Internal resistance to apartheid

Internal resistance to apartheid in South Africa originated from several independent sectors of South African society and took forms ranging from social movements and passive resistance to guerrilla warfare. Mass action against the ruling National Party government, coupled with South Africa's growing international isolation and economic sanctions, were instrumental in leading to negotiations to end apartheid, which began formally in 1990 and ended with South Africa's first multiracial elections under a universal franchise in 1994.[6][4]

| Internal resistance to apartheid | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

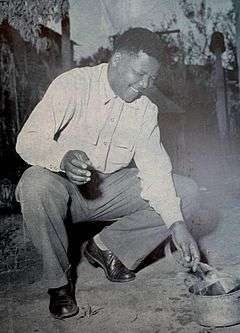

Nelson Mandela burns his passbook in 1960 as part of a civil disobedience campaign. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

APLA (PAC) ARM SAYRCO UDF (non-violent resistance only)[4] |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 21,000 dead as a result of political violence (1948-94)[5] | |||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

|

People

|

|

Places

|

|

Apartheid was adopted as a formal South African government policy by the National Party (NP) following their victory in the 1948 general election.[7] From the early 1950s, the African National Congress (ANC) initiated its Defiance Campaign of passive resistance.[1] Subsequent civil disobedience protests targeted curfews, pass laws, and "petty apartheid" segregation in public facilities. Some anti-apartheid demonstrations resulted in widespread rioting in Port Elizabeth and East London in 1952, but organised destruction of property was not deliberately employed until 1959.[8] That year, anger over pass laws and environmental regulations perceived as unjust by black farmers resulted in a series of arsons targeting sugarcane plantations.[8] Organisations such as the ANC, the South African Communist Party, and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) remained preoccupied with organising student strikes and work boycotts between 1959 and 1960.[8] Following the Sharpeville massacre, some anti-apartheid movements, including the ANC and PAC, began a shift in tactics from peaceful non-cooperation to the formation of armed resistance wings.[9]

Mass strikes and student demonstrations continued into the 1970s, charged by growing black unemployment, the unpopularity of the South African Border War, and a newly assertive Black Consciousness Movement.[10] The brutal suppression of the 1976 Soweto uprising radicalised a generation of black activists and greatly bolstered the strength of the ANC's guerrilla force, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK).[11] From 1976 to 1987 MK carried out a series of successful bomb attacks targeting government facilities, transportation lines, power stations, and other civil infrastructure. South Africa's military often retaliated by raiding ANC safe houses in neighbouring states.[12]

The National Party made several attempts to reform the apartheid system, beginning with the Constitutional Referendum of 1983. This introduced a Tricameral Parliament, which allowed for some parliamentary representation of Coloureds and Indians, but continue to deny political rights to black South Africans.[4] The resulting controversy triggered a new wave of anti-apartheid social movements and community groups which articulated their interests through a national front in politics, the United Democratic Front (UDF).[4] Simultaneously, inter-factional rivalry between the ANC, the PAC, and the Azanian People's Organisation (AZAPO), a third militant force, escalated into sectarian violence as the three groups jockeyed for influence.[13] The government took the opportunity to declare a state of emergency in 1986 and detain thousands of its political opponents without trial.[14]

Secret bilateral negotiations to end apartheid commenced in 1987 as the National Party reacted to increased external pressure and the atmosphere of political unrest.[4] Leading ANC officials such as Govan Mbeki and Walter Sisulu were released from prison between 1987 and 1989, and in 1990 the ANC and PAC were formally delisted as banned organisations by President F. W. de Klerk, and Nelson Mandela released from prison. The same year, MK reached a formal ceasefire with the South African Defence Force.[13] Further apartheid laws were abolished on 17 June 1991, and multiparty negotiations proceeded until the first multi-racial general election held in April 1994.[15]

African National Congress

Although its creation predated apartheid, the African National Congress (ANC) became the primary force in opposition to the government after its moderate leadership was superseded by the organisation's more radical Youth League (ANCYL) in 1949. Led by Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo, elected to the ANC's National Executive that year, the ANCYL advocated a radical black nationalist programme that combined the Africanist ideas of Anton Lembede with those of Marxism. They brought the notion that white authority could only be overthrown through mass campaigns. The ideals of the ANC and ANCYL are stated in the ANC official web site and state, concerning the "Tripartite Alliance", "The Alliance is founded on a common commitment to the objectives of the National Democratic Revolution, and the need to unite the largest possible cross-section of South Africans behind these objectives." This cites the actionable intent, their goal to end oppression.[16]

Once the ANCYL had taken control of the ANC, the organisation advocated a policy of open defiance and resistance for the first time. This unleashed the 1950s Programme of Action, instituted in 1949, which laid emphasis on the right of the African people to freedom under the flag of African Nationalism. It laid out plans for strikes, boycotts, and civil disobedience, resulting in occasionally violent clashes, with mass protests, stay-aways, boycotts and strikes predominating. The 1950 May Day stay-away was a strong, successful expression of black grievances.[17]

In 1952 the Joint Planning Council, made up of members from the ANC, the South African Indian Congress as well as the Coloured People's Congress, agreed on a plan for the defiance of unfair laws. They wrote to the Prime Minister, DF Malan and demanded that he repeal the Pass Laws, the Group Areas Act, the Bantu Administration Act and other legislation, warning that refusal to do so would be met with a campaign of defiance. The Prime Minister was haughty in his rejoinder, referring the Council to the Native Affairs Department and threatening to treat insolence callously.[18]

The Programme of Action was launched with the Defiance Campaign in June 1952. By defying the laws, the organisation hoped for mass arrests that would overwhelm the government. Nelson Mandela led a crowd of 50 men down the streets of a white area in Johannesburg after the 11 pm curfew that forbade black peoples' presence. The group was apprehended, but the rest of the country followed its example. Defiance spread throughout the country and black people disregarded racial laws by, for example, walking through "whites only" entries. At the campaign's zenith, in September 1952, more than 2,500 people from 24 different towns had been arrested for defying various laws. After five months, the African and Indian Congresses opted to call off the campaign because of the increasing number of riots, strikes and heavier sentences on those who took part. During the campaign, almost 8,000 black and Indian people had been detained.[19] At the same time, however, ANC membership grew from 7,000 to 100,000, and the number of subdivisions went from 14 at the start of the campaign to 87 at its end. There was also a change in leadership. Shortly before the campaign's end, Albert Luthuli was elected as the new ANC president.[20]

By the end of the campaign, the government was forced to temporarily relax its apartheid legislation. Once things had calmed down, however, the government responded with an iron fist, taking several supreme measures, among which were the Unlawful Organisations Act, the Suppression of Communism Act, the Public Safety Act and the Criminal Procedures Act.[21] The Criminal Law Amendment Act No 8 stated that "[Any person who in any way whatsoever advises, encourages, incites, commands, aids or procures any other person ... or uses language calculated to cause any other person to commit an offence by way of protest against the law... shall be guilty of an offence".[22] In December 1952, Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and 18 others were tried under the Suppression of Communism Act for leading the Defiance Campaign. They received nine months' imprisonment, suspended for two years.[23]

The government also tightened the regulation of separate amenities. Protesters had argued to the courts that different amenities for different races ought to be of an equal standard. The Separate Amenities Act removed the façade of mere separation; it gave the owners of public amenities the right to bar people on the basis of colour or race and made it lawful for different races to be treated inequitably. Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, Albert Luthuli and other famous ANC, Indian Congress and trade union chiefs activities were all proscribed under the Suppression of Communism Act. The proscription meant that the headship was now restricted to its homes and adjacent areas and they were banned from attending public gatherings.[24]

