Virtue

Virtue (Latin: virtus, Ancient Greek: ἀρετή "arete") is moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. Personal virtues are characteristics valued as promoting collective and individual greatness. In other words, it is a behavior that shows high moral standards. Doing what is right and avoiding what is wrong. The opposite of virtue is vice.

The four classic cardinal virtues in Christianity are temperance, prudence, courage (or fortitude), and justice. Christianity derives the three theological virtues of faith, hope and love (charity) from 1 Corinthians 13. Together these make up the seven virtues. Buddhism's four brahmavihara ("Divine States") can be regarded as virtues in the European sense.[1][2]

Etymology

The ancient Romans used the Latin word virtus (derived from vir, their word for man) to refer to all of the "excellent qualities of men, including physical strength, valorous conduct, and moral rectitude." The French words vertu and virtu came from this Latin root. In the 13th century, the word virtue was "borrowed into English".[3]

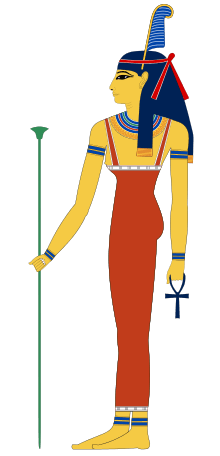

Ancient Egypt

During Egyptian civilization, Maat or Ma'at (thought to have been pronounced *[muʔ.ʕat]), also spelled māt or mayet, was the ancient Egyptian concept of truth, balance, order, law, morality, and justice. Maat was also personified as a goddess regulating the stars, seasons, and the actions of both mortals and the deities. The deities set the order of the universe from chaos at the moment of creation. Her (ideological) counterpart was Isfet, who symbolized chaos, lies, and injustice.[5][6]

Greco-Roman antiquity

Platonic virtue

The four classic cardinal virtues are:[7]

- temperance: σωφροσύνη (sōphrosynē)

- prudence: φρόνησις (phronēsis)

- courage: ἀνδρεία (andreia)

- justice: δικαιοσύνη (dikaiosynē)

This enumeration is traced to Greek philosophy and was listed by Plato in addition to piety: ὁσιότης (hosiotēs), with the exception that wisdom replaced prudence as virtue.[8] Some scholars[9] consider either of the above four virtue combinations as mutually reducible and therefore not cardinal.

It is unclear whether multiple virtues were of later construct, and whether Plato subscribed to a unified view of virtues.[10] In Protagoras and Meno, for example, he states that the separate virtues cannot exist independently and offers as evidence the contradictions of acting with wisdom, yet in an unjust way; or acting with bravery (fortitude), yet without wisdom.

Aristotelian virtue

In his work Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle defined a virtue as a point between a deficiency and an excess of a trait.[11] The point of greatest virtue lies not in the exact middle, but at a golden mean sometimes closer to one extreme than the other. However, the virtuous action is not simply the "mean" (mathematically speaking) between two opposite extremes. As Aristotle says in the Nicomachean Ethics: "at the right times, about the right things, towards the right people, for the right end, and in the right way, is the intermediate and best condition, and this is proper to virtue."[12] This is not simply splitting the difference between two extremes. For example, generosity is a virtue between the two extremes of miserliness and being profligate. Further examples include: courage between cowardice and foolhardiness, and confidence between self-deprecation and vanity. In Aristotle's sense, virtue is excellence at being human.

Epicurean virtue

Epicurean ethics call for a rational pursuit of pleasure with the aid of the virtues. The Epicureans teach that the emotions, dispositions and habits related to virtue (and vice) have a cognitive component and are based on true (or false) beliefs. By making sure that his beliefs are aligned with nature and by getting rid of empty opinions, the Epicurean develops a virtuous character in accordance with nature, and this helps him to live pleasantly.[13]

Pyrrhonist virtue

The Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus described Pyrrhonism as "a way of life that, in accordance with appearances, follows a certain rationale, where that rationale shows how it is possible to seem to live rightly ("rightly" being taken, not as referring only to virtue, but in a more ordinary sense) and tends to produce the disposition to suspend judgment...."[14] In other words, by eschewing beliefs (i.e., dogmas) one would live in accordance with virtue.

Prudence and virtue

Seneca, the Roman Stoic, said that perfect prudence is indistinguishable from perfect virtue. Thus, in considering all consequences, a prudent person would act in the same way as a virtuous person. The same rationale was expressed by Plato in Protagoras, when he wrote that people only act in ways that they perceive will bring them maximum good. It is the lack of wisdom that results in the making of a bad choice instead of a prudent one. In this way, wisdom is the central part of virtue. Plato realized that because virtue was synonymous with wisdom it could be taught, a possibility he had earlier discounted. He then added "correct belief" as an alternative to knowledge, proposing that knowledge is merely correct belief that has been thought through and "tethered".

