Appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political or material concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict.[1] The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK Governments of Prime Ministers Ramsay MacDonald, Stanley Baldwin and most notably Neville Chamberlain towards Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy[2] between 1935–39.

At the beginning of the 1930s, such concessions were widely seen as positive due to the trauma of World War I, second thoughts about the vindictive treatment of Germany in the Treaty of Versailles, and a perception that fascism was a useful form of anti-communism. However, by the time of the Munich Pact—concluded on 30 September 1938 among Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy—the policy was opposed by the Labour Party, by a few Conservative dissenters such as future Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Secretary of State for War Duff Cooper, and future Prime Minister Anthony Eden. Appeasement was strongly supported by the British upper class, including: royalty, big business (based in the City of London), the House of Lords, and media such as the BBC and The Times.[3]

As alarm grew about the rise of fascism in Europe, Chamberlain resorted to news censorship to control public opinion.[4] He confidently announced after Munich that he had secured "peace for our time".[5]

The policies have been the subject of intense debate for more than seventy years among academics, politicians, and diplomats. The historians' assessments have ranged from condemnation for allowing Hitler's Germany to grow too strong, to the judgment that Germany was so strong that it might well win a war and that postponement of a showdown was in their country's best interests. Historian Andrew Roberts argued in 2019, "Indeed, it is the generally accepted view in Britain today that they were right at least to have tried... Britain would not enter hostilities for many more months, admitting unreadiness to directly oppose Germany in combat. She sat and watched the invasion of France, acting only four years later."[6]

Failure of collective security

– Walter Theimer (ed.), The Penguin Political Dictionary, 1939

Chamberlain's policy of appeasement emerged from the failure of the League of Nations and the failure of collective security. The League of Nations was set up in the aftermath of World War I in the hope that international cooperation and collective resistance to aggression might prevent another war. Members of the League were entitled to the assistance of other members if they came under attack. The policy of collective security ran in parallel with measures to achieve international disarmament and where possible was to be based on economic sanctions against an aggressor. It appeared to be ineffectual when confronted by the aggression of dictators, notably Germany's Remilitarization of the Rhineland, and Italian leader Benito Mussolini's invasion of Abyssinia.

Invasion of Manchuria

In September 1931, Japan, a member of the League of Nations, invaded Manchuria in northeast China, claiming that its population was not only Chinese but was a multi-ethnic region. China appealed to the League of Nations and the United States for assistance. The Council of the League asked the parties to withdraw to their original positions to permit a peaceful settlement. The United States reminded them of their duty under the Kellogg–Briand Pact to settle matters peacefully. Japan was undeterred and went on to occupy the whole of Manchuria. The League set up a commission of inquiry that condemned Japan, the League duly adopting the report in February 1933. In response, Japan resigned from the League and continued its advance into China; neither the League nor the United States took any action. However, the U.S. issued the Stimson Doctrine and refused to recognize Japan's conquest, which played a role in shifting U.S. policy to favour China over Japan in the late-1930s.[7] Some historians, such as David Thomson, assert that the League's "inactivity and ineffectualness in the Far East lent every encouragement to European aggressors who planned similar acts of defiance".[8]

Anglo-German Naval Agreement

In this 1935 pact, the UK permitted Germany to begin rebuilding its navy, including its U-boats, in spite of Hitler already having violated the Treaty of Versailles.

Abyssinia crisis

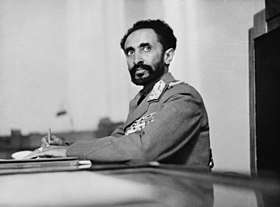

Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini had imperial ambitions in Abyssinia. Italy was already in possession of neighbouring Eritrea and Somalia. In December 1934, there was a clash between Italian and Abyssinian troops at Walwal, near the border between British and Italian Somaliland, in which Italian troops took possession of the disputed territory and in which 150 Abyssinians and 50 Italians were killed. When Italy demanded apologies and compensation from Abyssinia, Abyssinia appealed to the League, Emperor Haile Selassie famously appealing in person to the assembly in Geneva. The League persuaded both sides to seek a settlement under the Italo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1928 but Italy continued troop movements and Abyssinia appealed to the League again. In October 1935 Mussolini launched an attack on Abyssinia. The League declared Italy to be the aggressor and imposed sanctions, but coal and oil were not included; blocking these, it was thought, would provoke war. Albania, Austria, and Hungary refused to apply sanctions; Germany and the United States were not in the League. Nevertheless, the Italian economy suffered. The League considered closing off the Suez Canal also, which would have stopped arms to Abyssinia, but, thinking it would be too harsh a measure, they did not do so.[9]

Earlier, in April 1935, Italy had joined Britain and France in protest against Germany's rearmament. France was anxious to placate Mussolini so as to keep him away from an alliance with Germany. Britain was less hostile to Germany and set the pace in imposing sanctions and moved a naval fleet into the Mediterranean. But in November 1935, the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare and the French Prime Minister, Pierre Laval, had secret discussions in which they agreed to concede two-thirds of Abyssinia to Italy. However, the press leaked the content of the discussions and a public outcry forced Hoare and Laval to resign. In May 1936, undeterred by sanctions, Italy captured Addis Ababa, the Abyssinian capital, and proclaimed Victor Emmanuel III the Emperor of Ethiopia. In July the League abandoned sanctions. This episode, in which sanctions were incomplete and appeared to be easily given up, seriously discredited the League.

Remilitarisation of the Rhineland

Under the Versailles Settlement, the Rhineland was demilitarised. Germany accepted this arrangement under the Locarno Treaties of 1925. Hitler claimed that it threatened Germany and on 7 March 1936, he sent German forces into the Rhineland. He gambled on Britain not getting involved but was unsure how France would react. The action was opposed by many of his advisers. His officers had orders to withdraw if they met French resistance. France consulted Britain and lodged protests with the League, but took no action. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin said that Britain lacked the forces to back its guarantees to France and that in any case, public opinion would not allow it. In Britain, it was thought that the Germans were merely walking into "their own backyard". Hugh Dalton, a Labour Party MP who usually advocated stiff resistance to Germany, said that neither the British people nor Labour would support military or economic sanctions.[9] In the Council of the League, only the Soviet Union proposed sanctions against Germany. Hitler was invited to negotiate. He proposed a non-aggression pact with the Western powers. When asked for details he did not reply. Hitler's occupation of the Rhineland had persuaded him that the international community would not resist him and put Germany in a powerful strategic position.