Meanwhile, on the global stage, India demanded that apartheid be challenged by the United Nations, leading to the establishment of a UN commission on apartheid.[25]

Though under increasing restrictions, the movement was still able to struggle against the oppressive instruments of the state. More importantly, collaboration between the ANC and NIC had increased and strengthened through the Defiance Campaign. Support for the ANC and its endeavours increased.[26] On 15 August 1953, at the Cape ANC conference in Cradock Professor Z. K. Matthews proposed a national convention of the people to study the national problems on an all-inclusive basis and outline a manifesto of amity.[27] In March 1954, the ANC, the South African Indian Congress (SAIC), the Coloured People's Congress, the South African Congress of Democrats (SACOD) and the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) met and founded the National Action Council for the Congress of the People.[28] Delegates were drawn from each of these establishments and a nationwide organiser was assigned. A campaign was publicised for the drafting of a freedom charter, and a call was made for 10,000 volunteer to help with the conscription of views from across the country and the organisation of the Congress of the People. Demands were documented and sent to the local board of the National Action Council in preparation for drafting the Charter.[29]

The Congress of the People was held from 25 to 26 June 1955 in Kliptown, just south of Johannesburg.[30] Under the attentive gaze of the police, 3,000 delegates gathered to revise and accept the Freedom Charter that had been endorsed by the ANC's National Executive on the eve of the Congress. Among the organisations present were the Indian Congress and the ANC. The Freedom Charter articulated a vision for South Africa radically different from the partition policy of apartheid, emphasising that South Africa should be a just and non-racial society. It called for a one-person-one-vote democracy within a single unified state and stated that all people should be treated equally before the law, that land should be "shared among those who work it" and that the people should "share in the country's wealth" — a statement often been interpreted as a call for socialist nationalisation.[31] The congress delegates had consent;ed to almost all the sections of the charter when the police announced that they suspected treason and recorded the names and addresses of all those present.[32]

In 1956, the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) was founded and led by Lilian Ngoyi , Helen Joseph and Amina cachalia.[33] On 9 August that year, the women marched on the Union Buildings in Pretoria, protesting against the pass laws.[34] On the morning of 5 December 1956, however, the police detained 156 Congress Alliance leaders. 104 African, 23 white, 21 Indian and eight Coloured people were charged with high treason and plotting a violent overthrow of the state, to be replaced by a communist government. The charge was based on statements and speeches made during both the Defiance Campaign and the Congress of the People. The Freedom Charter was used as proof of the Alliance's communist intent and their conspiracy to oust the government. The State relied greatly on the evidence of Professor Arthur Murray, an ostensible authority on Marxism and Communism. His evidence was that the ANC papers were full of such communist terms as "comrade" and "proletariat", often found in the writings of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin. Halfway through the drawn-out trial, charges against 61 of the accused were withdrawn, and, five years after their arrest, the remaining 30 were acquitted after the court held that the state had failed to prove its case.[35]

Resistance goes underground in the 1960s

The Sharpeville Massacre

In 1958 a group of disenchanted ANC members broke away from the ANC and formed the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC)in 1959. First on the PAC's agenda was a series of nationwide demonstrations against the pass laws.[36] The PAC called for blacks to demonstrate against pass books on 21 March 1960. One of the mass demonstrations organised by the PAC took place at Sharpeville, a township near Vereeniging. Estimates of the size of the crowd is 20,000 people[37]. The crowd converged on the Sharpeville police station, singing and offering themselves up for arrest for not carrying their pass books. A group of about 300 police panicked and opened fire on the demonstrators after the crowd trampled down the fence surrounding the police station. They killed 69 people and injured 186. All the victims were black, and most of them had been shot in the back.[38] Many witnesses stated that the crowd was not violent, but Colonel J. Pienaar, the senior police officer in charge on the day, said, "Hordes of natives surrounded the police station. My car was struck with a stone. If they do these things they must learn their lesson the hard way". The event became known as the Sharpeville massacre. In its aftermath the government banned the African National Congress (ANC) and the PAC.[39][40]

Beginning of the guerrilla campaign

The Sharpeville Massacre had the effect of persuading several anti-apartheid movements that nonviolent civil disobedience alone was ineffective at encouraging the National Party government to seek reform.[41] The resurgent tide of armed revolutions in many developing nations and European colonial territories during the early 1960s had the effect of persuading ANC and PAC leaders that nonviolent civil disobedience should be complemented by acts of insurrection and sabotage.[42] Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, were instrumental in persuading the ANC's executive to adopt armed struggle.[41] Mandela had first advocated this option during the Defiance Campaign of 1952, but his proposal was rejected by his fellow activists as being too radical.[42] However, with the subsequent success of revolutionary struggles in Cuba, French Indochina, and French Algeria, the ANC executive became increasingly more open to suggestions by Mandela and Sisulu that the time was ripe for armed struggle.[42]

From 1961 to 1963 the ground in South Africa was slowly being readied for armed revolution. A hierarchal network of covert ANC cells was created for underground operations, military aid solicited from sympathetic African states and the Soviet Union, and a guerrilla training camp established in Tanganyika.[42] In June 1961 the Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) had been set up by the ANC to coordinate underground militant activity throughout South Africa. By the end of 1962 the ANC had established an MK high command consisting of Mandela, Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, and prominent South African Communist Party (SACP) activist Joe Slovo.[41] Slovo and the SACP were instrumental in bolstering MK and developing its tactics for guerrilla warfare, inciting insurrection, and urban sabotage.[41] White SACP members such as Jack Hodgson, who had served in the South African Army during World War II, were instrumental in training MK recruits.[43] The SACP was also able to secure promises of military aid from the Soviet Union for the fledging guerrilla army, and purchased Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, just outside Johannesburg, to serve as MK's headquarters.[44]

Throughout the 1960s, MK was still a relatively small unit of poorly equipped guerrilla fighters incapable of taking significant action against the South African security forces.[45] Success of the MK's strategy hinged upon its ability to stoke the anger of a politically conscious black underclass and its armed struggle was essentially a strategic attempt at mass socialisation.This reflected the principles of Leninist vanguardism which heavily influenced SACP and to a lesser extent, ANC political theory. MK commanders hoped that through their actions, they could appeal to the masses and inspire a popular uprising against the South African regime.[42] A popular uprising would compensate for the MK's weaknesses as it offered a way to defeat the National Party politically without having to engage in a direct military confrontation which the guerrillas would have no hope of winning.[46]

On December 16, 1961, MK operatives bombed a number of public facilities in several major South African cities, namely Johannesburg, Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, and Durban.[47] This programme of controlled sabotage was timed to coincide with the Day of the Vow, the anniversary of an important battle between the voortrekkers and the Zulu Kingdom in 1838.[42] Over the next eighteen months, MK carried out 200 acts of sabotage, mostly targeting pass offices, power pylons, and police stations.In October 1962 the ANC publicly declared responsibility for the sabotage campaign and acknowledged the existence of MK.[41]

Mandela began planning for MK members to be given military training outside South Africa and managed to slip past authorities as he himself moved in and out of the country, earning him the moniker "The Black Pimpernel". Mandela initially resisted arrest within South Africa, but in August 1962, after receiving some inside information, the police put up a roadblock and captured him. MK's success declined after this, and the police infiltrated the organisation.[48]

