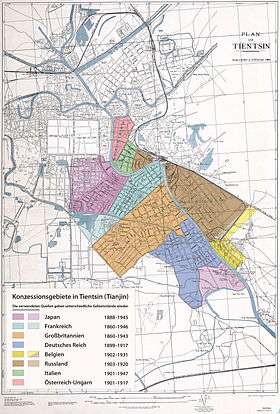

Concessions in Tianjin

The concessions in Tianjin (formerly romanized as Tientsin) were concession territories ceded by the Chinese Qing dynasty to a number of European countries, the U.S. and Japan within the city of Tianjin. There were nine concessions in old Tianjin altogether. These concessions also contributed to the rapid development of Tianjin from the early to mid-20th century. The first concessions in Tianjin were granted in 1860. By 1943, all the foreign concessions, save the Japanese concession, had ceased to exist de facto.

General context

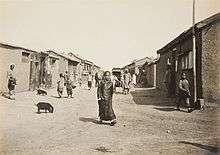

Prior to the 19th century, the Chinese were concerned that European trade and missionary activity would upset the order of the empire. Strictly controlled and subject to import tariffs, European traders were limited to operating in Canton and Macao. Following a series of military defeats against Britain and France, the Qing were slowly forced to permit extraterritoriality for foreign nationals and even cessions of Chinese sovereignty over certain ports and mineral rights.

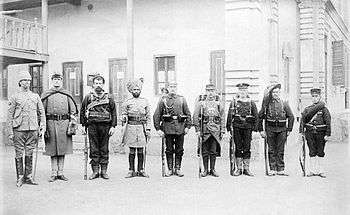

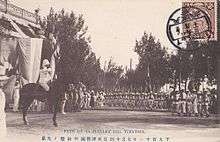

Tianjin's position at the intersection of the Grand Canal and the Peiho River connecting Beijing to the Bohai Bay made it one of the premier ports of northern China. Foreign trade was approved there for the British and French by the 1860 Peking Convention. Its importance increased even further when it was connected to the Tangshan coal fields by the Kaiping Tramway, the railroad that eventually connected all of northern China and Manchuria. Between 1895 and 1900, the two original powers were joined by Japan, Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, Italy and Belgium – countries without concessions elsewhere in China – in establishing self-contained concessions each with their own prisons, schools, barracks and hospitals. The European settlements covered 5 square miles (13 km2) in all, the riverfront being governed by foreign powers.[1] After decades, the Japanese, French, and British concessions (which were situated on the right bank of the Peiho River)[1] became the most prosperous ones.

With the overthrow of the Chinese Qing dynasty, the new Republic of China managed a restructuring of Chinese domestic and foreign relations, allowing it to recognize European states as equals. In turn, the concessions in Tianjin were dismantled in the early to mid-20th century with successful recognition of the European states of the Republic of China, which gave European property owners equality before Chinese officials. However, World War II disrupted this nascent development: the Japanese seized the concessions of powers allied against it during its occupation of the country. Soon after the war, all foreign powers relinquished their concessions in China, including in Tianjin.

Austro-Hungarian concession (1901–1917)

Austria-Hungary participated in the Eight-Nation Alliance that suppressed the Boxer rebellion (1899–1901). Austria-Hungary together with Italy sent the smallest force of the Eight-Nation Alliance. Four cruisers and 296 Hungarian enlisted soldiers were dispatched.[2]

On December 27, 1902, Austria-Hungary gained a concession zone in Tianjin as part of the reward for its contribution to the Alliance. The Austro-Hungarian concession zone was 150 acres (0.61 km2) in area, situated next to the Pei-Ho river and outlined by the Imperial channel and the Tianjin-Peking railway track. Its population was around 30,000 people. Order was maintained by 40 Austro-Hungarian marines and 70 Chinese militia (Shimbo).

The self-contained concession had its own thermae, theatre, pawnshop, school, barracks, prison, cemetery and hospital. It also contained the Austro-Hungarian consulate and its citizens were under Austro-Hungarian, not Chinese rule. Despite its relatively short life-span, the Austrians left their mark on the area, as can be seen in the Austrian architecture in the city.

