1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt

The 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt[lower-alpha 1] was a failed attempt made by Communist leaders of the Soviet Union to take control of the country from Mikhail Gorbachev, who was Soviet President and General Secretary. The coup leaders were hard-line opponents of Gorbachev's reform program and of the new union treaty that he had negotiated. The treaty decentralized much of the central government's power to the republics. The hard-liners were opposed, mainly in Moscow, by a short but effective campaign of civil resistance[10] led by Russian president Boris Yeltsin, who had been both an ally and critic of Gorbachev. Although the coup collapsed in only two days and Gorbachev returned to power, the event destabilized the USSR and is widely considered to have contributed to both the demise of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the USSR.

| 1991 August Coup Августовский Путч (Avgustovskiy Putch) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the dissolution of the Soviet Union | |||

| |||

| Date | 19 – 22 August 1991 (3 days) | ||

| Location | Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union | ||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of the Soviet Union |

|---|

.svg.png) .svg.png)  |

|

1917–1927: Establishment |

|

1927–1953: Stalinist dictatorship

|

|

1953–1964: Khrushchev Thaw |

|

1964–1985: Era of Stagnation |

|

1985–1991: Perestroika and collapse

|

|

|

After the capitulation of the State Committee on the State of Emergency (GKChP), popularly referred to as the "Gang of Eight", both the Supreme Court of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev described their actions as a coup attempt.

Background

Since assuming power as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1985, Gorbachev had embarked on an ambitious program of reform, embodied in the twin concepts of perestroika and glasnost, meaning economic/political restructuring and openness, respectively.[11] These moves prompted resistance and suspicion on the part of hardline members of the nomenklatura. The reforms also unleashed some forces and movements that Gorbachev did not expect. Specifically, nationalist agitation on the part of the Soviet Union's non-Russian minorities grew, and there were fears that some or all of the union republics might secede. In 1991, the Soviet Union was in a severe economic and political crisis. Scarcity of food, medicine, and other consumables was widespread,[12] people had to stand in long lines to buy even essential goods,[13] fuel stocks were up to 50% less than the estimated need for the approaching winter, and inflation was over 300% per year, with factories lacking in cash needed to pay salaries.[14] In 1990, Estonia,[15] Latvia,[16] Lithuania,[17] Armenia and Georgia had already declared the restoration of their independence from the Soviet Union. In January 1991, there was an attempt to return Lithuania to the Soviet Union by force. About a week later, there was a similar attempt by local pro-Soviet forces to overthrow the Latvian authorities. There were continuing armed ethnic conflicts in Nagorno Karabakh and South Ossetia.

Russia declared its sovereignty on 12 June 1990 and thereafter limited the application of Soviet laws, in particular the laws concerning finance and the economy, on Russian territory. The Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR adopted laws which contradicted Soviet laws (the so-called War of Laws).

In the unionwide referendum on 17 March 1991, boycotted by the Baltic states, Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova, the supermajority of the residents of the rest of the republics expressed the desire to retain the renewed Soviet Union, with 77.85% voting in favor. Following negotiations, eight of the nine republics (except Ukraine) approved the New Union Treaty with some conditions. The treaty would make the Soviet Union a federation of independent republics with a common president, foreign policy, and military. Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan were to sign the Treaty in Moscow on 20 August 1991.

Preparation

On 11 December 1990, KGB Chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov, made a "call for order" over Central television in Moscow.[18] That day, he asked two KGB officers[19] to prepare a plan of measures that could be taken in case a state of emergency was declared in the USSR. Later, Kryuchkov brought Soviet Defense Minister Dmitry Yazov, Internal Affairs Minister Boris Pugo, Premier Valentin Pavlov, Vice-President Gennady Yanayev, Soviet Defense Council deputy chief Oleg Baklanov, Gorbachev secretariat head Valery Boldin, and CPSU Central Committee Secretary Oleg Shenin into the conspiracy.[20][21]

The members of the GKChP hoped that Gorbachev could be persuaded to declare the state of emergency and to "restore order".

On 23 July 1991, a number of party functionaries and literati published in the hardline newspaper Sovetskaya Rossiya a piece entitled A Word to the People which called for decisive action to prevent disastrous calamity.

Six days later, Gorbachev, Russian President Boris Yeltsin and Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev discussed the possibility of replacing such hardliners as Pavlov, Yazov, Kryuchkov and Pugo with more liberal figures. Kryuchkov, who had placed Gorbachev under close surveillance as Subject 110 several months earlier, eventually got wind of the conversation.[22][23][24]

On 4 August, Gorbachev went on holiday to his dacha in Foros, Crimea. He planned to return to Moscow in time for the New Union Treaty signing on 20 August.

