Christianity and animal rights

The relationship between Christianity and animal rights is complex, with different Christian communities coming to different conclusions about the status of animals. The topic is closely related to, but broader than, the practices of Christian vegetarians and the various Christian environmentalist movements.

Many Christian philosophers and socio-political figures have stated that Christians should follow the example of Jesus and treat animals in a way that expresses compassion and demonstrates the respectful stewardship of humanity over the environment. William Wilberforce, a co-founder of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, is an example. Large organizations in which a variety of different groups work together, such as the Humane Society of the United States, have undertaken religious outreach using such arguments.[1]

Andrew Linzey has pointed out it would be wrong to see Christianity as an inherent enemy of animal rights since Christian theology, like all other religious traditions, has some unique insights to viewing animal life as having fundamental value.[2] Throughout history, there have been Christian thinkers who have raised tough ethical questions about the moral status of animals.[3] Francis of Assisi is perhaps the most well-known example.

Various church founders have recommended vegetarianism for ethical reasons, such as William Cowherd from the Bible Christian Church,[4] Ellen G. White from the Seventh-day Adventists[5] and John Wesley, the founder of Methodism.[6] Cowherd helped to establish the world's first Vegetarian Society in 1847.[7] Wesley's vegetarian views inspired a later generation to establish the American Vegetarian Society in 1850.[6] Christian denominations like Seventh Day Adventists have central vegetarian doctrines incorporated.[8]

The rise of Christianity put an end to animal sacrificing,[9] and that the Christian hope involves the idea of the Peaceable Kingdom found in the Hebrew Bible, which looks to a peaceful coexistence of animals such as wolves and lambs.[10]

Background and details

Biblical context

The Bible offers a mixed bag when it comes to support that it might offer for the concept of animal rights. This is seen in the first chapters of Genesis. On the one hand, Genesis 1:26-28 says that humans, having been made in the image of God, are to have dominion over the non-human animals. Peter Singer believes that this has been used by many Christian theologians throughout Church history to justify the idea that non-human animals exist only to serve or be of use to humans, which has sadly led to much use and abuse of animals at the hands of humanity.[11] On the other hand, many Christian theologians, especially in recent times, are suggesting that a more accurate reading of Genesis 1:26-28 requires reading it in light of Genesis 1:29-30, which teaches that all of God's creatures were initially given a plant-based diet:

God said, "See, I have given you every plant yielding seed that is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit; you shall have them for food. And to every beast of the earth, and to every bird of the air, and to everything that creeps on the earth, everything that has the breath of life, I have given every green plant for food." And it was so.

This leads to the recognition that, whatever 'dominion' means, it must be compatible with the idea of not eating any animals.[12] This suggests that 'dominion' be understood in terms of 'looking after', 'ruling over', 'being responsible for', or 'guiding',[13] and indeed, some English Bible translations, such as the NIV, NLT and Message, use such terms in place of the older language of 'dominion'.

Moreover, in the Genesis account, each stage of creation is pronounced 'good' by God, with the whole being pronounced 'very good'. This suggests that God values everything he has made, including all of its creatures. As Andrew Linzey says, this provides the basis for a very positive view of animals and their worth.[2]

Other passages which present a positive view of animals, and imply that humanity's attitude towards them should be one of caring responsibility, include:

- Exodus 23:4-12 which instructs the Israelites to care for any oxen and donkey they come across belonging to their enemies.

- Psalm 104:31 affirms that God rejoices in all his works, in everything he has created.

- Proverbs 12:10 which says that a "righteous man cares about his animal's health".

- Matthew 10:29 in which Jesus identifies sparrows as animals which are not valued by humans, but which God still knows and remembers.

- Matthew 23:37 which represents Jesus as comparing his love and care for Jerusalem and its inhabitants to the care a mother hen provides for her chicks.

There are, however, also passages which seem to condone the use of non-human animals in various ways, primarily in religious sacrifices and as food. More specifically, meat-eating and other forms of using some animals for human benefit receive an explicit approval by God in the aftermath of the events from the expulsion from Eden to the end of the global flood. A Genesis 9:3 (NIV) section states: "Just as I gave you the green plants, I now give you everything."[10]

The traditional biblical (especially Old Testament) viewpoint among Jews and Christians is that God distinguished man from animals, and gave man control over animals to benefit man, but also that God gave man moral guidelines to prevent cruelty to - or needless suffering by - animals.