Spanish Civil War

Many historians argue that the British policy of non-intervention was a product of the Establishment's anti-Communist stance. Scott Ramsay (2019) instead argues that Britain demonstrated of "benevolent neutrality". It was simply hedging its bets, avoiding favouring one side or the other. The goal was that in a European war Britain would enjoy the 'benevolent neutrality' of whichever side won in Spain.[10]

Conduct of appeasement, 1937–39

In 1937 Stanley Baldwin resigned as Prime Minister and Neville Chamberlain took over. Chamberlain pursued a policy of appeasement and rearmament.[11] Chamberlain's reputation for appeasement rests in large measure on his negotiations with Hitler over Czechoslovakia in 1938.

Anschluss

When the German Empire and Austro-Hungarian Empire were broken up in 1918, Austria was left as a rump state with the temporary adopted name Deutschösterreich ("German-Austria"), with the vast majority of the Austrian Germans wanting to join Germany. However, the victors' agreements of World War I (Treaty of Versailles and the Treaty of Saint-Germain) strictly forbade union between Austria and Germany, as well as the name "German-Austria", which reverted to "Austria" after the emergence of the First Republic of Austria in September 1919. The constitutions of both the Weimar Republic and the First Austrian Republic included the aim of unification, which was supported by democratic parties. However, the rise of Hitler dampened the enthusiasm of the Austrian government for such a plan. Hitler, an Austrian by birth, had been a pan-German from a very young age and had promoted a Pan-German vision of a Greater German Reich from the beginning of his career in politics. He said in Mein Kampf (1924) that he would attempt a union of his birth country Austria with Germany, by any means possible and by force if necessary. By early 1938, Hitler had consolidated his power in Germany and was ready to implement this long-held plan.

The Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg wished to pursue ties with Italy, but turned to Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Romania (the Little Entente). To this Hitler took violent exception. In January 1938 the Austrian Nazis attempted a putsch, following which some were imprisoned. Hitler summoned Schuschnigg to Berchtesgaden in February and demanded, with the threat of military action, that he release imprisoned Austrian Nazis and allow them to participate in the government. Schuschnigg complied and appointed Arthur Seyss-Inquart, a pro-Nazi lawyer, as interior minister. To forestall Hitler and to preserve Austria's independence, Schuschnigg scheduled a plebiscite on the issue for 13 March. Hitler demanded that the plebiscite be canceled. The German ministry of propaganda issued press reports that riots had broken out in Austria and that large parts of the Austrian population were calling for German troops to restore order. On 11 March, Hitler sent an ultimatum to Schuschnigg, demanding that he hand over all power to the Austrian Nazis or face an invasion. The British Ambassador in Berlin registered a protest with the German government against the use of coercion against Austria. Schuschnigg, realizing that neither France nor the United Kingdom would actively support him, resigned in favor of Seyss-Inquart, who then appealed to German troops to restore order. On 12 March the 8th German Wehrmacht crossed the Austrian border. They met no resistance and were greeted by cheering Austrians. This invasion was the first major test of the Wehrmacht's machinery. Austria became the German province of Ostmark, with Seyss-Inquart as governor. A plebiscite was held on 10 April and officially recorded a support of 99.73% of the voters.[12]

Although the victorious Allies of World War I had prohibited the union of Austria and Germany, their reaction to the Anschluss was mild.[13] Even the strongest voices against annexation, particularly those of Fascist Italy, France and Britain (the "Stresa Front") were not backed by force. In the House of Commons Chamberlain said that "The hard fact is that nothing could have arrested what has actually happened [in Austria] unless this country and other countries had been prepared to use force."[14] The American reaction was similar. The international reaction to the events of 12 March 1938 led Hitler to conclude that he could use even more aggressive tactics in his plan to expand the Third Reich. The Anschluss paved the way for Munich in September 1938 because it indicated the likely non-response of Britain and France to future German aggression.

Munich Agreement

|

"How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks here because of a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing." Neville Chamberlain, 27 September 1938, 8 p.m. radio broadcast, on Czechoslovak refusal to accept Nazi demands to cede border areas to Germany. |

Under the Versailles Settlement, Czechoslovakia was created with the territory of the Czech part more or less corresponding to the Czech Crown lands as they had existed within the Austria-Hungary and before. It included Bohemia, Moravia, and Slovakia and had border areas with a majority German population known as the Sudetenland and areas with significant numbers of other ethnic minorities (notably Hungarians, Poles, and Ruthenes). In April 1938, Sudeten Nazis, led by Konrad Henlein, agitated for autonomy and then threatened, in Henlein's words, "direct action to bring the Sudeten Germans within the frontiers of the Reich".[15] An international crisis ensued.

France and Britain advised Czech acceptance of Sudeten autonomy. The Czech government refused and ordered a partial mobilization in expectation of German aggression. Lord Runciman was sent by Chamberlain to mediate in Prague and persuaded the Czech government to grant autonomy. Germany escalated the dispute, the German press carrying stories of alleged Czech atrocities against Sudeten Germans and Hitler ordering 750,000 troops to the German-Czech border. In August, Henlein broke off negotiations with the Czech authorities. At a Nazi Party Rally in Nuremberg on 12 September, Hitler made a speech attacking Czechoslovakia[16] and there was an increase of violence by Sudeten Nazis against Czech and Jewish targets.

Chamberlain, faced with the prospect of a German invasion, flew to Berchtesgaden on 15 September to negotiate directly with Hitler. Hitler now demanded that Chamberlain accept not merely Sudeten self-government within Czechoslovakia, but the absorption of the Sudeten lands into Germany. Chamberlain became convinced that refusal would lead to war. The geography of Europe was such that Britain and France could forcibly prevent the German occupation of the Sudetenland only by the invasion of Germany.[17] Chamberlain, therefore, returned to Britain and agreed to Hitler's demands. Britain and France told the Czech president Edvard Beneš that he must hand to Germany all territory with a German majority. Hitler increased his aggression against Czechoslovakia and ordered the establishment of a Sudeten German paramilitary organization, which proceeded to carry out terrorist attacks on Czech targets.

On 22 September, Chamberlain flew to Bad Godesberg for his second meeting with Hitler. He said he was willing to accept the cession of the Sudetenland to Germany. He was startled by Hitler's response: Hitler said that cession of the Sudetenland was not enough and that Czechoslovakia (which he had described as a "fraudulent state") must be broken up completely. Later in the day, Hitler resiled, saying that he was willing to accept the cession of the Sudetenland by 1 October. On 24 September, Germany issued the Godesberg Memorandum, demanding cession by 28 September, or war. The Czechs rejected these demands, France ordered mobilization and Britain mobilized its Navy.