On 17 August, the members of the GKChP met at a KGB guesthouse in Moscow and studied the treaty document. They believed the pact would pave the way to the Soviet Union's breakup, and decided that it was time to act. The next day, Baklanov, Boldin, Shenin, and USSR Deputy Defense Minister General Valentin Varennikov flew to Crimea for a meeting with Gorbachev. They demanded that Gorbachev either declare a state of emergency or resign and name Yanayev as acting president to allow the members of the GKChP "to restore order" in the country.[21][25][26]

Gorbachev has always claimed that he refused point blank to accept the ultimatum.[25][27] Varennikov has insisted that Gorbachev said: "Damn you. Do what you want. But report my opinion!"[28] However, those present at the dacha at the time testified that Baklanov, Boldin, Shenin, and Varennikov had been clearly disappointed and nervous after the meeting with Gorbachev.[25] With Gorbachev's refusal, the conspirators ordered that he remain confined to the Foros dacha; at the same time the dacha's communication lines (which were controlled by the KGB) were shut down. Additional KGB security guards were placed at the dacha gates with orders to stop anybody from leaving.

The members of the GKChP ordered 250,000 pairs of handcuffs from a factory in Pskov to be sent to Moscow[29] and 300,000 arrest forms. Kryuchkov doubled the pay of all KGB personnel, called them back from holiday, and placed them on alert. The Lefortovo Prison was emptied to receive prisoners.[23]

The coup chronology

The members of the GKChP met in the Kremlin after Baklanov, Boldin, Shenin and Varennikov returned from Crimea. Yanayev, Pavlov and Baklanov signed the so-called "Declaration of the Soviet Leadership" in which they declared the state of emergency in all of the USSR and announced that the State Committee on the State of Emergency (Государственный Комитет по Чрезвычайному Положению, ГКЧП, or Gosudarstvenniy Komitet po Chrezvichaynomu Polozheniyu, GKChP) had been created "to manage the country and to effectively maintain the regime of the state of emergency". The GKChP included the following members:

- Gennady Yanayev, Vice President

- Valentin Pavlov, Prime Minister

- Vladimir Kryuchkov, Head of the KGB

- Dmitry Yazov, Minister of Defence

- Boris Pugo, Minister of Interior

- Oleg Baklanov, Member of the CPSU Central Committee

- Vasily Starodubtsev, Chairman of the Peasant Union

- Alexander Tizyakov, President of the Association of the State Enterprises and Objects of Industry, Transport, and Communications[26][30]

Yanayev signed the decree naming himself as acting USSR president on the pretext of Gorbachev's inability to perform presidential duties due to "illness".[30] These eight collectively became known as the "Gang of Eight".

The GKChP banned all newspapers in Moscow, except for nine Party-controlled newspapers.[30] The GKChP also issued a populist declaration which stated that "the honour and dignity of the Soviet man must be restored."[30]

19 August

All of the State Committee on the State of Emergency (GKChP) documents were broadcast over the state radio and television starting from 7 a.m. The Russian SFSR-controlled Radio Rossii and Televidenie Rossii, plus "Ekho Moskvy", the only independent political radio station, were cut off the air.[31] Armour units of the Tamanskaya Division and the Kantemirovskaya tank division rolled into Moscow along with paratroops. Four Russian SFSR people's deputies (who were considered the most "dangerous") were detained by the KGB at an army base near Moscow.[20] The conspirators considered detaining Russian SFSR President Boris Yeltsin upon his arrival from a visit to Kazakhstan on 17 August, or after that when he was at his dacha near Moscow, but for an undisclosed reason did not do so. The failure to arrest Yeltsin proved fatal to their plans.[20][32][33]

_(cropped).jpg)

Yeltsin arrived at the White House, Russia's parliament building, at 9 am on Monday 19 August. Together with Russian SFSR Prime Minister Ivan Silayev and Supreme Soviet Chairman Ruslan Khasbulatov, Yeltsin issued a declaration that condemned the GkChP's actions as a reactionary anti-constitutional coup. The military was urged not to take part in the coup. The declaration called for a general strike with the demand to let Gorbachev address the people.[34] This declaration was distributed around Moscow in the form of flyers.

