Playing card

A playing card is a piece of specially prepared card stock, heavy paper, thin cardboard, plastic-coated paper, cotton-paper blend, or thin plastic that is marked with distinguishing motifs. Often the front (face) and back of each card has a finish to make handling easier. They are most commonly used for playing card games, and are also used in magic tricks, cardistry,[1][2] card throwing,[3] and card houses; cards may also be collected.[4] Some types of cards such as tarot cards are also used for divination. Playing cards are typically palm-sized for convenient handling, and usually are sold together in a set as a deck of cards or pack of cards.

Playing cards are available in a wide variety of styles, as decks may be custom-produced for casinos[5] and magicians[6] (sometimes in the form of trick decks),[7] made as promotional items,[8] or intended as souvenirs,[9][10] artistic works, educational tools,[11][12][13] or branded accessories.[14] Decks of cards or even single cards are also collected as a hobby or for monetary value.[15][16] Different types of card decks can be found in different areas of the world—while the standard 52-card deck is known and used internationally, other types of cards such as Japanese hanafuda and Italian playing cards are well-known in their locales. Cards may also be produced for trading card sets or collectible card games, which can comprise hundreds if not thousands of unique cards.

Playing cards were first invented in China during the Tang dynasty.[17]

History

China

Playing cards may have been invented during the Tang dynasty around the 9th century AD as a result of the usage of woodblock printing technology.[18][19][20][21][22] The first possible reference to card games comes from a 9th-century text known as the Collection of Miscellanea at Duyang, written by Tang dynasty writer Su E. It describes Princess Tongchang, daughter of Emperor Yizong of Tang, playing the "leaf game" in 868 with members of the Wei clan, the family of the princess's husband.[20][23][24] The first known book on the "leaf" game was called the Yezi Gexi and allegedly written by a Tang woman. It received commentary by writers of subsequent dynasties.[25] The Song dynasty (960–1279) scholar Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) asserts that the "leaf" game existed at least since the mid-Tang dynasty and associated its invention with the development of printed sheets as a writing medium.[20][25] However, Ouyang also claims that the "leaves" were pages of a book used in a board game played with dice, and that the rules of the game were lost by 1067.[26]

Other games revolving around alcoholic drinking involved using playing cards of a sort from the Tang dynasty onward. However, these cards did not contain suits or numbers. Instead, they were printed with instructions or forfeits for whomever drew them.[26]

The earliest dated instance of a game involving cards occurred on 17 July 1294 when "Yan Sengzhu and Zheng Pig-Dog were caught playing cards [zhi pai] and that wood blocks for printing them had been impounded, together with nine of the actual cards."[26]

William Henry Wilkinson suggests that the first cards may have been actual paper currency which doubled as both the tools of gaming and the stakes being played for,[19] similar to trading card games. Using paper money was inconvenient and risky so they were substituted by play money known as "money cards". One of the earliest games in which we know the rules is madiao, a trick-taking game, which dates to the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). 15th-century scholar Lu Rong described it is as being played with 38 "money cards" divided into four suits: 9 in coins, 9 in strings of coins (which may have been misinterpreted as sticks from crude drawings), 9 in myriads (of coins or of strings), and 11 in tens of myriads (a myriad is 10,000). The two latter suits had Water Margin characters instead of pips on them[27] with Chinese to mark their rank and suit. The suit of coins is in reverse order with 9 of coins being the lowest going up to 1 of coins as the high card.[28]

Persia and Arabia

Despite the wide variety of patterns, the suits show a uniformity of structure. Every suit contains twelve cards with the top two usually being the court cards of king and vizier and the bottom ten being pip cards. Half the suits use reverse ranking for their pip cards. There are many motifs for the suit pips but some include coins, clubs, jugs, and swords which resemble later Mamluk and Latin suits. Michael Dummett speculated that Mamluk cards may have descended from an earlier deck which consisted of 48 cards divided into four suits each with ten pip cards and two court cards.[29]

Egypt

By the 11th century, playing cards were spreading throughout the Asian continent and later came into Egypt.[30] The oldest surviving cards in the world are four fragments found in the Keir Collection and one in the Benaki Museum. They are dated to the 12th and 13th centuries (late Fatimid, Ayyubid, and early Mamluk periods).[31]