Roman virtues

The term "virtue" itself is derived from the Latin "virtus" (the personification of which was the deity Virtus), and had connotations of "manliness", "honour", worthiness of deferential respect, and civic duty as both citizen and soldier. This virtue was but one of many virtues which Romans of good character were expected to exemplify and pass on through the generations, as part of the Mos Maiorum; ancestral traditions which defined "Roman-ness". Romans distinguished between the spheres of private and public life, and thus, virtues were also divided between those considered to be in the realm of private family life (as lived and taught by the paterfamilias), and those expected of an upstanding Roman citizen.

Most Roman concepts of virtue were also personified as a numinous deity. The primary Roman virtues, both public and private, were:

- Abundantia: "Abundance, Plenty" The ideal of there being enough food and prosperity for all segments of society. A public virtue.

- Auctoritas – "spiritual authority" – the sense of one's social standing, built up through experience, Pietas, and Industria. This was considered to be essential for a magistrate's ability to enforce law and order.

- Comitas – "humour" – ease of manner, courtesy, openness, and friendliness.

- Constantia – "perseverance" – military stamina, as well as general mental and physical endurance in the face of hardship.

- Clementia – "mercy" – mildness and gentleness, and the ability to set aside previous transgressions.

- Dignitas – "dignity" – a sense of self-worth, personal self-respect and self-esteem.

- Disciplina – "discipline" – considered essential to military excellence; also connotes adherence to the legal system, and upholding the duties of citizenship.

- Fides - "good faith" - mutual trust and reciprocal dealings in both government and commerce (public affairs), a breach meant legal and religious consequences.

- Firmitas – "tenacity" – strength of mind, and the ability to stick to one's purpose at hand without wavering.

- Frugalitas – "frugality" – economy and simplicity in lifestyle, want for what we must have and not what we need, regardless of one's material possessions, authority or wants one has, an individual always has a degree of honour. Frugality is to eschew what has no practical use if it is in disuse and if it comes at the expense of the other virtues.

- Gravitas – "gravity" – a sense of the importance of the matter at hand; responsibility, and being earnest.

- Honestas – "respectability" – the image and honor that one presents as a respectable member of society.

- Humanitas – "humanity" – refinement, civilization, learning, and generally being cultured.

- Industria – "industriousness" – hard work.

- Innocencia - "selfless" - Roman charity, always give without expectation of recognition, always give while expecting no personal gain, incorruptibility is aversion towards placing all power and influence from public office to increase personal gain in order to enjoy our personal or public life and deprive our community of their health, dignity and our sense of morality, that is an affront to every Roman.

- Laetitia - "Joy, Gladness" - The celebration of thanksgiving, often of the resolution of crisis, a public virtue.

- Nobilitas - "Nobility" - Man of fine appearance, deserving of honor, highly esteemed social rank, and, or, nobility of birth, a public virtue.

- Justitia – "justice" – sense of moral worth to an action; personified by the goddess Iustitia, the Roman counterpart to the Greek Themis.

- Pietas – "dutifulness" – more than religious piety; a respect for the natural order: socially, politically, and religiously. Includes ideas of patriotism, fulfillment of pious obligation to the gods, and honoring other human beings, especially in terms of the patron and client relationship, considered essential to an orderly society.

- Prudentia – "prudence" – foresight, wisdom, and personal discretion.

- Salubritas – "wholesomeness" – general health and cleanliness, personified in the deity Salus.

- Severitas – "sternness" – self-control, considered to be tied directly to the virtue of gravitas.

- Veritas – "truthfulness" – honesty in dealing with others, personified by the goddess Veritas. Veritas, being the mother of Virtus, was considered the root of all virtue; a person living an honest life was bound to be virtuous.

- Virtus – "manliness" – valor, excellence, courage, character, and worth. 'Vir' is Latin for "man".

The Seven Heavenly Virtues

In 410 CE, Aurelius Prudentius Clemens listed seven "heavenly virtues" in his book Psychomachia (Battle of Souls) which is an allegorical story of conflict between vices and virtues. The virtues depicted were:

- chastity

- temperance

- charity

- diligence

- patience

- kindness

- humility.[15]

Chivalric virtues in medieval Europe

In the 8th Century, upon the occasion of his coronation as Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne published a list of knightly virtues:

- Love God

- Love your neighbour

- Give alms to the poor

- Entertain strangers

- Visit the sick

- Be merciful to prisoners

- Do ill to no man, nor consent unto such

- Forgive as ye hope to be forgiven

- Redeem the captive

- Help the oppressed

- Defend the cause of the widow and orphan

- Render righteous judgement

- Do not consent to any wrong

- Persevere not in wrath

- Shun excess in eating and drinking

- Be humble and kind

- Serve your liege lord faithfully

- Do not steal

- Do not perjure yourself, nor let others do so

- Envy, hatred and violence separate men from the Kingdom of God

- Defend the Church and promote her cause.[16]

Religious traditions

Bahá'í faith

In the Bahá'í Faith, virtues are direct spiritual qualities that the human soul possesses, inherited from the world of God. The development and manifestation of these virtues is the theme of the Hidden Words of Bahá'u'lláh and are discussed in great detail as the underpinnings of a divinely-inspired society by `Abdu'l-Bahá in such texts as The Secret of Divine Civilization.

