War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear (known as Guerra del Asiento in Spain) was a conflict between Britain and Spain lasting from 1739 to 1748, mainly in New Granada and among the West Indies of the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. Its name, coined by British historian Thomas Carlyle in 1858,[3] refers to Robert Jenkins, a captain of a British merchant ship, who suffered having his ear severed when Spanish sailors boarded his ship at a time of peace. There is no evidence that supports the stories that the severed ear was exhibited before the British Parliament.

The seeds of conflict began with the injury to Jenkins following the boarding of his vessel by Spanish coast guards in 1731, eight years before the war began. Popular response to the incident was tepid until several years later, when opposition politicians and the British South Sea Company played it up, hoping to spur outrage against Spain, believing that a victorious war would improve Britain's trading opportunities in the Caribbean.[4] In addition, the British wanted to keep pressure on Spain to honour their lucrative asiento contract, which gave British slave traders permission to sell slaves in Spanish America. The Spanish refer to this asiento in their name for this war.[5]

British attacks on Spanish possessions in Central America resulted in high casualties, primarily from disease.[6] After 1742, the war was subsumed by the wider War of the Austrian Succession, which involved most of the powers of Europe. Peace arrived with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748.

Background

The cause of the war is traditionally seen as a dispute between Britain and Spain over access to markets in Spanish America. Historians such as Anderson and Woodfine argue it was one of several issues, including tensions with France and British expansion in North America. They suggest the decisive factor in turning a commercial dispute into war was the domestic political campaign to remove Robert Walpole, long-serving British Prime Minister.[7]

The 18th century economic theory of mercantilism viewed trade as a finite resource; if one country increased its share, it was at the expense of others and wars were often fought over commercial issues.[8] The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht gave British merchants access to markets in Spanish America, including the Asiento de Negros, a monopoly to supply 5,000 slaves a year. Another was the Navio de Permiso, permitting two ships a year to sell 500 tons of goods each in Porto Bello and Veracruz.[9] These rights were assigned to the South Sea Company, acquired by the British government in 1720.[10]

However, trade between Britain and mainland Spain was far more significant. British goods were imported through Cadiz, either for sale locally or re-exported to Spanish colonies, with Spanish dye and wool being sold to England. A leading City of London merchant called the trade ‘the best flower in our garden.’[11] The asiento itself was marginally profitable and has been described as a 'commercial illusion'; between 1717 and 1733, only eight ships were sent from Britain to the Americas.[12] Previous holders made money by carrying smuggled goods that evaded customs duties, demand from Spanish colonists creating a large and profitable black market.[13]

Accepting the trade was too widespread to be stopped, the Spanish authorities used it as an instrument of policy. During the 1727 to 1729 Anglo-Spanish War, French ships carrying contraband were let through, while British ships were stopped and severe restrictions imposed on British merchants in Cadiz. This was reversed during the 1733 to 1735 War of the Polish Succession, when Britain supported Spanish acquisitions in Italy.[14]

The 1729 Treaty of Seville allowed the Spanish to board British vessels trading with the Americas. In 1731, Robert Jenkins claimed his ear was amputated by coast guard officers after they discovered contraband aboard his ship Rebecca. Such incidents were seen as the cost of doing business and were forgotten after the easing of restrictions in 1732.[15] Although an earless Jenkins was exhibited in the House of Commons, and war declared in 1739,[16] the legend that his severed ear was shown to the House of Commons has no basis in fact.[17]

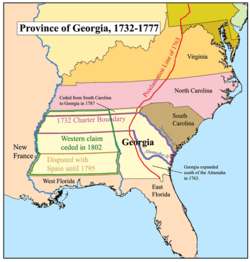

Tensions increased after the founding of the British colony of Georgia in 1732, which Spain considered a threat to Spanish Florida, vital to protect shipping routes with mainland Spain.[18] For their part, the British viewed the 1733 Pacte de Famille between Louis XV and his uncle Philip V as the first step in being replaced by France as Spain's largest trading partner.[19]

A second round of "depredations" in 1738 led to demands for compensation, British newsletters and pamphlets presenting them as inspired by France.[20] Linking these allowed the Tory opposition to imply failure to act was due to George II's concerns over exposing Hanover to French attack. Resistance to European 'entanglements' was an ongoing theme in English politics, going back to the 17th century.[21]

