Unicode

Unicode is an information technology (IT) standard for the consistent encoding, representation, and handling of text expressed in most of the world's writing systems. The standard is maintained by the Unicode Consortium, and as of March 2020, there is a repertoire of 143,859 characters, with Unicode 13.0 (these characters consist of 143,696 graphic characters and 163 format characters) covering 154 modern and historic scripts, as well as multiple symbol sets and emoji. The character repertoire of the Unicode Standard is synchronized with ISO/IEC 10646, and both are code-for-code identical.

Logo of the Unicode Consortium | |

| Alias(es) | Universal Coded Character Set (UCS) |

|---|---|

| Language(s) | International |

| Standard | Unicode Standard |

| Encoding formats | UTF-8, UTF-16, GB18030 Less common: UTF-32, BOCU, SCSU, UTF-7 |

| Preceded by | ISO/IEC 8859, various others |

The Unicode Standard consists of a set of code charts for visual reference, an encoding method and set of standard character encodings, a set of reference data files, and a number of related items, such as character properties, rules for normalization, decomposition, collation, rendering, and bidirectional text display order (for the correct display of text containing both right-to-left scripts, such as Arabic and Hebrew, and left-to-right scripts).[1]

Unicode's success at unifying character sets has led to its widespread and predominant use in the internationalization and localization of computer software. The standard has been implemented in many recent technologies, including modern operating systems, XML, Java (and other programming languages), and the .NET Framework.

Unicode can be implemented by different character encodings. The Unicode standard defines UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32, and several other encodings are in use. The most commonly used encodings are UTF-8, UTF-16, and UCS-2 (a precursor of UTF-16 without full support for Unicode); GB18030 is standardized in China and implements Unicode fully, while not an official Unicode standard.

UTF-8, the dominant encoding on the World Wide Web (used in over 95% of websites as of 2020, and up to 100% for some languages)[2] uses one byte[note 1] for the first 128 code points, and up to 4 bytes for other characters.[3] The first 128 Unicode code points represent the ASCII characters, which means that any ASCII text is also a UTF-8 text.

UCS-2 uses two bytes (16 bits) for each character but can only encode the first 65,536 code points, the so-called Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP). With 1,112,064 possible Unicode code points corresponding to characters (see below) on 17 planes, and with over 143,000 code points defined as of version 13.0, UCS-2 is only able to represent less than half of all encoded Unicode characters. Therefore, UCS-2 is outdated, though still widely used in software. UTF-16 extends UCS-2, by using the same 16-bit encoding as UCS-2 for the Basic Multilingual Plane, and a 4-byte encoding for the other planes. As long as it contains no code points in the reserved range U+D800–U+DFFF, a UCS-2 text is valid UTF-16 text.

UTF-32 (also referred to as UCS-4) uses four bytes to encode any given codepoint, but not necessarily any given user-perceived character (loosely speaking, a grapheme), since a user-perceived character may be represented by a grapheme cluster (a sequence of multiple codepoints).[4] Like UCS-2, the number of bytes per codepoint is fixed, facilitating character indexing; but unlike UCS-2, UTF-32 is able to encode all Unicode code points. However, because each character uses four bytes, UTF-32 takes significantly more space than other encodings, and is not widely used. Examples of UTF-32 also being variable-length (as all the other encodings), while in a different sense include: "Devanagari kshi is encoded by 4 code points [..] Flag emojis are also grapheme clusters and composed of two code point characters – for example, the flag of Japan"[5] and all "combining character sequences are graphemes, but there are other sequences of code points that are as well; for example \r\n is one."[6][7][8][9]

Origin and development

Unicode has the explicit aim of transcending the limitations of traditional character encodings, such as those defined by the ISO/IEC 8859 standard, which find wide usage in various countries of the world but remain largely incompatible with each other. Many traditional character encodings share a common problem in that they allow bilingual computer processing (usually using Latin characters and the local script), but not multilingual computer processing (computer processing of arbitrary scripts mixed with each other).

Unicode, in intent, encodes the underlying characters—graphemes and grapheme-like units—rather than the variant glyphs (renderings) for such characters. In the case of Chinese characters, this sometimes leads to controversies over distinguishing the underlying character from its variant glyphs (see Han unification).

In text processing, Unicode takes the role of providing a unique code point—a number, not a glyph—for each character. In other words, Unicode represents a character in an abstract way and leaves the visual rendering (size, shape, font, or style) to other software, such as a web browser or word processor. This simple aim becomes complicated, however, because of concessions made by Unicode's designers in the hope of encouraging a more rapid adoption of Unicode.

The first 256 code points were made identical to the content of ISO/IEC 8859-1 so as to make it trivial to convert existing western text. Many essentially identical characters were encoded multiple times at different code points to preserve distinctions used by legacy encodings and therefore, allow conversion from those encodings to Unicode (and back) without losing any information. For example, the "fullwidth forms" section of code points encompasses a full duplicate of the Latin alphabet because Chinese, Japanese, and Korean (CJK) fonts contain two versions of these letters, "fullwidth" matching the width of the CJK characters, and normal width. For other examples, see duplicate characters in Unicode.

History

Based on experiences with the Xerox Character Code Standard (XCCS) since 1980,[10] the origins of Unicode date to 1987, when Joe Becker from Xerox with Lee Collins and Mark Davis from Apple, started investigating the practicalities of creating a universal character set.[11] With additional input from Peter Fenwick and Dave Opstad,[10] Joe Becker published a draft proposal for an "international/multilingual text character encoding system in August 1988, tentatively called Unicode". He explained that "[t]he name 'Unicode' is intended to suggest a unique, unified, universal encoding".[10]

In this document, entitled Unicode 88, Becker outlined a 16-bit character model:[10]

Unicode is intended to address the need for a workable, reliable world text encoding. Unicode could be roughly described as "wide-body ASCII" that has been stretched to 16 bits to encompass the characters of all the world's living languages. In a properly engineered design, 16 bits per character are more than sufficient for this purpose.

His original 16-bit design was based on the assumption that only those scripts and characters in modern use would need to be encoded:[10]

Unicode gives higher priority to ensuring utility for the future than to preserving past antiquities. Unicode aims in the first instance at the characters published in modern text (e.g. in the union of all newspapers and magazines printed in the world in 1988), whose number is undoubtedly far below 214 = 16,384. Beyond those modern-use characters, all others may be defined to be obsolete or rare; these are better candidates for private-use registration than for congesting the public list of generally useful Unicodes.

In early 1989, the Unicode working group expanded to include Ken Whistler and Mike Kernaghan of Metaphor, Karen Smith-Yoshimura and Joan Aliprand of RLG, and Glenn Wright of Sun Microsystems, and in 1990, Michel Suignard and Asmus Freytag from Microsoft and Rick McGowan of NeXT joined the group. By the end of 1990, most of the work on mapping existing character encoding standards had been completed, and a final review draft of Unicode was ready.

The Unicode Consortium was incorporated in California on 3 January 1991,[12] and in October 1991, the first volume of the Unicode standard was published. The second volume, covering Han ideographs, was published in June 1992.

In 1996, a surrogate character mechanism was implemented in Unicode 2.0, so that Unicode was no longer restricted to 16 bits. This increased the Unicode codespace to over a million code points, which allowed for the encoding of many historic scripts (e.g., Egyptian hieroglyphs) and thousands of rarely used or obsolete characters that had not been anticipated as needing encoding. Among the characters not originally intended for Unicode are rarely used Kanji or Chinese characters, many of which are part of personal and place names, making them rarely used, but much more essential than envisioned in the original architecture of Unicode.[13]

The Microsoft TrueType specification version 1.0 from 1992 used the name Apple Unicode instead of Unicode for the Platform ID in the naming table.

Unicode Consortium

The Unicode Consortium is a nonprofit organization that coordinates Unicode's development. Full members include most of the main computer software and hardware companies with any interest in text-processing standards, including Adobe, Apple, Facebook, Google, IBM, Microsoft, Netflix, and SAP SE.[14]

Over the years several countries or government agencies have been members of the Unicode Consortium. Presently only the Ministry of Endowments and Religious Affairs (Oman) is a full member with voting rights.[14]

The Consortium has the ambitious goal of eventually replacing existing character encoding schemes with Unicode and its standard Unicode Transformation Format (UTF) schemes, as many of the existing schemes are limited in size and scope and are incompatible with multilingual environments.