A near complete pack of Mamluk playing cards dating to the 15th century and of similar appearance to the fragments above was discovered by Leo Aryeh Mayer in the Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, in 1939.[32] It is not a complete set and is actually composed of three different packs, probably to replace missing cards.[33] The Topkapı pack originally contained 52 cards comprising four suits: polo-sticks, coins, swords, and cups. Each suit contained ten pip cards and three court cards, called malik (king), nā'ib malik (viceroy or deputy king), and thānī nā'ib (second or under-deputy). The thānī nā'ib is a non-existent title so it may not have been in the earliest versions; without this rank, the Mamluk suits would structurally be the same as a Ganjifa suit. In fact, the word "Kanjifah" appears in Arabic on the king of swords and is still used in parts of the Middle East to describe modern playing cards. Influence from further east can explain why the Mamluks, most of whom were Central Asian Turkic Kipchaks, called their cups tuman which means myriad in Turkic, Mongolian and Jurchen languages.[34] Wilkinson postulated that the cups may have been derived from inverting the Chinese and Jurchen ideogram for myriad (万).

The Mamluk court cards showed abstract designs or calligraphy not depicting persons possibly due to religious proscription in Sunni Islam, though they did bear the ranks on the cards. Nā'ib would be borrowed into French (nahipi), Italian (naibi), and Spanish (naipes), the latter word still in common usage. Panels on the pip cards in two suits show they had a reverse ranking, a feature found in madiao, ganjifa, and old European card games like ombre, tarot, and maw.[35]

A fragment of two uncut sheets of Moorish-styled cards of a similar but plainer style was found in Spain and dated to the early 15th century.[36]

Export of these cards (from Cairo, Alexandria, and Damascus), ceased after the fall of the Mamluks in the 16th century.[37] The rules to play these games are lost but they are believed to be plain trick games without trumps.[38]

Spread across Europe and early design changes

The earliest record of playing cards in Europe is believed by some researchers to be a ban on card games in the city of Berne in 1367,[39][40] although this source is questionable.[41][42] Generally accepted as the first is a Florentine ban dating to 1377.[43][44][45] Also appearing in 1377 was the treatise by John of Rheinfelden, in which he describes playing cards and their moral meaning.[46] From this year onwards more and more records (usually bans) of playing cards occur.[47][48]

Among the early patterns of playing card were those probably derived from the Mamluk suits of cups, coins, swords, and polo-sticks, which are still used in traditional Latin decks.[49] As polo was an obscure sport to Europeans then, the polo-sticks became batons or cudgels.[50] Their presence is attested in Catalonia in 1371, 1377 in Switzerland, and 1380 in many locations including Florence and Paris.[51][52][53] Wide use of playing cards in Europe can, with some certainty, be traced from 1377 onward.[54]

In the account books of Johanna, Duchess of Brabant and Wenceslaus I, Duke of Luxembourg, an entry dated May 14, 1379, by receiver general of Brabant Renier Hollander reads: "Given to Monsieur and Madame four peters and two florins, worth eight and a half sheep, for the purchase of packs of cards".[55] In his book of accounts for 1392 or 1393, Charles or Charbot Poupart, treasurer of the household of Charles VI of France, records payment for the painting of three sets of cards.[56]

From about 1418 to 1450[57] professional card makers in Ulm, Nuremberg, and Augsburg created printed decks. Playing cards even competed with devotional images as the most common uses for woodcuts in this period. Most early woodcuts of all types were coloured after printing, either by hand or, from about 1450 onwards, stencils. These 15th-century playing cards were probably painted. The Flemish Hunting Deck, held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is the oldest complete set of ordinary playing cards made in Europe from the 15th century.[58]

As cards spread from Italy to Germanic countries, the Latin suits were replaced with the suits of leaves (or shields), hearts (or roses), bells, and acorns, and a combination of Latin and Germanic suit pictures and names resulted in the French suits of trèfles (clovers), carreaux (tiles), cœurs (hearts), and piques (pikes) around 1480. The trèfle (clover) was probably derived from the acorn and the pique (pike) from the leaf of the German suits. The names pique and spade, however, may have derived from the sword (spade) of the Italian suits.[59] In England, the French suits were eventually used, although the earliest packs circulating may have had Latin suits.[60] This may account for why the English called the clovers "clubs" and the pikes "spades".