The January 1739 Convention of Pardo set up a Commission to resolve the Georgia-Florida boundary dispute and agreed Spain would pay damages of £95,000 for ships seized. In return, the South Sea Company would pay £68,000 to Philip V as his share of profits on the asiento. Despite being controlled by the government, the company refused and Walpole reluctantly accepted his political opponents wanted war.[22]

On 10 July 1739, the Admiralty was authorised to begin naval operations against Spain and on 20th, a force under Admiral Vernon sailed for the West Indies.[23] He reached Antigua in early October; on 22 October, British ships attacked La Guaira, principal port of the Province of Venezuela and Britain formally declared war on 23 October 1739.[24]

Nomenclature

The incident that gave its name to the war had occurred in 1731, off the coast of Florida, when the British brig Rebecca was boarded by the Spanish patrol boat La Isabela, commanded by the guarda costa (effectively privateer) Juan de León Fandiño. After boarding, Fandiño cut off the left ear of the Rebecca's captain, Robert Jenkins, whom he accused of smuggling (although Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette for 7 October 1731, says it was Lieutenant Dorce).[4] Fandiño told Jenkins, "Go, and tell your King that I will do the same, if he dares to do the same." In March 1738, Jenkins was ordered to testify before Parliament, presumably to repeat his story before a committee of the House of Commons. According to some accounts, he produced the severed ear as part of his presentation, although no detailed record of the hearing exists.[25] The incident was considered alongside various other cases of "Spanish Depredations upon the British Subjects",[26] and was perceived as an insult to Britain's honour and a clear casus belli.[27]

The conflict was named by essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle, in 1858, one hundred and ten years after hostilities ended. Carlyle mentioned the ear in several passages of his History of Friedrich II (1858), most notably in Book XI, chapter VI, where he refers specifically to "the War of Jenkins's Ear".

Conduct of the war

First attack on La Guaira (22 October 1739)

Vernon sent three ships commanded by Captain Thomas Waterhouse to intercept Spanish ships between La Guaira and Porto Bello. He decided to attack a number of vessels that he observed at La Guaira, which was controlled by the Royal Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas.[28] The governor of the Province of Venezuela, Brigadier Don Gabriel de Zuloaga had prepared the port defences, and Spanish troops were well-commanded by Captain Don Francisco Saucedo. On 22 October, Waterhouse entered the port of La Guaira flying the Spanish flag. Expecting attack, the port gunners were not deceived by his ruse; they waited until the British squadron was within range and then simultaneously opened fire. After three hours of heavy shelling, Waterhouse ordered a withdrawal. The battered British squadron sailed to Jamaica to undertake emergency repairs. Trying later to explain his actions, Waterhouse argued that the capture of a few small Spanish vessels would not have justified the loss of his men.

Capture of Portobelo (20–22 November 1739)

Prior to 1739, trade between mainland Spain and its colonies was conducted only through specific ports; twice a year, outward bound ships assembled in Cadiz and the Flota escorted to Portobelo or Veracruz. One way to impact Spanish trade was by attacking or blockading these ports but as many ships carried cargoes financed by foreign merchants, the strategy also risked damaging British and neutral interests.[29]

During the 1727 to 1729 Anglo-Spanish War, the British attempted to take Portobelo but retreated after heavy losses from disease. On 22 November 1739, Vernon attacked the port with six ships of the line; it fell within twenty-four hours and the British occupied the town for three weeks before withdrawing, having first destroyed its fortifications, port and warehouses.[30]

The victory was widely celebrated in Britain; the song "Rule Britannia" was written in 1740 to mark the occasion and performed for the first time at a dinner in London honouring Vernon.[31] The suburb of Portobello in Edinburgh and Portobello Road in London are among the places in Britain named after this success, while more medals were awarded for its capture than any other event in the eighteenth century.[32]

However, taking a port in Spain's American empire was considered a foregone conclusion by many Patriot Whigs and opposition Tories. They now pressed a reluctant Walpole to launch larger naval expeditions to the Gulf of Mexico. In the longer term, the Spanish replaced the twice yearly Flota with a larger number of smaller convoys, calling at more ports and Portobelo's economy did not recover until the building of the Panama Canal nearly two centuries later.