In the afternoon, the citizens of Moscow began to gather around the White House and to erect barricades around it.[34] In response, Gennady Yanayev declared the state of emergency in Moscow at 16:00.[26][30] Yanayev declared at the press conference at 17:00 that Gorbachev was "resting". He said: "Over these years he has got very tired and needs some time to get his health back."[26]

Meanwhile, Major Evdokimov, chief of staff of a tank battalion of the Tamanskaya Division guarding the White House, declared his loyalty to the leadership of the Russian SFSR.[34][35] Yeltsin climbed one of the tanks and addressed the crowd. Unexpectedly, this episode was included in the state media's evening news.[36]

20 August

At noon, Moscow military district commander General Kalinin, whom Yanayev appointed as military commandant of Moscow, declared a curfew in Moscow from 23:00 to 5:00, effective from 20 August.[21][31][34] This was understood as the sign that the attack on the White House was imminent.

The defenders of the White House prepared themselves, most of them being unarmed. Evdokimov's tanks were moved from the White House in the evening.[26][37] The makeshift White House defense headquarters was headed by General Konstantin Kobets, a Russian SFSR people's deputy.[37][38][39]

In the afternoon, Kryuchkov, Yazov and Pugo finally decided to attack the White House. This decision was supported by other GKChP members. Kryuchkov and Yazov's deputies, KGB general Ageyev and Army general Vladislav Achalov, respectively, planned the assault, codenamed "Operation Grom" (Thunder), which would gather elements of the Alpha and Vympel elite special force units, with the support of the paratroopers, Moscow OMON, the Internal Troops of the Dzerzhinsky division, three tank companies and a helicopter squadron. Alpha Group commander General Viktor Karpukhin and other senior officers of the unit together with Airborne Troops deputy commander Gen. Alexander Lebed mingled with the crowds near the White House and assessed the possibility of such an operation. After that, Karpukhin and Vympel commander Colonel Beskov tried to convince Ageyev that the operation would result in bloodshed and should be cancelled.[20][21][22][40] Lebed, with the consent of his immediate superior, Pavel Grachev, returned to the White House and secretly informed the defense headquarters that the attack would begin at 2:00.[22][40]

While the events were unfolding in the capital, Estonia's Supreme Council declared at 23:03 the full reinstatement of the independent status of the Republic of Estonia after 41 years.

21 August

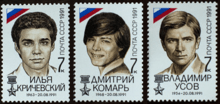

At about 1:00, not far from the White House, trolleybuses and street cleaning machines barricaded a tunnel against oncoming Taman Guards infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs). Three men were killed in the incident, Dmitry Komar, Vladimir Usov, and Ilya Krichevsky, while several others were wounded. Komar, a 22 year old veteran from the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, was shot and crushed trying to cover a moving IFV's observation slit. Usov, a 37 year old economist, was killed by a stray bullet whilst coming to Komar's aid. The crowd set fire to an IFV and Krichevsky, a 28 year old architect, was shot dead as the troops escaped.[41][26][38][42] According to Sergey Parkhomenko, a journalist and democracy campaigner who was in the crowd defending the White House, "Those deaths played a crucial role: Both sides were so horrified that it brought a halt to everything."[43] Alpha Group and Vympel did not move to the White House as had been planned and Yazov ordered the troops to pull out from Moscow.

The troops began to move from Moscow at 8:00. The GKChP members met in the Defence Ministry and, not knowing what to do, decided to send Kryuchkov, Yazov, Baklanov, Tizyakov, Anatoly Lukyanov, and Deputy CPSU General Secretary Vladimir Ivashko to Crimea to meet Gorbachev, who refused to meet them when they arrived. With the dacha's communications to Moscow restored, Gorbachev declared all the GKChP's decisions void and dismissed its members from their state offices. The USSR General Prosecutors Office started the investigation of the coup.[22][34]

During that period, the Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia declared its sovereignty officially completed with a law passed by its deputies, confirming the independence restoration act of 4 May as an official act.[44] In Tallinn, just a day after the restitution of independence, the Tallinn TV Tower was taken over by the Airborne Troops, while the television broadcast was cut off for a while, the radio signal was strong as a handful of Estonian Defence League (the unified paramilitary armed forces of Estonia) members barricaded the entry into signal rooms.[45] In the evening, as news of the failure of the coup reached the republic, the paratroopers departed from the tower and left the capital.

22 August

Gorbachev and the GKChP delegation flew to Moscow, where Kryuchkov, Yazov, and Tizyakov were arrested upon arrival in the early hours. Pugo committed suicide along with his wife the next day. Pavlov, Vasily Starodubtsev, Baklanov, Boldin, and Shenin would be in custody within the next 48 hours.[22]

Aftermath

Since several heads of the regional executive committees supported the GKChP, on 21 August the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR adopted Decision No. 1626-1, which authorized Russian President Boris Yeltsin to appoint heads of regional administrations, although the Russian constitution did not empower the president with such authority.[46] It passed another decision the next day which declared the old imperial colors as Russia's national flag.[46] It eventually replaced the Russian SFSR flag two months later.