Scripts covered

Unicode covers almost all scripts (writing systems) in current use today.[15][16]

A total of 154 scripts are included in the latest version of Unicode (covering alphabets, abugidas and syllabaries), although there are still scripts that are not yet encoded, particularly those mainly used in historical, liturgical, and academic contexts. Further additions of characters to the already encoded scripts, as well as symbols, in particular for mathematics and music (in the form of notes and rhythmic symbols), also occur.

The Unicode Roadmap Committee (Michael Everson, Rick McGowan, Ken Whistler, V.S. Umamaheswaran[17]) maintain the list of scripts that are candidates or potential candidates for encoding and their tentative code block assignments on the Unicode Roadmap page of the Unicode Consortium Web site. For some scripts on the Roadmap, such as Jurchen and Khitan small script, encoding proposals have been made and they are working their way through the approval process. For others scripts, such as Mayan (besides numbers) and Rongorongo, no proposal has yet been made, and they await agreement on character repertoire and other details from the user communities involved.

Some modern invented scripts which have not yet been included in Unicode (e.g., Tengwar) or which do not qualify for inclusion in Unicode due to lack of real-world use (e.g., Klingon) are listed in the ConScript Unicode Registry, along with unofficial but widely used Private Use Areas code assignments.

There is also a Medieval Unicode Font Initiative focused on special Latin medieval characters. Part of these proposals have been already included into Unicode.

The Script Encoding Initiative, a project run by Deborah Anderson at the University of California, Berkeley was founded in 2002 with the goal of funding proposals for scripts not yet encoded in the standard. The project has become a major source of proposed additions to the standard in recent years.[18]

Versions

Unicode is developed in conjunction with the International Organization for Standardization and shares the character repertoire with ISO/IEC 10646: the Universal Character Set. Unicode and ISO/IEC 10646 function equivalently as character encodings, but The Unicode Standard contains much more information for implementers, covering—in depth—topics such as bitwise encoding, collation and rendering. The Unicode Standard enumerates a multitude of character properties, including those needed for supporting bidirectional text. The two standards do use slightly different terminology.

The Unicode Consortium first published The Unicode Standard in 1991 (version 1.0), and has published new versions on a regular basis since then. The latest version of the Unicode Standard, version 13.0, was released in March 2020, and is available in electronic format from the consortium's website. The last version of the standard that was published completely in book form (including the code charts) was version 5.0 in 2006, but since version 5.2 (2009) the core specification of the standard has been published as a print-on-demand paperback.[19] The entire text of each version of the standard, including the core specification, standard annexes and code charts, is freely available in PDF format on the Unicode website.

In April 2020, Unicode announced that the release of the forthcoming version 14.0 had been postponed by six months from its initial release of March 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[20]

Thus far, the following major and minor versions of the Unicode standard have been published. Update versions, which do not include any changes to character repertoire, are signified by the third number (e.g., "version 4.0.1") and are omitted in the table below.[21]

| Version | Date | Book | Corresponding ISO/IEC 10646 edition | Scripts | Characters | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total[tablenote 1] | Notable additions | |||||

| 1.0.0 | October 1991 | ISBN 0-201-56788-1 (Vol. 1) | 24 | 7,129, not counting 'space' or 33 non-printing characters (7,163 total)[22] | Initial repertoire covers these scripts: Arabic, Armenian, Bengali, Bopomofo, Cyrillic, Devanagari, Georgian, Greek and Coptic, Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Hangul, Hebrew, Hiragana, Kannada, Katakana, Lao, Latin, Malayalam, Oriya, Tamil, Telugu, Thai, and Tibetan.[22] | |

| 1.0.1 | June 1992 | ISBN 0-201-60845-6 (Vol. 2) | 25 | 28,327 (21,204 added; 6 removed) |

The initial set of 20,902 CJK Unified Ideographs is defined.[23] | |

| 1.1 | June 1993 | ISO/IEC 10646-1:1993 | 24 | 34,168 (5,963 added; 89 removed; 33 reclassified as control characters) |

4,306 more Hangul syllables added to original set of 2,350 characters. Tibetan removed.[24] | |

| 2.0 | July 1996 | ISBN 0-201-48345-9 | ISO/IEC 10646-1:1993 plus Amendments 5, 6 and 7 | 25 | 38,885 (11,373 added; 6,656 removed) |

Original set of Hangul syllables removed, and a new set of 11,172 Hangul syllables added at a new location. Tibetan added back in a new location and with a different character repertoire. Surrogate character mechanism defined, and Plane 15 and Plane 16 Private Use Areas allocated.[25] |

| 2.1 | May 1998 | ISO/IEC 10646-1:1993 plus Amendments 5, 6 and 7, as well as two characters from Amendment 18 | 25 | 38,887 (2 added) |

Euro sign and Object Replacement Character added.[26] | |

| 3.0 | September 1999 | ISBN 0-201-61633-5 | ISO/IEC 10646-1:2000 | 38 | 49,194 (10,307 added) |

Cherokee, Ethiopic, Khmer, Mongolian, Burmese, Ogham, Runic, Sinhala, Syriac, Thaana, Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics, and Yi Syllables added, as well as a set of Braille patterns.[27] |

| 3.1 | March 2001 | ISO/IEC 10646-1:2000

ISO/IEC 10646-2:2001 |

41 | 94,140 (44,946 added) |

Deseret, Gothic and Old Italic added, as well as sets of symbols for Western music and Byzantine music, and 42,711 additional CJK Unified Ideographs.[28] | |

| 3.2 | March 2002 | ISO/IEC 10646-1:2000 plus Amendment 1

ISO/IEC 10646-2:2001 |

45 | 95,156 (1,016 added) |

Philippine scripts Buhid, Hanunó'o, Tagalog, and Tagbanwa added.[29] | |

| 4.0 | April 2003 | ISBN 0-321-18578-1 | ISO/IEC 10646:2003 | 52 | 96,382 (1,226 added) |

Cypriot syllabary, Limbu, Linear B, Osmanya, Shavian, Tai Le, and Ugaritic added, as well as Hexagram symbols.[30] |

| 4.1 | March 2005 | ISO/IEC 10646:2003 plus Amendment 1 | 59 | 97,655 (1,273 added) |

Buginese, Glagolitic, Kharoshthi, New Tai Lue, Old Persian, Syloti Nagri, and Tifinagh added, and Coptic was disunified from Greek. Ancient Greek numbers and musical symbols were also added.[31] | |

| 5.0 | July 2006 | ISBN 0-321-48091-0 | ISO/IEC 10646:2003 plus Amendments 1 and 2, as well as four characters from Amendment 3 | 64 | 99,024 (1,369 added) |

Balinese, Cuneiform, N'Ko, Phags-pa, and Phoenician added.[32] |

| 5.1 | April 2008 | ISO/IEC 10646:2003 plus Amendments 1, 2, 3 and 4 | 75 | 100,648 (1,624 added) |

Carian, Cham, Kayah Li, Lepcha, Lycian, Lydian, Ol Chiki, Rejang, Saurashtra, Sundanese, and Vai added, as well as sets of symbols for the Phaistos Disc, Mahjong tiles, and Domino tiles. There were also important additions for Burmese, additions of letters and Scribal abbreviations used in medieval manuscripts, and the addition of Capital ẞ.[33] | |

| 5.2 | October 2009 | ISBN 978-1-936213-00-9 | ISO/IEC 10646:2003 plus Amendments 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 | 90 | 107,296 (6,648 added) |

Avestan, Bamum, Egyptian hieroglyphs (the Gardiner Set, comprising 1,071 characters), Imperial Aramaic, Inscriptional Pahlavi, Inscriptional Parthian, Javanese, Kaithi, Lisu, Meetei Mayek, Old South Arabian, Old Turkic, Samaritan, Tai Tham and Tai Viet added. 4,149 additional CJK Unified Ideographs (CJK-C), as well as extended Jamo for Old Hangul, and characters for Vedic Sanskrit.[34] |

| 6.0 | October 2010 | ISBN 978-1-936213-01-6 | ISO/IEC 10646:2010 plus the Indian rupee sign | 93 | 109,384 (2,088 added) |

