Dominoes

Dominoes is a family of tile-based games played with rectangular "domino" tiles. Each domino is a rectangular tile with a line dividing its face into two square ends. Each end is marked with a number of spots (also called pips, nips, or dobs) or is blank. The backs of the dominoes in a set are indistinguishable, either blank or having some common design. The domino gaming pieces make up a domino set, sometimes called a deck or pack. The traditional Sino-European domino set consists of 28 dominoes, featuring all combinations of spot counts between zero and six. A domino set is a generic gaming device, similar to playing cards or dice, in that a variety of games can be played with a set.

| Genre(s) | Tile-based game |

|---|---|

| Players | 2 to 4 |

| Playing time | less than 15 minutes |

| Skill(s) required | Tactics, strategy |

The earliest mention of dominoes is from Song dynasty China found in the text Former Events in Wulin by Zhou Mi (1232–1298).[1] Modern dominoes first appeared in Italy during the 18th century, but how Chinese dominoes developed into the modern game is unknown. Italian missionaries in China may have brought the game to Europe.[2]

The name "domino" is most likely from the resemblance to a kind of carnival costume worn during the Venetian Carnival, often consisting of a black-hooded robe and a white mask.[3][4] Despite the coinage of the word polyomino as a generalization, there is no connection between the word "domino" and the number 2 in any language.

Construction and composition of domino sets

European-style dominoes are traditionally made of bone or ivory, or a dark hardwood such as ebony, with contrasting black or white pips (inlaid or painted). Alternatively, domino sets have been made from many different natural materials: stone (e.g., marble, granite or soapstone); other woods (e.g., ash, oak, redwood, and cedar); metals (e.g., brass or pewter); ceramic clay, or even frosted glass or crystal. These sets have a more novel look, and the often heavier weight makes them feel more substantial; also, such materials and the resulting products are usually much more expensive than polymer materials.

Modern commercial domino sets are usually made of synthetic materials, such as ABS or polystyrene plastics, or Bakelite and other phenolic resins; many sets approximate the look and feel of ivory while others use colored or even translucent plastics to achieve a more contemporary look. Modern sets also commonly use a different color for the dots of each different end value (one-spots might have black pips while two-spots might be green, three red, etc.) to facilitate finding matching ends. Occasionally, one may find a domino set made of card stock like that for playing cards. Such sets are lightweight, compact, and inexpensive, and like cards are more susceptible to minor disturbances such as a sudden breeze. Sometimes, dominoes have a metal pin (called a spinner or pivot) in the middle.[5]

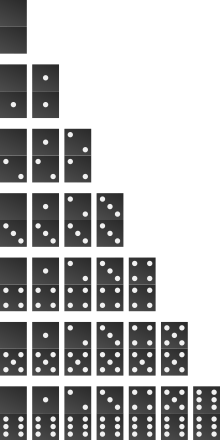

The traditional set of dominoes contains one unique piece for each possible combination of two ends with zero to six spots, and is known as a double-six set because the highest-value piece has six pips on each end (the "double six"). The spots from one to six are generally arranged as they are on six-sided dice, but because blank ends having no spots are used, seven faces are possible, allowing 28 unique pieces in a double-six set.

However, this is a relatively small number especially when playing with more than four people, so many domino sets are "extended" by introducing ends with greater numbers of spots, which increases the number of unique combinations of ends and thus of pieces. Each progressively larger set increases the maximum number of pips on an end by three, so the common extended sets are double-nine (55 tiles), double-12 (91 tiles), double-15 (136 tiles), and double-18 (190 tiles), which is the maximum in practice. Larger sets such as double-21 (253 tiles) could theoretically exist, but they seem to be extremely rare if non-existant, as that would be far more than is normally necessary for most domino games even with eight players. As the set becomes larger, identifying the number of pips on each domino becomes more difficult, so some large domino sets use more readable Arabic numerals instead of pips.[6].

