Tikopia

Tikopia is a high island in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It is part of the Solomon Islands of Melanesia, but is culturally Polynesian. The first Europeans arrived on 22 April 1606 as part of the Spanish expedition of Pedro Fernandes de Queirós.[1]

NASA picture of Tikopia | |

Tikopia | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 12°17′47.3″S 168°49′55.0″E |

| Archipelago | Solomon Islands |

| Area | 5 km2 (1.9 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 380 m (1,250 ft) |

| Highest point | Reani |

| Administration | |

| Province | Temotu |

| Demographics | |

| Ethnic groups | Polynesian |

Location and geography

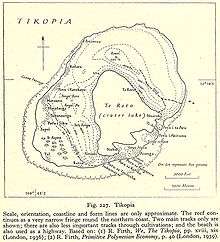

Covering an area of 5 square kilometres (1.9 square miles), the island is the remnant of an extinct volcano. Its highest point, Mt. Reani, reaches an elevation of 380 metres (1,250 feet) above sea level. Lake Te Roto covers an old volcanic crater which is 80 metres (260 feet) deep.[2]

Tikopia's location is relatively remote. It is sometimes grouped with the Santa Cruz Islands. Administratively, Tikopia belongs to Temotu Province as the southernmost of the Solomon Islands. Some discussions of Tikopian society include its nearest neighbour, the even tinier island of Anuta.

History as a Polynesian outlier

While it is located in Melanesia, the people of Tikopia are culturally Polynesian. Their language, Tikopian, is a member of the Samoic branch of the Polynesian languages. The linguistic analysis indicates that Tikopia was colonized by seafaring Polynesians, mostly from the Ellice Islands (Tuvalu).

The time frame of the migration is not precisely identified but is understood to be some time between the 10th century to the mid-13th century.[3] The arrival of the voyagers in Anuta could have occurred later. The pattern of settlement that is believed to have occurred is that the Polynesians spread out from Tonga and other islands in the central and south eastern Pacific. During pre-European-contact times there was frequent canoe voyaging between the islands as Polynesian navigation skills are recognised to have allowed deliberate journeys on double-hull sailing canoes or outrigger canoes.[4] The voyagers moved into the Tuvaluan atolls as a stepping stone to migration into the Polynesian outlier communities in Melanesia and Micronesia.[5][6][7]

In Tikopian mythology Atua Fafine and Atua I Raropuka are creator gods and Atua I Kafika is the supreme sky god.

Population

The population of Tikopia is about 1,200, distributed among more than 20 villages mostly along the coast. The largest village is Matautu on the west coast[2] (not to be confused with Mata-Utu, the capital of Wallis and Futuna). Historically, the tiny island has supported a high-density population of a thousand or so. Strict social controls over reproduction prevented further increase.[8][9]

Tikopians practice an intensive system of agriculture (which has been compared to permaculture), similar in principle to forest gardening and the gardens of the New Guinea Highlands. Their agricultural practices are strongly and consciously tied to the population density.[2] For example, around 1600, the people agreed to slaughter all pigs on the island, and substitute fishing, because the pigs were taking too much food that could be eaten by people.[2] Tikopians have developed rituals and figurative constructions related to their fishing practices.[10]

Unlike the rapidly Westernizing society of much of the rest of Temotu Province, Tikopia society is little changed from ancient times. Its people take great pride in their customs, and see themselves as holding fast to their Polynesian traditions while they regard the Melanesians around them to have lost most of theirs.[11] The island is controlled by four chiefs (ariki) Kafika, Tafua, Taumako and Fangarere, with Kafika recognised as the first among equals.[12]

Tikopians have a highly developed culture with a strong Polynesian influence, including a complex social structure.[2]

Field work on Tikopia by Raymond Firth

New Zealand anthropologist Raymond Firth, who lived on Tikopia in 1928 and 1929, detailed its social life. He showed how the society was divided geographically into two zones and was organized into four clans, headed by clan chiefs.[2] At the core of social life was te paito – the house inherited from male (patrilineal) ancestors, who were buried inside it. Relationships with the family grouping of one's mother (matrilateral relations) were also very important. The relations between a mother's brother and his nephew had a sacred dimension: the uncle oversaw the passage of his nephew through life, in particular, officiating at his manhood ceremonies. Intricate economic and ritual links between paito houses and deference to the chiefs within the clan organization were key dimensions of island life.