In July 1963, the police found the location of the MK headquarters at Lilliesleaf. In , they raided the farm and arrested many major leaders of the ANC and MK, including Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and Ahmed Kathrada. They were detained and indicted with sabotage and attempting to bring down the government. At the same time, police collected evidence to be used in the trial, which enabled them to arrest other such people, like Denis Goldberg. Especially harmful was the information on Operation Mayibuye (Operation Comeback), a plan for bringing exiles back into the country. It also revealed that MK was planning to use guerrilla warfare.[49]

The PAC's secretive martial arm was called Poqo, meaning "go it alone". Poqo was prepared to take lives in the quest for liberation. It murdered whites, police informants and black people who supported the government. It sought to arrange a national revolution to conquer the white government, but poor organisation and in-house nuisances crippled the PAC and Poqo.[50]

The PAC did not have adequate direction. Many PAC principals were taken into custody on 21 March 1960, and those released were hampered by bans. When Robert Sobukwe (jailed following the Sharpeville massacre) was discharged from Robben Island in 1969, he was placed under house arrest in Kimberley until he died in 1978. Police repeatedly lengthened his incarceration through the "Sobukwe clause", which permitted the state to detain people even after they had served their sentences.[51]

The PAC's management difficulties also existed in exile. When they were outlawed, PAC leaders set up headquarters, in among places, Dar es Salaam, London and the United States.[52] In 1962, Potlako Leballo left the country for Maseru, Basutoland, and became the PAC's acting president.[53] Soon after he was elected as acting president, he make public statement that he will launch an attack to South African Police with an army of 150.000 cadres. A few days after that statement, he send two PAC women couriers, Cynthia Lichaba and Thabisa Lethala to post letters in Ladybrand, a South African town close Lesotho. The letters contained instructions and details of Poqo cadres. When Basutoland special branch intelligence in Maseru warned the South Africans that two female PAC couriers had crossed into South Africa to deliver letters. The two girl was arrested and Basutoland police confiscated correspondence addressed to poqo cells which was contained adress of the cell. A wave of arrests followed, and 3,246 PAC and Poqo members went to jail. [54]

In 1968, PAC was eventually expelled from Maseru (where it was allied to the opposition Basutoland Congress Party) and Zambia (which was friendlier to the ANC).[55] All in all, MK ran a far more successful guerrilla campaign than Poqo. Between 1974 and 1976 Leballo and Ntantala trained the Lesotho Liberation Army (LLA) and Azanian People's Liberation Army (APLA) in Libya. American pressures split the PAC into a "reformist-diplomatic" group under Sibeko, Make, and Pokela and a Maoist group under Leballo based in Ghana. APLA was destroyed by the Tanzanian military at Chunya on 11 March 1980 for refusing to accept the reformist-diplomatic leadership by Make. Leballo was influential in the South African 1985 student risings and pivotal in removing Leabua Jonathan's regime in Lesotho, the stress of which caused his death. The PAC never recovered from the 1980 massacre of Leballo's troops and his death and won a paltry 1.2% of the vote in the 1994 South African election.[56]

The widely publicised Rivonia Trial began in October 1963. Ten men stood accused of treason, trying to depose the government and sabotage. Nelson Mandela was tried, along with those arrested at Lilliesleaf and another 24 co-conspirators. Many of these people, however, had already fled the country, Tambo being but one.[57]

The ANC used the lawsuit to draw international interest to its cause. During the trial, Mandela gave his legendary "I am prepared to die" speech.[58] In June 1964, eight were found guilty of terrorism, sabotage, planning and executing guerrilla warfare, and working towards an armed invasion of the country. The treason charge was dropped. All eight were sentenced to life imprisonment. They did not get the death penalty, as this hazarded too much international criticism. Goldberg was sent to the Pretoria Central Prison, and the other seven were all banished to the prison on Robben Island. Bram Fischer, the defence trial attorney, was himself arrested and tried shortly thereafter. The instructions that Mandela gave to make MK an African force were ignored: it continued to be organised and led by the SACP.[57] The trial was condemned by the United Nations Security Council, and was a major force in the introduction of international sanctions against the South African government. After Sharpeville the ANC and PAC were banned.[59] The South African Communist Party denied it existed, having dissolved in 1950 to escape banning as the CPSA. Leaders like Mandela and Sobukwe were either in jail or in exile.Consequently, there were serious mutinies in Angolan camps by Soweto and Cape student recruits angry at the corrupt and brutal consequences of minority control.[60]

By incarcerating leaders of MK and the ANC, the government was able to break the potency of the ANC within South Africa's borders, and greatly affect its efficiency outside of them. The ANC faced many problems in the aftermath of the Rivonia Trial, its inner administration cruelly afflicted.[61] Thus, by 1964, the ANC went underground and began guerilla activities from bases abroad.At the end of the 1960s, new organisations and ideas would form to confront apartheid. The next key act of opposition would come only in 1976, however, with the Soweto uprising.[62]

The government's effort at defeating all opposition had been effective. The State of Emergency was de-proclaimed; the economy boomed; and the government began implementing apartheid by building the infrastructures of the ten separate Homelands, and relocating blacks into these homelands. In 1966, Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd was stabbed to death in parliament, but his policies continued under B.J. Vorster and later P.W. Botha.[63]

Black Consciousness Movement

Prior to the 1960s, the NP government had been most effective in crushing anti-apartheid opposition within South Africa by outlawing movements like the ANC and PAC, and driving their leaders into exile or captivity. This planted the seeds for the struggle, particularly at such tertiary-education organisations as the University of the North and Zululand University. These institutions were fashioned out of the Extension of University Education Act of 1959, which guaranteed that black and white students would be taught individually and inequitably.

After the banning of the ANC and PAC, and the Rivonia Trial, the struggle within South Africa had been dealt a stern blow. The age bracket that had seen the Sharpeville massacre had become apathetic in its gloom and despair. This changed in the late 1960s and most notably from the mid-1970s, when new devotion came from the latest, more radical generation. During this epoch, new anti-apartheid ideas and establishments were created, and they gathered support from across South Africa.

The surfacing of the South African Black Consciousness Movement was influenced by its American equivalent, the American Black Power movement, and directors such as Malcolm X. African heads like Kenneth Kaunda also stirred ideas of autonomy and Black Pride by means of their anti-colonialist writings. Scholars grew in assurance and became far more candid about the NP's bigoted policies and the repression of the black people.

During the 1970s, resistance gained force, first channelled through trade unions and strikes, and then spearheaded by the South African Students' Organisation, under the charismatic leadership of Steve Biko. A medical student, Biko was the main force behind the growth of South Africa's Black Consciousness Movement, which stressed the need for psychological liberation, black pride, and non-violent opposition to apartheid.[64]

Founded by Biko, the BC faction materialised out of the ideas of the civil rights movement and Black Power movement in the USA. The motto of the movement was "Black is Beautiful", first made popular by boxer Mohammed Ali. BC endorsed black pride and African customs, and did much to alter feelings of inadequacy, while also raising awareness of the fallacy of blacks being seen as inferior. It defied practices and merchandise that were meant to make black people "whiter", such as hair straighteners and skin lighteners. Western culture was toured as destructive and alien to Africa. Black people became conscious of their own distinctive identity and self-worth, and grew more outspoken about their right to freedom.

The National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) was the first organisation to represent students in South Africa, but it had a principally white membership, and black students saw this as an impediment. White students had concerns more scholastic than political, and, although the administration was multi-racial, it was not tackling many of the issues of the mounting number of black students since 1960. This resulted in the 1967 creation of the University Christian Movement (UCM), an organisation rooted in African-American philosophy.