First attack on Cartagena de Indias (13–20 March 1740)

Following the success of Portobelo, Vernon decided to focus his efforts on the capture of Cartagena de Indias in present-day Colombia. Both Vernon and Edward Trelawny, governor of Jamaica, considered the Spanish gold shipping port to be a prime objective. Since the outbreak of the war, and Vernon's arrival in the Caribbean, the British had made a concerted effort to gain intelligence on the defences of Cartagena. In October 1739, Vernon sent First Lieutenant Percival to deliver a letter to Blas de Lezo and Don Pedro Hidalgo, governor of Cartagena. Percival was to use the opportunity to make a detailed study of the Spanish defences. This effort was thwarted when Percival was denied entry to the port.

On 7 March 1740, in a more direct approach, Vernon undertook a reconnaissance-in-force of the Spanish city. Vernon left Port Royal in command of a squadron including ships of the line, two fire ships, three bomb vessels, and transport ships. Reaching Cartagena on 13 March, Vernon immediately landed several men to map the topography and to reconnoitre the Spanish squadron anchored in Playa Grande, west of Cartagena. Having not seen any reaction from the Spanish, on 18 March Vernon ordered the three bomb vessels to open fire on the city. Vernon intended to provoke a response that might give him a better idea of the defensive capabilities of the Spanish. Understanding Vernon's motives, Lezo did not immediately respond. Instead, Lezo ordered the removal of guns from some of his ships, in order to form a temporary shore battery for the purpose of suppressive fire. Vernon next initiated an amphibious assault, but in the face of strong resistance, the attempt to land 400 soldiers was unsuccessful. The British then undertook a three-day naval bombardment of the city. In total, the campaign lasted 21 days. Vernon then withdrew his forces, leaving HMS Windsor Castle and HMS Greenwich in the vicinity, with a mission to intercept any Spanish ship that might approach.

Destruction of the fortress of San Lorenzo el Real Chagres (22–24 March 1740)

After the destruction of Portobelo the previous November, Vernon proceeded to remove the last Spanish stronghold in the area. He attacked the fortress of San Lorenzo el Real Chagres, in present-day Panama on the banks of the Chagres River, near Portobelo. The fort was defended by Spanish patrol boats, and was armed with four guns and about thirty soldiers under Captain of Infantry Don Juan Carlos Gutiérrez Cevallos.

At 3 pm on 22 March 1740, the British squadron, composed of the ships Stafford, Norwich, Falmouth and Princess Louisa, the frigate Diamond, the bomb vessels Alderney, Terrible, and Cumberland, the fireships Success and Eleanor, and transports Goodly and Pompey, under command of Vernon, began to bombard the Spanish fortress. Given the overwhelming superiority of the British forces, Captain Cevallos surrendered the fort on 24 March, after resisting for two days.

Following the strategy previously applied at Porto Bello, the British destroyed the fort and seized the guns along with two Spanish patrol boats.

During this time of British victories along the Caribbean coast, events taking place in Spain would prove to have a significant effect on the outcome of the largest engagement of the war. Spain had decided to replace Don Pedro Hidalgo as governor of Cartagena de Indias. But, the new governor-designate, Lieutenant General of the Royal Armies Sebastián de Eslava y Lazaga had first to dodge the Royal Navy in order to get to his new post. Starting from the Galician port of Ferrol, the vessels Galicia and San Carlos set out on the journey. Hearing the news, Vernon immediately sent four ships to intercept the Spanish. They were unsuccessful in their mission. The Spanish managed to circumvent the British interceptors and entered the port of Cartagena on 21 April 1740, landing there with the new governor and several hundred veteran soldiers.[33]

Second attack on Cartagena de Indias (3 May 1740)

In May, Vernon returned to Cartagena de Indias aboard the flagship HMS Princess Caroline in charge of 13 warships, with the intention of bombarding the city. Lezo reacted by deploying his six ships of the line so that the British fleet was forced into ranges where they could only make short or long shots that were of little value. Vernon withdrew, asserting that the attack was merely a manoeuver. The main consequence of this action was to help the Spanish test their defences.[34]

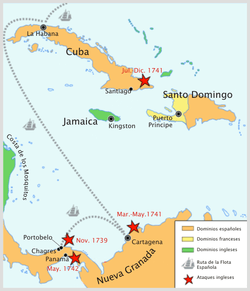

Third attack on Cartagena de Indias (13 March – 20 May 1741)