History

The oldest confirmed written mention of dominoes in China comes from the Former Events in Wulin (i.e., the capital Hangzhou) written by the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) author Zhou Mi (1232–1298), who listed pupai (gambling plaques or dominoes), as well as dice as items sold by peddlers during the reign of Emperor Xiaozong of Song (r. 1162–1189).[1] Andrew Lo asserts that Zhou Mi meant dominoes when referring to pupai, since the Ming author Lu Rong (1436–1494) explicitly defined pupai as dominoes (in regard to a story of a suitor who won a maiden's hand by drawing out four winning pupai from a set).[1]

The earliest known manual written about dominoes is the 《宣和牌譜》 (Manual of the Xuanhe Period) written by Qu You (1341–1437),[1] but some Chinese scholars believe this manual is a forgery from a later time.[7]

In the Encyclopedia of a Myriad of Treasures, Zhang Pu (1602–1641) described the game of laying out dominoes as pupai, although the character for pu had changed, yet retained the same pronunciation.[1] Traditional Chinese domino games include Tien Gow, Pai Gow, Che Deng, and others. The 32-piece Chinese domino set, made to represent each possible face of two thrown dice and thus have no blank faces, differs from the 28-piece domino set found in the West during the mid 18th century.[8] Chinese dominoes with blank faces were known during the 17th century.[9]

Many different domino sets have been used for centuries in various parts of the world to play a variety of domino games. Each domino originally represented one of the 21 results of throwing two six-sided dice (2d6). One half of each domino is set with the pips from one die and the other half contains the pips from the second die. Chinese sets also introduce duplicates of some throws and divide the dominoes into two suits: military and civil.[10] Chinese dominoes are also longer than typical European dominoes.

The early 18th century had dominoes making their way to Europe, making their first appearance in Italy. The game changed somewhat in the translation from Chinese to the European culture. European domino sets contain neither suit distinctions nor the duplicates that went with them. Instead, European sets contain seven additional dominoes, with six of these representing the values that result from throwing a single die with the other half of the tile left blank, and the seventh domino representing the blank-blank (0–0) combination.

Tiles and suits

Domino tiles (also known as "bones"), are normally twice as long as they are wide, which makes it easier to re-stack pieces after use. Tiles usually feature a line in the middle to divide them visually into two squares. The value of either side is the number of spots or pips. In the most common variant (double-six), the values range from six pips down to none or blank.[11] The sum of the two values, i.e. the total number of pips, may be referred to as the rank or weight of a tile; a tile may be described as "heavier" than a "lighter" one that has fewer (or no) pips.

Tiles are generally named after their two values. For instance, the following are descriptions of a tile bearing the values two and five:

- Deuce-five

- Five-deuce

- 2-5

- 5-2

A tile that has the same pips-value on each end is called a double, and is typically referred to as double-zero, double-one, and so on[11]. Conversely, a tile bearing different values is called a single.[12]

Every tile which features a given number is a member of the suit of that number. A single tile is a member of two suits: for example, 0-3 belongs both to the suit of threes and the suit of blanks, or 0 suit.

In some versions the doubles can be treated as an additional suit of doubles. In these versions, the double-six belongs both to the suit of sixes and the suit of doubles. However, the dominant approach is that each double belongs to only one suit.[11]

The most common domino sets commercially available are double six (with 28 tiles) and double nine (with 55 tiles). Larger sets exist and are popular for games involving several players or for players looking for long domino games.

The number of tiles in a double-n set obeys the following formula:[13]

The total number of pips in a double-n set is found by:

i.e. the number of tiles multiplied by the maximum pip-count (n)

e.g. a 6-6 set has (7 x 8) / 2 = 56/2 = 28 tiles, the average number of pips per tile is 6 (range is from 0 to 12), giving a total pip count of 6 x 28 = 168

This formula can be simplified a little bit when is made equal to the total number of doubles in the domino set:

Rules

The most popular type of play are layout games, which fall into two main categories, blocking games and scoring games.

- Most domino games are blocking games, i.e. the objective is to empty one's hand while blocking the opponent's. In the end, a score may be determined by counting the pips in the losing players' hands.