In July 1967, the annual NUSAS symposium took place at Rhodes University in Grahamstown. White students were permitted to live on university grounds, but black students were relegated to accommodation further away in a church vestibule. This later led to the creation of the South African Students Organisation (SASO), under Steve Biko, in 1969.

The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was an umbrella organisation for groups such as SASO. It was created in 1967, and among its members were the Azanian People's Organisation, the black Community Programme (which directed welfare schemes for blacks), the Black People's Convention (which, at first, attempted to unite charitable associations like that for the Education and Cultural Advancement of African People of South Africa) and the South African Students Movement (SASM), which represented high-school learners. The BPC finally expanded into a political administration, with Steve Biko as its honorary president.

When the BCM's principles were illuminated, a number of fresh organisations, staunch in their endorsement of black liberation, came into being. The Azanian People's Organisation was only launched in 1978, a long time after the birth of the Black Consciousness Movement, as a medium for its message.

The BCM drew most of its backing from high schools and tertiary institutions. Black Consciousness ethics were crucial in lifting consciousness amongst black people of their value and right to a better existence, along with the need to insist on these. The BCM's non-violent approach subsided in favour of a more radical element as its resolve to attain liberty was met with state hostility.

After the carnage in Soweto the ANC's Nelson Mandela grudgingly concurred that bloodshed was the only means left to convince the NP to accede to commands for an end to its apartheid policy. A subversive plan of terror was mapped out, with Steve Biko and the BCM to the fore. The Black Consciousness Movement and other opinionated elements were prohibited during the 1970s because the government saw them as dangerous. Black Consciousness in South Africa adopted a drastic theory, much like socialism, as the liberation movement progressed to challenging class divisions and shifting from an ethnic stress to focusing more on non-racialism. The BCM became more worried about the destiny of the black people as workers, believing that "economic and political exploitation has reduced the black people into a class".

With Black Consciousness increasing throughout black communities, a number of other organisations were formed to combat apartheid. In 1972, the Black People's Convention was founded, and the black Allied Worker's Union, formed in 1973, focused on black labour matters. The black community programmes gave attention to the more global issues of black communities. School learners began to confront the Bantu education policy, designed to prepare them to be second-class citizens. They created the South African Student's Movement (SASM). It was particularly popular in Soweto, where the 1976 insurrection against Bantu Education would prove to be a crossroads in the fight against apartheid.

Taken into custody on 18 August 1977, Steve Biko was brutally tortured by unidentified security personnel until he lapsed into a coma. He went for three days without medical treatment and finally died in Pretoria. At the subsequent inquest, the magistrate ruled that no-one was to blame, but the South African Medical Association eventually took action against the doctors who had failed to treat Biko.

There was tremendous reaction both within and outside South Africa. Foreign countries imposed even more stringent sanctions, and the United Nations imposed an arms embargo. Young blacks inside South Africa committed themselves even more fervently to the struggle against apartheid, under the catchphrase "Liberation before education". Black communities became highly politicised.

The Black Consciousness Movement began to change its focus during the 1980s from being on issues of nation and community to issues of class and, perhaps as a result, had far less of an impact than in the mid-'seventies. Still, there is some evidence to suggest that it retained at least some influence, particularly in workers' organisations.

The role of Black Consciousness could be clearly seen in the approach of the National Forum, which believed that the struggle ought to hold little or no place for whites. This ideal, of blacks leading the resistance campaign, was an important aim of the traditional Black Consciousness groups, and it shaped the thinking of many 'eighties activists, most notably the workforce. Furthermore, the NF focused on workers' issues, which became more and more important to BC supporters.

The Azanian People's Organisation was the leading Black Consciousness group of the 1980s. It got most of its support from young black men and women—many of them educated at colleges and universities. The organisation had a lot of support in Soweto and also amongst journalists, helping to popularise its views. It focused, too, on workers' issues, but it refused to form any ties with whites.

Although it did not achieve quite the same groundswell of support that it had in the late 1970s, Black Consciousness still influenced the thinking of a few resistance groups.

Soweto uprising

In 1974 the Afrikaans Medium Decree forced all black schools to use Afrikaans and English in a 50–50 mix as languages of instruction. The intention was to forcibly reverse the decline of Afrikaans among black Africans. The Afrikaner-dominated government used the clause of the 1909 Constitution that recognised only English and Afrikaans as official languages as pretext to do so.

The decree was resented deeply by blacks as Afrikaans was widely viewed, in the words of Desmond Tutu, then Dean of Johannesburg as "the language of the oppressor". Teacher organisations such as the African Teachers Association of South Africa objected to the decree.

The resentment grew until 30 April 1976, when children at Orlando West Junior School in Soweto went on strike, refusing to go to school. Their rebellion then spread to many other schools in Soweto. Students formed an Action Committee (later known as the Soweto Students' Representative Council) that organised a mass rally for 16 June 1976. The protest was intended to be peaceful.

In a confrontation with police, who had barricaded the road along the intended route, stones were thrown. Attempts to disperse the crowd with dogs and tear gas failed; when the police saw they were surrounded by the students, they fired shots into the crowd, at which point pandemonium broke out.

In the first day of rioting 23 people were killed in escalating violence. The following day 1,500 heavily armed police officers were deployed to Soweto. Crowd control methods used by South African police at the time included mainly dispersement techniques, and many of the officers shot indiscriminately, killing 176 people, most by police violence.[65][66]

Student organisations

Student organisations played a significant role in the Soweto uprisings, and after 1976 protests by school children became frequent. There were two major urban school boycotts, in 1980 and 1983. Both involved black, Indian and coloured children, and both went on for months. There were also extended protests in rural areas in 1985 and 1986. In all of these areas, schools were closed and thousands of students, teachers and parents were arrested.

South African Students Movement

Students from Orlando West and Diepkloof High Schools (both in Soweto) created the African Students Movement in 1970. This spread to the Eastern Cape and Transvaal, drawing other high schools. In March 1972, the South African Students Movement (SASM) was instituted.

SASM gave support to its members with school work and exams, and with progress from lower school levels to university. Security forces pestered its members continually until, in 1973, some of its leaders fled the country. In 1974 and 1975, some affiliates were captured and tried under the Suppression of Communism and Terrorism Acts. This flagged the SASM's progress. Many school headmasters and -mistresses forbade the organisation from playing a role in their schools.

When the Southern Transvaal local Bantu Education Department concluded that all junior secondary black students had to be taught in Afrikaans in 1974, SASM limbs at Naledi High School and Orlando West Secondary Schools opted to vent their grievances on school books and refused to attend their schools This form of struggle spread fast to other schools in Soweto and hit boiling point around 8 June 1976. When law enforcement attempted to arrest a regional SASM secretary, they were stoned and had their cars torched.

On 13 June 1976, nearly 400 SASM associates gathered and chose to start a movement for mass action. An Action Committee was shaped with two agents from each school in Soweto. This board became known as the Soweto Students' Representatives Council (SSRC). The protest was set aside for 16 June 1976, and the organisers were determined only to use aggression if they were assaulted by the police.

National Union of South African Students

After the Sharpeville Massacre, some black student organisations came out but were short-lived under state proscription and antagonism from university powers. They were also unsuccessful in co-operating effectively with one another, resulting in a dearth of harmony and force.

