Voyage of the Glorioso

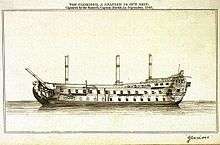

The voyage of the Glorioso involved four naval engagements fought in 1747 during the War of the Austrian Succession between the Spanish 70-gun ship of the line Glorioso and several British squadrons of ships of the line and frigates which tried to capture it. The Glorioso, carrying four million silver dollars from the Americas, was able to repel two British attacks off the Azores and Cape Finisterre, successfully landing her cargo at the port of Corcubión, Spain.

Several days after unloading the cargo, while sailing to Cadiz for repairs, Glorioso was attacked successively near Cape St Vincent by four British privateer frigates and the ships of the line HMS Dartmouth and HMS Russell from Admiral John Byng's fleet. The Dartmouth blew up killing most of her crew, but the 92-gun Russell[4] eventually forced the Glorioso to strike the colours. The British took her to Lisbon, where she had to be broken up because of the extensive damage suffered during the last battle. The commander of the ship, Pedro Messia de la Cerda, and his men, were taken to Great Britain as prisoners, but were considered heroes in Spain and gained the admiration of their enemies. Several British officers were court-martialed and expelled from the Navy for their poor performance against the enemy.[5][6]

The battles

First battle

In July 1747 the Spanish ship of the line Glorioso, launched at Havana on 1740 and under the command of Captain Pedro Messia de la Cerda, was returning to Spain from America, carrying a large shipment of about four million silver dollars, when on 25 July, off the island of Flores, one of the Azores, a British merchant convoy was sighted blurred by the fog. At noon the fog began to dissipate and de la Cerda found that there were ten British ships, three of which were warships: the 60-gun ship of the line Warwick, the 40-gun frigate Lark, and a 20-gun brig.

De la Cerda cleared for action, but he tried to avoid combat, keeping to windward so as not to risk losing the cargo for which he was responsible. The British ships began to pursue the Spanish ship, and at 9:00 p.m. the lighter sloop caught up with the Glorioso and there was an ineffectual exchange of fire between the two. But at 2:00 p.m. there was a squall that took the wind from the Glorioso and allowed the other British ships to come up.

John Crookshanks, commanding officer of the convoy’s escort, sent the brig to protect the merchantmen and ordered HMS Lark to attack the Glorioso. The result of this was that the heavy gunfire from the Spanish ship of the line left the British fifth-rate frigate badly damaged in the hull and the rigging. HMS Warwick then arrived and began to engage the Glorioso, only to be completely dismasted and forced to withdraw. The Glorioso was hit by four cannon balls in the hull, and suffered damage to the rigging. There were five killed (two of whom were civilians) and 44 wounded on the Glorioso.[4] Despite widespread damage, HMS Warwick had only four seamen killed and 20 wounded.[1]

When the British Admiralty was notified about this engagement, Crookshanks was court-martialed for denial of help and negligence in combat. Declared guilty for the defeat, he was dismissed from the Navy, although he was allowed to retain his rank.[7]

Second

After this first engagement, the Glorioso continued sailing to Spain. Some of the damage sustained during the battle could be repaired during the passage, but the more substantial damage needed to be repaired in a port. Despite this the Glorioso was able to repel the attack of three British ships from Admiral John Byng's fleet in sight of Cape Finisterre. These ships were the 50-gun ship of the line HMS Oxford, the 24-gun frigate HMS Shoreham and the 20-gun brig HMS Falcon.[5] After a three-hour-long fight, the three ships had suffered heavy damage, and they were forced to withdraw.[4] Captain Callis of HMS Oxford was later court-martialed, but unlike Commodore Crookshanks, he was honourably acquitted.[8] The Glorioso lost her bowsprit and sustained several casualties, but the next day, 16 August, she finally entered the port of Corcubión, Galicia, and unloaded her cargo.

Third and fourth

In Corcubión, Glorioso’s crew could make the necessary repairs to make the ship seaworthy. After that, Captain de la Cerda decided to head to Ferrol, but contrary winds damaged Glorioso's rigging and the ship was forced instead to make for Cadiz. She initially sailed away from the Portuguese coast to avoid further clashes with British ships. However, on 17 October, she encountered a squadron of four British privateers under Commodore George Walker near Cape Saint Vincent. This squadron, called the 'Royal Family' because of the names of the ships, was composed of the frigates King George, Prince Frederick, Princess Amelia and Duke, altogether carrying 960 men and 120 guns.[9]

At 8 a.m. the King George, flagship of the division, managed to approach the Glorioso and the two ships exchanged fire, with the British frigate losing her mainmast and two guns as a result of Glorioso's first salvo. The Spanish and British ships duelled for three hours, taking heavy damage that forced her to break off contact. The Glorioso continued sailing to the south, being pursued by the three frigates, which were later reinforced by two ships of the line, the 50-gun HMS Dartmouth and the 92-gun HMS Russell.

