Alberta Williams King

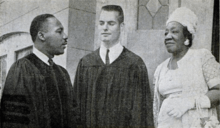

Alberta Christine Williams King (September 13, 1904 – June 30, 1974) was Martin Luther King, Jr.'s mother and the wife of Martin Luther King, Sr. She played a significant role in the affairs of the Ebenezer Baptist Church. She was shot and killed in the church by Marcus Wayne Chenault, a 23-year-old Black Hebrew Israelite, six years after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.[1]

Alberta Williams King | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Alberta Christine Williams September 13, 1904 Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | June 30, 1974 (aged 69) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Spelman Seminary Hampton University Morris Brown College |

| Spouse(s) | Martin Luther King, Sr. ( m. 1926) |

| Children | Christine King Farris Martin Luther King, Jr. Alfred Daniel Williams King I |

| Parent(s) | Reverend Adam Daniel Williams (1863-1931) Jennie Celeste Parks Williams (1873-1941) |

Life and career

Alberta Christine Williams was born on September 13, 1904, to Reverend Adam Daniel Williams, at the time preacher of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, and Jennie Celeste (Parks) Williams.[2] Alberta Williams graduated from high school at the Spelman Seminary, and earned a teaching certificate at the Hampton Normal and Industrial Institute (now Hampton University) in 1924.

Williams met Martin L. King (then known as Michael King), whose sister Woodie was boarding with her parents, shortly before she left for Hampton. After graduating, she announced her engagement to King at the Ebenezer Baptist Church. She taught for a short time before their Thanksgiving Day 1926 wedding, but she had to quit because married female teachers were not then allowed.

Their first child, daughter Willie Christine King, was born on September 11, 1927. Michael Luther King Jr. followed on January 15, 1929, then Alfred Daniel Williams King I, named after his grandfather, on July 30, 1930. About this time, Michael King changed his name to Martin Luther King, Sr.

Alberta King worked hard to instil self-respect into her children. In an essay he wrote at Crozer Seminary, Martin Luther King Jr., who was always close to her, wrote that she "was behind the scenes setting forth those motherly cares, the lack of which leaves a missing link in life."

Alberta King's mother died on May 18, 1941, of a heart attack. The King family later moved to a large yellow brick house three blocks away. Alberta would serve as the organizer and president of the Ebenezer Women's Committee from 1950 to 1962. She was also a talented musician who served as the choir organist and director at Ebenezer, which may have contributed to the respect her son had for the music.[3] By the end of this period, Martin Luther King Sr. and Jr. were joint pastors of the church.

Family tragedies, 1968–1974

Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. King was in Memphis to lead a march in support of the local sanitation workers' union. He was pronounced dead one hour later. Mrs. King, a source of strength after her son's assassination, faced fresh tragedy the next year when her younger son and last-born child, Alfred Daniel Williams King, who had become the assistant pastor at the Ebenezer Baptist Church, drowned in his pool.

Assassination

Alberta King was shot and killed on June 30, 1974, at age 69, by Marcus Wayne Chenault, a 23-year-old black man from Ohio who had adopted an extremist version of the theology of the Black Hebrew Israelites.[4] Chenault's mentor, Rev. Hananiah E. Israel of Cincinnati, castigated black civil rights activists and black church leaders as being evil and deceptive, but claimed in interviews not to have advocated violence.[5] Chenault did not draw any such distinction, and actually first decided to assassinate Rev. Jesse Jackson in Chicago, but canceled the plan at the last minute. Two weeks later he set out for Atlanta, where he shot Alberta King with two handguns as she sat at the organ of the Ebenezer Baptist Church. Chenault said that he shot King because "all Christians are my enemies," and claimed that he had decided that black ministers were a menace to black people. He said his original target had been Martin Luther King, Sr., but he had decided to shoot his wife instead because she was near him. He also killed one of the church's deacons, Edward Boykin, in the attack, and wounded another woman, Mrs. Jimmie Mitchell.

Assassin's conviction

Chenault was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. The sentence was upheld on appeal, but he was later resentenced to life in prison, partially as a result of the King family's opposition to the death penalty. On August 3, 1995, he suffered a stroke, and was taken to a hospital, where he died at age 44 of complications from his stroke on August 19.[6][7]

Burial

Alberta King was interred at the South-View Cemetery in Atlanta. Martin Luther King, Sr., died of a heart attack on November 11, 1984, at age 84 and was interred next to her.

Notes

- Winchester, Simon. "From the archive, 1 July 1974: Martin Luther King's mother slain in church Alberta King, mother of the late Rev Martin Luther King, was shot and killed today by Marcus Wayne Chenut as she played the organ for morning service". Guardian.

- Ancestry of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr

- Lewis V. Baldwin, The Voice of Conscience: The Church in the Mind of Martin Luther King, Jr (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010, 27)

- "Slaying of Mrs. Martin Luther King Sr." The Decatur Daily Review, July 3, 1974, p.6

- "I Gave Marcus the Key" Dayton Daily News, July 3, 1974, pp.1, 15

- The Seattle Times: Living: Martin King 3rd: living up to society's expectations

- Saxon, Wolfgang (August 22, 1995). "M. W. Chenault, 44, Gunman Who Killed Mother of Dr. King". New York Times.

References

- The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. Volume I: Called to Serve, January 1929-June 1951 (University of California Press, 1992) Introduction

- The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. (New York: Warner Book, 1998) Chapter 1 edited by Clayborne Carson

- Martin Luther King, Jr., "Autobiography of Religious Development," 22 November 1950

- Daddy King and Me: Memories of the Forgotten Father of the Civil Rights Movement. Continental Shelf Publishing, 2009; Chapter Four, p. 69.