The administration was done by a town council composed of local high-class noblemen and headed by the Austro-Hungarian consul and the military commander, the two of them had a majority vote. The focus of the juridical system was on smaller crimes and it was based on Austro-Hungarian law. If a Chinese person committed a crime on Chinese soil he could be tried in their own courts.[3]

Austria-Hungary was, due to World War I, unable to maintain control of its concession. The concession zone was swiftly occupied by China at the Chinese declaration of war on the Central powers and on 14 August 1917 the lease was terminated, along with that of the larger German concession in the same city.[4] Austria finally abandoned all claim to it on September 10, 1919 (Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye), Hungary made a similar recognition on June 4, 1920 (Treaty of Trianon). The former Austro-Hungarian concession renamed the "Second Special District", was placed under the permanent administration of the Chinese government.[note 1]

Belgian concession (1902–1931)

The Belgian Concession was established in 1902 after Belgian envoy Maurice Joostens claimed the parcel in the negotiations following the defeat of the Boxer rebels. Located on the eastern bank of the Hai River (Hai He), the Belgian government and business community did not invest in development of the concession. The concession was nominal and of little value and an agreement to return the concession to China was signed in August 1929 and approved by the Belgian parliament in 1931.[5]

Much more important were contracts involving railways, electric power systems and tramways built and partly operated by Belgian private companies. In 1904, China and Belgium signed a contract with the Compagnie de tramways et d'éclairage de Tientsin, giving the company an official monopoly for 50 years over trams and electric lighting in the city. In 1906, with the opening of the first route of the tramway system, Tianjin became the first Chinese city to have a modern public transportation system (Shanghai had to wait until 1908 to get electric tramways). The supply of electricity and lighting and the trolley business were profitable ventures. By 1914, the network covered the Chinese city as well as the Austrian, French, Italian, Japanese and Russian concessions.

The Compagnie de tramways et d'éclairage de Tientsin was taken over by the Japanese army in 1943 and the members of the Belgian staff, often with their families, were sent to internment camps. Following the end of World War II, the Chinese authorities took over the network. The Brussels-based company tried to get compensation, but the Chinese Revolution in 1949 left them without any indemnity. Two more lines were built under Chinese administration, but the network was finally closed around 1972.

British concession (1860–1943)

The British concession, which contained the trade and financial centres, was situated on the right bank of the river Haihe below the native city, occupying some 200 acres (0.81 km2). It was held on a lease in perpetuity granted by the Chinese government to the British Crown, which sublet plots to private owners in the same way as was done at Hankou.[1]

The local management was entrusted to a municipal council organized on lines similar to those in Shanghai.[1] The seat of government was the stately Gordon Hall, situated on the financial street called Victoria Road (now Jiefang Lu).

The British concession was blockaded by the Japanese during the Tientsin incident in June 1939, causing a major diplomatic crisis.

The Japanese occupied the British concession upon their declaration of war against Britain on 7 December 1941 until the end of the war.

The British concession in Tianjin was formally returned to China with the Sino-British Treaty for the Relinquishment of Extra-Territorial Rights in China, ratified on 20 May 1943, although the Chinese could not take possession until the end of the war ended the Japanese occupation.

French concession (1860–1946)

The French concession was established in 1860. After more than 100 years, almost every prominent building in the original concession is still extant, including the French Consulate, the Municipal Council, the French Club, the Catholic Cathedral, the French Garden and many others. Many of the bank buildings along the financial street (currently Jiefang Lu, formerly the Rue de France) are still in existence today.

The villas around the Garden Road are beautiful and diverse. Many French celebrities lived in Tianjin. Among them, Paul Claudel (consul 1906 - 1909), and the natural scientist Father Emile Licent who conducted research in Tianjin from 1914 to 1939. He founded the Musee Hoang-Ho Pai-Ho (Museum of Yellow River and Peiho River) and left it 20,000 specimens of animals, plants and fossils, as well as 15,000 books. In 1998, the Tianjin government rebuilt the Tianjin Nature Museum.

The dome of the French Cathedral was damaged during the Cultural Revolution: some young Red Guards climbed to the top of the dome to destroy the cross, though later the Tianjin government not only repaired the cross but also renovated the entire church.