In the late 14th century, Europeans changed the Mamluk court cards to represent European royalty and attendants. In a description from 1377, the earliest courts were originally a seated "king", an upper marshal that held his suit symbol up, and a lower marshal that held it down.[61][62] The latter two correspond with the ober and unter cards found in German and Swiss playing cards. The Italians and Iberians replaced the Ober/Unter system with the "Knight" and "Fante" or "Sota" before 1390, perhaps to make the cards more visually distinguishable. In England, the lowest court card was called the "knave" which originally meant male child (compare German Knabe), so in this context the character could represent the "prince", son to the king and queen; the meaning servant developed later.[63][64] Queens appeared sporadically in packs as early as 1377, especially in Germany. Although the Germans abandoned the queen before the 1500s, the French permanently picked it up and placed it under the king. Packs of 56 cards containing in each suit a king, queen, knight, and knave (as in tarot) were once common in the 15th century.

In 1628, the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards was incorporated under a royal charter by Charles I; the Company received livery status from the Court of Aldermen of the City of London in 1792. The Company still exists today, having expanded its member ranks to include "card makers... card collectors, dealers, bridge players, [and] magicians".[65]

During the mid 16th century, Portuguese traders introduced playing cards to Japan. The first indigenous Japanese deck was the Tenshō karuta named after the Tenshō period.[66]

Later design changes

Packs with corner and edge indices (i.e. the value of the card printed at the corner(s) of the card) enabled players to hold their cards close together in a fan with one hand (instead of the two hands previously used). The first such pack known with Latin suits was printed by Infirerra and dated 1693,[67] but this feature was commonly used only from the end of the 18th century. The first American-manufactured (French) deck with this innovation was the Saladee's Patent, printed by Samuel Hart in 1864. In 1870, he and his cousins at Lawrence & Cohen followed up with the Squeezers, the first cards with indices that had a large diffusion.[4]

This was followed by the innovation of reversible court cards. This invention is attributed to a French card maker of Agen in 1745. But the French government, which controlled the design of playing cards, prohibited the printing of cards with this innovation. In central Europe (Trappola cards) and Italy (Tarocco Bolognese) the innovation was adopted during the second half of the 18th century. In Great Britain, the pack with reversible court cards was patented in 1799 by Edmund Ludlow and Ann Wilcox. The French pack with this design was printed around 1802 by Thomas Wheeler.[68]

Sharp corners wear out more quickly, and could possibly reveal the card's value, so they were replaced with rounded corners. Before the mid-19th century, British, American, and French players preferred blank backs. The need to hide wear and tear and to discourage writing on the back led cards to have designs, pictures, photos, or advertising on the reverse.[69][70]

The United States introduced the joker into the deck. It was devised for the game of euchre, which spread from Europe to America beginning shortly after the American Revolutionary War. In euchre, the highest trump card is the Jack of the trump suit, called the right bower (from the German Bauer); the second-highest trump, the left bower, is the jack of the suit of the same color as trumps. The joker was invented c. 1860 as a third trump, the imperial or best bower, which ranked higher than the other two bowers.[71] The name of the card is believed to derive from juker, a variant name for euchre.[72][73] The earliest reference to a joker functioning as a wild card dates to 1875 with a variation of poker.[74]

Research

Columbia University's Rare Book and Manuscript Library holds the Albert Field Collection of Playing Cards, an archive of over 6,000 individual decks from over 50 countries and dating back to the 1550s.[12] In 2018 the university digitized over 100 of its decks.[75]

Since 2017, Vanderbilt University has been home to the 1,000-volume George Clulow and United States Playing Card Co. Gaming Collection, which has been called one of the "most complete and scholarly collections [of books on cards and gaming] that has ever been gathered together".[76]

Modern deck formats

| French | Hearts |

Tiles |

Clovers |

Pikes |

| German | Hearts |

Bells |

Acorns |

Leaves |

| Italian | Cups |

Coins |

Clubs |

Swords |

| Spanish | Cups |

Coins |

Clubs |

Swords |

| Swiss-German | Roses |

Bells |

Acorns |

Shields |

Contemporary playing cards are grouped into three broad categories based on the suits they use: French, Latin, and Germanic. Latin suits are used in the closely related Spanish and Italian formats. The Swiss-German suits are distinct enough to merit their subcategory. Excluding jokers and tarot trumps, the French 52-card deck preserves the number of cards in the original Mamluk deck, while Latin and Germanic decks average fewer. Latin decks usually drop the higher-valued pip cards, while Germanic decks drop the lower-valued ones.