On the night of 24 August, the Felix Dzerzhinsky statue in front of the KGB building at Dzerzhinskiy Square (Lubianka) was dismantled, while thousands of Moscow citizens took part in the funeral of Dmitry Komar, Vladimir Usov and Ilya Krichevsky, the three citizens who died in the tunnel incident. Gorbachev posthumously awarded them with the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Yeltsin asked their relatives to forgive him for not being able to prevent their deaths.[22]

End of the CPSU

Gorbachev resigned as CPSU General Secretary on 24 August.[22] Vladimir Ivashko replaced him as acting General Secretary but resigned on 29 August when the Supreme Soviet terminated all Party activities in Soviet territory. Around the same time, Yeltsin decreed the transfer of the CPSU archives to the state archive authorities, as well as nationalizing all CPSU assets in the Russian SFSR (which included not only the headquarters of party committees but also educational institutions, hotels, etc.).[46] Yeltsin decreed the termination and banning of all Party activities on Russian soil as well as the closure of the Central Committee building in Staraya Square.[46]

Dissolution of the Soviet Union

On 24 August, Mikhail Gorbachev created the so-called "Committee for the Operational Management of the Soviet Economy" (Комитет по оперативному управлению народным хозяйством СССР), to replace the USSR Cabinet of Ministers headed by Valentin Pavlov, a GKChP member. Russian prime minister Ivan Silayev headed this committee. On the same day the Verkhovna Rada adopted the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine and called for a referendum on support of the Declaration of Independence. The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, the third most powerful republic in the union, also declared its independence the next day on 25 August which then established the Republic of Belarus.[47]

On 5 September, the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union adopted Soviet Law No. 2392-1 "On the Authorities of the Soviet Union in the Transitional Period" under which the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union had replaced Congress of People's Deputies and was reformed. Two new legislative chambers—the Soviet of the Union (Совет Союза) and the Soviet of Republics (Совет Республик)—replaced the Soviet of the Union and the Soviet of Nationalities (both elected by the USSR Congress of Peoples Deputies). The Soviet of the Union was to be formed by the popularly elected USSR people's deputies. The Soviet of Republics was to include 20 deputies from each union republic plus one deputy to represent each autonomous region of each union republic (both USSR people's deputies and republican people's deputies) delegated by the legislatures of the union republic. Russia was an exception with 52 deputies. However, the delegation of each union republic was to have only one vote in the Soviet of Republics. The laws were to be first adopted by the Soviet of the Union and then by the Soviet of Republics.

Also created was the Soviet State Council (Государственный совет СССР), which included the Soviet President and the presidents of union republics. The "Committee for the Operational Management of the Soviet Economy" was replaced by the USSR Inter-republican Economic Committee (Межреспубликанский экономический комитет СССР), also headed by Ivan Silayev.[48]

On 27 August, the first state became independent, when the Supreme Soviet of Moldova declared the independence of Moldova from the Soviet Union. The Supreme Soviets of Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan did the same on 30 and 31 August respectively. Afterwards, on 6 September the newly created Soviet State Council recognized the independence of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.[49] Estonia had declared re-independence on 20 August, Latvia on the following day, while Lithuania had done so already on 11 March 1990. Three days later, on 9 September the Supreme Soviet of Tajikistan declared the independence of Tajikistan from the Soviet Union. Furthermore, in September over 99% percent of voters in Armenia voted for a referendum approving the Republic's commitment to independence. The immediate aftermath of that vote was the Armenian Supreme Soviet's declaration of independence, issued on 21 September. By 27 October the Supreme Soviet of Turkmenistan declared the independence of Turkmenistan from the Soviet Union. On 1 December Ukraine held a referendum, in which more than 90% of residents supported the Act of Independence of Ukraine.

By November, the only Soviet Republics that had not declared independence were Russia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. That same month, seven republics (Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan) agreed to a new union treaty that would form a confederation called the Union of Sovereign States. However, this confederation never materialized.

On 8 December Boris Yeltsin, Leonid Kravchuk and Stanislav Shushkevich—respectively leaders of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (which adopted that name in August 1991)—as well as the prime ministers of the republics met in Minsk, the capital of Belarus, where they signed the Belavezha Accords. This document declared that the Soviet Union had ceased to exist "as a subject of international law and geopolitical reality." It repudiated the 1922 union treaty that established the Soviet Union, and established the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in the Union's place. On 12 December, the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR ratified the accords and recalled the Russian deputies from the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. Although this has been interpreted as the moment that Russia seceded from the Union, in fact Russia took the line that it was not possible to secede from a state that no longer existed. The lower chamber of the Supreme Soviet, the Council of the Union, was forced to halt its operations, as the departure of the Russian deputies left it without a quorum.