German concession (1899–1917)

By the late 1870s, the German Empire was on a course of extensive economic involvement in several Chinese provinces, among them the Tianjin area. The German enclave south of the Hai River was situated between the British and one of the Japanese concessions. In July 1877 xenophobic groups threatened the life and property of German merchants in Tianjin. Local unrest intensified, mainly due to poor harvests and resulting famine, and Tianjin business interests requested armed protection. The German admiralty then dispatched the corvette SMS Luise to China. This initial show of support eventually evolved into a permanent presence in Chinese waters by initially modest German naval forces.

After Germany acquired the Kiautschou Bay region in 1898 with a 99-year lease, a further concession was negotiated for the Tianjin enclave and economic growth escalated with infrastructure improvements. Major trading houses and diverse enterprises established themselves, including a branch of the Deutsch-Asiatische Bank. The Boxer rebellion of 1900 initially laid siege to the foreign concessions in Tianjin, but the city was secured and used as a staging area for the eventual march on Peking by the eight-nation international relief forces.

China swiftly occupied the German concession after it declared war on the Central Powers in August 1917. In 1919, the former concession, renamed the "First Special District", was placed under the permanent administration of the Chinese government. The United States 15th Infantry was billeted in the former German barracks from 1917 until 1938, departing only after the Imperial Japanese Army entered Tianjin.

Italian concession (1901–1943)

On September 7, 1901, Italy was granted a concession in Tianjin from the Chinese government. On June 7, 1902, the Italians took control of the concession, which was to be administered by an Italian consul. It became the headquarters[6] of the Italian Legione Redenta (an "Italian legio" made of irredentist troops in the defeated Austro-Hungarian empire), that fought in 1919 against Lenin's Soviet troops in Siberia and Manchuria.[7]

When Tianjin became in danger of being stormed by warring factions during the civil war of 1927–1928, Italian troops temporarily occupied the Second Special District to protect the city's power station and main railway station. They withdrew after a short while.[8]

In 1935, the Italian Concession had a population of about 6,261, including about 536 foreigners. The Regia Marina (Italian Royal Navy) stationed some vessels in Tianjin. During World War II, the concession had a garrison of approximately 600 Italian troops.

On September 10, 1943, when Italy signed an armistice with the Allies, the concession was occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army. Later in 1943, the Italian Social Republic (RSI) ceded the concession to Wang Jingwei's Japanese-sponsored Chinese puppet state, the Reorganized National Government of China. The Italians were never to regain control over the concession and the Republic of Italy's surrender of all its rights over it by the peace treaty of 1947, was therefore a mere formality.

Japanese concession (1898–1945)

The Japanese concession was initially established in 1898 in the aftermath of the First Sino-Japanese War and additional areas were added in 1900–1902 after the Boxer Rebellion. In 1937, the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) occupied the entire city of Tianjin excluding the foreign concessions. These were occupied in 1941 and in 1943. The Japanese concession ceased to exist with the capitulation of Japan in 1945.

In 1924, the last emperor of the Qing Dynasty, Puyi, was forced to leave the Forbidden City in Beijing and lived in Tianjin until 1931 when he was forcibly taken by the Japanese army to Dalian. The imperial concubine Wenxiu divorced Puyi in Tianjin, which was the first time in Chinese dynastic history that an imperial concubine divorced an emperor.

Russian concession (1900–1920)

A treaty granting a concession to the Russian Empire in Tianjin was signed 31 December 1900. Even before the official treaty was signed, the general in charge of the Russian forces in the city since the Boxer Rebellion had already laid claim to the future concession by right of conquest and Russian troops had already begun placing boundary markers. The concession, on the left bank of the Peiho River, was larger than any of the other foreign concessions, which according to the agreement was due to "Russian trade at Tientsin being on the increase".[9] In reality, Russian economic involvement in Tientsin was insignificant and became even more so after the Russian defeat in the Russo-Japanese War. For this reason, the concession remained largely underdeveloped.

The 398 hectares (3.98 km2) concession was divided into two non-contiguous districts (east and west). In 1920 the Chinese Beiyang government retook the land and concession from the Russian SFSR and in 1924, the Soviet Union renounced its claim on the concession.