Within suits, there are regional or national variations called "standard patterns." Because these patterns are in the public domain, this allows multiple card manufacturers to recreate them.[77] Pattern differences are most easily found in the face cards but the number of cards per deck, the use of numeric indices, or even minor shape and arrangement differences of the pips can be used to distinguish them. Some patterns have been around for hundreds of years. Jokers are not part of any pattern as they are a relatively recent invention and lack any standardized appearance so each publisher usually puts its own trademarked illustration into their decks. The wide variation of jokers has turned them into collectible items. Any card that bore the stamp duty like the ace of spades in England, the ace of clubs in France or the ace of coins in Italy are also collectible as that is where the manufacturer's logo is usually placed.

Usually the cards have their indices printed in the upper left and lower right corners, assuming they will be held in the left hand of a right-handed person. This design is often uncomfortable for left-handed people who may prefer to hold their cards in the right hand. To mitigate this issue non-biased designs exist, that have indices in all four corners of the card.[78][79]

French-suited decks

French decks come in a variety of patterns and deck sizes. The 52-card deck is the most popular deck and includes 13 ranks of each suit with reversible "court" or face cards. Each suit includes an ace, depicting a single symbol of its suit, a king, queen, and jack, each depicted with a symbol of their suit; and ranks two through ten, with each card depicting that number of pips of its suit. As well as these 52 cards, commercial packs often include between one and six jokers, most often two.

Decks with fewer than 52 cards are known as stripped decks. The piquet pack has all values from 2 through 6 in each suit removed for a total of 32 cards. It is popular in France, the Low Countries, Central Europe and Russia and is used to play piquet, belote, bezique and skat. It is also used in the Sri Lankan, whist-based game known as omi. Forty-card French suited packs are common in northwest Italy; these remove the 8s through 10s like Latin suited decks. 24 card decks, removing 2s through 8s are also sold in Austria and Bavaria to play schnapsen.

A pinochle deck consists of two copies of a 24 card schnapsen deck, thus 48 cards.

The 78 card tarot nouveau adds the knight card between queens and jacks along with 21 numbered trumps and the unnumbered Fool.

Manufacturing

Today the process of making playing cards is highly automated. Large sheets of paper are glued together to create a sheet of pasteboard; the glue may be black or dyed another dark color to increase the card stock's opacity. In the industry, this black compound is sometimes known as "gick". Some card manufacturers may purchase pasteboard from various suppliers; large companies such as USPCC create their own proprietary pasteboard. After the desired imagery is etched into printing plates, the art is printed onto each side of the pasteboard sheet, which is coated with a textured or smooth finish, sometimes called a varnish or print coating. These coatings can be water- or solvent-based, and different textures and visual effects can be achieved by adding certain dyes or foils, or using multiple varnish processes.[80]

The pasteboard is then split into individual uncut sheets, which are cut into single cards and sorted into decks.[81] The corners are then rounded, after which the decks are packaged, commonly in tuck boxes wrapped in cellophane. The tuck box may have a seal applied.[82][83]

Card manufacturers must pay special attention to the registration of the cards, as non-symmetrical cards can be used to cheat.[84][5]

Design and use

Casinos

Gambling corporations commonly have playing cards made specifically for their casinos. As casinos go through large numbers of decks each day, they may sometimes resell used cards that were "on the [casino] floor". The cards sold to the public are altered, either by cutting the deck's corners or by punching a hole in the deck[5] to prevent these cards from being used in the casino to cheat.

Collecting

Because of the long history and wide variety in designs, playing cards are also collector's items.[85] According to Guinness World Records, the largest playing card collection comprises 11,087 decks and is owned by Liu Fuchang of China.[86] Individual playing cards are also collected, such as the world record collection of 8,520 different Jokers belonging to Tony De Santis of Italy.[87]

Custom designs and artwork

Custom decks may be produced for myriad purposes. Across the world, both individuals and large companies such as United States Playing Card Company (USPCC) design and release many different styles of decks,[88] including commemorative decks[89] and souvenir decks.[10][90] Bold and colorful designs tend to be used for cardistry decks,[1][91][92] while more generally, playing cards (as well as tarot cards) may focus on artistic value.[89][93][94][95] Custom deck production is commonly funded on platforms such as Kickstarter,[96][97][98] with companies as large as USPCC[88] and Cartamundi[99] offering card printing services to the public.