- In scoring games, the scoring is different and happens mostly during game play, making it the principal objective.[12]

- A popular version played predominantly in Singapore, referenced as Hector's Rules, allows for playing double tiles on opponents' hands and awards a bonus play of an additional tile immediately after playing a double tile.

- If an opponent lays all their tiles on their turn, the game is a tie.

Blocking game

The most basic domino variant is for two players and requires a double-six set. The 28 tiles are shuffled face down and form the stock or boneyard. Each player draws seven tiles from the stock. Once the players begin drawing tiles, they are typically placed on-edge in front of the players, so each player can see their own tiles, but none can see the value of other players' tiles. Every player can thus see how many tiles remain in the opponent's hands at all times during gameplay.

One player begins by downing (playing the first tile) one of their tiles. This tile starts the line of play, in which values of adjacent pairs of tile ends must match. The players alternately extend the line of play with one tile at one of its two ends; if a player is unable to place a valid tile, they must continue drawing tiles from the stock until they are able to place a tile. The game ends when one player wins by playing their last tile, or when the game is blocked because neither player can play. If that occurs, whoever caused the block receives all of the remaining player points not counting their own.[11]

Scoring game

Players accrue points during game play for certain configurations, moves, or emptying one's hand. Most scoring games use variations of the draw game. If a player does not call "domino" before the tile is laid on the table, and another player says domino after the tile is laid, the first player must pick up an extra domino.

Draw game

In a draw game (blocking or scoring), players are additionally allowed to draw as many tiles as desired from the stock before playing a tile, and they are not allowed to pass before the stock is (nearly) empty.[11] The score of a game is the number of pips in the losing player's hand plus the number of pips in the stock. Most rules prescribe that two tiles need to remain in the stock.[12] The draw game is often referred to as simply "dominoes".[14]

Adaptations of both games can accommodate more than two players, who may play individually or in teams.[11]

Line of play

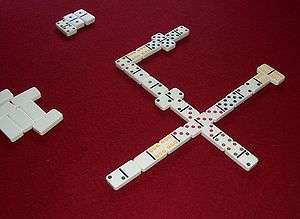

The line of play is the configuration of played tiles on the table. It starts with a single tile and typically grows in two opposite directions when players add matching tiles. In practice, players often play tiles at right angles when the line of play gets too close to the edge of the table.

The rules for the line of play often differ from one variant to another. In many rules, the doubles serve as spinners, i.e., they can be played on all four sides, causing the line of play to branch. Sometimes, the first tile is required to be a double, which serves as the only spinner.[12] In some games such as Chicken Foot, all sides of a spinner must be occupied before anybody is allowed to play elsewhere. Matador has unusual rules for matching. Bendomino uses curved tiles, so one side of the line of play (or both) may be blocked for geometrical reasons.

In Mexican Train and other train games, the game starts with a spinner from which various trains branch off. Most trains are owned by a player and in most situations players are allowed to extend only their own train.

Scoring

In blocking games, scoring happens at the end of the game. After a player has emptied their hand, thereby winning the game for the team, the score consists of the total pip count of the losing team's hands. In some rules, the pip count of the remaining stock is added. If a game is blocked because no player can move, the winner is often determined by adding the pips in players' hands.[12]

In scoring games, each individual can potentially add to the score. For example, in Bergen, players score two points whenever they cause a configuration in which both open ends have the same value and three points if additionally one open end is formed by a double.[15][16] In Muggins, players score by ensuring the total pip count of the open ends is a multiple of a certain number. In variants of Muggins, the line of play may branch due to spinners.

In British public houses and social clubs, a scoring version of "5s-and-3s" is used. The game is normally played in pairs (two against two) and is played as a series of "ends". In each "end", the objective is for players to attach a domino from their hand to one end of those already played so that the sum of the end dominoes is divisible by five or three. One point is scored for each time five or three can be divided into the sum of the two dominoes, i.e. four at one end and five at the other makes nine, which is divisible by three three times, resulting in three points. Double five at one end and five at the other makes 15, which is divisible by three five times (five points) and divisible by five three times (three points) for a total of eight points.