Doubts remained about the legitimacy of the signing that took place on 8 December, since only three republics took part. Thus, on 21 December in Alma-Ata on 21 December, the Alma-Ata Protocol expanded the CIS to include Armenia, Azerbaijan and the five republics of Central Asia. They also pre-emptively accepted Gorbachev's resignation. With 11 of the 12 remaining republics (all except Georgia) having agreed that the Union no longer existed, Gorbachev bowed to the inevitable and said he would resign as soon as the CIS became a reality (Georgia joined the CIS in 1993, only to withdraw in 2008 after conflict between Georgia and Russia; the three Baltic states never joined, instead going on to join the European Union and NATO in 2004.)

On 24 December 1991, the Russian SFSR—now renamed the Russian Federation—with the concurrence of the other republics of the Commonwealth of Independent States, informed the United Nations that it would inherit the Soviet Union's membership in the UN—including the Soviet Union's permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council.[50] No member state of the UN formally objected to this step. The legitimacy of this act has been questioned by some legal scholars as the Soviet Union itself was not constitutionally succeeded by the Russian Federation, but merely dissolved. Others argued that the international community had already established the precedent of recognizing the Soviet Union as the legal successor of the Russian Empire, and so recognizing the Russian Federation as the Soviet Union's successor state was valid.

On 25 December 1991, Gorbachev announced his resignation as Soviet president. The red hammer and sickle flag of the Soviet Union was lowered from the Senate building in the Kremlin and replaced with the tricolor flag of Russia. The next day, 26 December 1991, the Council of Republics, the upper chamber of the Supreme Soviet, formally voted the Soviet Union out of existence (the lower chamber, the Council of the Union, had been left without a quorum after the Russian deputies withdrew), thus ending the life of the world's first and oldest socialist state. All former Soviet embassies became Russian embassies while Russia received the nuclear weapons from the other former republics by 1996. A constitutional crisis occurred in 1993 had been escalated into violence and the new constitution adopted officially abolished the entire Soviet government.

Beginning of radical economic reforms in Russia

On 1 November 1991, the RSFSR Congress of People's Deputies issued Decision No. 1831-1 On the Legal Support of the Economic Reform whereby the Russian president (Boris Yeltsin) was granted the right to issue decrees required for the economic reform even if they contravened the laws. Such decrees entered into force if they were not repealed within 7 days by the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR or its Presidium.[46] Five days later, Boris Yeltsin, in addition to the duties of the President, assumed the duties of the prime minister. Yegor Gaidar became deputy prime minister and simultaneously economic and finance minister. On 15 November 1991 Boris Yeltsin issued Decree No. 213 On the Liberalization of Foreign Economic Activity on the Territory of the RSFSR whereby all Russian companies were allowed to import and to export goods and to acquire foreign currency (previously all foreign trade had been tightly controlled by the state).[46] Following the issuing of Decree No. 213, on 3 December 1991 Boris Yeltsin issued Decree No. 297 On the Measures to Liberalize Prices whereby from 2 January 1992 most previously existing price controls were abolished.[46]

Trial of the members of the GKChP

The GKChP members and their accomplices were charged with treason in the form of a conspiracy aimed at capturing power. However, by the end of 1992 they were all released from custody pending trial. The trial in the Military Chamber of the Russian Supreme Court began on 14 April 1993.[51] On 23 February 1994 the State Duma declared amnesty for all GKChP members and their accomplices, along with the participants of the October 1993 crisis.[46] They all accepted the amnesty, except for General Varennikov, who demanded the continuation of the trial and was finally acquitted on 11 August 1994.[22]

Commemoration of the civilians killed

Thousands of people attended the funeral of Dmitry Komar, Ilya Krichevsky and Vladimir Usov on 24 August 1991. Gorbachev made the three men posthumous Heroes of the Soviet Union, for their bravery "blocking the way to those who wanted to strangle democracy.".[52]

Parliamentary commission

In 1991 the Parliamentary Commission for Investigating Causes and Reasons of the coup attempt was established under Lev Ponomaryov, but in 1992 it was dissolved at Ruslan Khasbulatov's insistence.

