Battle of Rocoux

The Battle of Rocoux took place on 11 October 1746 during the War of the Austrian Succession, at Rocourt or Rocoux, near Liège in modern Belgium. It featured a French army under Marshal Saxe and a combined British, Dutch, German and Austrian force led by Charles of Lorraine, John Ligonier and Prince Waldeck. The battle ended the 1746 campaign and the two armies went into winter quarters.

| Battle of Rocoux | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Austrian Succession | |||||||

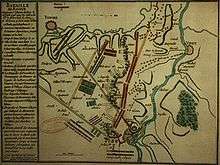

The Battle of Roucoux, 1746 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 80,000 | 120,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7,000 dead and wounded | 3,500 dead and wounded [1] | ||||||

France was struggling to finance the war and opened bilateral peace negotiations with Britain at the Congress of Breda in August 1746. Rocoux was a tactical success that confirmed French control of the Austrian Netherlands but Saxe failed to achieve the decisive victory needed to end the war.

Background

When the War of the Austrian Succession began in 1740, Britain was still fighting the War of Jenkins' Ear with Spain; from 1739 to 1742, the main area of operations was in the Caribbean. British and Dutch troops initially fought as part of the army of Hanover; it was not until March 1744 that France formally declared war on Britain, while the Dutch Republic officially remained neutral until 1747.[2]

French victory at Fontenoy in April 1745 was followed by the capture of the key ports of Ostend, Ghent and Nieuport, while the 1745 Jacobite Rising forced Britain to transfer troops to Scotland. In the first months of 1746, the French took Louvain, Brussels and Antwerp; bolstered by these successes, Foreign Minister d'Argenson sent peace proposals to Britain.[3]

French battlefield victories in Flanders failed to achieve a decisive result, and the British hoped to retrieve their position. With the defeat of the Rising in April, Earl Ligonier returned from Scotland to assume command of the Hanoverian and British troops.[4] However, only British subsidies kept their allies in the war. Austria's priority was to regain Silesia from Prussia; they acquired the Austrian Netherlands in 1713, only because neither the British or Dutch would allow the other to control it. The Dutch also wanted peace, since the fighting badly affected trade; these factors played an important role in the 1746 campaign that ended at Rocoux.[5]