An "end" stops when one of the players is out, i.e., has played all of their dominoes. In the event no player is able to empty their hand, then the player with the lowest domino left in hand is deemed to be out and scores one point. A game consists of any number of ends with points scored in the ends accumulating towards a total. The game ends when one of the pair's total score exceeds a set number of points. A running total score is often kept on a cribbage board. 5s-and-3s is played in a number of competitive leagues in the British Isles.

Variations and game play

For 40 years the game has been played by four people, with the winner being the first player to score 150 points, in multiples of five, by using 28 bones, using mathematical strategic defenses and explosive offense. At times, it has been played with pairs of partners. The double-six set is the preferred deck with the lowest denomination of game pieces, with 28 dominoes.

In many versions of the game, the player with the highest double leads with that double, for example "double-six". If no one has it, the next-highest double is called: "double-five?", then "double-four?", etc. until the highest double in any of the players' hands is played. If no player has an "opening" double, the next heaviest domino in the highest suit is called - "six-five?", "six-four?". In some variants, players take turns picking dominoes from the stock until an opening double is picked and played. In other variants, the hand is reshuffled and each player picks seven dominoes. After the first hand, the winner (or winning team) of the previous hand is allowed to pick first and begins by playing any domino in his or her hand.

Playing the first bone of a hand is sometimes called setting, leading, downing, or posing the first bone. Dominoes aficionados often call this procedure smacking down the bone.[17] After each hand, bones are shuffled and each player draws the number of bones required, normally seven. Play proceeds clockwise. Players, in turn, must play a bone with an end that matches one of the open ends of the layouts.

In some versions of the games, the pips or points on the end, and the section to be played next to it must add up to a given number. For example, in a double-six set, the "sum" would be six, requiring a blank to be played next to a six, an ace (one) next to a five, a deuce (two) next to a four, etc.

The stock of bones left behind, if any, is called the bone yard, and the bones therein are said to be sleeping. In draw games, players take part in the bone selection, typically drawing from the bone yard when they do not have a "match" in their hands.

If a player inadvertently picks up and sees one or more extra dominoes, those dominoes become part of his or her hand.

A player who can play a tile may be allowed to pass anyway. Passing can be signalled by tapping twice on the table or by saying "go" or "pass".

Play continues until one of the players has played all the dominoes in his or her hand, calls "Out!", "I win", or "Domino!" and wins the hand, or until all players are blocked and no legal plays remain. This is sometimes referred to as locked down or sewed up. In a common version of the game, the next player after the block picks up all the dominoes in the bone yard as if trying to find a (nonexistent) match. If all the players are blocked, or locked out, the player with the lowest hand (pip count) wins. In team play, the team with the lowest individual hand wins. In the case of a tie, the first of tied players or the first team in the play rotation wins.

In games where points accrue, the winning player scores a point for each pip on each bone still held by each opponent or the opposing team. If no player went out, the win is determined by the lightest hand, sometimes only the excess points held by opponents.

A game is generally played to 100 points, the tally being kept on paper. In more common games, mainly urban rules, games are played to 150, 200, or 250 points.

In some games, the tally is kept by creating houses, where the beginning of the house (the first 10 points) is a large +, the next 10 points are O, and scoring with a five is a /, and are placed in the four corners of the house. One house is equal to 50 points.

In some versions, if a lock down occurs, the first person to call a lock-down gains the other players bones and adds the amount of the pips to his or her house. If a person who calls rocks after a call of lock-down or domino finds the number of pips a player called is incorrect, those points become his.

Bogus play

When a player plays out of turn or knocks when he could have played and someone calls bogus play, the other person is awarded 50 points. In some places this is known as a compulsory pass.

Card games using domino sets

Apart from the usual blocking and scoring games, also domino games of a very different character are played, such as solitaire or trick-taking games. Most of these are adaptations of card games and were once popular in certain areas to circumvent religious proscriptions against playing cards.[18] A very simple example is a Concentration variant played with a double-six set; two tiles are considered to match if their total pip count is 12.

