Nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of being harmless to one's self and others under every condition. It comes from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it also refers to a general philosophy of abstention from violence. This may be based on moral, religious or spiritual principles, or the reasons for it may be purely strategic or pragmatic.[1]

Nonviolence has "active" or "activist" elements, in that believers generally accept the need for nonviolence as a means to achieve political and social change. Thus, for example, Tolstoyan and Gandhian non violence is both a philosophy and strategy for social change that rejects the use of violence, but at the same time it sees nonviolent action (also called civil resistance) as an alternative to passive acceptance of oppression or armed struggle against it. In general, advocates of an activist philosophy of nonviolence use diverse methods in their campaigns for social change, including critical forms of education and persuasion, mass noncooperation, civil disobedience, nonviolent direct action, and social, political, cultural and economic forms of intervention.

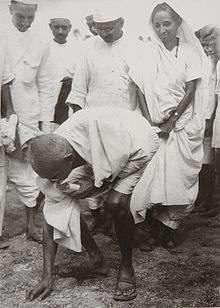

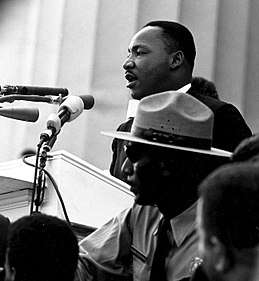

In modern times, nonviolent methods have been a powerful tool for social protest and revolutionary social and political change.[2][3][4] There are many examples of their use. Fuller surveys may be found in the entries on civil resistance, nonviolent resistance and nonviolent revolution. Here certain movements which were particularly influenced by a philosophy of nonviolence should be mentioned, including Mahatma Gandhi leadership of a successful decades-long nonviolent struggle against British rule in India, Martin Luther King's and James Bevel's adoption of Gandhi's nonviolent methods in their campaigns to win civil rights for African Americans,[5][6] and César Chávez's campaigns of nonviolence in the 1960s to protest the treatment of farm workers in California.[7] In August, 1968, Czechoslovakia's non-violent defense against the Soviet occupation prevented the occupier from achieving their objectives. The 1989 "Velvet Revolution" in Czechoslovakia that saw the overthrow of the Communist government[8] is considered one of the most important of the largely nonviolent Revolutions of 1989.[9] Most recently the nonviolent campaigns of Leymah Gbowee and the women of Liberia were able to achieve peace after a 14-year civil war.[10] This story is captured in a 2008 documentary film Pray the Devil Back to Hell.

The term "nonviolence" is often linked with peace or it is used as a synonym for it, and despite the fact that it is frequently equated with passivity and pacifism, this equation is rejected by nonviolent advocates and activists.[11] Nonviolence specifically refers to the absence of violence and it is always the choice to do no harm or the choice to do the least amount of harm, and passivity is the choice to do nothing. Sometimes nonviolence is passive, and other times it isn't. For example, if a house is burning down with mice or insects in it, the most harmless appropriate action is to put the fire out, not to sit by and passively let the fire burn. At times there is confusion and contradiction about nonviolence, harmlessness and passivity. A confused person may advocate nonviolence in a specific context while advocating violence in other contexts. For example, someone who passionately opposes abortion or meat eating may concurrently advocate violence to kill an abortionist or attack a slaughterhouse, which makes that person a violent person.[12]

"Nonviolence is a powerful and just weapon. Indeed, it is a weapon unique in history, which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it."

— Martin Luther King, Jr., The Quest for Peace and Justice (1964) Martin Luther King's Nobel Lecture, delivered in the Auditorium of the University of Oslo at December 11, 1964

Mahatma Gandhi was of the view:

No religion in the World has explained the principle of Ahimsa so deeply and systematically as is discussed with its applicability in every human life in Jainism. As and when the benevolent principle of Ahimsa or non-violence will be ascribed for practice by the people of the world to achieve their end of life in this world and beyond. Jainism is sure to have the uppermost status and Lord Mahavira is sure to be respected as the greatest authority on Ahimsa.[13]

Bal Gangadhar Tilak has credited Jainism with the cessation of slaughter of animals in the brahamanical religion. Some scholars have traced the origin of Ahimsa to Jains and their precursor, the sramanas. According to Thomas McEvilley, a noted Indologist, certain seals of the Indus Valley civilisation depict a meditative figure who is surrounded by a multitude of wild animals, providing evidence of the proto yoga tradition in India which is akin to Jainism. This particular image might suggest that all of the animals which are depicted in it are sacred to this particular practitioner. Consequently, these animals would be protected from harm.

Origins

Nonviolence or Ahimsa is one of the cardinal virtues[14] and an important tenet of Jainism, Hinduism and Buddhism. It is a multidimensional concept,[15] inspired by the premise that all living beings have the spark of the divine spiritual energy; therefore, to hurt another being is to hurt oneself. It has also been related to the notion that any violence has karmic consequences. While ancient scholars of Hinduism pioneered and over time perfected the principles of Ahimsa, the concept reached an extraordinary status in the ethical philosophy of Jainism.[14][16]

According to Jain mythology, the first tirthankara, Rushabhdev, originated the idea of nonviolence over a million years ago.[17] Historically, Parsvanatha, the twenty-third tirthankara of Jainism, advocated for and preached the concept of nonviolence in around the 8th century BC.[18] Mahavira, the twenty-fourth and last tirthankara, then further strengthened the idea in the 6th century BC.[19]

Forms

Advocates of nonviolent action believe cooperation and consent are the roots of civil or political power: all regimes, including bureaucratic institutions, financial institutions, and the armed segments of society (such as the military and police); depend on compliance from citizens.[20] On a national level, the strategy of nonviolent action seeks to undermine the power of rulers by encouraging people to withdraw their consent and cooperation. The forms of nonviolence draw inspiration from both religious or ethical beliefs and political analysis. Religious or ethically based nonviolence is sometimes referred to as principled, philosophical, or ethical nonviolence, while nonviolence based on political analysis is often referred to as tactical, strategic, or pragmatic nonviolent action. Commonly, both of these dimensions may be present within the thinking of particular movements or individuals.[21]

Pragmatic

The fundamental concept of pragmatic (tactical or strategic) nonviolent action is to create a social dynamic or political movement that can create a national or international dialogue which effects social change without necessarily winning over those who wish to maintain the status quo.[22]

Nicolas Walter noted the idea that nonviolence might work "runs under the surface of Western political thought without ever quite disappearing".[23] Walter noted Étienne de La Boétie's Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (sixteenth century) and P.B. Shelley's The Masque of Anarchy (1819) contain arguments for resisting tyranny without using violence.[23] In 1838, William Lloyd Garrison helped found the New England Non-Resistance Society, a society devoted to achieving racial and gender equality through the rejection of all violent actions.[23]

In modern industrial democracies, nonviolent action has been used extensively by political sectors without mainstream political power such as labor, peace, environment and women's movements. Lesser known is the role that nonviolent action has played and continues to play in undermining the power of repressive political regimes in the developing world and the former eastern bloc. Susan Ives emphasizes this point by quoting Walter Wink:

"In 1989, thirteen nations comprising 1,695,000,000 people experienced nonviolent revolutions that succeeded beyond anyone's wildest expectations ... If we add all the countries touched by major nonviolent actions in our century (the Philippines, South Africa ... the independence movement in India ...), the figure reaches 3,337,400,000, a staggering 65% of humanity! All this in the teeth of the assertion, endlessly repeated, that nonviolence doesn't work in the 'real' world."

— Walter Wink, Christian theologian[9]

As a technique for social struggle, nonviolent action has been described as "the politics of ordinary people", reflecting its historically mass-based use by populations throughout the world and history.

Movements most often associated with nonviolence are the non-cooperation campaign for Indian independence led by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, and the People Power Revolution in the Philippines.