Raymond Firth, who did his post-graduate anthropological study under Bronislaw Malinowski in 1924, speculates about the ways population control may have been achieved, including celibacy, warfare (including expulsion), infanticide and sea-voyaging (which claimed many youths). Firth's book, Tikopia Ritual and Belief (1967, London, George Allen & Unwin) remains an important source for the study of Tikopia culture.

Christianity

The Anglican Melanesian Mission first made contact with Tikopia in 1858. A mission teacher was not allowed to settle on the island until 1907.[2][11] Conversion to Christianity of the total population did not occur until the 1950s.[11] Tikopia is part of Anglican Church of Melanesia.

The introduction of Christianity resulted to the banning of traditional birth control,[8] which had the consequence of a 50% increase of the population: 1,200 in 1920 to 1,800 in 1950. The increase in population resulted in migration to other places in the Solomon Islands, including in the settlement of Nukukaisi in Makira.[8]

Shipwreck

On Tikopia in 1964, explorers found artefacts from the shipwreck of the expedition of Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse.

Cyclone Zoe

Cyclone Zoe in December 2002 devastated the vegetation and human settlements in Tikopia.[13][14] Despite the extensive damage, no deaths were reported, as the islanders followed their traditions and sheltered in the caves in the higher ground. The narrow bank that separated the freshwater lagoon from the sea was breached by the storm, resulting in the continuing contamination of the lagoon and the threatened death of the sago palms on which the islanders depend for survival.[14] A remarkable international effort by "friends of" the island, including many yacht crews who had had contact with Tikopia over the decades, culminated in the construction in 2006 of a gabion dam to seal the breach.[14]

Cultural significance

Jared Diamond's book Collapse describes Tikopia as a success case in matching the challenges of sustainability, contrasting it with Easter Island.

Tikopia in media

In 2009 a double canoe closely following the original design of the traditional Tikopia canoes was donated to the island, as well as to Tikopia's sister island Anuta, in order to give the islands their own independent sea transport. This canoe called 'Lapita Tikopia' and its sistership 'Lapita Anuta' were built in the Philippines in 2008 and sailed to Tikopia and Anuta in a 5 months voyage following the ancient migration route of the Lapita people into the Pacific. This voyage was called the 'Lapita Voyage', with more information about the voyage here. Its original concept (by Hanneke Boon of James Wharram Designs) to donate such a canoe was first published in 2005 in a project called 'A Voyaging Canoe for Tikopia' in order to raise money for the building of the canoes. The project was filmed and is available as DVD.

In 2013 a Norwegian mother and father brought their two children and a nephew to Tikopia and lived there for 6 months. A film crew went along and a 13 episode children's series was made of the family experiences and stay, primarily focusing on the experiences of the young daughter of the Norwegian family, Ivi, with the local children, local school the local chief Tafua and his family, etc. The series was shown on NRK television channel NRK Super.[15]

In October 2018, the king of the island, Ti Namo, made his first visit to the western world to share his worries about climate change on his island. He went to Grenoble in France, where he presented his documentary Nous Tikopia before a national release on November 7, and declared to the press, "Before, we suffered a cyclone every ten years. Today it's every two years."[16]

See also

- Oceania

- Pacific Islands

References

- Kelly, Celsus, O.F.M. La Austrialia del Espiritu Santo. The Journal of Fray Martín de Munilla O.F.M. and other documents relating to the Voyage of Pedro Fernández de Quirós to the South Sea (1605-1606) and the Franciscan Missionary Plan (1617-1627) Cambridge, 1966, p.39, 62.

- "Tikopia". Solomon Islands Historical Encyclopaedia 1893-1978. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Kennedy, Donald G. (1929). "Field Notes on the Culture of Vaitupu, Ellice Islands". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 38: 2–5.

- Bellwood, Peter (1987). The Polynesians – Prehistory of an Island People. Thames and Hudson. pp. 39–44.

- Bellwood, Peter (1987). The Polynesians – Prehistory of an Island People. Thames and Hudson. pp. 29, 54. ISBN 978-0500274507.

- Bayard, D.T. (1976). The Cultural Relationships of the Polynesian Outiers. Otago University, Studies in Prehistoric Anthropology, Vol. 9.

- Kirch, P.V. (1984). "The Polynesian Outiers". Journal of Pacific History. 95 (4): 224–238. doi:10.1080/00223348408572496.

- Macdonald, Judith (1991). Women of Tikopia (Thesis). Thesis (PhD - Anthropology) University of Auckland.

- Resture, Jane. "Tikopia". Solomon Islands. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Firth, Raymond (1981). "Figuration and symbolism in Tikopia fishing and fish use". Journal de la Société des Océanistes. 37 (72): 219–226. doi:10.3406/jso.1981.3062.