The largest action of the war was a major amphibious attack launched by the British under Admiral Edward Vernon in March 1741 against Cartagena de Indias, one of Spain's principal gold-trading ports in their colony of New Granada (today Colombia). Vernon's expedition was hampered by inefficient organisation, his rivalry with the commander of his land forces, and the logistical problems of mounting and maintaining a major trans-Atlantic expedition. The strong fortifications in Cartagena and the able strategy of Spanish Commander Blas de Lezo were decisive in repelling the attack. Heavy losses on the British side were due in large part to virulent tropical diseases, primarily an outbreak of yellow fever, which took more lives than were lost in battle.[6]

The extreme ease with which the British destroyed Porto Bello led to a change in British plans. Instead of Vernon concentrating his next attack on Havana as expected, in order to conquer Cuba, he planned to attack Cartagena de Indias. Located in Colombia, it was the main port of the Viceroyalty and main point of the West Indian fleet for sailing to the Iberian Peninsula. In preparation the British gathered in Jamaica one of the largest fleets ever assembled. It consisted of 186 ships (60 more than the famous Spanish Armada of Philip II), bearing 2,620 artillery pieces and more than 27,000 men. Of that number, 10,000 were soldiers responsible for initiating the assault. There were also 12,600 sailors, 1,000 Jamaican slaves and macheteros, and 4,000 recruits from Virginia. The latter were led by Lawrence Washington, the older half-brother of George Washington, future President of the United States.[35]

Colonial officials assigned Admiral Blas de Lezo to defend the fortified city. He was a marine veteran hardened by numerous naval battles in Europe, beginning with the War of the Spanish Succession, and by confrontations with European pirates in the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean, and Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean Sea. Assisting in that effort were Melchor de Navarrete and Carlos Desnaux, with a squadron of six ships of the line (the flagship vessel Galicia together with the San Felipe, San Carlos, África, Dragón, and Conquistador) and a force of 3,000 soldiers, 600 militia and a group of native Indian archers.

Vernon ordered his forces to clear the port of all scuttled ships. On 13 March 1741, he landed a contingent of troops under command of Major General Thomas Wentworth and artillery to take Fort de San Luis de Bocachica. In support of that action, the British ships simultaneously opened with cannon fire, at a rate of 62 shots per hour. In turn, Lezo ordered four of the Spanish ships to aid 500 of his troops defending Desnaux's position, but the Spanish eventually had to retire to the city. Civilians were already evacuating it. After leaving Fort Bocagrande, the Spanish regrouped at Fort San Felipe de Barajas, while Washington's Virginians took up positions in the nearby hill of La Popa. Vernon, believing the victory at hand, sent a message to Jamaica stating that he had taken the city. The report was subsequently forwarded to London, where there was much celebration. Commemorative medals were minted, depicting the defeated Spanish defenders kneeling before Vernon (). The robust image of the enemy depicted in the British medals bore little resemblance to Admiral Lezo. Maimed by years of battle, he was one-eyed and lame, with limited use of one hand.

On the evening of 19 April, the British mounted an assault in force upon Castillo San Felipe de Barajas. Three columns of grenadiers, supported by Jamaicans and several British companies, moved under cover of darkness, with the aid of an intense naval bombardment. The British fought their way to the base of the fort's ramparts where they discovered that the Spanish had dug deep trenches. This effectively rendered the British scaling equipment too short for the task. The British advance was stymied since the fort's walls had not been breached, and the ramparts could not be topped. Neither could the British easily withdraw in the face of intense Spanish fire and under the weight of their own equipment. The Spanish seized on this opportunity, with devastating effect.

Reversing the tide of battle, the Spanish initiated a fixed bayonet charge at first light, inflicting heavy casualties on the British. The surviving British forces retreated to the safety of their ships. The British maintained a naval bombardment, sinking what remained of the small Spanish squadron (after Lezo's decision to scuttle some of his ships in an effort to block the harbour entrance). The Spanish thwarted any British attempt to land another ground assault force. The British troops were forced to remain aboard ship for a month, without sufficient reserves. With supplies running low, and with the outbreak of disease (primarily yellow fever), which took the lives of many on the crowded ships,[36] Vernon was forced to raise the siege on 9 May and return to Jamaica. Six thousand British died while only one thousand Spanish perished.

Vernon carried on, successfully attacking the Spanish at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. On 5 March 1742, with the help of reinforcements from Europe, he launched an assault on Panama City, Panama. In 1742, Vernon was replaced by Rear-Admiral Chaloner Ogle and returned to England, where he gave an accounting to the Admiralty. He learned that he had been elected MP for Ipswich. Vernon maintained his naval career for another four years before retiring in 1746. In an active Parliamentary career, Vernon advocated for improvements in naval procedures. He continued to hold an interest in naval affairs until his death in 1757.