Batak, Brahmi, Mandaic, playing card symbols, transport and map symbols, alchemical symbols, emoticons and emoji. 222 additional CJK Unified Ideographs (CJK-D) added.[35] |

| 6.1 | January 2012 | ISBN 978-1-936213-02-3 | ISO/IEC 10646:2012 | 100 | 110,116 (732 added) |

Chakma, Meroitic cursive, Meroitic hieroglyphs, Miao, Sharada, Sora Sompeng, and Takri.[36] |

| 6.2 | September 2012 | ISBN 978-1-936213-07-8 | ISO/IEC 10646:2012 plus the Turkish lira sign | 100 | 110,117 (1 added) |

Turkish lira sign.[37] |

| 6.3 | September 2013 | ISBN 978-1-936213-08-5 | ISO/IEC 10646:2012 plus six characters | 100 | 110,122 (5 added) |

5 bidirectional formatting characters.[38] |

| 7.0 | June 2014 | ISBN 978-1-936213-09-2 | ISO/IEC 10646:2012 plus Amendments 1 and 2, as well as the Ruble sign | 123 | 112,956 (2,834 added) |

Bassa Vah, Caucasian Albanian, Duployan, Elbasan, Grantha, Khojki, Khudawadi, Linear A, Mahajani, Manichaean, Mende Kikakui, Modi, Mro, Nabataean, Old North Arabian, Old Permic, Pahawh Hmong, Palmyrene, Pau Cin Hau, Psalter Pahlavi, Siddham, Tirhuta, Warang Citi, and Dingbats.[39] |

| 8.0 | June 2015 | ISBN 978-1-936213-10-8 | ISO/IEC 10646:2014 plus Amendment 1, as well as the Lari sign, nine CJK unified ideographs, and 41 emoji characters[40] | 129 | 120,672 (7,716 added) |

Ahom, Anatolian hieroglyphs, Hatran, Multani, Old Hungarian, SignWriting, 5,771 CJK unified ideographs, a set of lowercase letters for Cherokee, and five emoji skin tone modifiers[41] |

| 9.0 | June 2016 | ISBN 978-1-936213-13-9 | ISO/IEC 10646:2014 plus Amendments 1 and 2, as well as Adlam, Newa, Japanese TV symbols, and 74 emoji and symbols[42] | 135 | 128,172 (7,500 added) |

Adlam, Bhaiksuki, Marchen, Newa, Osage, Tangut, and 72 emoji[43][44] |

| 10.0 | June 2017 | ISBN 978-1-936213-16-0 | ISO/IEC 10646:2017 plus 56 emoji characters, 285 hentaigana characters, and 3 Zanabazar Square characters[45] | 139 | 136,690 (8,518 added) |

Zanabazar Square, Soyombo, Masaram Gondi, Nüshu, hentaigana (non-standard hiragana), 7,494 CJK unified ideographs, and 56 emoji |

| 11.0 | June 2018 | ISBN 978-1-936213-19-1 | ISO/IEC 10646:2017 plus Amendment 1, as well as 46 Mtavruli Georgian capital letters, 5 CJK unified ideographs, and 66 emoji characters.[46] | 146 | 137,374 (684 added) |

Dogra, Georgian Mtavruli capital letters, Gunjala Gondi, Hanifi Rohingya, Indic Siyaq numbers, Makasar, Medefaidrin, Old Sogdian and Sogdian, Mayan numerals, 5 urgently needed CJK unified ideographs, symbols for xiangqi (Chinese chess) and star ratings, and 145 emoji[47] |

| 12.0 | March 2019 | ISBN 978-1-936213-22-1 | ISO/IEC 10646:2017 plus Amendments 1 and 2, as well as 62 additional characters.[48] | 150 | 137,928 (554 added) |

Elymaic, Nandinagari, Nyiakeng Puachue Hmong, Wancho, Miao script additions for several Miao and Yi dialects in China, hiragana and katakana small letters for writing archaic Japanese, Tamil historic fractions and symbols, Lao letters for Pali, Latin letters for Egyptological and Ugaritic transliteration, hieroglyph format controls, and 61 emoji[49] |

| 12.1 | May 2019 | ISBN 978-1-936213-25-2 | 150 | 137,929 (1 added) |

Adds a single character at U+32FF for the square ligature form of the name of the Reiwa era.[50] | |

| 13.0 | March 2020 | ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 | ISO/IEC 10646:2020[51] | 154 | 143,859 (5,930 added) |

Chorasmian, Dives Akuru, Khitan small script, Yezidi, 4,969 CJK unified ideographs added (including 4,939 in Ext. G), Arabic script additions used to write Hausa, Wolof, and other languages in Africa and other additions used to write Hindko and Punjabi in Pakistan, Bopomofo additions used for Cantonese, Creative Commons license symbols, graphic characters for compatibility with teletext and home computer systems from the 1970s and 1980s, and 55 emoji[52] |

- The number of characters listed for each version of Unicode is the total number of graphic and format characters (i.e., excluding private-use characters, control characters, noncharacters and surrogate code points).

Architecture and terminology

The Unicode Standard defines a codespace[53] of numerical values ranging from 0 through 10FFFF16,[54] called code points[55] and denoted as U+0000 through U+10FFFF ("U+" plus the code point value in hexadecimal, prepended with leading zeros as necessary to result in a minimum of four digits, e. g., U+00F7 for the division sign, ÷, versus U+13254 for the Egyptian hieroglyph designating a reed shelter or a winding wall ( ![]()

Code point planes and blocks

The Unicode codespace is divided into seventeen planes, numbered 0 to 16:

All code points in the BMP are accessed as a single code unit in UTF-16 encoding and can be encoded in one, two or three bytes in UTF-8. Code points in Planes 1 through 16 (supplementary planes) are accessed as surrogate pairs in UTF-16 and encoded in four bytes in UTF-8.

Within each plane, characters are allocated within named blocks of related characters. Although blocks are an arbitrary size, they are always a multiple of 16 code points and often a multiple of 128 code points. Characters required for a given script may be spread out over several different blocks.

General Category property

Each code point has a single General Category property. The major categories are denoted: Letter, Mark, Number, Punctuation, Symbol, Separator and Other. Within these categories, there are subdivisions. In most cases other properties must be used to sufficiently specify the characteristics of a code point. The possible General Categories are:

| General Category (Unicode Character Property)[lower-alpha 1] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Category Major, minor | Basic type[lower-alpha 2] | Character assigned[lower-alpha 2] | Count (as of 13.0) | Remarks |

| Letter (L) | |||||

| Lu | Letter, uppercase | Graphic | Character | 1,791 | |

| Ll | Letter, lowercase | Graphic | Character | 2,155 | |

| Lt | Letter, titlecase | Graphic | Character | 31 | Ligatures containing uppercase followed by lowercase letters (e.g., Dž, Lj, Nj, and Dz) |

| Lm | Letter, modifier | Graphic | Character | 260 | A modifier letter |

| Lo | Letter, other | Graphic | Character | 127,004 | An ideograph or a letter in a unicase alphabet |

| Mark (M) | |||||

| Mn | Mark, nonspacing | Graphic | Character | 1,839 | |

| Mc | Mark, spacing combining | Graphic | Character | 443 | |

| Me | Mark, enclosing | Graphic | Character | 13 | |

| Number (N) | |||||

| Nd | Number, decimal digit | Graphic | Character | 650 | All these, and only these, have Numeric Type = De[lower-alpha 3] |

| Nl | Number, letter | Graphic | Character | 236 | Numerals composed of letters or letterlike symbols (e.g., Roman numerals) |

| No | Number, other | Graphic | Character | 895 | E.g., vulgar fractions, superscript and subscript digits |

| Punctuation (P) | |||||

| Pc | Punctuation, connector | Graphic | Character | 10 | Includes "_" underscore |

| Pd | Punctuation, dash | Graphic | Character | 25 | Includes several hyphen characters |

| Ps | Punctuation, open | Graphic | Character | 75 | Opening bracket characters |

| Pe | Punctuation, close | Graphic | Character | 73 | Closing bracket characters |