- Macdonald, Judith (2000). "Chapter 6, Tikopia and "What Raymond Said"" (PDF). Ethnographic Artifacts: Challenges to a Reflexive Anthropology. University of Hawaii Press: edited by S. R. Jaarsma, Marta Rohatynskyj. pp. 112–13.

- Macdonald, Judith (2003). "Tikopia". Volume 2, Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures. edited by Carol R. Ember, Melvin Ember, Springer. pp. 885–892. doi:10.1007/0-387-29907-6_92. ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6.

- "Tikopia project". help save a civilization. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Baldwin, James. "Excerpt from the book 'Across Islands and Oceans'". Tikopia Island: A little-known outpost of traditional culture in the South Pacific. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- "NRK Super TV - Flaskepost fra Stillehavet". tv.nrksuper.no. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Le roi de Tikopia en visite à Grenoble". francebleu.fr (in French). 28 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

External links

- (The Island of Tikopia. HTV International/Channel 4 UK 1984) Early documentary film for UK television by Krov and Ann Menuhin. Part of the series of South Seas Voyage. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7QEPkMa3avA

- Flaskepost fra stillehavet (Message in a Bottle from the Pacific Ocean) A children's television program produced by NRK about a Norwegian family that spends a year living on the Island.

- An essay on Tikopia, prepared for the BBC

- BBC photo essay, from the aftermath of Cyclone Zoe Despite the overwhelming devastation and the greatest fears, no one on Tikopia was killed in the disaster.

- Tools and practical help after the cyclone

- Restoring the freshwater lagoon of Tikopia

- Solomon Islands - John Seach a Tour Site but with information on each of the islands

- older detail map

- A Voyaging Canoe for Tikopia

- Lapita Voyage official website

- Lapita voyage, introduction and blogs

Further reading

- Baldwin, James, Across Islands and Oceans, specially chapter 8. Tikopia Unspoilt (Amazon Kindle Book)

- Firth, Raymond (2004), We the Tikopia (reprint ed.), London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-33020-6, retrieved 18 November 2012First published 1936 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd. This classic study is still used in contemporary anthropology classes

- Firth, Raymond, The Work of the Gods in Tikopia, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press (1940, 1967)

- Firth, Raymond, SOCIAL CHANGE IN TIKOPIA. Re-Study of a Polynesian Community after a Generation, London: Allen and Unwin. 1959, 360 pages

- Firth, Raymond (2006). Tikopia Songs: Poetic and Musical Art of a Polynesian People of the Solomon Islands. Cambridge University Press.

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton; C. Christensen (1981), Nonmarine mollusks from archaeological sites on Tikopia, southeastern Solomon Island, S. Pacific Science 35:75-88

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton; Yen, D.E (1982), Tikopia; The Prehistory and Ecology of a Polynesian Outlier, Honolulu, Hawaii: Bishop Museum Press, ISBN 9780910240307

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (1983), Mangaasi-style ceramics from Tikopia and Vanikoro and their implications for east Melanesian prehistory, Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association Bulletin 3:67-76

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (1986), Tikopia: tracing the prehistory of a Polynesian culture, Archaeology 39(2):53-59

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (1986), Exchange systems and inter-island contact in the transformation of an island society: The Tikopia case, P. V. Kirch, ed., Island Societies: Archaeological Approaches to Evolution and Transformation, pp. 33-41. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton; D. Steadman and D. S. Pahlavan (1990), Extinction, biogeography, and human exploitation of birds on Anuta and Tikopia, Solomon Islands, Honolulu, Hawaii: Occasional Papers of the Bishop Museum 30:118-153

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (1996), Tikopia social space revisited, J. Davidson, G. Irwin, F. Leach, A. Pawley, and D. Brown, eds., Oceanic Culture History: Essays in Honour of Roger Green, pp. 257-274. Dunedin: New Zealand Journal of Archaeology Special Publication

- Macdonald, Judith (1991). Women of Tikopia (Thesis). Thesis (PhD - Anthropology) University of Auckland.

- Macdonald, Judith (2000). "Chapter 6, Tikopia and "what Raymond Said"" (PDF). Ethnographic Artifacts: Challenges to a Reflexive Anthropology. University of Hawaii Press: edited by S. R. Jaarsma, Marta Rohatynskyj.

- Macdonald, Judith (2003). "Tikopia". Volume 2, Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures. Springer: edited by Carol R. Ember, Melvin Ember. pp. 885–892. doi:10.1007/0-387-29907-6_92. ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6.