Buddhism

Buddhist practice as outlined in the Noble Eightfold Path can be regarded as a progressive list of virtues.

- Right View - Realizing the Four Noble Truths (samyag-vyāyāma, sammā-vāyāma).

- Right Mindfulness - Mental ability to see things for what they are with clear consciousness (samyak-smṛti, sammā-sati).

- Right Concentration - Wholesome one-pointedness of mind (samyak-samādhi, sammā-samādhi).

Buddhism's four brahmavihara ("Divine States") can be more properly regarded as virtues in the European sense. They are:

- Metta/Maitri: loving-kindness towards all; the hope that a person will be well; loving kindness is the wish that all sentient beings, without any exception, be happy.[17]

- Karuṇā: compassion; the hope that a person's sufferings will diminish; compassion is the wish for all sentient beings to be free from suffering.[17]

- Mudita: altruistic joy in the accomplishments of a person, oneself or other; sympathetic joy is the wholesome attitude of rejoicing in the happiness and virtues of all sentient beings.[17]

- Upekkha/Upeksha: equanimity, or learning to accept both loss and gain, praise and blame, success and failure with detachment, equally, for oneself and for others. Equanimity means not to distinguish between friend, enemy or stranger, but to regard every sentient being as equal. It is a clear-minded tranquil state of mind - not being overpowered by delusions, mental dullness or agitation.[18]

There are also the Paramitas ("perfections"), which are the culmination of having acquired certain virtues. In Theravada Buddhism's canonical Buddhavamsa[19] there are Ten Perfections (dasa pāramiyo). In Mahayana Buddhism, the Lotus Sutra (Saddharmapundarika), there are Six Perfections; while in the Ten Stages (Dasabhumika) Sutra, four more Paramitas are listed.

Christianity

.jpg)

In Christianity, the three theological virtues are faith, hope and love, a list which comes from 1 Corinthians 13:13 (νυνὶ δὲ μένει πίστις pistis (faith), ἐλπίς elpis (hope), ἀγάπη agape (love), τὰ τρία ταῦτα· μείζων δὲ τούτων ἡ ἀγάπη). The same chapter describes love as the greatest of the three, and further defines love as "patient, kind, not envious, boastful, arrogant, or rude." (The Christian virtue of love is sometimes called charity and at other times a Greek word agape is used to contrast the love of God and the love of humankind from other types of love such as friendship or physical affection.)

Christian scholars frequently add the four Greek cardinal virtues (prudence, justice, temperance, and courage) to the theological virtues to give the seven virtues; for example, these seven are the ones described in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, sections 1803–1829.

The Bible mentions additional virtues, such as in the "Fruit of the Holy Spirit," found in Galatians 5:22-23: "By contrast, the fruit of the Spirit it is benevolent-love: joy, peace, longsuffering, kindness, benevolence, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. There is absolutely no law against such a thing."[20]

The medieval and renaissance periods saw a number of models of sin listing the seven deadly sins and the virtues opposed to each.

| (Sin) | Latin | Virtue | (Latin) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pride | Superbia | Humility | Humilitas |

| Envy | Invidia | Kindness | Benevolentia |

| Gluttony | Gula | Temperance | Temperantia |

| Lust | Luxuria | Chastity | Castitas |

| Wrath | Ira | Patience | Patientia |

| Greed | Avaritia | Charity | Caritas |

| Sloth | Acedia | Diligence | Industria |

Daoism

"Virtue", translated from Chinese de (德), is also an important concept in Chinese philosophy, particularly Daoism. De (Chinese: 德; pinyin: dé; Wade–Giles: te) originally meant normative "virtue" in the sense of "personal character; inner strength; integrity", but semantically changed to moral "virtue; kindness; morality". Note the semantic parallel for English virtue, with an archaic meaning of "inner potency; divine power" (as in "by virtue of") and a modern one of "moral excellence; goodness".