Also of primary significance is the notion that just means are the most likely to lead to just ends. When Gandhi said that "the means may be likened to the seed, the end to a tree," he expressed the philosophical kernel of what some refer to as prefigurative politics. Martin Luther King, a student of Gandhian nonviolent resistance, concurred with this tenet, concluding that "nonviolence demands that the means we use must be as pure as the ends we seek." Proponents of nonviolence reason that the actions taken in the present inevitably re-shape the social order in like form. They would argue, for instance, that it is fundamentally irrational to use violence to achieve a peaceful society.

Respect or love for opponents also has a pragmatic justification, in that the technique of separating the deeds from the doers allows for the possibility of the doers changing their behaviour, and perhaps their beliefs. Martin Luther King wrote, "Nonviolent resistance... avoids not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit. The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent, but he also refuses to hate him."[24]

Finally, the notion of Satya, or Truth, is central to the Gandhian conception of nonviolence. Gandhi saw Truth as something that is multifaceted and unable to be grasped in its entirety by any one individual. All carry pieces of the Truth, he believed, but all need the pieces of others’ truths in order to pursue the greater Truth. This led him to believe in the inherent worth of dialogue with opponents, in order to understand motivations. On a practical level, the willingness to listen to another's point of view is largely dependent on reciprocity. In order to be heard by one's opponents, one must also be prepared to listen.

Nonviolence has obtained a level of institutional recognition and endorsement at the global level. On November 10, 1998, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the first decade of the 21st century and the third millennium, the years 2001 to 2010, as the International Decade for the Promotion of a Culture of Peace and Non-Violence for the Children of the World.

Ethical

For many, practicing nonviolence goes deeper than abstaining from violent behavior or words. It means overriding the impulse to be hateful and holding love for everyone, even those with whom one strongly disagrees. In this view, because violence is learned, it is necessary to unlearn violence by practicing love and compassion at every possible opportunity. For some, the commitment to non-violence entails a belief in restorative or transformative justice, an abolition of the death penalty and other harsh punishments. This may involve the necessity of caring for those who are violent.

Nonviolence, for many, involves a respect and reverence for all sentient, and perhaps even non-sentient, beings. This might include abolitionism against animals as property, the practice of not eating animal products or by-products (vegetarianism or veganism), spiritual practices of non-harm to all beings, and caring for the rights of all beings. Mohandas Gandhi, James Bevel, and other nonviolent proponents advocated vegetarianism as part of their nonviolent philosophy. Buddhists extend this respect for life to animals, plants, and even minerals, while Jainism extend this respect for life to animals, plants and even small organisms such as insects.[25][26]

The classical Indian text of Tirukkuṛaḷ deals with the ethics of non-violence or non-harming through verses 311–320 in Chapter 32 of Book 1,[27] further discussing compassion in Chapter 25 (verses 241-250), moral vegetarianism or veganism in Chapter 26 (verses 251-260), and non-killing in Chapter 33 (verses 321-330).[28]

Semai people

The Semai ethnic group living in the center of the Malay Peninsula in Southeast Asia are known for their nonviolence.[29] The Semai punan ethical or religious principle[30] strongly pressures members of the culture towards nonviolent, non-coercive, and non-competitive behaviour. It has been suggested that the Semai's non-violence is a response to historic threats from slaving states; as the Semai were constantly defeated by slavers and Malaysian immigrants, they preferred to flee rather than fight and thus evolved into a general norm of non-violence.[31] This does not mean the Semai are incapable of violence however; during the Malayan Emergency, the British recruited some Semai to fight against communist insurgents and according to Robert Knox Dentan the Semai believe that as Malaysia industrialises, it will be harder for the Semai to use their strategy of fleeing and they will have to fight instead.[32][33]

Religious

Hinduism

Ancient Vedic texts

Ahimsa as an ethical concept evolved in Vedic texts.[16][34] The oldest scripts, along with discussing ritual animal sacrifices, indirectly mention Ahimsa, but do not emphasise it. Over time, the Hindu scripts revise ritual practices and the concept of Ahimsa is increasingly refined and emphasised, ultimately Ahimsa becomes the highest virtue by the late Vedic era (about 500 BC). For example, hymn 10.22.25 in the Rig Veda uses the words Satya (truthfulness) and Ahimsa in a prayer to deity Indra;[35] later, the Yajur Veda dated to be between 1000 BC and 600 BC, states, "may all beings look at me with a friendly eye, may I do likewise, and may we look at each other with the eyes of a friend".[16][36]

The term Ahimsa appears in the text Taittiriya Shakha of the Yajurveda (TS 5.2.8.7), where it refers to non-injury to the sacrificer himself.[37] It occurs several times in the Shatapatha Brahmana in the sense of "non-injury".[38] The Ahimsa doctrine is a late Vedic era development in Brahmanical culture.[39] The earliest reference to the idea of non-violence to animals ("pashu-Ahimsa"), apparently in a moral sense, is in the Kapisthala Katha Samhita of the Yajurveda (KapS 31.11), which may have been written in about the 8th century BCE.[40]

Bowker states the word appears but is uncommon in the principal Upanishads.[41] Kaneda gives examples of the word Ahimsa in these Upanishads.[42] Other scholars[15][43] suggest Ahimsa as an ethical concept that started evolving in the Vedas, becoming an increasingly central concept in Upanishads.

The Chāndogya Upaniṣad, dated to the 8th or 7th century BCE, one of the oldest Upanishads, has the earliest evidence for the Vedic era use of the word Ahimsa in the sense familiar in Hinduism (a code of conduct). It bars violence against "all creatures" (sarvabhuta) and the practitioner of Ahimsa is said to escape from the cycle of rebirths (CU 8.15.1).[44] Some scholars state that this 8th or 7th-century BCE mention may have been an influence of Jainism on Vedic Hinduism.[45] Others scholar state that this relationship is speculative, and though Jainism is an ancient tradition the oldest traceable texts of Jainism tradition are from many centuries after the Vedic era ended.[46][47]

Chāndogya Upaniṣad also names Ahimsa, along with Satyavacanam (truthfulness), Arjavam (sincerity), Danam (charity), Tapo (penance/meditation), as one of five essential virtues (CU 3.17.4).[15][48]

The Sandilya Upanishad lists ten forbearances: Ahimsa, Satya, Asteya, Brahmacharya, Daya, Arjava, Kshama, Dhriti, Mitahara and Saucha.[49][50] According to Kaneda,[42] the term Ahimsa is an important spiritual doctrine shared by Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. It literally means 'non-injury' and 'non-killing'. It implies the total avoidance of harming of any kind of living creatures not only by deeds, but also by words and in thoughts.

The Epics

The Mahabharata, one of the epics of Hinduism, has multiple mentions of the phrase Ahimsa Paramo Dharma (अहिंसा परमॊ धर्मः), which literally means: non-violence is the highest moral virtue. For example, Mahaprasthanika Parva has the verse:[51]

अहिंसा परमॊ धर्मस तथाहिंसा परॊ दमः।

अहिंसा परमं दानम अहिंसा परमस तपः।

अहिंसा परमॊ यज्ञस तथाहिस्मा परं बलम।

अहिंसा परमं मित्रम अहिंसा परमं सुखम।

अहिंसा परमं सत्यम अहिंसा परमं शरुतम॥

The above passage from Mahabharata emphasises the cardinal importance of Ahimsa in Hinduism, and literally means: Ahimsa is the highest virtue, Ahimsa is the highest self-control, Ahimsa is the greatest gift, Ahimsa is the best suffering, Ahimsa is the highest sacrifice, Ahimsa is the finest strength, Ahimsa is the greatest friend, Ahimsa is the greatest happiness, Ahimsa is the highest truth, and Ahimsa is the greatest teaching.[52][53] Some other examples where the phrase Ahimsa Paramo Dharma are discussed include Adi Parva, Vana Parva and Anushasana Parva. The Bhagavad Gita, among other things, discusses the doubts and questions about appropriate response when one faces systematic violence or war. These verses develop the concepts of lawful violence in self-defence and the theories of just war. However, there is no consensus on this interpretation. Gandhi, for example, considers this debate about non-violence and lawful violence as a mere metaphor for the internal war within each human being, when he or she faces moral questions.[54]