| Pi | Punctuation, initial quote | Graphic | Character | 12 | Opening quotation mark. Does not include the ASCII "neutral" quotation mark. May behave like Ps or Pe depending on usage |

| Pf | Punctuation, final quote | Graphic | Character | 10 | Closing quotation mark. May behave like Ps or Pe depending on usage |

| Po | Punctuation, other | Graphic | Character | 593 | |

| Symbol (S) | |||||

| Sm | Symbol, math | Graphic | Character | 948 | Mathematical symbols (e.g., +, −, =, ×, ÷, √, ∊, ≠). Does not include parentheses and brackets, which are in categories Ps and Pe. Also does not include !, *, -, or /, which despite frequent use as mathematical operators, are primarily considered to be "punctuation". |

| Sc | Symbol, currency | Graphic | Character | 62 | Currency symbols |

| Sk | Symbol, modifier | Graphic | Character | 123 | |

| So | Symbol, other | Graphic | Character | 6,431 | |

| Separator (Z) | |||||

| Zs | Separator, space | Graphic | Character | 17 | Includes the space, but not TAB, CR, or LF, which are Cc |

| Zl | Separator, line | Format | Character | 1 | Only U+2028 LINE SEPARATOR (LSEP) |

| Zp | Separator, paragraph | Format | Character | 1 | Only U+2029 PARAGRAPH SEPARATOR (PSEP) |

| Other (C) | |||||

| Cc | Other, control | Control | Character | 65 (will never change)[lower-alpha 3] | No name,[lower-alpha 4] <control> |

| Cf | Other, format | Format | Character | 161 | Includes the soft hyphen, joining control characters (zwnj and zwj), control characters to support bi-directional text, and language tag characters |

| Cs | Other, surrogate | Surrogate | Not (but abstract) | 2,048 (will never change)[lower-alpha 3] | No name,[lower-alpha 4] <surrogate> |

| Co | Other, private use | Private-use | Not (but abstract) | 137,468 total (will never change)[lower-alpha 3] (6,400 in BMP, 131,068 in Planes 15–16) | No name,[lower-alpha 4] <private-use> |

| Cn | Other, not assigned | Noncharacter | Not | 66 (will never change)[lower-alpha 3] | No name,[lower-alpha 4] <noncharacter> |

| Reserved | Not | 830,606 | No name,[lower-alpha 4] <reserved> | ||

| |||||

Code points in the range U+D800–U+DBFF (1,024 code points) are known as high-surrogate code points, and code points in the range U+DC00–U+DFFF (1,024 code points) are known as low-surrogate code points. A high-surrogate code point followed by a low-surrogate code point form a surrogate pair in UTF-16 to represent code points greater than U+FFFF. These code points otherwise cannot be used (this rule is ignored often in practice especially when not using UTF-16).

A small set of code points are guaranteed never to be used for encoding characters, although applications may make use of these code points internally if they wish. There are sixty-six of these noncharacters: U+FDD0–U+FDEF and any code point ending in the value FFFE or FFFF (i.e., U+FFFE, U+FFFF, U+1FFFE, U+1FFFF, ... U+10FFFE, U+10FFFF). The set of noncharacters is stable, and no new noncharacters will ever be defined.[57] Like surrogates, the rule that these cannot be used is often ignored, although the operation of the byte order mark assumes that U+FFFE will never be the first code point in a text.

Excluding surrogates and noncharacters leaves 1,111,998 code points available for use.

Private-use code points are considered to be assigned characters, but they have no interpretation specified by the Unicode standard[58] so any interchange of such characters requires an agreement between sender and receiver on their interpretation. There are three private-use areas in the Unicode codespace:

- Private Use Area: U+E000–U+F8FF (6,400 characters),

- Supplementary Private Use Area-A: U+F0000–U+FFFFD (65,534 characters),

- Supplementary Private Use Area-B: U+100000–U+10FFFD (65,534 characters).

Graphic characters are characters defined by Unicode to have particular semantics, and either have a visible glyph shape or represent a visible space. As of Unicode 13.0 there are 143,696 graphic characters.

Format characters are characters that do not have a visible appearance, but may have an effect on the appearance or behavior of neighboring characters. For example, U+200C ZERO WIDTH NON-JOINER and U+200D ZERO WIDTH JOINER may be used to change the default shaping behavior of adjacent characters (e.g., to inhibit ligatures or request ligature formation). There are 163 format characters in Unicode 13.0.

Sixty-five code points (U+0000–U+001F and U+007F–U+009F) are reserved as control codes, and correspond to the C0 and C1 control codes defined in ISO/IEC 6429. U+0009 (Tab), U+000A (Line Feed), and U+000D (Carriage Return) are widely used in Unicode-encoded texts. In practice the C1 code points are often improperly-translated (mojibake) as the legacy Windows-1252 characters used by some English and Western European texts.

Graphic characters, format characters, control code characters, and private use characters are known collectively as assigned characters. Reserved code points are those code points which are available for use, but are not yet assigned. As of Unicode 13.0 there are 830,606 reserved code points.

Abstract characters

The set of graphic and format characters defined by Unicode does not correspond directly to the repertoire of abstract characters that is representable under Unicode. Unicode encodes characters by associating an abstract character with a particular code point.[59] However, not all abstract characters are encoded as a single Unicode character, and some abstract characters may be represented in Unicode by a sequence of two or more characters. For example, a Latin small letter "i" with an ogonek, a dot above, and an acute accent, which is required in Lithuanian, is represented by the character sequence U+012F, U+0307, U+0301. Unicode maintains a list of uniquely named character sequences for abstract characters that are not directly encoded in Unicode.[60]

All graphic, format, and private use characters have a unique and immutable name by which they may be identified. This immutability has been guaranteed since Unicode version 2.0 by the Name Stability policy.[57] In cases where the name is seriously defective and misleading, or has a serious typographical error, a formal alias may be defined, and applications are encouraged to use the formal alias in place of the official character name. For example, U+A015 ꀕ YI SYLLABLE WU has the formal alias YI SYLLABLE ITERATION MARK, and U+FE18 ︘ PRESENTATION FORM FOR VERTICAL RIGHT WHITE LENTICULAR BRAKCET (sic) has the formal alias PRESENTATION FORM FOR VERTICAL RIGHT WHITE LENTICULAR BRACKET.[61]

Ready-made versus composite characters

Unicode includes a mechanism for modifying characters that greatly extends the supported glyph repertoire. This covers the use of combining diacritical marks that may be added after the base character by the user. Multiple combining diacritics may be simultaneously applied to the same character. Unicode also contains precomposed versions of most letter/diacritic combinations in normal use. These make conversion to and from legacy encodings simpler, and allow applications to use Unicode as an internal text format without having to implement combining characters. For example, é can be represented in Unicode as U+0065 (LATIN SMALL LETTER E) followed by U+0301 (COMBINING ACUTE ACCENT), but it can also be represented as the precomposed character U+00E9 (LATIN SMALL LETTER E WITH ACUTE). Thus, in many cases, users have multiple ways of encoding the same character. To deal with this, Unicode provides the mechanism of canonical equivalence.

An example of this arises with Hangul, the Korean alphabet. Unicode provides a mechanism for composing Hangul syllables with their individual subcomponents, known as Hangul Jamo. However, it also provides 11,172 combinations of precomposed syllables made from the most common jamo.

The CJK characters currently have codes only for their precomposed form. Still, most of those characters comprise simpler elements (called radicals), so in principle Unicode could have decomposed them as it did with Hangul. This would have greatly reduced the number of required code points, while allowing the display of virtually every conceivable character (which might do away with some of the problems caused by Han unification). A similar idea is used by some input methods, such as Cangjie and Wubi. However, attempts to do this for character encoding have stumbled over the fact that Chinese characters do not decompose as simply or as regularly as Hangul does.

A set of radicals was provided in Unicode 3.0 (CJK radicals between U+2E80 and U+2EFF, KangXi radicals in U+2F00 to U+2FDF, and ideographic description characters from U+2FF0 to U+2FFB), but the Unicode standard (ch. 12.2 of Unicode 5.2) warns against using ideographic description sequences as an alternate representation for previously encoded characters:

This process is different from a formal encoding of an ideograph. There is no canonical description of unencoded ideographs; there is no semantic assigned to described ideographs; there is no equivalence defined for described ideographs. Conceptually, ideographic descriptions are more akin to the English phrase "an 'e' with an acute accent on it" than to the character sequence <U+0065, U+0301>.