In early periods of Confucianism, moral manifestations of "virtue" include ren ("humanity"), xiao ("filial piety"), and li ("proper behavior, performance of rituals"). The notion of ren - according to Simon Leys - means "humanity" and "goodness". Ren originally had the archaic meaning in the Confucian Book of Poems of "virility", but progressively took on shades of ethical meaning.[21] Some scholars consider the virtues identified in early Confucianism as non-theistic philosophy.[22]

The Daoist concept of De, compared to Confucianism, is more subtle, pertaining to the "virtue" or ability that an individual realizes by following the Dao ("the Way"). One important normative value in much of Chinese thinking is that one's social status should result from the amount of virtue that one demonstrates, rather than from one's birth. In the Analects, Confucius explains de as follows: "He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it."[23] In later periods, particularly from the Tang dynasty period, Confucianism as practiced, absorbed and melded its own concepts of virtues with those from Daoism and Buddhism.[22]

Hinduism

Virtue is a much debated[24] and an evolving concept in ancient scriptures of Hinduism.[25][26] The essence, need and value of virtue is explained in Hindu philosophy as something that cannot be imposed, but something that is realized and voluntarily lived up to by each individual. For example, Apastamba explained it thus: "virtue and vice do not go about saying - here we are!; neither the Gods, Gandharvas, nor ancestors can convince us - this is right, this is wrong; virtue is an elusive concept, it demands careful and sustained reflection by every man and woman before it can become part of one's life.[27]

Virtues lead to punya (Sanskrit: पुण्य,[28] holy living) in Hindu literature; while vices lead to pap (Sanskrit: पाप,[29] sin). Sometimes, the word punya is used interchangeably with virtue.[30]

The virtues that constitute a dharmic life - that is a moral, ethical, virtuous life - evolve in vedas and upanishads. Over time, new virtues were conceptualized and added by ancient Hindu scholars, some replaced, others merged. For example, Manusamhita initially listed ten virtues necessary for a human being to live a dharmic life: Dhriti (courage), Kshama (forgiveness), Dama (temperance), Asteya (Non-covetousness/Non-stealing), Saucha (inner purity), Indriyani-graha (control of senses), dhi (reflective prudence), vidya (wisdom), satyam (truthfulness), akrodha (freedom from anger).[31] In later verses, this list was reduced to five virtues by the same scholar, by merging and creating a more broader concept. The shorter list of virtues became: Ahimsa (Non-violence), Dama (self restraint), Asteya (Non-covetousness/Non-stealing), Saucha (inner purity), Satyam (truthfulness).[32][33]

The Bhagavad Gita - considered one of the epitomes of historic Hindu discussion of virtues and an allegorical debate on what is right and what is wrong - argues some virtues are not necessarily always absolute, but sometimes relational; for example, it explains a virtue such as Ahimsa must be re-examined when one is faced with war or violence from the aggressiveness, immaturity or ignorance of others.[34][35][36]

Islam

In Islam, the Quran is believed to be the literal word of God, and the definitive description of virtue while Muhammad is considered an ideal example of virtue in human form. The foundation of Islamic understanding of virtue was the understanding and interpretation of the Quran and the practices of Muhammad. Its meaning has always been in context of active submission to God performed by the community in unison. The motive force is the notion that believers are to "enjoin that which is virtuous and forbid that which is vicious" (al-amr bi-l-maʿrūf wa-n-nahy ʿani-l-munkar) in all spheres of life (Quran 3:110). Another key factor is the belief that mankind has been granted the faculty to discern God's will and to abide by it. This faculty most crucially involves reflecting over the meaning of existence. Therefore, regardless of their environment, humans are believed to have a moral responsibility to submit to God's will. Muhammad's preaching produced a "radical change in moral values based on the sanctions of the new religion and the present religion, and fear of God and of the Last Judgment". Later Muslim scholars expanded the religious ethics of the scriptures in immense detail.[37]

In the Hadith (Islamic traditions), it is reported by An-Nawwas bin Sam'an:

"The Prophet Muhammad said, "Virtue is good manner, and sin is that which creates doubt and you do not like people to know it.""

Wabisah bin Ma’bad reported:

“I went to Messenger of God and he asked me: “Have you come to inquire about virtue?” I replied in the affirmative. Then he said: “Ask your heart regarding it. Virtue is that which contents the soul and comforts the heart, and sin is that which causes doubts and perturbs the heart, even if people pronounce it lawful and give you verdicts on such matters again and again.”

— Ahmad and Ad-Darmi

Virtue, as seen in opposition to sin, is termed thawāb (spiritual merit or reward) but there are other Islamic terms to describe virtue such as faḍl ("bounty"), taqwa ("piety") and ṣalāḥ ("righteousness"). For Muslims fulfilling the rights of others are valued as an important building block of Islam. According to Muslim beliefs, God will forgive individual sins but the bad treatment of people and injustice with others will only be pardoned by them and not by God.