Self-defence, criminal law, and war

The classical texts of Hinduism devote numerous chapters discussing what people who practice the virtue of Ahimsa, can and must do when they are faced with war, violent threat or need to sentence someone convicted of a crime. These discussions have led to theories of just war, theories of reasonable self-defence and theories of proportionate punishment.[55][56] Arthashastra discusses, among other things, why and what constitutes proportionate response and punishment.[57][58]

- War

The precepts of Ahimsa under Hinduism require that war must be avoided, with sincere and truthful dialogue. Force must be the last resort. If war becomes necessary, its cause must be just, its purpose virtuous, its objective to restrain the wicked, its aim peace, its method lawful.[55][57] War can only be started and stopped by a legitimate authority. Weapons used must be proportionate to the opponent and the aim of war, not indiscriminate tools of destruction.[59] All strategies and weapons used in the war must be to defeat the opponent, not designed to cause misery to the opponent; for example, use of arrows is allowed, but use of arrows smeared with painful poison is not allowed. Warriors must use judgment in the battlefield. Cruelty to the opponent during war is forbidden. Wounded, unarmed opponent warriors must not be attacked or killed, they must be brought to your realm and given medical treatment.[57] Children, women and civilians must not be injured. While the war is in progress, sincere dialogue for peace must continue.[55][56]

- Self-defence

In matters of self-defence, different interpretations of ancient Hindu texts have been offered. For example, Tähtinen suggests self-defence is appropriate, criminals are not protected by the rule of Ahimsa, and Hindu scriptures support the use of violence against an armed attacker.[60][61] Ahimsa is not meant to imply pacifism.[62]

Alternate theories of self-defence, inspired by Ahimsa, build principles similar to theories of just war. Aikido, pioneered in Japan, illustrates one such principles of self-defence. Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido, described his inspiration as Ahimsa.[63] According to this interpretation of Ahimsa in self-defence, one must not assume that the world is free of aggression. One must presume that some people will, out of ignorance, error or fear, attack other persons or intrude into their space, physically or verbally. The aim of self-defence, suggested Ueshiba, must be to neutralise the aggression of the attacker, and avoid the conflict. The best defence is one where the victim is protected, as well as the attacker is respected and not injured if possible. Under Ahimsa and Aikido, there are no enemies, and appropriate self-defence focuses on neutralising the immaturity, assumptions and aggressive strivings of the attacker.[64][65]

- Criminal law

Tähtinen concludes that Hindus have no misgivings about death penalty; their position is that evil-doers who deserve death should be killed, and that a king in particular is obliged to punish criminals and should not hesitate to kill them, even if they happen to be his own brothers and sons.[66]

Other scholars[56][57] conclude that the scriptures of Hinduism suggest sentences for any crime must be fair, proportional and not cruel.

Non-human life

The Hindu precept of 'cause no injury' applies to animals and all life forms. This precept isn't found in the oldest verses of Vedas, but increasingly becomes one of the central ideas between 500 BC and 400 AD.[67][68] In the oldest texts, numerous ritual sacrifices of animals, including cows and horses, are highlighted and hardly any mention is made of Ahimsa to non-human life.[69][70]

Hindu scriptures, dated to between 5th century and 1st century BC, while discussing human diet, initially suggest kosher meat may be eaten, evolving it with the suggestion that only meat obtained through ritual sacrifice can be eaten, then that one should eat no meat because it hurts animals, with verses describing the noble life as one that lives on flowers, roots and fruits alone.[67][71]

Later texts of Hinduism declare Ahimsa one of the primary virtues, declare any killing or harming any life as against dharma (moral life). Finally, the discussion in Upanishads and Hindu Epics[72] shifts to whether a human being can ever live his or her life without harming animal and plant life in some way; which and when plants or animal meat may be eaten, whether violence against animals causes human beings to become less compassionate, and if and how one may exert least harm to non-human life consistent with ahimsa precept, given the constraints of life and human needs.[73][74] The Mahabharata permits hunting by warriors, but opposes it in the case of hermits who must be strictly non-violent. Sushruta Samhita, a Hindu text written in the 3rd or 4th century, in Chapter XLVI suggests proper diet as a means of treating certain illnesses, and recommends various fishes and meats for different ailments and for pregnant women,[75][76] and the Charaka Samhita describes meat as superior to all other kinds of food for convalescents.[77]

Across the texts of Hinduism, there is a profusion of ideas about the virtue of Ahimsa when applied to non-human life, but without a universal consensus.[78] Alsdorf claims the debate and disagreements between supporters of vegetarian lifestyle and meat eaters was significant. Even suggested exceptions – ritual slaughter and hunting – were challenged by advocates of Ahimsa.[79][80][81] In the Mahabharata both sides present various arguments to substantiate their viewpoints. Moreover, a hunter defends his profession in a long discourse.[82]

Many of the arguments proposed in favor of non-violence to animals refer to the bliss one feels, the rewards it entails before or after death, the danger and harm it prevents, as well as to the karmic consequences of violence.[83][84]

The ancient Hindu texts discuss Ahimsa and non-animal life. They discourage wanton destruction of nature including of wild and cultivated plants. Hermits (sannyasins) were urged to live on a fruitarian diet so as to avoid the destruction of plants.[85][86] Scholars[87][88] claim the principles of ecological non-violence is innate in the Hindu tradition, and its conceptual fountain has been Ahimsa as their cardinal virtue.

The classical literature of Hinduism exists in many Indian languages. For example, Tirukkuṛaḷ, written between 200 BC and 400 AD, and sometimes called the Tamil Veda, is one of the most cherished classics written in a South Indian language. Tirukkuṛaḷ dedicates Chapters 26, 32 and 33 of Book 1 to the virtue of Ahimsa, namely, moral vegetarianism, non-harming, and non-killing, respectively. Tirukkuṛaḷ says that Ahimsa applies to all life forms.[89][90][91]

Jainism

In Jainism, the understanding and implementation of Ahimsā is more radical, scrupulous, and comprehensive than in any other religion.[92] Killing any living being out of passions is considered hiṃsā (to injure) and abstaining from such an act is ahimsā (noninjury).[93] The vow of ahimsā is considered the foremost among the 'five vows of Jainism'. Other vows like truth (Satya) are meant for safeguarding the vow of ahimsā.[94] In the practice of Ahimsa, the requirements are less strict for the lay persons (sravakas) who have undertaken anuvrata (Smaller Vows) than for the Jain monastics who are bound by the Mahavrata "Great Vows".[95] The statement ahimsā paramo dharmaḥ is often found inscribed on the walls of the Jain temples.[96] Like in Hinduism, the aim is to prevent the accumulation of harmful karma.[97] When lord Mahaviraswami revived and reorganized the Jain faith in the 6th or 5th century BCE,[98] Rishabhanatha (Ādinātha), the first Jain Tirthankara, whom modern Western historians consider to be a historical figure, followed by Parshvanatha (Pārśvanātha)[99] the twenty-third Tirthankara lived in about the 8th century BCE.[100] He founded the community to which Mahavira's parents belonged.[101] Ahimsa was already part of the "Fourfold Restraint" (Caujjama), the vows taken by Parshva's followers.[102] In the times of Mahavira and in the following centuries, Jains were at odds with both Buddhists and followers of the Vedic religion or Hindus, whom they accused of negligence and inconsistency in the implementation of Ahimsa.[103] According to the Jain tradition either lacto vegetarianism or veganism is mandatory.[104]