In particular, animal sacrifice plays a major role in many sections of the Bible, reflective of the practice's widespread nature in early Judaism. Specific instances include Leviticus 1:2 (NIV): "Speak to the Israelites and say to them: 'When any of you brings an offering to the Lord, bring as your offering an animal from either the herd or the flock.'"[10] A consensus viewpoint doesn't exist as to the exact meaning and reasoning behind said sacrifices, even if they have been interpreted as perhaps symbolizing the returning to God the sense of the 'power over life' in reverential tribute to how God served as the maker of creation to begin with. As remarked by the theologian Andrew Linzey, "there's no one view of animal sacrifices even by those who practiced it."[2]

In terms of the afterlife and the world to come, descriptions of heaven describe an existence without violence and strife either among non-human animals or in their relationship to people. For example, Isaiah 65:25 (NIV) states: "The wolf and the lamb will feed together, and the lion will eat straw like the ox, but dust will be the serpent's food. They will neither harm nor destroy on all my holy mountain, says the Lord."[10] The depiction of how God's ideal new earth will look like can be interpreted as a signal that human beings should minimize violence as much as possible in terms of all animals.[2]

Jesus Christ in the New Testament exists not just as the core theological figure in Christian thought but also as a moral icon to look to as an inspiration in terms of Christian ethics. Looking at the canonical gospels, Jesus ate the Passover meal which included meat (e.g. Matthew 26:17-20). He did not identify being a vegetarian and did not act like one.[2] Biblical passages associate Jesus and his followers with fishing, which could be an implied support for meat-eating (at least of that type) specifically.[1] Jesus rode on a donkey (Mark 11:7, Matthew 21:4-7, John 12:14,15). In the larger context of animal rights, though, the association of Jesus as a 'good shepherd' character, one taking things so far that "the good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep", establishes a moral theme of those that are stronger and more powerful being willing to sacrifice for the weaker and less powerful, all out of love. This can be taken as inspiration for animal welfare advocacy by modern Christians.[2]

In the era of the apostles, eating meat is addressed as a normal activity. The first apostolic counsel told Christians to refrain from eating meat that had been strangled, but did not hinder the eating of other meat (Acts 15:29). Paul wrote to the Romans, in the context of freedom to make choices, "Whoever eats meat does so to the Lord, for they give thanks to God" (Romans 14:6), with no condemnation of this activity. Writing to the Christians in Corinth, he told them "Eat anything sold in the meat market" (1 Corinthians 10:25). Far from discouraging the eating of meat (except for matters of harmony and testimony), Paul wrote of vegetarians as those with weak faith, "One person's faith allows them to eat anything, but another, whose faith is weak, eats only vegetables" (Romans 14:2).

The teachings and rise of Christianity ended animal sacrifice, as Christians believe Jesus died for all the sins of humanity and is often portrayed as the last sacrificial lamb in the New Testament.[9]

Christian perspectives

Various church founders have recommended vegetarianism, such as William Cowherd from the Bible Christian Church and Ellen G. White from the Seventh-day Adventists.[4][5] Cowherd, who founded the Bible Christian Church in 1809, helped to establish the world's first Vegetarian Society in 1847.[7] John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, promoted vegetarianism which helped establish the American Vegetarian Society in 1850.[6]

Some Christians denominations such as the Seventh Day Adventists have central vegetarian doctrines that play a role in adherents.[8]

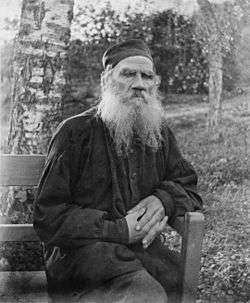

The tradition of Christian vegetarianism has long been a minority viewpoint among Christian communities, though its history has gone back many decades in religious thought. Leo Tolstoy's views, as expressed in things such as his famous 1909 essay about a slaughterhouse, have remained influential for years. Later writers that cite his comments on animal rights include Catholic columnist Mary Eberstadt.[1]

The Catechism of the Catholic Church takes the position that Christians are called to express kindness to the world's creatures in general, and people possess a moral obligation to avoid causing unnecessary suffering to animals. Meat-eating in the context of nourishment is permitted. Examples of Roman Catholic figures that have written in favor of animal rights and against factory farming, though not strictly being vegetarians themselves, include Fordham University professor Charles Camosy and the aforementioned columnist Mary Eberstadt. The former wrote the work For Love of Animals: Christian Ethics, Consistent Action on the subject, which the latter praised while writing for National Review.[1]

Opinions within the Church of England have drawn influence from the work of seminal Anglican theologian Andrew Linzey, who published Animal Rights: A Christian Assessment in 1976 while still a student. Labeled by The New York Times as having "caused a sensation in Christian circles" from his first book on,[1] he's a member of the faculty at the University of Oxford as well as the founder and director of the Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics, an independent academic organization.[14]

In 1992, Anglican figures arguing in support of taking a stance against animal cruelty succeeded in having forty-one bishops signing a pledge not to wear fur because of the suffering inflicted, with the pledge getting some attention. However, the debate undertaken by the General Synod in 1990 about both hunting and factory farming practices done on Church-owned land ended with said practices being allowed to go on.[2]

In terms of the Methodist tradition, figures such as University of Chester professor and author David Clough have held a respect for the rights of animals should exist given that, in Christian terms, God deliberately created the creatures of the world and proclaimed them all as good. He's written that how non-humans are "reconciled to God in Jesus Christ and will be redeemed by God in the new creation" accordingly creates duties for mankind. Besides serving as a Methodist pastor, he's President of the Society for the Study of Christian Ethics.[1][15]

Bands often labeled as being Christian metal or influenced by Christian music such as Blessthefall, MyChildren MyBride, Gwen Stacy, and Sleeping Giant have had members speak out in favor of animal rights, with those statements garnering attention from secular music-related publications.[16]

