately following it, are depicted in the novels Storming Heaven (Denise Giardina, 1987), Blair Mountain (Jonathan Lynn, 2006), and Carla Rising (Topper Sherwood, 2015).[41] In The Ballad of Trenchmouth Taggart (Glenn Taylor, 2008) the book's main character meets Sid Hatfield, and is involved in the Matewan massacre and the ensuing battle. John Sayles' 1987 film Matewan depicts the Matewan Massacre, a small part of the Blair Mountain story. Diane Gilliam Fisher's poetry collection Kettle Bottom also focuses on the events of the Battle of Blair Mountain, from the perspective of the miners' families.

In music

Tom Breiding's "Union Miner" from "The Unbroken Circle: Songs of the West Virginia Coalfields" (2008) accurately depicts events surrounding the Battle of Blair Mountain from the perspective of a coal miner preparing to march. "Union Miner" can be heard at virtually every event sponsored by the United Mine Workers of America today. Tom Breiding has provided the music for the UMWA's "Fairness at Patriot" campaign (2013–14), the UMWA centennial commemoration of the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado (2014), the inauguration of UMWA officers (2014), and various other Mine Workers events.

"Miners' Rebellion" (2012) by alt country band The Miners tells the story of the Battle of Blair Mountain. The song is contained on The Miners debut EP also entitled Miners' Rebellion.

When Miners March (2007) contains 16 recently written songs (not music from the 1920s) from the audiobook When Miners March – The Battle of Blair Mountain.

"Battle of Blair Mountain" (2004) is a song by folk singer David Rovics and can be found on his album Songs for Mahmud.

The song "Battle of Blair Mountain" (2010) written by Louise Mosrie and Mike Richardson can be found on Louise Mosrie's album Home (Zoe Cat Music/BMI).

The song "Red Neck War" by Byzantine is based on the Battle of Blair Mountain and can be found on the group's 2005 album ... And They Shall Take Up Serpents (Prosthetic Records). The song "Black Lung" by The Radio Nationals (band) is also based on this conflict.

Blair Pathways (2011) is a multimedia project, including a CD and maps, tracing the history of the Blair Mountain area and its labor disputes. It contains music by a number of traditional artists, including Riley Baugus and Tim Eriksen.

Chicago Irish folk punk band The Fisticuffs released a song titled "The Ballad of Bill Blizzard" on their 2011 final album You'll Not Take Us Alive about the battle of Blair Mountain.

Historic interpretation

The Battle of Blair Mountain is interpreted by the state of West Virginia through a Historic Highway marker. The marker was made by the West Virginia Division of Culture and History. The marker reads,

BATTLE OF BLAIR MT. In August of 1921, 7000 striking miners led by Bill Blizzard met at Marmet for a march on Logan to organize the southern coalfields for the UMWA. Reaching Blair Mt. on August 31, they were repelled by deputies and mine guards, under Sheriff Don Chafin, waiting in fortified positions. The five day battle ended with the arrival of U.S. Army and Air Corps. UMWA organizing efforts in southern WV were halted until 1933.

The marker is on West Virginia 17, about eight miles (13 km) east of Logan, between Ethel and Blair.[42]

See also

- Anti-union violence in the United States

- Copper Country strike of 1913–1914

- Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894

- Colorado Labor Wars

- Coal strike of 1902

- Harlan County War

- Illinois coal wars

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- Labor history of the United States

- Ludlow Massacre

- Mining in the United States

- Molly Maguires

- Railroad Wars

- Sheep Wars

- Union violence in the United States

- West Virginia Coal Wars

Citations

- Laurie, Clayton D. (1991). "The United States Army and the Return to Normalcy in Labor Dispute Interventions: The Case of the West Virginia Coal Mine Wars, 1920–1921". West Virginia History. West Virginia Archives and History. 50: 1–24. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Torok 2004, p. 48.

- Kinder 2005, p. 149.

- Patel 2012.

- Ayers, Rothrock and King 2007

- Proclamation 1606, August 30, 1921

- Savage 1990, p. 16.

- Savage 1990, pp. 20–22.

- Savage 1990, p. 21.

- Savage 1990, p. 26.

- Savage 1990, p. 28.

- Savage 1990, p. 60.

- Savage 1990, p. 50.

- Shogan 2004, p. 98.

- Shogan 2004, p. 81.

- Savage 1990, p. 53.

- Savage 1990, p. 57.

- Savage 1990, p. 58.

- Shogan 2004, pp. 154–156.

- Shogan 2004, pp. 157–158.

- Savage 1990, p. 73.

- Savage 1990, p. 75.

- Shogan 2004, pp. 164–165.

- Shogan 2004, p. 166.