The Jain concept of Ahimsa is characterised by several aspects. It does not make any exception for ritual sacrificers and professional warrior-hunters. Killing of animals for food is absolutely ruled out.[105] Jains also make considerable efforts not to injure plants in everyday life as far as possible. Though they admit that plants must be destroyed for the sake of food, they accept such violence only inasmuch as it is indispensable for human survival, and there are special instructions for preventing unnecessary violence against plants.[106] Jains go out of their way so as not to hurt even small insects and other minuscule animals.[107] For example, Jains often do not go out at night, when they are more likely to step upon an insect. In their view, injury caused by carelessness is like injury caused by deliberate action.[108] Eating honey is strictly outlawed, as it would amount to violence against the bees.[109] Some Jains abstain from farming because it inevitably entails unintentional killing or injuring of many small animals, such as worms and insects,[110] but agriculture is not forbidden in general and there are Jain farmers.[111]

Theoretically, all life forms are said to deserve full protection from all kinds of injury, but Jains recognise a hierarchy of life. Mobile beings are given higher protection than immobile ones. For the mobile beings, they distinguish between one-sensed, two-sensed, three-sensed, four-sensed and five-sensed ones; a one-sensed animal has touch as its only sensory modality. The more senses a being has, the more they care about non-injuring it. Among the five-sensed beings, the precept of non-injury and non-violence to the rational ones (humans) is strongest in Jain Ahimsa.[112]

Jains agree with Hindus that violence in self-defence can be justified,[113] and they agree that a soldier who kills enemies in combat is performing a legitimate duty.[114] Jain communities accepted the use of military power for their defence, there were Jain monarchs, military commanders, and soldiers.[115]

Buddhism

In Buddhist texts Ahimsa (or its Pāli cognate avihiṃsā) is part of the Five Precepts (Pañcasīla), the first of which has been to abstain from killing. This precept of Ahimsa is applicable to both the Buddhist layperson and the monk community.[116][117][118]

The Ahimsa precept is not a commandment and transgressions did not invite religious sanctions for layperson, but their power has been in the Buddhist belief in karmic consequences and their impact in afterlife during rebirth.[119] Killing, in Buddhist belief, could lead to rebirth in the hellish realm, and for a longer time in more severe conditions if the murder victim was a monk.[119] Saving animals from slaughter for meat, is believed to be a way to acquire merit for better rebirth. These moral precepts have been voluntarily self-enforced in lay Buddhist culture through the associated belief in karma and rebirth.[120] The Buddhist texts not only recommended Ahimsa, but suggest avoiding trading goods that contribute to or are a result of violence:

These five trades, O monks, should not be taken up by a lay follower: trading with weapons, trading in living beings, trading in meat, trading in intoxicants, trading in poison.

— Anguttara Nikaya V.177, Translated by Martine Batchelor[121]

Unlike lay Buddhists, transgressions by monks do invite sanctions.[122] Full expulsion of a monk from sangha follows instances of killing, just like any other serious offense against the monastic nikaya code of conduct.[122]

War

Violent ways of punishing criminals and prisoners of war was not explicitly condemned in Buddhism,[123] but peaceful ways of conflict resolution and punishment with the least amount of injury were encouraged.[124][125] The early texts condemn the mental states that lead to violent behavior.[126]

Nonviolence is an overriding theme within the Pali Canon.[127] While the early texts condemn killing in the strongest terms, and portray the ideal king as a pacifist, such a king is nonetheless flanked by an army.[128] It seems that the Buddha's teaching on nonviolence was not interpreted or put into practice in an uncompromisingly pacifist or anti-military-service way by early Buddhists.[128] The early texts assume war to be a fact of life, and well-skilled warriors are viewed as necessary for defensive warfare.[129] In Pali texts, injunctions to abstain from violence and involvement with military affairs are directed at members of the sangha; later Mahayana texts, which often generalise monastic norms to laity, require this of lay people as well.[130]

The early texts do not contain just-war ideology as such.[131] Some argue that a sutta in the Gamani Samyuttam rules out all military service. In this passage, a soldier asks the Buddha if it is true that, as he has been told, soldiers slain in battle are reborn in a heavenly realm. The Buddha reluctantly replies that if he is killed in battle while his mind is seized with the intention to kill, he will undergo an unpleasant rebirth.[132] In the early texts, a person's mental state at the time of death is generally viewed as having a great impact on the next birth.[133]

Some Buddhists point to other early texts as justifying defensive war.[134] One example is the Kosala Samyutta, in which King Pasenadi, a righteous king favored by the Buddha, learns of an impending attack on his kingdom. He arms himself in defence, and leads his army into battle to protect his kingdom from attack. He lost this battle but won the war. King Pasenadi eventually defeated King Ajatasattu and captured him alive. He thought that, although this King of Magadha has transgressed against his kingdom, he had not transgressed against him personally, and Ajatasattu was still his nephew. He released Ajatasattu and did not harm him.[135] Upon his return, the Buddha said (among other things) that Pasenadi "is a friend of virtue, acquainted with virtue, intimate with virtue", while the opposite is said of the aggressor, King Ajatasattu.[136]

According to Theravada commentaries, there are five requisite factors that must all be fulfilled for an act to be both an act of killing and to be karmically negative. These are: (1) the presence of a living being, human or animal; (2) the knowledge that the being is a living being; (3) the intent to kill; (4) the act of killing by some means; and (5) the resulting death.[137] Some Buddhists have argued on this basis that the act of killing is complicated, and its ethicization is predicated upon intent.[138] Some have argued that in defensive postures, for example, the primary intention of a soldier is not to kill, but to defend against aggression, and the act of killing in that situation would have minimal negative karmic repercussions.[139]

According to Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, there is circumstantial evidence encouraging Ahimsa, from the Buddha's doctrine, "Love all, so that you may not wish to kill any." Gautama Buddha distinguished between a principle and a rule. He did not make Ahimsa a matter of rule, but suggested it as a matter of principle. This gives Buddhists freedom to act.[140]

Laws

The emperors of Sui dynasty, Tang dynasty and early Song dynasty banned killing in Lunar calendar 1st, 5th, and 9th month.[141][142] Empress Wu Tse-Tien banned killing for more than half a year in 692.[143] Some also banned fishing for some time each year.[144]

There were bans after death of emperors,[145] Buddhist and Taoist prayers,[146] and natural disasters such as after a drought in 1926 summer Shanghai and an 8 days ban from August 12, 1959, after the August 7 flood (八七水災), the last big flood before the 88 Taiwan Flood.[147]

People avoid killing during some festivals, like the Taoist Ghost Festival,[148] the Nine Emperor Gods Festival, the Vegetarian Festival and many others.[149][150]

Methods

.jpg)

Nonviolent action generally comprises three categories: Acts of Protest and Persuasion, Noncooperation, and Nonviolent Intervention.[151]

Acts of protest

Nonviolent acts of protest and persuasion are symbolic actions performed by a group of people to show their support or disapproval of something. The goal of this kind of action is to bring public awareness to an issue, persuade or influence a particular group of people, or to facilitate future nonviolent action. The message can be directed toward the public, opponents, or people affected by the issue. Methods of protest and persuasion include speeches, public communications, petitions, symbolic acts, art, processions (marches), and other public assemblies.[152]

Noncooperation

Noncooperation involves the purposeful withholding of cooperation or the unwillingness to initiate in cooperation with an opponent. The goal of noncooperation is to halt or hinder an industry, political system, or economic process. Methods of noncooperation include labour strikes, economic boycotts, civil disobedience, sex strike, tax refusal, and general disobedience.[152]

Nonviolent intervention

Compared with protest and noncooperation, nonviolent intervention is a more direct method of nonviolent action. Nonviolent intervention can be used defensively—for example to maintain an institution or independent initiative—or offensively- for example, to drastically forward a nonviolent struggle into the opponent's territory. Intervention is often more immediate and effective than the other two methods, but is also harder to maintain and more taxing to the participants involved.