International reactions

United States

During his vacation in Kennebunkport, Maine, the President of the United States, George H.W. Bush made a blunt demand for Gorbachev's restoration to power and said the United States did not accept the legitimacy of the self-proclaimed new Soviet Government. He returned to the White House after rushing from his vacation home. Bush then issued a strongly-worded statement that followed a day of consultations with other leaders of the Western alliance and a concerted effort to squeeze the new Soviet leadership by freezing economic aid programs. He decried the coup as a "misguided and illegitimate effort" that "bypasses both Soviet law and the will of the Soviet peoples." President Bush called the overthrow "very disturbing," and he put a hold on U.S. aid to the Soviet Union until the coup was ended.[6][53]

The Bush statement, drafted after a series of meetings with top aides at the White House, was much more forceful than the President's initial reaction that morning in Maine. It was in keeping with a unified Western effort to apply both diplomatic and economic pressure to the group of Soviet officials seeking to gain control of the country.

Former President Ronald Reagan had said:

"I can't believe that the Soviet people will allow a reversal in the progress that they have recently made toward economic and political freedom. Based on my extensive meetings and conversations with him, I am convinced that President Gorbachev had the best interest of the Soviet people in mind. I have always felt that his opposition came from the communist bureaucracy, and I can only hope that enough progress was made that a movement toward democracy will be unstoppable."[6]

On September 2, 1991, the United States re-recognized the independence of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania when Bush delivered the press conference in Kennebunkport.[54]

United Kingdom

The British Prime Minister John Major had expressed feelings in a 1991 interview on behalf of the UK about the coup and said "I think there are many reasons why it failed and a great deal of time and trouble will be spent on analysing that later. There were, I think, a number of things that were significant. I don't think it was terribly well-handled from the point of view of those organising the coup. I think the enormous and unanimous condemnation of the rest of the world publicly of the coup was of immense encouragement to the people resisting it. That is not just my view; that is the view that has been expressed to me by Mr. Shevardnadze, Mr. Yakovlev, President Yeltsin and many others as well to whom I have spoken to the last 48 hours. The moral pressure from the West and the fact that we were prepared to state unequivocally that the coup was illegal and that we wanted the legal government restored, was of immense help in the Soviet Union. I think that did play a part."[55]

Major met with his cabinet that same day on 19 August to deal with the crisis. He added, "There seems little doubt that President Gorbachev has been removed from power by an unconstitutional seizure of power. There are constitutional ways of removing the president of the Soviet Union; they have not been used. I believe that the whole world has a very serious stake in the events currently taking place in the Soviet Union. The reform process there is of vital importance to the world and of most vital importance of course to the Soviet people themselves and I hope that is fully clear. There is a great deal of information we don't yet have, but I would like to make clear above all that we would expect the Soviet Union to respect and honor all the commitments that President Gorbachev has made on its behalf, he said, echoing sentiments from a litany of other Western leaders."[6]

However, the British Government had frozen $80 million in economic aid to Moscow, and the European Community scheduled an emergency meeting in which it was expected to suspend a $1.5 billion aid program.[53]

Other sovereign states

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Supranational bodies and organizations

Further fate of GKChP members

- Gennadiy Yanayev, amnesty of the Russian State Duma of 1994, headed the Department of History and International Relations for the Russian International Academy of Tourism,[61] died in 2010

- Valentin Pavlov, amnesty of the Russian State Duma of 1994 (financial expert for several banks and other financial institutions, chairman of Free Economic Society),[62] died in 2003

- Vladimir Kryuchkov, amnesty of the Russian State Duma of 1994, died in 2007

- Dmitriy Yazov, amnesty of the Russian State Duma of 1994 (adviser to Ministry of Defense and the Academy of General Staff)[63] died in 2020

- Boris Pugo, committed suicide on 22 August 1991[64]

- Oleg Baklanov, amnesty of the Russian State Duma of 1994 (chairman of board of directors for "Rosobshchemash")

- Vasiliy Starodubtsev, freed from arrest in 1992 due to health complications (deputy to the Federation Council of Russia 1993–95, governor of Tula Oblast 1997-2005, member of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation since 2007),[65] died in 2011.

- Alexander Tizyakov, amnesty of the Russian State Duma of 1994 (member of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, founder of series of enterprises such as "Antal" (machine manufacturing), "Severnaya kazna" (insurance company), "Vidikon" (production of electric arc furnace), "Fidelity" (production of fast-moving consumer goods)),[66] died in 2019.

See also

Notes and references

- Ольга Васильева, «Республики во время путча» в сб.статей: «Путч. Хроника тревожных дней». // Издательство «Прогресс», 1991. (in Russian). Accessed 14 June 2009. Archived 17 June 2009.

- Solving Transnistria: Any Optimists Left? by Cristian Urse. p. 58. Available at http://se2.isn.ch/serviceengine/Files/RESSpecNet/57339/ichaptersection_singledocument/7EE8018C-AD17-44B6-8BC2-8171256A7790/en/Chapter_4.pdf

- A party led by the politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky – http://www.lenta.ru/lib/14159799/full.htm. Accessed 13 September 2009. Archived 16 September 2009-.