On 26 September Hitler made a speech at the Sportpalast in Berlin in which he claimed that the Sudetenland was "the last territorial demand I have to make in Europe,"[18] and gave Czechoslovakia a deadline of 28 September at 2:00pm to cede the territory to Germany or face war.[19]

In this atmosphere of growing conflict, Mussolini persuaded Hitler to put the dispute to a four-power conference and on 29 September 1938, Hitler, Chamberlain, Édouard Daladier (the French Prime Minister) and Mussolini met in Munich. Czechoslovakia was not to be a party to these talks, nor was the Soviet Union. The four powers agreed that Germany would complete its occupation of the Sudetenland but that an international commission would consider other disputed areas. Czechoslovakia was told that if it did not submit, it would stand alone. At Chamberlain's request, Hitler readily signed a peace treaty between the United Kingdom and Germany. Chamberlain returned to Britain promising "peace for our time". Before Munich, President Roosevelt sent a telegram to Chamberlain saying "Goodman", and afterward told the American ambassador in Rome, "I am not a bit upset over the final result."[20]

As a result of the annexation of the Sudetenland, Czechoslovakia lost 800,000 citizens, much of its industry and its mountain defenses in the west. It left the rest of Czechoslovakia weak and powerless to resist subsequent occupation. In the following months Czechoslovakia was broken up and ceased to exist as Germany annexed the Sudetenland, Hungary part of Slovakia including Carpathian Ruthenia, and Poland Zaolzie. On 15 March 1939, the German Wehrmacht moved into the remainder of Czechoslovakia and, from Prague Castle, Hitler proclaimed Bohemia and Moravia the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, completing the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. An independent Slovakia was created under a pro-Nazi puppet government.

In March 1939, Chamberlain foresaw a possible disarmament conference between himself, Edouard Daladier, Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini and Joseph Stalin; his home secretary, Samuel Hoare, said, "These five men, working together in Europe and blessed in their efforts by the President of the United States of America, might make themselves eternal benefactors of the human race."[21]

In effect, the British and French had, through the Munich negotiations, pressured their ally Czechoslovakia to cede part of its territory to a hostile neighbor in order to preserve peace. Winston Churchill likened the negotiations at Berchtesgarten, Bad Godesberg and Munich to a man demanding £1, then, when it is offered, demanding £2, then when it is refused settling for £1.17s.6d.[22] British leaders committed to the Munich Pact in spite of their awareness of Hitler's vulnerability at the time. In August 1938, General Ludwig Beck relayed a message to Lord Halifax explaining that most of the German General Staff were preparing a coup against the Fuhrer, but would only attack with "proof that England will fight if Czechoslovakia is attacked". When Chamberlain received the news, he dismissed it out of hand. In September, the British received assurance that the General Staff's offer to launch the coup still stood, with key private sector, police and army support, even though Beck had resigned his post.[23] Chamberlain ultimately ceded to all of Hitler's demands at Munich because he believed Britain and Nazi Germany were "the two pillars of European peace and buttresses against communism".[24][25]

Czechoslovakia had a modern, well-prepared military and Hitler, on entering Prague, conceded that a war would have cost Germany much blood.[26][22] But the decision by France and Great Britain not to defend Czechoslovakia in the event of war (and the exclusion from the equation of the Soviet Union, whom Chamberlain distrusted) meant that the outcome would have been uncertain.[22] This event forms the main part of what became known as Munich betrayal (Czech: Mnichovská zrada) in Czechoslovakia and the rest of Eastern Europe,[27] as the Czech view was that Britain and France pressured them to cede territory in order to prevent a major war that would involve the West. The Western view is that they were pressured in order to save Czechoslovakia from total annihilation.

Outbreak of war

By August 1939 Hitler was convinced that the democratic nations would never put up any effective opposition to him. He expressed his contempt for them in a speech he delivered to his Commanders in Chief: "Our enemies have leaders who are below the average. No personalities. No masters, no men of action… Our enemies are small fry. I saw them in Munich."[28]

On 1 September 1939, German forces invaded Poland; Britain and France joined the war against Germany. Following the German invasion of Norway, opinion turned against Chamberlain's conduct of the war; he resigned, and on 10 May 1940 Winston Churchill became Prime Minister. In July, following the Fall of France, when Britain stood almost alone against Germany, Hitler offered peace. Some politicians inside and outside the government were willing to consider the offer but Churchill would not.[29] Chamberlain died on 9 November the same year. Churchill delivered a tribute to him in which he said, "Whatever else history may or may not say about these terrible, tremendous years, we can be sure that Neville Chamberlain acted with perfect sincerity according to his lights and strove to the utmost of his capacity and authority, which were powerful, to save the world from the awful, devastating struggle in which we are now engaged."[30]

Attitudes towards appeasement

As the policy of appeasement failed to prevent war, those who advocated it were quickly criticized. Appeasement came to be seen as something to be avoided by those with responsibility for the diplomacy of Britain or any other democratic country. By contrast, the few who stood out against appeasement were seen as "voices in the wilderness whose wise counsels were largely ignored, with almost catastrophic consequences for the nation in 1939–40".[31] More recently, however, historians have questioned the accuracy of this simple distinction between appeasers and anti-appeasers. "Few appeasers were really prepared to seek peace at any price; few, if any, anti-appeasers were prepared for Britain to make a stand against aggression whatever the circumstances and wherever the location in which it occurred."[31]

Remembering the horrors and mistakes of the First World War

Chamberlain's policy in many respects continued the policies of MacDonald and Baldwin, and was popular until the failure of the Munich Agreement to stop Hitler in Czechoslovakia. "Appeasement" had been a respectable term between 1919 and 1937 to signify the pursuit of peace.[32] Many believed after the First World War that wars were started by mistake, in which case the League of Nations could prevent them, or that they were caused by large-scale armaments, in which case disarmament was the remedy, or that they were caused by national grievances, in which case the grievances should be redressed peacefully.[9] Many thought that the Versailles Settlement had been unjust, that the German minorities were entitled to self-determination and that Germany was entitled to equality in armaments.

