Action of 22 September 1914

The Action of 22 September 1914 was an attack by the German U-boat U-9 that took place during the First World War. Three obsolete Royal Navy cruisers of the 7th Cruiser Squadron, manned mainly by reservists and sometimes referred to as the Live Bait Squadron, were sunk by U-9 while patrolling the southern North Sea.

Neutral ships and trawlers nearby began to rescue survivors but about 1,450 British sailors were killed, many being reservists with families; there was a public outcry in Britain at the losses. The sinkings eroded confidence in the British government and damaged the reputation of the Royal Navy, when many countries were still unsure about taking sides in the war.

Background

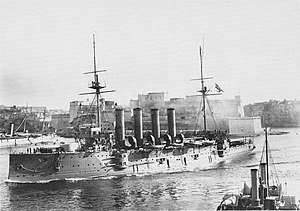

The cruisers were part of the Southern Force (Rear-Admiral Arthur Christian) composed of the flagship Euryalus, the light cruiser Amethyst and the 7th Cruiser Squadron (7th CS, also known as Cruiser Squadron C, Rear-Admiral H. H. Campbell, nicknamed the live-bait squadron), comprising the Cressy-class armoured cruisers HMS Bacchante, Aboukir, Hogue, Cressy and Euryalus, the 1st and 3rd Destroyer flotillas, ten submarines of the 8th Oversea Flotilla and the attached Active-class scout cruiser, Fearless.[1] The force patrolled the North Sea, supporting destroyers and submarines of the Harwich Force to guard against incursions by the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial German Navy) into the English Channel.[2]

Concerns had been expressed about the vulnerability of the ships against modern German cruisers but the War Orders of 28 July 1914, reflecting pre-war assumptions about attacks by destroyers rather than submarines, remained in force. The ships were to patrol the area "south of the 54th parallel clear of enemy torpedo craft and destroyers" supported by Cruiser Force C during the day. The Harwich Patrol guarded the Dogger Bank and the Broad Fourteens further south; usually cruisers were to the north closer to the Dogger Bank and sailed south at night. The cruisers moved to the Broad Fourteens to reinforce the fourth cruiser during troop movements from Britain to France. Heading south put the ships closer to German bases, more vulnerable to submarine attack.[3]

Prelude

On 16 September, Christian had been allowed to keep two cruisers to the north and one at the Broad Fourteens but had kept them together in a central position, able to support operations in both areas. The next day, the destroyer escorts had been forced to depart by heavy weather, which remained so bad that neither patrol could be reformed. The Admiralty ordered that the ships were to cancel the Dogger Patrol and cover the Broad Fourteens until the weather abated. On 20 September, Euryalus returned to port to re-coal and by 22 September, Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy were on patrol under the command of Captain J. E. Drummond of Aboukir.[4] The U-boat was treated lightly by the Imperial German Navy; in the first six weeks of the war, the U-boat arm had sent out ten boats, sunk no ships and lost two boats for their efforts. On the morning of 22 September, U-9 (Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen) passed through the Broad Fourteens on her way back to base and spotted Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy.

Action

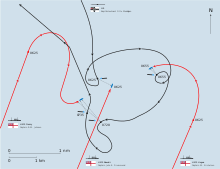

At 06:00 on 22 September, the weather had calmed and the ships were patrolling at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), line abreast, 2 nmi (2.3 mi; 3.7 km) apart. Lookouts were posted for submarine periscopes or ships and one gun on each side of each ship was manned. U-9 had been ordered to attack British transports at Ostend but had been forced to dive and shelter from the storm. On surfacing, she spotted the British ships and moved to attack.[5] At 06:20, U-9 fired a torpedo at the middle ship from a range of 550 yd (500 m) and struck Aboukir on the starboard side, flooding the engine room and causing the ship to stop immediately.[6] No submarines had been sighted, so Drummond assumed that the ship had hit a mine and ordered the other two cruisers to close in to help. After 25 minutes, Aboukir capsized and then sank five minutes later. Only one lifeboat could be launched, because of damage from the explosion and the failure of steam-powered winches needed to launch them.[7]

U-9 rose to periscope depth from her dive after firing the torpedo, to observe two British cruisers engaged in the rescue of men from the sinking ship. Weddigen fired two more torpedoes at Hogue, from 300 yd (270 m). As the torpedoes left the submarine, her bows rose out of the water and she was spotted by Hogue, whose gunners opened fire before the submarine dived. The two torpedoes struck Hogue and within five minutes Captain Wilmot Nicholson gave the order to abandon ship; after ten minutes she capsized before sinking at 07:15. Watchers on Cressy had seen the submarine, opened fire and made a failed attempt to ram, then turned to pick up survivors. At 07:20, U-9 fired two torpedoes toward Cressy from her stern torpedo tubes at a range of 1,000 yd (910 m). One torpedo missed and the submarine turned and fired her remaining bow torpedo at 550 yd (500 m). The first torpedo struck the starboard side at around 07:25, the second the port beam at 07:30. The ship capsized to starboard and floated upside down until 07:55.[8]