Jainism

In Jainism, attainment of enlightenment is possible only if the seeker possesses certain virtues. All Jains are supposed to take up the five vows of ahimsa (non violence), satya (truthfulness), asteya (non stealing), aparigraha (non attachment) and brahmacharya (celibacy) before becoming a monk. These vows are laid down by the Tirthankaras. Other virtues which are supposed to be followed by both monks as well as laypersons include forgiveness, humility, self-restraint and straightforwardness. These vows assists the seeker to escape from the karmic bondages thereby escaping the cycle of birth and death to attain liberation.[38]

Judaism

Loving God and obeying his laws, in particular the Ten Commandments, are central to Jewish conceptions of virtue. Wisdom is personified in the first eight chapters of the Book of Proverbs and is not only the source of virtue but is depicted as the first and best creation of God (Proverbs 8:12-31).

A classic articulation of the Golden Rule came from the first century Rabbi Hillel the Elder. Renowned in the Jewish tradition as a sage and a scholar, he is associated with the development of the Mishnah and the Talmud and, as such, one of the most important figures in Jewish history. Asked for a summary of the Jewish religion in the most concise terms, Hillel replied (reputedly while standing on one leg): "That which is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow. That is the whole Torah. The rest is commentary; go and learn."[39]

Philosophers' views

Valluvar

While religious scriptures generally consider dharma or aṟam (the Tamil term for virtue) as a divine virtue, Valluvar describes it as a way of life rather than any spiritual observance, a way of harmonious living that leads to universal happiness.[40] For this reason, Valluvar keeps aṟam as the cornerstone throughout the writing of the Kural literature.[41] Valluvar considered justice as a facet or product of aram.[40] While ancient Greek philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, and their descendants opined that justice cannot be defined and that it was a divine mystery, Valluvar positively suggested that a divine origin is not required to define the concept of justice.[40] In the words of V. R. Nedunchezhiyan, justice according to Valluvar "dwells in the minds of those who have knowledge of the standard of right and wrong; so too deceit dwells in the minds which breed fraud."[40]

René Descartes

For the Rationalist philosopher René Descartes, virtue consists in the correct reasoning that should guide our actions. Men should seek the sovereign good that Descartes, following Zeno, identifies with virtue, as this produces a solid blessedness or pleasure. For Epicurus the sovereign good was pleasure, and Descartes says that in fact this is not in contradiction with Zeno's teaching, because virtue produces a spiritual pleasure, that is better than bodily pleasure. Regarding Aristotle's opinion that happiness depends on the goods of fortune, Descartes does not deny that these goods contribute to happiness, but remarks that they are in great proportion outside one's own control, whereas one's mind is under one's complete control.[42]

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant, in his Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime, expresses true virtue as different from what commonly is known about this moral trait. In Kant's view, to be goodhearted, benevolent and sympathetic is not regarded as true virtue. The only aspect that makes a human truly virtuous is to behave in accordance with moral principles. Kant presents an example for more clarification; suppose that you come across a needy person in the street; if your sympathy leads you to help that person, your response does not illustrate your virtue. In this example, since you do not afford helping all needy ones, you have behaved unjustly, and it is out of the domain of principles and true virtue. Kant applies the approach of four temperaments to distinguish truly virtuous people. According to Kant, among all people with diverse temperaments, a person with melancholy frame of mind is the most virtuous whose thoughts, words and deeds are one of principles.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche's view of virtue is based on the idea of an order of rank among people. For Nietzsche, the virtues of the strong are seen as vices by the weak and slavish, thus Nietzsche's virtue ethics is based on his distinction between master morality and slave morality. Nietzsche promotes the virtues of those he calls "higher men", people like Goethe and Beethoven. The virtues he praises in them are their creative powers (“the men of great creativity” - “the really great men according to my understanding” (WP 957)). According to Nietzsche these higher types are solitary, pursue a "unifying project", revere themselves and are healthy and life-affirming.[43] Because mixing with the herd makes one base, the higher type “strives instinctively for a citadel and a secrecy where he is saved from the crowd, the many, the great majority…” (BGE 26). The 'Higher type' also "instinctively seeks heavy responsibilities" (WP 944) in the form of an "organizing idea" for their life, which drives them to artistic and creative work and gives them psychological health and strength.[43] The fact that the higher types are "healthy" for Nietzsche does not refer to physical health as much as a psychological resilience and fortitude. Finally, a Higher type affirms life because he is willing to accept the eternal return of his life and affirm this forever and unconditionally.