Government views

Appeasement was accepted by most of those responsible for British foreign policy in the 1930s, by leading journalists and academics and by members of the royal family, such as King Edward VIII and his successor, George VI.[31] Anti-communism was sometimes acknowledged as a deciding factor, as mass labour unrest resurfaced in Britain, and news of Stalin's bloody purges disturbed the West. A common upper-class slogan was "better Hitlerism than Communism".[33] (In France, right-wingers were sometimes heard to chant "Better Hitler than Blum," referring to their socialist Prime Minister at the time.)[34]

Most Conservative MPs were also in favour, though Churchill said their supporters were divided and in 1936 he led a delegation of leading Conservative politicians to express to Baldwin their alarm about the speed of German rearmament and the fact that Britain was falling behind.[22] Amongst Conservatives, Churchill was unusual in believing that Germany menaced freedom and democracy, that British rearmament should proceed more rapidly and that Germany should be resisted over Czechoslovakia. His criticism of Hitler began from the start of the decade, yet Churchill was slow to attack fascism overall due to his own vitriolic opposition to Communists, "international Jews", and socialism generally.[35] Churchill's sustained warnings about fascism only commenced in 1938 after Hitler's ally, Francisco Franco, decimated the left in Spain.[36]

The week before Munich, Churchill warned "The partition of Czechoslovakia under pressure from England and France amounts to the complete surrender of the Western Democracies to the Nazi threat of force. Such a collapse will bring peace or security neither to England nor to France."[22] He and a few other Conservatives who refused to vote for the Munich settlement were attacked by their local constituency parties.[22] But Churchill's leadership of Britain during the war and his role in creating the post-war consensus against appeasement has tended to obscure the fact that "his contemporary criticism of totalitarian regimes other than Hitler's Germany was at best muted".[31] Not until May 1938 did he begin "consistently to withhold his support from the National Government's conduct of foreign policy in the division lobbies of the House of Commons", and he seems "to have been convinced by the Sudeten German leader, Henlein, in the spring of 1938, that a satisfactory settlement could be reached if Britain managed to persuade the Czech government to make concessions to the German minority".[31]

Military views

In Britain the Royal Navy generally favored appeasement. In the Italian Abyssinia Crisis of 1937 it was confident it could easily defeat the Italian Navy in open warfare. However, it favored appeasement because it did not want to commit a large fraction of its naval power to the Mediterranean, thereby weakening its positions against Germany and Japan.[37] In 1938, the Royal Navy approved appeasement regarding Munich because it calculated that at that moment, Britain lacked the political and military resources to intervene and still maintain an imperial defence capability.[38][39]

Public opinion in Britain throughout the 1930s was frightened by the prospect of German terror bombing of British cities, as they had started to do in the First World War. The media emphasized the dangers, and the general consensus was that defense was impossible and, as Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin had said in 1932" the "bombers will always get through".[40] However, the Royal Air Force had two major weapons systems in the works—better interceptors (Hurricanes and Spitfires) and especially radar. These promised to counter the German bombing offensive. However they were not yet ready, so that appeasement was necessary to cause a delay.[41][42] Specifically regarding the fighters, the RAF warned the government in October 1938 that the German bombers would probably get through: "the situation... will be definitely unsatisfactory throughout the next twelve months."[43]

In France, the Air Force intelligence section closely examined the strength of the Luftwaffe. It decided the German pursuit planes and bombers were the best in the world, and that the Nazis were producing 1000 warplanes a month. They perceived decisive German air superiority, so the Air Force was pessimistic about its ability to defend Czechoslovakia in 1938. Guy La Chambre, the civilian air minister, optimistically informed the government that the air force was capable of stopping the Luftwaffe. However, General Joseph Vuillemin, air force chief of staff, warned that his arm was far inferior. He consistently opposed war with Germany.[44]

Opposition parties

The Labour Party opposed the Fascist dictators on principle, but until the late 1930s it also opposed rearmament and it had a significant pacifist wing.[45][46] In 1935 its pacifist leader George Lansbury resigned following a party resolution in favour of sanctions against Italy, which he opposed. He was replaced by Clement Attlee, who at first opposed rearmament, advocating the abolition of national armaments and a world peace-keeping force under the direction of the League of Nations.[47] However, with the rising threat from Nazi Germany, and the ineffectiveness of the League of Nations, this policy eventually lost credibility, and in 1937 Ernest Bevin and Hugh Dalton persuaded the party to support rearmament[48] and oppose appeasement.[49]

A few on the left said that Chamberlain looked forward to a war between Germany and Russia.[9] The Labour Party leader Clement Attlee claimed in one political speech in 1937 that the National Government had connived at German rearmament "because of its hatred of Russia".[45] British Communists, following the party line defined by Joseph Stalin,[50] argued that appeasement had been a pro-Fascist policy and that the British ruling class would have preferred fascism to socialism. The Communist MP Willie Gallacher said that "many prominent representatives of the Conservative Party, speaking for powerful landed and financial interests in the country, would welcome Hitler and the German Army if they believed that such was the only alternative to the establishment of Socialism in this country."[51]

Public opinion

British public opinion had been strongly opposed to war and rearmament at the beginning of the 1930s, although this began to shift by mid-decade. At a debate at Oxford University in 1933, a group of undergraduates passed a motion saying that they would not fight for King and country, which persuaded some in Germany that Britain would never go to war.[22] Baldwin told the House of Commons that in 1933 he had been unable to pursue a policy of rearmament because of the strong pacifist sentiment in the country.[22] In 1935, eleven million responded to the League of Nations "Peace Ballot" by pledging support for the reduction of armaments by international agreement.[22] On the other hand, the same survey also found that 58.7% of British voters favored "collective military sanctions" against aggressors, and public reaction to the Hoare-Laval Pact with Mussolini was extremely unfavorable.[52] Even the left-wing of the pacifist movement quickly began to turn with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 and many peace-balloters began signing up for the international brigades to fight Hitler's ally Francisco Franco. By the height of the Spanish conflict in 1937, the majority of young pacifists had modified their views to accept that war could be a legitimate response to aggression and fascism.[53][54]

Czechoslovakia did not concern most people until the middle of September 1938, when they began to object to a small democratic state being bullied.[9][15] Nevertheless, the initial response of the British public to the Munich agreement was generally favorable.[9] As Chamberlain left for Munich in 1938, the whole House of Commons cheered him noisily. On 30 September, on his return to Britain, Chamberlain delivered his famous "peace for our time" speech to delighted crowds. He was invited by the Royal family onto the balcony at Buckingham Palace before he had reported to Parliament. The agreement was supported by most of the press, only Reynold's News and the Daily Worker dissenting.[9] In parliament the Labour Party opposed the agreement. Some Conservatives abstained in the vote. However, the only MP to advocate war was the Conservative Duff Cooper, who had resigned from the government in protest against the agreement.[9]