A popular domino game in Texas is 42. The game is similar to the card game spades. It is played with four players paired into teams. Each player draws seven dominoes, and the dominoes are played into tricks. Each trick counts as one point, and any domino with a multiple of five dots counts toward the total of the hand. These 35 points of "five count" and seven tricks equals 42 points, hence the name.

Competitive play

Dominoes is played at a professional level, similar to poker. Numerous organisations and clubs of amateur domino players exist around the world. Some organizations organize international competitions.

Other uses of dominoes

Besides playing games, another use of dominoes is the domino show, which involves standing them on end in long lines so that when the first tile is toppled, it topples the second, which topples the third, etc., resulting in all of the tiles falling. By analogy, the phenomenon of small events causing similar events leading to eventual catastrophe is called the domino effect.

Arrangements of millions of tiles have been made that have taken many minutes, even hours to fall. For large and elaborate arrangements, special blockages (also known as firebreaks) are employed at regular distances to prevent a premature toppling from undoing more than a section of the dominoes while still being able to be removed without damage.

The phenomenon also has some theoretical relevance (amplifier, digital signal, information processing),[19] and this amounts to the theoretical possibility of building domino computers.[20] Dominoes are also commonly used as components in Rube Goldberg machines.

The Netherlands has hosted an annual domino-toppling exhibition called Domino Day since 1986. The event held on 18 November 2005 knocked over 4 million dominoes by a team from Weijers Domino Productions. On Domino Day 2008 (14 November 2008), the Weijers Domino Productions team attempted to set 10 records:[21]

- Longest domino spiral (200 m)

- Highest domino climb (12 m)

- Smallest domino tile (7 mm)

- Largest domino tile (4.8 m)

- Longest domino wall (16 m)

- Largest domino structure (25,000 tiles)

- Fastest topple of 30 metres of domino tiles (4.21 sec, time by Churandy Martina: 3.81 sec)

- Largest number of domino tiles resting on a single domino (1002 tiles) for more than 1 hour

- Largest rectangular level domino field (1 million tiles)

- A new record of 4,345,027 tiles

This record attempt was held in the WTC Expo hall in Leeuwarden. The artist who toppled the first stone was the Finnish acrobat Salima Peippo.

At one time, Pressman Toys manufactured a product called Domino Rally that contained tiles and mechanical devices for setting up toppling exhibits.

In Berlin on 9 November 2009, giant dominoes were toppled in a 20th-anniversary commemoration of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Former Polish president and Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa set the toppling in motion.

A 2-1 tile is used in the logo of pizza retailer Domino's Pizza.

Dominoes in Unicode

Since April 2008,[22] the character encoding standard Unicode includes characters that represent the double-six domino tiles in various orientations. All combinations of blank through six pips on the left or right provides 49 glyphs, the same combinations vertically for another 49, and also a horizontal and a vertical "back" for a total of 100 glyphs. In this arrangement, both orientations are present: horizontally both tiles [1|6] and [6|1] exist, while a regular game set only has one such tile. The Unicode range for dominoes is U+1F030–U+1F09F. The naming pattern in Unicode is, by example, U+1F03B 🀻 DOMINO TILE HORIZONTAL-01-03. Few fonts are known to support these glyphs.[23] While the complete domino set has only 28 tiles, for printing layout reasons, the Unicode set needs both horizontal and vertical forms for each tile, plus the 01-03 (plain) 03-01 (reversed) pairs, and generic backsides.

| Domino Tiles[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1F03x | 🀰 | 🀱 | 🀲 | 🀳 | 🀴 | 🀵 | 🀶 | 🀷 | 🀸 | 🀹 | 🀺 | 🀻 | 🀼 | 🀽 | 🀾 | 🀿 |