American concession (1869–1902)

The United States never requested or received extraterritorial rights in Tianjin, but a de facto concession was administered from 1869 until 1880, principally under the aegis of the British mission. In 1902 this informal American territory became part of the British concession. The United States maintained a permanent garrison at Tianjin, provided from January 1912 until 1938 by the 15th Infantry, US Army, and then by the US Marine Corps until December 8, 1941, the day the United States entered the Second World War and all territories of the US and the British Empire in Asia and the Pacific faced the threat of attack by the Empire of Japan.

Lloyd Horne recalls of his time there in the 1930s "I was detailed with the 15th Infantry to rescue missionaries that were being trapped there. It was like they were prisoners — they couldn't even come out of their billets without getting fired on or having rocks thrown at them."[10]

Annex

Lists of consul-generals

Austro-Hungarian consul-generals

- Carl Bernauer (1901–1908)

- Erwin Ritter von Zach (1908)

- Miloslav Kobr (1908–1912)

- Hugo Schumpeter (1913–1917)[4]

Belgian consul-generals

- Henri Ketels (1902–1906)

- Albert Disière (1906–1914)

- Auguste Dauge (1914–1919)

- Ernest Franck (1919–1923)

- Alphonse van Cutsem (1923–1929)

- Tony Snyers (1929–1931)

British consul-generals

- James Mongan (1860–1877)

- William Hyde Lay (1870, acting)

- Sir Chaloner Grenville Alabaster (1877–1885)

- Byron Brenan (1885–1893)

- Henry Barnes Bristow (1893–1897)

- Benjamin Charles George Scott (1897–1899)

- William Richard Carles (1899–1901)

- Lionel Charles Hopkins (1901–1908)

- Sir Alexander Hosie (1908–1912)

- Sir Henry English Fulford (1912–1917)

- William Pollock Ker (1917–1926)

- James William Jamieson (1926–1930)

- Lancelot Giles (1928–1934)

- John Barr Affleck (1935–1938)

- Edgar George Jamieson (1938–1939)

- Oswald White (1939–1941)

- Sir Alwyne George Neville Ogden (1941, acting)

French consul-generals

- Louis Charles Nicolas Maximilien de Montigny (1863–1868)

- Henri Victor Fontanier (1869–1870)

- Charles Dillon (1870–1883)

- Ernest François Fournier (1883–1884)

- Paul Ristelhueber (1884–1891)

- Marie Jacques Achille Raffray (1891–1894)

- Jean Marie Guy Georges du Chaylard (1894–1897)

- Arnold Jacques Antoine Vissière (1897–1898)

- Jean Marie Guy Georges du Chaylard (1898–1902)

- Marie-Henri Leduc (1902–1903)

- Émile Rocher (1903–1906)

- Henri Séraphin Bourgeois (1906)

- Paul Claudel (1906–1909)

- Camille Gaston Kahn (1909–1912)

- Henri Séraphin Bourgeois (1913–1918)

- Jean Émile Saussine (1918–1923)

- Jacques Meyrier (1929–1931)

- Charles Jean Lépissier (1931–1935)

- Pierre Jean Crépin (1935–1937)

- Louis Charles (1937–1938)

- Charles Jean Lépissier (1938–1943)

- Georges Cattand (1943–1946)

German consul-generals

- Alfred Pelldram (1881–1885)

- Albert Evan Edwin Reinhold Freiherr von Seckendorff (1889–1896)

- Dr. Rudolf Eiswaldt (1896–1900)

- Arthur Zimmermann (1900–1902)

- Paul Max von Eckardt (1902–1905)

- Hubert von Knipping (1906–1913)

- Fritz Wendschuch (1913–1917)

Italian consul-generals

- Cesare Poma (1901–1903)

- Giuseppe Chiostri (1904–1906)

- Oreste Da Vella (1906–1911)

- Vincenzo Fileti (1912–1920)

- Marcello Roddolo (1920–1921)

- Luigi Gabrielli (1921–1924)

- Guido Segre (1925–1927)

- Luigi Neyrone (1927–1932)

- Filippo Zappi (1932–1938)

- Ferruccio Stefenelli (1938–1943)

Japanese consul-generals

- Minoji Arakawa (1895–1896)

- Tei Nagamasa (1896–1902)