Role of the media

Positive opinion of appeasement was shaped partly by media manipulation. The German correspondent for the Times of London, Norman Ebbutt, charged that his persistent reports about Nazi militarism were suppressed by his editor Geoffrey Dawson. Historians such as Richard Cockett, William Shirer, and Frank McDonough have confirmed the claim,[55][56] and also noted the links between The Observer and the pro-appeasement Cliveden Set.[57] The results of an October 1938 Gallup poll which showed 86% of the public believed Hitler was lying about his future territorial ambitions was censored from the News Chronicle at the last minute by the publisher, who was loyal to Chamberlain.[58] For the few journalists who were asking challenging questions about appeasement – primarily members of the foreign press – Chamberlain often froze them out or intimidated them. When asked at press conferences about Hitler's abuse of Jews and other minority groups, he went so far as to denounce these reports as "Jewish-Communist propaganda".[59]

Chamberlain's direct manipulation of the BBC was sustained and egregious.[60] For example, Lord Halifax told radio producers not to offend Hitler and Mussolini, and they complied by censoring anti-fascist commentary made by Labour and Popular Front MPs. The BBC also suppressed the fact that 15,000 people protested the prime minister in Trafalgar Square as he returned from Munich in 1938 (10,000 more than welcomed him at 10 Downing St.).[61] The BBC radio producers continued to censor news of Jewish persecution even after the war broke out, as Chamberlain still held out hopes of a quick armistice and didn't want to inflame the atmosphere.[62] As Richard Cockett noted:

[Chamberlain] had successfully demonstrated how a government in a democracy could influence and control the press to a remarkable degree. The danger in this for Chamberlain was that he preferred to forget that he exercised such influence, and so increasingly mistook his pliant press for real public opinion...the truth of the matter was that by controlling the press he was merely ensuring that the press was unable to reflect public opinion.[63]

The journalist Shiela Grant Duff's Penguin Special, Europe and the Czechs was published and distributed to every MP on the day that Chamberlain returned from Munich. Her book was a spirited defence of the Czech nation and a detailed criticism of British policy, confronting the need for war if necessary. It was influential and widely read. Although she argued against the policy of "peace at almost any price"[64] she did not take the personal tone that Guilty Men was to take two years later.

At the start of World War II

Once Germany invaded Poland, igniting World War II, consensus was that appeasement was responsible. The Labour MP Hugh Dalton identified the policy with wealthy people in the City of London, Conservatives and members of the peerage who were soft on Hitler.[65] The appointment of Churchill as Prime Minister hardened opinion against appeasement and encouraged the search for those responsible. Three British journalists, Michael Foot, Frank Owen and Peter Howard, writing under the name of "Cato" in their book Guilty Men, called for the removal from office of 15 public figures they held accountable, including Chamberlain and Baldwin. The book defined appeasement as the "deliberate surrender of small nations in the face of Hitler's blatant bullying". It was hastily written and has few claims to historical scholarship,[66] but Guilty Men shaped subsequent thinking about appeasement and it is said[67][68] that it contributed to the defeat of the Conservatives in the 1945 general election.

The change in the meaning of "appeasement" after Munich was summarized later by the historian David Dilks: "The word in its normal meaning connotes the pacific settlement of disputes; in the meaning usually applied to the period of Neville Chamberlain['s] premiership, it has come to indicate something sinister, the granting from fear or cowardice of unwarranted concessions in order to buy temporary peace at someone else's expense."[69]

After the Second World War: historians

Churchill's book The Gathering Storm, published in 1948, made a similar judgment to Guilty Men, though in moderate tones. This book and Churchill's authority confirmed the orthodox view.

Historians have subsequently explained Chamberlain's policies in various ways. It could be said that he believed sincerely that the objectives of Hitler and Mussolini were limited and that the settlement of their grievances would protect the world from war; for safety, military and air power should be strengthened. Many have judged this belief to be fallacious, since the dictators' demands were not limited and appeasement gave them time to gain greater strength.

In 1961 this view of appeasement as avoidable error and cowardice was set on its head by A.J.P. Taylor in his book The Origins of the Second World War. Taylor argued that Hitler did not have a blueprint for war and was behaving much as any other German leader might have done. Appeasement was an active policy, and not a passive one; allowing Hitler to consolidate was a policy implemented by "men confronted with real problems, doing their best in the circumstances of their time". Taylor said that appeasement ought to be seen as a rational response to an unpredictable leader, appropriate to the time both diplomatically and politically.

His view has been shared by other historians, for example Paul Kennedy, who says of the choices facing politicians at the time, "Each course brought its share of disadvantages: there was only a choice of evils. The crisis in the British global position by this time was such that it was, in the last resort, insoluble, in the sense that there was no good or proper solution."[70] Martin Gilbert has expressed a similar view: "At bottom, the old appeasement was a mood of hope, Victorian in its optimism, Burkean in its belief that societies evolved from bad to good and that progress could only be for the better. The new appeasement was a mood of fear, Hobbesian in its insistence upon swallowing the bad in order to preserve some remnant of the good, pessimistic in its belief that Nazism was there to stay and, however horrible it might be, should be accepted as a way of life with which Britain ought to deal."[71]

The arguments in Taylor's Origins of the Second World War (sometimes described as "revisionist"[9][72]) were rejected by many historians at the time, and reviews of his book in Britain and the United States were generally critical. Nevertheless, he was praised for some of his insights. By showing that appeasement was a popular policy and that there was continuity in British foreign policy after 1933, he shattered the common view of the appeasers as a small, degenerate clique that had mysteriously hijacked the British government sometime in the 1930s and who had carried out their policies in the face of massive public resistance; and by portraying the leaders of the 1930s as real people attempting to deal with real problems, he made the first strides towards explaining the actions of the appeasers rather than merely condemning them.