Ligatures

Many scripts, including Arabic and Devanāgarī, have special orthographic rules that require certain combinations of letterforms to be combined into special ligature forms. The rules governing ligature formation can be quite complex, requiring special script-shaping technologies such as ACE (Arabic Calligraphic Engine by DecoType in the 1980s and used to generate all the Arabic examples in the printed editions of the Unicode Standard), which became the proof of concept for OpenType (by Adobe and Microsoft), Graphite (by SIL International), or AAT (by Apple).

Instructions are also embedded in fonts to tell the operating system how to properly output different character sequences. A simple solution to the placement of combining marks or diacritics is assigning the marks a width of zero and placing the glyph itself to the left or right of the left sidebearing (depending on the direction of the script they are intended to be used with). A mark handled this way will appear over whatever character precedes it, but will not adjust its position relative to the width or height of the base glyph; it may be visually awkward and it may overlap some glyphs. Real stacking is impossible, but can be approximated in limited cases (for example, Thai top-combining vowels and tone marks can just be at different heights to start with). Generally this approach is only effective in monospaced fonts, but may be used as a fallback rendering method when more complex methods fail.

Standardized subsets

Several subsets of Unicode are standardized: Microsoft Windows since Windows NT 4.0 supports WGL-4 with 656 characters, which is considered to support all contemporary European languages using the Latin, Greek, or Cyrillic script. Other standardized subsets of Unicode include the Multilingual European Subsets:[62]

MES-1 (Latin scripts only, 335 characters), MES-2 (Latin, Greek and Cyrillic 1062 characters)[63] and MES-3A & MES-3B (two larger subsets, not shown here). Note that MES-2 includes every character in MES-1 and WGL-4.

| Row | Cells | Range(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 00 | 20–7E | Basic Latin (00–7F) |

| A0–FF | Latin-1 Supplement (80–FF) | |

| 01 | 00–13, 14–15, 16–2B, 2C–2D, 2E–4D, 4E–4F, 50–7E, 7F | Latin Extended-A (00–7F) |

| 8F, 92, B7, DE-EF, FA–FF | Latin Extended-B (80–FF ...) | |

| 02 | 18–1B, 1E–1F | Latin Extended-B (... 00–4F) |

| 59, 7C, 92 | IPA Extensions (50–AF) | |

| BB–BD, C6, C7, C9, D6, D8–DB, DC, DD, DF, EE | Spacing Modifier Letters (B0–FF) | |

| 03 | 74–75, 7A, 7E, 84–8A, 8C, 8E–A1, A3–CE, D7, DA–E1 | Greek (70–FF) |

| 04 | 00–5F, 90–91, 92–C4, C7–C8, CB–CC, D0–EB, EE–F5, F8–F9 | Cyrillic (00–FF) |

| 1E | 02–03, 0A–0B, 1E–1F, 40–41, 56–57, 60–61, 6A–6B, 80–85, 9B, F2–F3 | Latin Extended Additional (00–FF) |

| 1F | 00–15, 18–1D, 20–45, 48–4D, 50–57, 59, 5B, 5D, 5F–7D, 80–B4, B6–C4, C6–D3, D6–DB, DD–EF, F2–F4, F6–FE | Greek Extended (00–FF) |

| 20 | 13–14, 15, 17, 18–19, 1A–1B, 1C–1D, 1E, 20–22, 26, 30, 32–33, 39–3A, 3C, 3E, 44, 4A | General Punctuation (00–6F) |

| 7F, 82 | Superscripts and Subscripts (70–9F) | |

| A3–A4, A7, AC, AF | Currency Symbols (A0–CF) | |

| 21 | 05, 13, 16, 22, 26, 2E | Letterlike Symbols (00–4F) |

| 5B–5E | Number Forms (50–8F) | |

| 90–93, 94–95, A8 | Arrows (90–FF) | |

| 22 | 00, 02, 03, 06, 08–09, 0F, 11–12, 15, 19–1A, 1E–1F, 27–28, 29, 2A, 2B, 48, 59, 60–61, 64–65, 82–83, 95, 97 | Mathematical Operators (00–FF) |

| 23 | 02, 0A, 20–21, 29–2A | Miscellaneous Technical (00–FF) |

| 25 | 00, 02, 0C, 10, 14, 18, 1C, 24, 2C, 34, 3C, 50–6C | Box Drawing (00–7F) |

| 80, 84, 88, 8C, 90–93 | Block Elements (80–9F) | |

| A0–A1, AA–AC, B2, BA, BC, C4, CA–CB, CF, D8–D9, E6 | Geometric Shapes (A0–FF) | |

| 26 | 3A–3C, 40, 42, 60, 63, 65–66, 6A, 6B | Miscellaneous Symbols (00–FF) |

| F0 | (01–02) | Private Use Area (00–FF ...) |

| FB | 01–02 | Alphabetic Presentation Forms (00–4F) |

| FF | FD | Specials |

Rendering software which cannot process a Unicode character appropriately often displays it as an open rectangle, or the Unicode "replacement character" (U+FFFD, �), to indicate the position of the unrecognized character. Some systems have made attempts to provide more information about such characters. Apple's Last Resort font will display a substitute glyph indicating the Unicode range of the character, and the SIL International's Unicode Fallback font will display a box showing the hexadecimal scalar value of the character.

Mapping and encodings

Several mechanisms have been specified for storing a series of code points as a series of bytes.

Unicode defines two mapping methods: the Unicode Transformation Format (UTF) encodings, and the Universal Coded Character Set (UCS) encodings. An encoding maps (possibly a subset of) the range of Unicode code points to sequences of values in some fixed-size range, termed code units. All UTF encodings map code points to a unique sequence of bytes.[64] The numbers in the names of the encodings indicate the number of bits per code unit (for UTF encodings) or the number of bytes per code unit (for UCS encodings and UTF-1). UTF-8 and UTF-16 are the most commonly used encodings. UCS-2 is an obsolete subset of UTF-16; UCS-4 and UTF-32 are functionally equivalent.

UTF encodings include:

- UTF-1, a retired predecessor of UTF-8, maximizes compatibility with ISO 2022, no longer part of The Unicode Standard

- UTF-7, a 7-bit encoding sometimes used in e-mail, often considered obsolete (not part of The Unicode Standard, but only documented as an informational RFC, i.e., not on the Internet Standards Track)

- UTF-8, uses one to four bytes for each code point, maximizes compatibility with ASCII

- UTF-EBCDIC, similar to UTF-8 but designed for compatibility with EBCDIC (not part of The Unicode Standard)

- UTF-16, uses one or two 16-bit code units per code point, cannot encode surrogates

- UTF-32, uses one 32-bit code unit per code point

UTF-8 uses one to four bytes per code point and, being compact for Latin scripts and ASCII-compatible, provides the de facto standard encoding for interchange of Unicode text. It is used by FreeBSD and most recent Linux distributions as a direct replacement for legacy encodings in general text handling.

The UCS-2 and UTF-16 encodings specify the Unicode Byte Order Mark (BOM) for use at the beginnings of text files, which may be used for byte ordering detection (or byte endianness detection). The BOM, code point U+FEFF has the important property of unambiguity on byte reorder, regardless of the Unicode encoding used; U+FFFE (the result of byte-swapping U+FEFF) does not equate to a legal character, and U+FEFF in other places, other than the beginning of text, conveys the zero-width non-break space (a character with no appearance and no effect other than preventing the formation of ligatures).

The same character converted to UTF-8 becomes the byte sequence EF BB BF. The Unicode Standard allows that the BOM "can serve as signature for UTF-8 encoded text where the character set is unmarked".[65] Some software developers have adopted it for other encodings, including UTF-8, in an attempt to distinguish UTF-8 from local 8-bit code pages. However RFC 3629, the UTF-8 standard, recommends that byte order marks be forbidden in protocols using UTF-8, but discusses the cases where this may not be possible. In addition, the large restriction on possible patterns in UTF-8 (for instance there cannot be any lone bytes with the high bit set) means that it should be possible to distinguish UTF-8 from other character encodings without relying on the BOM.

