Battle of Mollwitz

The Battle of Mollwitz was fought by Prussia and Austria on 10 April 1741, during the First Silesian War (in the early stages of the War of the Austrian Succession). It was the first battle of the new Prussian King Frederick II, in which both sides made numerous military blunders but Frederick the Great still managed to attain victory. This battle cemented his authority over the newly conquered territory of Silesia and gave him valuable military experience.[4][5]

Background

The War of the Austrian Succession was sparked by the death of Charles VI in 1740 and the succession of his daughter Maria Theresa. The Habsburg Monarchy[lower-alpha 1] was originally subject to Salic law, which excluded women from inheriting it; the 1713 Pragmatic Sanction set this aside, allowing Maria Theresa to succeed her father.[6]

This became a European issue because the Monarchy was the most powerful element in the Holy Roman Empire, a loose federation of mostly German states. This position was threatened by the growing size and power of Bavaria, Prussia and Saxony, as well as Habsburg expansion into lands held by the Ottoman Empire. The Empire was headed by the Holy Roman Emperor; in theory an elected post, it had been held by a Habsburg since 1437. France, Prussia and Saxony now challenged Austrian dominance by nominating Charles of Bavaria as Emperor.[7]

In December 1740, Frederick II seized the opportunity to invade Silesia and begin the First Silesian War. With a population of over one million, the Silesian mining, weaving and dyeing industries produced 10% of total Imperial income.[8] Under Kurt Christoph Graf von Schwerin, the Prussians quickly over-ran most of the province and settled into winter quarters but failed to capture the southern fortresses of Glogau, Breslau, and Brieg.[9] Maria Theresa sent an army of about 20,000 men led by Wilhelm Reinhard von Neipperg to take back the province and assert herself as a strong monarch.[4]

The march north

Neipperg's army caught Frederick II completely off guard as he lingered in the province, and surged northwards past Frederick and his army to relieve the city of Neisse, which was being besieged by a small Prussian force and had not yet fallen. Both Neipperg and Frederick rushed northwards in parallel columns, in a race to reach the city first. In atrocious weather, Neipperg reached Neisse first and set up camp there. Frederick II and his entire army were now caught behind enemy lines with a large Austrian force lying between him and the rest of his kingdom and his supply and communication lines cut off. Both sides knew that battle was now inevitable.

Prussian preparations

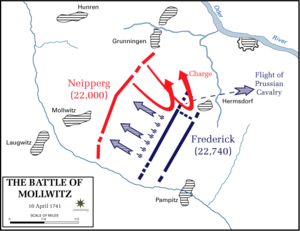

Captured Austrian soldiers told Frederick the exact position of Neipperg's forces at Mollwitz, and the morning fog and snow allowed Frederick's army to advance undetected to within 2000 paces of Neipperg's camp. Most commanders would then have given the order to charge the camp and rout the Austrian army, but since Frederick had never fought a campaign or a battle before, he instead decided to deploy his army in a battle line. There was very heavy snow on the ground which caused snow-blindness, and Frederick miscalculated the distance to the river on his right. He deployed several of his units behind a bend in the river where they could take no part in the battle, and several more units were deployed perpendicular to his two battle lines on the right flank. It is said that Schwerin commented early on that Frederick miscalculated the distance, but he was ignored.[5]

Austrian preparations

Neipperg was in a bad situation when he discovered Frederick's entire army on his doorstep by simply looking out of his window. Not only were most of his soldiers still sleeping, but his entire army was facing to the north-west, away from the Prussians. The Austrian army was waking up, desperately rushing from its camp and trying to form into a cohesive fighting force. By around 1 pm, both sides had formed lines of battle and were ready to engage.