In the last section of Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche outlines his thoughts on the noble virtues and places solitude as one of the highest virtues:

And to keep control over your four virtues: courage, insight, sympathy, solitude. Because solitude is a virtue for us, since it is a sublime inclination and impulse to cleanliness which shows that contact between people (“society”) inevitably makes things unclean. Somewhere, sometime, every community makes people – “base.” (BGE §284)

Nietzsche also sees truthfulness as a virtue:

Genuine honesty, assuming that this is our virtue and we cannot get rid of it, we free spirits – well then, we will want to work on it with all the love and malice at our disposal and not get tired of ‘perfecting’ ourselves in our virtue, the only one we have left: may its glory come to rest like a gilded, blue evening glow of mockery over this aging culture and its dull and dismal seriousness! (Beyond Good and Evil, §227)

Benjamin Franklin

These are the virtues[44] that Benjamin Franklin used to develop what he called 'moral perfection'. He had a checklist in a notebook to measure each day how he lived up to his virtues.

They became known through Benjamin Franklin's autobiography.

- Temperance: Eat not to Dullness. Drink not to Elevation.

- Silence: Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself. Avoid trifling Conversation.

- Order: Let all your Things have their Places. Let each Part of your Business have its Time.

- Resolution: Resolve to perform what you ought. Perform without fail what you resolve.

- Frugality: Make no Expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e. Waste nothing.

- Industry: Lose no Time. Be always employed in something useful. Cut off all unnecessary Actions.

- Sincerity: Use no hurtful Deceit. Think innocently and justly; and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

- Justice: Wrong none, by doing Injuries or omitting the Benefits that are your Duty.

- Moderation: Avoid Extremes. Forbear resenting Injuries so much as you think they deserve.

- Cleanliness: Tolerate no Uncleanness in Body, Clothes or Habitation.

- Tranquility: Be not disturbed at Trifles, or at Accidents common or unavoidable.

- Chastity: Rarely use Venery but for Health or Offspring; Never to Dullness, Weakness, or the Injury of your own or another's Peace or Reputation.

- Humility: Imitate Jesus and Socrates.

Contemporary views

Virtues as emotions

Marc Jackson in his book Emotion and Psyche puts forward a new development of the virtues. He identifies the virtues as what he calls the good emotions "The first group consisting of love, kindness, joy, faith, awe and pity is good"[45] These virtues differ from older accounts of the virtues because they are not character traits expressed by action, but emotions that are to be felt and developed by feeling not acting.

In Objectivism

Ayn Rand held that her morality, the morality of reason, contained a single axiom: existence exists, and a single choice: to live. All values and virtues proceed from these. To live, man must hold three fundamental values that one develops and achieves in life: Reason, Purpose, and Self-Esteem. A value is "that which one acts to gain and/or keep ... and the virtue[s] [are] the act[ions] by which one gains and/or keeps it." The primary virtue in Objectivist ethics is rationality, which as Rand meant it is "the recognition and acceptance of reason as one's only source of knowledge, one's only judge of values and one's only guide to action."[46] These values are achieved by passionate and consistent action and the virtues are the policies for achieving those fundamental values.[47] Ayn Rand describes seven virtues: rationality, productiveness, pride, independence, integrity, honesty and justice. The first three represent the three primary virtues that correspond to the three fundamental values, whereas the final four are derived from the virtue of rationality. She claims that virtue is not an end in itself, that virtue is not its own reward nor sacrificial fodder for the reward of evil, that life is the reward of virtue and happiness is the goal and the reward of life. Man has a single basic choice: to think or not, and that is the gauge of his virtue. Moral perfection is an unbreached rationality, not the degree of your intelligence but the full and relentless use of your mind, not the extent of your knowledge but the acceptance of reason as an absolute.[48]

In modern psychology

Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman, two leading researchers in positive psychology, recognizing the deficiency inherent in psychology's tendency to focus on dysfunction rather than on what makes a healthy and stable personality, set out to develop a list of "Character Strengths and Virtues".[49] After three years of study, 24 traits (classified into six broad areas of virtue) were identified, having "a surprising amount of similarity across cultures and strongly indicat[ing] a historical and cross-cultural convergence."[50] These six categories of virtue are courage, justice, humanity, temperance, transcendence, and wisdom.[51] Some psychologists suggest that these virtues are adequately grouped into fewer categories; for example, the same 24 traits have been grouped into simply: Cognitive Strengths, Temperance Strengths, and Social Strengths.[52]

Vice as opposite

The opposite of a virtue is a vice. Vice is a habitual, repeated practice of wrongdoing. One way of organizing the vices is as the corruption of the virtues.

As Aristotle noted, however, the virtues can have several opposites. Virtues can be considered the mean between two extremes, as the Latin maxim dictates in medio stat virtus - in the centre lies virtue. For instance, both cowardice and rashness are opposites of courage; contrary to prudence are both over-caution and insufficient caution; the opposites of pride (a virtue) are undue humility and excessive vanity. A more "modern" virtue, tolerance, can be considered the mean between the two extremes of narrow-mindedness on the one hand and over-acceptance on the other. Vices can therefore be identified as the opposites of virtues - but with the caveat that each virtue could have many different opposites, all distinct from each other.