Gene Sharp, a political scientist who seeks to advance the worldwide study and use of strategic nonviolent action in conflict, has written extensively about the methods of nonviolent action. In his book Waging Nonviolent Struggle he describes 198 methods of nonviolent action.[153] In early Greece, Aristophanes' Lysistrata gives the fictional example of women withholding sexual favors from their husbands until war was abandoned. A modern work of fiction inspired by Gene Sharp and by Aristophanes is A Door into Ocean by Joan Slonczewski, depicting an ocean world inhabited by women who use nonviolent means to repel armed space invaders. Other methods of nonviolent intervention include occupations (sit-ins), blockades, fasting (hunger strikes), truck cavalcades, and dual sovereignty/parallel government.[152]

Tactics must be carefully chosen, taking into account political and cultural circumstances, and form part of a larger plan or strategy.

Successful nonviolent cross-border intervention projects include the Guatemala Accompaniment Project,[154] Peace Brigades International and Christian Peacemaker Teams. Developed in the early 1980s, and originally inspired by the Gandhian Shanti Sena, the primary tools of these organisations have been nonviolent protective accompaniment, backed up by a global support network which can respond to threats, local and regional grassroots diplomatic and peacebuilding efforts, human rights observation and witnessing, and reporting.[155][156] In extreme cases, most of these groups are also prepared to do interpositioning: placing themselves between parties who are engaged or threatening to engage in outright attacks in one or both directions. Individual and large group cases of interpositioning, when called for, have been remarkably effective in dampening conflict and saving lives.

Another powerful tactic of nonviolent intervention invokes public scrutiny of the oppressors as a result of the resisters remaining nonviolent in the face of violent repression. If the military or police attempt to repress nonviolent resisters violently, the power to act shifts from the hands of the oppressors to those of the resisters. If the resisters are persistent, the military or police will be forced to accept the fact that they no longer have any power over the resisters. Often, the willingness of the resisters to suffer has a profound effect on the mind and emotions of the oppressor, leaving them unable to commit such a violent act again.[157][158]

Revolution

Certain individuals (Barbara Deming, Danilo Dolci, Devere Allen etc.) and party groups (e.g. Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism, Pacifist Socialist Party or War Resisters League) have advocated nonviolent revolution as an alternative to violence as well as elitist reformism. This perspective is usually connected to militant anti-capitalism.

Many leftist and socialist movements have hoped to mount a "peaceful revolution" by organising enough strikers to completely paralyse the state and corporate apparatus, allowing workers to re-organise society along radically different lines. Some have argued that a relatively nonviolent revolution would require fraternisation with military forces.[159]

Criticism

Ernesto Che Guevara, Leon Trotsky, Frantz Fanon and Subhas Chandra Bose were fervent critics of nonviolence, arguing variously that nonviolence and pacifism are an attempt to impose the morals of the bourgeoisie upon the proletariat, that violence is a necessary accompaniment to revolutionary change or that the right to self-defense is fundamental. Note, for example, the complaint of Malcolm X that "I believe it's a crime for anyone being brutalized to continue to accept that brutality without doing something to defend himself."[160]

George Orwell argued that the nonviolent resistance strategy of Gandhi could be effective in countries with "a free press and the right of assembly", which could make it possible "not merely to appeal to outside opinion, but to bring a mass movement into being, or even to make your intentions known to your adversary"; but he was skeptical of Gandhi's approach being effective in the opposite sort of circumstances.[161]

Reinhold Niebuhr similarly affirmed Gandhi's approach while criticising aspects of it. He argued, "The advantage of non-violence as a method of expressing moral goodwill lies in the fact that it protects the agent against the resentments which violent conflict always creates in both parties to a conflict, and it proves this freedom of resentment and ill-will to the contending party in the dispute by enduring more suffering than it causes." However, Niebuhr also held, "The differences between violent and non-violent methods of coercion and resistance are not so absolute that it would be possible to regard violence as a morally impossible instrument of social change."[162]

In the midst of repression of radical African American groups in the United States during the 1960s, Black Panther member George Jackson said of the nonviolent tactics of Martin Luther King Jr.:

"The concept of nonviolence is a false ideal. It presupposes the existence of compassion and a sense of justice on the part of one's adversary. When this adversary has everything to lose and nothing to gain by exercising justice and compassion, his reaction can only be negative."[163][164]

Malcolm X also clashed with civil rights leaders over the issue of nonviolence, arguing that violence should not be ruled out if no option remained.

In his book How Nonviolence Protects the State, anarchist Peter Gelderloos criticises nonviolence as being ineffective, racist, statist, patriarchal, tactically and strategically inferior to militant activism, and deluded.[165] Gelderloos claims that traditional histories whitewash the impact of nonviolence, ignoring the involvement of militants in such movements as the Indian independence movement and the Civil Rights Movement and falsely showing Gandhi and King as being their respective movement's most successful activists.[165]:7–12 He further argues that nonviolence is generally advocated by privileged white people who expect "oppressed people, many of whom are people of color, to suffer patiently under an inconceivably greater violence, until such time as the Great White Father is swayed by the movement's demands or the pacifists achieve that legendary 'critical mass.'"[165]:23 On the other hand, anarchism also includes a section committed to nonviolence called anarcho-pacifism.[166][167] The main early influences were the thought of Henry David Thoreau[167] and Leo Tolstoy while later the ideas of Mohandas Gandhi gained importance.[166][167] It developed "mostly in Holland, Britain, and the United States, before and during the Second World War".[168]

The efficacy of nonviolence was also challenged by some anti-capitalist protesters advocating a "diversity of tactics" during street demonstrations across Europe and the US following the anti-World Trade Organization protests in Seattle, Washington in 1999. American feminist writer D. A. Clarke, in her essay "A Woman With A Sword," suggests that for nonviolence to be effective, it must be "practiced by those who could easily resort to force if they chose."

Nonviolence advocates see some truth in this argument: Gandhi himself said often that he could teach nonviolence to a violent person but not to a coward and that true nonviolence came from renouncing violence, not by not having any to renounce.

Advocates responding to criticisms of the efficacy of nonviolence point to the limited success of non-violent struggles even against the Nazi regimes in Denmark and even in Berlin.[169] A study by Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan found that nonviolent revolutions are twice as effective as violent ones and lead to much greater degrees of democratic freedom.[170]

Research

A 2016 study finds that "increasing levels of globalization are positively associated with the emergence of nonviolent campaigns, while negatively influencing the probability of violent campaigns. Integration into the world increases the popularity of peaceful alternatives to achieve political goals."[171] A 2020 study found that nonviolent campaigns were more likely to succeed when there was not an ethnic division between actors in the campaign and in the government.[172] According to a 2020 study in the American Political Science Review, nonviolent civil rights protests boosted vote shares for the Democratic party in presidential elections in nearby counties, but violent protests substantially boosted white support for Republicans in counties near to the violent protests.[173]

See also

- Category:Nonviolence organizations

- Ahimsa

- Anti-war

- Christian anarchism

- Christian pacifism

- Conflict resolution

- Consistent life ethic

- Department of Peace

- Draft evasion, see Draft resistance

- List of peace activists

- "Mahavira: The Hero of Nonviolence"

- Non-aggression principle

- Nonkilling

- Nonresistance

- Nonviolence International

- Nonviolent Communication

- Pacifism

- Padayatra

- Passive resistance

- Satyagraha

- Season for Nonviolence

- Social defence

- Third Party Non-violent Intervention

- Turning the other cheek

- Violence begets violence

- War resister

References

Citations

- A clarification of this and related terms appears in Gene Sharp, Sharp's Dictionary of Power and Struggle: Language of Civil Resistance in Conflicts, Oxford University Press, New York, 2012.