Two Dutch sailing trawlers in the vicinity declined to close with Cressy for fear of mines.[9][lower-alpha 1] Distress calls had been received by Commodore Tyrwhitt, who, with the destroyer squadron, was already at sea returning to the cruisers, now that the weather had improved. At 08:30, the Dutch steamship Flora approached the scene (having seen the sinkings) and rescued 286 men. A second steamer—Titan—picked up another 147. More were rescued by two Lowestoft sailing trawlers, Coriander and J.G.C., before the destroyers arrived at 10:45, 837 men were rescued while 1,397 men and 62 officers—many of them reservists–were killed, including Robert Johnson, the Captain of Cressy.[11] The destroyers began a search for the submarine, which had little electrical power remaining to travel underwater and could only make 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) on the surface. The submarine submerged for the night before returning home the next day.[12]

Aftermath

The disaster shook public confidence in Britain and the world in the Royal Navy. Other cruisers were withdrawn from patrol duties; Christian was reprimanded and Drummond was criticized by the inquiry for failing to take the anti-submarine precautions recommended by the Admiralty and praised for his conduct during the attack. The 28 officers and 258 men rescued by Flora were landed at IJmuiden and were repatriated on 26 September.[13]

Wenman "Kit" Wykeham-Musgrave (1899–1989) survived being torpedoed on all three ships. His daughter recalled

He went overboard when the Aboukir was going down and he swam like mad to get away from the suction. He was then just getting on board the Hogue and she was torpedoed. He then went and swam to the Cressy and she was also torpedoed. He eventually found a bit of driftwood, became unconscious and was eventually picked up by a Dutch trawler.

— Pru Bailey-Hamilton[14]

Wykeham-Musgrave survived the war and rejoined the Royal Navy in 1939, reaching the rank of commander.[15]

Weddigen and his crew returned to a heroes' welcome; Weddigen was awarded the Iron Cross, 1st Class and his crew each received the Iron Cross, 2nd Class. The sinking of the three ships caused the danger of U-boat attack to be taken more seriously by the Admiralty.[16] Commander Dudley Pound, serving in the Grand Fleet as a commander aboard the battleship St. Vincent (who became First Sea Lord) wrote in his diary on 24 September,

Much as one regrets the loss of life one cannot help thinking that it is a useful warning to us — we had almost begun to consider the German submarines as no good and our awakening which had to come sooner or later and it might have been accompanied by the loss of some of our Battle Fleet.

— Pound[17]

In 1954, the British government sold the salvage rights to the ships and work began in 2011.[18]

Order of battle

Royal Navy

- HMS Aboukir, armoured cruiser, flagship

- HMS Hogue, armoured cruiser

- HMS Cressy, armoured cruiser

German Navy

- U-9, submarine

Notes

Footnotes

- Marder 1965, p. 55; Corbett 2009, p. 31.

- Corbett 2009, p. 171.

- Corbett 2009, pp. 172, 174.

- Corbett 2009, pp. 172–173; Massie 2004, p. 130.

- Corbett 2009, p. 174.

- Corbett 2009, p. 175.

- Massie 2004, pp. 133–134.

- Massie 2004, pp. 134–135.

- Corbett 2009, p. 181.

- Collier 1917, p. 214.

- Corbett 2009, p. 181; NSM 1924, pp. 56, 59.

- Massie 2004, p. 136.

- Corbett 2009, pp. 182–183.

- BBC 2010.

- WHW-M 2010.

- Marder 1965, p. 59.

- Halpern 2003, p. 413.

- Eye 2011, p. 31.

References

Books

- Collier, Chaplain George Henry, RN (1917). "How it Feels to a Clergyman to be Torpedoed on a Man-of-War". In Miller, F. T. (ed.). True Stories of the Great War: Collected in Six Volumes from Authoritative Sources. New York: Review of Reviews. pp. 212–217. OCLC 16880611. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- Corbett, J. S. (2009) [1938]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War based on Official Documents. I (2nd repr. Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Longmans, Green. ISBN 1-84342-489-4. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- Halpern, Paul G. (2003). Duffy, Michael (ed.). The Naval Miscellany. VI. London: Navy Records Society. ISBN 0-7546-3831-6.

- Marder, Arthur J. (1965). From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904–1919: The War Years to the eve of Jutland: 1914–1916. II. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 865180297.

- Massie, Robert K. (2004). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-04092-8.

- Monograph No. 24: Home Waters Part II: September and October 1914 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). XI. London: Naval Staff, Training and Staff Duties Division (HMSO). 1924. OCLC 816503836. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

Journals

- "Booty Trawl". Private Eye. London: Pressdram (1, 302): 31. 2011. ISSN 0032-888X.

Websites

- "BBC Inside Out – Yorkshire Dive". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- "Commander Wenman Humfrey Wykeham-Musgrave". Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

_(14761576186)-_Aboukir_sinking.jpg)