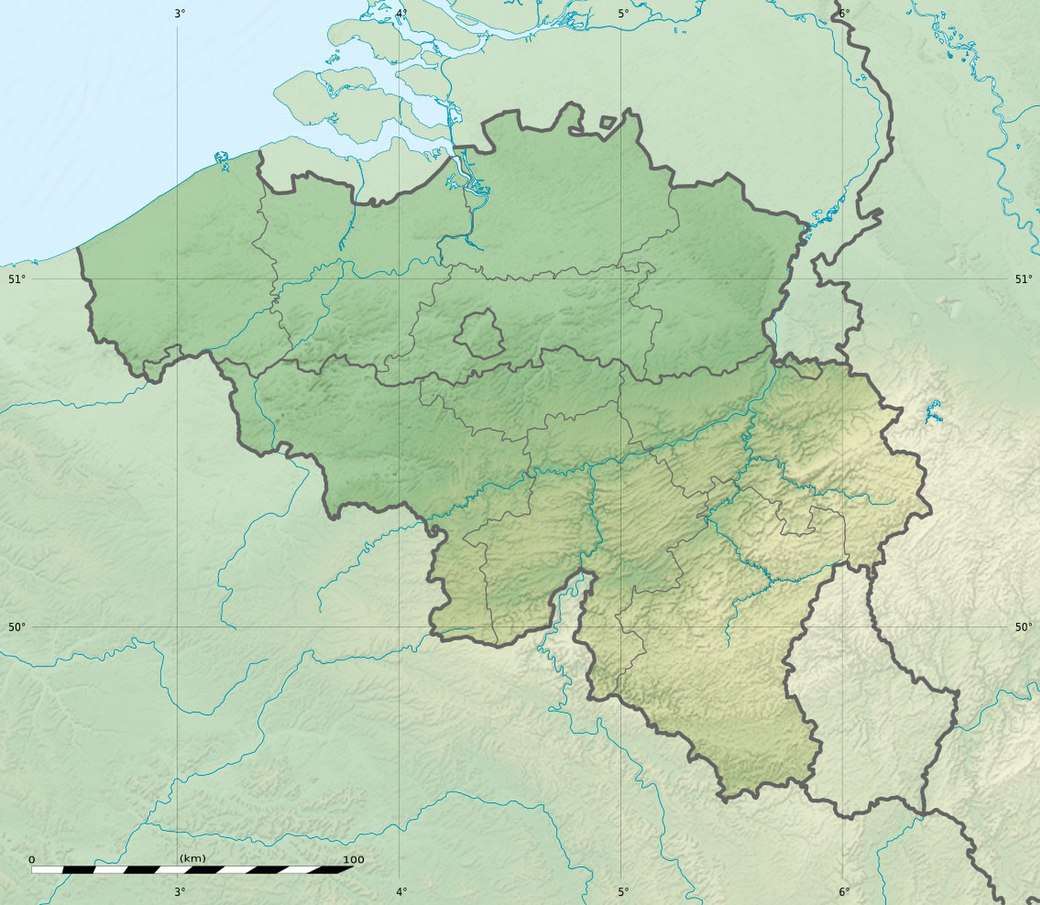

Battle

Often referred to as Flanders, the Austrian Netherlands was a compact area 160 kilometres wide, the highest point only 100 metres above sea level, and dominated by canals and rivers. Until the 19th century, commercial and military goods were largely transported by water and wars in this theatre generally fought for control of rivers such as the Lys, Sambre and Meuse.[6] Between February to July 1746, the French took Brussels, Antwerp, Leuven and Mons, then moved onto those along the Meuse, beginning with Charleroi (see Map).[7]

In mid-July, the Pragmatic Army prepared to defend Namur; leaving the Prince de Conti to finish with Charleroi, Saxe cut their supply lines, forcing them to retreat. By late September, Namur had fallen and the Allies moved to protect Liège, the next town on the Meuse.[8]

Anchored on the left by the Liège suburbs, the Allied line ran through Rocoux to the River Jeker; the Dutch under Waldeck held the left, the British and Germans [lower-alpha 1] in the centre and Austrians on the right. The French army made contact with the Austrian outposts around 18:00 on 10 October; they halted for the night and camped outside Liège. Knowing they were substantially outnumbered, Charles of Lorraine ordered the baggage train across the Meuse to allow an orderly retreat and Ligonier's troops fortified the villages of Rocoux, Varoux and Liers. Saxe decided to attack the Allied left and centre, leaving a small screening force to cover the Austrian sector, which was protected by a series of ditches and ravines.[9]

A night of heavy rain was followed by thick mist, delaying the French until 10:00 am. Their artillery opened fire on the British and Dutch positions, while two columns led by Clermont-Tonnerre and Lowendahl prepared a frontal attack. After the Liège authorities opened the gates, a third under de Contades moved through the town and outflanked Waldeck, who re-aligned his troops to face this threat.[10] These movements meant the French assault did not begin until 15:00; the Dutch put up strong resistance, particularly around the village of Ance, which they finally lost after two hours of heavy fighting.[lower-alpha 2] [11] Counter-attacks by the Dutch cavalry enabled their infantry to pull back in good order.[12]

A second French attack was made against the British-German troops in the centre, who were driven out of their fortified positions in Rocoux and Vercoux, before regrouping further back.[lower-alpha 3][13] Although Von Zastrow retained Liers, the Dutch, British and German infantry withdrew towards the Meuse, covered by the Austrians, who had not been directly engaged. George II later criticised Charles of Lorraine for allegedly failing to support the British and Dutch, but Ligonier said he had acted in accordance with the plan agreed by the Allied leadership the night before.[1]

Saxe decided it was too late in the day to continue the attack, and allowed the Allies to retreat without interference. The British, Germans and Dutch crossed the Meuse on three pontoon bridges; the Austrians withdrew over the Jeker, then made for Maastricht.[1]