In UTF-32 and UCS-4, one 32-bit code unit serves as a fairly direct representation of any character's code point (although the endianness, which varies across different platforms, affects how the code unit manifests as a byte sequence). In the other encodings, each code point may be represented by a variable number of code units. UTF-32 is widely used as an internal representation of text in programs (as opposed to stored or transmitted text), since every Unix operating system that uses the gcc compilers to generate software uses it as the standard "wide character" encoding. Some programming languages, such as Seed7, use UTF-32 as internal representation for strings and characters. Recent versions of the Python programming language (beginning with 2.2) may also be configured to use UTF-32 as the representation for Unicode strings, effectively disseminating such encoding in high-level coded software.

Punycode, another encoding form, enables the encoding of Unicode strings into the limited character set supported by the ASCII-based Domain Name System (DNS). The encoding is used as part of IDNA, which is a system enabling the use of Internationalized Domain Names in all scripts that are supported by Unicode. Earlier and now historical proposals include UTF-5 and UTF-6.

GB18030 is another encoding form for Unicode, from the Standardization Administration of China. It is the official character set of the People's Republic of China (PRC). BOCU-1 and SCSU are Unicode compression schemes. The April Fools' Day RFC of 2005 specified two parody UTF encodings, UTF-9 and UTF-18.

Adoption

Operating systems

Unicode has become the dominant scheme for internal processing and storage of text. Although a great deal of text is still stored in legacy encodings, Unicode is used almost exclusively for building new information processing systems. Early adopters tended to use UCS-2 (the fixed-width two-byte precursor to UTF-16) and later moved to UTF-16 (the variable-width current standard), as this was the least disruptive way to add support for non-BMP characters. The best known such system is Windows NT (and its descendants, Windows 2000, Windows XP, Windows Vista, Windows 7, Windows 8 and Windows 10), which uses UTF-16 as the sole internal character encoding. The Java and .NET bytecode environments, macOS, and KDE also use it for internal representation. Partial support for Unicode can be installed on Windows 9x through the Microsoft Layer for Unicode.

UTF-8 (originally developed for Plan 9)[66] has become the main storage encoding on most Unix-like operating systems (though others are also used by some libraries) because it is a relatively easy replacement for traditional extended ASCII character sets. UTF-8 is also the most common Unicode encoding used in HTML documents on the World Wide Web.

Multilingual text-rendering engines which use Unicode include Uniscribe and DirectWrite for Microsoft Windows, ATSUI and Core Text for macOS, and Pango for GTK+ and the GNOME desktop.

Input methods

Because keyboard layouts cannot have simple key combinations for all characters, several operating systems provide alternative input methods that allow access to the entire repertoire.

ISO/IEC 14755,[67] which standardises methods for entering Unicode characters from their code points, specifies several methods. There is the Basic method, where a beginning sequence is followed by the hexadecimal representation of the code point and the ending sequence. There is also a screen-selection entry method specified, where the characters are listed in a table in a screen, such as with a character map program.

Online tools for finding the code point for a known character include Unicode Lookup[68] by Jonathan Hedley and Shapecatcher[69] by Benjamin Milde. In Unicode Lookup, one enters a search key (e.g. "fractions"), and a list of corresponding characters with their code points is returned. In Shapecatcher, based on Shape context, one draws the character in a box and a list of characters approximating the drawing, with their code points, is returned.

Email

MIME defines two different mechanisms for encoding non-ASCII characters in email, depending on whether the characters are in email headers (such as the "Subject:"), or in the text body of the message; in both cases, the original character set is identified as well as a transfer encoding. For email transmission of Unicode, the UTF-8 character set and the Base64 or the Quoted-printable transfer encoding are recommended, depending on whether much of the message consists of ASCII characters. The details of the two different mechanisms are specified in the MIME standards and generally are hidden from users of email software.

The adoption of Unicode in email has been very slow. Some East Asian text is still encoded in encodings such as ISO-2022, and some devices, such as mobile phones, still cannot correctly handle Unicode data. Support has been improving, however. Many major free mail providers such as Yahoo, Google (Gmail), and Microsoft (Outlook.com) support it.

Web

All W3C recommendations have used Unicode as their document character set since HTML 4.0. Web browsers have supported Unicode, especially UTF-8, for many years. There used to be display problems resulting primarily from font related issues; e.g. v 6 and older of Microsoft Internet Explorer did not render many code points unless explicitly told to use a font that contains them.[70]

Although syntax rules may affect the order in which characters are allowed to appear, XML (including XHTML) documents, by definition,[71] comprise characters from most of the Unicode code points, with the exception of:

- most of the C0 control codes,

- the permanently unassigned code points D800–DFFF,

- FFFE or FFFF.

HTML characters manifest either directly as bytes according to document's encoding, if the encoding supports them, or users may write them as numeric character references based on the character's Unicode code point. For example, the references Δ, Й, ק, م, ๗, あ, 叶, 葉, and 말 (or the same numeric values expressed in hexadecimal, with &#x as the prefix) should display on all browsers as Δ, Й, ק ,م, ๗, あ, 叶, 葉, and 말.

When specifying URIs, for example as URLs in HTTP requests, non-ASCII characters must be percent-encoded.

Fonts

Unicode is not in principle concerned with fonts per se, seeing them as implementation choices.[72] Any given character may have many allographs, from the more common bold, italic and base letterforms to complex decorative styles. A font is "Unicode compliant" if the glyphs in the font can be accessed using code points defined in the Unicode standard.[73] The standard does not specify a minimum number of characters that must be included in the font; some fonts have quite a small repertoire.

Free and retail fonts based on Unicode are widely available, since TrueType and OpenType support Unicode. These font formats map Unicode code points to glyphs, but TrueType font is restricted to 65,535 glyphs.

Thousands of fonts exist on the market, but fewer than a dozen fonts—sometimes described as "pan-Unicode" fonts—attempt to support the majority of Unicode's character repertoire. Instead, Unicode-based fonts typically focus on supporting only basic ASCII and particular scripts or sets of characters or symbols. Several reasons justify this approach: applications and documents rarely need to render characters from more than one or two writing systems; fonts tend to demand resources in computing environments; and operating systems and applications show increasing intelligence in regard to obtaining glyph information from separate font files as needed, i.e., font substitution. Furthermore, designing a consistent set of rendering instructions for tens of thousands of glyphs constitutes a monumental task; such a venture passes the point of diminishing returns for most typefaces.

Newlines

Unicode partially addresses the newline problem that occurs when trying to read a text file on different platforms. Unicode defines a large number of characters that conforming applications should recognize as line terminators.

In terms of the newline, Unicode introduced U+2028 LINE SEPARATOR and U+2029 PARAGRAPH SEPARATOR. This was an attempt to provide a Unicode solution to encoding paragraphs and lines semantically, potentially replacing all of the various platform solutions. In doing so, Unicode does provide a way around the historical platform dependent solutions. Nonetheless, few if any Unicode solutions have adopted these Unicode line and paragraph separators as the sole canonical line ending characters. However, a common approach to solving this issue is through newline normalization. This is achieved with the Cocoa text system in Mac OS X and also with W3C XML and HTML recommendations. In this approach every possible newline character is converted internally to a common newline (which one does not really matter since it is an internal operation just for rendering). In other words, the text system can correctly treat the character as a newline, regardless of the input's actual encoding.

Issues

Philosophical and completeness criticisms

Han unification (the identification of forms in the East Asian languages which one can treat as stylistic variations of the same historical character) has become one of the most controversial aspects of Unicode, despite the presence of a majority of experts from all three regions in the Ideographic Research Group (IRG), which advises the Consortium and ISO on additions to the repertoire and on Han unification.[74]

Unicode has been criticized for failing to separately encode older and alternative forms of kanji which, critics argue, complicates the processing of ancient Japanese and uncommon Japanese names. This is often due to the fact that Unicode encodes characters rather than glyphs (the visual representations of the basic character that often vary from one language to another). Unification of glyphs leads to the perception that the languages themselves, not just the basic character representation, are being merged.[75] There have been several attempts to create alternative encodings that preserve the stylistic differences between Chinese, Japanese, and Korean characters in opposition to Unicode's policy of Han unification. An example of one is TRON (although it is not widely adopted in Japan, there are some users who need to handle historical Japanese text and favor it).