See also

- Arete

- Aretology

- Bushido

- Catalogue of Vices and Virtues

- Chastity

- Chivalry

- Civic virtue

- Common good

- Consequentialism

- Epistemic virtue

- Evolution of morality

- Five Virtues (Sikh)

- Hospitium

- Humanity (virtue)

- Ideal (ethics)

- Intellectual virtues

- Knightly Virtues

- List of virtues

- "Mature" defence mechanisms

- Moral character

- Nonviolence

- Paideia

- Phronesis

- Psychological foresight

- Prussian virtues

- Nine Noble Virtues (Asatru and Odinism)

- Seven Deadly Sins

- Seven Heavenly Virtues

- Teachings of the Seven Grandfathers

- Three Jewels of the Tao

- Three theological virtues

- Tree of virtues

- Value theory

- Vice

- Virtus (deity)

- Virtue ethics

- Virtue name

- Wisdom

References

- Jon Wetlesen, Did Santideva Destroy the Bodhisattva Path? Jnl Buddhist Ethics, Vol. 9, 2002 Archived 2007-02-28 at the Wayback Machine (accessed March 2010)

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu. Abhidhammattha Sangaha: A Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma. BPS Pariyatti Editions, 2000, p. 89.

- ’’The Merriam-Webster New Book of Word Histories’’. Merriam-Webster Inc., 1991. p. 496

- Karenga, M. (2004), Maat, the moral ideal in ancient Egypt: A study in classical African ethics, Routledge

- Norman Rufus Colin Cohn (1993). Cosmos, Caos and the World to Come: The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith. ISBN 978-0-300-05598-6.

- Jan Assmann, Translated by Rodney Livingstone, Religion and Cultural Memory: Ten Studies, Stanford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8047-4523-4

- Stanley B. Cunningham (2002), Review of Virtues and Vices and Other Essays in Moral Philosophy, Dialogue, Volume 21, Issue 01, March 1982, pp. 133–37

- Den Uyl, D. J. (1991), The virtue of prudence, P. Lang., in Studies in Moral Philosophy. Vol. 5 General Editor: John Kekes

- Carr, D. (1988), The cardinal virtues and Plato's moral psychologym The Philosophical Quarterly, 38(151), pp. 186–200

- Gregory Vlastos, The Unity of the Virtues in the "Protagoras", The Review of Metaphysics, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Mar., 1972), pages 415-458

- Aristotle. "Sparknotes.com". Sparknotes.com. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- "Nicomachean Ethics". Home.wlu.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- "Philodemus' Method of Studying and Cultivating the Virtues". Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Sextus Empiricus Outlines of Pyrrhonism Book I Chapter 8 Sections 16-17.

- "Prudentius Seven Heavenly Virtues". Changing Minds. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "The origins of Chivalry". Baronage. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "Buddhist Studies for Secondary Students, Unit 6: The Four Immeasurables". Buddhanet.net. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- "A View on Buddhism, The four immeasurables: Love, Compassion, Joy and Equanimity". Archived from the original on 2006-08-19. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- Buddhavamsa, chapter 2. For an on-line reference to the Buddhavamsa's seminality in the Theravada notion of parami, see Bodhi (2005).

In terms of other examples in the Pali literature, Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), p. 454, entry for "Pāramī," (retrieved 2007-06-24) cites Jataka i.73 and Dhammapada Atthakatha i.84. Bodhi (2005) also mentions Acariya Dhammapala's treatise in the Cariyapitaka-Atthakatha and the Brahmajala Sutta subcommentary (tika). - Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland, Matthew Black, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger and Allen Wikgren, The Greek New Testament, 4th ed. (Federal Republic of Germany: United Bible Societies, 1993, c1979)

- Lin Yu-sheng: "The evolution of the pre-Confucian meaning of jen and the Confucian concept of moral autonomy," Monumenta Serica, vol.31, 1974-75

- Yang, C. K. (1971), Religion in Chinese society: a study of contemporary social functions of religion and some of their historical factors, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-88133-621-4

- Lunyu 2/1 Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, tr. James Legge

- Roderick Hindery (2004), Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions, ISBN 978-8120808669; pages 268-72;

- Quote: "(In Hinduism), srutis did not pretend to deal with all situations or irregularities in the moral life, leaving these matters to human reasons (Mbh Xii.109); Accordingly, that again which is virtue may, according to time and place, be sin (...); Under certain conditions, acts that are apparently evil (such as violence) can be permitted if they produce consequences that are good (protection of children and women in self-defense when the society is attacked in war)

- Quote: "(The Hindu scripture) notes the interrelationship of several virtues, consequentially. Anger springs from covetousness; (the vice of) envy disappears in consequence of (the virtues) of compassion and knowledge of self (Mbh Xii.163);