In 1976, the JPL Gallery in London commissioned a card deck from a variety of contemporary British artists including Maggie Hambling, Patrick Heron, David Hockney, Howard Hodgkin, John Hoyland, and Allen Jones called "The Deck of Cards".[100] Forty years later in 2016, the British Council commissioned a similar deck called "Taash ke Patte" featuring Indian artists such as Bhuri Bai, Shilpa Gupta, Krishen Khanna, Ram Rahman, Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, Arpita Singh, and Thukral & Tagra.[100][101][102]

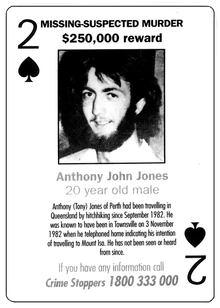

Cold case cards

Police departments,[103] local governments, state prison systems,[104] and even private organizations[105] across the United States have created decks of cards that feature photos, names, and details of cold case victims or missing persons on each card.[12][106] These decks are sold in prison commissaries, or even to the public,[103] in the hopes that an inmate (or anyone else) might provide a new lead.[107] Cold case card programs have been introduced in over a dozen states, including by Oklahoma's State Bureau of Investigation,[108] Connecticut's Division of Criminal Justice, Delaware's Department of Correction,[109] the Florida Department of Law Enforcement,[110] and Rhode Island's Department of Corrections,[111] among others. Among inmates, they may be called "snitch cards".[112]

Symbols in Unicode

| ♠ ♡ ♢ ♣ ♤ ♥ ♦ ♧ | |

|---|---|

Suit symbols | |

| In Unicode | U+2660 ♠ BLACK SPADE SUIT U+2661 ♡ WHITE HEART SUIT |

The Unicode standard for text encoding on computers defines 8 characters for card suits in the Miscellaneous Symbols block, at U+2660–2667. Unicode 7.0 added a unified pack for French-suited tarot nouveau's trump cards and the 52 cards of the modern French pack, with 4 knights, together with a character for "Playing Card Back" and black, red, and white jokers in the block U+1F0A0–1F0FF.[113]

The Unicode names for each group of four glyphs are 'black' and 'white' but might have been more accurately described as 'solid' and 'outline' since the colour actually used at display or printing time is an application choice.

See also

- Types of decks

- Uses

- Geographic origin

- Chinese playing cards

- French playing cards

- Ganjifa

- German playing cards

- Hanafuda

- Italian playing cards

- Karuta

- Spanish playing cards

- Swiss playing cards

- Tujeon

- Terminology

- Glossary of card game terms

- List of playing card nicknames

- Specific decks

- Archaeology awareness playing cards

- Most-wanted Iraqi playing cards

- Politicards

- Trading card

- Zener cards (parapsychology)

- Sources for further information

- Cary Collection of Playing Cards

- International Playing-Card Society

- Musée Français de la Carte à Jouer

- Museum of Fournier de Naipes

- Playing card manufacturers

Further reading

- Maltese playing cards. Bonello, Giovanni (January 2005). Michael Cooper (ed.). "The Playing-card" (PDF). Journal of the International Playing-Card Society. 32 (3): 191–197. ISSN 0305-2133. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2005.

- Griffiths, Antony. Prints and Printmaking British Museum Press (in UK),2nd edn, 1996 ISBN 0-7141-2608-X

- Hind, Arthur M. An Introduction to a History of Woodcut. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in USA), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963 ISBN 0-486-20952-0

- Roman du Roy Meliadus de Leonnoys (British Library, Add MS 12228, fol. 313v), c. 1352

- Singer, Samuel Weller (1816), Researches into the History of Playing Cards, R. Triphook

References

Citations

- Pang, Kevin (April 21, 2015). "72 Hours Inside the Eye-Popping World of Cardistry". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Cepeda, Esther (July 26, 2019). "Cardistry transforms deck of cards into performance art". Post Independent. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Klimek, Chris (November 30, 2018). "Ricky Jay Remembered, From The Wings: An Assistant's Thoughts On The Late Magician". NPR. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

The second act climaxed with him throwing cards into watermelon, first the squishy interior, then the "pachydermatic outer melon layer."

- Hochman, Gene; Dawson, Tom; Dawson, Judy (2000). The Hochman Encyclopedia of American Playing Cards. Stamford, CT: U.S. Games Systems. ISBN 1572812974. OCLC 44732377.