- The Herald-Dispatch: Funeral Rites Thursday For Colorful Don Chafin. August 10, 1954

- Laurie, Clayton D. (1991). "The United States Army and the Return to Normalcy in Labor Dispute Interventions: The Case of the West Virginia Coal Mine Wars, 1920–1921". West Virginia History. West Virginia Archives and History. 50: 1–24. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- The Battle of Blair Mountain: The Story of America's Largest Labor Uprising By Robert Shogan

- West Virginia Coal Fields: Hearings Before the Committee on Education and ...." p. 995 Testimony of Arnold Jackson, Superintedant of the West Virginia State Police testimony

- Gettysburg Times September 1, 1921

- Odmp memorial John Gore

- From 1920 to 1921 3 members of the West Virginia State Police were also killed

- West Virginia Coal Fields: Hearings Before the Committee on Education and ...". p. 996 testimony of Jackson Arnold Superintendent of the West Virginia State Police that he knew of two dead men at Blair Mountain and that a third man had been found dead in the woods at Blair Mountain

- Schenectady Gazette June 19, 1922

- "National Coal Heritage Area/ Coal Heritage Trail". www.coalheritage.org. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- "Division News... Blair Mountain information". wvculture.org. West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- Pringle, Heather, "Coal Firms to Strip-Mine Historic Battlefield?", National Geographic, June 2, 2010. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- Ward, Ken (Oct 2, 2012). "Judge Rules Against Groups in Blair Mountain List Case". Coal Tattoo. West Virginia Gazette. Retrieved Sep 15, 2013.

- Nyden, Paul J. "Federal appeals court says groups can sue over Blair Mountain". wvgazette.com. The Charleston Gazette. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- "Decision Memorandum Regarding the 2009 Decision Removing the Blair Mountain Battlefield from the National Register of Historic Places". June 27, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- Mishkin, Kate (June 29, 2018). "Blair Mountain Battlefield back on National Register of Historic Places". Charlotte Gazette-Mail. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- Imbrogno, Douglas (July 19, 2015). "Novel 'Carla Rising' animated by the Battle of Blair Mountain". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- State of West Virginia (2002). Marking Our Past: West Virginia's Historical Highway Markers. Charleston: West Virginia Division of Culture and History. p. 83.

General references

- Blizzard, William C. (2005). When Miners March. Gay, WV: Appalachian Community Press. ISBN 978-0-9764706-0-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Corbin, David (2011). Gun Thugs, Rednecks, and Radicals: A Documentary History of the West Virginia Mine Wars. Oakland: PM Press. ISBN 9781604864526.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Corbin, David, ed. (1998). The West Virginia Mine Wars: An Anthology. Martinsburg, WV: Appalachian Editions. ISBN 978-0-9627486-0-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kinder, Chuck (2005). Last Mountain Dancer: Hard-Earned Lessons in Love, Loss, and Honky-Tonk. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-7867-1653-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Howard B. (1969). Bloodletting in Appalachia: The Story of West Virginia's Four Major Mine Wars and Other Thrilling Incidents of Its Coal Fields. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press. ISBN 978-0-87012-041-1.

bloodletting in Appalachia.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - McGuire, Randall; Reckner, Paul (2003). "Building a Working-Class Archaeology: The Colorado Coal Field War Project". Industrial Archaeology Review. 25 (2): 83–95. doi:10.1179/iar.2003.25.2.83.

- Mooney, Fred (1967). Struggle in the coal fields: The Autobiography of Fred Mooney. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Library. OCLC 795742.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patel, Samir S. (January–February 2012). "Mountaintop Rescue". Archaeology. 65 (1). Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Savage, Lon (1990). Thunder in the Mountains: The West Virginia Mine War, 1920–21. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-3634-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shogan, Robert (2004). The Battle of Blair Mountain: The Story of America's Largest Union Uprising. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4096-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- State of West Virginia (2002). Marking Our Past: West Virgnia's Historical Highway Markers. Charleston: West Virginia Division of Culture and History.

- Torok, George D. (2004). A guide to historic coal towns of the Big Sandy River Valley. knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-282-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- HistoryPodcast and transcription: "The Battle of Blair Mountain" Accessed January 13, 2008

- Official Matewan, WV Tourism Website at VisitMatewan.com

- Blair Mountain Heritage Alliance to help preservation efforts for the Blair Mountain battlefield and the community of Blair, WV

- West Virginia Mine Wars Museum independent history museum covering the Mine Wars Era in Matewan, WV.

- Baseball and rebellion: The treason trial of Bill Blizzard Appalachian Voice, Spring 2008.

- The Battle for Blair Mountain (2010) for information on past and present conflicts at Blair Mountain

- Zinn Education Guide: Teaching Guide for Blair Mountain

- '"A Moment in the Sun": An Extended Interview with Independent Filmmaker, Author John Sayles', Democracy Now, June 17 & November 24, 2011 air-dates; audio download and transcript. Includes discussion of Matewan, Sayles' film about an aspect of the 1920s Blair Mountain conflict; also discussion of "second battle" in the 21st century

- The Blair Pathways Project

- "Detective Tells Story of Fatal Matewan Riot". New-York Tribune. February 13, 1921. Retrieved 24 November 2012.