News of the defeat at Cartagena was a significant factor in the downfall of the British Prime Minister Robert Walpole.[37] Walpole's anti-war views were considered by the Opposition to have contributed to his poor prosecution of the war effort. The new government under Lord Wilmington wanted to shift the focus of Britain's war effort away from the Americas and into the Mediterranean. Spanish policy, dictated by the queen Elisabeth Farnese of Parma, also shifted to a European focus, to recover lost Spanish possessions in Italy from the Austrians. In 1742, a large British fleet under Nicholas Haddock was sent to try and intercept a Spanish army being transported from Barcelona to Italy, which he failed to do having only 10 ships.[38] With the arrival of additional ships from Britain in February 1742, Haddock successfully blockaded the Spanish coast[39] failing to force the Spanish fleet into an action. Lawrence Washington survived the yellow fever outbreak, and eventually retired to Virginia. He named his estate Mount Vernon, in honour of his former commander.

Anson expedition

The success of the Porto Bello operation led the British, in September 1740, to send a squadron under Commodore George Anson to attack Spain's possessions in the Pacific. Before they reached the Pacific, numerous men had died from disease, and they were in no shape to launch any sort of attack.[40] Anson reassembled his force in the Juan Fernández Islands, allowing them to recuperate before he moved up the Chilean coast, raiding the small town of Paita. He reached Acapulco too late to intercept the yearly Manila galleon, which had been one of the principal objectives of the expedition. He retreated across the Pacific, running into a storm that forced him to dock for repairs in Canton. After this he tried again the following year to intercept the Manila galleon. He accomplished this on 20 June 1743 off Cape Espiritu Santo, capturing more than a million gold coins.[38]

Anson sailed home, arriving in London more than three and a half years after he had set out, having circumnavigated the globe in the process. Less than a tenth of his forces had survived the expedition. Anson's achievements helped establish his name and wealth in Britain, leading to his appointment as First Lord of the Admiralty.

Florida

In 1740, the inhabitants of Georgia launched an overland attack on the fortified city of St. Augustine in Florida, supported by a British naval blockade, but were repelled. The British forces led by James Oglethorpe, the Governor of Georgia, besieged St. Augustine for over a month before retreating, and abandoned their artillery in the process. The failure of the Royal Navy blockade to prevent supplies reaching the settlement was a crucial factor in the collapse of the siege. Oglethorpe began preparing Georgia for an expected Spanish assault. The Battle of Bloody Mose, where the Spanish and free black forces repelled Oglethorpe's forces at Fort Mose, was also a part of the War of Jenkins' Ear.[41]

French neutrality

When war broke out in 1739, both Britain and Spain expected that France would join the war on the Spanish side. This played a large role in the tactical calculations of the British. If the Spanish and French were to operate together, they would have a superiority of ninety ships of the line.[42] In 1740, there was an invasion scare when it was believed that a French fleet at Brest and a Spanish fleet at Ferrol were about to combine and launch an invasion of England.[43] Although this proved not to be the case, the British kept the bulk of their naval and land forces in southern England to act as a deterrent.

Many in the British government were afraid to launch a major offensive against the Spanish, for fear that a major British victory would draw France into the war to protect the balance of power.[44]

Invasion of Georgia

In 1742, the Spanish launched an attempt to seize the British colony of Georgia. Manuel de Montiano commanded 2,000 troops, who were landed on St Simons Island off the coast. General Oglethorpe rallied the local forces and defeated the Spanish regulars at Bloody Marsh and Gully Hole Creek, forcing them to withdraw. Border clashes between the colonies of Florida and Georgia continued for the next few years, but neither Spain nor Britain undertook offensive operations on the North American mainland.

Second attack on La Guaira (2 March 1743)

The British attacked several locations in the Caribbean with little consequence to the geopolitical situation in the Atlantic. The weakened British forces under Vernon launched an attack against Cuba, landing in Guantánamo Bay with a plan to march the 45 miles to Santiago de Cuba and capture the city.[45] Vernon clashed with the army commander, and the expedition withdrew when faced with heavier Spanish opposition than expected. Vernon remained in the Caribbean until October 1742, before heading back to Britain; he was replaced by admiral Chaloner Ogle, who took command of a sickly fleet. Less than half the sailors were fit for duty. The following year, a smaller fleet of Royal Navy led by commodore Charles Knowles raided the Venezuelan coast, on 2 March 1743 attacking newly La Guaira controlled by Royal Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas whose ships had rendered great assistance to the Spanish navy during War in carrying troops, arms, stores and ammunition from Spain to her colonies, and its destruction would be a severe blow both to the Company and the Spanish Crown.