- Kaplan, Michael (June 29, 2016). "How 'Advantage Players' Game the Casinos". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Wong, Alex (April 4, 2019). "How young magicians are learning to cast a spell on a modern audience". National Post. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Mallonee, Laura (November 9, 2018). "The Secret Tools Magicians Use to Fool You". Wired. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Hegel, Theresa (January 10, 2018). "Smart Promotional Items at CES". Advertising Specialty Institute. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Sawyer, Miranda (June 2, 2019). "'The public has a right to art': the radical joy of Keith Haring". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

His art is everywhere. There are Haring T-shirts, Haring shoes, Haring chairs. You can buy Haring baseball hats and badges and baby-carriers and playing cards and stickers and keyrings.

- Wilson, Lexi (December 1, 2018). "A new deck of cards with a Bakersfield twist". Bakersfield Now. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Xinhua (2019-05-17). "Shanghai uses playing cards to promote garbage sorting". China Daily. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Associated Press (2008-10-12). "N.Y card collection includes 6,356 decks". NBC News. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Stack Commerce (January 16, 2018). "These playing cards help you learn about design". Popular Science. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Ramzi, Lilah (February 25, 2019). "All Dressed Up and Nowhere to Go: The Best Looks to Wear at Home". Vogue. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

Tiffany & Co. playing cards, $115

- Seideman, David (January 18, 2019). "Trading Cards Continue To Trounce The S&P 500 As Alternative Investments". Forbes. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Sullivan, Paul (March 23, 2018). "Trading Cards: A Hobby That Became a Multimillion-Dollar Investment". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Who invented playing cards? - Quatr.us". quatr.us. Archived from the original on 2017-04-21.

- Needham 1954, pp. 131–132.

- Wilkinson, W.H. (1895). "Chinese Origin of Playing Cards" (PDF). American Anthropologist. VIII (1): 61–78. doi:10.1525/aa.1895.8.1.02a00070.

- Lo, A. (2009). "The game of leaves: An inquiry into the origin of Chinese playing cards". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 63 (3): 389–406. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00008466.

- Needham 2004, p. 328 "it is also now rather well-established that dominoes and playing-cards were originally Chinese developments from dice."

- Needham 2004, p. 332 "Numbered dice, anciently widespread, were on a related line of development which gave rise to dominoes and playing-cards (+9th-century China)."

- Zhou, Songfang (1997). "On the Story of Late Tang Poet Li He". Journal of the Graduates Sun Yat-sen University. 18 (3): 31–35.

- Needham & Tsien 1985, p. 131.

- Needham 2004, p. 132.

- Parlett, David, "The Chinese "Leaf" Game", March 2015.

- Needham & Tsien 1985, p. 132.

- Money-suited playing cards at The Mahjong Tile Set

- Playing card basics at the International Playing-Card Society website

- Needham & Tsien 1985, p. 307.

- Dummett, Michael (1980). The Game of Tarot. Duckworth. p. 41. ISBN 0-7156-1014-7.

- Mayer, Leo Ary (1939), Le Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, 38, pp. 113–118, retrieved 2008-09-08.

- International Playing Cards Society Journal, 30-3, page 139

- Pollett, Andrea "The Playing-Card", Vol. 31, No 1 pp. 34–41.

- Mamluk cards. Cards.old.no. Retrieved on 2015-05-10.

- Wintle, Simon. Moorish playing cards at The World of Playing Cards. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- The Mamluk Cards. L-pollett.tripod.com. Retrieved on 2015-05-10.

- No trump trick-taking games at pagat.com

- Peter F. Kopp: Die frühesten Spielkarten in der Schweiz. In: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 30 (1973), pp. 130–145, here 130.

- Timothy B. Husband: The World in Play. Luxury Cards 1430–1540. Metropolitan Museum of Art 2016, S. 13.

- Hellmut Rosenfeld: Zu den frühesten Spielkarten in der Schweiz. Eine Entgegnung. In: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 32 (1975), pp. 179–180.

- Early Prohibitions of Playing Cards (Trionfi.com)

- Peter F. Kopp: Die frühesten Spielkarten in der Schweiz. In: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 30 (1973), pp. 130–145, here 130.

- Hellmut Rosenfeld: Zu den frühesten Spielkarten in der Schweiz. Eine Entgegnung. In: Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 32 (1975), pp. 179–180.

- Detlef Hoffmann: Kultur- und Kunstgeschichte der Spielkarte. Marburg: Jonas Verlag 1995, p. 43.