- Ronald Brian Adler, Neil Towne, Looking Out/Looking In: Interpersonal Communication, 9th ed. Harcourt Brace College Publishers, p. 416, 1999. "In the twentieth century, nonviolence proved to be a powerful tool for political change."

- Lester R. Kurtz, Jennifer E. Turpin, Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, and Conflict, p.557, 1999. "In the West, nonviolence is well recognized for its tactical, strategic, or political aspects. It is seen as a powerful tool for redressing social inequality."

- Mark Kurlansky, Nonviolence: The History of a Dangerous Idea, Foreword by Dalai Lama, p. 5-6, Modern Library (April 8, 2008), ISBN 0-8129-7447-6 "Advocates of nonviolence — dangerous people — have been there throughout history, questioning the greatness of Caesar and Napoleon and the Founding Fathers and Roosevelt and Churchill."

- "James L. Bevel The Strategist of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement" by Randy Kryn, a paper in David Garrow's 1989 book We Shall Overcome Volume II, Carlson Publishing Company

- "Movement Revision Research Summary Regarding James Bevel" by Randy Kryn, October 2005, published by Middlebury College

- Stanley M. Burstein and Richard Shek: "World History Ancient Civilizations ", page 154. Holt, Rinhart and Winston, 2005. As Chavez once explained, "Nonviolence is not inaction. It is not for the timid or the weak. It is hard work, it is the patience to win."

- "RP's History Online - Velvet Revolution". Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- Ives, Susan (19 October 2001). "No Fear". Palo Alto College. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- Chris Graham, Peacebuilding alum talks practical app of nonviolence Archived 2009-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, Augusta Free Press, October 26, 2009.

- Ackerman, Peter and Jack DuVall (2001) "A Force More Powerful: A Century of Non-Violent Conflict"(Palgrave Macmillan)

- Adam Roberts, Introduction, in Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present, Oxford University Press, 2009 pp. 3 and 13-20.

- Pandey, Janardan (1998), Gandhi and 21st Century, p. 50, ISBN 978-81-7022-672-7

- Stephen H. Phillips & other authors (2008), in Encyclopedia of Violence, Peace, & Conflict (Second Edition), ISBN 978-0-12-373985-8, Elsevier Science, Pages 1347–1356, 701–849, 1867

- John Arapura in K. R. Sundararajan and Bithika Mukerji Ed. (1997), Hindu spirituality: Postclassical and modern, ISBN 978-81-208-1937-5; see Chapter 20, pages 392–417

- Chapple, C. (1990). Nonviolence to animals, earth and self in Asian Traditions (see Chapter 1). State University of New York Press (1993)

- Patel, Haresh (March 2009). Thoughts from the Cosmic Field in the Life of a Thinking Insect [A Latter-Day Saint]. ISBN 9781606938461.

- "Parshvanatha", britannica.com

- "Mahavira", britannica.com

- Sharp, Gene (1973). The Politics of Nonviolent Action. Porter Sargent. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-87558-068-5.

- Two Kinds of Nonviolent Resistance ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- Nonviolent Resistance & Political Power ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans (U.S.)

- Nicolas Walter, "Non-Violent Resistance:Men Against War". Reprinted in Nicolas Walter, Damned Fools in Utopia edited by David Goodway. PM Press 2010. ISBN 160486222X (pp. 37-78).

- Martin Luther King, Jr. (2010-01-01). Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story. Beacon Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8070-0070-0.

- "Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: The Making of Buddhist Texts" (12 July 2014). University of Cambridge (www.Cam.ac.uk). Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Vogeler, Ingolf. "Jainism in India" University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire (UWEC.edu). Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Tirukkuṛaḷ Archived 2014-12-16 at the Wayback Machine verses 311-320

- Pope, GU (1886). Thirukkural English Translation and Commentary (PDF). W.H. Allen, & Co. p. 160.

- Csilla Dallos (2011). From Equality to Inequality: Social Change Among Newly Sedentary Lanoh Hunter-Gatherer Traders of Peninsular Malaysia. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-144-2661-71-4.

- Dentan, Robert Knox (1968). "The Semai: A Nonviolent People Of Malaya". Case Studies In Cultural Anthropology. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Leary, John. Violence and the Dream People: The Orang Asli in the Malayan Emergency, 1948-1960. No. 95. Ohio University Press, 1995, p.262

- Leary, John. Violence and the Dream People: The Orang Asli in the Malayan Emergency, 1948-1960. No. 95. Ohio University Press, 1995.

- Robarchek, Clayton A., and Robert Knox Dentan. "Blood drunkenness and the bloodthirsty Semai: Unmaking another anthropological myth." American Anthropologist 89, no. 2 (1987): 356-365

- Walli, Koshelya: The Conception of Ahimsa in Indian Thought, Varanasi 1974, p. 113–145.

- Sanskrit: अस्मे ता त इन्द्र सन्तु सत्याहिंसन्तीरुपस्पृशः । विद्याम यासां भुजो धेनूनां न वज्रिवः ॥१३॥ Rigveda 10.22 Wikisource;

English: Unto Tähtinen (1964), Non-violence as an Ethical Principle, Turun Yliopisto, Finland, PhD Thesis, pages 23–25; OCLC 4288274;

For other occurrence of Ahimsa in Rigveda, see Rigveda 5.64.3, Rigveda 1.141.5; - To do no harm Archived 2013-10-17 at the Wayback Machine Project Gutenberg, see translation for Yajurveda 36.18 VE;

For other occurrences of Ahimsa in Vedic literature, see A Vedic Concordance Maurice Bloomfield, Harvard University Press, page 151 - Tähtinen p. 2.

- Shatapatha Brahmana 2.3.4.30; 2.5.1.14; 6.3.1.26; 6.3.1.39.

- Henk M. Bodewitz in Jan E. M. Houben, K. R. van Kooij, ed., Violence denied: violence, non-violence and the rationalisation of violence in "South Asian" cultural history. BRILL, 1999 page 30.

- Tähtinen pp. 2–3.

- John Bowker, Problems of suffering in religions of the world. Cambridge University Press, 1975, page 233.

- Kaneda, T. (2008). Shanti, peacefulness of mind. C. Eppert & H. Wang (Eds.), Cross cultural studies in curriculum: Eastern thought, educational insights, pages 171–192, ISBN 978-0-8058-5673-6, Taylor & Francis

- Izawa, A. (2008). Empathy for Pain in Vedic Ritual. Journal of the International College for Advanced Buddhist Studies, 12, 78

- Tähtinen pp. 2–5; English translation: Schmidt p. 631.

- M.K Sridhar and Puruṣottama Bilimoria (2007), Indian Ethics: Classical traditions and contemporary challenges, Editors: Puruṣottama Bilimoria, Joseph Prabhu, Renuka M. Sharma, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-3301-3, page 315

- Jeffery D. Long (2009). Jainism: An Introduction. I. B. Tauris. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-1-84511-625-5.

- Paul Dundas (2002). The Jains. Routledge. pp. 22–24, 73–83. ISBN 978-0415266055.

- Ravindra Kumar (2008), Non-violence and Its Philosophy, ISBN 978-81-7933-159-0, see page 11–14

- Swami, P. (2000). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Upaniṣads: SZ (Vol. 3). Sarup & Sons; see pages 630–631

- Ballantyne, J. R., & Yogīndra, S. (1850). A Lecture on the Vedánta: Embracing the Text of the Vedánta-sára. Presbyterian mission press.

- Mahabharata 13.117.37–38

- Chapple, C. (1990). Ecological Nonviolence and the Hindu Tradition. In Perspectives on Nonviolence (pp. 168–177). Springer New York.