After a fierce defence by Governor Gabriel José de Zuloaga's troops, Commodore Knowles, having suffered 97 killed and 308 wounded over three days, decided to retire west before sunrise on 6 March. He decided to attack nearby Puerto Cabello. Despite his orders to rendezvous at Borburata Keys—4 miles (6.4 km) east of Puerto Cabello—captains of the detached Burford, Norwich, Assistance, and Otter proceeded to Curaçao. The commodore angrily followed them in. On 28 March, he sent his smaller ships to cruise off Puerto Cabello, and once his main body had been refitted, went to sea again on 31 March. He struggled against contrary winds and currents for two weeks before finally diverting to the eastern tip of Santo Domingo by 19 April.[40]

Merger with wider war

By mid-1742, the War of the Austrian Succession had broken out in Europe. Principally fought by Prussia and Austria over possession of Silesia, the war soon engulfed most of the major powers of Europe, who joined two competing alliances. The scale of this new war dwarfed any of the fighting in the Americas, and drew Britain and Spain's attention back to operations on the European continent. The return of Vernon's fleet in 1742 marked the end of major offensive operations in the War of Jenkins' Ear. France entered the war in 1744, emphasizing the European theatre and planning an ambitious invasion of Britain. While it ultimately failed, the threat persuaded British policymakers of the dangers of sending significant forces to the Americas which might be needed at home.

Britain did not attempt any additional attacks on Spanish possessions. In 1745, William Pepperrell of New England led a colonial expedition, supported by a British fleet under Commodore Peter Warren, against the French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island off Canada. Pepperrell was knighted for his achievement, but Britain returned Louisbourg to the French by the Treaty of Aix-La-Chapelle in 1748. A decade later, during the Seven Years' War (known as the French and Indian War in the North American theatre), British forces under Lord Jeffrey Amherst and General Wolfe recaptured it.[46]

Privateering

The war involved privateering by both sides. Anson captured a valuable Manila galleon, but this was more than offset by the numerous Spanish privateering attacks on British shipping along the transatlantic triangular trade route. They seized hundreds of British ships, looting their goods and slaves, and operated with virtual impunity in the West Indies; they were also active in European waters. The Spanish convoys proved almost unstoppable. During the Austrian phase of the war, the British fleet attacked poorly protected French merchantmen instead.

Lisbon negotiations

From August 1746, negotiations began in the city of Lisbon, in neutral Portugal, to try to arrange a peace settlement. The death of Philip V of Spain had brought his son Ferdinand VI to the throne, and he was more willing to be conciliatory over the issues of trade. However, because of their commitments to their Austrian allies, the British were unable to agree to Spanish demands for territory in Italy and talks broke down.[47]

Aftermath

The eventual diplomatic resolution formed part of the wider settlement of the War of the Austrian Succession by the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle which restored the 'status quo ante'.[48] British territorial and economic ambitions on the Caribbean had been repelled,[49][50][51] while Spain, though unprepared at the start of the war, proved successful in defending their American possessions.[52] Moreover, the war put an end to the British smuggling, and the Spanish fleet was able to dispatch three treasure convoys to Europe during the war and off-balance the British squadron at Jamaica.[53] The issue of the asiento was not mentioned in the treaty, as its importance had lessened for both nations. The issue was finally settled by the 1750 Treaty of Madrid in which Britain agreed to renounce its claim to the asiento in exchange for a payment of £100,000. The South Sea Company ceased its activity, though the treaty also allowed favourable conditions for British trade with Spanish America.[54]

George Anson's expedition to the Southeast Pacific led the Spanish authorities in Lima and Santiago to advance the position of the Spanish Empire in the area. Forts were thus built in the Juan Fernández Islands and the Chonos Archipelago in 1749 and 1750.[55]

Relations between Britain and Spain improved temporarily, in subsequent years, due to a concerted effort by the Duke of Newcastle to cultivate Spain as an ally. A succession of Anglophile ministers were appointed in Spain, including José de Carvajal and Ricardo Wall, all of whom were on good terms with British Ambassador Benjamin Keene, in an effort to avoid a repeat of hostilities. As a result, during the early part of the Seven Years' War between Britain and France, Spain remained neutral. However, it later joined the French and lost both Havana and Manila to the British in 1762, although both were returned as part of the peace settlement.