- "Johannes of Rheinfelden, 1377". Trionfi. Retrieved 2015-09-28.

- Wilhelm Ludwig Schreiber: Die ältesten Spielkarten und die auf das Kartenspiel Bezug habenden Urkunden des 14. und 15. Jahrhunderts. Heitz, Straßburg 1937.

- Early Prohibitions of Playing Cards (Trionfi.com)

- Donald Laycock in Skeptical—a Handbook of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal, ed Donald Laycock, David Vernon, Colin Groves, Simon Brown, Imagecraft, Canberra, 1989, ISBN 0-7316-5794-2, p. 67

- Andy's Playing Cards - The Tarot And Other Early Cards - page XVII - the moorish deck. L-pollett.tripod.com. Retrieved on 2015-05-10.

- "Tarot and its history". Trionfi.

- "Tarot and its history". Trionfi.

- J. Brunet i Bellet, Lo joch de naibs, naips o cartas, Barcelona, 1886, quote in the "Diccionari de rims de 1371 : darrerament/per ensajar/de bandejar/los seus guarips/joch de nayps/de nit jugàvem, see also le site trionfi.com

- Banzhaf, Hajo (1994), Il Grande Libro dei Tarocchi (in Italian), Roma: Hermes Edizioni, pp. 16, 192, ISBN 978-88-7938-047-8

- Guiffrey, Jules (1871). "Recherches sur les cartes à jouer et sur leur fabrication en Belgique depuis 1379 jusqu'à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, par Alexandre Pinchar". Bibliothèque de l'École des chartes. 32 (1): 198–199.

- Olmert, Michael (1996). Milton's Teeth and Ovid's Umbrella: Curiouser & Curiouser Adventures in History, p.135. Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 0-684-80164-7.

- "Early Card painters and Printers in Germany, Austria and Flandern (14th and 15th century)". Trionfi.

- "The Cloisters Playing Cards, ca. 1475–80". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- "Early Playing Cards Research". Trionfi. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "The Introduction of Playing-Cards to Europe". jducoeur.org.

- History of Playing-Cards at International Playing-Card Society website

- Wintle, Simon. Early references to Playing Cards at World of Playing Cards.

- Barrington, Daines (1787). Archaeologia, or, Miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity. 8. Society of Antiquaries of London. p. 141.

- "knave, n, 2". Oxford English Dictionary (2 ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 1989.

- "Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards". Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing Cards. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Andy's Playing Cards - Japanese and Korean Cards. L-pollett.tripod.com. Retrieved on 2015-05-10.

- International Playing Cards Society Journal 30-1 page 34

- International Playing Cards Society Journal. XXVII-5 p. 186; and 31-1 p. 22

- Fryxell, David A. (2014-02-07) History Matters: Playing Cards. Family Tree Magazine.

- "Playing cards featuring logo of the FJ Holden". National Museum of Australia.

- Parlett, David (1990), The Oxford Guide to Card Games, Oxford University Press, p. 190, ISBN 978-0-19-214165-1

- US Playing Card Co. – A Brief History of Playing Cards (archive.org mirror)

- Beal, George (1975). Playing cards and their story. New York: Arco Publishing Comoany Inc. p. 58

- Parlett, David (1990), The Oxford Guide to Card Games, Oxford University Press, p. 191, ISBN 978-0-19-214165-1

- "Collections News | Albert Field Playing Cards go online". News from Columbia's Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Columbia University Libraries. September 10, 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Owens, Anne Marie Dear (August 25, 2017). "Vanderbilt now home to extraordinary gaming collection". Vanderbilt University. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- "Standard pattern notes". I-p-c-s.org. Archived from the original on December 11, 2018. Retrieved 2015-05-10.

- "Lefty's "Always right" double deck of playing cards".

- "Sinister Deck: The Left-Handed Card Deck With Famous Lefties".

- "Special Techniques". Cartamundi. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Curcio, Tony (August 7, 2017). "Rollem installs new Slipstream Automatic Card-Cutting System at Napco". Graphic Arts. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

Upon learning that this specialized slitting, collating, and round-cornering machine is used by the world's top playing card manufacturers, and after seeing demonstrations of full press sheets trimmed, cut, collated and round-cornered at speeds up to 2,000 sheets per hour with 100% accuracy, we knew we had found our solution.