Although the repertoire of fewer than 21,000 Han characters in the earliest version of Unicode was largely limited to characters in common modern usage, Unicode now includes more than 92,000 Han characters, and work is continuing to add thousands more historic and dialectal characters used in China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

Modern font technology provides a means to address the practical issue of needing to depict a unified Han character in terms of a collection of alternative glyph representations, in the form of Unicode variation sequences. For example, the Advanced Typographic tables of OpenType permit one of a number of alternative glyph representations to be selected when performing the character to glyph mapping process. In this case, information can be provided within plain text to designate which alternate character form to select.

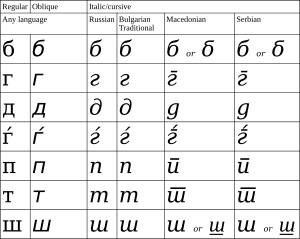

If the difference in the appropriate glyphs for two characters in the same script differ only in the italic, Unicode has generally unified them, as can be seen in the comparison between Russian (labeled standard) and Serbian characters at right, meaning that the differences are displayed through smart font technology or manually changing fonts.

Mapping to legacy character sets

Unicode was designed to provide code-point-by-code-point round-trip format conversion to and from any preexisting character encodings, so that text files in older character sets can be converted to Unicode and then back and get back the same file, without employing context-dependent interpretation. That has meant that inconsistent legacy architectures, such as combining diacritics and precomposed characters, both exist in Unicode, giving more than one method of representing some text. This is most pronounced in the three different encoding forms for Korean Hangul. Since version 3.0, any precomposed characters that can be represented by a combining sequence of already existing characters can no longer be added to the standard in order to preserve interoperability between software using different versions of Unicode.

Injective mappings must be provided between characters in existing legacy character sets and characters in Unicode to facilitate conversion to Unicode and allow interoperability with legacy software. Lack of consistency in various mappings between earlier Japanese encodings such as Shift-JIS or EUC-JP and Unicode led to round-trip format conversion mismatches, particularly the mapping of the character JIS X 0208 '~' (1-33, WAVE DASH), heavily used in legacy database data, to either U+FF5E ~ FULLWIDTH TILDE (in Microsoft Windows) or U+301C 〜 WAVE DASH (other vendors).[76]

Some Japanese computer programmers objected to Unicode because it requires them to separate the use of U+005C \ REVERSE SOLIDUS (backslash) and U+00A5 ¥ YEN SIGN, which was mapped to 0x5C in JIS X 0201, and a lot of legacy code exists with this usage.[77] (This encoding also replaces tilde '~' 0x7E with macron '¯', now 0xAF.) The separation of these characters exists in ISO 8859-1, from long before Unicode.

Indic scripts

Indic scripts such as Tamil and Devanagari are each allocated only 128 code points, matching the ISCII standard. The correct rendering of Unicode Indic text requires transforming the stored logical order characters into visual order and the forming of ligatures (aka conjuncts) out of components. Some local scholars argued in favor of assignments of Unicode code points to these ligatures, going against the practice for other writing systems, though Unicode contains some Arabic and other ligatures for backward compatibility purposes only.[78][79][80] Encoding of any new ligatures in Unicode will not happen, in part because the set of ligatures is font-dependent, and Unicode is an encoding independent of font variations. The same kind of issue arose for the Tibetan script in 2003 when the Standardization Administration of China proposed encoding 956 precomposed Tibetan syllables,[81] but these were rejected for encoding by the relevant ISO committee (ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2).[82]

Thai alphabet support has been criticized for its ordering of Thai characters. The vowels เ, แ, โ, ใ, ไ that are written to the left of the preceding consonant are in visual order instead of phonetic order, unlike the Unicode representations of other Indic scripts. This complication is due to Unicode inheriting the Thai Industrial Standard 620, which worked in the same way, and was the way in which Thai had always been written on keyboards. This ordering problem complicates the Unicode collation process slightly, requiring table lookups to reorder Thai characters for collation.[75] Even if Unicode had adopted encoding according to spoken order, it would still be problematic to collate words in dictionary order. E.g., the word แสดง [sa dɛːŋ] "perform" starts with a consonant cluster "สด" (with an inherent vowel for the consonant "ส"), the vowel แ-, in spoken order would come after the ด, but in a dictionary, the word is collated as it is written, with the vowel following the ส.

Combining characters

Characters with diacritical marks can generally be represented either as a single precomposed character or as a decomposed sequence of a base letter plus one or more non-spacing marks. For example, ḗ (precomposed e with macron and acute above) and ḗ (e followed by the combining macron above and combining acute above) should be rendered identically, both appearing as an e with a macron and acute accent, but in practice, their appearance may vary depending upon what rendering engine and fonts are being used to display the characters. Similarly, underdots, as needed in the romanization of Indic, will often be placed incorrectly.. Unicode characters that map to precomposed glyphs can be used in many cases, thus avoiding the problem, but where no precomposed character has been encoded the problem can often be solved by using a specialist Unicode font such as Charis SIL that uses Graphite, OpenType, or AAT technologies for advanced rendering features.

Anomalies

The Unicode standard has imposed rules intended to guarantee stability.[83] Depending on the strictness of a rule, a change can be prohibited or allowed. For example, a "name" given to a code point cannot and will not change. But a "script" property is more flexible, by Unicode's own rules. In version 2.0, Unicode changed many code point "names" from version 1. At the same moment, Unicode stated that from then on, an assigned name to a code point will never change anymore. This implies that when mistakes are published, these mistakes cannot be corrected, even if they are trivial (as happened in one instance with the spelling BRAKCET for BRACKET in a character name). In 2006 a list of anomalies in character names was first published, and, as of April 2017, there were 94 characters with identified issues,[84] for example:

- U+2118 ℘ SCRIPT CAPITAL P: This is a small letter. The capital is U+1D4AB 𝒫 MATHEMATICAL SCRIPT CAPITAL P[85]

- U+034F ͏ COMBINING GRAPHEME JOINER: Does not join graphemes.[84]

- U+A015 ꀕ YI SYLLABLE WU: This is not a Yi syllable, but a Yi iteration mark.

- U+FE18 ︘ PRESENTATION FORM FOR VERTICAL RIGHT WHITE LENTICULAR BRAKCET: bracket is spelled incorrectly.[86]

Spelling errors are resolved by using Unicode alias names and abbreviations.

See also

- Comparison of Unicode encodings

- Cultural, political, and religious symbols in Unicode

- International Components for Unicode (ICU), now as ICU-TC a part of Unicode

- List of binary codes

- List of Unicode characters

- List of XML and HTML character entity references

- Open-source Unicode typefaces

- Standards related to Unicode

- Unicode symbols

- Universal Coded Character Set

- Lotus Multi-Byte Character Set (LMBCS), a parallel development with similar intentions

Notes

- The Unicode Consortium uses the ambiguous term byte; The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) use the more specific term octet in current documents related to Unicode.

References

- "The Unicode Standard: A Technical Introduction". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Usage Survey of Character Encodings broken down by Ranking". w3techs.com. Retrieved 2020-06-09.

- "Conformance" (PDF). The Unicode Standard. March 2020. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- "UAX #29: Unicode Text Segmentation §3 Grapheme Cluster Boundaries". unicode.org. 2020-02-19. Retrieved 2020-06-27.

- "Unicode – a brief introduction (advanced) • JavaScript for impatient programmers". exploringjs.com. Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- "Introduction to Unicode". mathias.gaunard.com. Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- "Strings and Characters — The Swift Programming Language (Swift 5.2)". docs.swift.org. Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- "Breaking Our Latin-1 Assumptions - In Pursuit of Laziness". manishearth.github.io. Retrieved 2020-06-14.

Unicode didn’t want to deal with adding new flags each time a new country or territory pops up. Nor did they want to get into the tricky business of determining what a country is, for example when dealing with disputed territories. [..] On some Chinese systems, for example, the flag for Taiwan (🇹🇼) may not render.