- Hikokichi Ijuin (1902–1907)

- Kato Motoshiro (1907, acting)

- Obata Yukichi (1907–1913)

- Kubota Bunzo (1913–1914)

- Matsudaira Tsuneo (1914–1919)

- Ishii Itaro (1918, acting)

- Tatsuichiro Funatsu (1919–1921)

- Yagi Motohachi (1921–1922)

- Shigeru Yoshida (1922–1925)

- Hachiro Arita (1925–1927)

- Kato Sotomatsu (1927–1929)

- Okamoto Takezo (1929–1930)

- Tajiri Akiyoshi (1930–1931)

- Kuwashima Kazue (1931–1933)

- Kurihara Tadashi (1933–1934)

- Kawagoe Shigeru (1934–1936)

- Horiuchi Tateki (1936–1938)

- Tashiro Shigenori (1938–1939)

- Kato Shigeshi (1942–1943)

- Shinichi Takase (1943–1945)

Russian consul-generals

- Nikolai Vasilievich Laptev (1903–1907)

- Nikolai Maksimovich Poppe (1907–1909)

- Nikolai Sergeievich Muliukin (1909–1910, acting)

- Khristophor Petrovic Kristi (1910–1913)

- Konstantin Viktorovich Uspensky (1913–1914, acting)

- Pyotr Genrikhovich Tiedemann (1914–1920)

Galleries

British concession

The HSBC Building on Victoria Road, built in 1925

The HSBC Building on Victoria Road, built in 1925 The Yokohama Specie House on Victoria Road, built in 1926

The Yokohama Specie House on Victoria Road, built in 1926 The Russo-Asiatic House on Victoria Road, built in 1896

The Russo-Asiatic House on Victoria Road, built in 1896 Victoria Restaurant, built in 1940, now Kiessling Restaurant

Victoria Restaurant, built in 1940, now Kiessling Restaurant All Saints' Church, or Episcopal Church, built in 1936

All Saints' Church, or Episcopal Church, built in 1936 The Astor Hotel on Victoria Road, built in 1886, was one of the oldest structures in the British concession.

The Astor Hotel on Victoria Road, built in 1886, was one of the oldest structures in the British concession. The British Consul-General's Mansion, built in 1937

The British Consul-General's Mansion, built in 1937 The auditorium of Tienchin Kung Hsueh (now Yaohua High School) in the 1940s

The auditorium of Tienchin Kung Hsueh (now Yaohua High School) in the 1940s Tientsin Synagogue, built in 1940

Tientsin Synagogue, built in 1940 Prince Ching's Mansion in the Extra Rural Extension

Prince Ching's Mansion in the Extra Rural Extension

French concession

The Executive Office of the French Concession, built in 1929, is now a national, historical, and cultural site.

The Executive Office of the French Concession, built in 1929, is now a national, historical, and cultural site. The Municipal Council of the French Concession on Rue de France, built in 1934

The Municipal Council of the French Concession on Rue de France, built in 1934 The International Bridge, or Settlement Bridge, built in 1927, was a movable bridge and one of the historical landmarks in Tianjin.

The International Bridge, or Settlement Bridge, built in 1927, was a movable bridge and one of the historical landmarks in Tianjin.- The Banque de l'Indochine Building on Rue de France, built in 1912

The Gulf Building (or Po Hai Building), built in 1937, was the tallest building in Tientsin before the 1960s. Tianjin World Financial Center can be seen behind.

The Gulf Building (or Po Hai Building), built in 1937, was the tallest building in Tientsin before the 1960s. Tianjin World Financial Center can be seen behind. The National Commercial Bank, Tientsin branch building, built in 1921

The National Commercial Bank, Tientsin branch building, built in 1921 The Exhibition of Industrial Encouragement, built in 1928, was one of the largest department stores and historical landmarks in Tianjin.

The Exhibition of Industrial Encouragement, built in 1928, was one of the largest department stores and historical landmarks in Tianjin.- The Church of St. Louis, built in 1872, was one of the oldest structure in the French concession.

The Industrial and Commercial Bank of the Franco-Chinese building on Rue de France built in 1933

The Industrial and Commercial Bank of the Franco-Chinese building on Rue de France built in 1933 Li Chi-fu's Mansion near the French Garden, built in 1918, now serves as the seat of the Heping District government.