- Ahimsa: To do no harm Subramuniyaswami, What is Hinduism?, Chapter 45, Pages 359–361

- Fischer, Louis: Gandhi: His Life and Message to the World Mentor, New York 1954, pp. 15–16

- Balkaran, R., & Dorn, A. W. (2012). Violence in the Vālmı̄ki Rāmāyaṇa: Just War Criteria in an Ancient Indian Epic, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 80(3), 659–690.

- Klaus K. Klostermaier (1996), in Harvey Leonard Dyck and Peter Brock (Ed), The Pacifist Impulse in Historical Perspective, see Chapter on Himsa and Ahimsa Traditions in Hinduism, ISBN 978-0-8020-0777-3, University of Toronto Press, pages 230–234

- Paul F. Robinson (2003), Just War in Comparative Perspective, ISBN 0-7546-3587-2, Ashgate Publishing, see pages 114–125

- Coates, B. E. (2008). Modern India's Strategic Advantage to the United States: Her Twin Strengths in Himsa and Ahimsa. Comparative Strategy, 27(2), pages 133–147

- Subedi, S. P. (2003). The Concept in Hinduism of 'Just War'. Journal of Conflict and Security Law, 8(2), pages 339–361

- Tähtinen pp. 96, 98–101.

- Mahabharata 12.15.55; Manu Smriti 8.349–350; Matsya Purana 226.116.

- Tähtinen pp. 91–93.

- The Role of Teachers in Martial Arts Nebojša Vasic, University of Zenica (2011); Sport SPA Vol. 8, Issue 2: 47–51; see page 46, 2nd column

- SOCIAL CONFLICT, AGGRESSION, AND THE BODY IN EURO-AMERICAN AND ASIAN SOCIAL THOUGHT Donald Levine, University of Chicago (2004)

- Ueshiba, Kisshōmaru (2004), The Art of Aikido: Principles and Essential Techniques, Kodansha International, ISBN 4-7700-2945-4

- Tähtinen pp. 96, 98–99.

- Christopher Chapple (1993), Nonviolence to Animals, Earth, and Self in Asian Traditions, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-1498-1, pages 16–17

- W Norman Brown (February 1964), The sanctity of the cow in Hinduism, The Economic Weekly, pages 245–255

- D.N. Jha (2002), The Myth of the Holy Cow, ISBN 1-85984-676-9, Verso

- Steven Rosen (2004), Holy Cow: The Hare Krishna Contribution to Vegetarianism and Animal Rights, ISBN 1-59056-066-3, pages 19–39

- Baudhayana Dharmasutra 2.4.7; 2.6.2; 2.11.15; 2.12.8; 3.1.13; 3.3.6; Apastamba Dharmasutra 1.17.15; 1.17.19; 2.17.26–2.18.3; Vasistha Dharmasutra 14.12.

- Manu Smriti 5.30, 5.32, 5.39 and 5.44; Mahabharata 3.199 (3.207), 3.199.5 (3.207.5), 3.199.19–29 (3.207.19), 3.199.23–24 (3.207.23–24), 13.116.15–18, 14.28; Ramayana 1-2-8:19

- Alsdorf pp. 592–593.

- Mahabharata 13.115.59–60; 13.116.15–18.

- Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna (1907), An English Translation of the Sushruta Samhita, Volume I, Part 2; see Chapter starting on page 469; for discussion on meats and fishes, see page 480 and onwards

- Sutrasthana 46.89; Sharirasthana 3.25.

- Sutrasthana 27.87.

- Mahabharata 3.199.11–12 (3.199 is 3.207 elsewhere); 13.115; 13.116.26; 13.148.17; Bhagavata Purana (11.5.13–14), and the Chandogya Upanishad (8.15.1).

- Alsdorf pp. 572–577 (for the Manusmṛti) and pp. 585–597 (for the Mahabharata); Tähtinen pp. 34–36.

- The Mahabharata and the Manusmṛti (5.27–55) contain lengthy discussions about the legitimacy of ritual slaughter.

- Mahabharata 12.260 (12.260 is 12.268 according to another count); 13.115–116; 14.28.

- Mahabharata 3.199 (3.199 is 3.207 according to another count).

- Tähtinen pp. 39–43.

- Alsdorf p. 589–590; Schmidt pp. 634–635, 640–643; Tähtinen pp. 41–42.

- Schmidt pp. 637–639; Manusmriti 10.63, 11.145

- Rod Preece, Animals and Nature: Cultural Myths, Cultural Realities, ISBN 978-0-7748-0725-8, University of British Columbia Press, pages 212–217

- Chapple, C. (1990). Ecological Nonviolence and the Hindu Tradition. In Perspectives on Nonviolence (pages 168–177). Springer New York

- Van Horn, G. (2006). Hindu Traditions and Nature: Survey Article. Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology, 10(1), 5–39

- Tirukkuṛaḷ Translated by Rev G.U. Pope, Rev W.H. Drew, Rev John Lazarus, and Mr F W Ellis (1886), WH Allen & Company; see pages 40–41, verses 311–330

- Tirukkuṛaḷ Archived 16 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine see Chapter 32 and 33, Book 1

- Tirukkuṛaḷ Translated by V.V.R. Aiyar, Tirupparaithurai : Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam (1998)

- Laidlaw, pp. 154–160; Jindal, pp. 74–90; Tähtinen p. 110.

- Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 34.

- Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 33.

- Dundas pp. 158–159, 189–192; Laidlaw pp. 173–175, 179; Religious Vegetarianism, ed. Kerry S. Walters and Lisa Portmess, Albany 2001, p. 43–46 (translation of the First Great Vow).

- Dundas, Paul: The Jains, second edition, London 2002, p. 160; Wiley, Kristi L.: Ahimsa and Compassion in Jainism, in: Studies in Jaina History and Culture, ed. Peter Flügel, London 2006, p. 438; Laidlaw pp. 153–154.

- Laidlaw pp. 26–30, 191–195.

- Dundas p. 24 suggests the 5th century; the traditional dating of lord Mahaviraswami's death is 527 BCE.

- Dundas pp. 19, 30; Tähtinen p. 132.

- Dundas p. 30 suggests the 8th or 7th century; the traditional chronology places him in the late 9th or early 8th century.

- Acaranga Sutra 2.15.

- Sthananga Sutra 266; Tähtinen p. 132; Goyal p. 83–84, 103.

- Dundas pp. 160, 234, 241; Wiley p. 448; Granoff, Phyllis: The Violence of Non-Violence: A Study of Some Jain Responses to Non-Jain Religious Practices, in: Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 15 (1992) pp. 1–43; Tähtinen pp. 8–9.

- Laidlaw p. 169.

- Laidlaw pp. 166–167; Tähtinen p. 37.

- Lodha, R.M.: Conservation of Vegetation and Jain Philosophy, in: Medieval Jainism: Culture and Environment, New Delhi 1990, p. 137–141; Tähtinen p. 105.

- Jindal p. 89; Laidlaw pp. 54, 154–155, 180.

- Sutrakrtangasutram 1.8.3; Uttaradhyayanasutra 10; Tattvarthasutra 7.8; Dundas pp. 161–162.

- Hemacandra: Yogashastra 3.37; Laidlaw pp. 166–167.

- Laidlaw p. 180.

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath: Jaina Community. A Social Survey, second edition, Bombay 1980, p. 259; Dundas p. 191.

- Jindal pp. 89, 125–133 (detailed exposition of the classification system); Tähtinen pp. 17, 113.

- Nisithabhasya (in Nisithasutra) 289; Jinadatta Suri: Upadesharasayana 26; Dundas pp. 162–163; Tähtinen p. 31.

- Jindal pp. 89–90; Laidlaw pp. 154–155; Jaini, Padmanabh S.: Ahimsa and "Just War" in Jainism, in: Ahimsa, Anekanta and Jainism, ed. Tara Sethia, New Delhi 2004, p. 52–60; Tähtinen p. 31.

- Harisena, Brhatkathakosa 124 (10th century); Jindal pp. 90–91; Sangave p. 259.

