Tifinagh

Tifinagh (Berber pronunciation: [tifinaɣ]; in Tamazight Latin: Tifinaɣ; in Neo-Tifinagh: ⵜⵉⴼⵉⵏⴰⵖ; in Tuareg Tifinagh: ⵜⵊⵉⵏⵗ or ⵜⵊⵏⵗ) is an abjad script used to write the Tamazight languages.[1]

Neo-Tifinagh, a modern alphabetical derivative of the traditional script, was reintroduced in the 20th century. A slightly-modified version of the traditional script, called Tifinagh IRCAM, is used in a number of Moroccan elementary schools in teaching the Berber language to children as well as a number of publications.[2][3]

| Libyco-Berber | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

Time period | 2nd millennium BC to the present time[4] |

Parent systems | Saharan petroglyphs

|

Child systems | Tifinagh |

Origins

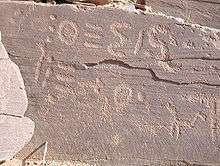

Tifinagh or Libyc was widely used in antiquity by speakers of Libyc languages throughout North Africa and on the Canary Islands. Some authors believe it to be attested from as far back as the 2nd millennium BC, to the present time.[5] The script's origin is considered by most scholars as being of local origin,[6] although a relationship between the Punic alphabet or the Phoenician alphabet has also been suggested.[7] An alternative suggestion, by Helmut Satzinger, is that its origin is to be seen in the Ancient South Arabian script.[8]

The ancient Tifinagh script was a pure abjad; it had no vowels. Gemination was not marked. The writing was usually from the bottom to the top, although right-to-left, and even other orders, were also found. The letters would take different forms when written vertically than when they were written horizontally.[9]

Ancient variants

There are four known variants: Eastern Libyc, Western Libyc, Bu Njem Libyc and Saharan Libyc.

Eastern Libyc or Numidian

The eastern variant covers approximately the north-west of Tunisia as well as eastern Algeria, the western limit of its use is placed at the east of Sétif although inscriptions of the eastern type can exceptionally be in Kabylia, it shows a clear Phoenician influence. It is the best-deciphered variant, due to the discovery of several Numidian bilingual inscriptions in Libyan and Punic (notably at Dougga in Tunisia). Researcher Lionel Galand maintains that there are two versions of Eastern Libyc: one used for monuments, which he called the Dougga script, and one for funerary steles, which is Eastern Libyc proper. The latter contains only 23 letters, which agrees with observations made by historian Fabius Planciades Fulgentius. In the Dougga script, 22 letters out of the 24 were deciphered so far.

Western Libyc or Moorish

The western variant covers Morocco and the western half of Algeria (country populated by the Mauri), as well as the Canary Islands. It is more archaic and shows no Phoenician influence. Its inscriptions are fewer and generally shorter and rougher. The characteristic of this alphabet is that it includes additional signs, that the eastern one is unaware of, whose value could not be given. Some of these characters are identical to the Tuareg letters of the alphabet.

Bu Njem Libyc or Libyan

There are graffiti discovered at Bou Njem, the ancient Gholaia in Libya, on the wall of an old monument which dated from the 3rd century. The writing is horizontal, made up of nine inscriptions. This variant was heavily influenced by Latin to the point of constituting a special alphabet.

Saharan Libyc or Garamantian

This variant was widespread in pre-Saharan and Saharan Libya, territory of the Gaetuli and Garamantes, where it was used by the inhabitants to engrave their messages. It is mostly unknown and badly located.

Tuareg Tifinagh

| Tifinagh | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Tuareg |

Time period | unknown to present |

Parent systems | Libyco-Berber

|

Child systems | Neo-Tifinagh |

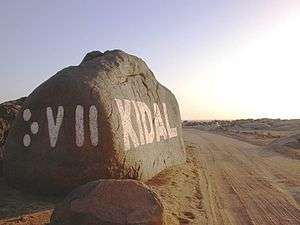

The Libyco-Berber script is used today in the form of Tifinagh to write the Tuareg languages, which belong to the Berber branch of the Afroasiatic family. Early uses of the script have been found on rock art and in various tombs. Among these are the 1500 year old monumental tomb of the Tuareg queen Tin Hinan, where vestiges of a Tifinagh inscription have been found on one of its walls.[10]

According to historians, the Tuareg are "an entirely oral society in which memory and oral communication perform all the functions which reading and writing have in a literate society… The Tifinagh are used primarily for games and puzzles, short graffiti and brief messages."[11]

Occasionally, the script has been used to write other neighbouring languages such as Tagdalt, which is a Northern Songhay language and not a member of the Afroasiatic family.