Aftermath

Although Rocoux led to the capture of Liège, and opened the way for an attack on the Dutch Republic, it once again failed to achieve a decisive victory. Led by the Marquis de Puisieux, France began bilateral negotiations with Britain at Breda in August 1746. These proceeded slowly, since the British envoy Lord Sandwich was under instructions to delay, hoping their position in Flanders would improve.[14] In the January 1747 Hague Convention, Britain agreed to fund Austrian and Sardinian forces in Italy, and an Allied army of 140,000 in Flanders, increasing to 192,000 in 1748.[15]

However, by late 1746, Austrian forces had expelled Spanish Bourbon troops from Northern Italy and neither France nor Spain could afford to continue funding their campaign. With the removal of this threat, Maria Theresa of Austria wanted peace to restructure her administration and allegedly used her British subsidies to pay for infrastructure projects in Vienna.[16] Hoping to retrieve the position in Flanders, the Duke of Newcastle persuaded his allies to make another attempt, which ended with defeat at Lauffeld in July 1747.[17]

Notes

- Primarily consisting of Hanoverian and Hessian troops

- Extract of a Letter from a Dutch Officer, Relating to the Action near Liege. "The affair that we had yesterday with the French begun in the evening. The fire which the enemy made upon us from their mask'd batteries, and otherwise, was one of the most terrible ever seen, and it look'd as if hell had opened her mouth to swallow us up. As I was of the rear-guard, and among the hindmost of my troop, in retiring from the field of battle, 'tis a miracle I escaped. As the stragglers come in, we hope to make some abatement in the number said to be lost."

- A letter from a Methodist soldier in the Graham's, later 11th Foot reads; "We marched a mile forward into little parks and orchards, a village being between us and our army: here we remained about three hours, while their right wing was engaged with the Dutch, the cannon playing every where all this time. But we were all endued with strength and courage from God, so that the fear of death was taken away from us. And when the French came upon us, and overpowered us, we were troubled at our regiment's giving way, and would have stood our ground, and called to the rest to stop and face the enemy, but to no purpose. In the retreat we were broke; yet after we had retreated about a mile, we rallied twice and fired again. We marched a good part of the night and the next day, about four o'clock, we came to this camp."

References

- Battle of Rocoux.

- Scott 2015, pp. 48–50.

- Lindsay 1957, p. 210.

- Wood 2004.

- Scott 2015, pp. 58–60.

- Childs 1991, pp. 32–33.

- Hochedlinger 2003, p. 259.

- Smollett 1796, p. 193.

- De Périni 1896, p. 322.

- De Périni 1896, pp. 322–323.

- Gentleman's Magazine Vol. XVI, 1746, page 542

- De Périni 1896, p. 327.

- British Journals: Letters on the Battle of Rocoux, 1746.

- Rodger 1993, p. 42.

- Hochedlinger 2003, p. 260.

- Scott 2015, p. 61.

- Scott 2015, p. 62.

Sources

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688–1697: The Operations in the Low Countries (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719089961.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises; Volume VI. Ernest Flammarion, Paris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lindsay, JO (1957). International Relations in The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 7, The Old Regime, 1713–1763:. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521045452.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hochedlinger, Michael (2003). Austria's Wars of Emergence, 1683-1797. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582290846.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rodger, NAM (1993). The Insatiable Earl: A Life of John Montagu, Fourth Earl of Sandwich, 1718-1792. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0099526391.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scott, Hamish (2015). The Birth of a Great Power System, 1740-1815. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138134232.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smollett, Tobias (1796). History of England, from the Revolution to the Death of George III: Volume III. T Capel.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wood, Stephen (2004). "Ligonier, John [formerly Jean-Louis de Ligonier], Earl Ligonier". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16693.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Battle of Rocoux". Britishbattles.com. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- "British Journals: Letters on the Battle of Rocoux, 1746". Kabinettskriege. Retrieved 7 July 2019.