- Paul Williams (2005). Buddhism: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies. Routledge. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-415-33226-2.

- Bodhi Bhikkhu (1997). Great Disciples of the Buddha: Their Lives, Their Works, Their Legacy. Wisdom Publications. pp. 387 with footnote 12. ISBN 978-0-86171-128-4.;

Sarao, p. 49; Goyal p. 143; Tähtinen p. 37. - Lamotte, pp. 54–55.

- McFarlane 2001, p. 187.

- McFarlane 2001, pp. 187–191.

- Martine Batchelor (2014). The Spirit of the Buddha. Yale University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-300-17500-4.

- McFarlane 2001, p. 192.

- Sarao p. 53; Tähtinen pp. 95, 102.

- Tähtinen pp. 95, 102–103.

- Kurt A. Raaflaub, War and Peace in the Ancient World. Blackwell Publishing, 2007, p. 61.

- Bartholomeusz, p. 52.

- Bartholomeusz, p. 111.

- Bartholomeusz, p. 41.

- Bartholomeusz, p. 50.

- Stewart McFarlane in Peter Harvey, ed., Buddhism. Continuum, 2001, pages 195–196.

- Bartholomeusz, p. 40.

- Bartholomeusz, pp. 125–126. Full texts of the sutta:.

- Rune E.A. Johansson, The Dynamic Psychology of Early Buddhism. Curzon Press 1979, page 33.

- Bartholomeusz, pp. 40–53. Some examples are the Cakkavati Sihanada Sutta, the Kosala Samyutta, the Ratthapala Sutta, and the Sinha Sutta. See also page 125. See also Trevor Ling, Buddhism, Imperialism, and War. George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1979, pages 136–137.

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (trans.) (2000). The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-331-1.

- Bartholomeusz, pp. 49, 52–53.

- Hammalawa Saddhatissa, Buddhist Ethics. Wisdom Publications, 1997, pages 60, 159, see also Bartholomeusz page 121.

- Bartholomeusz, p. 121.

- Bartholomeusz, pp. 44, 121–122, 124.

- The Buddha and His Dhamma. Columbia.edu. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- 卷糺 佛教的慈悲觀. Bya.org.hk. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- 試探《護生畫集》的護生觀 高明芳

- 「護生」精神的實踐舉隅. Ccbs.ntu.edu.tw. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- 答妙贞十问. Cclw.net. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- 第一二八期 佛法自由談. Bya.org.hk. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- 虛雲和尚法彙—書問. Bfnn.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- 道安長老年譜 Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine. Plela.org. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- 农历中元节. Sx.chinanews.com.cn. Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- 明溪县“禁屠日”习俗的由来

- 建构的节日:政策过程视角下的唐玄宗诞节. Chinesefolklore.org.cn (2008-02-16). Retrieved on 2011-06-15.

- United Nations International Day of Non-Violence, United Nations, 2008. see International Day of Non-Violence.

- Sharp, Gene (2005). Waging Nonviolent Struggle. Extending Horizon Books. pp. 50–65. ISBN 978-0-87558-162-0.

- Sharp, Gene (1973). "The Methods of Nonviolent Action". Peace magazine. Retrieved 2008-11-07. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Network in Solidarity with the People of Guatemala

- "PBI's principles". Peace Brigades International. PBI General Assembly. 2001 [1992]. Archived from the original on 2010-06-02. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- "Christian Peace Maker Teams Mission Statement". Christian Peacemaker Team. CPT founding conference. 1986. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- Sharp, Gene (1973). The Politics of Nonviolent Action. P. Sargent Publisher. p. 657. ISBN 978-0-87558-068-5.

- Sharp, Gene (2005). Waging Nonviolent Struggle. Extending Horizon Books. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-87558-162-0.

- Daniel Jakopovich: Revolution and the Party in Gramsci's Thought: A Modern Application.

- X, Malcolm and Alex Haley:"The Autobiography of Malcolm X", page 366. Grove Press, 1964

- Dag, O. "George Orwell: Reflections on Gandhi". www.orwell.ru. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- "IraChernus-NiebuhrSection6". 2015-09-23. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- Jackson, George. Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson. Lawrence Hill Books, 1994. ISBN 1-55652-230-4

- Walters, Wendy W. At Home in Diaspora. U of Minnesota Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8166-4491-8

- Gelderloos, Peter. How Nonviolence Protects the State. Boston: South End Press, 2007.

- George Woodcock. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (1962)

- ""Resisting the Nation State, the pacifist and anarchist tradition" by Geoffrey Ostergaard". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- Woodstock, George (1962). Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements.

Finally, somewhat aside from the curve that runs from anarchist individualism to anarcho-syndicalism, we come to Tolstoyanism and to pacifist anarchism that appeared, mostly in the Netherlands, Britain, and the United states, before and after the Second World War and which has continued since then in the deep in the anarchist involvement in the protests against nuclear armament.

- Nathan Stoltzfus, Resistance of the Heart: Intermarriage and the Rosenstrasse Protest in Nazi Germany, Rutgers University Press (March 2001) ISBN 0-8135-2909-3 (paperback: 386 pages)

- "Why Civil Resistance Works, The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict", New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

- Karakaya, Süveyda (2018). "Globalization and contentious politics: A comparative analysis of nonviolent and violent campaigns". Conflict Management and Peace Science. 35 (4): 315–335. doi:10.1177/0738894215623073. ISSN 0738-8942.

- Pischedda, Costantino (2020-02-12). "Ethnic Conflict and the Limits of Nonviolent Resistance". Security Studies. 0: 1–30. doi:10.1080/09636412.2020.1722854. ISSN 0963-6412.

- Wasow, Omar (2020). "Agenda Seeding: How 1960s Black Protests Moved Elites, Public Opinion and Voting". American Political Science Review: 1–22. doi:10.1017/S000305542000009X. ISSN 0003-0554.

Sources

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya: Realization of the Pure Self, With Hindi and English Translation, Vikalp, ISBN 978-81-903639-4-5,

- True, Michael (1995), An Energy Field More Intense Than War, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0-8156-2679-4

Further reading

- ISBN 978-1577663492 Nonviolence in Theory and Practice, edited by Robert L. Holmes and Barry L. Gan

- OCLC 03859761 The Kingdom of God Is Within You, by Leo Tolstoy

- ISBN 978-0-85066-336-5 Making Europe Unconquerable: the Potential of Civilian-Based Deterrence and Defense (see article), by Gene Sharp

- ISBN 0-87558-162-5 Waging Nonviolent Struggle: 20th Century Practice And 21st Century Potential, by Gene Sharp with collaboration of Joshua Paulson and the assistance of Christopher A. Miller and Hardy Merriman

- ISBN 978-1442217607 Violence and Nonviolence: An Introduction, by Barry L. Gan

- ISBN 0-8166-4193-5 Unarmed Insurrections: People Power Movements in Non-Democracies, by Kurt Schock

- ISBN 1-930722-35-4 Is There No Other Way? The Search for a Nonviolent Future, by Michael Nagler

- ISBN 0-85283-262-1 People Power and Protest since 1945: A Bibliography of Nonviolent Action, compiled by April Carter, Howard Clark, and [Michael Randle]

- ISBN 978-953-55134-2-1 Revolutionary Peacemaking: Writings for a Culture of Peace and Nonviolence, by Daniel Jakopovich

- ISBN 978-0-903517-21-8 Handbook for Nonviolent Campaigns, War Resisters' International

- ISBN 978-0-19-955201-6 Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present, ed. Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash, Oxford University Press, 2009. (hardback).

- How to Start a Revolution, documentary directed by Ruaridh Arrow

- A Force More Powerful, documentary directed by Steve York

- https://web.archive.org/web/20190416053057/http://nonviolentaction.net/ Expanded database of 300 nonviolent methods and examples

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nonviolence |