In the early 1990s a new theory of appeasement, sometimes called "counter-revisionist",[72] emerged as historians argued that appeasement was probably the only choice for the British government in the 1930s, but that it was poorly implemented, carried out too late and not enforced strongly enough to constrain Hitler. Appeasement was considered a viable policy, considering the strains that the British Empire faced in recuperating from World War I, and Chamberlain was said to have adopted a policy suitable to Britain's cultural and political needs. Frank McDonough is a leading proponent of this view of appeasement and describes his book Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War[73] as a "post revisionist" study.[74] Appeasement was a crisis management strategy seeking a peaceful settlement of Hitler's grievances. "Chamberlain's worst error", says McDonough, "was to believe that he could march Hitler on the yellow brick road to peace when in reality Hitler was marching very firmly on the road to war." He has criticized revisionist historians for concentrating on Chamberlain's motivations rather than how appeasement worked in practice – as a "usable policy" to deal with Hitler. James P. Levy argues against the outright condemnation of appeasement. "Knowing what Hitler did later," he writes, "the critics of Appeasement condemn the men who tried to keep the peace in the 1930s, men who could not know what would come later. ... The political leaders responsible for Appeasement made many errors. They were not blameless. But what they attempted was logical, rational, and humane."[75]

The view of Chamberlain colluding with Hitler to attack Russia has persisted, however, particularly on the far-left.[76] In 1999, Christopher Hitchens wrote that Chamberlain "had made a cold calculation that Hitler should be re-armed...partly to encourage his 'tough-minded' solution to the Bolshevik problem in the East".[34] While consciously encouraging war with Stalin is not widely accepted to be a motive of the Downing Street appeasers, there is historical consensus that anti-communism was central to appeasement's appeal for the conservative elite.[33] As Antony Beevor writes, "The policy of appeasement was not Neville Chamberlin's invention. Its roots lay in a fear of bolshevism. The general strike of 1926 and the depression made the possibility of revolution a very real concern to conservative politicians. As a result, they had mixed feelings towards the German and Italian regimes which had crushed the communists and socialists in their own countries."[77]

After the Second World War: politicians

Statesmen in the post-war years have often referred to their opposition to appeasement as a justification for firm, sometimes armed, action in international relations.

U.S. President Harry S. Truman thus explained his decision to enter the Korean War in 1950, British Prime Minister Anthony Eden his confrontation of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the Suez Crisis of 1956, U.S. President John F. Kennedy his "quarantine" of Cuba in 1962, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson his resistance to communism in Indochina in the 1960s, and U.S. President Ronald Reagan his air strike on Libya in 1986.[78]

During the Cold War, the "lessons" of appeasement were cited by prominent conservative allies of Reagan, who urged Reagan to be assertive in "rolling back" Soviet-backed regimes throughout the world. The Heritage Foundation's Michael Johns, for instance, wrote in 1987 that "seven years after Ronald Reagan's arrival in Washington, the United States government and its allies are still dominated by the culture of appeasement that drove Neville Chamberlain to Munich in 1938."[79]

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher invoked the example of Churchill during the Falklands War of 1982: "When the American Secretary of State, Alexander Haig, urged her to reach a compromise with the Argentines she rapped sharply on the table and told him, pointedly, 'that this was the table at which Neville Chamberlain sat in 1938 and spoke of the Czechs as a faraway people about whom we know so little'."[80] The spectre of appeasement was raised in discussions of the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.[81]

U.S. President George W. Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair also cited Churchill's warnings about German rearmament to justify their action in the run-up to the 2003 Iraq War.[82]

In May 2008, President Bush cautioned against "the false comfort of appeasement" when dealing with Iran and its President, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[83]

Dutch politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali demands a confrontational policy at the European level to meet the threat of radical Islam, and compares policies of non-confrontation to Neville Chamberlain's appeasement of Hitler.[84]

Tibetan separatists consider the policy of the West towards China with regard to Tibet as appeasement.[85]

See also

|

|

|

References

- Appeasement – World War 2 on History Archived 4 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Robert Mallett, "The Anglo‐Italian war trade negotiations, contraband control and the failure to appease Mussolini, 1939–40." Diplomacy and Statecraft 8.1 (1997): 137–67.

- Andrew Roberts, "'Appeasement' Review: What Were They Thinking? Britain’s establishment coalesced around appeasement and bared its teeth at those who dared to oppose it," [https://www.wsj.com/articles/appeasement-review-what-were-they-thinking-11572619353 Wall Street Journal 1 Nov. 2019).

- Frank McDonough (1998). Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement, and the British Road to War. Manchester UP. p. 114.

- Hunt, The Makings of the West p. 861

- Andrew Roberts, "'Appeasement' Review" Wall Street Journal Nov. 1, 2019

- Clauss, E. M. (1970). "The Roosevelt Administration and Manchukuo, 1933?1941". The Historian. 32 (4): 595–611. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1970.tb00380.x.

- Thomson, David (1957) Europe Since Napoleon, London: Longans Green & Co. p. 691

- Taylor, A.J.P., English History, 1914–1945, 1965

- Scott Ramsay. "Ensuring Benevolent Neutrality: The British Government’s Appeasement of General Franco during the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939". International History Review 41:3 (2019): 604–623. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2018.1428211.

- Mujtaba Haider Zaidi "Chamberlain and Hitler vs. Pakistan and Taliban" The Frontier Post Newspaper, 3 July 2013 URL:

- Richard J. Evans, The Third Reich in Power (2006) pp. 646–58

- Alfred D. Low, The Anschluss Movement 1931–1938 and the Great Powers (1985)

- Shirer, William L. (1984). Twentieth Century Journey, Volume 2, The Nightmare Years: 1930–1940. Boston: Little Brown and Company. pp. 308. ISBN 0-316-78703-5.

- Grant Duff 1938.

- Donald Cameron Watt, How War Came: The Immediate Origins of the Second World War (1989) ch. 2

- A. J. P. Taylor, English History, 1914–1945, p. 415

- Domarus, Max; Hitler, Adolf (1990). Hitler: Speeches and Proclamations, 1932–1945 : The Chronicle of a Dictatorship. p. 1393.

- Corvaja, Santi and Miller, Robert L. (2008) Hitler & Mussolini: The Secret Meetings. New York: Enigma Books. ISBN 9781929631421. p.73

- The Versailles Treaty and its Legacy: The Failure of the Wilsonian Vision, by Norman A. Graebner, Edward M. Bennett

- International: Peace Week, Time magazine, 20 March 1939

- Winston Churchill, The Gathering Storm, 1948

- Nigel Jones. Countdown to Valkyrie: The July Plot to Assassinate Hitler. pp. 60–65.

- Michael McMenamin, "Munich Timeline" Finest Hour 162, Spring 2014, International Winston Churchill Society

- Louise Grace Shaw, The British Political Elite and the Soviet Union (Routledge, 2013), pp. 16–24

- Grant Duff 1938, p. 137.