The War of Jenkins' Ear is commemorated annually on the last Saturday in May at Wormsloe Plantation in Savannah, Georgia.

Citations

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg (1965). A Diplomatic History of the United States. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 8.

- Newman and Brown, p. 744

- Carlyle discusses Jenkins' Ear in several passages of his History of Friedrich II(1858), most notably in Book XI, chap VI, where he refers specifically to "the War of Jenkins's Ear"

- Graboyes, EM; Hullar, TE (2013). "The War of Jenkins' Ear". Otol Neurotol. 34 (2): 368–72. doi:10.1097/mao.0b013e31827c9f7a. PMC 3711623. PMID 23444484.

- Olson, pp. 1121–22

- Webb, pp. 396–398

- James 2001, p. 61.

- Rothbard, Murray (23 April 2010). "Mercantilism as the Economic Side of Absolutism". Mises.org. Good summary of the concept. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Browning 1993, p. 21.

- Ibañez 2008, p. 16.

- Mclachlan 1940, p. 6.

- Anderson 1976, p. 293.

- Richmond 1920.

- Mclachlan 1940, pp. 91-93.

- Woodfine 1998, p. 92.

- Samuel Eliot Morison (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. Oxford University Press. p. 155.

- Harbron 1998, p. 3.

- Ibañez 2008, p. 18.

- McKay 1983, pp. 138–140.

- Mclachlan 1940, pp. 94.

- Shinsuke 2013, pp. 37-39.

- Woodfine 1998, p. 204.

- Davies, Documents 215, 215i

- Rodger 2005, p. 238.

- "I want...a record confirming that Robert Jenkins exhibited his severed ear to Parliament in 1738 (War of Jenkins' Ear)". U.K Parliament Archives: FAQ. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- "Second Parliament of George II:Fourth session (6 of 9, begins 15 March 1738)". British History Online. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- James, p. 59

- "Historical Chronicle" Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Gentleman's Magazine, Saturday 23 October 1739, Vol. 9, October 1739, p. 551; accessed 13 May 2010.

- Lodge 1933, p. 12.

- Rodger 2005, p. 236.

- Rodger 2005, p. 23.

- Simms 2008, p. 276.

- Sáez Abad, p. 57

- Sáez Abad, p. 58

- MVLA archives, document W-734

- Chartrand, Rene. Colonial American Troops, 1610–1774, Vol. 1, pp. 18–19 Osprey Men-at-Arms #366, Osprey Publishing 2002 ISBN 9781841763248

- Browning pp. 109–13.

- Rodger p. 239.

- Reed Browning, The War of the Austrian Succession, p. 97.

- Rodger p. 238.

- branmarc60 (13 June 2018). "Bloody Battle of Fort Mose". Fort Mose Historical Society. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- Browning p. 98.

- Longmate p. 146.

- Simms p. 278.

- Gott p. 39.

- Francis Parkman, A Half Century of Conflict II and Montcalm and Wolfe II

- Lodge pp. 202–07.

- Bemis 1953, p. 8.

- "Spain's fortifications, fleet and merchant marine were able to repel Great Britain's offensive. England's design to detach the Americas from the Spanish monarchy failed, for the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ended the war in 1748, left the Spanish empire intact while cancelling British trading privileges in Spanish territory". Chavez, Thomas E.: Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2004, p. 4. ISBN 9780826327949

- "Naval and continental campaigns had not shattered the Spanish empire nor modified their pretensions to protect their colonies from interlopers. The war had opened with massive expectations of quick victory based on naval power. It ended with failures and disappointments". Harding, Richard: The Emergence of Britain's Global Naval Supremacy: The War of 1739-1748. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2010, p. 6. ISBN 9781843835806

- "The Franco/Spanish alliance still owned most of the Caribbean in terms of geographical area and produced more sugar, the golden crop, than the Anglo/Dutch alliance. The Protestant powers had failed to seize hegemony in the Caribbean from the Catholic powers by the end of the first half of the eighteenth century". Mirza, Rocky M.: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire: A Re-Interpretation of History, Economics and Philosophy: 1492-2006. Oxford: Trafford Publishing, 2007, p. 139. ISBN 9781425113834

- "The Spanish archives reveal that Spain was not prepared for war but willing to take measures to defend her colonies in America. Her men fought well, and for the most part successfully, when the chips were down. That they were aided, in part, by English errors and indecision, should not detract from their victories". Ogelsby, J. C. M.: England vs. Spain in America, 1739-1748: the Spanish Side of the Hill. Historical Papers, 5 (1), 1970, pp. 147–157

- Ogelsby, pp. 156-157

- Simms p. 381.