- "Let's Stop Ascribing Meaning to Code Points - In Pursuit of Laziness". manishearth.github.io. Retrieved 2020-06-14.

Folks start implying that code points mean something, and that O(1) indexing or slicing at code point boundaries is a useful operation.

- Becker, Joseph D. (1998-09-10) [1988-08-29]. "Unicode 88" (PDF). unicode.org (10th anniversary reprint ed.). Unicode Consortium. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-25. Retrieved 2016-10-25.

In 1978, the initial proposal for a set of "Universal Signs" was made by Bob Belleville at Xerox PARC. Many persons contributed ideas to the development of a new encoding design. Beginning in 1980, these efforts evolved into the Xerox Character Code Standard (XCCS) by the present author, a multilingual encoding which has been maintained by Xerox as an internal corporate standard since 1982, through the efforts of Ed Smura, Ron Pellar, and others.

Unicode arose as the result of eight years of working experience with XCCS. Its fundamental differences from XCCS were proposed by Peter Fenwick and Dave Opstad (pure 16-bit codes), and by Lee Collins (ideographic character unification). Unicode retains the many features of XCCS whose utility have been proved over the years in an international line of communication multilingual system products. - "Summary Narrative". Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- History of Unicode Release and Publication Dates on unicode.org. Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- Searle, Stephen J. "Unicode Revisited". Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- "The Unicode Consortium Members". Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- "Character Code Charts". Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- "Unicode FAQ". Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- "Roadmap to the BMP". Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- "About The Script Encoding Initiative". The Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- "Unicode 6.1 Paperback Available". announcements_at_unicode.org. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- "Unicode 14.0 Delayed for 6 Months". Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- "Enumerated Versions of The Unicode Standard". Retrieved 2016-06-21.

- "Unicode Data 1.0.0". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Data 1.0.1". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Data 1995". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Data-2.0.14". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Data-2.1.2". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Data-3.0.0". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Data-3.1.0". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Data-3.2.0". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Data-4.0.0". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Data-4.1.0". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Data 5.0.0". Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- "Unicode Data 5.1.0". Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- "Unicode Data 5.2.0". Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- "Unicode Data 6.0.0". Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- "Unicode Data 6.1.0". Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- "Unicode Data 6.2.0". Retrieved 2012-09-26.

- "Unicode Data 6.3.0". Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- "Unicode Data 7.0.0". Retrieved 2014-06-15.

- "Unicode 8.0.0". Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- "Unicode Data 8.0.0". Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- "Unicode 9.0.0". Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2016-06-21.

- "Unicode Data 9.0.0". Retrieved 2016-06-21.

- Lobao, Martim (2016-06-07). "These Are The Two Emoji That Weren't Approved For Unicode 9 But Which Google Added To Android Anyway". Android Police. Retrieved 2016-09-04.

- "Unicode 10.0.0". Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2017-06-20.

- "The Unicode Standard, Version 11.0.0 Appendix C" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- "Announcing The Unicode Standard, Version 11.0". blog.unicode.org. Retrieved 2018-06-06.

- "The Unicode Standard, Version 12.0.0 Appendix C" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- "Announcing The Unicode Standard, Version 12.0". blog.unicode.org. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- "Unicode Version 12.1 released in support of the Reiwa Era". blog.unicode.org. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- "The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0– Core Specification Appendix C" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- "Announcing The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0". blog.unicode.org. Retrieved 2020-03-11.

- "Glossary of Unicode Terms". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "3.4 Characters and Encoding". The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0 (PDF). 2019. p. 19.

- "2.4 Code Points and Characters". The Unicode Standard Version 12.0 – Core Specification (PDF). 2019. p. 29.

- "Appendix A: Notational Conventions" (PDF). The Unicode Standard. Unicode Consortium. March 2020. In conformity with the bullet point relating to Unicode in MOS:ALLCAPS, the formal Unicode names are not used in this paragraph.

- "Unicode Character Encoding Stability Policy". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Properties" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- "Unicode Character Encoding Model". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Named Sequences". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Unicode Name Aliases". Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- CWA 13873:2000 – Multilingual European Subsets in ISO/IEC 10646-1 CEN Workshop Agreement 13873

- Multilingual European Character Set 2 (MES-2) Rationale, Markus Kuhn, 1998

- "UTF-8, UTF-16, UTF-32 & BOM". Unicode.org FAQ. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- The Unicode Standard, Version 6.2. The Unicode Consortium. 2013. p. 561. ISBN 978-1-936213-08-5.

- Pike, Rob (2003-04-30). "UTF-8 history".

- "ISO/IEC JTC1/SC 18/WG 9 N" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- Hedley, Jonathan (2009). "Unicode Lookup".

- Milde, Benjamin (2011). "Unicode Character Recognition".

- Wood, Alan. "Setting up Windows Internet Explorer 5, 5.5 and 6 for Multilingual and Unicode Support". Alan Wood. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- "Extensible Markup Language (XML) 1.1 (Second Edition)". Retrieved 2013-11-01.

- Bigelow, Charles; Holmes, Kris (September 1993). "The design of a Unicode font" (PDF). Electronic Publishing. VOL. 6(3), 289–305: 292.

- "Fonts and keyboards". Unicode Consortium. 2017-06-28. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- A Brief History of Character Codes, Steven J. Searle, originally written 1999, last updated 2004

- The secret life of Unicode: A peek at Unicode's soft underbelly, Suzanne Topping, 1 May 2001 (Internet Archive)

- AFII contribution about WAVE DASH, "An Unicode vendor-specific character table for japanese". web.archive.org. 2011-04-22. Archived from the original on 2011-04-22.

- ISO 646-* Problem, Section 4.4.3.5 of Introduction to I18n, Tomohiro KUBOTA, 2001

- "Arabic Presentation Forms-A" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- "Arabic Presentation Forms-B" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- "Alphabetic Presentation Forms" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- China (2002-12-02). "Proposal on Tibetan BrdaRten Characters Encoding for ISO/IEC 10646 in BMP" (PDF).

- V. S. Umamaheswaran (2003-11-07). "Resolutions of WG 2 meeting 44" (PDF). Resolution M44.20.

- Unicode stability policy

- "Unicode Technical Note #27: Known Anomalies in Unicode Character Names". unicode.org. 2017-04-10.

- Unicode chart: "actually this has the form of a lowercase calligraphic p, despite its name"

- "Misspelling of BRACKET in character name is a known defect"

Further reading

- The Unicode Standard, Version 3.0, The Unicode Consortium, Addison-Wesley Longman, Inc., April 2000. ISBN 0-201-61633-5

- The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0, The Unicode Consortium, Addison-Wesley Professional, 27 August 2003. ISBN 0-321-18578-1

- The Unicode Standard, Version 5.0, Fifth Edition, The Unicode Consortium, Addison-Wesley Professional, 27 October 2006. ISBN 0-321-48091-0

- Julie D. Allen. The Unicode Standard, Version 6.0, The Unicode Consortium, Mountain View, 2011, ISBN 9781936213016, ().

- The Complete Manual of Typography, James Felici, Adobe Press; 1st edition, 2002. ISBN 0-321-12730-7

- Unicode: A Primer, Tony Graham, M&T books, 2000. ISBN 0-7645-4625-2.

- Unicode Demystified: A Practical Programmer's Guide to the Encoding Standard, Richard Gillam, Addison-Wesley Professional; 1st edition, 2002. ISBN 0-201-70052-2

- Unicode Explained, Jukka K. Korpela, O'Reilly; 1st edition, 2006. ISBN 0-596-10121-X

- Yannis Haralambous; Martin Dürst (2019). "Unicode from a Linguistic Point of View". In Haralambous, Yannis (ed.). Proceedings of Graphemics in the 21st Century, Brest 2018. Brest: Fluxus Editions. pp. 167–183. ISBN 978-2-9570549-1-6.

External links

- Official website

- Unicode at Curlie

- Alan Wood's Unicode Resources – contains lists of word processors with Unicode capability; fonts and characters are grouped by type; characters are presented in lists, not grids.

- Unicode BMP Fallback Font – displays the Unicode value of any character in a document, including in the Private Use Area, rather than the glyph itself.