- František Halas, Torzo naděje (1938), poem Zpěv úzkosti, "Zvoní zvoní zrady zvon zrady zvon, Čí ruce ho rozhoupaly, Francie sladká hrdý Albion, a my jsme je milovali"

- Hitler’s Speech to the Commanders in Chief (22 August 1939), German History in Documents and Images (GHDI), http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/docpage.cfm?docpage_id=2287&language=english

- Richard Overy, "Civilians on the front-line", The Second World War – Day 2: The Blitz, The Guardian/The Observer, September 2009

- Churchill's tribute to Chamberlain, 12 November 1940 Archived 2 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Medlicott, W.N., Review of "The Roots of Appeasement" by M.Gilbert (1966), in The English Historical Review, Vol. 83, No. 327 (Apr. 1968), p. 430

- "An evaluation of the reasons for the British policy of appeasement, 1936–1938" BBC History

- Christopher Hitchens, "Imagining Hitler" Vanity Fair, February 15, 1999

- Antoine Capet “The Creeds of the Devil: Churchill between the Two Totalitarianisms, 1917–1945 (Part 1)" International Churchill Society

- Antoine Capet “The Creeds of the Devil: Churchill between the Two Totalitarianisms, 1917–1945 (Part 2)" International Churchill Society

- Arthur Marder, "The Royal Navy and the Ethiopian Crisis of 1935–36." American Historical Review 75.5 (1970): 1327–1356. online

- G. A. H. Gordon, "The admiralty and appeasement." Naval History 5.2 (1991): 44+.

- Joseph Maiolo , The Royal Navy and Nazi Germany, 1933–39: A Study in Appeasement and the Origins of the Second World War (1998).

- John Terraine, "The Spectre of the Bomber," History Today (1982) 32#4 pp. 6–9.

- Zara Steiner, The triumph of the dark: European international history 1933–1939 (2011) pp 606–9, 772.

- Walter Kaiser, "A case study in the relationship of history of technology and of general history: British radar technology and Neville Chamberlain's appeasement policy." Icon (1996) 2: 29–52. online

- N. H. Gibbs, Grand Strategy. Vol. 1 1976) p 598.

- Peter Jackson, 'La perception de la puissance aérienne allemande et son influence sur la politique extérieure française pendant les crises internationales de 1938 à 1939', Revue Historique des Armées, 4 (1994), pp. 76–87

- Toye, Richard (2001), "The Labour Party and the Economics of Rearmament, 1935–1939" (PDF), Twentieth Century British History, 12: 303–326

- Rhiannon Vickers, The Labour Party and the World: The evolution of Labour's foreign policy, Manchester University Press, 2003, Chapter 5

- "Defence". 299 cc35-174. Commons and Lords Hansard. 11 March 1935. Retrieved 20 March 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - A.J.Davies, To Build A New Jerusalem: The British Labour Party from Keir Hardie to Tony Blair, Abacus, 1996

- Clem Attlee: A Biography By Francis Beckett, Richard Cohen Books, ISBN 1-86066-101-7

- Teddy J. Uldricks, "Russian Historians Reevaluate the Origins of World War II," History & Memory Volume 21, Number 2, Fall/Winter 2009, pp. 60–82 (in Project Muse)

- Willie Gallacher, The Chosen Few, Lawrence and Wishart, 1940

- Eric Dorn Brose, A history of Europe in the twentieth century (Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 208

- Rosenstone, Robert A., Crusade of the Left (Transaction Publishers), p. 215

- Richard Overy, "Parting with Pacifism: In the Mid-1930s Many Millions of British People Voted Overwhelmingly against Any Return to Conflict. but Events in Spain Changed Public Opinion" History Today, Vol. 59, No. 8, August 2009

- Gossen, David J. "Public opinion, Appeasement, and The Times : Manipulating Consent in the 1930s" M.A. Thesis, History Department, University of British Columbia

- "Twilight of Truth: Chamberlain, Appeasement and The Manipulation of the Press | Richard Cockett". Richard Cockett. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement, and the British Road to War (Manchester University Press,1998), pp. 114–19

- Lynne Olson, Troublesome Young Men: The Rebels Who Brought Churchill to Power and Helped Save England (Farrar, Straus and Giroux;, 2008), pp. 178–79

- Olson, Lynne (2008) Troublesome Young Men: The Rebels Who Brought Churchill to Power and Helped Save England New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 120–22]

- David Deacon, "A Quieting Effect? The BBC and the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939)." Media History, 18 (2), pp. 143–58

- McDonough, Frank (1998) Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement, and the British Road to War Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 124–33]

- Olson, Lynne (2008)Troublesome Young Men: The Rebels Who Brought Churchill to Power and Helped Save England New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 258

- Cited in Caputi, Robert J. (2000) Neville Chamberlain and Appeasement Susquehanna University Press, pp. 168–69

- Grant Duff 1938, p. 201.

- Dalton, H. Hitler's War, London, Penguin Books, 1940

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- David Willets and Richard Forsdyke, After the Landslide, London: Centre For Policy Studies, 1999

- Hal G.P. Colebatch, "Epitaph for a Liar", American Spectator, 3.8.10 Archived 17 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Dilks, D. N., "Appeasement Revisited", Journal of Contemporary History, 1972

- Kennedy, Paul M. (1983). Strategy and Diplomacy, 1870–1945: Eight Studies. London: George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-00-686165-2.

- Gilbert, M., The Roots of Appeasement, 1968

- Dimuccio, R.A.B., "The Study of Appeasement in International Relations: Polemics, Paradigms, and Problems", Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 35, No. 2, March 1998

- Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War, Manchester University Press, 1998

- See, for example, McDonough, F., Brown, R., and Smith, D., Hitler, Chamberlain and Appeasement, 2002

- James P. Levy, Appeasement and rearmament: Britain, 1936–1939, Rowman and Littlefield, 2006

- See, for example, Clement Leibovitz and Alvin Finkel, In Our Time: The Chamberlain–Hitler Collusion, Monthly Review Press, 1997 ISBN 0-85345-999-1

- Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939 (Penguin, 2006), p. 133

- Beck, R.J., "Munich's Lessons Reconsidered", International Security, Vol. 14, No. 2, (Autumn, 1989), pp. 161–91

- "Peace in Our Time: The Spirit of Munich Lives On", by Michael Johns, Policy Review, Summer 1987.

- Harris, Kenneth (1988). Thatcher. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 135. ISBN 0-00-637457-3.

- Vuilliamy, E., "Bosnia: The Crime of Appeasement", International Affairs , 1998, pp. 73–91 Year: 1998

- "Appeasement: The Gathering Storm (Teachers Exercises)". Churchill College Cambridge.