Li Chi-fu's Mansion near the French Garden, built in 1918, now serves as the seat of the Heping District government.

German concession

The German Club on Wilhelmstraße

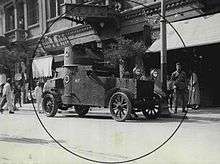

The German Club on Wilhelmstraße Barracks of the U.S. 15th Infantry Regiment

Barracks of the U.S. 15th Infantry Regiment The Pei-Ho Conservancy Commission, built in 1911

The Pei-Ho Conservancy Commission, built in 1911 The Tung Kuang Building on Wilhelmstraße

The Tung Kuang Building on Wilhelmstraße The Queue General's Mansion, built in 1899

The Queue General's Mansion, built in 1899

Italian concession

The Italian consulate, built in 1916

The Italian consulate, built in 1916 Italian Army barracks, built in 1916

Italian Army barracks, built in 1916 Current statue and houses on Piazza Regina Elena, which is now a national historical and cultural site

Current statue and houses on Piazza Regina Elena, which is now a national historical and cultural site North China Conservancy Commission

North China Conservancy Commission- Sacred Heart Church, built in 1922

Japanese concession

Butoku Hall, one of the latest structures in the Japanese concession

Butoku Hall, one of the latest structures in the Japanese concession.jpg) Tsao Ju-lin's house

Tsao Ju-lin's house Matsushima Girls' Business School

Matsushima Girls' Business School The Old Silk Company

The Old Silk Company Lu Chung-lin's house

Lu Chung-lin's house Zhang Villa, where former emperor Puyi lived from 1925 to 1927

Zhang Villa, where former emperor Puyi lived from 1925 to 1927 Jing Garden aka. Garden of Serenity (静园), where the former emperor Puyi lived from 1927 to 1931

Jing Garden aka. Garden of Serenity (静园), where the former emperor Puyi lived from 1927 to 1931

Notes

- The former German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian concessions, respectively renamed the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Special Districts, survived as distinct administrative entities administered by the Chinese government under a regime similar to that of the remaining foreign concessions.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 963.

- Magyar Királyi Központi Statisztikai Hivatal (1907) [Composed 1901]. "A magyar korona területén kivül tartózkodott magyar honos katonák a cs. és kir. közös hadügyminiszter által megküldött számlálólapok alapján, összeirási (tartózkodási) helyük szerint" [The number of Hungarian nationality soldiers dispatched abroad according to the re-enlisting papers emitted by the Royal and Imperial joint Minister of Military affairs sorted by their place of enlisting (dispatchment)]. A magyar szent korona országainak 1901. évi népszámlálása: Harmadik rész. A népesség részletes leirása [Census of 1901 in the countries of the Holy Crown: Volume III. The detailed description of the population.] (scan) (census). Magyar statisztikai közlemények (in Hungarian). 5 (new ed.). Budapest: Pesti Könyvnyomda-Részvénytársaság. p. 31. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- Géza Szuk (1904). "A mi Kis Khinánk" [Our Little China] (PDF). Vasárnapi Ujság. 18 (51): 292–294. Retrieved 2011-01-19.

- Jens Budischowsky (May 28, 2010). "Die Familie des Wirtschaftswissenschaftlers Joseph Alois Schumpeter im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert" [The family of economic scientists, Joseph Alois Schumpeter in the 19th and 20th century] (PDF). www.schumpeter.info (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- Anne-Marie Brady; Douglas Brown (2012). Foreigners and Foreign Institutions in Republican China. Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 9780415528658.

- Headquarter building of Italy in Tientsin Archived March 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Sabina Donati, Italy’s Informal Imperialism in Tianjin during the Liberal Epoch, 1902–1922, The Historical Journal, Cambridge University Press, 2016, available on CJO2016, doi:10.1017/S0018246X15000461.

- "Il Battaglione Italiano in Cina". Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- "Bristol University | Tianjin under Nine Flags, 1860-1949 | Russian Concession".

- Eileen Wilson (30 May 2011). "World War II vet recalls battle on two fronts". granitbaypt.com.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Concessions in Tianjin. |