| U+1F04x | 🁀 | 🁁 | 🁂 | 🁃 | 🁄 | 🁅 | 🁆 | 🁇 | 🁈 | 🁉 | 🁊 | 🁋 | 🁌 | 🁍 | 🁎 | 🁏 |

| U+1F05x | 🁐 | 🁑 | 🁒 | 🁓 | 🁔 | 🁕 | 🁖 | 🁗 | 🁘 | 🁙 | 🁚 | 🁛 | 🁜 | 🁝 | 🁞 | 🁟 |

| U+1F06x | 🁠 | 🁡 | 🁢 | 🁣 | 🁤 | 🁥 | 🁦 | 🁧 | 🁨 | 🁩 | 🁪 | 🁫 | 🁬 | 🁭 | 🁮 | 🁯 |

| U+1F07x | 🁰 | 🁱 | 🁲 | 🁳 | 🁴 | 🁵 | 🁶 | 🁷 | 🁸 | 🁹 | 🁺 | 🁻 | 🁼 | 🁽 | 🁾 | 🁿 |

| U+1F08x | 🂀 | 🂁 | 🂂 | 🂃 | 🂄 | 🂅 | 🂆 | 🂇 | 🂈 | 🂉 | 🂊 | 🂋 | 🂌 | 🂍 | 🂎 | 🂏 |

| U+1F09x | 🂐 | 🂑 | 🂒 | 🂓 | ||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Historic domino competitions

- Col. Henry T. Titus vs. Capt. Clark Rice for the naming of Titusville, Florida.[24]

See also

References

- Lo, Andrew. "The Game of Leaves: An Inquiry into the Origin of Chinese Playing Cards," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 63, No. 3 (2000): 389-406.

- Rodney P. Carlisle (2 April 2009). Encyclopedia of Play. SAGE. p. 181. ISBN 978-1-4129-6670-2. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- "Pink Dominoes". www.kiplingsociety.co.uk. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- A domino is a kind of hood worn by the canons of a cathedral church. Later, the name was given to a mourning-veil for women and later still to half-masks worn by women when travelling or at a masquerade, for disguise. A domino was a masquerade-dress worn for disguise by ladies and gentlemen, and consisting of an ample cloak or mantle with wide sleeves and a hood removable at pleasure. It was usually made of black silk, but sometimes of other colours and materials.[The Probert Encyclopaedia]

- "General Western Domino Attributes". Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Example of a double-18 domino set using Arabic numerals. Retrieved 29 March 2020

- 乔光辉、郭威、王骏. 《宣和牌谱》瞿佑作辨伪 (in Chinese). 《中华文化论坛》2009年01期. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Pickover (2002), 141.

- Lo, Andrew (2004) 'China's Passion for Pai: Playing Cards, Dominoes, and Mahjong.' In: Mackenzie, C. and Finkel, I., (eds.), Asian Games: The Art of Contest. New York: Asia Society, pp. 224.

- Lo, Andrew (2003). "Pan Zhiheng's 'Xu Yezi Pu' - Part 2". The Playing-Card. 31 (6): 281–284.

- Hoyle, Edmond; Dawson, Lawrence Hawkins (1950). Hoyle's games modernized. Routledge & Kegan Paul.. Republished 1994 by Wordsworth Editions.

- Kelley, Jennifer A.; Lugo, Miguel (2003). The Little Giant Book of Dominoes. Sterling. ISBN 1-4027-0290-6.

- "The Mathematics of Dominoes". Pagat.com. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- Squareman, Clarence (1916). "My Book of Indoor Games".

- "Bergen". domino-games.com.

- "Bergen". pagat.com.

- "Domino Glossary". domino-play.com. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Morehead, Albert Hodges; Hoyle, Edmond; Frey, Richard L.; Mott-Smith, Geoffrey (1991). The New Complete Hoyle. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-24962-4.

- "Domino computer - Everything2.com". everything2.com. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- David Johnston. "Domino computers". Archived from the original on 16 August 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "World domino record set on TV". BBC News. 15 November 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- "Unicode Version 5.1 Released" (Press release). Unicode Consortium. 4 April 2008. Archived from the original on 27 January 2009.

- "Fontsupport". Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- "City of Titusville History". City of Titusville, Florida.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.

Further reading

- * Pickover, Clifford A. (2002). The Zen of Magic Squares, Circles, and Stars. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11597-4.