- "Би-би-си - Россия - Хроника путча. Часть II". news.bbc.co.uk.

- Р. Г. Апресян. Народное сопротивление августовскому путчу (recuperato il 27 novembre 2010 tramite Internet Archive)

- Isherwood, Julian M. (19 August 1991). "World reacts with shock to Gorbachev ouster". United Press International. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- R.C. Gupta. (1997) Collapse of the Soviet Union. p. 57. ISBN 9788185842813,

- "Third Soviet official commits suicide". United Press International. 26 August 1991. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- "THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE CHIEF OF ADMINISTRATION KILLS HIMSELF". Deseret News. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Mark Kramer, "The Dialectics of Empire: Soviet Leaders and the Challenge of Civil Resistance in East-Central Europe, 1968–91", in Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present, Oxford University Press, 2009 pp. 108–09.

- "Gorbachev and Perestroika. Professor Gerhard Rempel, Department of History, Western New England College, 1996-02-02, accessed 2008-07-12". Mars.wnec.edu. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- Sarker, Sunil Kumar (1994). The rise and fall of communism. New Delhi: Atlantic publishers and distributors. p. 94. ISBN 978-8171565153. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- "USSR: The food supply situation" (PDF). CIA.gov.

- Gupta, R.C. (1997). Collapse of the Soviet Union. India: Krishna Prakashan Media. p. 62. ISBN 978-8185842813. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Ziemele (2005). p. 30.

- Ziemele (2005). p. 35.

- Ziemele (2005). pp. 38–40.

- Yevgenia Albats and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia – Past, Present, and Future. 1994. ISBN 0-374-52738-5, pages 276-293.

- KGB Maj. Gen. Vyacheslav Zhizhin and KGB Col. Alexei Yegorov, The State Within a State, p. 276–277.

- "Заключение по материалам расследования роли и участии должностных лиц КГБ СССР в событиях 19-21 августа 1991 года". flb.ru.

- (in Russian) "Novaya Gazeta" No. 51 of 23 July 2001 Archived 15 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine (extracts from the indictment of the conspirators)

- (in Russian) Timeline of the events Archived 27 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine, by Artem Krechnikov, Moscow BBC correspondent

- Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (2000). The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West. Gardners Books. ISBN 0-14-028487-7, pages 513–514.

- The KGB surveillance logbook included every move of Gorbachev and his wife Raisa Gorbacheva, Subject 111, such as "18:30. 111 is in the bathtub."The State Within a State, page 276–277

- (in Russian) Novaya Gazeta No. 59 of 20 August 2001 Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine (extracts from the indictment of the conspirators)

- Kommersant, 18 August 2006 (in Russian)

- "Горбачев: "Я за союз, но не союзное государство"" [Gorbachev: "I am for the union, but not the union state"]. BBC News (in Russian). 16 August 2001.

- "Варенников Валентин Иванович/Неповторимое/Книга 6/Часть 9/Глава 2 — Таинственная Страна". mysteriouscountry.ru.

- Revolutionary Passage by Marc Garcelon p. 159

- "Souz.Info Постановления ГКЧП". souz.info.

- (in Russian) another "Kommersant" article, 18 August 2006

- ""Novaya Gazeta" No. 55 of 6 August 2001 (extracts from the indictment of the conspirators)". Archived from the original on 24 December 2005. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- ""Novaya Gazeta" No. 57 of 13 August 2001 (extracts from the indictment of the conspirators)". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- "Путч. Хроника тревожных дней". old.russ.ru. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2007.

- "Izvestia", 18 August 2006 (in Russian)

- "Moskovskie Novosty", 2001, No.33 "Archived copy" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- (in Russian) "Nezavisimoe Voiennoye Obozrenie", 18 August 2006

- "Усов Владимир Александрович". warheroes.ru.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LsF4c06txHM

- "Argumenty i Facty", 15 August 2001

- "Calls for recognition of 1991 Soviet coup martyrs on 20th anniversary". The Guardian Online. 16 August 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- A Russian site on Ilya Krichevsky "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Accessed 15 August 2009. Archived 17 August 2009.

- "Russia's Brightest Moment: The 1991 Coup That Failed". The Moscow Times. 19 August 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- Supreme Soviet of the Latvian SSR (21 August 1991). "Constitutional law On statehood of the Republic of Latvia" (in Latvian). Latvijas Vēstnesis. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- "Estonica.org - The August coup and Estonian independence (1991)". www.estonica.org.