- Thomas, E., "The Mythology of Munich", Newsweek, 23 June 2008, Vol. 151, Issue 25, pp. 22–26

- (in Dutch) Confrontatie, geen verzoening, de Volkskrant, 8 April 2006, copy here

- Penny McRae, "West appeasing China on Tibet, says PM-in-exile", AFP, 15 September 2009

Further reading

- Adams, R.J.Q., British Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of Appeasement, 1935–1939 (1993)

- Alexandroff A. and Rosecrance R., "Deterrence in 1939," World Politics 29#3 (1977), pp. 404–24.

- Beck R.J., "Munich's Lessons Reconsidered" in International Security, 14, 1989

- Bouverie, Tim. Appeasement: Chamberlain, Hitler, Churchill, and the Road to War (2019) online review

- Cameron Watt, Donald. How War Came: Immediate Origins of the Second World War, 1938–39 (1990)

- Doer P.W., British Foreign Policy 1919–39 (1988)

- Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste. France and the Nazi Threat: The Collapse of French Diplomacy 1932–1939 (2004); translation of his highly influential La décadence, 1932–1939 (1979)

- Dutton D., Neville Chamberlain

- Faber, David. Munich, 1938: Appeasement and World War II (2009) excerpt and text search

- Farmer Alan. British Foreign and Imperial Affairs 1919–39 (2000), textbook

- Feiling, Keith. The Life of Neville Chamberlain (1947) online

- Goddard, Stacie E. "The rhetoric of appeasement: Hitler's legitimation and British foreign policy, 1938–39." Security Studies 24.1 (2015): 95–130.

- Grant Duff, Sheila (1938). Europe and the Czechs. London: Penguin.

- Hill C., Cabinet Decisions on Foreign Policy: The British Experience, October 1938 – June 1941, (1991).

- Hucker, Daniel. Public Opinion and the End of Appeasement in Britain and France. (Routledge, 2016).

- Jenkins Roy, Baldwin New York: HarperCollins (1987)

- Johns, Michael, "Peace in Our Time: The Spirit of Munich Lives On", Policy Review magazine, Summer 1987

- Levy J., Appeasement and Rearmament: Britain, 1936–1939, 2006

- McDonough, F., Neville Chamberlain, appeasement, and the British road to war (Manchester UP, 1998)

- Mommsen W.J. and Kettenacker L. (eds), The Fascist Challenge and the Policy of Appeasement, London, George Allen & Unwin, 1983 ISBN 0-04-940068-1.

- Murray, Williamson. "Munich, 1938: The military confrontation." Journal of Strategic Studies (1979) 2#3 pp. 282–302.

- Neville P., Hitler and Appeasement: The British Attempt to Prevent the Second World War, 2005

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Proponents and Critics of Appeasement

- Parker, R.A.C. Chamberlain and appeasement: British policy and the coming of the Second World War (Macmillan, 1993)

- Peden G. C., "A Matter of Timing: The Economic Background to British Foreign Policy, 1937–1939," History, 69, 1984

- Post G., Dilemmas of Appeasement: British Deterrence and Defense, 1934–1937, Cornell UP, 1993.

- Ramsay, Scott. "Ensuring Benevolent Neutrality: The British Government’s Appeasement of General Franco during the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939". International History Review 41:3 (2019): 604–623. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2018.1428211. online review in H-DIPLO

- Record, Jeffrey. Making War, Thinking History: Munich, Vietnam, and Presidential Uses of Force from Korea to Kosovo (Naval Institute Press, 2002).

- Riggs, Bruce Timothy. "Geoffrey Dawson, editor of "The Times" (London), and his contribution to the appeasement movement" (PhD dissertation, U of North Texas, 1993) online, bibliography pp. 229–33.

- Rock S.R., Appeasement in International Politics, 2000

- Rock W.R., British Appeasement in the 1930s

- Shay R.P., British Rearmament in the Thirties: Politics and Profits, Princeton University Press, 1977.

- Sontag, Raymond J. "Appeasement, 1937" Catholic Historical Review 38#4 (1953), pp. 385–396 online

- Stedman, A. D. (2007). 'Then what could Chamberlain do, other than what Chamberlain did'? A Synthesis and Analysis of the Alternatives to Chamberlain's Policy of Appeasing Germany, 1936–1939 (PhD). Kingston University. OCLC 500402799. Docket uk.bl.ethos.440347. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- Valladares, David Miguel. "Imperial Glory or Appeasement? the Cliveden Set’s Influence on British Foreign Policy during the Inter-War Period." (MA thesis, Florida State U. 2014); with detailed bibliography pp. 72–80 online

- Wheeler-Bennett J., Munich: Prologue to Tragedy, New York, Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1948

Historiography

- Barros, Andrew, Talbot C. Imlay, Evan Resnick, Norrin M. Ripsman, and Jack S. Levy. "Debating British Decision-making toward Nazi Germany in the 1930s." International Security 34#1 (2009): 173–98. online.

- Cole, Robert A. "Appeasing Hitler: The Munich Crisis of 1938: A Teaching and Learning Resource," New England Journal of History (2010) 66#2 pp. 1–30.

- Dimuccio, Ralph BA. "The study of appeasement in international relations: Polemics, paradigms, and problems." Journal of peace research 35.2 (1998): 245–259.

- Finney, Patrick. "The romance of decline: The historiography of appeasement and British national identity." Electronic Journal of International History 1 (2000). online; comprehensive evaluation of the scholarship

- Hughes, R. Gerald. "The Ghosts of Appeasement: Britain and the Legacy of the Munich Agreement." Journal of Contemporary History (2013) 48#4 pp. 688–716.

- Record, Jeffrey. "Appeasement Reconsidered – Investigating the Mythology of the 1930s" (Strategic Studies Institute, 2005) online

- Roi, Michael. "Introduction: Appeasement: Rethinking the Policy and the Policy-Makers." Diplomacy and Statecraft 19.3 (2008): 383–390.

- Strang, G. Bruce. "The spirit of Ulysses? Ideology and british appeasement in the 1930s." Diplomacy and Statecraft 19.3 (2008): 481–526.

- Van Tol, David. "History extension 2019: Constructing history case study: Appeasement." Teaching History 51.3 (2017): 35+.

- Walker, Stephen G. "Solving the Appeasement Puzzle: Contending Historical Interpretations of British Diplomacy during the 1930s." British Journal of International Studies 6#3 (1980): 219–46. online.

- Watt, D. C. "The Historiography of Appeasement", in Crisis and Controversy: Essays in Honour of A. J. P. Taylor, ed. A. Sked and C. Cook (London, 1976)