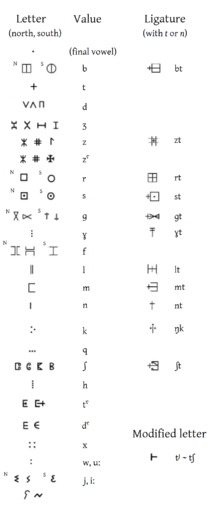

Orthography

Common forms of the letters are illustrated at left, including various ligatures of t and n. Gemination, though phonemic, is not indicated in Tifinagh. The letter t, +, is often combined with a preceding letter to form an orthographic ligature. Most of the letters have more than one common form, including mirror-images of the forms shown here.

When the letters l and n are adjacent to themselves or to each other, the second is offset, either by inclining, lowering, raising, or shortening it. For example, since the letter l is a double line, ||, and n a single line, |, the sequence nn may be written || to differentiate it from l. Similarly, ln is |||, nl |||, ll ||||, nnn |||, etc.

Traditionally, the Tifinagh script does not indicate vowels except word-finally, where a single dot stands for any vowel. In some areas, Arabic vowel diacritics are combined with Tifinagh letters to transcribe vowels, or y, w may be used for long ī and ū.

Neo-Tifinagh

| Neo-Tifinagh | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Standard Moroccan Berber and other Northern Berber languages |

Time period | 1980 to present |

Parent systems | Saharan petroglyphs

|

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Tfng, 120 |

Unicode alias | Tifinagh |

Unicode range | U+2D30–U+2D7F |

Neo-Tifinagh is the modern fully alphabetic script developed from earlier forms of Tifinagh. It is written left to right.

Until recently, virtually no books or websites were published in this alphabet, with activists favouring the Latin (or, more rarely, Arabic) scripts for serious use; however, it is extremely popular for symbolic use, with many books and websites written in a different script featuring logos or title pages using Neo-Tifinagh.

In Morocco, use of Neo-Tifinagh was suppressed until recently. The Moroccan state arrested and imprisoned people using this script during the 1980s and 1990s.[12] In 2003, however, the king took a "neutral" position between the claims of Latin script and Arabic script by adopting Neo-Tifinagh; as a result, books are beginning to be published in this script, and it is taught in some schools. However, many independent Berber-language publications are still published using the Berber Latin alphabet. Outside Morocco, it has no official status.

In Algeria, almost all Berber publications use the Berber Latin Alphabet. The Algerian Black Spring was partly caused by the repression of Berber languages.[13]

In Libya, the government of Muammar Gaddafi consistently banned Tifinagh from being used in public contexts such as store displays and banners.[14]

After the Libyan Civil War, the National Transitional Council has shown an openness towards the Berber languages. The rebel Libya TV, based in Qatar, has included the Berber language and the Tifinagh alphabet in some of its programming.[15]

An IRCAM version of Neo-Tifinagh |

Neo-Tifinagh, Arabic and French at a store in Morocco |

Letters

The following are the letters and a few ligatures of traditional Tifinagh and Neo-Tifinagh:

| Basic Tifinagh (IRCAM)[16] | Extended Tifinagh (IRCAM) | Other Tifinagh letters | Modern Tuareg letters |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unicode

Tifinagh was added to the Unicode Standard in March 2005, with the release of version 4.1.

The Unicode block range for Tifinagh is U+2D30–U+2D7F:

| Tifinagh[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+2D3x | ⴰ | ⴱ | ⴲ | ⴳ | ⴴ | ⴵ | ⴶ | ⴷ | ⴸ | ⴹ | ⴺ | ⴻ | ⴼ | ⴽ | ⴾ | ⴿ |

| U+2D4x | ⵀ | ⵁ | ⵂ | ⵃ | ⵄ | ⵅ | ⵆ | ⵇ | ⵈ | ⵉ | ⵊ | ⵋ | ⵌ | ⵍ | ⵎ | ⵏ |

| U+2D5x | ⵐ | ⵑ | ⵒ | ⵓ | ⵔ | ⵕ | ⵖ | ⵗ | ⵘ | ⵙ | ⵚ | ⵛ | ⵜ | ⵝ | ⵞ | ⵟ |

| U+2D6x | ⵠ | ⵡ | ⵢ | ⵣ | ⵤ | ⵥ | ⵦ | ⵧ | ⵯ | |||||||

| U+2D7x | ⵰ | ⵿ | ||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

References

- To a limited extent: See Interview Archived 2008-05-03 at the Wayback Machine with Karl-G. Prasse and Penchoen (1973:3)

- "Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe" (in French). Ircam.ma. Archived from the original on 2008-04-25. Retrieved 2015-07-14.