- Matthews, Andy (July 27, 2017). "How Playing Cards Are Made". Meeple Mountain. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- US 4779401, Thomas Pedersen, "Arrangement for manufacturing and packaging cards, especially playing cards", published 1988-10-25

- Associated Press (August 15, 2015). "Casino: Cards destroyed before knowing of scheme". Courier Post. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Attina, Andy (April 8, 2010). "Mayfield Heights man displays almost 4,000 playing card decks he has collected in just 10 years". cleveland.com. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- "Largest collection of playing cards". Guinness World Records. November 1, 2007. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- "Largest collection of joker playing cards". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- "Custom Printing - Customized Playing Cards". Bicycle Playing Cards. The United States Playing Card Company. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- "Did you know that the Soviet Union created a Maya playing cards deck back in the 50s?". Yucatan Times. December 7, 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Clark, Natalie (July 9, 2019). "New deck of cards features stories of veteran-run businesses, charities". WLWT5. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Klara, Robert (June 15, 2016). "How One of YouTube's Most Hypnotic Stars Is Building a Brand Around His 'Cardistry'". Adweek. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Thomas, Nicole; Helmen, Jake (February 26, 2019). "Ball State juniors raise awareness with custom playing card company". Ball State Daily News. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Lee, Giacomo (February 6, 2019). "55 leading designers and illustrators have designed the world's most unique deck of cards". Digital Arts. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Walker, Harron (February 20, 2019). "This Artist Is Making the Queerest Deck of Cards Ever". Out Magazine. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Tortorello, Michael (November 2, 2017). "Decks of Cards That Will Wow Your Poker Buddies". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Cherney, Elyssa (April 15, 2019). "Crowdfunding is a popular way to raise money. Just don't count on getting a refund if something goes wrong". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Glatzer, Jason (June 27, 2015). "Peeking On the Future of Poker: What's Going On At Kickstarter". PokerNews. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Blanchard, Kaitlyn (May 14, 2019). "Swinburne alumnus works his magic". Swinburne University of Technology. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Custom Playing Cards for cardistry and magic". Cartamundi. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- "Leading the pack: A card-size survey of modern and contemporary Indian art". Christie's. 19 May 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Chattopadhyay, Pallavi (May 14, 2016). "Check Mate: For the love of playing cards". The Indian Express. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- Lopez, Rachel (June 15, 2017). "Aces! Christie's to auction deck of cards painted by 54 Indian artists". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "Rhode Island Cold Case by Pawtucket Police Department". Rhode Island Cold Case. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Cold Case Cards". Connecticut State Department of Correction. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Masters, Emily (October 29, 2017). "New York cold case playing cards hit 10-year mark". Times Union. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Balchunas, Caroline (October 18, 2017). "Cold case playing cards given to Lowcountry inmates offer hope of solving old crimes". WCIV ABC 4. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Janos, Adam (December 29, 2017). "How Inmates Help Solve Cold-Case Murders While Playing Cards". A&E. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Harmon, Drew (July 22, 2019). "OSBI unit brings cold cases to light". The Edmond Sun. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Gronau, Ian (December 1, 2018). "Panel raises concern about 'cold case' playing cards in prisons". Delaware State News. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "Cold Case Playing Cards". Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Milkovits, Amanda (December 18, 2018). "Betting on a tipped hand, police to release playing cards featuring cold cases". Providence Journal. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- McCracken, Chance (July 5, 2011). "'Snitch cards' use inmates to help solve crimes". KSL.com. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Unicode – Playing Cards Block (PDF), retrieved 2014-11-08

Cited sources

- Needham, Joseph (1954), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 1, Introductory Orientations, Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph (2004) [1962], Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology; Part 1, Physics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-05802-3

- Needham, Joseph; Tsien, Tsuen-hsuin (1985), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08690-6

External links

| Look up playing card in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Playing cards |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Cards, Playing. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Playing card. |

Playing card societies (collectors and researchers)

History of playing cards

- Timeline playing card and tarot history (1370 - 1800)

- Illustrated history of playing cards

- Illustrated short history of playing cards

- History of playing cards

- History of playing cards

- Taxes and Tax Stamps on Playing Cards

- Short history of playing cards

Playing card iconography

- Catalogue of standard playing card patterns used today and in earlier times

- Examples of courts on playing cards

- Standard and fancy playing cards from around the world

Museums, Institutes and Organisations

Playing card collections online