- Urbina Carrasco, María Ximena (2014). "El frustrado fuerte de Tenquehuen en el archipiélago de los Chonos, 1750: Dimensión chilota de un conflicto hispano-británico". Historia. 47 (I). Retrieved 28 January 2016.

General sources

- Anderson, MS (1976). Europe in the Eighteenth Century, 1713–1783 (A General History of Europe). Longman. ISBN 978-0582486720.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Browning, Reed (1993). The War of the Austrian Succession. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312094836.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Browning, Reed (1975). The Duke of Newcastle. Yale University. ISBN 9780300017465.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dewald, Jonathan, ed. (2003). "History 1450–1789". Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World. Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-31200-X.

- Davies, K. G., ed. (1994). Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series: America and West Indies. HMSO.

- Gott, Richard. Cuba: A new history. Yale University Press, 2005.

- Hakim, Joy (2002). A History of the US. Book 3: From Colonies to Country 1735–1791. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515323-5.

- Harbron, John (1998). Trafalgar and the Spanish Navy: The Spanish Experience of Sea Power. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0870216954.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ibañez, Ignacio Rivas (2008). Mobilizing Resources for War: The Intelligence Systems during the War of Jenkins' Ear. PHD UCL.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James, Lawrence (2001). The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. Abacus. ISBN 0-312-16985-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lodge, Richard (1933). "Presidential Address: The Treaty of Seville (1729)". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 16 (16): 1–43. doi:10.2307/3678662. JSTOR 3678662.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lodge, Sir Richard. Studies in Eighteenth Century Diplomacy 1740–1748. John Murray, 1930.

- McKay, Derek (1983). The Rise of the Great Powers 1648–1815 (First ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0582485549.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mclachlan, Jean O (1940). Trade and Peace with Old Spain (2015 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107585614.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newman, Gerald (1997). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714–1837. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8153-0396-3.

- Olson, James (1996). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-29366-X.

- Pearce, Edward. The Great Man: Sir Robert Walpole Pimlico, 2008.

- Richmond, Herbert (1920). The Navy in the War of 1739–48. War College Series (2015 ed.). War College Series. ISBN 978-1296326296.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rodger, Brendan (2005). The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393060508.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simms, NAM (2008). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, 1714–1783. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140289848.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shinsuke, Satsuma (2013). Britain and Colonial Maritime War in the Early Eighteenth Century. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843838623.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Webb, Stephen (2013). Marlborough's America. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17859-3.

- Woodfine, Philip (1998). Britannia's Glories: The Walpole Ministry and the 1739 War with Spain. Royal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0861932306.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

| Library resources about War of Jenkins' Ear |

- Finucanem Adrian. The Temptations of Trade: Britain, Spain, and the Struggle for Empire (2016)

- Norris, David A. "The War of Jenkins' Ear". History Magazine (Aug/Sep 2015) 16#3 pp. 31–35.

- Ignacio Rivas, Mobilizing Resources for War: The British and Spanish Intelligence Systems in the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–1744) (2010).

Other resources

- Tobias Smollett, "Authentic papers related to the expedition against Carthagena", by Jorge Orlando Melo in Reportaje de la historia de Colombia, Bogotá: Planeta, 1989.

- The American People (sixth edition) by Gary B. Nash and Julie Roy Jeffrey.

- Quintero Saravia, Gonzalo M. (2002). Don Blas de Lezo: defensor de Cartagena de Indias. Editorial Planeta Colombiana, Bogotá, Colombia. ISBN 958-42-0326-6. In Spanish.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to War of Jenkins' Ear. |

- Proposals relating to the war in Georgia and Florida, 1740 – a document suggesting strategies by which General James Oglethorpe might defeat the Spanish during the War of Jenkins' Ear, from the collection of the Georgia Archives.

.svg.png)