- "Institut Royal de la Culture Amazighe". Ircam.ma. Archived from the original on 2008-04-21. Retrieved 2015-07-14.

- Franklin, Natalie R.; Strecker, Matthias (2008-08-05). Rock Art Studies - News of the World Volume 3. Oxbow Books. p. 127. ISBN 9781782975885.

- Franklin, Natalie R.; Strecker, Matthias (2008-08-05). Rock Art Studies - News of the World Volume 3. Oxbow Books. p. 127. ISBN 9781782975885.

- Achab, Karim (2012-03-15). Internal Structure of Verb Meaning: A Study of Verbs in Tamazight (Berber). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 9781443838269.

- Suleiman, Yasir (1996). Language and Identity in the Middle East and North Africa. Psychology Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-7007-0410-1.

- (PDF) https://homepage.univie.ac.at/helmut.satzinger/Texte/Schrift.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Berber". Ancient Scripts. Archived from the original on 2017-08-26. Retrieved 2017-10-09.

- Briggs, L. Cabot (February 1957). "A Review of the Physical Anthropology of the Sahara and Its Prehistoric Implications". Man. 56: 20–23. JSTOR 2793877.

- Millard, Alan Ralph; Piotr, Bienkowski; Mee, C.B. (2005). Writing and Ancient Near East Society: Essays in Honor of Alan Millard. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-567-02691-0.

- "Rapport sur le calvaire de l'écriture en Tifinagh au Maroc". Amazighworld.org. Retrieved 2017-10-09.

- Maddy-Weitzman, Bruce (2011). The Berber Identity Movement and the Challenge to North African States. University of Texas Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-292-72587-4.

- سلطات الامن الليبية تمنع نشر الملصق الرسمي لمهرجان الزي التقليدي بكباو [Libyan security authorities to prevent the publication of the official poster for the festival traditional costume Pkpau] (in Arabic). TAWALT. 2007.

- "Libya TV – News in Berber". Blip.tv. Retrieved 2015-07-14.

- "Polices et Claviers Unicode" (in French). IRCAM. Archived from the original on 2012-03-10. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- "Tuareg alphabet by A. de Motylinski from Grammaire, dialogues et dictionnaire touaregs published by René Basset, Alger, 1908". www.win.tue.nl. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

Bibliography

- Aghali-Zakara, Mohamed (1994). Graphèmes berbères et dilemme de diffusion: Interaction des alphabets latin, ajami et tifinagh. Etudes et Documents Berbères 11, 107-121.

- Aghali-Zakara, Mohamed; and Drouin, Jeanine (1977). Recherches sur les Tifinaghs- Eléments graphiques et sociolinguistiques. Comptes-rendus du Groupe Linguistique des Etudes Chamito-Sémitiques (GLECS).

- Ameur, Meftaha (1994). Diversité des transcriptions : pour une notation usuelle et normalisée de la langue berbère. Etudes et Documents Berbères 11, 25–28.

- Boukous, Ahmed (1997). Situation sociolinguistique de l'Amazigh. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 123, 41–60.

- Chaker, Salem (1994). Pour une notation usuelle à base Tifinagh. Etudes et Documents Berbères 11, 31–42.

- Chaker, Salem (1996). Propositions pour la notation usuelle à base latine du berbère. Etudes et Documents Berbères 14, 239–253.

- Chaker, Salem (1997). La Kabylie: un processus de développement linguistique autonome. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 123, 81–99.

- Durand, O. (1994). Promotion du berbère : problèmes de standardisation et d'orthographe. Expériences européennes. Etudes et Documents Berbères 11, 7–11.

- O'Connor, Michael (1996). The Berber scripts. The World's Writing Systems, ed. by William Bright and Peter Daniels, 112–116. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Penchoen, Thomas G. (1973). Tamazight of the Ayt Ndhir. Los Angeles: Undena Publications.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Savage, Andrew. 2008. Writing Tuareg – the three script options. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 192: 5–14

- Souag, Lameen (2004). "Writing Berber Languages: a quick summary". L. Souag. Archived from the original on 2004-12-05. Retrieved 28 June 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Encyclopaedia of Islam, s.v. Tifinagh.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tifinagh. |

- lbi-project.org, a database of Libyco-Berber inscriptions with images and information

- ancientscripts.com – Berber, a fact file on Tifinagh and a legend of characters

- (in French) ennedi.free.fr, information on Tifinagh

- (in Arabic, French, Tamazight) Ircam.ma, official website of the Royal Institute of the Amazigh Culture

- omniglot.com – Tifinagh

- Unicode character picker for Moroccan Tifinagh

- Tifinagh Font for Windows