Secular responses and additional debate

Philosopher Peter Singer has argued in publications such as his seminal book Animal Liberation, first published in 1975, that Christian thought has contributed to animal cruelty and suffering. He cited commentary from figures such as Aquinas about humanity's innate right to control the natural world as holding back progress in animal rights. However, Singer later stated that he had changed his views in part given the complexity of different views towards animals among different Christians.[1]

The aforementioned Andrew Linzey commented in 1996 that:

[I]t’s right for animal rights people to be critical and judgmental of the Christian tradition... [which] has been amazingly callous towards animals. Christian theologians have been neglectful and dismissive of the cause of animals— and many still are. Christians and Jews have allowed their ancient texts— such as Genesis— to be read as licensing tyranny over animals... [and] animal rights people sometimes look on Christianity as though it was unambiguously "the enemy." I think it is wrong to write off Christianity in this way. All religious traditions have great resources for a very positive ethic in relation to animals. I would go further and say that however awful the record of Christianity has been, Christian theology has some unique insights fundamental to valuing animal life. From my perspective, without a sense of ultimate meaning and purpose, it is difficult, if not impossible, to justify any kind of moral endeavor... I’m one of those people who believe that morality really depends upon vision.[2]

Contemporary philosopher Bernard Rollin writes that "dominion does not entail or allow abuse any more than does dominion a parent enjoys over a child."[17] Rollin further states that the Biblical Sabbath requirement promulgated in the Ten Commandments "required that animals be granted a day of rest along with humans. Correlatively, the Bible forbids 'plowing with an ox and an ass together' (Deut. 22:10–11). According to the rabbinical tradition, this prohibition stems from the hardship that an ass would suffer by being compelled to keep up with an ox, which is, of course, far more powerful. Similarly, one finds the prohibition against 'muzzling an ox when it treads out the grain' (Deut. 25:4–5), and even an environmental prohibition against destroying trees when besieging a city (Deut. 20:19–20). These ancient regulations, "bespeak of an eloquent awareness of the status of animals as ends in themselves", a point also corroborated by Norm Phelps.[17][18]

See also

- Animal cruelty

- Animal liberation movement

- Animal protectionism

- Christian culture

- Christian ethics

- Christian vegetarianism

- Christianity and environmentalism

- Ethics of eating meat

- Islam and animal rights

- Good Shepherd

- Lamb of God

- Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics

References

- Oppenheimer, Mark (December 6, 2013). "Scholars Explore Christian Perspectives on Animal Rights". The New York Times. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- Berry, Rynn (February 1996). "Christianity and Animals: An Interview with Andrew Linzey". Satya. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- Linzey, Andrew (2009). Creatures of the Same God. Lantern Books. pp. 21–22.

- "The Bible Christian Church". International Vegetarian Union.

- Karen Iacobbo; Michael Iacobbo (2004). Vegetarian America: A History. p. 97.

- Null, Gary (1996). The Vegetarian Handbook. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 13. ISBN 0312144415.

- "History of Vegetarianism - Early Ideas". The Vegetarian Society. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2008-07-08.; Gregory, James (2007) Of Victorians and Vegetarians. London: I. B. Tauris pp. 30–35.

- Grant, George; Montenegro, Jose. "Vegetarianism in Seventh-day Adventism". Oxford Scholarship Online. Oxoford University.

- DeMello, Margo (18 September 2012). Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-Animal Studies. Columbia University Press. p. 317. ISBN 9780231526760.

Later, with the rise of Christianity, animal sacrifice ended. Instead, Christians believe that God sacrificed his son Jesus in order to give humankind salvation; this is one of the reasons that Jesus is often represented as a lamb in Christianity.

- Zavada, Jack. "Do Animals Have Souls?". About.com. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- Singer, Peter (2015). Animal Liberation: 40th Anniversary Edition. Open Road. p. 189ff.

- Withrow-King, Sarah (2016). Animals Are Not Ours: An Evangelical Animal Liberation Theology. Wipf and Stock. p. 18.

- Adams, Carol J. (2012). "1. What about Dominion in Genesis?". In York, Tripp; Alexis-Baker, Andy (eds.). A Faith Embracing All Creatures. p. 3.

- "Director - Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics". www.oxfordanimalethics.com.

- "Professor David Clough". University of Chester. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- "Christian Metal Bands Talk Animal Rights". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-11-13.

- Rollin, Bernard E. Animal Rights and Human Morality. Prometheus Books. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-61592-211-6.

- Phelps, Norm (2002). Animal Rights According to the Bible. Lantern Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-59056-009-9.

The Bible's most important reference to the sentience and will of nonhuman animals is found in Deuteronomy 25:4, which became the scriptural foundation of the rabbinical doctrine of tsar ba'ale chayim, "the suffering of the living," which makes relieving the suffering of animals a religious duty for Jews. "You shall not muzzle the ox while he is threshing." The point of muzzling the ox was to keep him from eating any of the grain that he was threshing. The point of the commandment was the cruelty of forcing an animal to work for hours at a time with his face only inches from delicious food while not allowing him to eat any of it.