By 1963, one of the few envoys for tertiary students was the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS). Although the organisation was meant to be non-racial and anti-government, it was made up primarily of white English students from customarily broad-minded universities such as those in Natal, Cape Town, the Witwatersrand and Grahamstown. These students were had compassion for the effort against the state. By 1967, however, NUSAS was forbidden from functioning on black universities, making it almost impossible for black Student Representative Councils to join the union.

South African Students Organisation

Growing displeasure among black students and the expansion of Black Consciousness led to the incarnation of the South African Students Organisation (SASO) at Turfloop. In July 1969, Steve Biko became the organisation's inaugural head. This boosted the mood of the students and the Black Consciousness Movement. By means of the unified configuration of SASO, the principles of Black Consciousness came to the forefront as a fresh incentive for the strugglers.

Congress of South African Students

The Congress of South African Students (COSAS) was aimed at co-ordinating the education struggle and organised strikes, boycotts and mass protests around community issues. After 1976 it made a number of demands from the Department of Education and Training (DET), including the scrapping of matric examination fees. It barred many DET officials from entering schools, demanded that all students pass their exams – "pass one, pass all"—and disrupted exams.

National Education Crisis Committee

In 1986, following school boycotts, the National Education Crisis Committee (NECC) was constituted from parents, teachers and students. It encouraged students to return to their studies, taking on forms of protest less disruptive to their education. Consumer boycotts were recommended instead and teachers and students were encouraged to work together to develop an alternative education system.

Trade union movement

Following the start of apartheid, South Africa was flourishing economically, due to its newly found trade relations. Products such as gold and coal were being traded along the nation's coastal lines, to western countries. The products being traded, were all mined by the black labour workers, who were split up by the Bantustan law. This law created different tribes of black South Africans, each who respectively would work in the same area and perform certain labour acts. This was strategic as it allowed the white people to direct labour easily.[67]

Respectively, in 1973 labour action in South Africa was renewed, as a result of the numerous strikes in Durban. Abuse of black workers was common, and, as a consequence, many black people were paid less than a living wage. In January, 2,000 workers of the Coronation Brick and Tile Company went on strike for a pay raise (from under R10 to R20 a week), incorporating Gandhis views of civil resistance into their rebellions.[68] The strike drew a lot attention and encouraged other workers to strike. Strikes for higher wages, improved working conditions and the end of exploitation occurred throughout this period. Inspired by the brick and tile workers, other industrial and municipal workers followed in suit and walked off their jobs. A month later, 30,000 black labour workers were on strike in Durban alone. The entire apartheid system, relied on black labour workers to keep its economy growing, thus the strikes strategically disrupted the system of power. Not only did these strikes distort the nation's economy, they also inspired students to strike on their own. The Durban labour strikes were a foundation for multiple rebellions such as the ‘Soweto Uprising’.[69]

Police employed tear gas and violence against the strikers, but could not apprehend the masses of people involved. The strikers never chose individuals to stand for them, because these people would be the first to be detained. Blacks were not permitted trade unions, which meant that the government could not act against any particular individuals. Strikes usually concluded when income boosts were tendered, but these were generally lower than had initially been insisted upon.

The Durban strikes soon extended to other parts of the country. 1973 and 1974 saw a countrywide amplification of labour opposition. There was also an increasingly buoyancy among black workers as they found that the state did not retort as harshly as they had expected. They thus began to form trade unions, even though these remained illegitimate and unofficial.

After 1976, trade unions and their workers began to play a massive role in the fight against apartheid. With their thousands of members, the trade unions had great strength in numbers, and this they used to their advantage, campaigning for the rights of black workers and forcing the government to make changes to its apartheid policies. Importantly, trade unions filled the gap left by banned political parties. They assumed tremendous importance because they could act on a wide variety of issues and problems for their people—and not only work-related ones, as links between work issues and broader community grievances became more palpable.

Fewer trade-union officials (harassed less by the police and army) were jailed than political leaders in the townships. Union members could meet and make plans within the factory. In this way, trade unions played a pivotal role in the struggle against apartheid, and their efforts generally had wide community support.

In 1979, one year after Botha's accession to power, black trade unions were legalised, and their role in the resistance struggle grew to all-new proportions. Prior to 1979, black trade unions had had no legal clout in dealings with employers. All strikes that took place were illegal, but they did help to establish the trade unions and their collective cause. Although the legalisation of black trade unions gave workers the legal right to strike, it also gave the government a degree of control over them, as they all had to be registered and hand in their membership records to the government. They were not allowed to support political parties either, and it goes without saying that some trade unions did not comply.

Later in 1979, the Federation of South African Trade Unions (FOSATU) was formed as the first genuinely national and non-racial trade union federation in South Africa. It was followed by the Council of Unions of South Africa (CUSA), which was influenced strongly by the ideas of Black Consciousness and wanted to work to ensure black leadership of unions.

The establishment of the trade union federations led to greater unity amongst the workers. The tremendous size of the federations gave them increased voice and power. 1980 saw thousands of black high-school and university students boycotting their schools, and a country-wide protest over wages, rents and bus fares. In 1982, there were 394 strikes involving 141,571 workers. FOSATU and CUSA grew from a mere 70,000 members in 1979 to 320,000 by 1983, the year of the establishment of first the National Forum and then the UDF. Both of these had an important impact, but the latter was far more influential.

With the establishment of the new constitution in 1984, the biggest and longest black uprising exploded in the Vaal Triangle. COSAS and FOSATU organised the longest stay-away in South African history, and, all told, there were 469 strikes that year, amounting to 378,000 hours in lost business time.

In accordance with the State of Emergency in 1985, COSAS was banned and many UDF leaders arrested. A meeting between white business leaders and those of the ANC in Zambia brought about the formation of COSATU in 1985. The newly formed trade-union governing body, committed to improved working conditions and the fight against apartheid, organised a nationwide strike the following year, and a new State of Emergency was declared. It did not take long for COSATU's membership to grow to 500,000.

With South Africa facing a neigh-unprecedented shortage of skilled white labour, the government was forced to allow black people to fill the vacancies. This, in turn, led to an increase in spending on black, coloured and Indian education.

Still, there were divides amongst the trade-union faction, which had the membership of only ten per cent of the country's workforce. Not all trade unions joined the federations, while agricultural and domestic workers did not even have a trade union to join and were thus more liable. Nevertheless, by the end of this period, the unions had emerged as one of the most effective vehicles for black opposition.

Churches

The government's suppression of anti-Apartheid political parties limited their influence but not church activism. The government was far less likely to attack or arrest religious leaders, allowing them to potentially be more politically active in the struggle. The government did, however, take action against some churches.

Beyers Naudé left the pro-apartheid Dutch Reformed Church and founded the Christian Institute of Southern Africa with other theologians, including Albert Geyser, Ben Marais and John de Gruchy. Naudé, along with the Institute, were banned in 1977, but he later became the general secretary of the South African Council of Churches (SACC), a religious association that supported anti-apartheid activities. Significantly, it also refused to condemn violence as a means of ending apartheid.

Frank Chikane was another general secretary of the SACC. He was detained four times because of his criticism of the government and once allegedly had an attempt on his life, initiated by Adriaan Vlok, former Minister of Law and Order.

The charismatic Archbishop Desmond Tutu was yet another general secretary of the SACC. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts in 1984 and used his position and popularity to denounce the government and its policies. On 29 February 1988 Tutu, and a number of other church leaders, were arrested during a protest in front of the parliamentary buildings in Cape Town.[70]

Alan Boesak led the World Alliance of Reformed Churches (WARC). He was very influential in founding the UDF and was once jailed for a month after organising a march demanding the release of Nelson Mandela.