- Crawford, S. Cromwell (1982), The evolution of Hindu ethical ideals, Asian Studies Program, University of Hawaii Press

- Becker and Becker (2001), Encyclopedia of Ethics, ISBN 978-0415936729, 2nd Edition, Routledge, pages 845-848

- Phillip Wagoner, see Foreword, in Srinivasan, Dharma: Hindu Approach to a Purposeful Life, ISBN 978-1-62209-672-5;

- Also see: Apastamba, Dharma Sutra, 1.20.6

- puNya Spoken Sanskrit English Dictionary, Germany (2010)

- search for pApa Monier-Williams' Sanskrit-English Dictionary, University of Koeln, Germany (2008)

- What Is Hinduism?, Himalayan Academy (2007), ISBN 978-1-934145-00-5, page 377

- Tiwari, K. N. (1998), Classical Indian Ethical Thought: A Philosophical Study of Hindu, Jaina, and Buddhist Morals, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 978-81-208-1608-4, pp 52-55

- Gupta, B. (2006). BHAGAVAD GĪTĀ AS DUTY AND VIRTUE ETHICS. Journal of Religious Ethics, 34(3), 373-395.

- Mohapatra & Mohapatra, Hinduism: Analytical Study, ISBN 978-8170993889; see pages 37-40

- Subedi, S. P. (2003). The Concept in Hinduism of ‘Just War’. Journal of Conflict and Security Law, 8(2), pages 339-361

- Klaus K. Klostermaier (1996), in Harvey Leonard Dyck and Peter Brock (Ed), The Pacifist Impulse in Historical Perspective, see Chapter on Himsa and Ahimsa Traditions in Hinduism, ISBN 978-0802007773, University of Toronto Press, pages 230-234

- Bakker, F. L. (2013), Comparing the Golden Rule in Hindu and Christian Religious Texts. Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses, 42(1), pages 38-58

- Bearman et al. 2009, Akhlaq

- https://medium.com/bliss-of-wisdom/जैन-धर्म-के-पाँच-मूलभूत-सिद्धांत-bfc9b756d509

- Babylonian Talmud, tractate Shabbat 31a. See also the ethic of reciprocity or "The Golden rule."

- N. Sanjeevi (1973). First All India Tirukkural Seminar Papers (2nd ed.). Chennai: University of Madras. p. xxiii–xxvii.

- N. Velusamy and Moses Michael Faraday (Eds.) (February 2017). Why Should Thirukkural Be Declared the National Book of India? (in Tamil and English) (First ed.). Chennai: Unique Media Integrators. p. 55. ISBN 978-93-85471-70-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Blom, John J., Descartes. His moral philosophy and psychology. New York University Press. 1978. ISBN 0-8147-0999-0

- Leiter, Brian. "Nietzsche's Moral and Political Philosophy". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- Franklin's 13 Virtues Extract of Franklin's autobiography, compiled by Paul Ford.

- Marc Jackson (2010) Emotion and Psyche. O-books. p. 12 (ISBN 978-1-84694-378-2)

- Rand, Ayn The Virtue of Selfishness: A New Concept of Egoism, p. 27

- Gotthelf, Allan On Ayn Rand; p. 86

- Rand, Ayn (1961) For the New Intellectual Galt’s Speech, "For the New Intellectual: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand", pp. 131, 178.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M.E.P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford University Press. (ISBN 0-19-516701-5)

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M.E.P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford University Press. p. 36. (ISBN 0-19-516701-5)

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M.E.P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford University Press. pp. 36-39. (ISBN 0-19-516701-5)

- Jessica Shryack, Michael F. Steger, Robert F. Krueger, Christopher S. Kallie. 2010. The structure of virtue: An empirical investigation of the dimensionality of the virtues in action inventory of strengths. Elsevier.

Further reading

- Newton, John, Ph.D. Complete Conduct Principles for the 21st Century, 2000. ISBN 0967370574.

- Hein, David. "Christianity and Honor." The Living Church, August 18, 2013, pp. 8–10.

- Den Uyl, Douglas (2008). "Virtue". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 521–22. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n318. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

External links

- The Wikiversity course on virtues

- The Large Clickable List of Virtues at VirtueScience.com

- An overview of Aristotle's ethics, including an explanation and chart of virtues

- Virtue Epistemology

- Virtue, a Catholic perspective

- Virtue, a Buddhist perspective

- Greek Virtue (quotations)

- Peterson & Seligman findings on virtues and strengths (landmark psychological study)

- Illustrated account of the images of the Virtues in the Thomas Jefferson Building, Library of Congress, Washington DC

- The Science of Virtues Project at the University of Chicago

- Roman virtues

- "Virtue", BBC Radio 4 discussion with Galen Strawson, Miranda Fricker and Roger Crisp (In Our Time, Feb. 28, 2002)