The captain of the Dartmouth, John Hamilton, managed to place his ship next to the Glorioso; nevertheless after a fierce exchange of fire the British ship caught fire on her powder magazine and blew up at 3:30 PM of 8 October. Captain Hamilton and most of the crew perished in the flames. Only a lieutenant, Christopher O’Brien, and 11 seamen survived the explosion.[10] Some sources mention 14 survivors from a crew of 300.[11] According to one survivor, HMS Dartmouth was already dismasted and heavily damaged by the Spanish gunfire when a round from Glorioso hit the light-room of the magazine, starting a fire that ignited the powder and blew the ship up. He recalled 15 seamen rescued out of a crew of 325.[3] These men were saved by life boats from the Prince Frederick. The three frigates joined the Russell the following evening and together riddled the Glorioso with all their guns. The Spanish ship resisted from midnight to 9 AM, when about to sink, almost completely dismasted, without ammunition, and with 33 men killed and 130 wounded on board, Captain don Pedro Messia de la Cerda, seeing that the defence was impossible, surrendered her. HMS Russell had 12 seamen killed and several wounded.[12] Another eight men died aboard King George.[2]

Aftermath

After the battle the British ships sailed to Lisbon, taking the Glorioso with them. The Spanish ship of the line was surveyed, but not taken into the Royal Navy, and was broken up. Commodore Walker, commander of the four privateer frigates, was severely reprimanded by one of the owners of the Royal Family for risking his ship against a superior enemy. Walker, dissenting, responded:

Had the treasure been aboard the Glorioso, as I expected, my dear sir, your compliment would have been far different. Or had we let her escape from us with the treasure aboard, what would you have said then?

— Commodore George Walker, Lisbon, October, 1747.[13]

Captain de la Cerda and his men, who had been taken on board the Prince Frederick and the King George, were brought to Great Britain and imprisoned in London, where they became the subject of the admiration of their enemies. De la Cerda was later promoted to commodore for his gallant courage in combat and the surviving crew received rewards on their return to Spain. According to some British sources, the defence of the Glorioso ranks foremost in Spanish naval history.[14]

References

- Jefferies, F. (1747). The Gentleman's magazine, Volume 17, p. 508

- Laughton pp. 244-245

- Kimber, Isaac (ed.),(1747). The London magazine, or, Gentleman's monthly intelligencer, Volumen 17, pp. 172-173

- Duro p.341

- Laughton p.240

- Schomberg p.241

- Matcham, Mary Eyre (2009). A Forgotten John Russell Being Letters to a Man of Business 1724-1751. BiblioBazaar, p. 244. ISBN 1-113-72434-X

- Keppel p.121

- Walker p.157

- Beatson pp. 373-374

- Laughton p. 245

- Beatson, p. 374

- Johnston p.235

- Allen p.166

Bibliography

- Allen, Joseph (1852). Battles of the British Navy, Volume 1. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Beatson, Robert (1804). Naval and military memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783, Volume 1. Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme.

- Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1898). Armada española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y de León, tomo VI. Madrid: Est. tipográfico "Sucesores de Rivadeneyra". (in Spanish)

- Johnston, Charles H. L. (2004). Famous Privateersmen and Adventures of the Sea. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4179-2666-4.

- Keppel, Thomas Robert (1842). The life of Augustus, viscount Keppel, admiral of the White, and first Lord of the Admiralty in 1782-3, Volume 1. London: H. Colburn.

- Laughton, John Knox. Armada Studies in Naval History. Biographies. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4021-8125-2.

- Schomberg, Isaac (1815). Naval chronology: or An historical summary of naval and maritime events... From the time of the Romans, to the treaty of peace of Amiens..., Volume 1. London: T. Egerton by C. Roworth.

- Walker, George (1760). The Voyages And Cruises Of Commodore Walker: During the late Spanish and French Wars. In Two Volumes. London: Millar.