Although church leaders were not totally immune to prosecution, they were able to criticise the government more freely than the leaders of militant groups. They were pivotal in altering public opinion regarding apartheid policies.

A 1977 New York Times article reported that the Catholic Church in South Africa had caught up and in fact surpassed Protestant Churches by authorizing the admission of black students to previously all-white schools. This was done in disregard of South African law which required segregation. Protestant churches such as the Anglicans had generally followed a conciliatory approach of attempting to gain prior government approval. The Catholics also announced they were laying the groundwork to extend their approach to hospitals, homes and orphanages. In contrast, the Dutch Reformed Church still offered biblical justifications for segregation in 1977, although some reformers within this denomination challenged that.[71]

Mass Democratic Movement

The Mass Democratic Movement played a brief but very important role in the struggle. Formed in 1989, it was made up of an alliance between the UDF and COSATU, and organised a campaign aimed at ending segregation in hospitals, schools and beaches. The campaign proved successful and managed to bring segregation to an end. Some historians, however, argue that this occurred because the government had planned to end segregation anyway and did not, therefore, feel at all threatened by the MDM's action.

Later in 1989, the MDM organised a number of peaceful marches against the State of Emergency (extended to four years now) in the major cities. Even though these marches were illegal, no-one was arrested—evidence that apartheid was coming to an end and that the government's hold was weakening.

The MDM emerged only very late into the struggle, but it added to the effective resistance that the government faced. It organised a series of protests and further united the opposition movement. Certainly, it was characteristic of the "mass resistance" that characterised the 'eighties: many organisations united, dealing with different aspects of the fight against apartheid and its implications.

White resistance

While the majority of white South African voters supported the apartheid system for the first few decades, a minority fervently opposed it. Although assassination attempts against government members were rare, Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd, called the "architect of grand apartheid", suffered two attempts on his life (the second of which was successful) on the hands of David Pratt and Dimitri Tsafendas, both legally considered white (although Tsafendas had a mother from Portuguese East Africa). The moderate United Party of Jan Smuts (the official opposition in 1948–1977) initially opposed the Nationalists' programme of apartheid, having favoured the dismantling of racial segregation by the Fagan Commission, but eventually came to revert its policy and even criticised the NP government for "handing out" too much South African land to the bantustans. In parliamentary elections during the 1970s and 1980s between 15% and 20% of white voters voted for the liberal Progressive Party, whose main champion Helen Suzman for many years constituted the only MP consistently voting against apartheid legislation. Suzman's critics argue that she did not achieve any notable political successes, but helped to shore up claims by the Nationalists that internal, public criticism of apartheid was permitted. Suzman's supporters point to her use of her parliamentary privileges to help the poorest and most disempowered South Africans in any way she could.

Harry Schwarz was in minority opposition politics for over 40 years and was one of the most prominent opponents of the National Party and its policy of apartheid. After assisting in the 1948 general election, Schwarz and others formed the Torch Commando, an ex-soldiers' movement to protest against the disenfranchisement of the coloured people in South Africa. Beginning in the 1960s, when he was Leader of the Opposition in the Transvaal, he became well-known and achieved prominence as a race relations and economic reformist in the United Party. An early and powerful advocate of non-violent resistance, he signed the Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith with Mangosuthu Buthelezi in 1974, that enshrined the principles of peaceful negotiated transition of power and equality for all, the first of such agreements by black and white political leaders in South Africa. In 1975 he led a break away from the United Party, due to its lame duck approach to criticism of apartheid and became leader of the new Reform Party that led to the realignment of opposition politics in South Africa. Schwarz was one of the defence attorneys in the infamous Rivonia Trial, defending Jimmy Kantor, who was Nelson Mandela's lawyer until he too was arrested and charged. Through the 1970s and 1980s in Parliament he was amongst the most forthright and effective campaigners against apartheid, who was feared by many National Party ministers.

Helen Zille, a white anti-apartheid activist, exposed a police cover-up regarding the death of Black Consciousness founder Steve Biko as a reporter for the Rand Daily Mail. Zille was active in the Black Sash, an organisation of white women formed in 1955 to oppose the removal of Coloured (mixed-race) voters from the Cape Province voters' roll. Even after that failure, however, it went on assisting blacks with issues such as pass laws, housing and unemployment.

Covert resistance was expressed by banned organisations like the largely white South African Communist Party, whose leader Joe Slovo was also Chief of Staff of the ANC's armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe. Whites also played a significant role in opposing apartheid during the 1980s through the United Democratic Front and End Conscription Campaign. The latter was formed in 1983 to oppose the conscription of white males into the South African military. The ECC's support-base was not particularly large, but the government still saw fit to ban it 1988.

The army played a major role in the government's maintenance of its apartheid policies. It was expanded considerably to fight the resistance, and more money was being spent on increasing its effectiveness. It is estimated that something between R4-billion and R5-billion was spent on defence in the mid-'eighties. Conscription was used to increase the size of the army, with stiff prison sentences imposed for draft evasion or desertion.[72] Only white males were conscripted, but volunteers from other races were also drawn in. The army was used to fight battles on South African borders and in neighbouring states, against the liberation movements and the countries that supported them. During the 1980s, the military was also used to repress township uprisings, which saw support for the ECC increase markedly.

Cultural opposition to apartheid came from internationally known writers like Breyten Breytenbach, André Brink and Alan Paton (who co-founded the Liberal Party of South Africa) and clerics like Beyers Naudé.

Some of the first violent resistance to the system was organised by the African Resistance Movement (ARM) who were responsible for setting off bombs at power stations and notably the Park Station bomb. The membership of this group was virtually all drawn from the marginalised white intellectual scene. Founded in the 1960s, many of ARM's members had been part of the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS). Unlike pro-peace opposition NUSAS, however, ARM was a radical organisation. Its backing came mostly from Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth and Cape Town. By 1964, though, ARM ceased to exist, most of its members having been arrested or fled the country.

On 24 July 1964, Frederick John Harris, an associate of ARM, deposited a time bomb in the Johannesburg station. One person was slain, and 22 were injured. Harris explained that he had wanted to show that ARM was still in existence, but both ARM and the ANC slammed his actions. He was sentenced to death and executed in 1965.

Jewish resistance

Many Jewish South Africans, both individuals and organisations, helped support the anti-apartheid movement. It was estimated that Jews were disproportionately represented (some sources maintain by as much as 2,500%) among whites involved in anti-apartheid political activities.[73] Much like other English-speaking white South Africans, Jews supported either the Progressive Party or the United Party. One organisation, the Union of Jewish Women, sought to alleviate the suffering of blacks through charitable projects and self-help schemes. Fourteen of the 23 whites involved in the 1956 Treason Trial were Jewish and all five whites of the 17 members of the African National Congress who were arrested for anti-apartheid activities in 1963 were Jewish.