Battle

The Prussian forces advanced on the Austrian line in two sections, but six regiments of Austrian cavalry, numbering 4,500 to 5,000 men and horses, crashed into the cavalry on the right wing of the Prussian Army and shattered it. This left the Prussian flank open to attack, and the Austrian cavalry then turned on the unprotected infantry. Schwerin, the Prussian military commander under Frederick, now advised Frederick II to leave the battlefield because it looked as though the Prussian army was about to be defeated, and the king heeded this warning. Abandoning the field, he was nearly caught and almost shot. Many historians believe that Schwerin advised Frederick to leave so that Schwerin could take command of the troops himself: he was a veteran general.[5]

The scene was chaotic: the perpendicular infantry units deployed between the two Prussian lines were fleeing or firing on other Prussian troops as the Austrian cavalry drove into their flank, but at some point the Prussian infantry, drilled and trained to perfection under Frederick William I, began spontaneously turning right and firing volley after volley at the Austrian cavalry, causing tremendous losses. The leader of the Austrian cavalry, General Römer, received a fatal shot to his head from a Prussian musket ball. With the leaders of both wings dead, an officer asked Schwerin where they should retreat to. Schwerin famously replied, "We'll retreat over the bodies of our enemies", and soon restored the situation on the Prussian right wing.

A second Austrian cavalry attack on the left side was beaten back and Schwerin ordered a general advance of all Prussian forces. The Prussian infantry soon engaged the Austrian battle line. They were some of the most well-drilled infantry of the period, and could fire 4-5 shots a minute with their flintlock muskets, seriously outgunning their opponents. Soon the Austrians were routed from the field and Frederick the Great stood victorious.[4][10]

Aftermath

The victory was due to Field Marshal Schwerin. Frederick the Great had fled from the battlefield when the Austrians seemed to be winning. He later swore never again to leave his troops behind in battle, and he kept this promise faithfully until his death in the late 18th century. He annexed the province of Silesia from Austria and learned a number of valuable lessons from Mollwitz. He is quoted as saying, "Mollwitz was my school". Frederick had made several mistakes but his army still won the battle due to their superior training. From now on he was committed to aggression, and geared his entire army towards an aggressive approach. He gave a standing order that his cavalry commanders would never receive a cavalry charge standing still. He greatly increased the use of light cavalry, Hussars, who would act as skirmishers and scouts. Afterwards he is quoted as saying, "The Prussian army always attacks."[11][12]

Notes

- Often referred to as 'Austria', it included Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, the Austrian Netherlands, and Parma

References

- Duffy: Frederick the Great, 30; Showalter: The wars of Frederick the Great, 45

- Duffy: Frederick the Great, 30

- Duffy: Frederick the Great, 33

- "Battle of Mollwitz". British Battles. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Tim Blanning (29 March 2016). Frederick the Great: King of Prussia. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 104–. ISBN 978-0-8129-8873-4.

- Anderson 1995, p. 3.

- Black 1999, p. 82.

- Armour 2012, pp. 99-101.

- Anderson 1995, pp. 69-72.

- Carl von Clausewitz. "On War, BOOK 5 - CHAPTER 4, Relation of the Three Arms". Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Prof. Chester Verne Easum (12 March 2018). Prince Henry of Prussia, Brother of Frederick the Great. Borodino Books. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-78912-073-8.

- Brian Mooney (15 December 2012). Great Leaders. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-1-4777-0409-7.

Sources

- Anderson, Mark (1995). The War of the Austrian Succession. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582059504.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Armour, Ian (2012). A History of Eastern Europe 1740–1918. Bloomsbury Academic Press. ISBN 978-1849664882.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Black, Jeremy (1999). Britain as a Military Power, 1688-1815. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85728-772-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duffy, Christopher. Frederick the Great: A Military Life. Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1985. ISBN 0-7100-9649-6

- Showalter, Dennis, E. The Wars of Frederick the Great. Longman, 1996. ISBN 0-582-06260-8

- Mooney, Brian, Great Leaders, Rosen publishing, New York, 2013 ISBN 978-1-4777-0409-7

External links

- Obscure Battles: The Battle of Mollwitz 1741