- Konsultant+ (Russian legal database)

- Fedor, Helen (1995). "Belarus – Prelude to Independence". Belarus: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- "Закон СССР от 05.09.1991 N 2392-1 об органах государственной". pravo.levonevsky.org. Archived from the original on 13 July 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "6 сентября". 5 September 2005.

- "INFCIRC/397 - Note to the Director General from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation". 23 November 2003. Archived from the original on 23 November 2003.

- "Vzgliad", 18 August 2006 (in Russian) Archived 7 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "SOVIET TURMOIL; Moscow Mourns And Exalts Men Killed by Coup". The New York Times. 25 August 1991. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Rosenthal, Andrew (20 August 1991). "THE SOVIET CRISIS; Bush Condemns Soviet Coup And Calls For Its Reversal". The New York Times.

- "SOVIET TURMOIL; Excerpts From Bush's Conference: 'Strong Support' for Baltic Independence". The New York Times. 3 September 1991.

- "Mr Major's Comments on the Soviet Coup - 21st August 1991". johnmajor.co.uk.

- Farnsworth, Clyde H. (25 August 1991). "Canadian Is Attacked for Remarks on Soviet Coup". The New York Times.

- "archives". thestar.com.

- Southerl, Daniel; Southerl, Daniel (23 August 1991). "CHINESE DISSIDENTS HAIL MOSCOW EVENTS" – via washingtonpost.com.

- "archives". thestar.com.

- "Nato's Response Covers All Bases".

- "Gennady Yanayev". 12 October 2010.

- "LA Times", March 2015

- Simon Saradzhyan Coup Leader May Join Defense Team, "The Moscow Times", March 2015

- "Find A Grave", March 2015

- Rupert Cornwell "Vasily Starodubtsev: Politician who tried to topple Gorbachev in 1991", March 2015

- Vladimir Socor "The Jamestown Foundation", March 2015

Bibliography

- Bonnell, Victoria E., and Gregory Freidin. "Televorot: The role of television coverage in Russia's August 1991 coup." Slavic Review 52.4 (1993): 810-838. online

- Matthee, Heinrich. "A breakdown of civil-military relations: the Soviet coup of 1991." Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies 29 (1999): 1-17. online

- Meyer, Stephen M. "How the threat (and the coup) collapsed: the politicization of the soviet military." International Security' 16.3 (1991): 5-38. online

- Varney, Wendy, and Brian Martin. "Lessons from the 1991 Soviet coup." Peace Research 32.1 (2000): 52-68. online

- Vogt, William Charles. "The Soviet coup of August 1991: why it happened, and why it was doomed to fail. Diss. Monterey, California." (Naval Postgraduate School, 1991). online

- Ziemele, Ineta (2005). State Continuity and Nationality: The Baltic States and Russia. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-04-14295-9.

Primary sources

- Gorbachev, Mikhail (1991). The August Coup: The Truth and the Lessons. New York: HarperPerennial. Includes transcript of videotaped statement made 19/20 August 1991 as his Foros dacha.

- Bonnell, Victoria E. and Gregory Freidin, eds. Russia at the Barricades: Eyewitness Accounts of the Moscow Coup (August 1991), (M.E. Sharpe, 1994). Includes the chronology of the coup, photos, and accounts from a broad cross-section of participants and eyewitnesses, including the editors.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1991 coup d'état attempt in the Soviet Union. |

- Voices From An (Attempted) Soviet Coup. 1st person accounts and documents from both sides of the barricades. Compiled and edited by Anya Chernyakhovskaya, Dr John Jirik and Nikolai Lamm.

- IRC logs: Transcript of internet chat from the time of the coup

- TASS transmissions at the time of the coup (captured from short-wave radio transmissions, contains decoding errors)

- Andrew Coyne: Getting to the Roots of a Deserved Failure

- The St. Petersburg Times #696(63), 17 August 2001 The issue of The St. Petersburg Times devoted to the 10th anniversary of the coup attempt.

- The Collapse of Stalinism Chronology of the Coup The USSR in 1991: The Implosion of a Superpower by Dr Robert F. Miller

- Moscow Coup, August 1991, Anonymous: Memories of an anonymous Russian in Wiki Memory Archive

- Personal account and photographs of historian Douglas Smith, eyewitness to the coup

- Vadim Anatov, a programmer for Relcom (the first public ISP in the USSR) on YouTube talking about the role of the Internet in resistance to the coup.

- Adventures of the "Nuclear Briefcase": A Russian Document Analysis, Strategic Insights, Volume III, Issue 9 (September 2004), by Mikhail Tsypkin

- Map of Europe showing areas affected by Soviet Coup Attempt