Some Jewish university students vehemently opposed the apartheid movement. A large number of Jews were also involved in organisations such as the Springbok Legion, the Torch Commando, and the Black Sash. These anti-apartheid organisations led protests that were both active (i.e. marching through the streets with torches) and passive (i.e. standing silently in black). Two Jewish organisations were formed in 1985: Jews for Justice (in Cape Town) and Jews for Social Justice (in Johannesburg) tried to reform South African society and build bridges between the white and black communities. Also in 1985, the South African Jewish Board passed a resolution rejecting apartheid.[74]

In addition to the well-known high profile Jewish anti-apartheid personalities, there were very many ordinary Jews who expressed their revulsion of apartheid in diverse ways and contributed to its eventual downfall. Many Jews were active in providing humanitarian assistance for black communities. Johannesburg's Oxford Synagogue and Cape Town's Temple Israel established nurseries, medical clinics and adult education programs in the townships and provided legal aid for victims of apartheid laws. Many Jewish lawyers acted as nominees for non-whites who were not allowed to buy properties in white areas.[75]

In 1980, South Africa's National Congress of the Jewish Board of Deputies passed a resolution urging "all concerned [people] and, in particular, members of our community to cooperate in securing the immediate amelioration and ultimate removal of all unjust discriminatory laws and practices based on race, creed, or colour." This inspired some Jews to intensify their anti-apartheid activism, but the bulk of the community either emigrated or avoided public conflict with the National Party government.[76]

Indian resistance

Hilda Kuper, writing in 1960, observed of the Natal Indian Congress:

Congress considers that in South Africa the first objective is the removal of discrimination based on race, and is prepared to co-operate with people of all groups who share this ideological outlook.

— Hilda Kuper, Indian People in Natal. Natal: University Press. 1960. p. 53. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016.

Fatima Meer was notable among South African anti-apartheid activists from the Indian diaspora.[77][78]

Role of women

South African women greatly participated in the anti-apartheid and liberation movements that took hold of South Africa. These female activists were rarely at the head of the main organisations, at least at the beginning of the movement, but were nonetheless prime actors. One of the earliest organisation was The Bantu Women's League founded in 1913.[79] In the 1930s and 1940s, female activists were strongly present in trade union movements, which also served as a vehicle for future organisation. In the 1950s, organisations specifically for women were created such as the ANC Women's League (ANCWL) or the Women's Council within the South West Africa People's Organization (SWAPO).[80] In April 1954, the more global Federation of South African Women (FSAW or FedSAW) was founded with the objective to fight against racism and oppression of women as well as to make African women understand that they had rights both as human beings and as women. While female activists fought along men and participated to demonstrations and guerrilla movements, FSAW and ANCWL also acted independently and organised bus boycotts, campaigns against restrictive passes in 1956 in Pretoria and in Sharpeville in 1960.[81] 20,000 women attended these kind of demonstrations. Many participants were arrested, forced into exile or imprisoned, including such as Lilian Ngoyi. In 1958, 2000 women were arrested during an anti-pass campaign.[82] After the Sharpeville massacre, however, many organisations such as FSAW were banned and went underground.

At the same time South African women fought against gender discrimination and called for rights specific to women, such as family, children, gender equality and access to education. At a conference in Johannesburg in 1954, the Federation of South African Women adopted the "Women's Charter",[83] which focused on rights specific to women both as women and mothers. The Charter referred both to human rights, women's rights and asked for universal equality and national liberation. In 1955, in a document drafted in preparation for the Congress of People,[84] the FSAW made more demands, including free education for children, proper housing facilities and good working conditions, such as the abolition of child labour and a minimum wage.

The difficulty for these local movements was to raise global awareness to truly have an impact. Yet, their actions and demands gradually attracted the attention of the United Nations and put pressure on the international community. In 1954, Lilian Ngoyi attended the World Congress of Women in Lausanne, Switzerland.[85] Later, in 1975, the ANC was present at the 1975 United Nations Decade for Women in Copenhagen and in 1980 an essay on the role of women in the liberation movement[86] was prepared for the United Nations World Conference. This has been crucial in the recognition of Southern African women and their role in the anti-apartheid movement.

Among important activists during the anti-apartheid movement were Ida Mntwana, Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph, and Dorothy Nyembe.[87] Lilian Ngoyi joined the ANC National Executive and was elected first vice-president and later president of FSAW in 1959. Many of these leaders served long prison sentences.

See also

Notes and references

Annotations

- The ANC made its decision to begin passive resistance against the apartheid system on 17 December 1950. The first significant organised protests against apartheid did not occur until the Defiance Campaign in 1952.[1]

References

- "The Defiance Campaign". South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid Building Democracy. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- du Toit, Pierre (2001). South Africa's Brittle Peace: The Problem of Post-Settlement Violence. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 90–94. ISBN 978-0333779187.

- Powell, Jonathan (2015). Terrorists at the Table: Why Negotiating is the Only Way to Peace. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-1250069887.

- Thomas, Scott (1995). The Diplomacy of Liberation: The Foreign Relations of the ANC Since 1960. London: Tauris Academic Studies. pp. 202–210. ISBN 978-1850439936.

- Ugorji, Basil (2012). From Cultural Justice to Inter-Ethnic Mediation: A Reflection on the Possibility of Ethno-Religious Mediation in Africa. Denver: Outskirts Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-1432788353.

- Tom Lodge, "Action against Apartheid in South Africa, 1983–94", in Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds), Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 213–30. ISBN 978-0-19-955201-6.

- Ottoway, Marina (1993). South Africa: The Struggle for a New Order. Washington: Brookings Institution Press. pp. 23–26. ISBN 978-0815767152.

- Lodge, Tim (2011). Sharpeville: An Apartheid Massacre and Its Consequences. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 31–34. ISBN 978-0192801852.

- Morton, Stephen (2013). States of Emergency: Colonialism, Literature and Law. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-1846318498.

- Jacklyn Cock, Laurie Nathan (1989). War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa. New Africa Books. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-0-86486-115-3.

- Ottoway, Marina (1993). South Africa: The Struggle for a New Order. Washington: Brookings Institution Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-0815767152.

- Minter, William (1994). Apartheid's Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. pp. 114–117. ISBN 978-1439216187.

- Mitchell, Thomas (2008). Native vs Settler: Ethnic Conflict in Israel/Palestine, Northern Ireland and South Africa. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 194–196. ISBN 978-0313313578.

- Pandey, Satish Chandra (2006). International Terrorism and the Contemporary World. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, Publishers. pp. 197–199. ISBN 978-8176256384.

- Myre, Greg (18 June 1991). "South Africa ends racial classifications". Southeast Missourian. Cape Girardeau. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- "A brief history of the African National Congress" Archived 5 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, ANC.

- Valdi, Ismail (16 January 2012). "Historical Overview of Black Resistance, 1932-1952 - The Congress of the People and Freedom Charter Campaign by Ismail Vadi, New Delhi, 1995 | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Naicker, M.P (21 June 2019). "The defiance campaign by M. P. Naicker | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Clark, Nancy L, Worger, William H. (2011). South Africa : the rise and fall of apartheid (PDF). Worger, William H. (2nd ed.). Harlow, England: Longman. pp. 141–143. ISBN 978-1-4082-4564-4. OCLC 689549065.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lal, Vinay (2014). "Mandela, Luthuli, and Nonviolence in the South African Freedom Struggle". Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies. 38 (1): 36–54. ISSN 0041-5715 – via escholarship.

- "Apartheid Legislation 1850s-1970s | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 21 March 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "1953. Criminal Law Amendment Act No 8 - The O'Malley Archives". omalley.nelsonmandela.org. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Defiance Campaign 1952 | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 21 March 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Nelson Mandela Timeline 1950-1959 | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "United Nations and Apartheid Timeline 1946-1994 | South African History Online". sahistory.org.za. 21 March 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Vahed, Goolam (2013). ""Gagged and trussed rather securely by the law": The 1952 Defiance Campaign in Natal". Journal of Natal and Zulu History. 31 (2): 68–89. doi:10.1080/02590123.2013.11964196. ISSN 0259-0123 – via tandfonline.

- Davenport, T. R. H., (2000). South Africa : a modern history. Saunders, Christopher C.,, Palgrave Connect (Online service) (5th ed.). Hampshire [England]: Macmillan Press. pp. 403–405. ISBN 978-0-230-28754-9. OCLC 681923614.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Meredith, Martin. (2010). Mandela : a Biography (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. pp. 129–130. ISBN 1-282-56267-3. OCLC 647906301.

- Roberts, Benjamin (26 June 2020). "South Africa's Freedom Charter campaign holds lessons for a fairer society". www.iol.co.za. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Congress of the People and the Freedom Charter | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 21 March 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- McKinley, Dale. (2015). 60 Years of the freedom charter : no cause to celebrate for the working class. Jansen, Martin,, Thompson, Lynn., Ward, Donovan., Shapiro Jonathan., Mayibuye centre. Cape Town: Workers’ World Media Productions. pp. II-4. ISBN 978-0-620-65513-2. OCLC 919436893.

- Levy, Norman (18 June 2015). "The Freedom Charter by Norman Levy | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 31 March 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "The 1956 Women's March in Pretoria | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 13 May 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "What Happened at the Treason Trial? - Africa Media Online". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- David M. Sibeko (March 1976). "The Sharpeville Massacre: Its historic significance in the struggle against apartheid". United Nations Centre against Apartheid. Archived from the original on 8 April 2005. Retrieved 20 August 2005.

- Wheatley, Stephen (4 April 2020). "How the Sharpeville massacre changed the course of human rights". The Independent. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "Sharpeville Massacre, 21 March 1960 | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 31 March 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "The Sharpeville Massacre". CMHR. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Staff, Guardian (22 March 1960). "Police Fire Kills 63 Africans". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Stapleton, Timothy (2010). A Military History of South Africa: From the Dutch-Khoi Wars to the End of Apartheid. Santa Barbara: Praeger Security International. pp. 159–169. ISBN 978-0313365898.

- Louw, P. Eric (1997). The Rise, Fall, and Legacy of Apartheid. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. pp. 121–124. ISBN 0-275-98311-0.

- "Percy John "Jack" Hodgson | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Magubane, Bernard; Bonner, Philip; Sithole, Jabulane; Delius, Peter; Cherry, Janet; GIbbs, Patt; April, Thozama (2010). "The turn to armed struggle" (PDF). In South African Democracy Education Trust. (ed.). The road to democracy in South Africa (1st ed.). Cape Town: Zebra Press. pp. 136–142. ISBN 978-1-86888-501-5. OCLC 55800334.

- Stevens, Simon (1 November 2019). "The Turn to Sabotage by The Congress Movement in South Africa". Past & Present. 245 (1): 221–255. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtz030. ISSN 0031-2746.

- Baines, Gary (2014). South Africa's 'Border War': Contested Narratives and Conflicting Memories. London: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 142–146. ISBN 978-1472509710.

- "uMkhoto weSizwe (MK) launches its first acts of sabotage". South African History Online. 15 December 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Macdonald, Nancy; Findlay, Stephanie (12 December 2013). "Nelson Mandela conquered apartheid, united his country and inspired the world - Macleans.ca". www.macleans.ca. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Police arrest members of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) High Command at Lilliesleaf Farm | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 16 March 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Okoth, Assa. (2006). A history of Africa. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers. p. 181. ISBN 978-9966-25-357-6. OCLC 71210556.

- "Robert Sobukwe | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Lissoni, Arianna (1 June 2009). "Transformations in the ANC External Mission and Umkhonto we Sizwe, c. 1960–1969". Journal of Southern African Studies. 35 (2): 287–301. doi:10.1080/03057070902919850. ISSN 0305-7070.

- "Pan Africanist Congress timeline 1959-2011 | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 7 September 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Pan Africanist Congress timeline 1959-2011 | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 7 September 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Mataboge, Mmanaledi (19 March 2010). "Almost a revolution". The Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Leeman, Bernard (1996). "THE PAN AFRICANIST CONGRESS OF AZANIA". In Alexander, Peter F; Hutchison, Ruth; Schreuder, Deryck (eds.). Africa today : a multi-disciplinary snapshot of the continent in 1995. Canberra: Goanna Press. pp. 172–192. ISBN 0-7315-2491-8. OCLC 38410420.

- "Rivonia Trial 1963 - 1964 | South African History Online". www.sahistory.org.za. 13 March 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Anti-apartheid icon reconciled a nation". Los Angeles Times. 5 December 2013. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs (7 January 2008). "The End of Apartheid". 2001-2009.state.gov. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Callinicos, Luli (1 September 2012). "Oliver Tambo and the Dilemma of the Camp Mutinies in Angola in the Eighties". South African Historical Journal. 64 (3): 587–621. doi:10.1080/02582473.2012.675813. ISSN 0258-2473.

- "ANC Submission to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission". www.justice.gov.za. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Adeleke, Tunde (16 April 2008). "African National Congress (ANC) •". Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Clark, Worger & 2011, p. 63-72.

- Slightly more contentious was the movement's decision to stop working with white liberals in multi-racial organisations.

- 16 June 1976 Student Uprising in Soweto. africanhistory.about.com

- Harrison, David (1987). The White Tribe of Africa.

- Eades, Lindsay Michie 1962- (1999). The end of apartheid in South Africa. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29938-2. OCLC 246092999.

- "The Anti-Apartheid Struggle in South Africa (1912-1992)". ICNC. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- "The Anti-Apartheid Struggle in South Africa (1912-1992)". ICNC. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- "Tutu, Other Clergy Arrested in Protest", The Harvard Crimson, 1 March 1988.

- New York Times (archives), "Catholic Defiance of Apartheid Is Stirring South Africa," John Burns, Feb. 6, 1977.

- John D. Battersby (28 March 1988). "More Whites in South Africa Resisting the Draft". New York Times.

- "Legendary Heroes of Africa - Stamps to Commemorate Jewish anti Apartheid South African Liberation struggle". Legendary Heroes of Africa. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011.

- Jewish opposition to the Apartheid Regime

- "South African Jews Against Apartheid". Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 April 2005. Retrieved 6 July 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The Jews of Africa

- Pillay, Taschica (12 March 2010). "Fatima Meer dies". TIMES Live. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- "60 Iconic Women — The people behind the 1956 Women's March to Pretoria (11-20)". Mail & Guardian. 25 August 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Bernstein, Hilda. For their Triumphs and for their Tears: Women in Apartheid South Africa(International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa. Revised and enlarged edition, London, March 1985), p. 86.

- Lachick and Urdang, p. 110.

- Rob Davies, Dan O'Meara and Sipho Dlamini, The Struggle For South Africa: A Reference Guide to Movements, Organizations and Institutions. Volume Two (London: Zed Books, 1984), p. 366.

- Bernstein, p. 96.

- ANC/FSAW, Women's Charter. Archived 28 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ANC/FSAW, What Women Want Archived 2 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Compiled in Preparation for the Congress of the People, 1955.

- ANC official website, Lilian Nogyi Archived 16 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ANC, Secretariat for the World Conference of the United Nations Decade for Women. The Role of Women in the Struggle Against Apartheid, 1980. Archived 22 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Bernstein, pp. 100–101.